Abstract

Objective

This study evaluates the thermographic changes associated with moxa burner moxibustion at the SP6 acupuncture point to establish an appropriate, safe distance of efficacy for moxibustion.

Methods

Baseline temperature changes using a moxa burner were obtained for a paper substrate at various distances and times, and the tested with volunteers in a pilot study. A single-group trial was then conducted with 36 healthy women to monitor temperature changes on the body surface at the acupuncture point (SP6).

Results

Based on the temperature changes seen for the paper substrate and in the pilot study, a distance of 3 cm was chosen as the intervention distance. Moxibustion significantly increased the SP6 point skin surface temperature, with a peak increase of 11°C at 4 min (p <0.001). This study also found that during moxibustion the temperature of the moxa burner's rubber layer and moxa cautery were 56.9±0.9°C and 65.8±1.2°C, as compared to baseline values of 35.1°C and 43.8°C (p<0.001).

Conclusions

We determined 3 cm was a safe distance between the moxa burner and acupuncture point. Moxibustion can increase the skin surface temperature at the SP6 point. This data will aid traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practitioners in gauging safer treatment distances when using moxibustion treatments.

Keywords: Acupuncture

Introduction

Moxibustion is an important component of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). It is a thermal treatment procedure that involves ignited material (usually moxa) near specific points for treating disease. Moxibustion is used to regulate meridians/channels and visceral organs of the human body.1 In traditional Chinese medicine, moxibustion treatment is considered effective for regulating the condition of cold-deficiency or qi movement stagnation, but is contraindicated in what is described as ‘excess’ disease and in fever due to Yin deficiency.2 Clinical trials and systematic reviews have evaluated the effect of moxibustion on such conditions as fetus breech presentation,3–5 dysmenorrhoea,6 ulcerative colitis,7 pain,8 constipation,9 acute lymphangitis,10 immunomodulation,11 cancer12 and stroke.13

The duration of treatment and the distance between the moxa burner and acupuncture point for moxibustion are crucial factors influencing moxibustion effectiveness. It has been suggested that the duration of moxibustion at each point should be 3–5 min, but not more than 10–15 min.2 3 5 11 In 2010, the National Standards of the People's Republic of China recommended covering the moxa burner with 8–10 layers of gauze while implementing moxibustion, and that the appropriate distance between the moxa burner and skin surface was 2–3 cm.14 The patient should feel comfortable, and not experience any burning sensations.

San yin jiao (SP6) is the intersection of the three Yin channels of the leg (the spleen, the liver and the kidney channels), which is traditionally considered especially useful as a ‘balancing’ point. It is located on the medial lower leg, about 7.6 cm (3 inches) above the prominence of the medial malleolus.15 It is the acupuncture point of choice in gynaecology and is readily accessible for moxibustion treatment.2

Hyperthermia is variously defined as a body core temperature higher than 37.5–38.3°C.16–18 When the environmental temperature is higher than the body, heat transmits into the body via conduction, convection, or radiation. The therapeutic effects of heat include (1) increased extensibility of collagen tissues and (2) vasodilatation and increased blood flow to the affected area. The increased rate of circulation acts to provide nutrients and oxygen to promote tissue healing.16 17 Moxibustion is also used to regulate blood flow and qi.2 19 Superficial hyperthermic temperature is skin temperature maintained at 40–45°C.16 17 20 A study by Adriaensen et al21 showed that thermal stimulation of human skin at 44.5–46.5°C activated A-fibre mechano-heat-sensitive nociceptors. Mori et al22 23 showed that the maximum temperature for indirect moxibustion was approximately 50°C.

Moxibustion carries health hazards, including the possibility of burns.24–26 Animal studies of the thermal properties of indirect moxibustion show that the maximum temperature induced by indirect moxibustion was about 65°C on the skin surface and 45°C in the subcutaneous layer.27 Excessive heating can cause protein denaturation and cell damage.16 17 In a study by Park et al,28 five participants (n=51) experienced burn injuries as a result of indirect moxibustion (an incident rate of 9.8%). Yamashita et al26 stated that therapist negligence was one of the main reasons for burn injuries. Changes in skin surface temperature (SST) as a result of moxibustion are of concern. In order to avoid burns and ensure the safety of clients, the medical staff must be aware of the clients’ sensitivity to temperature and pain. According to Cheng et al, ‘The operator by focusing his attention and whisking away the burning ash in a timely manner and giving advice on the intensity of stimulation was advising the participant not to let the points become uncomfortably hot’.29 The physical condition of the client before the decision to use heat in a therapeutic regimen must first be assessed in order to determine safe levels of heat. The patient must be able to perceive when the pain threshold has been reached.17 During thermal treatment, the medical staff must continuously observe the client's skin, blood pressure, heart rate and comfort level. If the client complains or any discomfort develops, treatment must be terminated.30

Moxa burner moxibustion uses a moxa burner to hold the ignited moxa floss,1 and is a common treatment in Chinese medicine. The current literature is sparse in research on SST changes at acupuncture points in relation to moxa burner moxibustion. This study aimed to investigate the changes in SST at the SP6 acupuncture point in order to develop a reference point for clinical use to improve patient safety.

Materials and methods

Materials

A moxa burner (figure 1A) made of Bakelite, 10 cm in height, with a 2.5 cm hole in the base and a 24.5 cm long handle, was used. The heat-resistant chamber is held firmly in place by three metal spring clamps. A laboratory stand and clamp were used to maintain the moxa burner at a fixed distance for the entire moxibustion process. The Bakelite moxa extinguisher and protective screen were included. The moxa rolls were 1.7 cm diameter, 20 cm long and weighed 30 g. The main ingredient of the moxa was dried mugwort leaf, produced in Taiwan. All moxa materials were obtained from the Kai Yip Acupuncture & Moxibustion Appliance Co, Taipei, Taiwan.

Figure 1.

(A) A schematic diagram illustrating the experimental set up. (B) Moxibustion via moxa burner at SP6 acupuncture point as seen by infrared camera. SP01: Moxa cautery instrument rubber surface; AR02: moxa cautery instrument lignin surface.

Setting and subjects

The study was conducted at the Laboratory of Nursing Research, Tzu Chi College of Technology. To account for the effects of circadian rhythms, measurements were taken from 08:30 to 18:00 The room was kept quiet and the ambient temperature and relative humidity were measured at approximately 21–26°C and approximately 60% to 80%. Participants wore comfortable clothes and sat on high-backed chairs with their foot elevated.

To achieve a power of 0.8 at α value=0.05, with a 0.5 of effect size, a typical correlation (r=0.50) and using a repeated measures analysis of covariance for acupuncture point temperature, the required size for each group was estimated to be 35 participants.31 Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Mennonite Christian Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB: 09-09-037-ER).

Study design and procedure

Two topics were examined: the appropriate distance for moxibustion, and changes of SST at SP6. First, to find out the appropriate distance for moxibustion, the surface temperature of A4 paper was used to determine when therapeutic temperatures had been reached (40°C). Temperature changes were recorded at 10 min intervals for distances of 1 –7 cm from the moxa burner (figure 1A). To confirm 3 cm as the appropriate distance for the moxa burner and SP6 acupuncture point on a human being, we conducted a pilot study. Volunteers were used to test the most suitable distance according to subjective reports and SSTs, comparing distances of 4 cm, 3 cm and 2 cm. Secondly, to measure the changes of SST at SP6, a single-group trial was conducted to monitor body surface temperature changes at acupuncture point SP6 by moxibustion.

Participants provided informed consent and were assigned to repeated measurements on a same day basis. Participant SSTs were recorded twice, with a 4 h washout period between each measurement. The resting period and moxibustion period were both 40 min. Moxibustion was maintained for 10 min on the acupuncture point (SP6) at a distance of 3 cm. Subjects remained seated for 10 min in order to become acclimatised to the room temperature; the baseline SST was then recorded. After completion of 10 min of moxibustion, the moxa burner was removed and the subjects remained resting in a seated position for another 10 min. The SST was recorded during and after moxibustion at 2-min intervals.

Measures

Participant characteristics

The study included 36 women, all volunteers, without fever, pregnancy, musculoskeletal disorders, prior surgery or pain symptoms in the lower limbs. Volunteers with any disease capable of altering body temperature or taking drugs that could affect autonomic nervous system function were screened out. Participants with medical conditions that were considered under control (eg, hypertension, asthma, diabetes) were included. All were instructed not to eat 2 h prior to the experiment. Participants were requested not to ingest any chemical stimulants (eg, coffee, tea, medications etc.) during the entire moxibustion period.

Measurements of paper, skin surface and moxa burner temperatures

There were two components in this process: the first part aimed to determine the appropriate distance for using moxibusion. The second part aimed to measure the SST of SP6 and moxa burner (SP01=rubber layer, AR02=moxa cautery instrument lignin surface) temperature during moxibustion.

An infrared camera (FLIR ThermaCAM P25 HS system) was used to measure surface temperatures for A4 paper at different distances and the skin of the acupuncture point (SP6) at different times during moxibustion. The FLIR infrared camera is a hot element detector, with 320×240 pixel geometric resolution of 76.800 pixel per picture that can be achieved and the range of the thermometer is 0−250°C±0.01°C. The data were transferred to a notebook computer using the ThermaCAM Researcher V.2.8 software and analysed with the same (FLIR Systems Inc., Portland, Oregon, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS V.17.0 for Windows, (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) and expressed as mean±SEM. Non-parametric tests were used to evaluate differences between the groups and times. Wilcoxon signed rank and Friedman tests were used to compare treatment effects on groups at different times. The level of significance was set at a p value of 0.05.

Results

Participant details

The participants’ ages ranged from 21 to 60 years, with mean±SD age of 32.4±8.5 years. The majority were non-smokers (n=36, 100%), non-hypertensive (n=36, 100%), non-asthmatic (n=33, 96%) and non-diabetic (n=36, 100%). No volunteers were currently using or had been prescribed any drugs that could affect the autonomic nervous system function. All 36 subjects were Taiwanese, without fever, musculoskeletal disorders, prior surgery or pain symptoms in the lower limbs. There were no adverse events recorded during the study.

Appropriate distance for moxibustion

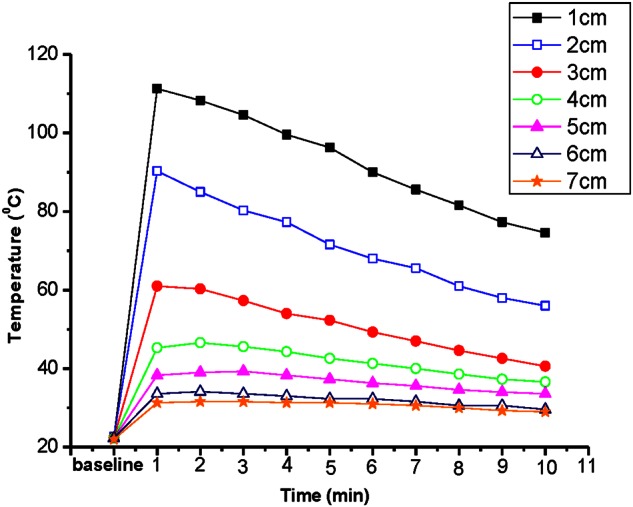

Baseline temperatures showed no significant differences prior to ignition of the moxa burner at different distances from 1–7 cm away from the A4 paper. The temperature rapidly increased to 111.3±4.9°C and 90.3±10.7°C for distances of 1 and 2 cm in the first minute, thereafter temperatures decreased to 74.6±2°C and 56±2.6°C by the 10th minute, and remained significantly higher than baseline during the moxibustion period.

At distances of 5, 6 and 7 cm, the temperatures were 38.3±0.5°C, 33.6±1.5°C and 31.3±2°C at the first minute, decreasing to 33.6±0.5°C, 29.6±0.5°C and 29±2°C at the 10th minute. Although temperature remained significantly higher than baseline during the moxibustion period, at all distances the temperature remained lower than 40°C. In the 4 cm distance group, the temperature reached 45.3±1.1°C in the first minute then decreased to 38.6±2°C at the eighth minute and fell to to 36.6±0.5°C at the 10th minute. The temperature in the 3 cm distance group was between 61.0–40.6°C (first minute=61.0±3.6°C, 10th minute=40.6±2°C), higher than the baseline of 38.6–18.2°C. According to the results, 3 cm remains an appropriate distance between the moxa burner and SP6 acupuncture point (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Changes in temperature on paper by moxibustion at different distances.

The subjects in the pilot study did not report a sensation of heat at 4 cm. At 2 cm a burning sensation was reported. At 3 cm, subjects reported a comfortable feeling with hyperthermia (first minute=36.5°C, 10th minute=41°C).

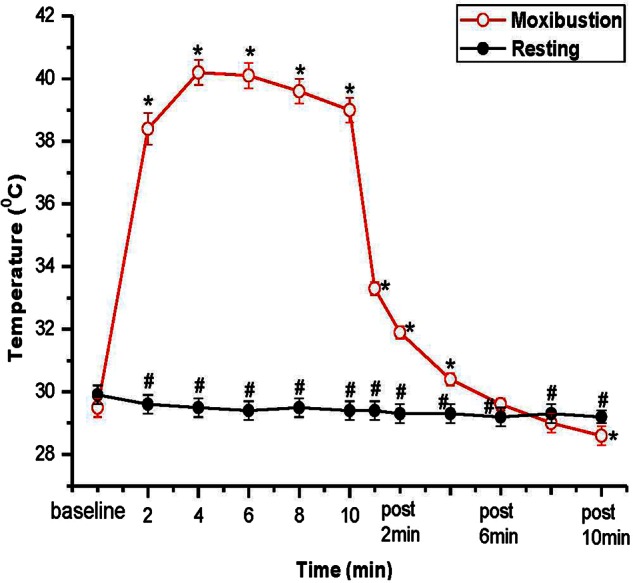

Changes of SST at SP6

The average temperatures at the SP6 acupuncture point showed no significant differences between groups before moxibustion. The SST of the SP6 point gradually increased to a peak of 40.2±0.4°C at the fourth minute after moxibustion, significantly higher than baseline (29.2±0.3°C) (p<0.001) (figure 3). Furthermore, after completion of moxibustion, the SST remained 1.2°C higher than the baseline at 4 min (figure 3). The Friedman tests revealed that, from baseline to the 10th minute and to the 10th minute post cessation of treatment, moxibustion can increase the SST of SP6 (p<0.001) (table 1). During the resting period, the SP6 temperature gradually decreased to a level of 29.2±0.3°C at the fourth minute after moxibustion, significantly lower than baseline (29.9±0.3°C) (p<0.01) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Changes of temperature by moxibustion at different times (distance=3 cm). *p<0.01 indicates the moxibustion group's skin at SP6 at different time points compared with baseline by Wilcoxon signed rank test; #p<0.01 indicates the rest group's skin at different time points compared with baseline by Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Table 1.

Treatment effects at different time points (from baseline to 10th minute and p 10th minute)

| Measurement indices | From baseline to 10th minute | From baseline to p 10th minute | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p Value | χ2 | p Value | |

| Moxibustion (n=36) | ||||

| SP6T | 122.020 | <0.001*** | 139.943 | <0.001*** |

| Resting (n=36) | ||||

| SP6T | 14.596 | 0.012 | 14.347 | 0.014 |

Data show overall time point differences by Friedman test.

**p<0.01; ***p<0.001

10th minute, the 10th minute of moxibustion; p 10th minute, the 10th minute of rest after moxibustion; SP6T, SP6 acupuncture point temperature (°C).

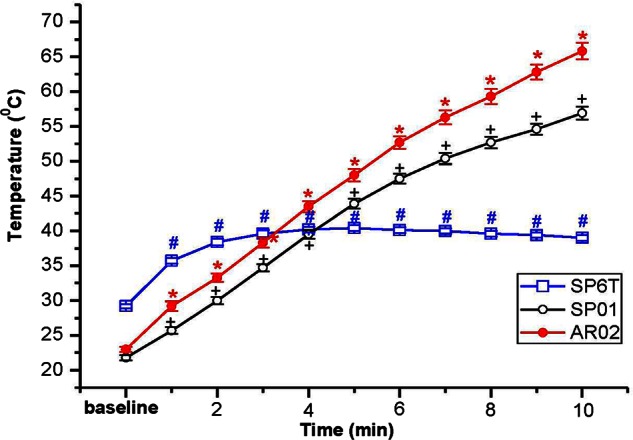

Changes in temperature of the moxa burner

The rubber layer of the moxa burner can easily come into contact with a patient's skin if the practitioner is not cautious. According to our findings in the first part of our investigation, the rubber layer of the moxa burner can reach temperatures of 65°C and higher. Therefore recording the changes of temperature caused by moxibustion at different times on the moxa cautery instrument rubber surface (SP01) and moxa cautery instrument lignin surface (AR02) was undertaken (figure 1B). The temperature changes of the moxa burners were recorded over time. At SP01, the temperatures were 21.8±0.4°C at the baseline, increasing to 56.9±0.9°C after 10 min with moxibustion—a change of 35.1°C (p<0.001). At AR02, the temperatures were 23.0±0.4°C at the baseline, increasing to 65.8±1.2°C after 10 min with moxibustion—a change of 43.8°C (p<0.001). The surface temperature of the moxa burner was higher than the skin at SP6 after the fourth minute of moxibustion (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Changes of temperature by moxibustion at different times on moxa burner. #p<0.01 indicates SP6 at different time points compared with baseline by Wilcoxon signed rank test; +p<0.01 indicates SP01 (moxa cautery instrument rubber surface) at different time points compared with baseline by Wilcoxon signed rank test; *p<0.01 indicates AR02 (moxa cautery instrument wooden/plastic section) at different time points compared with baseline by Wilcoxon signed rank test. SP6T: SP6 acupuncture point temperature; SP01: moxa cautery instrument rubber surface; AR02: Moxa cautery instrument lignin surface.

Discussion

An appropriate distance for administering moxibustion

The National Standards of the People's Republic of China14 recommends 2–3 cm as a safe distance for the administration of moxibustion treatment. The results of this study support the 3 cm safe distance recommendation.

The results showed that SST at SP6 was maintained at 38.4–40.2°C during the moxibustion period. This achieved the effect of hyperthermic temperature (37.5–38.3°C),16–18 while remaining lower than the mild burn temperature (60°C).32 33 Some studies have mentioned that superficial hyperthermia temperature is maintained at 40–45°C.16 17 20 However, individuals have different pain thresholds. In the pilot test, two volunteers reported pain at a distance of 2 cm during treatment. It is necessary to pay attention to the clients’ experience during moxibustion treatment.30 We think 3 cm is an appropriate distance between the moxa burner and acupuncture point.

Safety concerns with moxibustion

Prior studies stated that the mild burn temperature was 60°C.32 33 This study found that the temperature of the moxa burner rubber layer (SP01) and moxa cautery (AR02) reached 56.9±0.9–65.8±1.2°C during moxibustion. Prevention of burns during moxibustion is of great concern as well as burns due to falling ash from the moxibustion process.24 25 There were no adverse events in this study, possibly due to using a fixed holder with the moxa burner. In clinical situations, it is common to hold the moxa burner by hand rather then use a fixed holder. By maintaining the foot in an elevated position, ash could fall directly to the ground instead of onto the subjects’ skin (figure 1B). It is necessary to set more precise guidelines to prevent burning during moxibustion in clinical use.

Study limitations

This research was implemented using healthy women in eastern Taiwan, therefore the research findings may not be suitable for extrapolation to the entire population. In addition, the research was only implemented on the SP6 point. The effect on different acupuncture points on the body warrants further exploration.

Conclusions

Based on these results, we consider 3 cm between the moxa burner and acupuncture point is an appropriate distance for administering moxibustion. However, further research is required to support our findings. An effective hyperthermia temperature of 37.5–38.3°C was obtained at the second minute after moxibustion, and was maintained until the 10th minute. The peak was in he fourth minute (40.2±0.4°C) after moxibustion. The SST of SP6 increased to a peak and was significantly higher than the resting group. Moreover, the temperature of the moxa burner rubber layer (SP01) and moxa cautery (AR02) reached 56.9±0.9–65.8±1.2°C during moxibustion. It is necessary to take great care with moxa cautery instrument rubber surfaces to prevent burns during moxibustion.

These findings provide a clinical practical reference point, with scientific evidence that burn prevention during moxibustion is readily preventable.

Summary points.

Moxa has to be used close enough to heat tissues (>37−40°C) without burning (>60°).

A preliminary study suggested a distance of 3cm.

At 3cm, skin temperature of volunteers reached the required temperature.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Tzu Chi College of Technology and research grants provided by Chang Gung Institute of Technology. This work was supported by Chang Gung Institute of Technology, grant number EZRPF380071.

Footnotes

Contributors: LML: conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, final approval. RPL: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript, final approval. SFW: interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript, final approval. BGH: interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript. NMT: interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript. TCP: conception, design, interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript, final approval.

Funding: The Chang Gung Institute of Technology funded this work (EZRPF380071).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was granted by the Mennonite Christian Hospital institutional review board (IRB: 09-09-037-ER).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Open Access: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/

References

- 1.World Health Organization Western Pacific Region WHO international standard terminologies on traditional medicine in the western pacific region. http://www.wpro.who.int/NR/rdonlyres/14B298C6-518D-4C00-BE02-FC31EADE3791/0/WHOIST_26JUNE_FINAL.pdf (accessed 21 Oct 2010).

- 2.Liu G, Liya C. Clinical acupuncture and moxibustion. Tiznjin, China: Tiznjin, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B. Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;18:CD003928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li X, Hu J, Wang X, et al. Moxibustion and other acupuncture point stimulation methods to treat breech presentation: a systematic review of clinical trials. Chin Med 2009;4:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vas J, Aranda JM, Nishishinya B, et al. Correction of non-vertex presentation with moxibustion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:241–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun LH, Yang JJ, She YF, et al. Randomized controlled clinical study on ginger-partitioned moxibustion for patients with cold-damp stagnation type primary dysmenorrhea. Zhen ci yan jiu 2009;34:398–402 (Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee DH, Kim JI, Lee MS, et al. Moxibustion for ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 2010;10:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee MS, Choi TY, Kang JW, et al. Moxibustion for treating pain: a systematic review. Am J Chin Med 2010;38:829–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee MS, Choi TY, Park JE, et al. Effects of moxibustion for constipation: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Chin Med 2010;5:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou W. Acute lymphangitis treated by moxibustion with garlic in 118 cases. J Tradit Chin Med 2003;23:198 (Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kung YY, Chen FP, Hwang SJ. The different immunomodulation of indirect moxibustion on normal subjects and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Chin Med 2006;34:47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee MS, Choi TY, Park JE, et al. Moxibustion for cancer care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2010;10:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee MS, Shin BC, Kim JI, et al. Moxibustion for stroke rehabilitation: systematic review. Stroke 2010;41:817–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Standardization Administration of the People's Republic of China National standards of the People's Republic of China (GB/ T 21709. 1–2008): Standardized manipulations of acupuncture and moxibustion-Part 1: moxibustion. Chin Acupunct & Moxibust 2010;30:501–4 (China). [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization WHO standard Acupuncture Point Location in the Western Pacific Region. http://www.wpro.who.int/NR/rdonlyres/2CA01D1F-DA5B-49C1-881C-89EB3D0AD920/0/part3_WHO Standard Accupuncture Point Locations.pdf (accessed 21 Oct 2010).

- 16.Hecox B, Mohrotoab TA, Weisberg J. Physical agents: a comprehensive text for physical therapists. East Norwalk, CT: Appleton Lange Inc., 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cameron MH. Physical agents in rehabilitation: from research to practice. 3rd edn St. Louis, MO: Saunders, Elsevier Inc., 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schepers RJ, Ringkamp M. Thermoreceptors and thermosensitive afferents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2009;33:205–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gongwang L. Clinical Acupuncture & Moxibustion. Tianjin, China: Nankai, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadler SF, Weingand K, Kruse RJ. The physiologic basis and clinical applications of cryotherapy and thermotherapy for the pain practitioner. Pain Physician 2004;7:395–99 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adriaensen H, Gybels J, Handwerker HO, et al. Response properties of thin myelinated (A-delta) fibers in human skin nerves. J Neurophysiol 1983;49:111–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mori H, Tanaka TH, Kuge H, et al. Is there a difference between the effects of one-point and three-point indirect moxibustion stimulation on skin temperature changes of the posterior trunk surface? Acupunct Med 2012;30:27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mori H, Kuge H, Tanaka TH, et al. Is there a difference between the effects of single and triple indirect moxibustion stimulations on skin temperature changes of the posterior trunk surface? Acupunct Med 2011;29:116–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park JE, Lee SS, Lee MS, et al. Adverse events of Moxibustion: a systematic review. Complement Ther Med 2010;18:215–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wheeler J, Coppock B, Chen C. Does the burning of moxa (Artemisia vulgaris) in traditional Chinese medicine constitute a health hazard?. Acupunct Med 2009;27:16–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamashita H, Tsukayama H, Tanno Y, et al. Adverse events in acupuncture and moxibustion treatment: a six-year survey at a national clinic in Japan. J Altern Complement Med 1999;5:229–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiba A, Nakanishi H, Chichibu S. Effect of indirect moxibustion on mouse skin. Am J Chin Med 1997;25:143–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park J-E, Lee MS, Jung S, et al. Moxibustion for treating menopausal hot flashes: a randomized clinical trial. Menopause 2009;16:660–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng CW, Fu SF, Zhou QH, et al. Extending the CONSORT statement to moxibustion. J Integr Med 2013;11:54–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elkin MK, Perry AG, Potter PA. Therapeutic use of heat and cold. In: Nursing interventions & clinical skills. St. Louis, Canada: Mosby Elsevier, 2007:541–8 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steven AJ. Generalised Wilcoxon test. In: Steven AJ, ed. Sample sizes for clinical trials. San Diego, CA: CRC Press INC, 2010:248–61 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng EYK, Chua LT. Comparison of one- and two-dimensional programmes for predicting the state of skin burns. Burns 2002;28:27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang SC, Ma N, Li HJ, et al. Effects of thermal properties and geometrical dimensions on skin burn injuries. Burns 2002;28:713–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]