Abstract

Oligomerization reaction of the E. coli DnaT protein has been quantitatively examined using the fluorescence anisotropy and analytical ultracentrifugation methods. In solution, DnaT exists as a monomer - trimer equilibrium system. At the estimated concentration in the E. coli cell, DnaT forms a mixture of the monomer and trimer states with 3:1 molar ratio. In spite of the modest affinity, the trimerization is a highly cooperative process, without the detectable presence of the intervening dimer. The DnaT monomer is built of a large N-terminal core domain and a small C-terminal region. The removal of the C-terminal region dramatically affects the oligomerization process. The isolated N-terminal domain forms a dimer instead of the trimer. These results indicate that the DnaT monomer possesses two structurally different, interacting sites. One site is located on the N-terminal domain and two monomers, in the trimer, are associated through their binding sites located on that domain. The C-terminal region forms the other interacting site. The third monomer is engaged through the C-terminal regions. Surprisingly, the high affinity of the N-terminal domain dimer indicates that the DnaT monomer undergoes a conformational transition upon oligomerization, involving the C-terminal region. These data and the high specificity of the trimerization reaction, i.e., lack of any oligomers higher than the trimer, indicate that each monomer in the trimer is in contact with the remaining two monomers. A model of the global structure of the DnaT trimer based on the thermodynamic and hydrodynamic data is discussed.

Keywords: DnaT Protein, Oligomerization, Fluorescence Anisotropy, Fluorescence Titrations, Protein - Protein Interactions, Primosome

The primosome is a multiple-protein-DNA complex, which catalyzes priming of the DNA strand during the replication process (1–15). The complex translocates along the DNA, a movement fueled by NTP hydrolysis, while synthesizing short oligoribonucleotide primers, which are used to initiate synthesis of the complementary DNA strand. Formation of the primosome was initially described at a specific primosome assembly site (PAS) in the replication of phage ϕX174 DNA (1,7,9,12). Present data show that the assembly of the primosome is a fundamental step in the restart of the stalled replication fork at the damaged DNA sites, i.e., the primosome is a molecular machine at the crossroads of replication and repair processes (4,7–9,12).

The DnaT protein is an essential replication protein in Escherichia coli that plays a primary role in the assembly of the primosome (1–8). The assembly process is initiated by recognition of the PAS sequence or the damaged DNA site by the PriA protein, or the PriB protein - PriA complex, followed by the association of the DnaT and the PriC protein (1–9,13). The formed protein - DNA entity constitutes a scaffold, specifically recognized by the DnaB helicase - DnaC protein complex, which results in formation of the pre-primosome. Next, the pre-primosome is recognized by the primase and a functional primosome is formed. The DnaT protein is absolutely necessary for the specific entry of the DnaB helicase into the primosome complex. The protein was originally discovered as an essential factor during synthesis of the complementary DNA strand of phage ϕX174 DNA (1,13–15). The gene encoding the DnaT protein has been cloned and its sequence determined (15). The DnaT monomer contains 179 amino acids with a molecular weight of ~19.5 (15).

In spite of the fact that the specific role of the DnaT protein, as a key factor in the recruitment of the replicative helicase, DnaB protein, to the primosome has been recognized, little is known about the functional structure of the protein (14). The native DnaT has been proposed to be a homo-trimer, although biochemical data indicated the presence of monomer, dimer, tetramer, and pentamer (14). Studies of the pre-primosome and primosome components suggest that the functional form of the DnaT in the assembly might not be a trimer, but a monomer, or that the oligomerization/disassembly of the DnaT protein oligomer(s) could be specific parts of the primosome assembly process (3). Thus, such fundamental quantities as the number of monomers in the native and functional form of the DnaT protein, both in solution and in the primosome, are still under debate. Surprisingly, the nature of the association process of the DnaT monomers has never been experimentally established and the intrinsic energetics of the DnaT oligomerization reaction(s) are unknown.

In this communication, we report the quantitative analyses of the DnaT oligomerization process and the global structure of the specific DnaT oligomer. We establish that, in solution, the DnaT protein exists as a monomer-trimer equilibrium system. The oligomerization reaction is a highly specific and cooperative process. The DnaT monomer is built of the core N-terminal domain and the small flexible C-terminal region. The monomer possesses two structurally different binding sites located on the N-terminal core domain and the C-terminal region, respectively. The third monomer in the trimer binds to the remaining two monomers through the C-terminal regions. In the trimer, each monomer is in contact with the remaining two monomers.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Reagents and Buffers

All solutions were made with distilled and deionized >18 MΩ (Milli-Q Plus) water. All chemicals were reagent grade. Buffer C is 10 mM sodium cacodylate adjusted to pH 7.0 with HCl, 1 mM DTT, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 25% glycerol (w/v) (16–21).

The Wild-Type DnaT Protein and the Protein Variants

The wild-type E. coli DnaT protein gene has been placed under the T7 promoter in plasmid Pet30a. The constructs were obtained for the DnaT gene containing the C-terminal his-tag, as well as the protein variant, S3C, with serine residue 3 replaced by cysteine and containing the C-terminal his-tag (see below). All oligomerization experiments were performed with the wild-type protein without the his-tag. The constructs containing the his-tag were used in the separation of the N-terminal core domain of the protein from its C-terminal region (see below). The wild-type protein was over-expressed in Rosetta™ (DE3) cells (Novagen). Briefly, the DNA was removed from the cell extract by Polymin P (Sigma, MI) precipitation. The extract was passed through the Heparin Sepharose™ CL-6B (GE Healthcare) column at 300 mM NaCl (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.6, 10% (w/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT), followed by elution through the DEAE Sepharose CL-6B column at 150 mM NaCl (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.6, 10% (w/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT). The protein variants containing the his-tag have been purified using the metal-affinity Talon column (Clontech, CA). All purified proteins were > 99% pure as judged by polyacrylamide electrophoresis with Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. The protein concentrations were spectrophotometrically determined, with the extinction coefficient ε280 = 2.7960 × 104 cm−1 M−1 (monomer) obtained using an approach based on Edelhoch’s method (16–21,22,23).

Labeling of the DnaT Variant S3C with Fluorescein

The DnaT protein variant, S3C, was specifically labeled with fluorescein maleimide and purified according to the protocol previously described by us (24–26).

Trypsin Digestion Experiments

Time-dependent digestion of the DnaT protein with trypsin (Sigma, MI) has been performed in the same buffer C as the oligomerization experiments (16,27,28). The protein was mixed with the protease at the molar ratio, 37:1 (DnaT monomer: protease) and the reaction was stopped by adding the protease inhibitor, PMSF, heating at ~100°C for 5 minutes and adding a buffer containing 10% SDS. Several different DnaT protein - protease molar ratios were examined to obtain the optimal time dependence of the digestion reaction (16,27,28). The digestion reactions performed with the wild-type protein and the DnaT variants, discussed in this work, were indistinguishable.

Isolation of the N-Terminal Core Domain of the DnaT Protein

The N-terminal core domain of the DnaT protein was isolated using the DnaT variant containing the C-terminal his-tag (see above). The reaction mixture of the DnaT protein and trypsin was applied on the metal-affinity, Talon column (Clontech, CA). The N-terminal core domain does not stay on the column and was eluted using 10 mM sodium cacodylate pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 1 mM PMSF, and 10% glycerol. Subsequently, the C-terminal unstructured region of the protein was eluted with the same buffer containing 200 mM imidazole. The core domain was characterized by N-terminal amino acid sequencing and mass spectrometry. The concentration of the domain has been spectrophotometrically determined, using the extinction coefficient, ε280 = 2.7690 × 104 cm−1 M−1 (monomer) (16,21,22,23).

Fluorescence Measurements

All steady-state fluorescence titrations were performed using the ISS PC-1 spectrofluorometer (Urbana, IL), as previously described by us (29–34). The state of the DnaT protein oligomerization has been analyzed using the fluorescence anisotropy, r, of the protein tryptophan residues defined as (35–39)

| (1) |

where IVV and IVH are fluorescence intensities with the first and second subscripts refer to vertical (V) polarization of the excitation and vertical (V) or horizontal (H) polarization of the emitted light (35–40). The factor, G = IHV/IHH, corrects for the different sensitivity of the emission monochromator for vertically and horizontally polarized light (35–39). The sample was excited at 296 nm (protein tryptophan absorption band) and the emission recorded at 347 nm (protein tryptophan emission band).

Analytical Ultracentrifugation Measurements

Analytical ultracentrifugation experiments were performed with an Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman Inc., Palo Alto, CA), using double-sector charcoal-filled 12 mm centerpieces, as previously described by us (40–43). Sedimentation equilibrium scans were collected at the absorption band of the protein (280 nm), or at 497 nm for the DnaT S3C variant labeled with fluorescein. The sedimentation was considered to be at equilibrium when consecutive scans, separated by time intervals of 8 hrs, did not indicate any changes. For the n-component system, the total concentration at radial position r, cr, is defined by (44)

| (2) |

where cbi, ν̄i, and Mi are the concentrations at the bottom of the cell, partial specific volume and molecular weight of "i" component, respectively, ρ is the density of the solution, ω is the angular velocity, and b is the base-line error term. The partial specific volumes of the DnaT protein and its N-terminal core domain, calculated from the amino acid sequences, are ν̄i = 0.740 ml/g and ν̄i = 0.743 ml/g, respectively (45). Equilibrium sedimentation profiles were fitted to eq. 2 with Mi and b as fitting parameters (40–43).

Sedimentation velocity scans were collected at the absorption band of the DnaT protein at 280 nm. Time derivative analyses of sedimentation scans were performed with the software supplied by the manufacturer, using averages of eight to fifteen scans for each concentration as described before (40–43). The values of sedimentation coefficients, s20,w, were corrected to for solvent viscosity and temperature to standard conditions (44).

RESULTS

Oligomerization of the Wild-Type DnaT Protein in Solution

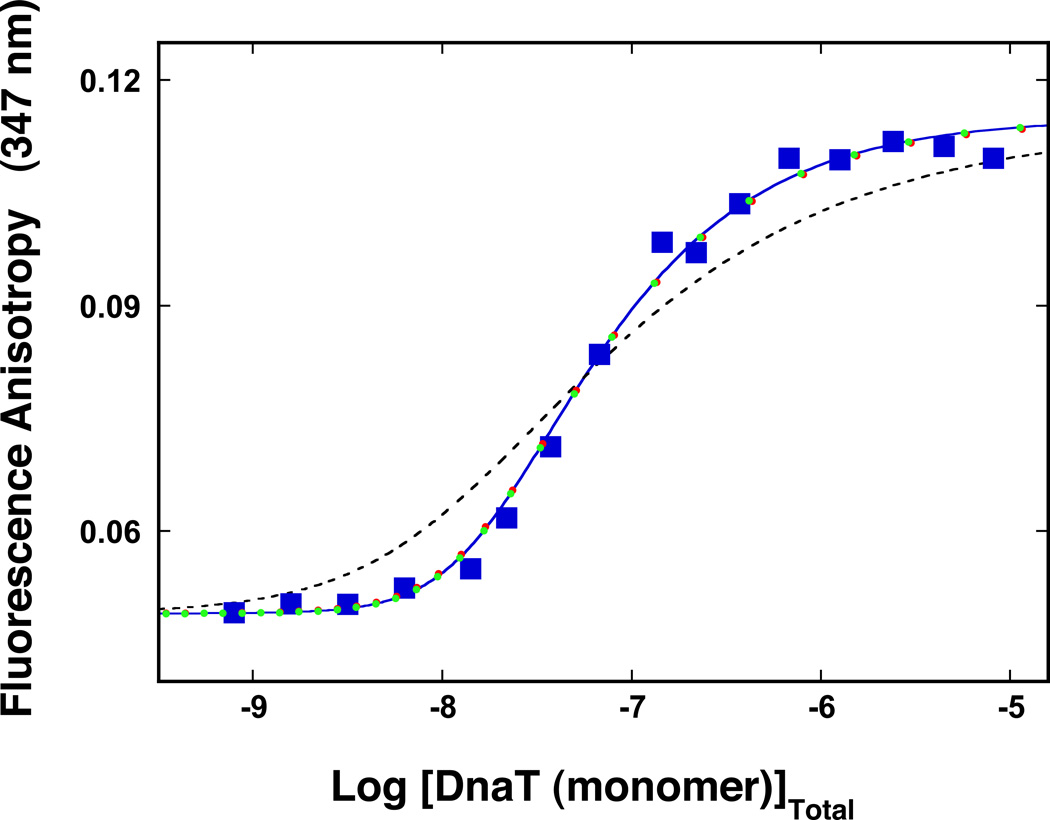

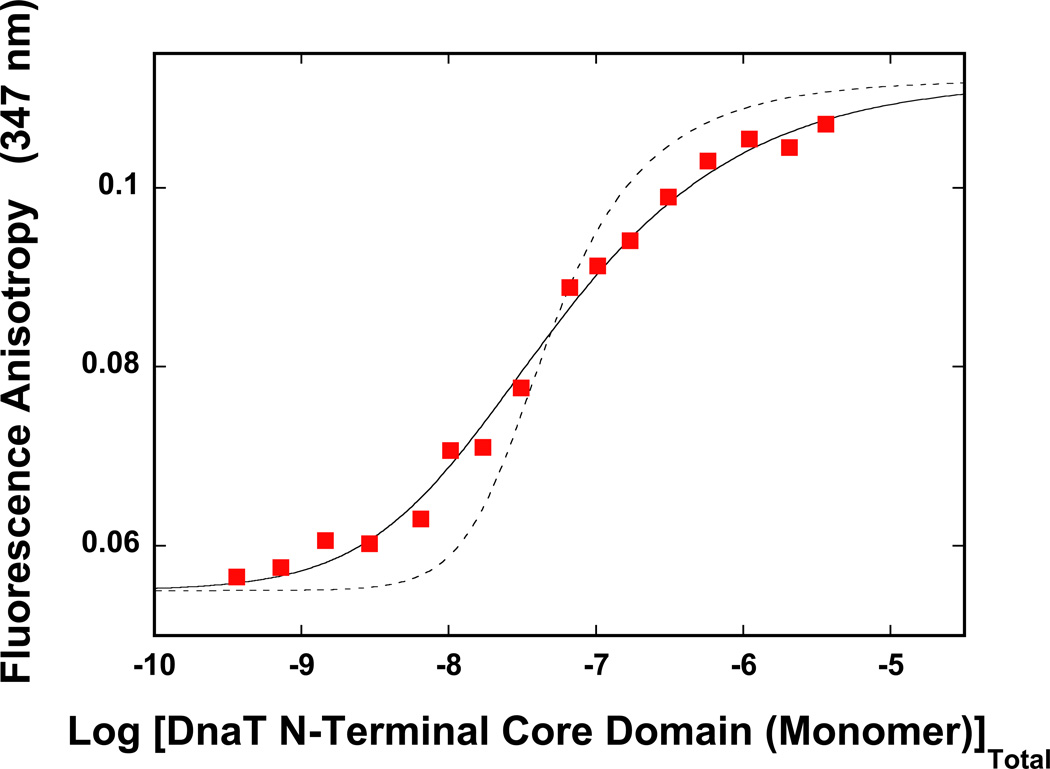

As mentioned above, early studies of the DnaT protein indicated that the protein forms different oligomeric states, although the trimer dominates the oligomer population (14). Because, the intensity of the fluorescence emission of the DnaT protein is strictly proportional to the protein concentration, i.e., it is not affected by the monomer association reactions (data not shown), the oligomeric state of the protein in solution has been addressed, using the steady-state fluorescence anisotropy method (35–40,46). The approach is very sensitive to the presence of the molecular species, differing in rotational correlation times, which is an expected outcome for the oligomerization reaction (35–40,46). The dependence of the DnaT protein fluorescence anisotropy upon the total monomer concentration, in buffer C (pH 7.0, 20°C), is shown in Figure 1. At the monomer concentrations lower than ~1 – 2 × 10−8 M the fluorescence anisotropy has a value of ~0.05. The increase of the monomer concentration causes the increase of the anisotropy of the sample, which, at saturation, reaches a plateau at r ≈ 0.115. These data indicate the presence of molecular species differing in fluorescence rotational correlation times, i.e., differing in their molecular masses (35–40,46). Moreover, the data show that the protein undergoes an association reaction, from the entity dominating at low [DnaT], i.e., monomer, to a specific species, which dominates the oligomer population at high protein concentrations (Figure 1). Nevertheless, at the total monomer concentration above ~10−5 M, the protein shows some tendency to aggregate (data not shown).

Figure 1.

The dependence of the DnaT fluorescence anisotropy upon the total DnaT monomer concentration (λex = 296 nm, λem = 347 nm) in buffer C (pH 7.0, 20°C) (Materials and Methods). The solid blue line is the nonlinear least-squares fit of the titration curve, using the trimer model described by eqs. 3 – 7 with KT = 3.5 × 1014 M−2, rM = 0.049, and rT = 0.115. The dashed line is the best fit of the titration curve using the monomer<-> dimer <-> trimer model described by eqs. 8 – 13, with KM = 1.8 × 107 M−1, rM = 0.049, rD = 0.082, and rT = 0.115. The symbols ( ) represent the nonlinear least squares fit of the titration curve using the cooperative monomer<-> dimer <-> trimer model (eq. 21a), with KM = 7 × 105 M−1, σ = 730, rM = 0.049, rD = 0.082, and rT = 0.115. The symbols (

) represent the nonlinear least squares fit of the titration curve using the cooperative monomer<-> dimer <-> trimer model (eq. 21a), with KM = 7 × 105 M−1, σ = 730, rM = 0.049, rD = 0.082, and rT = 0.115. The symbols ( ) represent the computer simulation of the titration curve, using the cooperative monomer<-> dimer <-> trimer model (eq. 21a), with KM = 1 × 105 M−1, σ = 35,000, rM = 0.049, rD = 0.082, and rT = 0.115.

) represent the computer simulation of the titration curve, using the cooperative monomer<-> dimer <-> trimer model (eq. 21a), with KM = 1 × 105 M−1, σ = 35,000, rM = 0.049, rD = 0.082, and rT = 0.115.

Inspection of the data in Figure 1 shows that the entire association curve spans less than ~2 orders of magnitude on the total concentration scale of the protein monomer, between 10% and 90% of the observed anisotropy change (35). Knowing that the final oligomeric state of the DnaT protein in the high [DnaT] range is a trimer (see below), such behavior provides the first indication that the observed association predominantly includes a monomer - trimer reaction (35). For instance, in the case of the dimerization reaction, the titration curve spans ~2.9 orders of magnitude on the total monomer concentration scale (see below) (35). Therefore, the association reaction is defined by the equilibrium process, in which three DnaT monomers form a trimer, as (47–56)

| (3) |

The equilibrium trimerization constant, KT, is

| (4) |

The total concentration of the DnaT monomer, [M]T, is defined in terms of the free monomer concentration, [M]F and KT, by the mass conservation expression as

| (5) |

The observed fluorescence anisotropy of the system is then defined by expression (35)

| (6) |

where rM and rT are fluorescence anisotropies of the monomer and the trimer, respectively. The quantities, fM and fT, are the fractional contributions of the monomer and the trimer to the total emission of the sample, and in general, are described as

| (7a) |

and

| (7b) |

where, FM and FTr are molar fluorescence intensities of the monomer and the trimer, respectively. Because the protein emission intensity is strictly proportional to the total monomer concentration (see above), one has FTr = 3FM in eqs. 7a and 7b. The solid line in Figure 1 is the nonlinear least-squares fit of the experimental titration curve, using eqs. 3 – 7. Both, rM and rT, can be estimated from the plateaus of titration curve. We have also additionally measured these parameters using the solutions of the DnaT protein with very low (~1 × 10−9 M (monomer)) and very high (~2 × 10−5 M (monomer)) protein concentrations, respectively. This leaves KT as an independent parameter. The fit provides, KT = (3.5 ± 0.6) × 1014 M−2, with rM = 0.049 ± 0.001, and rT = 0.115 ± 0.001. It is evident that the model provides an excellent description of the experimental titration curve.

For comparison, we also addressed the thermodynamic model, which includes the dimer as an intermediate but contains a single binding parameter similar to the trimer model discussed above, i.e., a single binding constant, KM, characterizing the monomer-monomer interactions. The equilibrium system is defined as (35,47–56)

| (8) |

The corresponding association constants are

| (9) |

and

| (10) |

The mass conservation of the total monomer concentration, [M]T, is then defined in terms of the free monomer concentration, [M]F, and KM as

| (11) |

The observed fluorescence anisotropy is described as

| (12) |

where rM, rD, and rT are fluorescence anisotropies of the monomer, dimer, and trimer. The quantities, fM, fD, and fT are the fractional contributions of the monomer, dimer, and trimer to the total emission of the sample, defined as

| (13a) |

| (13b) |

| (13b) |

and

| (13c) |

where FM, FD, and FTr are molar fluorescence intensities of the monomer and the trimer, respectively. As discussed above, one can take, FD = 2FM and FTr = 3FM in eqs. 13a – 13c. There are two independent parameters, KM and rD, which remain to be determined. The dashed line in Figures 1 is the best fit of the experimental curve using eqs. 8 – 13. It is clear that the reaction, which assumes the presence of a significant population of the dimer, does not adequately describe the experimental data (see Discussion).

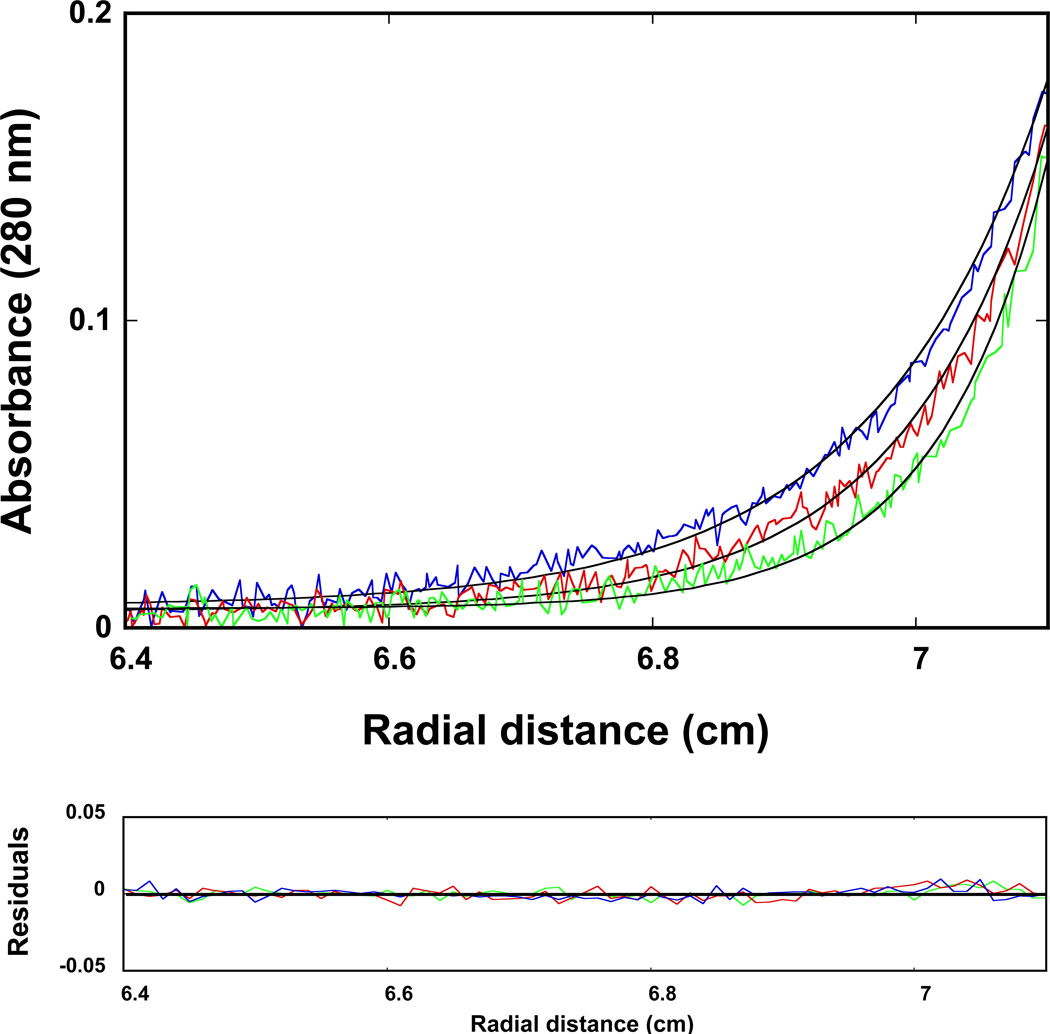

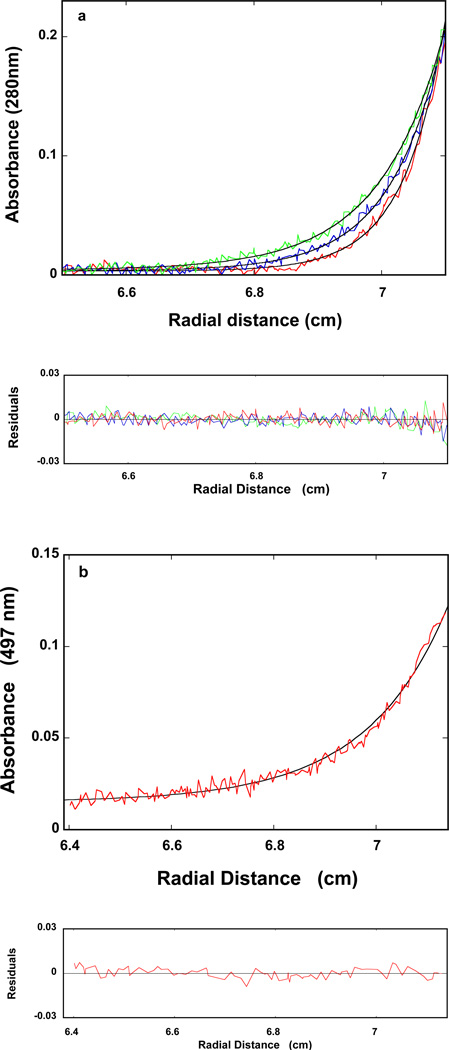

Sedimentation Equilibrium Studies of the DnaT Protein

The maximum stoichiometry of the DnaT oligomer, formed at the high protein concentrations, has been directly addressed using the sedimentation equilibrium method (41–44). Examples of the sedimentation equilibrium profiles of the DnaT protein in buffer C (pH 7.0, 25°C), recorded at the protein absorption band (280 nm) and at different rotational speeds, are shown in Figure 2. The selected protein concentration (2.86 × 10−6 M (monomer)) corresponds to the final plateau observed in the fluorescence anisotropy titration (Figure 1). The solid lines in Figure 2 are the nonlinear least-squares fits, using the single exponential function defined by eq. 2. The fits provide excellent descriptions of the experimental sedimentation profiles, indicating the presence of single species with the molecular weight of 55,000 ± 4000. Adding additional exponents does not improve the statistics of the fits (data not shown). The anhydrous molecular weight of the DnaT monomer is ~19,455 (15). Therefore, these results show that, at high protein concentrations, the DnaT protein exists as a specific and stable trimer in solution (see Discussion).

Figure 2.

Sedimentation equilibrium concentration profiles of the DnaT protein in buffer C (pH 7.0, 25°C). The concentration of the protein is 2.86 × 10−6 M (monomer). The profiles have been recorded at 280 nm and at 14000 (blue), 16000 (red), and 18000 (green) rpm. The smooth solid lines are the nonlinear least-squares fits to a single exponential function (eq. 2), with a single species having a molecular weight of 55000 (Materials and Methods). Lower panel shows the residuals of the fits.

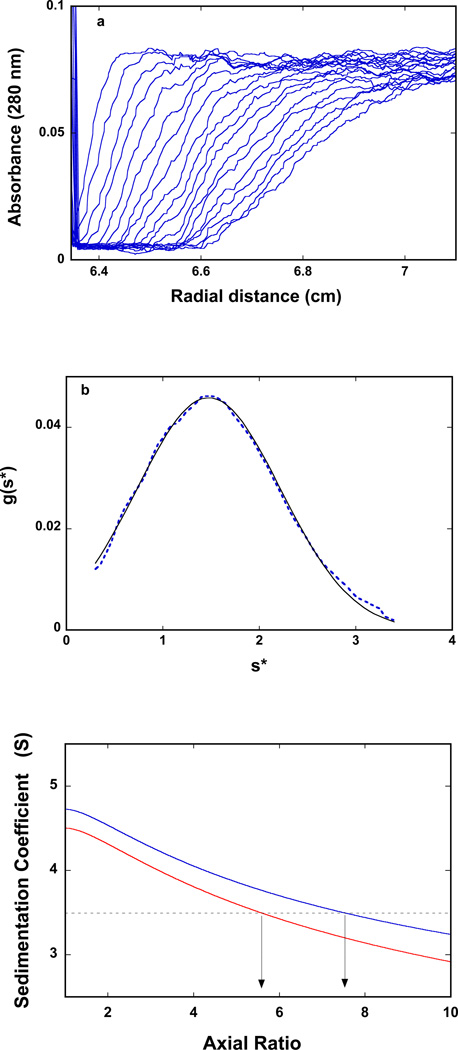

Global Conformation of the DnaT Protein Trimer in Solution

The sedimentation velocity profiles (monitored at 280 nm) of the DnaT in buffer C (pH 7.0, 25°C) are shown in Figure 3a. The concentration of the protein is 2.86 × 10−6 M (monomer). Inspection of the sedimentation profiles clearly shows that there is a single moving boundary, indicating the presence of a single molecular entity (40–43). To obtain the sedimentation coefficient of the protein, s20,w, the sedimentation velocity scans have been analyzed using the time-derivative approach as shown in Figure 3b (40–43,57,58). The value of s20,w shows little, if any, dependence upon the protein concentration, in the protein concentrations range (2.86 × 10−6 − 1.5 × 10−5 M (monomer)) where only the stable trimer is present (data not shown). The obtained value of the sedimentation coefficient of the DnaT protein is: so20,w = 3.5 ± 0.1 S (see Discussion).

Figure 3.

a. Sedimentation velocity absorption profiles at 280 nm of the DnaT protein in buffer C (pH 7.0, 25°C). The concentration of the DnaT is 2.86 × 10−6 M (monomer); 50000 rpm. b. Apparent sedimentation coefficient distribution, g(s*), as a function of the radial sedimentation coefficient coordinate, s*, obtained from the time derivatives of the DnaT protein sedimentation profiles recorded at 280 nm in buffer C (pH 7.0, 25°C); 50000 rpm. The solid line is the nonlinear least-squares fit of the distribution using the software provided by the manufacturer (Materials and Methods). c. Computer simulation of the sedimentation, so20,w, as a function of the axial ratio of the oblate ellipsoid of revolution, p, for different values of the degree of hydration, h (gH2O/gprotein) of the DnaT protein; 0.393 (blue) 0.240 (red). The plots have been generated using eqs. 14 – 15. The dashed horizontal line marks the value of the sedimentation coefficient, so20,w = 3.5 of the DnaT protein trimer. The arrows indicate values of the axial ratio, p, corresponding to the same so20,w at different degrees of hydration (see text for details).

The experimental values of so20,w, allows us to address the global shape of the DnaT trimer in solution (44,59). As we discussed below, the presence of the specific DnaT trimer and the fact that the isolated N-terminal core domain of the protein exclusively forms a dimer with a dramatically increased intrinsic affinity indicate that all three monomers are in contact with each other in the trimer (see below). Therefore, the simplest and physically realistic hydrodynamic model of the DnaT trimer is that of the oblate ellipsoid of revolution (44,59). Independently of any hydrodynamic models, the sedimentation coefficient is related to the average translational frictional coefficient, f̄p, of the protein by

| (14a) |

where M is the molecular weight of the anhydrous DnaT trimer and NA is the Avogadro number. For the oblate ellipsoid of revolution, f̄p is defined, in terms of the axial ratio, p (p = a/b, where a is the major axis of the ellipsoid) by the Perrin equation as (44)

| (14b) |

where Rh is the hydrodynamic radius of the corresponding hydrated sphere, defined as

| (15) |

η is the viscosity of the solvent (poise), h is the degree of the protein hydration expressed as gH2O/gprotein, and ν̄S is the partial specific volume of the solvent equal to the inverse of its density (44).

The degree of protein hydration, h, can be estimated by the Kuntz method (60). For the DnaT protein, it provides h ≈ 0.393 gH2O/gprotein. However, this value of h is calculated for the mixture of amino acids completely exposed to the solvent and represents the maximum possible value of the degree of hydration. Part of the amino acid residues is not accessible to the solvent in the native structure of the protein. Thus, the value of h should be corrected for the part of the residues in the native structure that is not accessible to the solvent. The correction factor can be obtained in a systematic way by comparing Kuntz's values for a series of proteins with the degree of hydration of the folded structure of the same protein (59,61). In the case of the DnaT protein, the correction factor amounts to ~0.61, thus, ~61% of the maximum values of h is associated with the protein molecule. The corrected value of the degree of hydration for the DnaT protein is then h = 0.240 gH2O/gprotein.

The computer simulation of the sedimentation coefficient, so20,w of the DnaT protein as a function of the axial ratio, p, of the oblate ellipsoid, using the corrected value of the degree of hydration, h, is shown in Figure 3c (59). For comparison, the dependence of so20,w as a function of the axial ratio of the oblate ellipsoid for the protein with the maximum degree of hydration (h = 0.393) is also included. For the corrected degree of hydration, the value of so20,w = 3.5 ± 0.1 S indicates that the DnaT protein trimer, in solution, has a very flat structure and behaves like a oblate ellipsoid of revolution with the apparent axial ratio of p = 7.5 ± 0.5. For the maximum hydrated protein, the same, apparent axial ratio is p = 5.6 ± 0.4 (Figure 3c) (see Discussion).

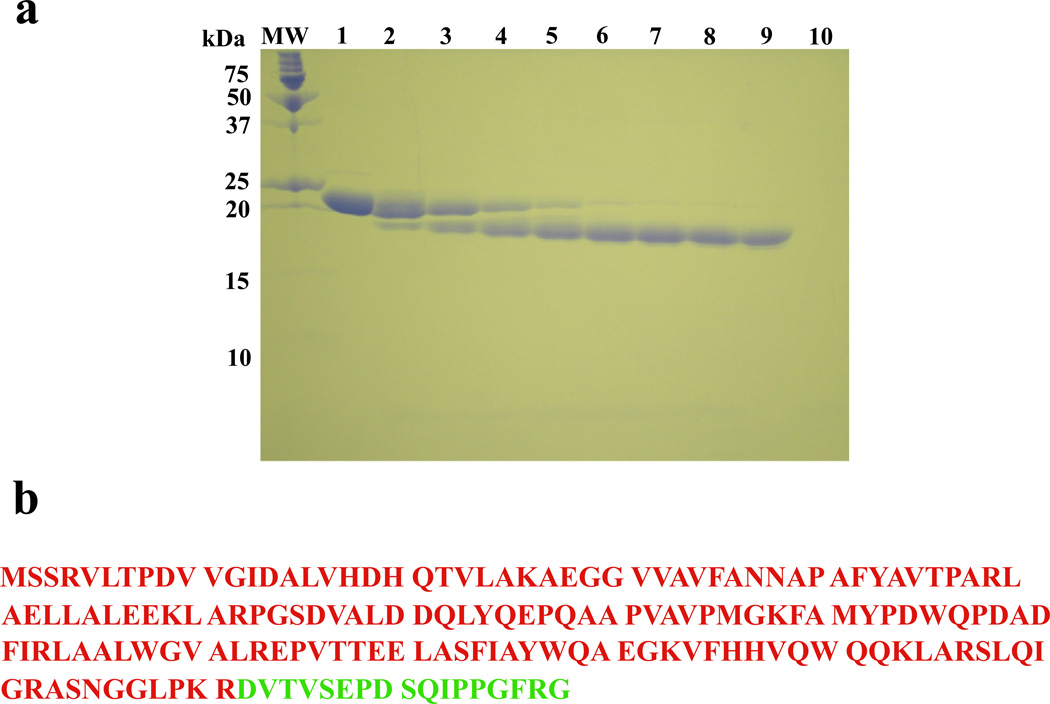

Domain Structure of the DnaT Protein Monomer

The flat global shape of the DnaT trimer indicates that the protein monomer also has an elongated shape and may be built of structural domains. Therefore, we address the domain structure of the DnaT protein using the protease digestion method (Materials and Methods) (16,27,28). Figure 4a shows the 15% polyacrylamide gel, stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, of the DnaT protein in the presence of trypsin, as a function of time. In the course of the reaction, the DnaT monomer band at ~19,500 kDa diminishes, while the smaller dominant band at ~17,000 kDa appears on the gel and after ~45 minutes of digestion reaction becomes the only species observed on the gel. Identical digestion reaction was performed with the protein variant, S3C (see below). The digestion products have been isolated by the column chromatography and analyzed, using amino acid sequencing and mass spectrometry (Materials and Methods), showing that the large dominant species is the N-terminal part of the protein of ~17100 kDa. The data indicate that the DnaT monomer is built of the large, N-terminal core domain, containing the first 161 amino acids from the N-terminus and a small C-terminal region containing the remaining 18 amino acids. The small C-terminal region was too small to the observed on the polyacrylamide gel (Figure 4a). The N-terminal core domain and the C-terminal region of the DnaT monomer, as reflected in the primary structure of the protein, are shown in Figure 4b (see Discussion).

Figure 4.

a. The SDS polyacrylamide gel (15%) of the DnaT protein subjected to the time-dependent trypsin digestion (buffer C, pH 7.0, 20°C) and stained with Coomasie Brilliant Blue (Materials and Methods). Lane MW contains the molecular markers. Lane 1 contains DnaT alone. Subsequent lanes contains DnaT-trypsin mixture (molar ratio = 140:1) at different times of the digestion reaction (min); lane 2, 5; lane 3, 10; lane 4, 20; lane 5, 30; lane 6, 45; lane 7, 60; lane 8, 90; lane 9, 120; lane 10, trypsin alone (details in text). b. Primary structure of the DnaT monomer with the N-terminal core domain and the small C-terminal region marked in different colors (15).

Oligomerization of the DnaT Protein N-Terminal Domain in Solution

To address the role of the N-terminal core domain and the small C-terminal region of the DnaT protein in the oligomerization reaction, we performed the steady-state fluorescence anisotropy titration of the isolated N-terminal core domain. As observed for the intact DnaT, the intensity of the fluorescence emission of the core domain is strictly proportional to the protein concentration, i.e., it is not affected by the monomer association reactions (data not shown), which facilitates titration analyses (see above). The dependence of the fluorescence anisotropy of the DnaT N-terminal core domain upon the total monomer concentration, in buffer C (pH 7.0, 20°C), is shown in Figure 5. The increase of the domain monomer concentration causes the increase of the anisotropy of the sample, from r ~0.055, at the monomer concentrations lower than ~1 – 2 × 10−8 M, to r ≈ 0.11 at protein concentrations > 2 × 10−6 M. Thus, the data show that the N-terminal domain undergoes an association reaction, from the species dominating at low [N-terminal core domain (monomer)] to a specific entity, which dominates the population at high protein concentrations (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The dependence of the DnaT N-terminal core domain fluorescence anisotropy upon the total domain monomer concentration (λex = 296 nm, λem = 347 nm) in buffer C (pH 7.0, 20°C) (Materials and Methods). The solid line is the nonlinear least-squares fit of the titration curve, using the dimer model described by eqs. 16 – 20, with KD = 2.1 × 107 M−1, rM = 0.055, and rT = 0.112. The dashed line is the best fit of the titration curve using monomer <-> trimer model described by eqs. 3 – 7, with KT = 2.5 × 1014 M−2, rM = 0.055, rD = 0.112.

The observed behavior is very similar to that of the intact DnaT protein (Figure 1), however, there is a dramatic difference. Inspection of the data in Figure 5 shows that the entire association curve spans ~3 orders of magnitude on the protein total monomer concentration scale, between 10% and 90% of the observed signal (35). As discussed above, such behavior provides the first indication that the observed association predominantly includes the monomer - dimer reaction (35). In other words, the N-terminal core domain does not form a trimer but a dimer (see below). The thermodynamic model, which describes the data, is defined by the equilibrium process, in which two molecules of the N-terminal domain associate forming a dimer, i.e.,

| (16) |

The equilibrium dimerization constant, KD, is defined as

| (17) |

The total monomer concentration of the N-terminal core domain, [M]T, is defined in terms of the free monomer [M]F and KD by the mass conservation expression as (47–56)

| (18) |

The observed fluorescence anisotropy of the system is then described by (35,36)

| (19) |

where rM and rD are fluorescence anisotropies of the domain monomer and the domain dimer, respectively. The quantities, fM and fD, are the fractional contributions of the monomer and the dimer to the total emission, i.e.,

| (20a) |

and

| (20b) |

where, FM and FDr are molar fluorescence intensities of the monomer and the dimer, respectively. In our case, FDr = 2FM in eqs. 20a and 20b. The solid line in Figure 5 is the nonlinear least-squares fit of the experimental titration curve, using eqs. 16 – 20. Both, rM and rD, can be estimated from the titration curve, leaving KD as an independent parameter. The fit provides, KD = (2.1 ± 0.5) × 107 M−1, with rM = 0.055 ± 0.001, and rD = 0.112 ± 0.001. For comparison, the dashed line in Figure 5 is the best fit of the experimental curve, using the trimer model, as described by eqs. 3 – 7. It is clear that the trimer model does not adequately describe the N-terminal domain association reaction (see Discussion).

Sedimentation Equilibrium Studies of the DnaT N-Terminal Core Domain Oligomeric State

The sedimentation equilibrium profile of the isolated DnaT N-terminal core domain in buffer C (pH 7.0, 20°C), recorded at the protein absorption band (280 nm) and different rotational speeds, is shown in Figure 6a. The protein concentration (2.14 × 10−6 M (domain monomer)) was selected on the basis of the final plateaus observed in the fluorescence anisotropy titrations (Figure 5). The smooth solid lines in Figure 6a are the nonlinear least-squares fits, using the single exponential function defined by eq. 2. The fits indicate the presence of a single species with the molecular weights of 32000 ± 3000. With the molecular weight of the DnaT N-terminal domain of ~17,100, the results show that, at high protein concentrations, the domain forms a dimer in solution (see Discussion).

Figure 6.

a. Sedimentation equilibrium concentration profiles of the isolated DnaT N-terminal core domain in buffer C (pH 7.0, 20°C). The concentration of the protein is 2.14 × 10−6 M (monomer). The profiles have been recorded at 280 nm and at 22000, 24000, and 26000 rpm. The smooth solid lines are the nonlinear least-squares fits to a single exponential function (eq. 2), with a single species having a molecular weight of 32000 (Materials and Methods). Lower panel shows the residuals of the fits. b. Sedimentation equilibrium concentration profiles of the fluorescein labeled N-terminal core domain of the DnaT variant, S3C, in buffer C (pH 7.0, 25°C). The concentration of the protein is 5.0 × 10−6 M (monomer). The profiles have been recorded at 497 nm and at 16000 rpm. The solid line is the nonlinear least-squares fit to a single exponential function (eq. 2), with a single species having a molecular weight of 35000 (Materials and Methods). Lower panel shows the residuals of the fits.

We have also addressed the final oligomeric state of the N-terminal core domain using the protein variant, S3C, labeled with fluorescein. The protein has been subjected to trypsin digestion (see above) and the reaction was stopped after 1 hour, using 1 mM PMSF. The sedimentation equilibrium profile of the DnaT N-terminal core domain, labeled with fluorescein, in buffer C (pH 7.0, 20°C), containing 1 mM PMSF, recorded at the fluorescein absorption band (497 nm), is shown in Figure 6b. The protein concentration is 5.0 × 10−6 M (domain monomer) (Figure 5). The solid line in Figure 6b is the nonlinear least-squares fit, using the single exponential function (eq. 2). The fit indicates the presence of a single species with the molecular weights of 35000 ± 3000. Thus, as observed for the unlabeled isolated domain, the fluorescein-labeled, DnaT N-terminal core domain forms a dimer in solution (see Discussion).

Global Conformation of the DnaT N-Terminal Core Domain Dimer

The sedimentation velocity profiles (monitored at 280 nm) of the DnaT N-terminal core domain in buffer C (pH 7.0, 25°C) are shown in Figure 7a. The concentration of the protein is 1.07 × 10−5 M (monomer), i.e., it corresponds to the plateau of the fluorescence anisotropy titration curve (Figure 5). Inspection of the sedimentation profiles clearly shows that there is a single moving boundary, indicating the presence of a single molecular entity (40–43). The sedimentation velocity scans have been analyzed using the time-derivative approach, as shown in Figure 7b (57–59). The dependence of s20,w upon the domain dimer concentration is shown in Figure 7c. The extrapolation to the zero concentration provides the corrected value of the sedimentation coefficient of the DnaT N-terminal core domain as, so20,w = 2.3 ± 0.1 S (Figure 7c).

Figure 7.

a. Sedimentation velocity absorption profiles at 280 nm of the DnaT N-terminal core domain in buffer C (pH 7.0, 25°C), containing 1 mM PMSF. The concentration of the DnaT is 1.07 × 10−5 M (monomer); 50000 rpm. b. Apparent sedimentation coefficient distribution, g(s*), as a function of the radial sedimentation coefficient coordinate, s*, obtained from the time derivatives of the DnaT N-terminal domain sedimentation profiles recorded at 280 nm in buffer C (pH 7.0, 25°C); 50000 rpm. The solid line is the nonlinear fit of the distribution using the software provided by the manufacturer (Materials and Methods). c. Dependence of the sedimentation coefficient of the DnaT N-terminal core domain upon the concentration of the protein (monomer). The solid line is the linear least-squares fit of the data, which provides so20,w = 2.3 ± 0.1 S (extrapolated dashed line). d. Computer simulation of the sedimentation, so20,w, as a function of the axial ratio of the oblate ellipsoid of revolution, p, for different values of the degree of hydration, h (gH2O/gprotein) of the DnaT N-terminal domain; 0.389 (blue) 0.235 (red). The plots have been generated using eqs. 14 – 15. The solid horizontal line marks the value of the sedimentation coefficient, so20,w = 2.3. The arrows indicate values of the axial ratio, p, corresponding to the same so20,w at different degrees of hydration (see text for details).

Analogously to the trimer, the hydrodynamic shape of the DnaT domain dimer, using the model of the oblate ellipsoid of revolution, has been addressed as discussed above (eqs. 14 and 15). The degree of hydration, h, estimated by the Kuntz method is 0.389 gH2O/gprotein (60). Correction for the part of residues in the native structure that is not accessible to the solvent provides h ≈ 0.235 gH2O/gprotein (59,61). The computer simulation of the sedimentation coefficient, so20,w of the N-terminal domain as a function of the axial ratio, p, of the oblate ellipsoid, using the corrected value of the degree of hydration, h, is shown in Figure 7d, together with the dependence of so20,w as a function of the axial ratio of the oblate ellipsoid for the protein with the maximum degree of hydration (h = 0.389 gH2O/gprotein) (59). For the corrected degree of hydration, the value of so20,w = 2.3 ± 0.1 S indicates that the core domain dimer, in solution, also has a very flat structure and hydrodynamically behaves like an oblate ellipsoid of revolution with the apparent axial ratio of p = 9.1 ± 0.5. For the maximum hydrated protein, the same axial ratio is p = 7.5 ± 0.6 (Figure 7d) (see Discussion).

DISCUSSION

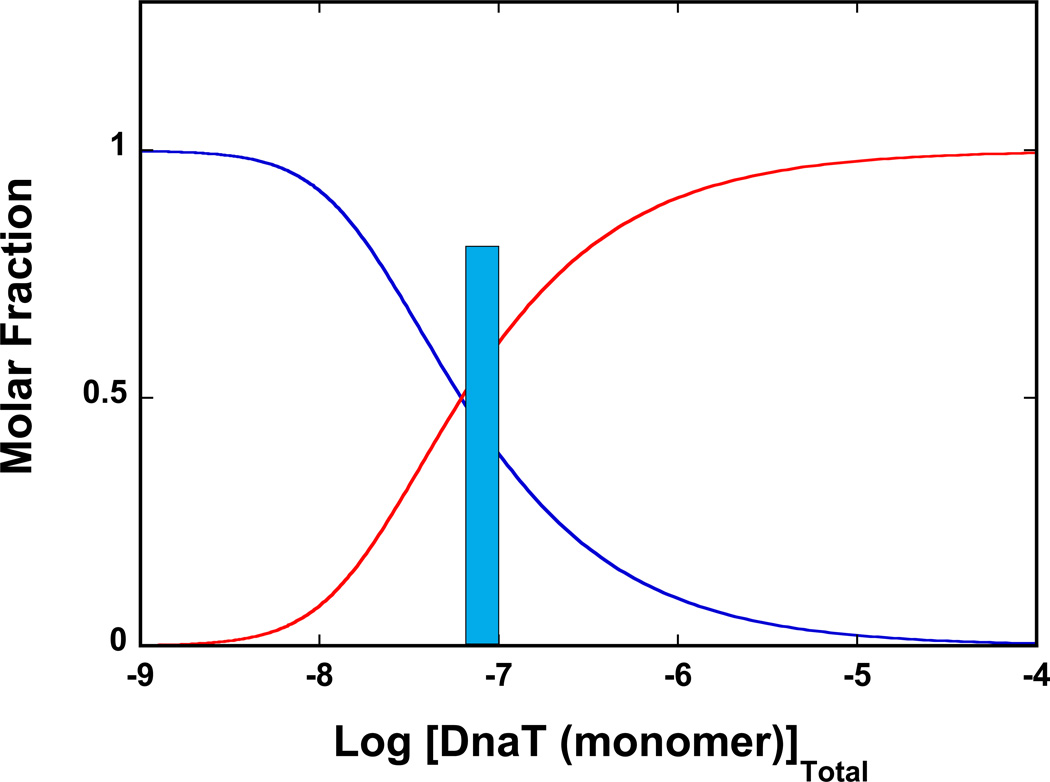

The DnaT Protein Forms a Monomer - Trimer Equilibrium System in Solution

In spite of the key role of the DnaT in the process of the primosome assembly, to our knowledge, the results reported in this work are the first quantitative analyses of the DnaT oligomerization process. Although the DnaT protein shows some propensity to aggregate at very high protein concentrations, the specific and largest oligomer of the protein is a homo-trimer (Figures 1 and 2). Nevertheless, the affinity of forming the trimer is rather modest and, as the protein concentration decreases below ~5 × 10−7 M (monomer), the trimer disintegrates into monomers. Figure 8 shows the dependence of the molar fractions of the DnaT monomer in the monomer and the trimer states as a function of the total monomer concentration, obtained using the determined trimerization constant, KT ≈ 3.5 × 1014 M−2. Because, in the presence of magnesium, KT is independent of the temperature (see accompanying paper), the distribution applies to all physiological temperatures. Thus, the trimer state dominates the population distribution at the total monomer concentration ≥ 5 × 10−7 M. In this context, the estimated total concentration of the DnaT monomer in the E. coli cell is ~8 × 10−8 M and is marked in Figure 8 (14). It is evident that, at the estimated concentration of the protein in the cell, the DnaT protein does not exclusively exist as a trimer, but as a 3:1 molar mixture of the monomer and trimer states.

Figure 8.

The dependence of molar fractions of the DnaT monomer in the monomer and the trimer state as a function of the total monomer concentration, obtained using eqs, 3 – 7 and the determined trimerization constant, KT ≈ 3.5 × 1014 M−2. The trimer state dominates the population distribution of the DnaT protein at the total monomer concentration ≥ 3 × 10−7 M. the estimated concentration of the DnaT monomer in the E. coli cell is ~8 × 10−8 M and is marked in the figure (14).

DnaT Trimerization is a Highly Cooperative Process

A surprising aspect of the observed DnaT trimerization reaction is that, in spite of the modest affinity, it is a high cooperative process. The oligomerization curve (Figure 1) is adequately described by the monomer <-> trimer equilibrium, characterized by a single equilibrium constant, KT. Nevertheless, with the exception of some extremely rare cases, chemical association reactions occur as bimolecular encounters, particularly at the concentration used in biochemical studies (62). In other words, the dimer must be present, although its population must be very low. In a more complex model, which includes two binding parameters, the intrinsic binding constant, KM, and cooperativity parameter, σ, the total concentration of the protein monomer is defined as (47–56)

| (21a) |

The cooperative interactions parameter, σ, describes the increased affinity of the association of the third monomer, resulting in the trimer formation. The very small population of the dimer indicates that in the DnaT system, σ is large and positive, and eq. 21a effectively reduces to eq. 5, as

| (21b) |

As we stated above, the high cooperativity of the system precludes any unique and independent determination of KM and σ, due to their highly correlated values. The nonlinear least-squares fit of the titration curve using the model defined by eq. 21a is shown in Figure 1. The plot has been obtained by setting a given value of KM and fitting σ and rD. The fit offers only the maximum possible value of the KM = (7 ± 1) × 105 M−1 and the minimum value of σ = 730 ± 100, which provide an adequate representation of the experimental data. For values of KM higher than its maximum value, the model (eq. 21a) ceases to represent the experimental titration curve (plot not shown). For any values of KM lower than its maximum value, a corresponding larger value of σ matches the value of KM. An example of such plot is included in Figure 1.

The DnaT Monomer Possesses Heterogeneous Binding Sites

Several conclusions concerning the DnaT protein can be deduced from the very fact that the protein forms a specific homo-trimer. Thus, formation of the trimer indicates that the monomer must possess heterogeneous interacting areas, i.e., at least two different interacting sites. The first two monomers, already engaged in the dimer through their interacting sites, must possess additional binding areas, which are able to accept the third monomer. Moreover, interactions of the third monomer, within the trimer, must be different from the interactions between the two remaining monomers (see below). The high cooperativity of the trimerization reaction strongly corroborates this last conclusion. Experiments with the N-terminal core domain, which exclusively forms a high-affinity dimer and the role of the C-terminal region in the trimerization reaction provide strong evidences for the heterogeneity of the DnaT monomer binding sites (see below).

The DnaT Monomer Is Built of a Large Core Domain and a Small C-Terminal Region and Possesses Two Binding Sites Located on the N-Terminal Core Domain and the C-Terminal Region of the Protein, Respectively

Trypsin digestion studies revealed that the DnaT protein is built of the large N-terminal core domain and the small C-terminal region (Figures 4a and 4b). Theoretical analysis of secondary structure of the 18 amino acid sequence of the C-terminal domain indicates that it is a flexible, unstructured entity within the protein structure (data not shown). Yet, the removal of the C-terminal domain dramatically affects the oligomerization of the DnaT protein. Instead of the specific trimer, a specific dimer of the N-terminal core domain is formed (Figure 5). There are two fundamental aspects of these results. First, one of the monomer-binding sites is located on the large N-terminal domain, which allows the monomers to form the core-domain dimer, while the small C-terminal region forms the other binding site. Second, the third monomer in the trimer is associated with the remaining two monomers through the C-terminal regions, not through the N-terminal core domains, which in the dimer are already engaged in interactions.

In the DnaT Trimer, Each Monomer is in Contact with Two Other Monomers

Another aspect of the high specificity of the DnaT trimerization reaction, i.e., the absence of any oligomers larger than the homo-trimer, indicates that each monomer in the DnaT trimer is in contact with the remaining two monomers. If a linear oligomer were formed, resulting in a specific homo-trimer structure with only nearest-neighbor interactions, then this would imply that one of the monomers has two interacting areas to engage the other two monomers, while the other two monomers do not have that capacity. Because the monomers are identical, such a linear model would require a very peculiar and profound, conformational transition of at least one of the monomers involving its C-terminal region. It would also require a strong spatial separation of the C-terminal region from the interacting of the initially formed dimer, at least through the distance of one monomer. However, it would not explain why the removal of the C-terminal region, far from the interacting areas in the initial dimer, dramatically increases the affinity of the dimer of the isolated N-terminal core domain (Figure 5).

Notice, if the DnaT trimer were a linear oligomer and modeled as a corresponding prolate ellipsoid of revolution, then for so20,w = 3.5 ± 0.1 S, its axial ratio would be p ≈ 6.5 (data not shown). For a linear oligomer, this would mean that the axial ratio of the corresponding linear dimer of the same protein is p ≈ 4.3. Yet, the axial ratio of the N-terminal core domain dimer with so20,w = 2.3 ± 0.1 S, when modeled as a prolate ellipsoid of revolution, is p ≈ 7.8 (data not shown). Clearly, the linear dimer/trimer model does not adequately describe hydrodynamic behavior of the DnaT protein. Furthermore, removal of the C-terminal region does not eliminate the ability of the monomer to interact with the other monomer and to form a dimer (Figure 5). Contrary, the intrinsic affinity within the domain dimer is considerably higher than between monomers in the trimer. This indicates that the small C-terminal regions, in the intact monomers, hinder the interactions and are close to the interacting areas of the monomers in the dimer, i.e., close to the center of the formed, initial dimer molecule. The dimer of the N-terminal core domain lacks the binding site for the third monomer and this binding site must involve the C-terminal regions of all three monomers (see below).

High Affinity of the N-Terminal Core Domain Dimer Indicates That the DnaT Monomer Undergoes a Conformational Transition Upon Oligomerization, Involving the Small C-Terminal Region

The high affinity of the isolated N-terminal core domain is striking. Interactions between monomer in the domain dimer are characterized by KD = (2.1 ± 0.5) × 107 M−1 (Figure 5), i.e., ΔGD° ~ − 9.8 kcal/mol, while the average free energy of interactions among the monomers in the trimer, with KT = (3.5 ± 0.5) × 1014 M−2, is (1/3) ΔGT° ~ − 6.5 kcal/mol (Figure 1). Also, the high cooperativity of the trimerization indicates that KD cannot be the intrinsic affinity, KM, of the DnaT monomers in the trimer (eqs. 11 and 21a). With (eq. 21b) the value of KD = KM (eqs. 11 and 21a) would imply that σ ≈ 0.8. Such a value of σ would produce a negatively cooperative trimerization process, instead of a strongly positive cooperative reaction, as experimentally observed (Figure 1) (47–56). Moreover, the maximum possible value of KM is ~ 7 × 105 M−1, i.e., approximately two orders of magnitude lower than KD characterizing the N-terminal domain dimer (Figure 1, see above). The removal of the small C-terminal region clearly and dramatically increases the intrinsic affinity of the interacting site located on the core domain. This behavior reinforces the conclusion that in the intact DnaT monomer, the flexible C-terminal region blocks the binding site located on the N-terminal domain, resulting in its diminished intrinsic affinity, as compared to the affinity of the isolated domain (see below). The results indicate that formation of the initial dimer of the intact protein induces a conformational transition, at the energetic expense of the intrinsic binding process, which takes away the C-terminal domain and sets it up for engagement of the third monomer in the trimer. The entire process is controlled by magnesium cations binding (accompanying paper).

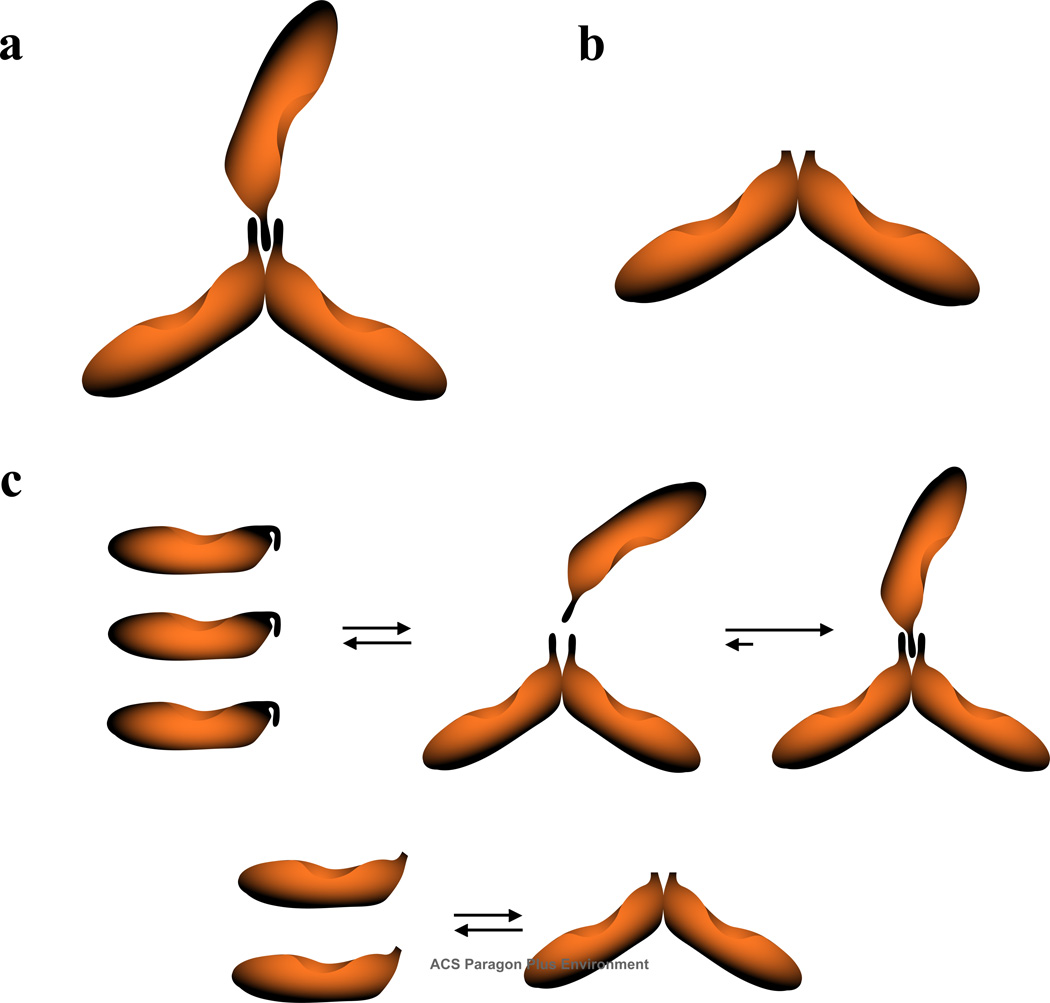

Models of the DnaT Trimer Structure

The discussion above and the analysis of the hydrodynamic behavior of the DnaT trimer and the N-terminal core domain dimer allow us to propose a model of the DnaT trimer structure based on the obtained results and the general theoretical analysis of the hydrodynamic properties of the monomer and the oligomers (63). First, because of the very low concentration of the protein, where the monomer dominates the population distribution (< 5 × 10−8 M (monomer)), we could not directly determine the sedimentation coefficient and the shape of the DnaT monomer. Nevertheless, we can get insight as to the shape of the monomer based on the sedimentation data of the DnaT trimer and the N-terminal core domain.

The very flat structures of the DnaT trimer and the N-terminal domain dimer, with the hydrodynamic axial ratios of p ≈ 7.5 and p ≈ 9.1, respectively, indicate that the monomers must have an elongated structure. For the simpler structure of the domain dimer, the value of p ≈ 9.1 indicates that the monomer has the minimal axial ratio of p ≈ 4.5 (43,45,59). The small and flexible C-terminal region will not affect this global hydrodynamic property. With the axial ratio of ~4.5, the sedimentation coefficient of the monomer of ~17,100 kDa and modeled as a prolate ellipsoid of revolution, is ~1.69 S (43,59,63). The ratios of the sedimentation coefficients of the dimer - monomer and trimer - monomer are then ~1.36 and ~2.07, respectively. Theoretical dependences of the sedimentation ratios of the monomers and corresponding dimer and trimer structures have been thoroughly described by Andrews and Jeffrey (63). Using their results, one obtains that the DnaT trimer has a global structure very close to the CTV-type assembly and the dimer of the N-terminal core domain has a global structure very close to the HR90 complex (63). No other structures are similarly compatible with the obtained sedimentation ratios. Moreover, the CTV structure of the trimer results from the attachment of the third monomer molecule to the HR90-type dimer in the center of the dimer molecule, without any rearrangement of the protomers. This is exactly what the thermodynamic and hydrodynamic data indicate for the formation of the DnaT trimer. These global structures of the DnaT trimer and dimer are schematically depicted in Figures 9a and 9b.

Figure 9.

a. Schematic representations of the global structures of the DnaT trimer and dimer obtained on the basis of the thermodynamic and hydrodynamic analyses discussed in this work, and the theoretical analysis of the monomer - oligomer sedimentation ratios (63) (details in text). b. Major aspects of the DnaT trimerization and the N-terminal core domain dimerization reactions. At a very low DnaT protein concentration, where the protein is in monomeric state, the small C-terminal region blocks access to the binding site located on the N-terminal core domain. Upon formation of the initial dimer, the protein undergoes a conformational transition, at the expense of the intrinsic binding energy, which frees the site on the N-terminal core domain from the C-terminal region. The third monomer engages the two associated monomers in interactions through the C-terminal domains. In the case of the isolated, N-terminal core domain, the small C-terminal region is missing and the domain forms a specific dimer with increased intrinsic affinity (details in text).

Figure 9c shows the major aspects of the DnaT trimerization and the N-terminal domain dimerization reactions, based on analyses presented in this work. At a very low protein concentration, the flexible C-terminal region is blocking the access to the binding site located on the N-core terminal domain in the free DnaT monomer. Data discussed in the accompanying paper indicated that, in fact, the C-terminal region interacts with the N-terminal core domain, affecting the enthalpy of the trimerization reaction. Upon formation of the initial dimer, the protein undergoes a conformational transition at the expense of the intrinsic binding energy, which frees the binding site on the N-terminal core domain from the C-terminal region. The two C-terminal regions in the dimer form a binding site for the third monomer. Thus, the third monomer engages two other monomers in interactions, mediated through the C-terminal regions of all three monomers. In the case of the isolated N-terminal core domain, the small C-terminal region is missing and the protein forms a specific dimer through the remaining binding site located on the core domain. The process is characterized by strongly increased intrinsic affinity, as the C-terminal region is not blocking the access to the binding sites (Figure 9c).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We wish to thank Mrs. Gloria Drennan Bellard for reading the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DEAE cellulose

Diethylaminoethyl cellulose

- PMSF

Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- SDS

Sodium dodecyl sulphate

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH Grant GM46679 (to W. B.). M. R. S. was partially supported by J. B. Kempner postdoctoral fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kornberg A, Baker TA. DNA Replication. San Francisco: Freeman; 1992. pp. 275–293. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenbaum JH, Marians KJ. Mutational Analysis of Primosome Assembly Site. Evidence For Alternative Structures. J Biol. Chem. 1985;260:12266–12272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng JY, Marians KJ. The Ordered Assembly of the fX174 Primosome. II. Preservation Primosome Composition From Assembly Through Replication. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:15649–15655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sangler SJ. Requirements for Replication Restart Proteins During Constitutive Stable DNA Replication in Escherichia coli K-12. Genetics. 2005;169:1799–1806. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen GC, Kornberg A. Assembly of the Primosome of DNA Replication in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:19204–19209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arai K, Arai N, Shlomai J, Kornberg A. Replication of the Duplex DNA of Phage PhiX174 Reconstituted with Purified Enzymes. Proc. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;77:3322–3326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heller RC, Marians KJ. Replication Fork Reactivation Downstream of the Blocked Nascent Leading Strand. Nature. 2006;439:557–562. doi: 10.1038/nature04329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heller RC, Marians KJ. Non-Replicative Helicases at the Replication Fork. DNA Repair. 2007;6:945–952. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szymanski MR, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Binding of Two PriA - PriB Complexes to the Primosome Assembly Site Initiates the Primosome Formation. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;411:123–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szymanski MR, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. The E. coli PriA Helicase Specifically Recognizes Gapped DNA Substrates. Effect of the Two Nucleotide-Binding Sites of the Enzyme on the Recognition Process. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:9683–9696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.094789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wickner S, Hurwitz J. Association of phiX174 DNA-dependent ATPase Activity With an Escherichia coli Protein, Replication Factor Y, Required for in vitro Synthesis of phiX174 DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA. 1975;72:3342–3346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marians KJ. PriA: At the Crossroads of DNA Replication and Recombination. Prog Nucleic Acid Res, Mol. Biol. 1999;63:39–67. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60719-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Nurse P, Marians K. The Ordered Assembly of the ϕX174 Primosome. III. PriB Facilitates Complex Formation Between PriA and DnaT. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:15656–15661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arai K, McMacken R, Yasuda S, Kornberg A. Purification and Properties of Escherichia coli Protein i a Prepriming Protein in fX174 DNA Replication. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:5281–5286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masai H, Bond M, Arai K. Cloning of the Escherichia coli gene for Primosomal Protein i: The Relationship to DnaT, Essential for Chromosomal DNA Replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:1256–1260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szymanski MR, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. The Escherichia coli PriA Helicase - Double-Stranded DNA Complex. Location of the Strong DNA-Binding Subsite on the Helicase Domain of the Protein and the Affinity Control By the Two Nucleotide-Binding Sites of the Enzyme. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;402:344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jezewska MJ, Szymanski MR, Bujalowski W. The Primary DNA-Binding Subsite of the Rat Pol β Energetics of Interactions of the 8-kDa Domain of the Enzyme With the ssDNA. Biophys. Chem. 2011;156:115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szymanski MR, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Interactions of the Escherichia coli Primosomal PriB Protein with the Single-Stranded DNA. Stoichiometries, Intrinsic Affinities, Cooperativities, and Base Specificities. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;398:8–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski PJ, Bujalowski W. Interactions of the DNA Polymerase X of African Swine Fever Virus with Double-Stranded DNA. Functional Structure of the Complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;373:75–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcinowicz A, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski PJ, Bujalowski W. The Structure of the Tertiary Complex of the RepA Hexameric Helicase of Plasmid RSF1010 with the ssDNA and Nucleotide Cofactors in Solution. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13279–13296. doi: 10.1021/bi700729k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski PJ, Bujalowski W. Interactions of the DNA Polymerase X From African Swine Fever Virus with Gapped DNA Substrates. Quantitative Analysis of Functional Structures of the Formed Complexes. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12909–12924. doi: 10.1021/bi700677j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edeldoch H. Spectroscopic Determination of Tryptophan and Tyrosine in Proteins. Biochemistry. 1967;6:1948–1954. doi: 10.1021/bi00859a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill SC, von Hippel PH. Calculation of Protein Extinction Coefficients From Amino Acid Sequence Data. Anal. Biochem. 1989;182:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jezewska MJ, Rajendran S, Bujalowski W. Functional and Structural Heterogeneity of the DNA Binding Site of the Escherichia coli Primary Replicative Helicase DnaB Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:9058–9069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jezewska MJ, Rajendran S, Bujalowska D, Bujalowski W. Does ssDNA Pass Through the Inner Channel of the Protein Hexamer in the Complex with the E. coli DnaB Helicase? Fluorescence Energy Transfer Studies. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:10515–10529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jezewska MJ, Galletto R, Bujalowski W. Rat Polymerase β Gapped DNA Interactions: Antagonistic Effects of the 5' Terminal PO4- Group and Magnesium on the Enzyme Binding to the Gapped DNAs with Different ssDNA Gaps. Cell Biochem. and Biophys. 2003;38:125–160. doi: 10.1385/CBB:38:2:125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shea MA, Sorensen BR, Pedigo S, Verhoeven AS. Proteolitic Footprinting Titrations for Estimating Ligand-Binding Constants and Detect Pathways of Conformational Switching of Calmofulin. Meth. Enzym. 2000;323:254–301. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)23370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorensen BR, Faga LA, Hultman R, Shea MA. Mutation of Tyr38 Disrupts the Structural Coupling Between the Opposite Domains in Vertebrate Calmodulin. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szymanski MR, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Interactions of the Escherichia coli Primosomal PriB Protein with the Single-Stranded DNA. Stoichiometries, Intrinsic Affinities, Cooperativities, and Base Specificities. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;398:8–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roychowdhury A, Szymanski MR, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Interactions of the E. coli DnaB - DnaC Protein Complex With Nucleotide Cofactors. 1. Allosteric Conformational Transitions of the Complex. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6712–6729. doi: 10.1021/bi900050x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roychowdhury A, Szymanski MR, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Mechanism of NTP Hydrolysis by the Escherichia coli Primary Replicative Helicase DnaB Protein. 2. Nucleotide and Nucleic Acid Specificities. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6730–6746. doi: 10.1021/bi9000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jezewska MJ, Rajendran S, Bujalowski W. Escherichia coli Replicative Helicase PriA Protein - Single-Stranded DNA Complex. Stoichiometries, Free Energy of Binding, and Cooperativities. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:27865–27873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Interactions of Escherichia coli Replicative Helicase PriA Protein with Single-Stranded DNA. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10454–10467. doi: 10.1021/bi001113y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lucius AL, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. The Escherichia coli PriA Helicase Has Two Nucleotide-Binding Sites Differing in Their Affinities for Nucleotide Cofactors. 1. Intrinsic Affinities, Cooperativities, and Base Specificity of Nucleotide Cofactor Binding. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7202–7216. doi: 10.1021/bi051826m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bujalowski W, Lohman TM. Monomer-Tetramer Equilibrium of the E. coli SSB-1 Mutant Single Strand Binding Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:1616–1626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lakowicz JR. Principle of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. New York: Kluwer Academc/Plenum Publishers; 1999. pp. 291–319. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailey MF, Van der Schans EJ, Millar DP. Dimerization of the Klenow Fragment of Escherichia coli DNA Polymerase I Is Linked to Its Mode of DNA Binding. Biochemistry. 2007;46:885–899. doi: 10.1021/bi6024148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LiCata VJ, Wowor AJ. Applications of Fluorescence Anisotropy to the Studies of Protein-DNA Interactions. Methods Cell. Biol. 2008;84:243–262. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)84009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Royer CA, Scarlata SF. Fluorescence Approaches to Quantifying Biological Interactions. Meth. Enzym. 2008;450:79–106. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galletto R, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Interactions of the E. coli DnaB Helicase Hexamer with the Replication Factor the DnaC Protein. Effect of Nucleotide Cofactors and the ssDNA on Protein-Protein Interactions and the Topology of the Complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;329:441–465. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00435-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcinowicz A, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Multiple Global Conformational States of the Hexameric RepA Helicase of Plasmid RSF1010 With Different ssDNA-Binding Capabilities Are Induced By Different Numbers of Bound Nucleotides. Analytical Ultracentrifugation and Dynamic Light Scattering Studies. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;375:386–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bujalowski W, Klonowska MM, Jezewska MJ. Oligomeric Structure of Escherichia coli Primary Replicative Helicase DnaB Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:31350–31358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Global Conformational Transitions in E. coli Primary Replicative DnaB Protein Induced by ATP, ADP and Single-Stranded DNA Binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:4261–4265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cantor RC, Schimmel PR. Biophysical Chemistry. Vol. II. New York: W. H. Freeman; 1980. pp. 591–641. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JC, Timasheff SN. The Calculation of Partial Specific Volumes of Proteins in 6 M Guanidine Hydrochloride. Meth. Enzym. 1979;61:49–51. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)61006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heyduk T, Lee JC. Application of Fluorescence Energy Transfer and Polarization to Monitor Escherichia coli CMP Receptor Protein and Lac Promoter Interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:1744–1748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bujalowski W. Thermodynamic and Kinetic Methods of Analyses of Protein – Nucleic Acid Interactions. From Simpler to More Complex Systems. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:556–606. doi: 10.1021/cr040462l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lohman TM, Bujalowski W. Thermodynamic Methods for Model-Independent Determination of Equilibrium Binding Isotherms for Protein-DNA Interactions: Spectroscopic Approaches to Monitor Binding. Meth. Enzym. 1991;208:258–290. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)08017-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. A General Method of Analysis of Ligand Binding to Competing Macromolecules Using the Spectroscopic Signal Originating from a Reference Macromolecule. Application to Escherichia coli Replicative Helicase DnaB Protein-Nucleic Acid Interactions. Biochemistry. 1998;35:2117–2128. doi: 10.1021/bi952344l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bujalowski W, Jezewska MJ. Thermodynamic Analysis of the Structure-Function Relationship in the Total DNA-Binding Site of Enzyme - DNA Complexes. Meth. Enzym. 2009;466:294–324. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)66013-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bujalowski W, Jezewska MJ. Macromolecular Competition Titration Method: Accessing Thermodynamics of the Unmodified Macromolecule-Ligand Interactions Through Spectroscopic Titrations of Fluorescent Analogs. Meth. Enzym. 2011;488:17–57. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381268-1.00002-1. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hill TL. Cooperativity Theory in Biochemistry. Steady-State and Equilibrium Systems. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985. pp. 167–234. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stafford W., III Boundary Analysis in Sedimentation Transport Experiments: a Procedure for Obtaining Sedimentation Coefficient Distributions Using the Time Derivative of the Concentration Profile. Anal. Biochem. 1992;203:295–301. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90316-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Correia JJ, Chacko BM, Lam SS, Lin K. Sedimentation Studies Reveal a Direct role of Phosphorylation in Smad3:Smad4 Homo- and Hetero-Dimerization. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1473–1482. doi: 10.1021/bi0019343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galletto R, Maillard R, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Global Conformation of the Escherichia coli Replication Factor DnaC Protein in Absence and Presence of Nucleotide Cofactors. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10988–11001. doi: 10.1021/bi049377y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuntz ID. Hydration of Macromolecules. III. Hydration of Polypeptides. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 1971;93:514–515. doi: 10.1021/ja00731a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bull HB, Breese K. Protein Hydration. I. Binding Sites. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968;128:488–496. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moore JW, Pearson RG. Kinetics and Mechanism. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1981. pp. 83–136. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Andrews PR, Jeffrey PD. Calculated Sedimentation Ratios for Assemblies of Two Three, Four, and Five Spatially Equivalent Protomers. Biophys. Chem. 1980;11:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(80)85007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]