Abstract

Liver disease has evolved into a complex discipline with several tiers of service delivery. Patients’ needs vary at different phases of their disease, with mobility between local hospitals and specialist centres being increasingly common. Liver transplantation requirements serve as a good illustration of this fluidity and the need for service providers to coordinate care delivery. This is facilitated by the development of networks and satellite relationships that can range in complexity and functionality.

Keywords: Liver, Liver Transplantation, Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Clinical Decision Making

Introduction

Liver disease in the UK has been considered to be a cinderella speciality and an off-shoot of gastroenterology. Liver services were not developed prospectively to reflect the epidemiology of liver disease or variations in disease burden or complexity. Nor were they developed to map patient needs efficiently to a logical geographical distribution of services. Instead, liver services developed around a generation of clinicians who trained in one of the fortresses of hepatology in the capital—the Royal Free Hospital and King's College Hospital. In parallel, liver transplant service development reflected the ambition of individuals and institutions rather than a business-like assessment of need.

A considerable component of liver disease is managed to a high standard by gastroenterologists or gastroenterologists with a professed interest in liver disease. However, liver disease can become very complex and take these same gastroenterologists out of their comfort zone quite quickly. In the traditional manner help was then sought from specialist liver units, with the expectation that patients would be rapidly transferred to these facilities, possibly never to return to base services. Two types of specialist units developed, one based around liver transplantation services and the other around groups of specialists with core competencies to deal with all aspects of complex liver disease short of transplant services. The latter in turn developed relationships with liver transplant programmes to meet that need for their patients.

A range of working relationships has developed that extends beyond the conventional referral of individual patients on an ‘as-needs’ basis. These range greatly in complexity and functionality. There are two basic requirements to underpin a successful partnership—critical mass of patients and bilateral enthusiasm. Given the right circumstances and support such relationships can develop unrecognised levels of potential to promote excellence in cooperation and patient care, as will be illustrated later.

Outreach clinics

This model involves specialists attending clinics to replicate the level of service that a patient and their family would receive at the base institution. Geographical considerations tend to be a driver of these arrangements and they tend to concentrate on specialised clinical conditions. Paediatric liver disease and liver transplantation are two of the more visible example of this type of arrangement. Outreach clinics in isolation are not networks but could be the basis for progressing to that level.

Basic networks

Disease specific

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a leading example of a disease-specific network based on multidisciplinary meetings (MDM). The vast majority of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma have coexisting cirrhosis, and the evaluation of each patient includes an assessment of both diseases in parallel. Each patient should be assessed specifically with respect to suitability for:

partial hepatectomy

liver transplantation

potentially curative ablation

-

locoregional therapy

as primary therapy

as a bridge to potentially curative intervention

biological agents, for example, sorafenib

clinical trials.

The hepatological evaluation should address the impact of the severity of the liver disease on these treatment options as well as the potential for recompensation. This mainly relates to the possibility that liver disease might improve with abstinence from alcohol or control of hepatitis B replication. Finally, input should be available from a palliative care service.

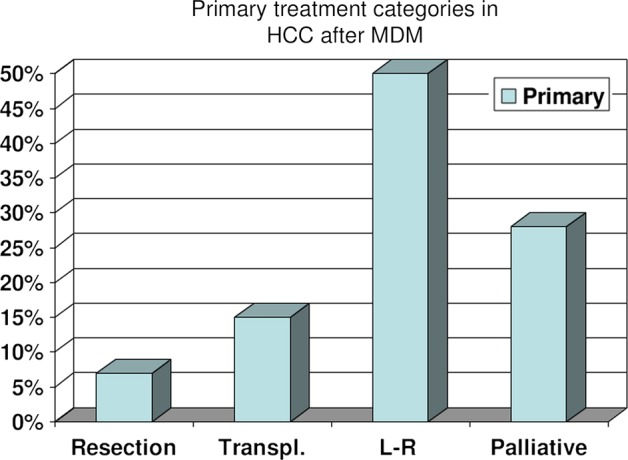

The primary therapeutic intervention assigned for patients being discussed at our MDM is shown in figure 1. Almost a quarter of patients are offered some form of surgery, with two being listed for liver transplantation for each one offered liver resection. The single largest cohort is assigned to an ablative technique, a locoregional therapy (chemoembolisation being the usual primary intervention) or a combination of both. Some patients are suitable only for palliative care unless there is scope for recompensation of the underlying liver disease.

Figure 1.

The outcome of the initial assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) by a multidisciplinary meeting (MDM) with respect to treatment categorised as resection, liver transplantation, locoregional (L-R) therapies and biological agents or palliation.

The expertise to deliver this comprehensive evaluation will not necessarily reside within an individual institution. Equally, not all cases will need to be formally reviewed by a centre offering liver transplantation. However, the network arrangement should ensure that all the appropriate therapeutic options are considered and that there is transparency regarding the decision-making process.

Service specific

Liver transplantation is a leading example of a service that has driven the development of networks. A fundamental difference between an outreach clinic and a network is local empowerment in the assessment and decision-making process. Ideally, this empowerment should be progressive and generate a confidence in the local team (junior medical staff, specialist nurses, ward-based nursing staff, service managers) so as to optimise its potential. Trust is another critical component of this process, both from the perspective of the patient as well as between the clinicians from the participating institutions. The patient experience should be of an encounter that does not compromise their options in any way but rather eases them through the first stages of the procedure in a familiar environment.

How far can the network process extend?

The King's College experience is that there should be no predetermined limit to how sophisticated network arrangements can become. This is based on networks based in Plymouth serving the peninsula and Belfast serving Northern Ireland. In each case there was a clearly defined need based on geographical ‘remoteness’ coupled with a local enthusiast. Without the absolute commitment from senior clinicians in Belfast and Plymouth these networks would never have got off the ground. This was combined with an institutional and personal commitment from the host institution to support the development of the service. In both instances, liver transplantation needs drove cooperation between the institutions but the timing and scope of the relationship differed. In the peninsula, the initiative occurred 2 years into the evolution of a more general hepatology network set up to deliver high quality liver services in an area previously devoid of them. In Northern Ireland, growth was more organic and was coupled with enhanced levels of cooperation with previously established services, especially hepatobiliary surgery. As services developed additional hepatological and related appointments were made in Belfast and Plymouth, and both centres have been very successful in developing feeder networks within their territories. Crucially, and most impressively, the quality of overall liver services has improved beyond all recognition in these regions.

Liver transplantation is again a good example to illustrate the extent to which the process of empowerment can result in transfer of care to the network spoke. A patient navigating the transplant pathway may have all care delivered locally apart from potentially as little as 1 day preoperatively and 5–7 days postoperatively at the network hub. The main interface for communication is four to eight joint clinical days per year, with clinicians from King's travelling to Belfast or Plymouth. A typical joint clinical day will involve up to 40 clinical episodes spread across inpatient reviews, outpatients, MDM discussions and reviews in abstentia. This is supported by weekly teleconferencing at present, but the potential for developing this level of communication is as yet underdeveloped. The roles undertaken by the two components of the network are detailed in table 1.

Table 1.

Service provision across network components in liver transplantation

| Activity | Belfast and Plymouth | London |

|---|---|---|

| Discussion in principle | Teleconference or joint clinic | |

| Transplant assessment | Full agreed protocol | |

| Completion of assessment | Teleconference | Anaesthetic and surgical review |

| Education and orientation | ||

| Wait-list management | Total delivery of care | |

| Transplant episode | Surgery and first week | |

| Inpatient care after day 7 | ||

| Interventional endoscopy and radiology | Support in complex cases | |

| Histology of liver biopsy | All samples reviewed | |

| Outpatient follow-up | Local and joint clinics | |

| Post-transplant surgery | Biliary reconstruction, etc. (Plymouth patients) | Biliary reconstruction, etc (Belfast patients) |

What is in it for the patient?

Delivery of healthcare in a local and familiar environment is intuitively a winning concept that is readily understood and accepted at a practical level. Few patients and even fewer family members see merit in travel to receive treatment if it can be delivered locally. Few healthcare quality assessors would fail to recognise the importance of support from family and friends during the treatment process. However, patients need to be confident that the service they are getting is enhanced rather than compromised. Against a background of very positive patient feedback in Belfast, a sentiment is often articulated of an attachment and loyalty to Kings that is not always fulfilled by the devolved service arrangement. Sensitivity to this undercurrent should enhance patient satisfaction. The relationship with the patient can also be recognised through patient associations as, again, exemplified by the excellent Royal Victoria Hospital group. Finally, but at a very practical level from the patient perspective, in the network they get to see at least two consultants per encounter as opposed to a different registrar most times they go for an outpatient review at the hub institution.

What is in it for the ‘spoke’?

The twin concepts of empowerment and service development have already been highlighted and these are obvious advantages when they realise local ambition. Protocols can be adopted from the hub and carried out to an agreed standard that minimises duplication of effort, for example, transplant assessment. The network model also helps to extend the undervalued idea of continuity of care and longitudinal patient/professional relationship. With time, a bond may develop between the hub and spoke that extends beyond the core personnel and original intent, which, if recognised, can be harnassed to provide support in many ways. Examples of this concept in action include initiatives in audit, teaching and research.

What is in it for the ‘hub’?

The model of care that intended to deliver care for life after liver transplantation is both unsustainable and outdated. The increase in the number of patients living with liver grafts has or will soon outgrow facilities at the seven transplant centres. There is a need to decant some of the activity away from the host institution without severing the relationship. The training curriculum has become more responsive to subspeciality training and exposure in hepatology, and this will be a valued resource in the development of networks. The network model is also a highly efficient way of exposing senior clinicians to patients leading to enhanced job satisfaction.

How do I start a network relationship?

The first thing to understand is that the initiative to start a networking relationship usually comes from the ‘spoke’ to be. The second is that the potential to develop these relationships is considerable and often unrecognised. A check list of preliminary questions is suggested in table 2 by way of starting the evaluation process. History indicates that the approach most likely to succeed is to start with a manageable objective and build on the basis of demonstrable capability. Add commitment, chemistry and patient satisfaction and success will follow.

Table 2.

Could I, should I, start a network? Questions to answer

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What is a critical mass of relevant patients? | Enough to populate a clinic every 3–4 months |

| Will my patients benefit from a local arrangement? | Requirement to proceed |

| Do I want to do more of the work locally? | Requirement to proceed |

| Do I have the time? | Find it |

| Will the hub be interested? | Highly likely |

| Will my local colleagues be interested? | Not essential, initially |

| Will other hospitals get involved? | If yes, a significant strength |

| Will my managers be interested? | Possibly not |

| Could my mangers be obstructive? | Possibly, unless projected efficiency and patient satisfaction appreciated at outset |

| What do I want to achieve? | Map out your ambitions |

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Open Access: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/