Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Right ventricular failure is often the final phase in acute and chronic respiratory failure. We combined right ventricular unloading with extracorporeal oxygenation in a new atrio-atrial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

METHODS

Eleven sheep (65 kg) were cannulated by a 28-Fr inflow cannula to the right atrium and a 25-Fr outflow cannula through the lateral left atrial wall. Both were connected by a serial combination of a microaxial pump (Impella Elect®, Abiomed Europe, Aachen, Germany) and a membrane oxygenator (Novalung®—iLA membrane oxygenator; Novalung GmbH, Hechingen, Germany). In four animals, three subsequent states were evaluated: normal circulation, apneic hypoxia and increased right atrial after load by pulmonary banding. We focused on haemodynamic stability and gas exchange.

RESULTS

All animals reached the end of the study protocol. In the apnoea phase, the decrease in PaO2 (21.4 ± 3.6 mmHg) immediately recovered (179.1 ± 134.8 mmHg) on-device in continuous apnoea. Right heart failure by excessive after load decreased mean arterial pressure (59 ± 29 mmHg) and increased central venous pressure and systolic right ventricular pressure; PaO2 and SvO2 decreased significantly. On assist, mean arterial pressure (103 ± 29 mmHg), central venous pressure and right ventricular pressure normalized. The SvO2 increased to 89 ± 3% and PaO2 stabilized (129 ± 21 mmHg).

CONCLUSIONS

We demonstrated the efficacy of a miniaturized atrio-atrial ECMO. Right ventricular unloading was achieved, and gas exchange was well taken over by the Novalung. This allows an effective short- to mid-term treatment of cardiopulmonary failure, successfully combining right ventricular and respiratory bridging. The parallel bypass of the right ventricle and lung circulation permits full unloading of both systems as well as gradual weaning. Further pathologies (e.g. ischaemic right heart failure and acute lung injury) will have to be evaluated.

Keywords: Respiratory insufficiency, Right ventricular dysfunction, Membrane oxygenators, Heart-assist devices

INTRODUCTION

Veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (vvECMO) therapy is the treatment of choice in severe hypoxemic respiratory failure, particularly in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nevertheless, vvECMO is commonly associated with several disadvantages. Right ventricular failure (RVF) often represents the final phase of the disease [1], and vvECMO treatment is purely symptomatic and not curative [2]. Another issue is, that despite newly developed double-lumen cannulas, vvECMO presents a short-term treatment with the need for large vascular cannulas. In chronic treatment, ambulation of patients would therefore be hard to achieve. Compared with vv devices, passively perfused arterio-venous systems show a less-effective oxygenation due to their perfusion with partially oxygenated blood [3].

We aimed for a mid- to long-term alternative to extracorporeal gas exchange and orientated on today's possibilities of long-term cardiac-assist systems. This alternative should preferably avoid the above-mentioned disadvantages of common vvECMO. Based on an alternative mode of right ventricular decompression, a newly developed device, which actively shunts and oxygenates blood from the right atrium to the left atrium, was investigated in an ovine model of combined respiratory and RVF. Assessing the feasibility of the effective treatment of AVF and RVF by shunting from the right to left atrium is the topic of the present study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our new approach is a support system that shunts blood directly from the right atrium into the left atrium, thus bypassing the pulmonary circuit while oxygenating the shunted volume. To generate active blood flow, a low-resistance membrane oxygenator was placed in series with a microaxial pump. The assist device should provide time for tissue regeneration both of the right ventricle and the lung. It is intentionally conceived as bridge to recovery. The device was set up and evaluated in an open-chest ovine model [4]. We designed the system with forthcoming potential for an ambulatory application and named it ‘Pulmo Right-Left Assist Device’ (PRLAD).

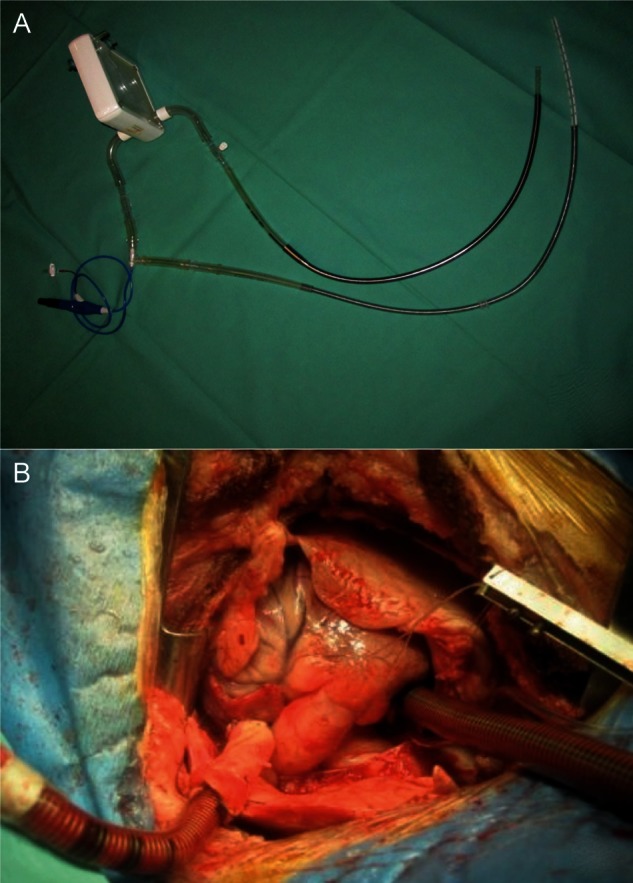

Device set-up

The basic configuration of the system was set up as previously described [4]. Basically, we created an extracorporeal system with an artificial gas-exchange unit combined with an active pump to deliver blood from the right atrium directly to the left atrium. To use the maximum capacity of the pump, we used a ‘low-resistance’ oxygenator (Novalung®—iLA membrane oxygenator; Novalung GmbH, Hechingen, Germany). The Novalung® diffusion membrane has a polymethylpentene surface of 1.3 m2 and is housed in a rather small rigid 15 × 15 cm polyethylene box. It is intended for a blood flow of 0.5–4.5 l/min. The Impella® Elect 600 microaxial pump (Abiomed Europe GmbH, Aachen, Germany) was used to generate active blood flow. This miniaturized rotary blood pump has a diameter of 12 mm, a length of 40 mm and a weight of 6 g. The inner volume of the pump is only 1.5 ml, and the inner artificial and blood contacting surface is 15.9 cm2. At a maximal speed of 33 000 revolutions per minute (rpm), a flow of up to 6 l/min can be generated [5] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1:

Device set-up prior to implantation (A) and in situ position of the cannulas (B).

A 28-Fr cannula (Edwards Lifesciences, USA) was used for the evacuation of the blood out of the right atrium. This cannula was connected via a 3/8″ flexible tube (Raumedic, Helmbrechts, Germany) to the microaxial pump. On the other side of the pump's connector, another 3/8″ tube connected to the gas-exchange unit. Following the gas-exchange unit, a 25-Fr cannula (Bio-Medicus® Femoral Venous Cannula, Medtronic, USA) delivered the oxygenated blood into the left atrium.

Animal model

The animal research protocol was approved by the local authorities (LANUV; Ref. No.: 8.87-51.04.20.09.307). Animals were treated according to the ‘Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals’ published by the US National Institutes of Health (National Institutes of Health Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996).

A total of 11 female Rhoen sheep of 65 (±4) kg were used for this study. Of these, the present apnoea and ventricular failure protocol were performed in four animals.

General preparation

After premedication, anaesthesia was maintained by continuous intravenous application of pentobarbital and fentanyl. Animals were intubated and ventilated. Tidal volumes were adjusted to 8 ml/kg in order to maintain an endtidal PCO2 of 35 mmHg. Oxygen concentration was maintained at 50%. Single-shot antibiotic prophylaxis was administered (Cefuroxime 1.5 g) prior to skin incision. Fluid (Ringers lactate) was given at a rate of 20 ml/kg/h. The temperature of the animal was maintained with a heating blanket and an infrared lamp. During the operation of the oxygenator, the Novalung® was run with 4–6 l/min of oxygen.

Instrumentation and surgical preparations

All animals received a central venous line (Quad-Lumen Indwelling Catheter, Arrow, USA) and a Swan-Ganz catheter (7.5-F, Model VS 1721; Ohmeda, UK) via the left internal jugular vein. A balloon catheter (Arrow-BermanTM Angiography Catheter 6 Fr, 60 cm; Arrow, USA) was inserted into the right ventricle from the right jugular vein to determine right ventricular pressures. An arterial line (18 G, Vygon, Germany) was placed into the left femoral artery under a direct vision.

A small left thoracotomy in the fourth intercostal space was performed. After incising the pericardium, the left atrium was exposed and the pulmonary artery was dissected. A catheter (18 G, Vygon, Germany) was inserted into the left atrium and secured with a suture. All catheters were connected pressure transducers. An ultrasonic flow probe (24 mm, Transonic, USA) was placed around the proximal descending aorta. After complete heparinization, a purse string suture was placed on the free lateral wall of the left atrium.

The 25-Fr outflow cannula was introduced, clamped, sutured and secured to the left atrium after incision of the wall. Thereafter, the 28-Fr inflow cannula was positioned in the right atrium via the right jugular vein under echocardiographic control and also clamped. As a last step, the whole system was carefully deaired and connected to the cannulas.

Acute respiratory failure and right ventricular failure model

Acute respiratory failure (ARF) was modelled by apnoea. To achieve this, the animal was disconnected from the respirator following full relaxation by intravenous administration of 50 mg rocuronium. RVF was induced performing a banding of the very distal main pulmonary artery as previously presented [4]. RVF following pulmonary artery banding was defined as a profound decrease in systemic blood pressure (mean arterial pressure, (MAP) <2/3 of baseline) and depressed cardiac output (cardiac output (CO) <2/3 of baseline). Additionally, right ventricular function was judged by visual inspection.

Experimental protocol

After surgical preparations and connection of the clamped system, a baseline measurement was performed prior to the induction of ARF (time point: Baseline 1).

This was followed by an untreated apnoea. After 5 min (time point: apnoea), the PRLAD was started. After 30 min (time point: apnoea + PRLAD) runtime, the animal was reventilated and the system was turned off for 30 min. Following this recovery period (time point: Baseline 2), ARF and RVF were induced simultaneously by apnoea and pulmonary artery banding. The PRLAD device remained clamped for 3 min (time point: apnoea + banding). Then, the system was started and evaluated after another 30-min period (time point: apnoea + banding + PRLAD).

At the end of the protocol, animals were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital and fentanyl. A macroscopic autopsy of the entire carcass was carried out with focus on the heart, lungs and kidneys.

Data collection and statistics

Data were collected using a certified patient-monitoring system (Datex AS-3 Compact Monitor; Datex Engstrom, USA) and digitally recorded during the study. Flow measurements were also collected and digitally recorded during the study. Blood gas analyses were performed (Radiometer ABL-700, Radiometer Medical ApS, Brønshøj, Denmark). All data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Statistical analyses were performed with a commercially available software (SPSS 20, IBM, USA). Following a Shapiro–Wilk test on the normal distribution of sample differences in our subgroups, analysis of variance was used, followed by a post hoc analysis using the Bonferroni post hoc test. All statistical analyses were performed to a level of significance of 0.05. Statistical testing was performed for the following variables: PaO2, PaCO2, MAP, heart rate (HR), CO and systolic right ventricular pressure (RVP), and post hoc comparison was performed between all interventions (time points).

RESULTS

All animals survived the whole experiment. Surgical preparations were uneventful. The placement of the cannula from the jugular vein into the right atrium was uncomplicated under echocardiographic guidance. The insertion of the left atrial cannula via the lateral thoracotomy also proved to be easy and safe. Neither did catecholamine's have to be administered in any experiment nor did relevant arrhythmia occur.

The PRLAD was easily manageable, and operation of the device was completely without dysfunction. The aimed flow of 4 l/min could be delivered at pump speeds of 33 000 rpm.

Haemodynamics

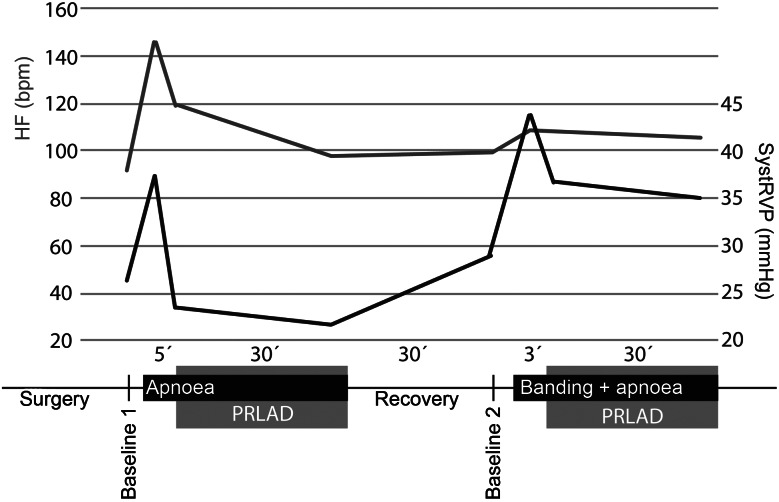

At Baseline 1, measurements showed MAP, heart rate and right ventricular pressure to be in a normal physiological range (Figs 2 and 3). During apnoea, mean arterial pressure rose to 160 ± 49/95 ± 20 mmHg and heart rate, to 162 ± 66 bpm. After starting the PRLAD, MAP and HR normalized quickly and the elevated systolic RVP decreased from 38 ± 7 (time point: apnoea) to 22 ± 10 mmHg (time point: apnoea + PRLAD).

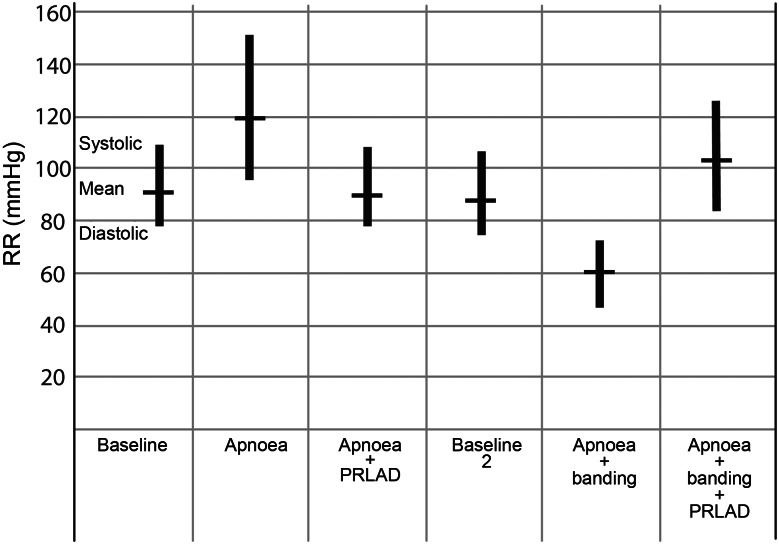

Figure 2:

Haemodynamics and study protocol: the grey line represents the systolic right ventricular pressure (systRVP) and the black line represents the heart frequency (HF). All data present the mean values of four animals, error bars were omitted for better legibility.

Figure 3:

Black columns represent the measured blood pressure (systolic, diastolic and mean arterial pressure).

After stopping the assist device, we detected arterial pressures, heart rate and systolic RVP comparable with the Baseline 1 measurements.

The recovery phase was followed by combined apnoea and pulmonary banding, inducing ARF and concomitant RVF. We saw a significant decrease of CO from 4 ± 0.2 to 0.9 ± 0.4 l/min (P < 0.001) and a decrease in MAP from 88 ± 36 to 59 ± 29 mmHg (n.s.). After starting the PRLAD, the MAD elevated to 103 ± 29 mmHg, and the heart rate stayed at a level of about 100/min. Systolic RVP dropped to 35 ± 3 mmHg.

Altogether, haemodynamics during PRLAD treatment stayed stable. Both during apnoea alone and apnoea combined with pulmonary artery banding, cardiac output remained comparable with baseline values when the PRLAD system was in use.

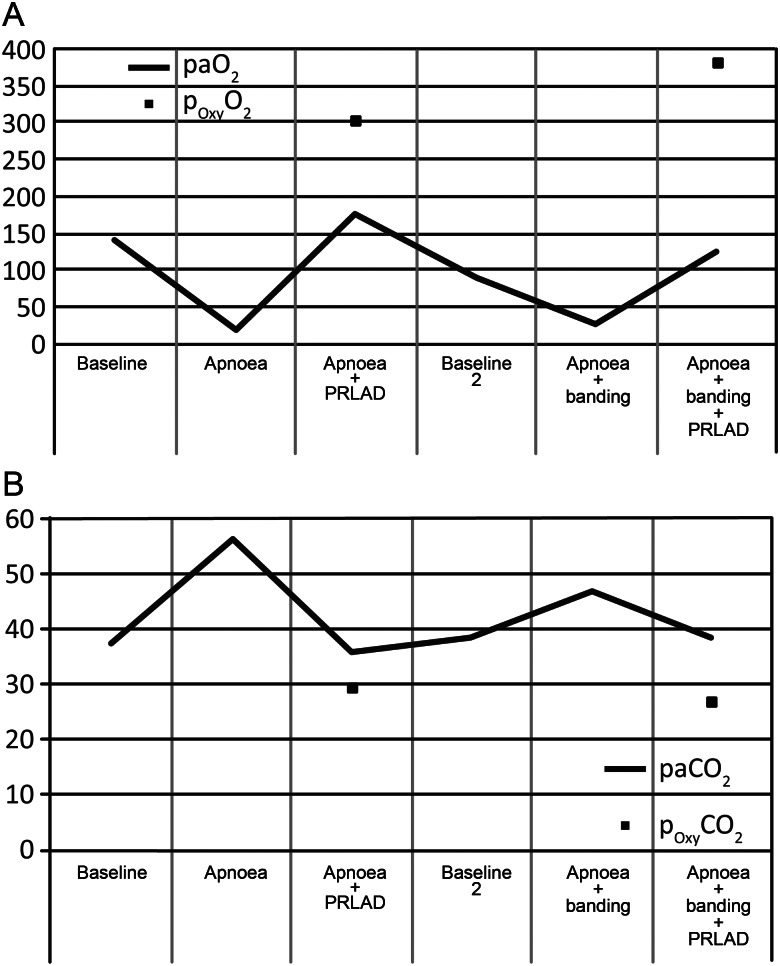

Blood gas analysis

During the apnoea phase, the PO2 dropped significantly from 143.5 ± 59.4 mmHg at Baseline 1 to 21.4 ± 3.6 mmHg (P < 0.01, Fig. 4A). The PO2 increased to 179.1 ± 134.8 mmHg (n.s.) immediately after starting the PRLAD. The interventional lung assist (iLA) provided a PO2 of 303.8 ± 101.5 mmHg directly behind the gas-exchange unit. The decarboxylation during the operation of PRLAD was excellent (Fig. 4B). There was a significant elevation of PCO2 during apnoea and also a significant decrease of PCO2 after starting the PRLAD again (37.5 ± 1.2, 56.3 ± 5.9, 35.7 ± 10.0 mmHg, respectively, P < 0.05 for baseline vs apnoea and apnoea vs apnoea + PRLAD).

Figure 4:

PaO2 (A) and PaCO2 (B) of femoral blood samples in comparison with samples drawn directly behind the oxygenator time points of sampling in accordance to Fig. 2 and the protocol described in the Materials and Methods section. Blood samples from the oxygenator were only taken at phases where the device was in use.

After Baseline 2, the arterial PO2 dropped from 93.5 ± 17.7 to 29.6 ± 11.0 mmHg (P < 0.01) following the induction of ARF and RVF. There was an effective improvement in oxygenation after starting the PRLAD again. An efficient elimination of carbon dioxide was measured. The PCO2 during running PRLAD was in a range (38.8 ± 4.1 mmHg) similar to both baseline values (37.5 ± 1.2 and 38.3 ± 3.4 mmHg).

DISCUSSION

Currently, the status of an ARF with consecutive RVF shows a poor prognosis for the patient [6]. If mechanical ventilation and intensive care management alone fail to provide adequate perfusion and sufficient gas exchange, extracorporeal life support systems are recommendable [7]. Despite recent improvements in veno-venous ECMO therapy and technology, the outcome for patients suffering a combination of ARF and RVF remains unsatisfying. The rate of complications remains high: bleeding complications, thrombo-embolic events, neurological events, capillary leak syndromes, vessels stenosis and injury are frequently encountered [8]. In pure respiratory failure, passively driven interventional lung assist systems offer acceptable oxygenation and good decarboxylation via low-resistance devices. As these systems require a sufficient cardiac output as driving force, their use is limited in concomitant ventricular failure.

Central veno-arterial ECMO is currently the standard therapy in failing the left or right myocardium. It avoids or delays irreversible myocardial damage with subsequent multiorgan failure and death. Its target is either weaning of the device following myocardial recovery or bridging to the implantation of a permanent assist system. In comparison with a veno-arterial ECMO implanted via the femoral vessels, central ECMO provides a safer oxygenation of the supra-aortic vessels and might lead to a higher degree of protection to the brain [9] and a better coronary perfusion.

Compared with central ECMO, our atrio-atrial approach shows distinct advantages: the right ventricle is completely unloaded by our device, and the right ventricular afterload loses its threat. The subsequent augmented filling of the left atrium provides a better left ventricular filling. Contrarily to central EMO, left ventricular afterload is not elevated on PRLAD and a reduced left ventricular function is not forced to work against a central ECMO.

Other approaches such as the veno-venous ECMO maintained via the Avalon Elite® bicaval dual lumen cannula [10, 11] provide sound oxygenation, but do not unload the failing right ventricle. Our approach relieves the right ventricle of any work: the severely elevated right ventricular afterload that is due to the elevated pulmonary resistance does not affect the completely unloaded ventricle.

The unique positioning of our device as a bypass to the lung circulation offers the benefit of addressing haemodynamic and ventilation disorders at the same time. As we already know from our previous investigations, our assist device is capable of sufficient ventricular unloading in RVF. As we now know, it is also capable of providing sufficient oxygenation and decarboxylation in concomitant lung failure.

The key question is whether this unloading contributes to right ventricular recovery in the long term.

In this case, the intended shunting of the lung circulation with a rotary blood pump would additionally allow a stepwise weaning by pump speed reduction in terms of a bridge-to-recovery strategy.

At the moment, we are working on the construction of an implantable transcutaneous trans-atrio septal two-stage cannula. Whereas the anatomical structural conditions complicate the trans-septal approach in the animal model, this should be easier in man. The planned approach of a transcutaneous cannulation with a two-stage cannula that is placed via the transitorily septum avoids sternotomy (or the reopening of previous sternotomy). The remaining atrial septal defect could be closed by commercially available occlude systems.

LIMITATIONS AND PERSPECTIVE

Our experiences with PRLAD are limited to the acute setting. Although in a part of our experiments the device performed soundly for several hours, chronic evaluations will have to follow to further evaluate the circulatory consequences of a voluntary high-degree shunt to the lung perfusion.

Also, for this novel indication, the effectiveness and long-term stability of low-resistance oxygenators will have to be evaluated in long-term series.

CONCLUSION

Our previous and current experiments demonstrated that the use of the pulmonary right-to-left assist device provides sufficient perfusion pressures as well as adequate oxygenation and decarboxylation. The system represents a feasible technique without relevant side effects in the acute setting. Operation of the system without RVF does not lead to significant circulatory changes, whereas it is extremely effective in restoring normal haemodynamics in acute RVF.

Long-term studies and a direct comparison with the ECMO system are necessary to evaluate this type of pulmonary support. In conclusion, the innovative concept of shunting from the right to left atrium by combining a small microaxial pump with an iLA might be beneficial in acute respiratory and RVF and improve weaning capabilities.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant of the START Fund of the RWTH Aachen University.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The pumps were provided by ABIOMED Europe and the oxygenators by Novalung.

APPENDIX. CONFERENCE DISCUSSION

Dr D. Mercogliano (Alessandria, Italy): If you wanted to demonstrate this as a working system, you have succeeded, because it is very easy. I think in the future it may be used for only lung failure, pulmonary resistance failure, but for an assist device for right ventricular failure I have some doubt. You have demonstrated it would work, but in the long-term or the mid-term, 12 hours or 40 hours, maybe when you are start weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass after cardiac surgery, isolated right ventricular failure is very, very rare.

So I have two questions. The first is, during the period of the assist device, how you managed the lung. Did the lung work in the respiratory system? Is it inflated or deflated with the pump? The second question is, when you are weaning from the assist device, do you measure also the pulmonary resistance or only the pressure?

Dr Haushofer: We disconnect the sheep from the respirator, that was our model in those four cases, and we do the normal studies where we have a long-term investigation in the acute setting for six to 12 h and measure also the haemodynamic situation. Concerning your second question, we measure only the pressure. We have severe pulmonary banding; it is about two-thirds of the pulmonary artery.

Dr A. Rastan (Rotenberg, Germany): What is the idea of making the additional pulmonary banding?

Dr Haushofer: To simulate the high pulmonary resistance.

Dr Rastan: To simulate right heart failure?

Dr Haushofer: The right heart failure model without destroying any lung structure.

Dr Rastan: You mentioned the cannulation site to be on the left atrium through a mini-thoracotomy, but as far as I saw on the echo, you made it trans-septally.

Dr Haushofer: It is also open, but transatrially. The aim will be to create a double-lumen cannula for a transcutaneous, trans-septal setting, yes.

Dr Rastan: Are you working on this kind of cannula?

Dr Haushofer: Yes. It is a little bit handmade still, but we try.

Dr Rastan: And you just mentioned some kind of longer-term results?

Dr Haushofer: That will be our next step. The longest time was 12 hours.

Dr Rastan: Over the time it worked with the Novalung?

Dr Haushofer: Yes. There is no problem with the Novalung.

REFERENCES

- 1.Combes A, Bacchetta M, Brodie D, Müller T, Pellegrino V. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure in adults. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18:99–104. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834ef412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haddad F, Couture P, Tousignant C, Denault AY. The right ventricle in cardiac surgery, a perioperative perspective: II. Pathophysiology, clinical importance, and management. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:422–33. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818d8b92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kopp R, Dembinski R, Kuhlen R. Role of extracorporeal lung assist in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Minerva Anestesiol. 2006;72:587–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spillner J, Stoppe C, Hatam N, Amerini A, Menon A, Nix C, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of bypassing the right ventricle and pulmonary circulation to treat right ventricular failure: an experimental study. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christiansen S, Dohmen G, Autschbach R. Treatment of right heart failure with a new microaxial blood pump. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2006;14:418–21. doi: 10.1177/021849230601400515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price LC, McAuley DF, Marino PS, Finney SJ, Griffiths MJ, Wort SJ. Pathophysiology of pulmonary hypertension in acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L803–15. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00355.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peek GJ, Elbourne D, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, Wilson A, Allen E, et al. Randomised controlled trial and parallel economic evaluation of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR) Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1–46. doi: 10.3310/hta14350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalwin RP, Moran JL, Graham PL. The role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for treatment of the adult respiratory distress syndrome: review and quantitative analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2008;36:152–61. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0803600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mateen FJ, Muralidharan R, Shinohara RT, Parisi JE, Schears GJ, Wijdicks EFM. Neurological injury in adults treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1543–9. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiu F, Lu CK, Palanzo D, Baer LD, Myers JL, Undar A. Hemodynamic evaluation of the Avalon Elite bi-caval dual lumen cannulae. Artif Organs. 2011;35:1048–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2011.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou X, Wang D, Sumpter R, Pattison G, Ballard-Croft C, Zwischenberger JB. Long-term support with an ambulatory percutaneous paracorporeal artificial lung. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:648–54. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]