Abstract

The disease caused by the apicomplexan protozoan parasite Theileria parva, known as East Coast fever or Corridor disease, is one of the most serious cattle diseases in Eastern, Central, and Southern Africa. We performed whole-genome sequencing of nine T. parva strains, including one of the vaccine strains (Kiambu 5), field isolates from Zambia, Uganda, Tanzania, or Rwanda, and two buffalo-derived strains. Comparison with the reference Muguga genome sequence revealed 34 814–121 545 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were more abundant in buffalo-derived strains. High-resolution phylogenetic trees were constructed with selected informative SNPs that allowed the investigation of possible complex recombination events among ancestors of the extant strains. We further analysed the dN/dS ratio (non-synonymous substitutions per non-synonymous site divided by synonymous substitutions per synonymous site) for 4011 coding genes to estimate potential selective pressure. Genes under possible positive selection were identified that may, in turn, assist in the identification of immunogenic proteins or vaccine candidates. This study elucidated the phylogeny of T. parva strains based on genome-wide SNPs analysis with prediction of possible past recombination events, providing insight into the migration, diversification, and evolution of this parasite species in the African continent.

Keywords: Theileria parva, genome sequence, SNPs, recombination, dN/dS

1. Introduction

Theileria parva is a tick-borne protozoan parasite belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa. Infection of T. parva in cattle causes a severe disease known as East Coast fever (ECF) or Corridor disease.1–3 The disease is endemic in East African countries, where it has caused a serious economical problem to the livestock industry. Although the mortality in cattle may reach 100%, especially in exotic breeds, the Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer) shows no clinical signs and is considered to be the main natural host. Although clinical differences have been documented,4 ECF and Corridor disease have similar presentations. However, a major epidemiological difference is that, whereas ECF spreads from cattle to cattle, Corridor disease is believed to be transmitted solely from buffalo to cattle. The parasites causing ECF and Corridor disease were designated as T. p. parva and T. p. lawrencei, respectively.3

Vaccination against ECF is based on an infection and treatment method that involves inoculation of live sporozoite-stage parasites and simultaneous treatment with long-acting tetracycline.5 The Muguga cocktail, consisting of the three strains of Muguga, Serengeti-transformed, and Kiambu 5, is the most widely used vaccine in East Africa. Importantly, there is an extensive debate concerning the risk of vaccination with live non-attenuated sporozoites such as the Muguga cocktail vaccine, as the vaccination may introduce parasites with an exotic genetic background into the local parasite population.6–9 This was proven to be a real risk when Oura et al.7 demonstrated the transmission of a strain of vaccine constituent to unvaccinated cattle under field conditions in Uganda. In addition, the presence of the vaccine component strain (Muguga or Serengeti-transformed) was confirmed in clinical cases of ECF in the Southern Province of Zambia,6 following deployment of the Muguga Cocktail over a 7-year period, ranging from 1986 to 1992. Therefore, two indigenous Zambian strains (Katete and Chitongo) have been used as a vaccine in the Eastern and Southern Provinces of Zambia,10 although the consequences of this vaccination have not been analysed.

Given that Theileria parasites could recombine between divergent strains during the sexual stage in ticks, vaccine-derived ‘exotic’ and ‘local’ strains could exchange genetic information, resulting in parasites with genetic mosaics and diversity. In addition to the problems with the current vaccine, quality control of the cocktail vaccine in terms of the composition of each component is difficult. This may be related to recombination and selection during the maintenance and passage of the stabilates through ticks.11 Thus, precise and reliable methods for parasite genotyping or phenotyping during vaccine production and its field application are required.

Genetic diversity between different T. parva strains has been assessed using various approaches, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) of polymorphic antigen-encoding genes,6,12 or the indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) using monoclonal antibodies against the surface protein, the polymorphic immunodominant molecule (PIM).13 A panel of micro- and mini-satellite markers has also been developed14,15 that is widely used in the genetic analysis of field populations7,8 and has also been used to characterize vaccine stabilates11 and genetic recombination analysis.16–18 However, the resolution of genetic differentiation in these studies is limited because of the relatively low marker density.

In this study, we carried out the whole-genome sequencing of nine T. parva strains, comprising seven cattle-derived and two buffalo-derived strains, using next-generation sequencing technology. Genome-wide comparison of strains revealed genetic polymorphisms on a fine scale and was used to infer phylogenetic relationships among the parasites. The analysis enabled us to determine potential immune selective pressures against parasite genes, which may prove useful in identifying potential antigens. Moreover, the allelic diversity pattern among strains gave us insight into the evolution, diversification, and migration of this parasite in the African continent.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Parasite strains

In total, nine strains of T. parva, mainly isolated in the 1980s, were used in this study. The place and the year isolated are shown in Table 1. These strains were originally isolated in ticks from infected cows and cultured as schizont-infected bovine lymphocyte cell lines. ChitongoZ2and KateteB2 have been used as sporozoite stabilate vaccines in the Eastern and Southern Provinces of Zambia.10 Kiambu 519 is one of the Muguga cocktail vaccine components, and KiambuZ464/C12 is a strain that has been cloned out from Kiambu 5 (Kenya, stabilate 68). Zambian strains KateteB2, ChitongoZ2, and MandaliZ22H10 were isolated before the introduction of the Muguga cocktail into Zambia, thus representing ECF epidemiology in Zambia, excluding human-induced genetic contamination. In addition, the analysis included two buffalo-derived isolates, LAWR and Z5E5. Z5E5 is a buffalo-type isolate obtained from a bovine, whereas LAWR is a buffalo-type isolate obtained from a buffalo. KiambuZ464/C12, MandaliZ22H10, and Z5E5 were cloned by limiting dilution. These Theileria-infected cell lines did not undergo extensive passages (<30 passage) and were stored in liquid nitrogen until use. Cultures were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) -1640 culture medium containing 10 or 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 mg/ml streptomycin.

Table 1.

T. parva strains sequenced in this study with the summary of Solexa sequence results

| Strain name | Place isolated | Isolated year | Total reads obtained | Reference genome mapped reads | Mapped read (%) | Average coverage | Genome covered (%) | SNP number |

SNP density (per 1kb) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Coding | Non-coding | Overall | Coding | Non-coding | ||||||||

| ChitongoZ2 | Zambia | 1982 | 14 405 285 | 11 225 629 | 77.9 | 49.1 | 97.4 | 46 366 | 31 753 | 14 613 | 5.63 | 5.48 | 5.99 |

| KateteB2 | Zambia | 1989 | 16 558 765 | 4 954 291 | 29.9 | 21.3 | 97.3 | 43 873 | 31 533 | 12 340 | 5.33 | 5.44 | 5.06 |

| Kiambu Z464/C12 | Kenya | 1972 | 15 848 447 | 6 278 932 | 39.6 | 27.4 | 97.2 | 46 435 | 33 021 | 13 414 | 5.64 | 5.70 | 5.50 |

| MandaliZ22H10 | Zambia | 1985 | 16 362 287 | 3 904 897 | 23.9 | 17.1 | 97 | 38 498 | 28 270 | 10 228 | 4.67 | 4.88 | 4.19 |

| Entebbe | Uganda | 1980 | 10 171 312 | 3 547 208 | 34.9 | 15.5 | 95.2 | 34 814 | 27 195 | 7619 | 4.23 | 4.69 | 3.12 |

| Nyakizu | Rwanda | 1979 | 29 366 782 | 5 710 634 | 19.4 | 25 | 97 | 51 790 | 34 700 | 17 090 | 6.29 | 5.99 | 7.01 |

| Katumba | Tanzania | 1981 | 35 406 725 | 4 089 736 | 11.6 | 17.9 | 97.1 | 46 441 | 32 321 | 14 120 | 5.64 | 5.58 | 5.79 |

| Buffalo LAWR | Kenya | 1990 | 17 072 360 | 6 155 888 | 36.1 | 26.9 | 94.7 | 121 545 | 77 472 | 44 073 | 14.76 | 13.37 | 18.07 |

| Buffalo Z5E5 | Zambia | 1982 | 14 821 054 | 5 119 542 | 34.5 | 22.4 | 95.3 | 103 880 | 68 454 | 35 426 | 12.61 | 11.81 | 14.52 |

2.2. Parasite purification and genomic DNA preparation

Schizont-enriched material was prepared from the infected lymphocytes by a density-gradient separation method as previously described,20–22 with some modifications. The cells were treated with 3 µM nocodazole for 18 h, and then harvested cells were lyzed for 30–60 min at room temperature with a Gram-negative bacterium, Aeromonas hydrophila (AH-1)-derived haemolysin, in a suspension of HEPES-CaCl2 (10 mM-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, and 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) to obtain a cell concentration of 4 × 107 cells/ml (0.5–2 × 108 cells in total). Crude AH-1 haemolysin was prepared by bacterial culture supernatant according to a previously described method23 and was added to the cell suspension at a final concentration of 100 U/ml. Lysis of infected lymphocytes was observed under a microscope. If complete cell lysis was not observed after 15 min, then the incubation period was prolonged until almost 100% of cells were lyzed, whereas schizonts remained intact. Because the sensitivity of schizont-infected cells varied significantly between cell lines, the maximum incubation time was 120 min. After lysis, the suspension was washed with HEPES-CaCl2 and re-suspended in 3 ml of HEPES-ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, and 5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4). Four layers of Percoll solution comprising 10, 10, 5, and 5 ml of 65, 40, 30, and 20% Percoll in HEPES-EDTA, respectively, were prepared in an ultracentrifuge tube. The cell lysate was overlaid on top of the Percoll solution and ultracentrifuged at 87 000 g for 30 min at 4°C, using a SW41 rotor (Beckman, USA). The schizont layer that formed at the interface between 40 and 65% Percoll solutions was carefully collected with a Pasteur pipette and then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove the Percoll. A sample of each schizont preparation was stained with Giemsa, and preparations with negligible amounts of contamination with host-cell components were subjected to DNA isolation.

2.3. DNA preparation, whole-genome amplification, and Illumina genome analyzer II (GAII) sequencing

Genomic DNA was prepared from the purified schizonts using the NucleoSpin Tissue XS protocol (Machery-Nagel, Duren, Germany). Whole-genome amplification was performed on 10 ng of the total template DNA using an Illustra GenomiPhi V2 DNA Amplification Kit (GE Healthcare) following the manufacturer's instructions.24,25 The obtained DNA was purified by ethanol precipitation and subjected to sequence analysis. A 36 nucleotide, single-end sequence run was performed on the Illumina GAII Analyzer following the manufacturer's protocols (Illumina, San Diego, GA, USA).

The obtained reads, as listed in Table 1, were mapped on the 8 235 476 bp sequence of the T. parva Muguga strain (AAGK01000001, AAGK01000002, AAGK01000005, AAGK01000006, and AAGK01000004) using the CLC Genomics Workbench (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark, Version 4.0.2). The ungapped alignment algorithm was used for all alignments, keeping the default parameters for mismatch and deletion costs (mismatch cost = 2, deletion cost = 1). Files containing these short sequence reads were submitted to the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive (accession number DRA000613).

2.4. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) analysis

Three sets of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were defined (Supplementary Fig. S1). SNPs were identified by comparing each re-sequenced genome with the reference Muguga strain.26 SNP detection was performed using the SNP detection tool in the CLC Genomic Workbench with the default parameters (window length = 11, maximum number of gaps and mismatch = 2, minimum average quality surrounding bases = 15, and minimum quality of central base = 20),27 except for the minimum coverage that was set at five reads, and the list was manually curated to include only SNPs, where all reads within a single sample agreed (SNP dataset I). The extracted SNPs data were exported and analysed by Microsoft Office Excel 2010. SNP dataset I was used for creating a SNPs density map and for dN/dS analysis. From SNP dataset I, SNPs identified among the eight bovine T. parva strains were extracted. To avoid calling block substitutions as SNPs, SNPs were only selected, if they did not exist within 100 bp of another SNP, and this provided SNP dataset II. Allelic data from each strain were extracted, and this information was used for the allelic combination and recombination analysis. SNP dataset III was created using the eight cattle-derived and two buffalo-derived strains, and again SNP positions were required to have at least 100 bp intervals. Thus, the high stringency dataset encompassing all 10 Theileria strains (including the reference strain), SNP dataset III, was used for phylogenetic analysis. Plots of the allele combination pattern for each chromosome were generated using freeware and open-source R software version 2.11.1 (R Development Core Team, 2010; http://www.R-project.org). Genes under selection pressure were estimated by calculating the dN/dS between strains with the SNP dataset I by the method of Yang et al.,28 implemented in the PAML package.29 Signal sequences for all the annotated genes of the Muguga strain were predicted using SignalP v4.0.30

2.5. Phylogenetic tree and recombination detection

To identify the relationship between the sequences of the nine strains and the Muguga reference strain, an unrooted neighbour-net tree31 was constructed based on the concatenated SNP dataset III using Split tree version 4.11.3.32 The Recombination Detection Program version 3.44 (RDP3) was used to detect possible recombination regions.33 This software incorporates several recombination prediction methods. As the reliability of each method has not been fully evaluated, it is anticipated that some of the recombination events predicted may be artifactual. We manually curated the results choosing Geneconv34 and maximum Chi-square35 as the selection priority, as the accuracy of these tests is relatively well defined.36 Predicted recombination events were considered valid, if at least one additional program supported the findings, i.e. (P ≤ 0.001) for that event from RDP,37 Boot scanning,38 3 Seq method,39 or the sister-scanning method.40 Predictions that did not meet these criteria were removed. For phylogenetic analysis of p150 and p104, we used mapping sequence information for each strain, and unmapped or unreliable regions were filled by manual Sanger sequencing. The sequences obtained in this study were submitted to GenBank under accession no. AB739676–AB739693.

3. Results

3.1. Genome sequencing of nine T. parva strains using Illumina technology

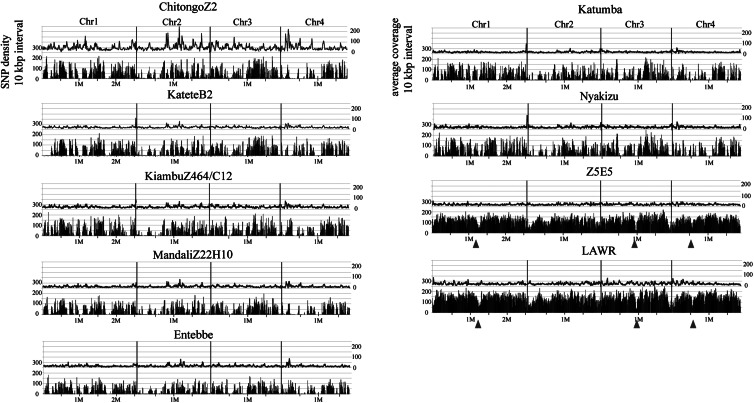

Single runs of Illumina produced over 10 million reads for each sample, and this provided coverage of 94.7–97.5% for genomes of individual strains against 8.3 M of the reference Muguga genome, with an average coverage between ×17 and ×49 (Table 1). Depending on the purity of the preparations, 11.6–77.9% of the total reads for any one strain were successfully mapped, whereas unmapped reads were considered to be derived from host genomic DNA. All four chromosomes of each stock were evenly covered in general, except for ChitongoZ2 (Fig. 1). As the concentration of extracted DNA from purified schizonts in ChitongoZ2 strain was lowest, we suspect that the whole-genome amplification procedure for this strain caused biased amplification, resulting in an uneven distribution of the coverage; however, this did not affect SNPs detection.

Figure 1.

SNPs distribution across the Theileria genome. SNPs in individual strains were detected after mapping to the reference genome Muguga strain. The entire datasets of 34 814–121 545 SNPs (SNP dataset I) were plotted as SNP densities (per 10 kb intervals) alongside chromosome 1–4. The x-axis shows the chromosomal position, and the left y-axis shows the number of SNPs (black bars) per 10 kb interval. Average short read coverage is also shown on the right y-axis (above line). Arrowheads indicate the possible location of the centromere.

3.2. SNPs detection

Stringent conditions for SNPs detection were used, i.e. more than five high-quality reads covering the SNPs and 100% concordance in position. If multiple allele variants calling was allowed, 5216 loci had complex SNPs in at least one strain (0.0633% of the reference Muguga genome). As the genome of Theileria at the schizont stage is haploid, only a single allele is expected at each locus, and complex SNPs are unexpected, if the sample contains a clonal population. The appearance of these multi-allelic SNPs could represent base-calling or mapping errors (due to repetitive sequence or paralogous genes). Because other possibilities that these SNPs were generated during in vitro passages after cloning by the limited dilution and that minor populations in the original materials obtained from host animals remained in the analysed samples cannot be excluded, such questionable SNPs were excluded in further analysis. Although it is likely that some genuine SNPs may be overlooked, a high stringency SNPs calling protocol was utilized to avoid false SNPs calls.

The number of SNPs identified in bovine-derived strains when compared with the Muguga strain ranged from 34 814 in the Entebbe strain to 51 790 in the Nyakizu strain. Additionally, 121 545 and 103 880 SNPs were identified in buffalo-derived LAWR and Z5E5 strains, respectively (Table 1). The densities of the SNPs in each chromosome tended to be higher in chromosomes 1 and 3 than in chromosomes 2 and 4 in most of the strains (Fig. 2). Out of a total of 533 642 SNPs identified in 9 strains (Table 1), 364 719 were present in coding regions (cSNP) and 168 923 were present in non-coding regions (ncSNP), although the SNP density (calculated per 1 kp) of cSNPs and ncSNPs were similar (Table 1). The numbers of SNPs ranged from 34 814 (Entebbe) to 121 545 for the buffalo-derived LAWR strain, and more than 2-fold SNPs were identified in 2 of the buffalo-derived strains when compared with the cattle-derived strains (Table 1), suggesting a degree of genetic differentiation between these types of Theileria. As shown in Fig. 1, clustered distribution of SNPs was observed (black bars in each panel). The uneven distribution of SNPs was not found to correlate with the sequence coverage distribution (line); thus, the effect of low SNPs calling efficiency in particular regions can be excluded. In addition, lower SNPs densities were observed within defined regions on chromosomes 1, 3, and 4, which was most evident in buffalo-derived Theileria strains (Fig. 1, arrowhead). These regions correspond to the putative centromeres with an extremely AT-rich composition.

Figure 2.

SNP density in each chromosome (SNP dataset I). Average SNP densities per 1 kb interval were calculated for each chromosome in nine T. parva strains with reference to the Muguga genome strain. In the published full genome sequence of T. parva, there is a large gap in the assembly of chromosome 3, due to the repetitive Tpr locus. The large contig AAGK01000005 and smaller contig AAGK 01000006 are shown as Chr3_530 and Chr3_531, respectively.

3.3. dN/dS analysis

The ratio of the number of non-synonymous substitutions per non-synonymous site (dN) to synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS) both at the inter- and intra-species level has been used to estimate the potential selective pressure acting on the genes.41 A dN/dS ratio lower than one suggests negative or purifying selection, whereas a ratio higher than one suggests positive selection or diversification. Estimation of dN/dS ratios can potentially identify genes encoding immunogenic proteins and, thus, putative vaccine candidates.42 Therefore, we calculated dN/dS ratios for individual genes using SNP dataset I for seven bovine Theileria strains with the yn00 program of the PAML package.29 Overall, the dN/dS ratios calculated between cattle T. parva strains were average values of 0.0894–0.0993 when pair-wise comparisons were performed against the Muguga strain, with similar values to those observed in the comparison between T. parva versus Theileria annulata (average dN/dS = 0.097).43 Among a total of 4011 genes annotated on the Muguga genome, 263 genes showed elevated levels of dN/dS values (average + 3SD) in at least 1 strain (Supplementary Table S1). We further narrowed the list down to 71 genes by selecting only those genes that have a signal sequence for targeting to the endoplasmic reticulum. Those selected genes may be potential targets of the host's immune system. The final list of these possible antigenic, and therefore vaccine target, genes is shown in Table 2, and the orthologous groups were also assigned according to our previous study.44 Most of the other genes listed here are currently annotated as hypothetical proteins without any predicted functional domain. However, some of them are known to be recognized by host humoral immunity. For example, p32 (TP01_1056)45 and 23 kDa piroplasm surface protein (TP02_0551)46 are erythrocytic piroplasm stage antigens, and strong antibody response in infected cattle has been reported.

Table 2.

List of genes with high dN/dS ratios and a secretion signal peptide 71 genes were listed from 263 genes (higher dN/dS ratios), by selecting secretion signal peptide-predicted genes

| GeneID | Description | Ortholog group | Signal | GeneID | Description | Ortholog group | Signal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP01_0144 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0002444 | Y | TP03_0003 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y |

| TP01_0178 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0002919 | Y | TP03_0039 | Hypothetical protein | Not assigned | Y |

| TP01_0180 | 40S ribosomal protein S11 | PiroF0000589 | Y | TP03_0040 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0003613 | Y |

| TP01_0291 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0002390 | Y | TP03_0123 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0002851 | Y |

| TP01_0367 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0000012 | Y | TP03_0217 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0000012 | Y |

| TP01_0378 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0003402 | Y | TP03_0297 | Hypothetical (FAINT superfamily) | PiroF0100056 | Y |

| TP01_0380 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0003404 | Y | TP03_0298 | Hypothetical (FAINT superfamily) | PiroF0000056 | Y |

| TP01_0610 | Hypothetical (Tash family) | PiroF0100038 | Y | TP03_0319 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0000012 | Y |

| TP01_0619 | Hypothetical (Tash family) | PiroF0100038 | Y | TP03_0368 | Hypothetical (FAINT superfamily) | PiroF0100056 | Y |

| TP01_0621 | Hypothetical (Tash family) | PiroF0100038 | Y | TP03_0405 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0002425 | Y |

| TP01_0914 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0002316 | Y | TP03_0498 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y |

| TP01_0955 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0003569 | Y | TP03_0520 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0000012 | Y |

| TP01_0987 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0002967 | Y | TP03_0530 | Hypothetical protein | Y | |

| TP01_1011 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0100045 | Y | TP03_0664 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0000012 | Y |

| TP01_1044 | Hypothetical protein | Not assigned | Y | TP03_0780 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0002660 | Y |

| TP01_1056 | 32 kDa surface antigen | PiroF0002963 | Y | TP03_0810 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0002675 | Y |

| TP01_1109 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0000207 | Y | TP03_0886 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y |

| TP01_1227 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y | TP03_0893 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y |

| TP02_0004 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y | TP04_0009 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y |

| TP02_0006 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y | TP04_0012 | Hypothetical (FAINT superfamily) | PiroF0100056 | Y |

| TP02_0010 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y | TP04_0013 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y |

| TP02_0018 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0100055 | Y | TP04_0096 | Hypothetical (FAINT superfamily) | PiroF0100056 | Y |

| TP02_0239 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0002609 | Y | TP04_0097 | Hypothetical (FAINT superfamily) | PiroF0100056 | Y |

| TP02_0327 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0000012 | Y | TP04_0101 | Hypothetical (FAINT superfamily) | PiroF0100056 | Y |

| TP02_0331 | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme, putative | PiroF0002575 | Y | TP04_0104 | Hypothetical (FAINT superfamily) | PiroF0100056 | Y |

| TP02_0551 | 23 kDa piroplasm surface protein | PiroF0003021 | Y | TP04_0110 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0001224 | Y |

| TP02_0575 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0003017 | Y | TP04_0116 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0003546 | Y |

| TP02_0819 | Hypothetical (FAINT superfamily) | PiroF0100056 | Y | TP04_0150 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0000037 | Y |

| TP02_0856 | Hypothetical (FAINT superfamily) | PiroF0100056 | Y | TP04_0328 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0002219 | Y |

| TP02_0875 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0002985 | Y | TP04_0411 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0003185 | Y |

| TP02_0952 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0003456 | Y | TP04_0437 | 104 kDa antigen | PiroF0003088 | Y |

| TP02_0954 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y | TP04_0558 | Hypothetical protein | PiroF0001517 | Y |

| TP02_0956 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y | TP04_0919 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y |

| TP03_0001 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y | TP04_0920 | Hypothetical (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y |

| TP03_0002 | Hypothetical protein (SVSP) | PiroF0100037 | Y | TP04_0921 | Hypothetical protein (FAINT superfamily) | PiroF0000056 | Y |

3.4. Phylogenetic relationship among 10 T. parva strains and evidence of recombination

The allele frequency or combination of the bovine Theileria strain alleles collected in SNP dataset II was determined. By scoring biallelic positions only, 127 allelic combinations were identified among 8 bovine Theileria. Each of the 15 901 SNPs was assigned 1 of the 127 combinations. When the rank order of these combinations was calculated, the allele pattern unique to the Muguga strain came first, followed by Nyakizu-, KiambuZ464/C12-, and Katumba-unique allele combinations (Fig. 3). Because Muguga strains were used as the reference sequence, ranking ‘Muguga strain-unique allele pattern’ as the first event seems reasonable, as it incorporates a minor allele that is present in the Muguga strain. The distribution of frequencies among the 127 events was uneven because 54% of all SNPs were assigned to these top 10 allelic combinations. When the list was extended to cover the top 20 or 25 combinations, this ratio increased to 73 and 80%, respectively, indicating that most of the SNPs alleles were represented by a limited number of combinations. The distribution of these different SNPs patterns is represented on a schematic diagram of the chromosomes, and different combination events are colour coded (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 3, allelic combinations among the strains are distributed throughout every chromosome. A major observation was that SNPs with particular allelic combinations tend to cluster into defined loci, giving rise to a rough, large-scale mosaic pattern of allelic combinations. If the evolution of these strains had taken place completely independently, i.e. without interaction between strains, this clustering of allelic combinations would not be expected.

Figure 3.

Mosaic pattern of SNPs in T. parva strains. The frequency of each of the 127 possible allelic combinations for the 8 cattle-derived T. parva strains was calculated using the SNP dataset II. The 10 top-ranking combinations were plotted onto schematic chromosomes in the assigned colours. Each line within a chromosome represents a single SNP marker position.

The relationships among the 10 T. parva strains were analysed by creating a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4). The allelic combinations are well correlated with the phylogenetic relationship among these strains, and the top 10 allelic combination events represented major nodes in the tree. Neighbour net is a phylogenetic network construction method that combines aspects of the neighbour joining and Split tree. In this neighbour-net analysis, the appearance of the reticulated branches indicates the recombination events. Considered together with the mosaic allelic combination patterns as described above (Fig. 3), we speculate that recombination events are responsible for the interrelationships between strains. To verify this hypothesis, we carried out further recombination event estimations with the RDP programs. The concatenated SNP dataset II was subjected to six recombination detection tests, namely Geneconv, maximum Chi-square, RDP, Boot scanning, 3 Seq., and sister-scanning methods. This resulted in a minimum of 133 recombination events being predicted as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. A snapshot of the alignment of a concatenated version of the SNP dataset II is also shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. An RDP analysis was also carried out using the SNP dataset III, but no significant evidence for recombination was detected between cattle- and buffalo-derived strains (Z5E5 and LAWR, data not shown).

Figure 4.

Neighbour-net network analysis of 10 T. parva strains. Neighbour-net network analysis was performed with the concatenated SNP allele sequence data from SNP dataset III. Bootstrap values are based on 100 replicates and were near 100 at most of the nodes.

As polymorphic antigens such as p104 or p150 have been used for the genotyping of T. parva,6 we compared results of genotyping based on p104 or p150 with those obtained by SNPs analysis. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S4, there was no congruency in tree shapes. The most likely explanation for this inconsistency is that the recombination event between the ancestral strains involved these loci, as is evident in Supplementary Fig. S2. RDP3 program predicts recombination events within those two loci. In p104 loci, KateteB2 and Katumba are predicted to be recombinant from unknown parent or Entebbe strains. And this is true for Muguga, KiambuZ464/C12, and the possible donor, Nyakizu, at the p150 locus as marked in Supplementary Fig. S2.

4. Discussion

Comparison of whole-genome sequencing data of several Theileria strains, using short reads sequencing and mapping on the reference genome sequence, revealed genome-wide nucleotide-based polymorphisms in this species. SNPs density plots evaluate clustered SNPs distribution across the genome and identify SNP-poor and SNP-rich regions. Such a clustering of SNPs has been also reported in mammalian genome, although the forces responsible (e.g. mutation hot spot, recombination, or balancing selection) remain poorly understood.47,48 For apicomplexan parasite, reports for the genome-wide SNPs analysis are limited, but similar SNPs distribution pattern was observed in Plasmodium49 suggesting existence of the same underlying mechanisms between parasite and mammalian genomes for these SNPs clustering.

Our SNPs analysis clarified the phylogenetic relationships among 10 Theileria strains on a genome-wide scale. When these Theileria strains were further analysed using neighbour-net analysis, clusters were formed in accordance with both host species and geographical origin. For example, three Zambian strains (ChitongoZ2, MandaliZ22H10, and KateteB2) were clustered together in the same node, inferring that they are closely related genotypes, but distant from strains isolated in Eastern Africa. In addition, there is a clear demarcation between the bovine- and buffalo-derived strains (Z5E5 and LAWR). Genetic difference between Z5E5 and LAWR was also confirmed as high numbers of SNPs were not shared between Z5E5 and LAWR, as is shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. However, reticulated patterns between strains belonging to different clusters are evident, as shown in Fig. 4, which suggests genetic recombination between ancestors of the strains that are currently geographically separated. The evidence for recombination among the analysed strains was further supported by the presence of a mosaic pattern of allelic combinations, together with the statistical analysis of recombination. This result is intuitive when one considers the fact that the parasite has an obligate sexual cycle and that analysis of field populations suggests that recombination in the tick vector is commonplace.14 There are two possibilities of ticks being infected with parasites with different genotypes: infestation on a single bovine host infected with genotypically mixed parasite populations or multiple infestations on different animals infected with different parasite genotypes that are possible for two or three host tick species. However, the latter is less likely, as synchronization of the sexual stages (micro- and macro gamete) between two parasites is difficult, if they are picked up by ticks at different feeding times.

We hypothesize that genetic recombination occurred in the ancestral bovine Theileria populations in the distant past, and parasites had evolved independently after geographical isolation. The origin of T. p. parva in cattle is unknown, but it is considered likely to have originated in the African buffalo.50 Evidently, T. parva populations in buffalo are considered to be more diverse than in cattle6,13,51 and cause severe disease in cattle. Historically, domestic cattle were believed to have been introduced to the African continent thousands of years ago, possibly into Sub-Saharan Africa from the Mideast.52–54 After the introduction of cattle, a subset of the buffalo Theileria population may have been transmitted (at that stage, it would be called T. p. lawrencei, as it could not infect other cattle), adapted, and co-evolved within cattle, resulting in the emergence of T. p. parva that can spread within cattle.

It should be emphasized that the phylogenetic tree obtained from two polymorphic antigens (p104 and p150) showed a different topology from that based on genome-wide SNPs. Thus, the interpretation of the phylogenetic relationship, analysed by a limited number of loci, must be made carefully in the case of pathogens that acquire genetic diversity by recombination, rather than by accumulation of mutations. This is due to the fact that each locus can become chimaeric by crossing over between genotypes that have different evolutional histories. Therefore, a number of independent loci should be included to estimate the real relationship between isolates such as multi-locus sequencing typing, but genome-wide SNPs analysis is the ultimate solution in this context.

Two buffalo-derived strains (Z5E5 and LAWR) were genetically distant from cattle-derived Theileria strains and between the two strains, as expected from earlier studies.6,13,51 It has been proposed that genetic exchange between buffalo-derived Theileria and cattle-derived Theileria still occurs through sexual recombination, based on evidence that T. p. lawrencei and T. p. parva showed a mosaic sequence pattern in the ITS region.55 However, in our recombination analysis using the RDP program, no recombination events were detected between bovine and buffalo Theileria strains. It might be hypothesized that cattle-infecting strains were originated from a subset of buffalo-infecting T. parva population that has been circulating in Africa for a long time and now have evolved a genetic barrier to recombination. Further analysis with a greater number of buffalo-derived samples and denser SNPs coverage would be needed to clarify the genetic relationship between buffalo and cattle Theileria more precisely.

Estimation of dN/dS values can potentially identify immunogenic genes under possible selective pressure and, thus, possible vaccine candidate molecules. The selected candidate 71 antigen list (Table 2) covers most of the known genes for antigenic or host-interacting proteins, which confirms the effectiveness of this genome-wide approach. p2346 and p3245 are surface or secreted antigens recognized by humoral immunity in infected animals. The diversification of these genes may be related to immune evasion of the Theileria parasite.

On the other hand, although several genes with CTL targets have been identified as being under possible immune pressure,56 only Tp1 (TP03_0849) showed a higher dN/dS value in this study, whereas other genes for CTL targets (Tp2-9) showed relatively low dN/dS values (Supplementary Table S2). Relative conservation of the sequences of these CTL antigen genes among the different parasite strains has already been reported.56,57 Considering that the CTL response is a function of the host MHC type/TCR repertoire and antigenic types of parasites, the positive selective pressure acting on a particular gene may be too weak to be detected. In addition, CTL recognizes short peptides presented by MHC class I molecules, and, therefore, immune-based selective pressure is likely to be focused on a limited region of the targeted genes that dN/dS analysis is not sensitive enough to detect.

The selected 71 antigen list also contained several genes from 3 large gene families, namely the Tash gene family (Ortholog group number: PiroF0100038), the SVSP gene family (PiroF0100037), and FAINT super family (PiroF0100056, also called as SfiI-subtelomeric fragment related protein family member). The Tash gene family has been characterized extensively in T. annulata.58 Some of the Tash and SVSP gene products have been predicted or demonstrated to be translocated in the host nucleus, and most of the Tash and SVSP genes are expressed predominantly in the schizont stage.58,59 This entails that the potential selective pressure will not be humoral, although the possibility that these proteins are exposed to the humoral immune response when infected cells are lysed cannot be excluded. A previous comparison between T. annulata and T. parva genomes also revealed high inter-species dN/dS ratios for the Tash and the SVSP family,60 consistent with our analysis. It was argued that gene expansion and divergence of Tash and SVSP family genes were associated with different functionality in each species.

In conclusion, this study highlighted the phylogenetic relationship of 10 T. parva strains based on full genome sequences with prediction of possible past recombination events. The high-density SNPs map developed in this study is now applicable for genotyping or linkage analysis of the parasite. Practically, SNPs-based genotyping can discriminate vaccine and field strains of T. parva. Recent methodological advances in high-throughput technologies such as Taq man-real-time PCR and Golden gate technologies61 for SNPs genotyping will likely facilitate future genotyping studies. Further phylogenetic analysis in combination with phenotypic data will assist in the investigation of the virulence and evolution of bovine theilerias after their diversification from buffalo. Importantly, the putative antigen-encoding genes listed in this study should be further investigated to assess their candidacy as Theileria subunit vaccine components.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Data are available at www.dnaresearch.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research and Asia-Africa S & T Strategic Cooperation Promotion Program by the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science & Technology, from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MEXT) to C.S. K.H. was supported by the Program of Founding Research Centers for Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases, MEXT.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Edited by Dr Takao Sekiya

References

- 1.Brown C.G., Stagg D.A., Purnell R.E., Kanhai G.K., Payne R.C. Letter: infection and transformation of bovine lymphoid cells in vitro by infective particles of Theileria parva. Nature. 1973;245:101–3. doi: 10.1038/245101a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence J.A., Irvin A.D. Theilerioses. In: Coetzer J.A.W., Thomson G.R., Tustin R.C., editors. Infectious Diseases of Livestock. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. pp. 307–41. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uilenberg G. Theileria species of domestic livestock. In: Irvun A.D., Cunningham M.P., Young A.S., editors. Advances in the Control of Theileriosis. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1981. pp. 4–37. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young A.S., Purnell R.E. Transmission of Theileria lawrencei (Serengeti) by the ixodid tick, Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 1973;5:146–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02251383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown C.G., Radley D.E., Burridge M.J., Cunningham M.P. The use of tetracyclines on the chemotherapy of experimental East Coast Fever (theileria parva infection of cattle) Tropenmed. Parasitol. 1977;28:513–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geysen D., Bishop R., Skilton R., Dolan T.T., Morzaria S. Molecular epidemiology of Theileria parva in the field. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 1999;4:A21–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oura C.A., Bishop R., Wampande E.M., Lubega G.W., Tait A. The persistence of component Theileria parva stocks in cattle immunized with the ‘Muguga cocktail’ live vaccine against East Coast fever in Uganda. Parasitology. 2004;129:27–42. doi: 10.1017/s003118200400513x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oura C.A., Bishop R., Asiimwe B.B., Spooner P., Lubega G.W., Tait A. Theileria parva live vaccination: parasite transmission, persistence and heterologous challenge in the field. Parasitology. 2007;134:1205–13. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007002557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKeever D.J. Live immunisation against Theileria parva: containing or spreading the disease? Trends Parasitol. 2007;23:565–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkvens D.L. Re-assessment of tick control after immunization against East Coast fever in the Eastern Province of Zambia. Ann. Soc. Belg. Med. Trop. 1991;71:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel E.H., Lubembe D.M., Gachanja J., Mwaura S., Spooner P., Toye P. Molecular characterization of live Theileria parva sporozoite vaccine stabilates reveals extensive genotypic diversity. Vet. Parasitol. 2011;179:62–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bishop R., Geysen D., Spooner P., et al. Molecular and immunological characterisation of Theileria parva stocks which are components of the ‘Muguga cocktail’ used for vaccination against East Coast fever in cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 2001;94:227–37. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(00)00404-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minami T., Spooner P.R., Irvin A.D., Ocama J.G., Dobbelaere D.A., Fujinaga T. Characterisation of stocks of Theileria parva by monoclonal antibody profiles. Res. Vet. Sci. 1983;35:334–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oura C.A., Odongo D.O., Lubega G.W., Spooner P.R., Tait A., Bishop R.P. A panel of microsatellite and minisatellite markers for the characterisation of field isolates of Theileria parva. Int. J. Parasitol. 2003;33:1641–53. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oura C.A., Asiimwe B.B., Weir W., Lubega G.W., Tait A. Population genetic analysis and sub-structuring of Theileria parva in Uganda. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2005;140:229–39. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katzer F., Ngugi D., Oura C., et al. Extensive genotypic diversity in a recombining population of the apicomplexan parasite Theileria parva. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:5456–64. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00472-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katzer F., Ngugi D., Walker A.R., McKeever D.J. Genotypic diversity, a survival strategy for the apicomplexan parasite Theileria parva. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;167:236–43. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katzer F., Lizundia R., Ngugi D., Blake D., McKeever D. Construction of a genetic map for Theileria parva: identification of hotspots of recombination. Int. J. Parasitol. 2011;41:669–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radley D.E., Brown C.G., Cunnigham M.P., et al. East Coast fever: challenge if immunised cattle by prolonged exposure to infected ticks. Vet. Rec. 1975;96:525–7. doi: 10.1136/vr.96.24.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugimoto C., Conrad P.A., Ito S., Brown W.C., Grab D.J. Isolation of Theileria parva schizonts from infected lymphoblastoid cells. Acta Trop. 1988;45:203–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goddeeris B.M., Dunlap S., Innes E.A., McKeever D.J. A simple and efficient method for purifying and quantifying schizonts from Theileria parva-infected cells. Parasitol. Res. 1991;77:482–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00928414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baumgartner M., Tardieux I., Ohayon H., Gounon P., Langsley G. The use of nocodazole in cell cycle analysis and parasite purification from Theileria parva-infected B cells. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1181–8. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asao T., Kinoshita Y., Kozaki S., Uemura T., Sakaguchi G. Purification and some properties of Aeromonas hydrophila hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 1984;46:122–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.1.122-127.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosono S., Faruqi A.F., Dean F.B., et al. Unbiased whole-genome amplification directly from clinical samples. Genome Res. 2003;13:954–64. doi: 10.1101/gr.816903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silander K., Saarela J. Whole genome amplification with Phi29 DNA polymerase to enable genetic or genomic analysis of samples of low DNA yield. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;439:1–18. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-188-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardner M.J., Bishop R., Shah T., et al. Genome sequence of Theileria parva, a bovine pathogen that transforms lymphocytes. Science. 2005;309:134–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1110439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brockman W., Alvarez P., Young S., et al. Quality scores and SNP detection in sequencing-by-synthesis systems. Genome Res. 2008;18:763–70. doi: 10.1101/gr.070227.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Z., Nielsen R., Goldman N. In defense of statistical methods for detecting positive selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:E95. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904550106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1586–91. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen T.N., Brunak S., von Heijne G., Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:785–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bryant D., Moulton V. Neighbor-net: an agglomerative method for the construction of phylogenetic networks. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:255–65. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huson D.H., Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:254–67. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin D.P., Lemey P., Lott M., Moulton V., Posada D., Lefeuvre P. RDP3: a flexible and fast computer program for analyzing recombination. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2462–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Padidam M., Sawyer S., Fauquet C.M. Possible emergence of new geminiviruses by frequent recombination. Virology. 1999;265:218–25. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith J.M. Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. J. Mol. Evol. 1992;34:126–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00182389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Posada D. Evaluation of methods for detecting recombination from DNA sequences: empirical data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002;19:708–17. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin D., Rybicki E. RDP: detection of recombination amongst aligned sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:562–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin D.P., Posada D., Crandall K.A., Williamson C. A modified bootscan algorithm for automated identification of recombinant sequences and recombination breakpoints. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2005;21:98–102. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boni M.F., Posada D., Feldman M.W. An exact nonparametric method for inferring mosaic structure in sequence triplets. Genetics. 2007;176:1035–47. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.068874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gibbs M.J., Armstrong J.S., Gibbs A.J. Sister-scanning: a Monte Carlo procedure for assessing signals in recombinant sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:573–82. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.7.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimura M. Recent development of the neutral theory viewed from the Wrightian tradition of theoretical population genetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:5969–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.5969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Endo T., Ikeo K., Gojobori T. Large-scale search for genes on which positive selection may operate. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1996;13:685–90. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pain A., Renauld H., Berriman M., et al. Genome of the host-cell transforming parasite Theileria annulata compared with T. parva. Science. 2005;309:131–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1110418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayashida K., Hara Y., Abe T., et al. Comparative genome analysis of three eukaryotic parasites with differing abilities to transform leukocytes reveals key mediators of Theileria-induced leukocyte transformation. MBio. 2012;3:e00204–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00204-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skilton R.A., Musoke A.J., Wells C.W., et al. A 32 kDa surface antigen of Theileria parva: characterization and immunization studies. Parasitology. 2000;120:553–64. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099005934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sako Y., Asada M., Kubota S., Sugimoto C., Onuma M. Molecular cloning and characterisation of 23-kDa piroplasm surface proteins of Theileria sergenti and Theileria buffeli. Int. J. Parasitol. 1999;29:593–9. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(99)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hellmann I., Prufer K., Ji H., Zody M.C., Paabo S., Ptak S.E. Why do human diversity levels vary at a megabase scale? Genome Res. 2005;15:1222–31. doi: 10.1101/gr.3461105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michelizzi V.N., Wu X., Dodson M.V., et al. A global view of 54,001 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on the Illumina BovineSNP50 BeadChip and their transferability to water buffalo. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2010;7:18–27. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chan E.R., Menard D., David P.H., et al. Whole genome sequencing of field isolates provides robust characterization of genetic diversity in Plasmodium vivax. PLoS. Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012;6:e1811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young A.S., Brown C.G., Burridge M.J., et al. The incidence of theilerial parasites in East African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) Tropenmed. Parasitol. 1978;29:281–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Conrad P.A., Stagg D.A., Grootenhuis J.G., et al. Isolation of Theileria parasites from African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) and characterization with anti-schizont monoclonal antibodies. Parasitology. 1987;94:413–23. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000055761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bradley D.G., MacHugh D.E., Cunningham P., Loftus R.T. Mitochondrial diversity and the origins of African and European cattle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:5131–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.5131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hanotte O., Tawah C.L., Bradley D.G., et al. Geographic distribution and frequency of a taurine Bos taurus and an indicine Bos indicus Y specific allele amongst sub-saharan African cattle breeds. Mol. Ecol. 2000;9:387–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanotte O., Bradley D.G., Ochieng J.W., Verjee Y., Hill E.W., Rege J.E. African pastoralism: genetic imprints of origins and migrations. Science. 2002;296:336–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1069878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Collins N.E., Allsopp B.A. Theileria parva ribosomal internal transcribed spacer sequences exhibit extensive polymorphism and mosaic evolution: application to the characterization of parasites from cattle and buffalo. Parasitology. 1999;118:541–51. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099004321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacHugh N.D., Weir W., Burrells A., et al. Extensive polymorphism and evidence of immune selection in a highly dominant antigen recognized by bovine CD8 T cells specific for Theileria annulata. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:2059–69. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01285-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacHugh N.D., Connelley T., Graham S.P., et al. CD8+ T-cell responses to Theileria parva are preferentially directed to a single dominant antigen: implications for parasite strain-specific immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:2459–69. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swan D.G., Phillips K., Tait A., Shiels B.R. Evidence for localisation of a Theileria parasite AT hook DNA-binding protein to the nucleus of immortalised bovine host cells. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1999;101:117–29. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmuckli-Maurer J., Casanova C., Schmied S., et al. Expression analysis of the Theileria parva subtelomere-encoded variable secreted protein gene family. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weir W., Sunter J., Chaussepied M., et al. Highly syntenic and yet divergent: a tale of two Theilerias. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2009;9:453–61. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ragoussis J. Genotyping technologies for genetic research. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2009;10:117–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.