Abstract

Although functional capacity is typically diminished, there is substantial heterogeneity in functional outcomes in schizophrenia. Motivational factors likely play a significant role in bridging the capacity-to-functioning gap. Self-efficacy theory suggests that although some individuals may have the capacity to perform functional behaviors, they may or may not have confidence they can successfully perform these behaviors in real-world settings. We hypothesized that the relationship between functional capacity and real-world functioning would be moderated by the individual’s self-efficacy in a sample of 97 middle-aged and older adults with schizophrenia (mean age = 50.9 ± 6.5 years). Functional capacity was measured using the Brief UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA-B), self-efficacy with the Revised Self-Efficacy Scale, and Daily Functioning via the Specific Level of Functioning (SLOF) scale and self-report measures. Results indicated that when self-efficacy was low, the relationship between UPSA-B and SLOF scores was not significant (P = .727). However, when self efficacy was high, UPSA-B scores were significantly related to SLOF scores (P = .020). Similar results were observed for self-reported social and work functioning. These results suggest that motivational processes (ie, self-efficacy) may aid in understanding why some individuals have the capacity to function well but do not translate this capacity into real-world functioning. Furthermore, while improvement in capacity may be necessary for improved functioning in this population, it may not be sufficient when motivation is absent.

Keywords: functioning, psychosis, motivation, control, recovery

Introduction

Although the global prevalence rate of schizophrenia ranges from 0.3% to 1.6%,1 it is among the most debilitating and most expensive mental disorders in terms of direct treatment costs, loss of productivity, and expenditures for public assistance. Estimates place schizophrenia’s cost to society at over $62 billion annually.2 A sizeable portion of these costs are believed to come from patients’ diminished capacity for learning, working, self-care, interpersonal relationships, and maintaining general living skills.3 Numerous studies have identified reduced functional capacity as a key barrier to functioning among patients with schizophrenia.4–6 Many individuals with schizophrenia have the desire to reside independently7 and/or to work.8 However, reduced functional capacity, coupled with the deinstitutionalization of those with severe mental illnesses, have contributed to very low rates of employment and increased reliance upon supervised living arrangements (eg, board and care facilities).9

Despite the known deficits to functioning often found among individuals with schizophrenia, many maintain or develop the capacity to function successfully in their communities. Healthcare professionals are often called upon to evaluate which individuals are most likely capable of functioning independently. However, clinical judgment alone may not be sufficient given that clinicians are not typically embedded in the natural environment of those with whom they work. Therefore, an individual’s “real-world” functioning can be extremely difficult to accurately assess.

To address this limitation, clinicians often rely on additional measures to assess functional capacity. Yet, despite growing efforts over past decades, the development of a “gold standard” measure that captures one’s capacity to function in real-world settings has been elusive. A recent review of methods that assess functioning in this population found that performance-based methods exceed other methods (eg, clinical judgment) in terms of reliability and validity.10 One criticism is that while these measures may capture a person’s capacity to perform real-world tasks, capacity does not always translate to real-world functioning.11,12 Instead, efforts to assess real-world functioning should at least partially rely on third party ratings of actual real-world behavior.13 Thus, a crucial yet unanswered question remains: “For whom, and under what circumstances, does functional capacity converge with real-world functioning?”

To date, only one published study has examined the factors associated with a gap between capacity and functioning. Gupta and colleagues14 found poorer clinical course of illness (eg, earlier onset and greater time spent institutionalized), more depressive symptoms, and restricted living circumstances accurately classified those who evidenced poor real-world functioning in spite of having adequate capacity to perform everyday behaviors. Although classification rates in this study were adequate, the addition of key intrapersonal factors may further improve our prediction of who is likely to underperform in the everyday environment.

Intrapersonal factors likely play a significant role in bridging the capacity-to-functioning gap. Among these intrapersonal factors, self-efficacy represents one of the strongest theoretical candidates. According to Bandura,15 self-efficacy is an individual’s belief that s/he can successfully perform a specific behavior. In his theoretical framework, Bandura specifically indicates there is a discernible difference between having the capacity (ie, possessing knowledge and skills) to perform a task and actually performing it well. According to self-efficacy theory, performing well in real-world circumstances is a function of having both the skills and the self-belief that one can utilize them. Therefore, 2 persons with equivalent knowledge and skill sets may perform poorly, adequately, or extraordinarily depending on differences in their self-efficacy. As seen in his writings, Bandura’s conceptualization of self-efficacy focused on one’s confidence in performing specific tasks (eg, confidence in running a 5-min mile). Others, however, have noted the role of broader efficacy beliefs on performance. Specifically, Eccles and Wigfield16 suggest that one’s expectation for success on upcoming tasks is critical for successful performance of the task. However, in contrast to Bandura, they suggest that efficacy beliefs need not be specific to the task being performed but rather can fall within a broader domain (eg, athletic efficacy vs being able to run a 5-min mile). They go on to state that in real-world achievement situations, task-specific (beliefs about running a mile) vs domain-specific (beliefs about academic abilities) are indistinguishable.

Bandura15 also noted the manner in which people attribute successes and failures as playing an important role in motivation. Specifically, individuals who believe their successes are due to their own abilities and simultaneously believe their failures are due to low effort are theorized to be far more likely to undertake difficult tasks and persist in the face of failure. In contrast, individuals who attribute their failures to lack of capacity and their successes to situational factors are theorized to have reduced determination and be far more likely to resign when challenged. He goes on to state, however, that efficacy beliefs mediate the link between attributions and effort, whereby self-efficacy supplies the motivation to pursue a desired outcome. The links between attributions, self-efficacy, and performance attainment have been shown in various studies including elementary-aged students17,18 and patients with schizophrenia,19 whereby increased self-efficacy was the catalyst behind greater effort and superior performance.

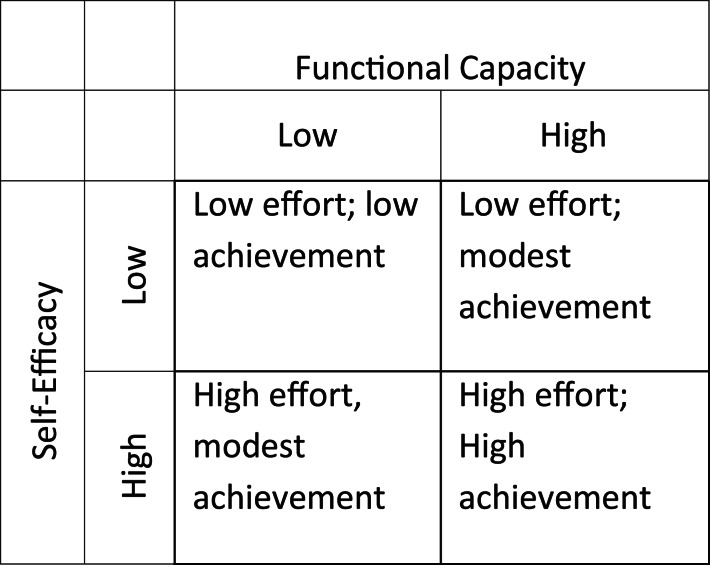

Thus, application of self-efficacy theory to functioning in schizophrenia suggests that although some individuals may have the capacity to perform functional behaviors, they may or may not have confidence that they can successfully perform these behaviors in real-world settings. Given 2 individuals with the same capacity, one who has confidence and the other does not, theory would dictate that the individual with confidence would outperform the one without in functional behaviors because motivation would ultimately dictate the level of effort exerted to achieve outcomes. The theoretical framework for the combined effects of self-efficacy and capacity on functional attainment is displayed graphically in figure 1. The current study directly tests the application of this model. In a sample of 97 middle-aged and older adults with schizophrenia, we hypothesized that the relationship between functional capacity and real-world functioning, as measured by both proxy and self-report, would be moderated by the individual’s self-efficacy, such that functional capacity would be more strongly correlated with real-world functioning when self-efficacy was high vs low.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical interactive effects of self-efficacy and functional capacity on real-world functional attainment.

Methods

Participants

A total of 97 patients with schizophrenia were enrolled in a randomized trial examining the efficacy of 2 psychosocial, skills-training interventions for improving functioning in middle-aged and older adults with a current schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder diagnosis. Data from this study were all collected prior to participants receiving any treatment (ie, baseline assessment). To be eligible, participants were required to be at least 40 years of age, have a physician-determined diagnosis of either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder that was verified by reviewing medical records for consistency of this diagnosis and to be psychiatrically stable (eg, taking antipsychotic medications and not an inpatient at baseline). Participants were primarily recruited from local day treatment or board-and-care facilities via presentation of the project by research staff. The study protocol was approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board (IRB) and all participants provided informed consent prior to enrolling in the study.

Measures

Daily Functioning.

Participants’ everyday functioning was assessed using the Specific Level of Functioning (SLOF) scale. For this scale, an informant rates the participant’s ability to perform 43 specific functional tasks encompassing 6 domains: (a) physical functioning (eg, vision, hearing, and walking), (b) personal care skills (eg, eating, personal hygiene, and dressing), (c) interpersonal relationships (eg, forming and maintaining friendships, initiating contact with others), (d) social acceptability (eg, verbally or physically abusing others, performing repetitive behaviors), (e) activities (eg, shopping, self-medication, handling personal finances using a telephone), and (f) work skills (eg, has employable skills, works with minimal supervision). Ratings are made on a 5-point Likert scale indicating the level of assistance the participant needs to perform the task, with higher score indicating better functioning. For all subjects in this study, ratings were provided by either a board-and-care manager or a caseworker familiar with the patient’s level of functioning. The SLOF has excellent reliability and validity20 and is commonly used to assess functioning in patients with schizophrenia.21–23 The physical functioning, personal care skills, and social acceptability scales assess basic (lower order) functioning, whereas the daily activities, work skills, and interpersonal relationships subscales assess higher order functional activities. Research has identified that the lower order tasks assessed by the SLOF are typically highly intact in schizophrenia populations, 22 whereas “higher order tasks” demonstrate varying levels of impairment. Furthermore, these “higher” and “lower” order domains were confirmed in our data by way of a principal components analysis, which found the daily activities, work skills, and interpersonal relationships subscales loading on component 1 and the physical functioning, personal care skills, and social acceptability scales loading on component 2. Because the emphasis of this study was on these higher order functional abilities, we calculated a total functioning score using the sum of the daily activities, work skills, and interpersonal relationships scales.

In addition to informant reports, participants completed Work/School Impairment and Social Impairment subscales of the Behavioral Activation for Depression scale (BADS).24 Each of these subscales consists of 5 items assessing the participant’s level of impairment in everyday responsibilities (eg, my responsibilities suffered because I was not as active as I needed to be; I was active but did not accomplish any of my goals for the day) and social engagement (eg, I was not social, even though I had opportunities to be; I did not see any of my friends) over the past week. Where applicable, items on the Work/School Impairment subscale were reworded to utilize the word “responsibilities” in place of Work/School due to relatively low rates of employment/schooling in our sample. All items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 6 (completely), with higher scores indicating greater impairment. With questions related to the frequency of behaviors, rather than the distress or enjoyment associated with them, the BADS provides an objective self-report of the person’s quality of life; objective quality of life scales have stronger psychometric properties than subjective measures in schizophrenia.25 The coefficients alpha for the work and social impairment subscales in our sample was .73 and .84, respectively.

Functional Capacity.

All participants completed the brief version of the UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA-B),26 which assesses a person’s “capacity” to perform a variety of everyday living tasks. For this test, participants are asked to role-play tasks from 2 domains they are likely to encounter during their everyday lives: (a) Finance (eg, capacity to count change and write checks) and (b) Communication (eg, an emergency phone call; reschedule a doctor’s appointment). Participants receive scaled scores for each of the subscales (range = 0–50), which are summed to create an overall score ranging from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate better functional capacity. Reliability and validity of the UPSA-B are excellent,26 and the UPSA-B has been validated to predict real-world outcomes, such as residential independence,26 community responsibilities,27 and work.28

Self-Efficacy.

Participants were administered a Revised Self-efficacy Scale (RSES) to assess level of confidence in exerting control over symptoms associated with their illness and for performing certain desired behaviors.29 Ratings are based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all confident) to 5 (Extremely confident). The RSES was developed specifically for use with schizophrenia populations, with the 35 items are broken up into 2 different subscales representing one’s self-efficacy for: (a) performing everyday functioning tasks (eg, “Go shopping for groceries,” “Go to a job interview,” “Go shopping for clothes,” “Keep your living quarters clean,” “Attend classes”) and (b) engaging in social activities (eg, “Begin a conversation with a friend,” “Introduce yourself to someone you don’t know”). Because our outcomes involved everyday functional tasks such as work and daily activities (eg, shopping and handling finances), we used the 19 items assessing participants’ confidence in performing everyday functional tasks. For the current sample, coefficient alpha was .91.

Clinical Symptoms.

Participants were interviewed and their clinical symptoms rated by a trained research assistant using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).30 The PANSS consists of 30-items assessing positive (7 items), negative (7 items), and general symptoms of mental illness (16 items). Each of the items is rated on a 7-point severity scale, and subscale and total scores are created by summing the items. Higher scores indicate greater symptom severity.

Antipsychotic Medication Dosage.

We conducted chart reviews of medication use (ie, amounts, types, and frequencies of antipsychotic medication use). Typical and atypical medications were converted to milligrams chlorpromazine equivalents using published formulas.31

Data Analysis

Prior to analyzing our data, all linear variables were centered at their means. As described by Kraemer and Blasey,32 centering variables serves to produce regression coefficients and intercepts that are relevant and also aids in reducing problems associated with multicollinearity. Given their association with functional outcomes,33–35 age in years and PANSS negative scores were used as covariates in our analyses. After accounting for these variables, self-efficacy, UPSA-B scores, and the interaction between self-efficacy and UPSA-B were entered into our models.

The primary focus of our analysis was the interaction term. If significant (P < .05), it suggested the relationship between functional capacity and daily functioning was moderated by self-efficacy. Post hoc analyses were conducted to determine the nature of the interaction.36 Prior to these analyses, we created a high self-efficacy (ie, centered self-efficacy – 1 SD) and low self-efficacy variable (ie, centered self-efficacy + 1 SD). Each of these variables was then multiplied by the (centered) UPSA-B variable to create interaction terms. With these variables, we conducted 2 additional regression analyses, each of which included the main effect for UPSA-B, one of the conditional self-efficacy variables (high self-efficacy or low self-efficacy), and the interaction of the UPSA-B and self-efficacy variable (ie, UPSA-by-low self efficacy and UPSA-by-high self efficacy). The primary effect examined in each of these post hoc analyses was the association between UPSA-B score and functional outcome, as this association helped us determine the slope between UPSA-B and functioning for low and high levels of self-efficacy. For more details on this approach, see Holmbeck et al36

In addition to conducting post hoc analyses to determine the nature of our interactions (at −1 and +1 SDs), we calculated the region of significance using the procedure described by Preacher and colleagues.37 As explained by Preacher et al, the region of significance defines the specific values of self-efficacy at which the regression of functional outcomes on functional capacity moves from nonsignificance to significance.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The mean age of our participants was 50.9 years (SD = 6.5), with 55 males (56.7%) and 42 females (43.3%). Participants had an average of 12.3 years of education (SD = 2.3). A total of 48 participants identified themselves as Caucasian (49.5%), 23 (23.7%) as African American, 18 (18.6%) as Hispanic/Latino, 5 (5.2%) as American Indian, and 3 (3.1%) as Asian/Pacific Islander. Seventy-three participants (75.3%) were diagnosed with Schizophrenia and the remaining 24 (24.7%) were diagnosed with Schizoaffective Disorder. Means, SDs, and correlations among primary study variables are reported in table 1.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations, Means, and SDs for Primary Study Variables

| 1. Age | 2. PANSS Negative | 3. PANSS Positive | 4. Self-Efficacy | 5. UPSA-B | 6. SLOF Composite | 7. BADS Work Impairment | 8. BADS Social Impairment | |

| 1. | — | |||||||

| 2. | .12 | — | ||||||

| 3. | .12 | .33* | — | |||||

| 4. | −.04 | −.19 | −.13 | — | ||||

| 5. | −.13 | −.44* | −.20* | .06 | — | |||

| 6. | .03 | −.24* | .00 | .14 | .22* | — | ||

| 7. | .11 | .30* | .29* | −.21* | −.22* | −.31* | — | |

| 8. | .09 | .38* | .39* | −.22* | −.35* | −.26* | .67* | — |

| M (SD) | 50.9 (6.5) | 15.2 (5.2) | 14.8 (6.4) | 61.0 (14.1) | 54.0 (21.5) | 98.8 (15.7) | 10.1 (6.3) | 11.8 (7.9) |

Note: N = 97. UPSA-B, UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment—Brief; SLOF, Specific Level of Functioning; BADS, Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

*P < .05.

Proxy Report of Patient Functioning

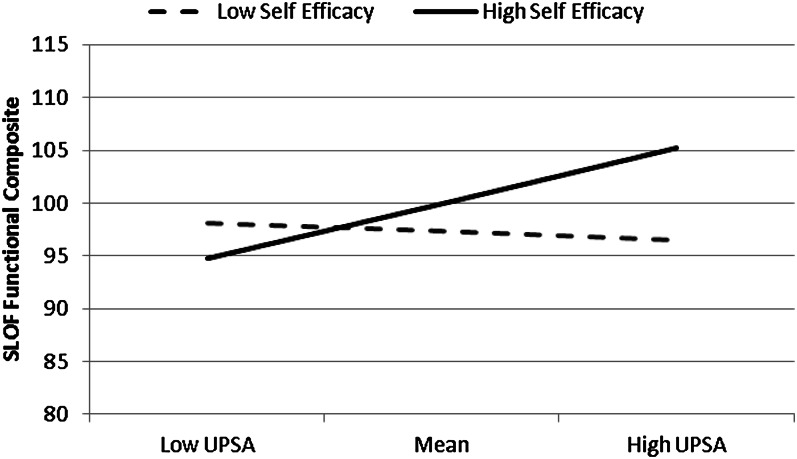

Our first regression examined the moderating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between UPSA-B scores and scores on the SLOF functioning composite. However, the UPSA-B × SE interaction for this model was significant (P = .049). We then examined the relationship between UPSA-B and SLOF composite scores for low vs high self-efficacy, with the corresponding slopes presented in figure 2. When self-efficacy was low (−1 SD), the relationship between UPSA-B and SLOF composite was not significant (B = −0.039 ± 0.110; t = −0.35, df = 91, P = .727). However, when self-efficacy was high (+1 SD), UPSA-B scores were significantly related to everyday functioning (B = 0.242 ± 0.102; t = 2.364, df = 91, P = .020). When calculating the region of significance, we estimated that UPSA-B scores significantly predicted everyday functioning when participants scored 67 or higher on the self-efficacy scale (ie, on average, slightly greater than moderate confidence in their capacity to perform functional behaviors).

Fig. 2.

Interaction between functional capacity (Brief UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment [UPSA-B]) and self-efficacy in predicting real-world functioning.

Self-Report of Functional Impairment

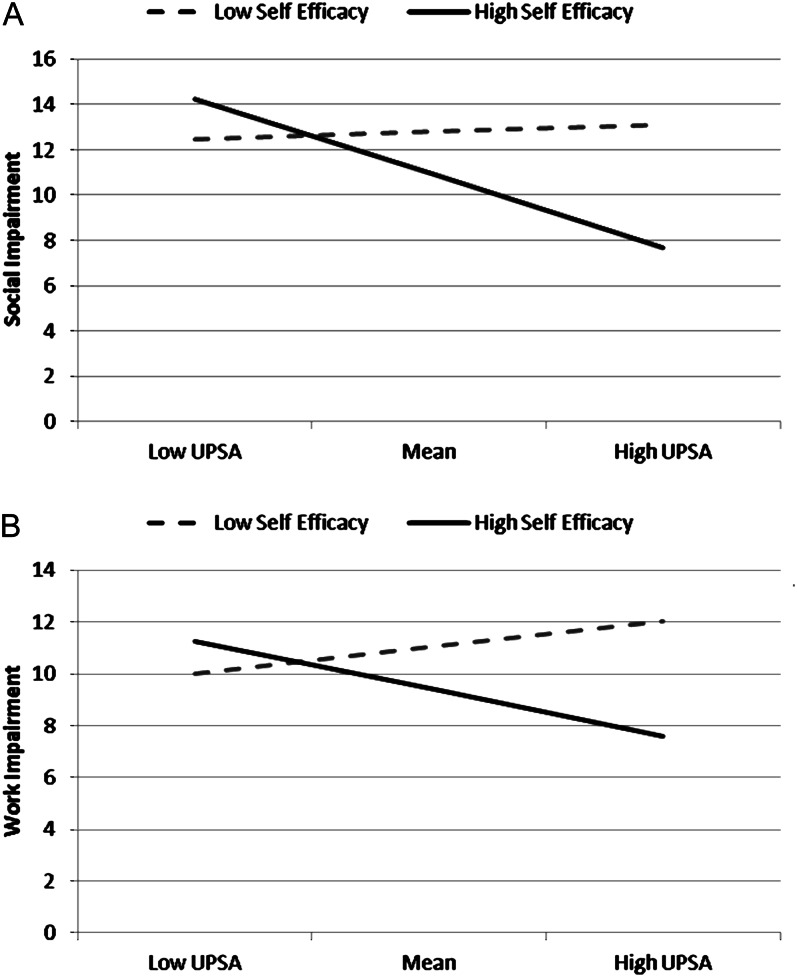

Our final 2 regressions examined the moderating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between UPSA-B scores and self-reported social impairment and impairment in work/responsibilities. Results for social impairment yielded a significant UPSA-B × SE interaction (P = .007). Post hoc analyses indicated that when self-efficacy was low (−1 SD), UPSA-B scores were not significantly related to impairment (B = 0.013 ± 0.051; t = 0.252, df = 91, P = .802). However, when self-efficacy was high (+1 SD), higher UPSA-B scores were associated with lower impairment (B = −0.166 ± 0.047; t = −3.528, df = 91, P = .001). We estimated that UPSA-B scores significantly predicted lower functional impairment when participants scored 59 or higher on the self-efficacy scale (ie, on average, moderate confidence in their capacity to perform functional behaviors).

We also observed a significant UPSA-B × SE interaction for work/responsibility impairment (P = .011). Post hoc analyses indicated that when self-efficacy was low, UPSA-B scores were not significantly related to impairment (B = 0.046 ± 0.043, df = 91, P = .285). In contrast, UPSA-B was significantly related to impairment when self-efficacy was high (B = −0.096 ± 0.040, t = −2.403, df = 91, P = .018). The interactions for the impairment scales are displayed in figure 3. The region of significance for this analysis was 70, indicating that UPSA-B was significantly related to work/responsibility impairment when self-efficacy was 70 or higher (ie, on average, between moderate and high levels of confidence in their capacity to perform functional behaviors).

Fig. 3.

Interaction between functional capacity (Brief UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment [UPSA-B]) and self-efficacy in predicting both social impairment (Panel A, top) and work impairment (Panel B, bottom).

Discussion

These results indicate that self-efficacy accounts for a significant proportion of the functional capacity-performance gap. Only among individuals with higher self-efficacy was capacity significantly related to real-world daily functioning and lower impairments to social interactions and work/responsibilities. No such relationship was evident among patients with low self-efficacy. Results of all 3 analyses indicated that, without confidence in their ability to perform functional tasks, individuals who otherwise have the capacity will maintain relatively high levels of impairment in their lives. In more basic terms, our results suggest that even if 2 individuals have equivalent ability (ie, capacity) to successfully perform skills (eg, manage finances, shop for groceries), they will not demonstrate equal performance of these skills in real-life circumstances. More specifically, among individuals with a high degree of skill, those with less than moderate confidence in their abilities will continue to show impairment in daily life, whereas those with greater confidence will use these skills more successfully. Therefore, interventions targeting self-efficacy to perform daily living tasks may be beneficial for improving the real-world benefits associated with improved capacity.

As demonstrated in previous research, the UPSA-B has achieved satisfactory validity in predicting real-world functional milestones. The current findings enhance the potential clinical value of this tool by providing contexts under which the UPSA-B may, or may not, be capable of predicting functional outcomes. This becomes particularly important in 2 clinical contexts. First, if the UPSA-B (or other measures of functional capacity) is to be used to make clinical decisions/recommendations about an individual’s residential or work circumstances, clinicians should consider evaluating the patient’s level of self-efficacy. In our study, capacity was significantly associated with functioning only when participants scored above 60 on the self-efficacy scale. This corresponds to reporting more than 50% confidence in one’s ability to perform various functional tasks (eg, go shopping for groceries; remember to pay your bills). Thus, if individuals have reasonable capacity, but indicate reduced confidence they can perform functional tasks, it appears less likely that the individual will successfully perform functional behaviors. Accordingly, clinical decisions may emphasize altering efficacy beliefs within the context of functional capacity.

The second clinical implication of our study corresponds to the use of functional capacity measures in treatment studies. Our findings suggest that while some treatments may result in significant improvements to functional capacity, if the treated individual continues to express diminished confidence in his/her ability to successfully perform functional tasks, relatively little will have been accomplished in terms of true functional performance. Thus, clinical trials may consider incorporating self-efficacy scales to determine if the treatments in question produce significant change to efficacy beliefs or if these beliefs moderate changes to functional outcomes. This may also aid in determining the level of change needed in both functional capacity and self-efficacy to produce meaningful real-world change in functioning.

The results complement previous work14 that has linked course of illness and living circumstances as factors explaining the gap between these 2 levels of functional measurement. In addition to self-efficacy beliefs, we identify a few variables that likely play a role, all of which exert their influence on an individual’s motivational processes. The first is expectations placed on the individual for functional performance and independence. That is, some individuals may have the capacity to perform behaviors, but find themselves in contexts where high levels of functioning are not expected (eg, no need to acquire a job; no need to reside independently). These individuals are theoretically not likely to demonstrate actual functional independence. Indeed, among middle-aged and older adults with schizophrenia, we have previously demonstrated that capacity is related to community responsibilities (eg, work, school, etc.) among those who reside in the community (eg, with family).27 However, this relationship was not existent in patients who resided in board-and-care facilities, which we attributed to the expectations placed on the individual for demonstrating higher levels of functional performance. However, because that study did not conduct an assessment of expectations, we encourage more research on this topic as a means of explaining these moderator effects.

A second construct of importance is the attitude the individual has toward functional outcomes. Theoretically, individuals who have the capacity to function well but who view high functional performance (eg, earn personal income, reside independently) as not beneficial may be less motivated to exert the effort required to achieve these goals. Attitudes toward behavior appear to be strong predictors of both intention to engage in behaviors and actual performance of behaviors for a variety of health behaviors.38–40

Third, outcome expectancies may help merge capacity with performance of a task or behavior. While self-efficacy is the belief that one has the ability to successfully perform a task or behavior, outcome expectancies are the belief that performing the behavior will produce a desired outcome. Capable, efficacious individuals are not expected to engage in related functional behaviors if they do not believe performing them will produce a desired outcome (eg, independent living). This phenomenon may be particularly true in chronic illnesses, such as schizophrenia, where individuals are likely to learn over time that despite demonstrated ability, desired outcomes are not the result. Indeed, in a small sample of outpatients with schizophrenia, Hoffman and colleagues41 found that outcome expectancies were strongly associated with rehabilitation outcome. Furthermore, Gupta and colleagues14 found more restricted living circumstances which likely affect expectancies due to fewer social opportunities, predicted a gap between capacity and functioning.

One limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design. Therefore, we urge caution in interpreting the causality of our results. To determine the causality of the relationships presented here, a longitudinal or experimental design is needed, in which self-efficacy is manipulated in the context of stable functional capacity to determine if changes in self-efficacy produces change in functional outcomes.

Another limitation of our study is that we assessed social impairment and impairment in work/responsibilities by using a measure (ie, the BADS) that has not been extensively used in schizophrenia samples. Furthermore, the BADS asks participants to self-report their social and work functioning. Although participants’ clinical symptoms were relatively low, people with schizophrenia may not provide accurate information on their functioning. However, despite the limitations of using self-report outcomes, we note that patient perspectives on his/her well being are an important aspect of recovery and should not be avoided at a clinical level. Also, results were similar for our self-report and capacity outcome (UPSA-B), thus adding a broader level of support to the role of self-efficacy and functional outcome. Nonetheless, future research should continue this line of research by using self-report measures that have been validated in schizophrenia samples or use assessment tools that capture actual functioning outcomes, such as employment and living situation.

Another limitation is that our sample consisted of middle-aged and older patients with well-managed symptoms of psychosis. Thus, it is unclear how these results generalize to younger patients. We speculate, however, that these results would be even stronger in younger patients. Specifically, our experience has been that patients often report high confidence in their ability to perform certain functional behaviors. However, as patients remain in a “system” that may not allow them to perform independent functional behaviors despite having the skills, there may be a sense of “learned helplessness” taking place as patients age. Whereas younger patients may believe that if they have skills they will achieve functional independence, middle-aged and older patients may not feel these behaviors are truly under their control and therefore may not perform behaviors despite having the skills. Yet, we recommend caution in interpreting our findings for younger populations until future research should replicate them in younger samples.

The tasks measured on the UPSA-B (ie, finance and communication) are not directly correspondent to the tasks measured on the SLOF (eg, household responsibilities, shopping, self-medication, appears to appointments on time). This is important because it is unclear how efficacy beliefs would serve as a moderator when a functional capacity measure more directly corresponded with specific real-world behaviors. This would be important to test in future research. However, as we mentioned above, Eccles and Wigfield16 suggest that efficacy beliefs need not be specific to the tasks being performed in order to predict real-world performance, and our findings suggest that capacity in one area may correlate with functioning in related but not identical areas when broad-based efficacy beliefs are high vs low.

These findings are not theoretically unusual and it is unlikely they are specific to schizophrenia populations. Indeed, history is filled with gifted students or athletes who fail to live up to their potential, and our findings demonstrate that this is true also among those with schizophrenia. However, unlike students, athletes, or other members of the general population, motivational deficits (or amotivation) are considered hallmark features of schizophrenia,42 perhaps due to pathophysiologic consequences of this illness.42 Therefore, we believe that our findings are particularly valuable in the field of schizophrenia research because they suggest that some individuals develop a stronger sense of confidence and motivation that may allow them to function well despite their illness. Thus, a key future direction is to understand how and why some individuals develop a stronger sense of self-efficacy (and consequently motivation) despite living with an illness in which one of the defining features is avolition.

In sum, we find that functional capacity, as measured by the UPSA-B, was significantly related to multiple measures of functional outcome in participants with high self-efficacy but not low self-efficacy. These results suggest that motivational processes (ie, self-efficacy) may aid in understanding why some individuals have the capacity to function well but do not translate this capacity into real-world functioning. Furthermore, while improvement in capacity may be necessary for improved functioning in this population, it may not be sufficient when motivational processes are absent. Thus, clinical trials designed to improve functional capacity may wish to consider motivational processes as treatment targets, and clinicians may wish to assess motivation along with capacity when considering the individual’s capacity to function in the real world.

Funding

This work was supported via grants R01 MH084967 and P30 MH080002 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Acknowledgments

The Authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Demler O, et al. Prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1122–1129. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knapp M, Mangalore R, Simon J. The global costs of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:279–293. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liberman RP. Assessment of social skills. Schizophr Bull. 1982;8:62–83. doi: 10.1093/schbul/8.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace CJ. Functional assessment in rehabilitation. Schizophr Bull. 1986;12:604–630. doi: 10.1093/schbul/12.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27:235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owen C, Rutherford V, Jones M, Wright C, Tennant C, Smallman A. Housing accommodation preferences of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:628–632. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.6.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auslander LA, Jeste DV. Perceptions of problems and needs for service among middle-aged and elderly outpatients with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Community Ment Health J. 2002;38:391–402. doi: 10.1023/a:1019808412017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anthony WA, Blanch A. Supported employment for persons who are psychiatrically disabled: an historical and conceptual perspective. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1987;11:5–23. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mausbach BT, Moore R, Bowie C, Cardenas V, Patterson TL. A review of instruments for measuring functional recovery in those diagnosed with psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:307–318. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey PD, Velligan DI, Bellack AS. Performance-based measures of functional skills: usefulness in clinical treatment studies. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1138–1148. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patterson TL, Mausbach BT. Measurement of functional capacity: a new approach to understanding functional differences and real-world behavioral adaptation in those with mental illness. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:139–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leifker FR, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Validating measures of real-world outcome: the results of the VALERO expert survey and RAND panel. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:334–343. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta M, Bassett E, Iftene F, Bowie CR. Functional outcomes in schizophrenia: understanding the competence-performance discrepancy. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:205–211 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eccles JS, Wigfield A. Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:109–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Relich JD, Debus RL, Walker R. The mediating role of attribution and self-efficacy variables for treatment effects on achievement outcomes. Contemp Educ Psychol. 1986;11:195–216. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schunk DH, Gunn TP. Self-efficacy and skill development: influence of task strategies and attributions. J Educ Res. 1986;79:238–244. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi J, Fiszdon JM, Medalia A. Expectancy-value theory in persistence of learning effects in schizophrenia: role of task value and perceived competency. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:957–965. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider LC, Struening EL. SLOF: a behavioral rating scale for assessing the mentally ill. Soc Work Res Abstr. 1983;19:9–21. doi: 10.1093/swra/19.3.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowie CR, Leung WW, Reichenberg A, et al. Predicting schizophrenia patients' real-world behavior with specific neuropsychological and functional capacity measures. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Determinants of real-world functioning performance in Schizophrenia: correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:418–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowie CR, Twamley EW, Anderson H, Halpern B, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. Self-assessment of functional status in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:1012–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanter J, Mulick P, Busch A, Berlin K, Martell C. The behavioral activation for depression scale (BADS): psychometric properties and factor structure. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2007;29:191–202. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tolman AW, Kurtz MM. Neurocognitive predictors of objective and subjective quality of life in individuals with schizophrenia: a meta-analytic investigation. Schizophr Bull. 2011;132:165–170. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mausbach BT, Harvey PD, Goldman SR, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. Development of a brief scale of everyday functioning in persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1364–1372. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mausbach BT, Depp CA, Cardenas V, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. Relationship between functional capacity and community responsibility in patients with schizophrenia: differences between independent and assisted living settings. Community Ment Health J. 2008;44:385–391. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9141-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mausbach BT, Depp CA, Bowie CR, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA-B) for identifying functional milestones in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;132:165–170 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDermott BE. Development of an instrument for assessing self-efficacy in schizophrenic spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:320–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Lindenmayer JP, Opler LA. Positive and negative syndromes in schizophrenia as a function of chronicity. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1986;74:507–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb06276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andreasen NC, Pressler M, Nopoulos P, Miller D, Ho BC. Antipsychotic dose equivalents and dose-years: a standardized method for comparing exposure to different drugs. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraemer HC, Blasey CM. Centring in regression analyses: a strategy to prevent errors in statistical inference. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:141–151. doi: 10.1002/mpr.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. USCD performance-based skills assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27:235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tiznado D, Mausbach BT, Cardenas V, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. UCSD SORT Test (U-SORT): examination of a newly developed organizational skills assessment tool for severely mentally ill adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:916–919. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181fe75b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cardenas V, Mausbach BT, Barrio C, Bucardo J, Jeste D, Patterson T. The relationship between functional capacity and community responsibilities in middle-aged and older Latinos of Mexican origin with chronic psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conner M, Rhodes RE, Morris B, McEachan R, Lawton R. Changing exercise through targeting affective or cognitive attitudes. Psychol Health. 2011;26:133–149. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.531570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawton R, Conner M, McEachan R. Desire or reason: predicting health behaviors from affective and cognitive attitudes. Health Psychol. 2009;28:56–65. doi: 10.1037/a0013424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawton R, Conner M, Parker D. Beyond cognition: predicting health risk behaviors from instrumental and affective beliefs. Health Psychol. 2007;26:259–267. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffmann H, Kupper Z, Kunz B. Hopelessness and its impact on rehabilitation outcome in schizophrenia -an exploratory study. Schizophr Res. 2000;43:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]