Abstract

Associations between trajectories of depressive symptoms and subsequent tobacco and alcohol use were examined in two samples of girls assessed at age 11.5 (T1), 12.5 (T2), and 13.5 (T3). Two samples were examined to ascertain if there was generalizability of processes across risk levels and cultures. Study 1 comprised a United States-based sample of 100 girls in foster care; Study 2 comprised 264 girls in a United Kingdom community-based sample. Controlling for T1 aggression and T1 substance use, individual variation in intercept and slope of depressive symptoms was associated with tobacco use at T3 in both samples: greater intercept and increases in depressive symptoms increased the risk for T3 tobacco use. A similar pattern of associations was found for alcohol use in Study 1. The replicability of findings for the prediction of tobacco use from trajectories of depressive symptoms suggests potential benefit in identifying girls with elevated depressive symptoms for tobacco use prevention programs prior to the transition to secondary school.

Keywords: adolescent girls, alcohol use, tobacco use, depression, longitudinal

Recent reports suggest that depression will become the second leading medical cause of disability in the world by 2020, as measured by premature mortality and years of productive life lost due to disability (World Health Organization, 2001). Further, prevalence rates among young people are rising (Collishaw, Maughan, Goodman, & Pickles, 2004). Although all segments of the population can be affected by depression, adolescent females appear to be particularly vulnerable. Females have significantly higher lifetime prevalence rates of depression than males, with 21% of women meeting criteria for lifetime depression vs. 13% of men (Kessler et al., 1994). The origin of sex differences in depression can be traced to adolescence, at which time an elevated increase in depressive symptoms has been shown in girls as compared to boys (Angold & Costello, 2001; Ge, Lorenz, Conger, Elder, & Simons, 1994; Hankin et al., 1998). This adolescent-onset sex difference has been shown across ethnic groups and sampling criteria (Grant & Compas, 1995; Hyde, Mezulis, & Amramson, 2008).

Although depression is a widely recognized public health concern in its own right, outcomes for adolescent girls with depressive symptoms are often compounded by co-occurring problems with substance use, including alcohol and tobacco use. Numerous studies have shown that depressive symptoms are more highly associated with substance use in girls than in boys (e.g., Gallerani, Garber, & Martin, 2009; Roberts, Roberts, & Xing, 2007; Silberg, Rutter, D’Onofrio, & Eaves, 2003). For example, one study indicated that the odds of a mood disorder among youth with alcohol dependence was 8.0 for girls versus 3.7 for boys (Roberts et al., 2007). A second study followed boys and girls from 8th through 11th grade and found predictive effects of depressive symptoms on girls’ alcohol and tobacco use, but not boys’ (Fleming, Mason, Mazza, Abbott, & Catalano, 2008). As noted by Fleming and colleagues, although extant evidence exists documenting associations between depression and substance use, longitudinal research in this area is sparse (Fleming et al., 2008), particularly during very early adolescence.

Intergenerational studies further highlight the risk of substance use among girls with a family history of depression. Girls with mothers who have a history of a depressive disorder (versus no psychiatric disorders) had more than 6 times the fitted odds of having a substance use disorder during adolescence (Gallerani et al., 2009), and parental depressive symptoms predicted persistent high substance-use impairment in a sample of youth seeking treatment for depression (Goldstein et al., 2009). Together, this body of evidence suggests that relative to boys, girls are at elevated risk for co-occurring depressive symptoms and substance use during adolescence.

A number of mechanisms have been proposed linking the co-occurrence of depression and substance abuse, with models typically hypothesizing either: (1) primary depression, (2) primary substance abuse, (3) a bidirectional interaction between the two, or (4) a common factor which underlies both (Wilhelm, Wedgwood, Niven, & Kay-Lambkin, 2006). When depressive symptoms are hypothesized to be present first, subsequent substance use has been proposed as a means of self-medication (Audrain-McGovern, Rodriguez, & Kassel, 2009; Hammen & Compass, 1994). Alcohol and tobacco are therefore considered to be coping mechanisms to ameliorate the symptoms of depression (Kendler et al., 1993; Kumpfer, Smith, & Summerhays, 2008; Shuckit, Smith, & Chacko, 2006), which may work through neurobiological routes (Nellisery et al., 2003; Vazquez-Palacios, Bonilla-Jaime, & Velazquez-Moctezuma, 2005). When substance use is hypothesized to occur first, the mood altering effects of tobacco and alcohol may directly lead to depressive symptoms (Hasin et al., 1996), or alcohol and nicotine use may gradually alter brain chemistry making an individual more susceptible to depression (Fowler, Logan, Wang, & Volkow, 2003; Pietraszek et al., 1991).

Rather than a simple directional influence, the co-occurrence of depression and substance use may be intertwined, as such, the order of onset is irrelevant. For example, alcohol use may have a depressogenic effect on psychosocial functioning, which in turn increases alcohol use and further decreases functioning (Gilman et al., 2009; Mueser, Drake, & Wallach, 1998). Alternatively, there may be common etiological influences on both depression and substance use. For example, the presence of environmental and genetic pressures are likely to impact both depression and substance use. A family history of alcohol use may contribute to co-occurring depressive symptoms and substance use through the combined presence of a negative family environment and increased genetic liability for abuse (Shuckit et al., 2006). Conversely, there may be an overlap in genetic liability for both depressive and addictive tendencies, leading to a co-occurrence (Breslau, Peterson, Schultz, Chilcoat, & Andreski, 1998; Kendler et al., 1993; Silberg, Rutter, D’Onofrio, & Eaves, 2003). Although not explicitly focused on identifying specific mechanisms of transmission, the present study focuses on the early adolescent period in order to examine the predictive effects of depressive symptoms on later substance use, thereby highlighting self-medication as a potential mechanism underlying their co-occurrence.

The co-occurrence of depressive symptoms with alcohol and tobacco use has been associated with a number of serious outcomes for girls, including suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, conduct problems, and incarceration (Goldstein et al., 2009; Kumpfer, Smith, & Summerhays, 2008). Despite the poor outcomes of such co-occurring problems, substance use has been shown to decrease through specified interventions targeting depression: Adolescents who respond favorably to treatment for depression have been shown to simultaneously display significant improvement in substance use-related impairments (Goldstein et al., 2009), suggesting that understanding the pathways from depressive symptoms to substance use can help inform intervention targets. However, most substance use prevention programs have failed to examine outcomes by gender, and some programs that have conducted separate evaluations for girls have found positive effects for boys but increased substance use among girls (Kumpfer et al., 2008). As noted by the authors of a review (Kumpfer et al.), additional focus on the etiology of substance use in adolescent girls is needed.

The present study focuses on girls’ depressive symptoms and substance use during the early adolescent developmental period—a time in which smoking and alcohol use are often first initiated—to examine the pathways between depressive symptoms and subsequent smoking and alcohol use. Prior work in this area has primarily focused on middle or later adolescence (e.g., Fleming et al., 2008) and neglected the early adolescent period. One of the very few longitudinal studies to focus on depressive symptoms and substance use in childhood and early adolescence found a predictive association between depression among children in Grades 4 to 6 and adolescent tobacco use in Grades 10 to 12 for both boys and girls (Prinstein & La Greca, 2009). Given the increased risks for girls, in the present study, we focused on early adolescent girls and examined longitudinal associations between depressive symptoms, tobacco use, and alcohol use in two independent samples: a United States-based foster care sample and a United Kingdom-based community sample. The dual-sample approach was employed in order to ascertain whether there was generalizability versus specificity in findings across the two countries and by sample risk level (foster care versus community sample), thereby facilitating stronger conclusions if a pattern of findings resulted that could be replicated across studies.

In both the United States and the United Kingdom, the rates of alcohol use for adolescent girls are of national concern. In the United States, data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicated that 26% of girls aged 12–20 reported drinking alcohol in the past month, and 15.5% of girls reported binge drinking (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009a); similarly, 24–29% of 6–7th grade girls in a US-based community sample reported alcohol use in the past 12 months (Brown, Catalano, Fleming, Haggerty, & Abbott, 2005). In the United Kingdom, approximately 24% of 11–15 year olds reported drinking during the past week (Bonomo & Proimos, 2005), with girls as likely to drink as boys and surpassing boys on prevalence rates for binge drinking (Hebbell et. al, 2003).

Rates of tobacco use among adolescent girls are similarly concerning: 9.2% of US girls aged 12–17 reported that they smoke, and smoking initiation rates among girls who have not previously smoked also surpassed boys’ rates (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009a; 2009b). In the United Kingdom, girls have shown consistently higher smoking rates than boys: in 2008, the percentage of 13- and 14-year-old girls who smoked was twice that of boys, with the sex difference remaining by age 15 when 17% of girls were regular smokers (National Centre for Social Research, 2009). Specific to child welfare populations, 31% of girls aged 11–15 who were the subject of a Child Protective Services investigation of child abuse or neglect reported substance use in the past 30 days, with only 47% of such girls reporting that they had never tried any substance (Orton, Riggs, & Libby, 2009). Together, these statistics point to early adolescence as the key developmental period for initiation of alcohol and tobacco use among girls.

Despite the alarming rates of drinking and tobacco use among young adolescent girls, and the poor outcomes associated with co-occurring substance use and depression, little is known about the associations between the trajectories of girls’ depressive symptoms and tobacco and alcohol use during the early adolescent period. Limitations in prior studies have included a failure to examine pathways for girls, cross-sectional designs, examination of trajectories in later adolescence when substance use has often already begun and stabilized, and a focus on normative or clinically-selected samples. The present study addressed these gaps by examining associations between girls’ trajectories of depressive symptoms at age 11.5, 12.5, and 13.5 as a predictor of tobacco and alcohol use at age 13.5. Because aggression and conduct problems are known to be associated with both depressive symptoms and substance use in girls (e.g., Fergusson & Woodward, 2000), we controlled for initial levels of aggression in our models. We hypothesized that individual differences in baseline rates of depressive symptoms and increases in depressive symptoms across the early adolescent period would predict greater prevalence of tobacco and alcohol use in two independent samples.

Method

Participants

Study 1

Study 1 contained 100 girls in foster care who were completing primary school and making the transition to secondary school at the time of recruitment (M age = 11.54, SD = .48). Eligible study participants comprised girls living in state-supported foster homes in one of two counties containing major metropolitan areas in the Pacific Northwest, United States, and who were finishing primary school between 2004 and 2007. The girls were referred through the local child welfare systems. From the pool of participants who met the above criteria (N = 145), 100 girls and their foster parents were recruited during the spring of their final year of primary school (typically fifth grade, with a range of fourth–sixth grade). Recruitment occurred on a rolling basis every spring for 4 years, and ceased when enrollment reached 100 participants. The ethnic distribution of the girls was 63% European American, 14% multiracial, 10% Latino, 9% African American, and 4% Native American. The mean age at foster care entry was 7.63 years (SD = 3.14), and the mean time in foster care was 2.90 years (SD = 2.25).

Study 1 participants were part of a longitudinal intervention trial in which girls were randomly assigned either to a behavioral support intervention condition (n = 48) or to a regular foster care control condition (n = 52; Chamberlain, Leve, & Smith, 2006). The intervention included parenting groups and girl groups and focused on preventing the onset of behavioral and health-risking behavior during the transition to middle school. Although an examination of intervention effects was not a focus of the present study, intervention condition was included as a control variable in the analyses. Interviewers were blind to the intervention status of the girls.

Study 2

Study 2 contained 264 girls who were entering secondary school and living in the United Kingdom at the time of recruitment (1999; M age = 11.65, SD = .48). The sample was derived from a three-year longitudinal community study of more than 500 parents, children (boys and girls), and teachers living in South and Mid-Wales on the effects of inter-parental conflict on children’s emotional, behavioral, and academic development. Participants were recruited through 12 schools across South Wales, with 83% of those in the catchment area consenting to participate. Parents were invited to participate by a letter explaining the project and were further informed of the aims of the research through presentations at scheduled parent-teacher evenings. The ethnic distribution of the girls was 98% European American, 1.5% Indian, Sri-Lankan, or Pakistani, and .5% non-British origin (East African, Jamaican). The majority of children lived in two-parent families (80.4%), including both biological and step-parent families. Analysis of demographic characteristics suggested that the overall sample was representative of British families living in England and Wales with respect to family composition, parent education, and ethnic representation (Office for National Statistics, 2002).

Procedures

In both studies, data were collected at three time points, each separated by a 12-month interval. Girls were approximately 11.5 years old at T1, 12.5 at T2, and 13.5 at T3. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Oregon Social Learning Center (Study 1) and Cardiff University (Study 2). Foster parent and caseworker consent (Study 1), parent/guardian consent (Study 2), and youth assent (Study 1 and 2) were obtained prior to study onset. In Study 1, data at each time point were collected from the foster parent and girl during a 2.5-hour home visit that included questionnaires and a structured interview. Girls were interviewed in a separate room from the parent to help ensure privacy and confidentiality of responses. In Study 2, data were collected from the parents via questionnaires received through the mail and from girls using questionnaires completed independently during the school day under the supervision of the researchers.

Measures

Child depressive symptoms

In Study 1, child-reported depressive symptoms were measured at T1, T2, and T3 using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CESD, Radloff, 1977). In Study 2, depressive symptoms were measured at T1, T2, and T3 with the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985; Study 2). The CESD is a 20-item self-report measure of depressive symptomatology with a typical clinical cutoff score of 16 or higher (Radloff, 1977). The CDI is a 26-item self-report measure of depressive symptomatology with a typical clinical cutoff score of 13 or higher (Kovacs, 1992). In the present study, the percent of girls at or above the clinical threshold for depressive symptoms was 30% (T1), 27% (T2), and 20% (T3) for Study 1 and 30% (T1), 28% (T2), and 35% (T3) for Study 2. Internal consistency in both studies was acceptable (α = .71–.78 Study 1; α = .82.86 Study 2).

Tobacco and alcohol use

Each study administered questions to the child about the frequency of her tobacco and her alcohol use at T1 and T3. In Study 1, girls provided their answers directly to the interviewer in a separate room away from the caregiver (e.g., ‘How many times have you drunk beer, wine, or hard liquor?’). In Study 2, girls self-reported their tobacco and alcohol use independently in a classroom setting on a paper-and-pencil questionnaire (e.g., ‘How often have you drunk beer, cider, or spirits (whisky, vodka, gin etc.)’). Because of the strong positive skew derived from relatively low rates of endorsement of use, alcohol and tobacco use were each recoded into dichotomous variables reflecting any use versus no use (1 = yes, 0 = no) at each time point. In Study 1, the recall period for participants was 6 months and in Study 2 the recall period was 12 months.

Aggression

The parent-report version of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991) was administered at T1 in both Study 1 and Study 2 to mothers/the female caregiver. The 18-item aggression subscale raw score was used to measure child aggression. Inter-item alphas were acceptable (α = .92 Study 1; α = .88 Study 2). Child aggression was included in the analytical models in order to control for the effects of co-occurring externalizing problems.

Analysis Plan

Latent growth curve analysis was used to examine the trajectory of depressive symptoms across both samples over the three time points (T1, T2, T3) considered in the present study (McArdle, 1988). In latent growth curve modeling, a regression curve is fit for each individual’s scores over time which yields growth parameters (e.g. intercept, slope coefficient; Duncan & Duncan, 2004). The mean and variance of these parameters can then be inspected at the group level. In a growth curve model, these parameters are represented as latent, or unobserved, factors. As two points can only represent a line, these factors are used to estimate the intercept and shape of growth from three or more time points. In addition, the information represented in the latent factors can be used to predict other variables as well.

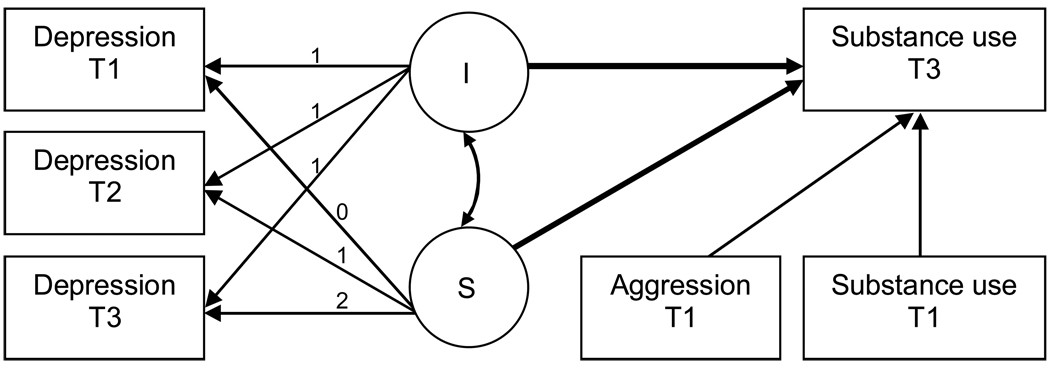

Data were analyzed using MPlus (Muthén & Muthén, 2004). A linear slope term was used and examined separately for Study 1 and Study 2. If the linear factor in the growth curve model and its associated variance term were not significant, an intercept only model was then tested; if the linear term was not significant, but significant variance in the linear term was found, then relative model fit (i.e., sample-size adjusted BIC) was used to determine whether the linear term should be retained, with lower scores indicating better fit. After determining the most representative model of depressive symptoms for each study, we examined whether the latent depression model parameters (i.e., intercept, linear slope term) predicted tobacco use and alcohol use at T3, when controlling for T1 tobacco/alcohol use and T1 mother-reported aggression (see Figure 1). In addition, for Study 1, intervention vs. control group membership was controlled (not shown in the figure). Indices of absolute fit (e.g., CFI, RMSEA) were not provided by MPlus due to the categorical outcome variables.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model for the effects of depressive symptoms on tobacco and alcohol use. I=intercept; S=slope. The paths of interest are represented as bold lines.

Since the outcome variables for tobacco and alcohol use were dichotomous (i.e., did or did not use tobacco/alcohol), this part of the analysis was conducted using logistic regression. The logistic regression model included the intercept and linear slope terms from the growth models as predictors of T3 alcohol and tobacco use while controlling for T1 alcohol, tobacco, and aggression (and T1 intervention condition in Study 1). The raw regression coefficients (log odds) are reported; when they were significant or evidencing a trend toward significance, the associated odds ratios (OR) are also reported. The odds ratio indicates the relative probability of belonging to one group (e.g., substance user) as opposed to another group (e.g., non-user). An odds ratio greater than one indicates an increased probability of substance use, while an odds ratio less than one indicates a decreased probability of substance use.

Missing data and the impact of the observed pattern of missingness on derived parameter estimates were examined within each sample. For example, Study 1 was missing alcohol and tobacco use data at T3 for 11 of 100 individuals (11%), and Study 2 was missing depression data at T3 for 52 of 264 individuals (19.7%). In both studies, data were Missing Completely At Random [Study 1: Little’s MCAR test, χ2(8) = 8.59, ns; Study 2: Little’s MCAR test, χ2(27) = 28.41, ns], indicating that the missing data did not introduce bias into the analyses. All analyses were performed using the available data but were subsequently replicated using multiple imputation techniques. Under multiple imputation, each missing data point is replaced with a set of plausible values that are imputed based upon the relationships found within the extant data (Schafer & Graham, 2002; Sinharay, Stern, & Russell, 2001). No differences were observed when the models were run with the available data versus the imputed data, and thus the non-imputed results are reported here.

Results

Means, standard deviations, sample sizes, and correlations for all study variables are presented in Table 1 (Study 1 in upper diagonal and Study 2 in lower diagonal). To test for potential differences between the two studies, linear regression models predicting mean differences between Study 1and Study 2 girls on T1 aggression, and logistic regression models predicting mean differences in T3 tobacco and alcohol use were conducted. Significant differences were found across study: mean levels of aggression were significantly higher for girls in Study 1 than Study 2 (b = −5.12, SE = .69, β = −.38, p < .001), while tobacco use (b = 1.14, SE = .20, OR = 3.12, p < .001) and alcohol use (b = 1.90, SE = .19, OR = 6.65, p < .001) were significantly higher for girls in Study 2 (i.e., belonging to Study 2 increased the likelihood of using tobacco and alcohol at T3). Because different measures of depressive symptoms were used in each study, mean level comparisons could not be made for depression. However, examination of the sample means relative to clinical cutoff scores for the two studies suggest fairly comparable levels of symptomatology, particularly at the first two time points (see comparisons presented in the Measures section).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Study Variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | M | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depression (T1) | - | .43*** | .36** | .17† | .16 | −.05 | .04 | .20† | 12.92 | 8.91 | 99 |

| 2. Depression (T2) | .62*** | - | .37** | .16 | .17 | −.01 | .17 | .24* | 12.51 | 8.53 | 97 |

| 3. Depression (T3) | .57*** | .68*** | - | −.16 | .22* | .11 | .28** | .19† | 11.60 | 8.65 | 89 |

| 4. Tobacco Use (T1) | .20** | .11† | .12† | - | .32** | −.02 | .26* | XX | .01 | - | 100 |

| 5. Tobacco Use (T3) | .18** | .20** | .24** | .42*** | - | −.06 | .60*** | −.06 | .10 | - | 89 |

| 6. Alcohol Use (T1) | .18** | .15* | .14* | .24*** | .30*** | - | .10 | −.07 | .04 | - | 100 |

| 7. Alcohol Use (T3) | .13† | .13† | .15* | .19** | .38*** | .35*** | - | −.21† | .15 | - | 89 |

| 8. Aggression (T1) | .22** | .28*** | .21** | .04 | .01 | .06 | −.01 | - | 10.23 | 7.83 | 93 |

| M | 9.51 | 9.58 | 10.74 | .16 | .45 | .46 | .80 | 5.10 | |||

| SD | 7.60 | 7.74 | 8.68 | - | - | - | - | 4.35 | |||

| N | 240 | 231 | 212 | 255 | 217 | 255 | 217 | 191 | |||

Note. Study 1 data are presented above the diagonal and in the upper half of the table. Study 2 data are presented below the diagonal and in the lower half of the table. Due to the slightly skewed nature of the depressive symptoms and aggression data, Spearman’s correlations are presented. Standard deviations not presented for dichotomous variables. XX = could not be calculated (no tobacco use in the subsample that had aggression data).

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

As evidenced from the correlations, there was moderate rank-order stability in depressive symptoms over time in both studies. In addition, T1 aggression was associated with depressive symptoms at all time points in both studies. In Study 1, T3 depressive symptoms were associated with T3 tobacco and T3 alcohol use, and alcohol and tobacco were generally associated with one another with the exception of T1 alcohol use. In Study 2, depressive symptoms, tobacco use, and alcohol use were associated with one another at all time points.

The first step in the latent growth curve analysis was to examine the growth curve model for depressive symptoms (see Table 2). The linear slope terms were not significant, but there was significant variability in each sample for the linear term; as a result, the linear terms were retained. Overall, both studies exhibited flat mean growth curves for depressive symptoms (i.e., no significant change over time), but each study demonstrated significant variability (.11, p < .001 for Study 1 and .10, p < .001 for Study 2), suggesting that different individuals experienced different levels of change in depressive symptoms over time. The covariance between the intercept and slope terms was r = −.51, p < .05 (Study 1) and r = −.33, p < .05 (Study 2), suggesting that girls who were lower on depressive symptoms at T1 showed the greatest increases over time. The adjusted BIC suggested that the linear terms should be retained in both models [Study 1: 2042.22 (with) vs. 2176.91 (without); Study 2: 4302.12 (with) vs. 4465.68 (without)].

Table 2.

Mean Growth Curves for Child Depressive Symptoms.

| Study 1 (N=100) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean | Variance | |

| Intercept | 2.41*** | .36*** |

| Linear Slope | −.05 | .11*** |

| Study 2 (N=264) | ||

| Mean | Variance | |

| Intercept | 1.99*** | .57*** |

| Linear Slope | .05 | .10*** |

p < .001.

Second, we examined the prediction of tobacco use and alcohol use at T3 from the intercept and slope terms derived in the growth curve models, controlling for T1 aggression and T1 substance use in both studies and intervention condition in Study 1. Both the intercept (b = .15, p < .05) and slope (b = .33, p < .05) for depressive symptoms were significant predictors of tobacco use in Study 1 (see Table 3). The OR suggested that individuals with higher initial levels of depressive symptoms and those who showed greater increases in depressive symptoms over time had increased odds of using tobacco at T3. From a practice standpoint, tobacco use at T1 was nonexistent (1 case in 100) in Study 1, and including this term in the model compromised model estimation; therefore, it was not retained as part of the specified model. Aggression at T1 and the intervention condition were not significant predictors.

Table 3.

Logistic Regressions Predicting Tobacco and Alcohol Use from Depressive Symptoms.

| Study 1 (N=100) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | (SE) | Odds (95% CI) | ||

| Tobaccoa | Intercept | .15* | (.06) | 1.16 (1.03 – 1.30) |

| Linear Slope | .33* | (.14) | 1.40 (1.05 – 1.85) | |

| Intervention | −.03 | (.06) | - | |

| Aggression | .00 | (.00) | - | |

| Alcohol | Intercept | .18* | (.08) | 1.20 (1.03 – 1.39) |

| Linear Slope | .61*** | (.17) | 1.84 (1.32 – 2.53) | |

| Alcohol (T1) | .09 | (.19) | - | |

| Intervention | −.06 | (.06) | - | |

| Aggression | −.01* | (.01) | .99 (.98 – .99) | |

| Study 2 (N=264) | ||||

| b | (SE) | Odds (95% CI) | ||

| Tobacco | Intercept | .10* | (.05) | 1.10 (1.01 – 1.21) |

| Linear Slope | .33* | (.13) | 1.40 (1.07 – 1.80) | |

| Tobacco (T1) | .58*** | (.06) | 1.78 (1.58 – 2.01) | |

| Aggression | .00 | (.01) | - | |

| Alcohol | Intercept | .09† | (.05) | 1.09 (1.00 – 1.20) |

| Linear Slope | .12 | (.12) | - | |

| Alcohol (T1) | .29*** | (.06) | 1.34 (1.20 – 1.50) | |

| Aggression | −.01 | (.01) | - | |

As described in the text, T1 tobacco use was not included as a predictor in Study 1 due to a lack of endorsement.

p < .06.

p < .05.

p < .001.

When predicting alcohol use in Study 1, both the intercept (b = .18, p < .05) and slope (b = .61, p < .001) for depressive symptoms were significant predictors, with the OR again suggesting that individuals with higher initial levels of depressive symptoms and greater increases in depressive symptoms were more likely to use alcohol at T3. Earlier alcohol use and the intervention condition were not significant, but aggression was a significant negative predictor (b = −.01, p < .05), suggesting that higher levels of aggression at T1 were associated with a reduced propensity to alcohol use at T3.

In Study 2, both the intercept (b = .10, p < .05) and slope (b = .33, p < .05) for depressive symptoms were significant when predicting tobacco use. Similar to the findings in Study 1, the OR suggested that individuals with higher initial levels of depressive symptoms and who showed greater increases in depressive symptoms over time had increased odds of using tobacco at T3. T1 tobacco use was a significant predictor (b = .58, p < .001), but aggression was not. When predicting alcohol use, the intercept term was marginally significant (b = .09, p < .06) and the slope was non-significant (p > .10). T1 alcohol use was a significant predictor (b = .29, p < .001), but aggression was not.

Discussion

The present analyses suggested that individual variation in depressive symptoms across early adolescence (from age 11.5 to age 13.5) predicted girls’ tobacco use in both samples and alcohol use in the foster care sample only at age 13.5. Girls with higher levels of depressive symptoms at age 11.5 and girls with increasing levels of depressive symptoms across early adolescence were at heightened risk of engaging in substance use at age 13.5, consistent with the study hypotheses. The two studies indicated comparable levels of increased risk for tobacco use, with the OR ranging from 1.10 – 1.16 for the intercept factor and at 1.40 for both studies for the slope factor, suggesting a greater risk for tobacco use among girls with increased depressive trajectories. The high degree of replication of the tobacco use findings across the two samples is notable, particularly given the significant differences in the base rates of tobacco use across the two studies (higher in the UK sample) and the community versus foster care nature of the two samples. The robustness of the effect suggests a potential utility in identifying girls who show elevated levels of depressive symptoms during the transition to secondary or middle school for participation in programs focused on the prevention of tobacco use.

The results partially supported the hypotheses for alcohol use, with significant associations between trajectories of depressive symptoms and alcohol use among girls in the US-based foster care study, but not among girls in the UK community sample. For the US foster girls, initial levels of depressive symptoms at age 11.5 and increases in depressive symptoms across early adolescence predicted an elevated likelihood of alcohol use at age 13.5. The odds ratio suggested a moderate-size magnitude of increased risk for alcohol use (1.84) for girls with increasing trajectories of depressive symptoms.

Because the two samples examined in the present study varied on multiple dimensions (e.g., country and sample type), we cannot discern which sample dimensions were responsible for the differences across studies in the associations between trajectories of depressive symptoms and subsequent alcohol use. Speculatively, associations between trajectories of depressive symptoms and alcohol use may not have been present in the UK sample because a large number of girls were already showing drinking behaviors at the start of the study (46%), as compared to the girls in the US sample (4%), and because the UK girls continued to show higher rates of alcohol use at T3 relative to the US girls (80% versus 15%). As noted earlier in this manuscript, alcohol consumption rates are somewhat higher in the UK for girls aged 11–15 than they are for similarly aged girls in the US (Bonomo & Proimos, 2005; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009a), thus, alcohol consumption may be viewed as a more normative early adolescent behavior in the UK and therefore less linked to psychopathologies such as depressive symptoms. A normative cultural difference between the two nations is observed in the national regulations around legal drinking age, with the legal drinking age set at 21 in the US and at 18 in the UK (and at 16 for consumption at a licensed bar or restaurant with a table meal).

Alternatively, the US girls’ maltreatment histories may have been a causal factor linking associations between trajectories of depressive symptoms and alcohol use within Study 1. Extant research suggests that maltreatment and a history of foster care are associated with substance use disorders (Pilowsky & Wu, 2006; Vaughn, Ollie, McMillen, Scott, & Munson, 2007), and depression may serve as a mediating mechanism of this association. Additional research is needed to examine these speculative hypotheses and the underlying mediating mechanisms.

Although prior studies have found that girls’ depressive symptoms increase across adolescence (Ge et al., 1994), and there was significant individual variability in the slope of depressive symptoms among girls in the current study, neither Study 1 nor Study 2 data showed a significant mean level increase in depressive symptoms from age 11.5 to age 13.5. It may be that the 2-year window of development examined in the present study didn’t fully capture the developmental period where the normative increase is typically seen, and that additional assessments later in development are needed to fully measure this effect (e.g., Natsuaki, Biehl, & Ge, 2009). Nonetheless, additional studies are needed to examine whether sample-specific features (e.g., foster care sample) were responsible for the mean level stability in depressive symptoms across the study period.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

In summary, the present study identified trajectories of depressive symptoms across early adolescence as increasing the risk for tobacco use among girls in a US-based foster care sample and among girls in a UK-based community sample. In addition, increasing trajectories of depressive symptoms heightened the risk for alcohol use in the foster girl sample. These results suggest the potential utility in targeting substance use prevention programs at girls who have elevated depressive symptoms during the transition to early adolescence. As reviewed earlier, substance use may serve as a coping mechanism or self-medication approach to treating depressive symptoms. As such, interventions focused on girls with depressive symptoms might employ intervention methods that improve coping skills, enhance social support networks, and employ cognitive behavioral therapy approaches to reduce depressive symptoms and prevent the onset of substance use. Extant research indicates that reductions in substance use and depression go hand in hand (Goldstein et al., 2009). As such, effective intervention and prevention programs should address these problems in the broader adolescent context in which they occur, including family interactions, adolescent stressors, social skills, and body image (Kumpfer et al., 2008). Strengths of the study include the dual-sample approach, the focus on the early adolescent period, the longitudinal analytical approach, and the inclusion of T1 aggression and T1 substance use as controls. These strengths notwithstanding, several limitations should be noted.

First, because of the low T1 rates of tobacco use in both studies and the low T1 rates of alcohol use in Study 1, we did not examine longitudinal bidirectional models. Bidirectional effects and/or reverse causality may have been present. For example, tobacco and alcohol use might lead to increases in depressive symptoms, as other studies of adolescents have shown (e.g., Gallerani et al., 2009; Silberg et al., 2003). However, Study 1 girls showed little to no substance use at T1, making an examination of the directionality of effects not feasible. Nonetheless, we controlled for initial levels of substance use in an effort to consider the bidirectionality of effects, and we highlight here the importance of examining directionality in future research.

Second, potential mediating factors such as pubertal timing, peer influences, and genetic influences could not be examined in the present study due to measurement constraints. Prior work suggests the importance of these factors in relation to depression and substance use (Marklein, Negriff, & Dorn, 2009; Natsuaki et al., 2009; Wiesner & Ittel, 2002). For example, a longitudinal study of adolescent twin pairs suggested that genetic factors played a significant role in the associations between girls’ depression and her tobacco use (Silberg et al, 2003). In contrast, this same study found that associations between girls’ depression and her alcohol use resulted from individual-specific environmental mechanisms. The differing etiologies of co-occurring depression and tobacco use in adolescent girls (significant shared genetic liability) versus co-occurring depression and alcohol use (individual environmental liability) provide some support for the speculation detailed above regarding a possible explanation of the differences across the US and the UK study in associations between depressive trajectories and alcohol consumption. Associations between depression and alcohol use may be more driven by environmental features specific to each country, whereas associations between depression and tobacco use may be more influenced by genetic influences, and as such, similar across individuals regardless of country of residence.

Third, the present study focused on early adolescent experimental levels of substance use rather than using a diagnostic assessment to examine substance use addictions and dependence. As such, caution is warranted in extending the findings beyond such contexts and drawing inferences about clinical-level behaviors and symptoms. In addition, we relied on girls’ self-reported use rather than collecting caregiver or peer ratings or using biomarker data. Although self-report is the most common method of assessment for youth in this age range (e.g., Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009a), it is conceivable that differences in the methods of assessment across the two studies may have led to girls under- or over-report their usage due to variation in privacy and social desirability (e.g., Study 1 girls reported their use during an interview whereas Study 2 girls recorded their use privately on a paper-pencil questionnaire). Further, the timeframe of use differed between the two studies (6-months in Study 1 and 12-months in Study 2) and have affected the increased prevalence rates in Study 2 as compared to Study 1. Nonetheless, the bivariate associations between depressive symptoms and tobacco use were very similar across studies. In conclusion, the present study extends the known association between girls’ substance use and depressive symptoms downward to the early adolescent developmental period, and suggests the utility in implementing tobacco use prevention programs for depressed girls prior to entry into secondary school.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work was provided by grant R01 MH054257, NIMH, U.S. PHS to Leslie Leve and by grant ERSC R000222569 from the Economic and Social Research Council to Gordon Harold. Additional support for the writing of this report was provided by the following grants: R01 DA024672 and P30 DA023920, NIDA, U.S. PHS, and R01 HD042608, NICHD, U.S. PHS.

Contributor Information

Leslie D. Leve, Oregon Social Learning Center, Eugene, OR, USA Center for Research to Practice, Eugene, OR, USA.

Gordon T. Harold, Centre for Research on Children and Families, University of Otago, NZ Department of Psychology, University of Otago, NZ.

Mark J. Van Ryzin, Oregon Social Learning Center, Eugene, OR, USA

Kit Elam, Centre for Research on Children and Families, University of Otago, NZ.

Patricia Chamberlain, Oregon Social Learning Center, Eugene, OR, USA; Center for Research to Practice, Eugene, OR, USA.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ. The epidemiology of disorders of conduct: nosological issues and comorbidity. In: Hill J, Maughan B, editors. Conduct disorders in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 126–168. [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Kassel JD. Adolescent smoking and depression: Evidence for self-medication and peer smoking mediation. Addiction. 2009;104:1743–1756. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, Chilcoat HD, Andreski P. Major depression and stages of smoking. A longitudinal investigation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;55:161–166. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EC, Catalano RF, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Abbott RD. Adolescent substance use outcomes in the raising healthy children project: A two-part latent growth curve analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:699–710. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomo Y, Proimos J. Substance misuse: alcohol, tobacco, inhalants, and other drugs. British Medical Journal. 2005;330:777–780. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7494.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Leve LD, Smith DK. Preventing behavior problems and health-risking behaviors in girls in foster care. International Journal of Behavioral and Consultation Therapy. 2006;2:518–530. doi: 10.1037/h0101004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colishaw S, Maughan B, Goodman R, Pickles A. Time trends in adolescent mental health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:1350–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC. An introduction to latent growth curve modelling. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:333–363. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Mental health, educational and social role outcomes of depressed adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;59:225–231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, Mason WA, Mazza JJ, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Latent growth modeling of the relationship between depressive symptoms and substance use during adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:186–197. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JS, Logan J, Wang G, Volkow ND. Monoamine oxidase and cigarette smoking. Neurotoxicology. 2003;24:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(02)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallerani CM, Garber J, Martin NC. The temporal relation between depression and comorbid psychopathology in adolescents at varied risk for depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02155.x. Online First. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Lorenz F, Conger R, Elder G, Simons R. Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:467–483. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Rende R, Boergers J, Abrams DB, Buka SL, Clark MA, et al. Parental smoking and adolescent smoking initiation: An intergenerational perspective on tobacco control. Pediatrics. 2009;123:274–281. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Shamseddeen W, Spirito A, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, et al. Substance use and the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:1182–1192. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181bef6e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE. Stress and symptoms of depression/anxiety among adolescents: Searching for mechanisms of risk. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:1015–1021. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Compas B. Unmasking unmasked depression in children and adolescents: The problem of comorbidity. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14:585–603. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Tsai W, Endicott J, Mueller TI, Coryell W, Keller M. Five-year course of major depression: Effects of comorbid alcoholism. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1996;41:63–70. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbell B, Anderson B, Bjarnason T, Ahlstronm S, Balakireva O, Kokkevi A, Morgan M. ESPAD Report, 2003: Alcohol and other drug use among students in 35 European countries. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JS, Mezulis AH, Abramson LY. The ABC’s of depression: Integrating affective, biological and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender depression. Psychological Review. 2008;115:291–313. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, MacLean CJ, Heath AC, Eaves LJ, Kessler RC. Smoking and major depression: a causal analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:36–43. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130038007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) New York: Multi-health Systems, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Smith P, Summerhays JF. A wake-up call to the prevention field: are prevention programs for substance use effective for girls? Substance Use and Misuse. 2008;43:978–1001. doi: 10.1080/10826080801914261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklein E, Negriff S, Dorn LD. Pubertal timing, friend smoking, and substance use in adolescent girls. Prevention Science. 2009;10:141–150. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0120-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Dynamic but structural equation modeling of repeated measures data. In: Cattell RB, Nesselroade J, editors. Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology. 2nd ed. New York: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 561–614. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Drake RE, Wallach MA. Dual diagnosis: a review of etiological theories. Addictive Behavior. 1998;23:717–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s Guide. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Centre for Social Research. Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England in 2008. NHS Information Centre. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Natsuaki MN, Biehl MC, Ge X. Trajectories of depressed mood from early adolescence to young adulthood: The effects of pubertal timing and adolescent dating. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19:47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Nellisery M, Feinn RS, Covault J, Gelernter J, Anton RF, Pettinati H, et al. Alleles of a functional serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism are associated with major depression in alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1402–1408. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000085588.11073.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. Social Trends 32. London: The Stationery Office; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Orton HD, Riggs PD, Libby AM. Prevalence and characteristics of depression and substance use in a U.S. child welfare sample. Children and Youth Service Review. 2009;31:649–653. [Google Scholar]

- Pietraszek MH, Urano T, Sumioshi K, Serizawa K, Takahashi S, Takada Y, et al. Alcohol-induced depression: Involvement of serotonin. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 1991;26:155–159. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a045096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Wu L. Psychiatric symptoms and substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample of American adolescents involved with foster care. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, La Greca AM. Childhood depressive symptoms and adolescent cigarette use: A six-year longitudinal study controlling for peer relations correlates. Health Psychology. 2009;28:283–291. doi: 10.1037/a0013949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Xing Y. Comorbidity of substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents: Evidence from an Epidemiologic survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88S:S4–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Chacko Y. Evaluation of a depression-related model of alcohol problems in 430 probands from the San Diego prospective study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;82:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberg J, Rutter M, D’Onofrio B, Eaves L. Genetic and environmental risk factors in adolescent substance use. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:664–676. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinharay S, Stern HS, Russell D. The use of multiple imputation for the analysis of missing data. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:317–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2009a. (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434) [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The NSDUH report: Trends in tobacco use among adolescent: 2002–2008. Rockville, MD: 2009b. Oct 15, Office of Applied Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn MG, Ollie M, McMillen JC, Scott LD, Munson MR. Substance use and abuse among older youth foster care. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1929–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Palacios G, Bonilla-Jaime H, Velazquez-Moctezuma J. Antidepressant effects of nicotine and fluoxetine in an animal model of depression induced by neonatal treatment with clomipramine. Progress in Neurolo-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2005;29:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner M, Ittel A. Relations of Pubertal Timing and Depressive Symptoms to Substance Use in Early Adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2002;22:5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm K, Wedgwood L, Niven H, Kay-Lambkin K. Smoking cessation and depression: current knowledge. Drug & Alcohol Review. 2006;25:97–107. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]