Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by the progressive loss of neurons and glial cells in the central nervous system correlated to their symptoms. Among these neurodegenerative diseases are Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Neurodegeneration is mostly restricted to specific neuronal populations: cholinergic neurons in AD and motoneurons in ALS. The demonstration that the onset and progression of neurodegenerative diseases in models of transgenic mice, in particular, is delayed or improved by the application of neurotrophic factors and derived peptides from neurotrophic factors has emphasized their importance in neurorestoration. A range of neurotrophic factors and growth peptide factors derived from activity-dependent neurotrophic factor/activity-dependent neuroprotective protein has been suggested to restore neuronal function, improve behavioral deficits and prolong the survival in animal models. In this review article, we focus on the role of trophic peptides in the improvement of AD and ALS. An understanding of the molecular pathways involved with trophic peptides in these neurodegenerative diseases may shed light on potential therapies.

Keywords: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, ADNF-9, NAP, Colivelin

INTRODUCTION

Neurodegenerative diseases are difficult to treat and are frequently incurable due to the complicated nature of the underlying mechanisms of neuronal cell death. Neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) result in a debilitating loss of memory and motor function, respectively. Although the mechanisms of action in neurodegenerative diseases are unclear, the potential underlying mechanisms can be divided into two categories. The first, unique to each neurodegenerative disease, is a trigger that initiates activation of cell death machinery. The second, which is thought to be universal among neurodegenerative diseases, is a directorial process to complete death of neurons [For review, see ref. [1]].

ALS is suggested to be related to a loss of motor neurons, progressively impairing the voluntary motor neuron system and resulting in motor paralysis. This is suggested to be caused by mutation of the superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1) gene, causing motoneuronal death [2]. Alternatively, neuronal loss in AD results in memory deficit. A widely accepted theory for the mechanism of AD is that Aβ is the primary factor for its neurotoxic effect [3–7].

Although there are currently no effective drugs for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, potential therapeutic targets for symptomatic treatments of neurodegenerative diseases may include neuroprotective factors, encompassing neurotrophins and neuroprotective peptides [8–10]. A deficit in the presence of endogenous neurotrophic factors may play a key role in the attenuation of the progression of neurodegenerative diseases [For review, see ref. [11]]. The types of neuroprotection demonstrated by neurotrophic factors include the prevention of oxidative stress that induces apoptosis, promotion of cell survival, and possible cell growth. Neurotrophic factors may improve cellular function and increase neuronal metabolism, which can even lead to restoration of synaptic connections by growth of new axons. Neurotrophic factors are categorized by their activity in preventing neuronal cell death [For review, see ref. [11]].

We focus in this review on NAP (NAPVSIPQ) peptide derived from activity neuroprotective protein and ADNF-9 peptide derived from activity-dependent neurotrophic factor (ADNF). Both NAP and ADNF-9 display activity in the femtomolar range, enhancing cell survival and outgrowth of dendrites in the form of D-acid analogues such as D-NAP and D-ADNF-9 [12, 13]. ADNF-9 and NAP peptides share functional and structural similarities, originally intended for use against β-amyloid peptides for reduction of toxicity and increased protection of neurons [14]. A novel hybrid peptide called colivelin was synthesized by the addition of ADNF-9 to the N-terminus of a humanin derivative. Colivelin has potential neuroprotecrive effect in some neurodegenerative diseases such as AD [15]. We discuss in this review article the two most prevalent neurodegenerative diseases: ALS and AD, including the mechanisms, current treatments, and implications of trophic peptides in treating neurodegenerative diseases.

OVERVIEW OF NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASES: ALS AND AD

Alzheimer’s disease

The most common neurodegenerative disease is AD, regularly known for its characteristic devastating memory and cognitive deficits. Neuronal cell death in the cortical area of the brain is believed to be related to the irreversible progression of dementia and cognitive disorders. The exact mechanism of action leading to AD is unknown, but there is a widely accepted theory regarding amyloid-β’s (Aβs) as the primary factor for its neurotoxic effect in AD pathology. In vivo experiments have shown that cell death may result from extreme concentrations of toxic Aβs [15–20]. Studies in both mice and human AD patients demonstrated that aggregation of the β-amyloid peptide has been found to form oligomers along the microtubules of neuroprocesses in the AD brain [14]. There also have been studies indicating that toxic Aβ concentrations of 1–25 μM or higher are the cause of neuronal cell death in vitro, supporting the Aβ cascade theory [2]. An in vitro study suggested that Aβ-related cell death is mediated by Aβ receptors as well as severe potential death-mediating receptors for toxic Aβ [2].

Alternatively, amyloid precursor protein (APP) has been suggested to play a major role in activation of a neuronal cell-death signaling cascade when TGFbeta2 binds as a natural ligand for APP [21, 22]. Hashimoto and colleagues found TGFbeta2 to also be down-regulated by administration of toxic Aβ. Aβ binds to the extracellular domain of APP in glial and neuronal cells, TGFbeta2 paracrinally and autonomically signaling the APP mediated cells. β-amyloid accumulation has been suggested to occur prior to Tau hyperphosphorylation, suggesting a possible cause and effect between accumulation and hyperphosphorylation [14]. At the present time, the FDA has approved acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA-type glutamate receptor antagonists for the treatment of moderate to severe AD [For review, see ref. [23]]. Currently there are no FDA approved treatments for behavioral and psychotic symptoms exclusive to AD, but many medications are used “off-label”. Semagacestat, a γ-secretase inhibitor, is currently being studied under two Phase III clinical trials for the treatment of AD [24]. Semagacestat is thought to lower levels of Aβ in the brain by blocking cleavage of membrane-bound β-amyloid precursor proteins via γ-secretase, as seen in studies using transgenic mice [25, 26]. In addition, studies have been conducted to investigate the role of Aβ, tau proteins, and insulin on the onset and progression of AD [27–29]

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is another neurodegenerative disease affecting the motor neurons, brainstem, and spinal cord. ALS is more commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Degeneration of motor neurons leads to characterized progressive loss of motor control, eventually leading to muscular dystrophy, motor paralysis, and death due to respiratory failure. Most cases of ALS are sporadic in occurrence, but about 10% of cases are familial [30]. Both forms share similar characteristics, and onset occurs typically in adulthood [31], although juvenile onset ALS has been reported as an autosomal recessive mutation in ALS2.

The initial trigger for onset of this multifactorial disorder is still unknown. However, several factors may lead to motor neuron degeneration, including mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, protein aggregation, protein misfolding, neuro-inflammation, cytoskeleton abnormalities, defective axonal transport, dysfunctional growth factor signaling, and excitotoxicity [30–32]. Mitochondrial abnormalities occur early in ALS pathogenesis; mutant SOD1 was found to be associated with mitochondria in the intermembrane space, possibly triggering apoptosis [33]. SOD inclusion formation may recruit proapoptotic BAX to mitochondria. A possible non-cell autonomous process characterized in ALS is inflammation, which appears in microglial and astroglial cells, resulting in mitochondrial damage and apoptosis [34–36]. Protein misfolding and aggregation mechanisms are still unclear, but protein inclusions have been found in human ALS, including ubiquitinated skein-like inclusion, bunina bodies, and hyaline inclusions rich in neurofilament proteins [37]. Alternatively, patients with mutant SOD1 have shown decreased levels of excitatory amino acid transporters (EAAT2), causing a decreased removal of glutamate from the synapse as well as increased glutamate in the cerebrospinal fluid [38, 39].

Based on studies performed in transgenic mice, mutations on the SOD1 gene lead to the familial form of ALS [2, 15]. In SOD1 transgenic mice, evidence of dynein defects related to dynein-mediated axonal transport processes have been reported to be the earliest pathologies in ALS. Neurons are very sensitive to dynein dysfunction, as dynein is highly expressed in neurons; this may suggest the vulnerability of the motor neurons (For review, see ref.[30]). Mutations in the SOD1 gene are thought to lead to a toxic gain of function, as opposed to a loss of function found in other neurodegenerative diseases [40]. Other studies suggest that angiogenic activity plays a critical role in the development of ALS. Mutations in ALS patients may be associated with functional loss of angiogenic activity and null mutations in progranulin, an angiogenic protein [31].

Currently, riluzole is the only prescribed treatment for ALS, but it only provides moderate survival in patients. Riluzole was initially investigated as an antiseizure drug and was later found to have neuroprotective properties [41]. Among other drugs, ceftriaxone a β-lactam antibiotic known to upregulate glutamate transporter 1 (GLT1), or EAAT2, and dexpramipexole are currently in Phase III clinical trials in ALS patients [42, 43].

ROLE OF NEUROTROPHIC DERIVED PEPTIDES IN ALS AND AD

NAP peptide derived from activity-dependent neuroprotective protein in ALS and AD

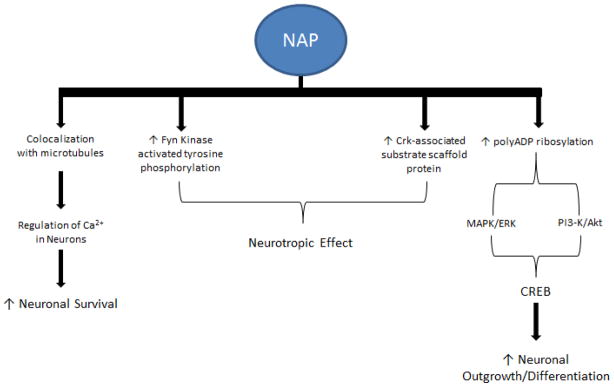

The parent protein, ADNP, is essential for brain development; it is found in the nuclei, cytoplasm, and occasionally along cytoplasmic microtubules [44, 45]. In vitro studies showed that recombinant ADNP was found to protect neurons against severe oxidative stress [46]. NAP mimics the neuroprotective activity of ADNP in its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, interact with tubulin, enhance assembly of microtubules, and promote neuronal outgrowth [44, 47, 48]. The specific association of NAP with tubulin was detected by fluorescent NAD distribution at the cellular level in cells that express neuron-specific βIII-tubulin as well as astrocyte tubulin, which does not express βIII-tubulin [14, 44, 49]. It is demonstrated that NAP colocalizes with microtubules, which regulate Ca2+ signaling in neurons (Figure 1) [44, 50, 51+. NAP’s association with Ca2+ mobilization may contribute to neuronal survival. Changes in mitochondrial Ca2+ homoestasis were found to be correlated with life-death pathways of cells in microtubule formation [49]. Other studies suggest that NAP is regulated by polyADP-ribosylation (Figure 1) [50] or that NAP stimulates the MAPK/ERK and PI3-K/Akt pathways [52]. Pascual and colleagues found that stimulation of MAPK/ERK and PI3-K/Akt leads to the phosphorylation of the transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), which produces neuronal outgrowth and differentiation (Figure 1). NAP protection and adaptation to enhance cognitive function can possibly be attributed to protection against apoptosis as a result of microtubule loss.

Figure 1.

Diagram shows several pathways involving NAP neuroprotection. Among these pathways, NAP can co-localize with microtubules to regulate neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis to increase neuronal survival. The neuroprotective effect of NAP, mediated by increases in Fyn kinase, activated tyrosine phosphorylation and the level of Crk-associated substrate scaffold protein. Alternatively, increases in neuronal outgrowth and differentiation might be mediated through CREB involving MAPK/ERK and PI3-K/Akt pathways, which are activated by increased polyADP ribosylation.

Studies regarding a mouse model for AD have shown deregulation of ADNP expression in the hippocampus [53]. Tau mutants have decreased affinity to microtubules, leading to less protection and aggregation of tau. NAP’s neurotrophic effect lies in the activation of Fyn Kinase activated tyrosine phosphorylation and Crk-associated substrate (Cas) scaffold protein (Figure 1) [14]. NAP treatment is also associated with chromatin remodeling and neurite outgrowth due to enhanced poly-ADP ribosylation, connected with ADNP signaling (Figure 1) [44, 48–50]. While protecting against neurotoxins, NAP does not affect cell division [54]. In addition, studies have found that treatment with NAP in ADNP knockdown mice resulted in enhanced cognition and improved associated deficiencies [48]. Positive study results and clean toxicity reports have landed NAP in phase II clinical trials with a primary focus on AD-related cognitive impairment [14]. Studies are also being conducted to evaluate the effects of NAP in ALS models associated with cytoskeletal dysfunction. NAP extended life span in ALS mouse models when administered prior to disease onset, protecting against tauopathy [55].

ADNF-9 peptide derived from activity-dependent neurotrophic factor in AD and ALS

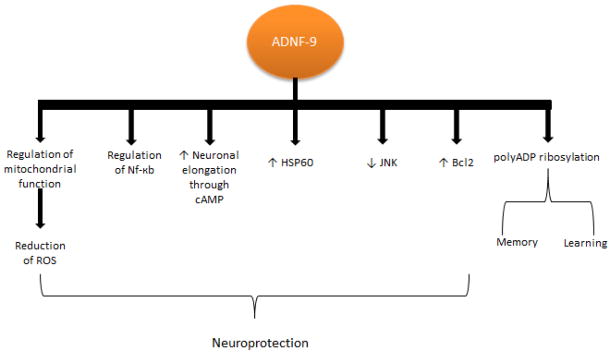

ADNF is a glial neurotrophic protein factor and, along with ADNP, it is released in response to vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) that protects neurons from tetrodoxin-induced cell death by electrical blockade as well as related insults from AD and ALS. ADNF is suggested to be essential for neuronal survival and embryonic growth regulated by VIP [56–61]. ADNF-9 derived from ADNF, also known as SAL (SALLRSIPA), is the active core of its parent compound and mimics its neuroprotective activity [56, 57]. In AD, ADNF-9 has been found to protect against Aβ, apolipoprotein E deficiencies, and oxidative insults, as well as enhancing synapse formation [56, 62–64]. It is noteworthy that ADNF-9 showed a greater prevention of cell death associated with stress than did other ADNF derived peptides such as ADNF-14, which also protects against cell death [56] and provides neuroprotection against AD-related toxicity [57, 65]. ADNF-9 protects against Aβ peptide and oxidative stress through regulation of mitochondrial function, reduction of accumulating reactive oxygen species, and regulation of the Nf-kb transcription factor (Figure 2) [62, 66]. Moreover, ADNF-9 also promotes axonal elongation through cAMP-dependent mechanisms and increases chaperonin expression of heat shock protein 60, which leads to neuroprotection against Aβ insult (Figure 2) [66–68]. In vitro studies using both hippocampal and cortical neurons demonstrated that ADNF-9 stimulates synapse formation [69]. ADNF-9 was also shown to have an effect on memory and learning in association with polyADP ribosylation catalyzed by poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1 (Figure 2) [50]. Other possible mechanisms of neuroprotection include the Bcl2 mitochondrial intrinsic signaling pathway, which regulates cell survival and apoptosis [70] and the extrinsic JNK signaling pathway [71]. The all D-amino acid analogue of ADNF-9 was found to protect against Aβ tau hyperphosphorylation, in early events, in vitro and in vivo, with regards to neuroprotection and maintenance of neuronal organization [72]. ADNF-9 was tested in in vitro and in vivo ALS models [58]. This study demonstrated that ADNF-9 suppressed SOD-1-mediated cell death. The neuroprotective effect of ADNF-9 involves CaMKIV and tyrosine kinase signaling pathways. Neuroprotection is thought to occur as a result of CaMKIV and tyrosine kinase involvement when ADNF is administered intracerebroventricularly. Although prolonged survival of the ALS mouse model was marginal, it did provide insight into a possible treatment for ALS.

Figure 2.

Diagram shows several pathways involving ADNF-9 neuroprotection. Among these pathways, ADNF-9 regulates mitochondrial function and NF-kB, increases neuronal elongation, decreases HSP60, decreases JNK, and increases Bcl2. ADNF-9 ameliorates learning and memory through polyADP ribosylation.

Colivelin, hydrbrid synthetic peptide of ANDF-9 and Humanin, in AD and ALS

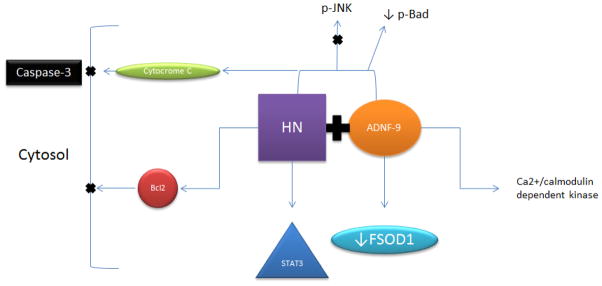

Neuroprotective peptide colivelin was created by adding ADNF-9 to the N-terminus of the humanin peptide [2, 73]. Humanin was identified as an endogenous neuroprotective peptide, which is suggested to protect against AD-related toxicity and cytotoxicity as a result of various stimuli [1, 74]. Moreover, studies have shown that humanin suppresses neurotoxicity through extracellular cell surface receptors, which induce cytoprotective signals [74, 75]. It is suggested that humanin interacts with the Bcl-2 family of proapoptotic proteins, blocking their action in the cytosol (Figure 3) [74, 76, 77]. Although the mechanisms of action of colivelin in neuroprotection are unclear, two independent prosurvival signals have been suggested: a humanin mediated STAT3 pathway and ADNF-9 mediated Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV pathway (Figure 3) [73]. It is noteworthy that ADNF-9 is active in the femtomolar concentration range, but activity is lost by about 10 nM, whereas humanin analogue AGA(C8R)HNG17 is active starting at 10 pM [56–58, 73].

Figure 3.

Diagram shows pathways involved in colivelin neuroprotection. Colivelin neuroprotection is mediated through Bcl2, cytochrome c and caspase-3 pathways. In addition, colivelin neuroprotection may involve STAT3, JNK and Bad pathways. It is suggested that ADNF-9 fragment of colivelin involves Ca2+/calmodulin dependent kinase.

Colivelin is active in the femtomolar range and does not lose activity at higher concentrations [73]. Humanin was found to provide neuroprotection against AD-related insults such as Aβ neurotoxicity [75]. The JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway showed importance in colivelin neuroprotection against AD-related memory loss [78–80]. An in vivo study found that colivelin has more potent neuroprotective effects than humanin and ADNF-9 have when tested against Aβ neurotoxicity [73].

Although, ADNF-9 was found to suppress the FSOD1 ALS-related gene [58], colivelin was found to be more neuroprotective than ADNF-9 in this model. Colivelin neuroprotection was associated with motor performance improvement but not increased lifespan in the ALS mouse model of SOD1 [58]. Moreover, another study showed that colivelin improved motor performance and increased lifespan when compared to FSOD1, in addition to suppressing motoneuronal death [15].

CONCLUSION

The roles of neurotrophic factors and peptides are coming into focus for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and ALS. We discussed the potential application of neurotrophic peptides derived from ADNF and ADNP on the attenuation of the progression of ALS and AD. It is noteworthy that NAP is in Phase II clinical trials for the treatment of AD. ADNF-9 shows potential therapeutic effects in animal models of ALS. In addition, the hybrid peptide, colivelin, has been shown to be effective in animal models of ALS. In contrast to neurotrophic factors, these trophic peptides have the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier for efficacy. Ample evidence suggests that these trophic peptides have potential for the treatment of ALS and AD.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the National Institutes of Health-NIAA for their continuous support (R21AA017735; R21AA016115). We would also like to thank Charisse Montgomery for editing this review article.

Footnotes

ROSS Open Access articles will be distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work will always be cited properly.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None

References

- 1.Chiba T, Nishimoto I, Aiso S, Matsuoka M. Neuroprotection against neurodegenerative diseases: development of a novel hybrid neuroprotective peptide Colivelin. Mol Neurobiol. 2007;35:55–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuoka M, Hashimoto Y, Aiso S, Nishimoto I. Humanin and colivelin: neuronal-death-suppressing peptides for Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. CNS Drug Rev. 2006;12:113–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer’s disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;120:885–90. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Müller-Hill B. The precursor of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature. 1987;325:733–6. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goate A, Chartier-Harlin MC, Mullan M, Brown J, Crawford F, Fidani L, Giuffra L, Haynes A, Irving N, James L, et al. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1991;349:704–6. doi: 10.1038/349704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawasumi M, Hashimoto Y, Chiba T, Kanekura K, Yamagishi Y, Ishizaka M, Tajima H, Niikura T, Nishimoto I. Molecular mechanisms for neuronal cell death by Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein-relevant insults. Neurosignals. 2002;11:236–50. doi: 10.1159/000067424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawasumi M, Chiba T, Yamada M, Miyamae-Kaneko M, Matsuoka M, Nakahara J, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T, Kato S, Aiso S, Nishimoto I, Kouyama K. Targeted introduction of V642I mutation in amyloid precursor protein gene causes functional abnormality resembling early stage of Alzheimer’s disease in aged mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2826–38. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu B, Pang PT, Woo NH. The yin and yang of neurotrophin action. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:603–14. doi: 10.1038/nrn1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hefti F, Mash DC. Localization of nerve growth factor receptors in the normal human brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1989;10:75–87. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(89)80014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chao MV, Rajagopal R, Lee FS. Neurotrophin signalling in health and disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;110:167–73. doi: 10.1042/CS20050163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sari Y. Potential drugs and methods for preventing or delaying the progression of Huntington’s disease. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov. 2011;6:80–90. doi: 10.2174/157488911795933884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gozes I, Divinski I, Piltzer I. NAP and D-SAL: neuroprotection against the beta amyloid peptide (1-42) BMC Neurosci. 2008;9 (Suppl 3):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-S3-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagrèze WA, Pielen A, Steingart R, Schlunck G, Hofmann HD, Gozes I, Kirsch M. The peptides ADNF-9 and NAP increase survival and neurite outgrowth of rat retinal ganglion cells in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:933–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gozes I. NAP (davunetide) provides functional and structural neuroprotection. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:1040–4. doi: 10.2174/138161211795589373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiba T, Yamada M, Sasabe J, Terashita K, Aiso S, Matsuoka M, Nishimoto I. Colivelin prolongs survival of an ALS model mouse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:793–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao B, Chrest FJ, Horton WE, Jr, Sisodia SS, Kusiak JW. Expression of mutant amyloid precursor proteins induces apoptosis in PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res. 1997;47:253–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sudo H, Hashimoto Y, Niikura T, Shao Z, Yasukawa T, Ito Y, Yamada M, Hata M, Hiraki T, Kawasumi M, Kouyama K, Nishimoto I. Secreted Abeta does not mediate neurotoxicity by antibody-stimulated amyloid precursor protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:548–56. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashimoto Y, Kaneko Y, Tsukamoto E, Frankowski H, Kouyama K, Kita Y, Niikura T, Aiso S, Bredesen DE, Matsuoka M, Nishimoto I. Molecular characterization of neurohybrid cell death induced by Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta peptides via p75NTR/PLAIDD. J Neurochem. 2004;90:549–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto Y, Niikura T, Tajima H, Yasukawa T, Sudo H, Ito Y, Kita Y, Kawasumi M, Kouyama K, Doyu M, Sobue G, Koide T, Tsuji S, Lang J, Kurokawa K, Nishimoto I. A rescue factor abolishing neuronal cell death by a wide spectrum of familial Alzheimer’s disease genes and Abeta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6336–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101133498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giovanni A, Wirtz-Brugger F, Keramaris E, Slack R, Park DS. Involvement of cell cycle elements, cyclin-dependent kinases, pRb, and E2F x DP, in B-amyloid-induced neuronal death. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19011–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashimoto Y, Chiba T, Yamada M, Nawa M, Kanekura K, Suzuki H, Terashita K, Aiso S, Nishimoto I, Matsuoka M. Transforming growth factor beta2 is a neuronal death-inducing ligand for amyloid-beta precursor protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9304–17. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9304-9317.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashimoto Y, Nawa M, Chiba T, Aiso S, Nishimoto I, Matsuoka M. Transforming growth factor beta2 autocrinally mediates neuronal cell death induced by amyloid-beta. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:1039–47. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cummings JL. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:56–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopkins CR. ACS Chemical Neuroscience Molecule Spotlight on Semagacestat (LY450139) ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1:533–4. doi: 10.1021/cn1000606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, Shankar GM, Kuskowski MA, Selkoe DJ, Ashe KH. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-beta protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elvang AB, Volbracht C, Pedersen LØ, Jensen KG, Karlsson JJ, Larsen SA, Mørk A, Stensbøl TB, Bastlund JF. Differential effects of gamma-secretase and BACE1 inhibition on brain Abeta levels in vitro and in vivo. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1377–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karczewska-Kupczewska M, Lelental N, Adamska A, Nikołajuk A, Kowalska I, Górska M, Zimmermann R, Kornhuber J, Strączkowski M, Lewczuk P. The influence of insulin infusion on the metabolism of amyloid beta peptides in plasma. Alzheimers Dement. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Zhou B, Deng B, Zhang F, Wu J, Wang Y, Le Y, Zhai Q. Amyloid-beta Induces Hepatic Insulin Resistance in vivo via JAK2. Diabetes. 2013;62:1159–66. doi: 10.2337/db12-0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomi M, Zhao Y, Thamotharan S, Shin BC, Devaskar SU. Early life nutrient restriction impairs blood-brain metabolic profile and neurobehavior predisposing to Alzheimer’s disease with aging. Brain Res. 2013;1495:61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soo KY, Farg M, Atkin JD. Molecular motor proteins and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:9057–82. doi: 10.3390/ijms12129057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Padhi AK, Kumar H, Vasaikar SV, Jayaram B, Gomes J. Mechanisms of loss of functions of human angiogenin variants implicated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, Donaldson D, Goto J, O’Regan JP, Deng HX, et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;362:59–62. doi: 10.1038/362059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okado-Matsumoto A, Fridovich I. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a proposed mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9010–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132260399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Den Bosch L, Robberecht W. Crosstalk between astrocytes and motor neurons: what is the message? Exp Neurol. 2008;211:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neusch C, Bähr M, Schneider-Gold C. Glia cells in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: new clues to understanding an old disease? Muscle Nerve. 2007;35:712–24. doi: 10.1002/mus.20768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henkel JS, Beers DR, Siklós L, Appel SH. The chemokine MCP-1 and the dendritic and myeloid cells it attracts are increased in the mSOD1 mouse model of ALS. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:427–37. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood JD, Beaujeux TP, Shaw PJ. Protein aggregation in motor neurone disorders. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003;29:529–45. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2003.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothstein JD, Van Kammen M, Levey AI, Martin LJ, Kuncl RW. Selective loss of glial glutamate transporter GLT-1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:73–84. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spreux-Varoquaux O, Bensimon G, Lacomblez L, Salachas F, Pradat PF, Le Forestier N, Marouan A, Dib M, Meininger V. Glutamate levels in cerebrospinal fluid in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a reappraisal using a new HPLC method with coulometric detection in a large cohort of patients. J Neurol Sci. 2002;193:73–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00661-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaw PJ. Molecular and cellular pathways of neurodegeneration in motor neurone disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1046–57. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.048652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellingham MC. A review of the neural mechanisms of action and clinical efficiency of riluzole in treating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: what have we learned in the last decade? CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17:4–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2009.00116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothstein JD, Patel S, Regan MR, Haenggeli C, Huang YH, Bergles DE, Jin L, Dykes Hoberg M, Vidensky S, Chung DS, Toan SV, Bruijn LI, Su ZZ, Gupta P, Fisher PB. Beta-lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature. 2005;433:73–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gibson SB, Bromberg MB. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug therapy from the bench to the bedside. Semin Neurol. 2012;32:173–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1329193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Divinski I, Mittelman L, Gozes I. A femtomolar acting octapeptide interacts with tubulin and protects astrocytes against zinc intoxication. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28531–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pinhasov A, Mandel S, Torchinsky A, Giladi E, Pittel Z, Goldsweig AM, Servoss SJ, Brenneman DE, Gozes I. Activity-dependent neuroprotective protein: a novel gene essential for brain formation. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;144:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(03)00162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steingart RA, Gozes I. Recombinant activity-dependent neuroprotective protein protects cells against oxidative stress. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;252:148–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gozes I, Zaltzman R, Hauser J, Brenneman DE, Shohami E, Hill JM. The expression of activity-dependent neuroprotective protein (ADNP) is regulated by brain damage and treatment of mice with the ADNP derived peptide, NAP, reduces the severity of traumatic head injury. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2005;2:149–53. doi: 10.2174/1567205053585873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vulih-Shultzman I, Pinhasov A, Mandel S, Grigoriadis N, Touloumi O, Pittel Z, Gozes I. Activity-dependent neuroprotective protein snippet NAP reduces tau hyperphosphorylation and enhances learning in a novel transgenic mouse model. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323:438–49. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.129551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Divinski I, Holtser-Cochav M, Vulih-Schultzman I, Steingart RA, Gozes I. Peptide neuroprotection through specific interaction with brain tubulin. J Neurochem. 2006;98:973–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Visochek L, Steingart RA, Vulih-Shultzman I, Klein R, Priel E, Gozes I, Cohen-Armon M. PolyADP-ribosylation is involved in neurotrophic activity. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7420–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0333-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mironov SL, Ivannikov MV, Johansson M. [Ca2+]i signaling between mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum in neurons is regulated by microtubules. From mitochondrial permeability transition pore to Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:715–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pascual M, Guerri C. The peptide NAP promotes neuronal growth and differentiation through extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase and Akt pathways, and protects neurons co-cultured with astrocytes damaged by ethanol. J Neurochem. 2007;103:557–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fernandez-Montesinos R, Torres M, Baglietto-Vargas D, Gutierrez A, Gozes I, Vitorica J, Pozo D. Activity-dependent neuroprotective protein (ADNP) expression in the amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2010;41:114–20. doi: 10.1007/s12031-009-9300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gozes I, Divinsky I, Pilzer I, Fridkin M, Brenneman DE, Spier AD. From vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) through activity-dependent neuroprotective protein (ADNP) to NAP: a view of neuroprotection and cell division. J Mol Neurosci. 2003;20:315–22. doi: 10.1385/JMN:20:3:315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jouroukhin Y, Ostritsky R, Gozes I. D-NAP prophylactic treatment in the SOD mutant mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: review of discovery and treatment of tauopathy. J Mol Neurosci. 2012;48:597–602. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9882-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brenneman DE, Gozes I. A femtomolar-acting neuroprotective peptide. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2299–307. doi: 10.1172/JCI118672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brenneman DE, Hauser J, Neale E, Rubinraut S, Fridkin M, Davidson A, Gozes I. Activity-dependent neurotrophic factor: structure-activity relationships of femtomolar-acting peptides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:619–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chiba T, Hashimoto Y, Tajima H, Yamada M, Kato R, Niikura T, Terashita K, Schulman H, Aiso S, Kita Y, Matsuoka M, Nishimoto I. Neuroprotective effect of activity-dependent neurotrophic factor against toxicity from familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutant SOD1 in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:542–52. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gozes I, Brenneman DE. A new concept in the pharmacology of neuroprotection. J Mol Neurosci. 2000;14:61–8. doi: 10.1385/JMN:14:1-2:061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Furman S, Steingart RA, Mandel S, Hauser JM, Brenneman DE, Gozes I. Subcellular localization and secretion of activity-dependent neuroprotective protein in astrocytes. Neuron Glia Biol. 2004;1:193–9. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X05000013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hill JM, Glazner GW, Lee SJ, Gozes I, Gressens P, Brenneman DE. Vasoactive intestinal peptide regulates embryonic growth through the action of activity-dependent neurotrophic factor. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;897:92–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glazner GW, Boland A, Dresse AE, Brenneman DE, Gozes I, Mattson MP. Activity-dependent neurotrophic factor peptide (ADNF9) protects neurons against oxidative stress-induced death. J Neurochem. 1999;73:2341–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0732341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blondel O, Collin C, McCarran WJ, Zhu S, Zamostiano R, Gozes I, Brenneman DE, McKay RD. A glia-derived signal regulating neuronal differentiation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8012–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08012.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bassan M, Zamostiano R, Davidson A, Pinhasov A, Giladi E, Perl O, Bassan H, Blat C, Gibney G, Glazner G, Brenneman DE, Gozes I. Complete sequence of a novel protein containing a femtomolar-activity-dependent neuroprotective peptide. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1283–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0721283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gozes I, Bassan M, Zamostiano R, Pinhasov A, Davidson A, Giladi E, Perl O, Glazner GW, Brenneman DE. A novel signaling molecule for neuropeptide action: activity-dependent neuroprotective protein. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;897:125–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Glazner GW, Camandola S, Mattson MP. Nuclear factor-kappaB mediates the cell survival-promoting action of activity-dependent neurotrophic factor peptide-9. J Neurochem. 2000;75:101–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.White DM, Walker S, Brenneman DE, Gozes I. CREB contributes to the increased neurite outgrowth of sensory neurons induced by vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and activity-dependent neurotrophic factor. Brain Res. 2000;868:31–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zamostiano R, Pinhasov A, Bassan M, Perl O, Steingart RA, Atlas R, Brenneman DE, Gozes I. A femtomolar-acting neuroprotective peptide induces increased levels of heat shock protein 60 in rat cortical neurons: a potential neuroprotective mechanism. Neurosci Lett. 1999;264:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith-Swintosky VL, Gozes I, Brenneman DE, D’Andrea MR, Plata-Salaman CR. Activity-dependent neurotrophic factor-9 and NAP promote neurite outgrowth in rat hippocampal and cortical cultures. J Mol Neurosci. 2005;25:225–38. doi: 10.1385/JMN:25:3:225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cory S, Adams JM. The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:647–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sari Y, Weedman JM, Ge S. Activity-dependent neurotrophic factor-derived peptide prevents alcohol-induced apoptosis, in part, through Bcl2 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling pathways in fetal brain of C57BL/6 mouse. Neuroscience. 2012;202:465–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shiryaev N, Pikman R, Giladi E, Gozes I. Protection against tauopathy by the drug candidates NAP (davunetide) and D-SAL: biochemical, cellular and behavioral aspects. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:2603–12. doi: 10.2174/138161211797416093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chiba T, Yamada M, Hashimoto Y, Sato M, Sasabe J, Kita Y, Terashita K, Aiso S, Nishimoto I, Matsuoka M. Development of a femtomolar-acting humanin derivative named colivelin by attaching activity-dependent neurotrophic factor to its N terminus: characterization of colivelin-mediated neuroprotection against Alzheimer’s disease-relevant insults in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10252–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3348-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Luciano F, Zhai D, Zhu X, Bailly-Maitre B, Ricci JE, Satterthwait AC, Reed JC. Cytoprotective peptide humanin binds and inhibits proapoptotic Bcl-2/Bax family protein BimEL. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15825–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hashimoto Y, Niikura T, Ito Y, Sudo H, Hata M, Arakawa E, Abe Y, Kita Y, Nishimoto I. Detailed characterization of neuroprotection by a rescue factor humanin against various Alzheimer’s disease-relevant insults. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9235–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09235.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhai D, Luciano F, Zhu X, Guo B, Satterthwait AC, Reed JC. Humanin binds and nullifies Bid activity by blocking its activation of Bax and Bak. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15815–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guo B, Zhai D, Cabezas E, Welsh K, Nouraini S, Satterthwait AC, Reed JC. Humanin peptide suppresses apoptosis by interfering with Bax activation. Nature. 2003;423:456–61. doi: 10.1038/nature01627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chiba T, Yamada M, Sasabe J, Terashita K, Shimoda M, Matsuoka M, Aiso S. Amyloid-beta causes memory impairment by disturbing the JAK2/STAT3 axis in hippocampal neurons. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:206–22. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chiba T, Yamada M, Aiso S. Targeting the JAK2/STAT3 axis in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:1155–67. doi: 10.1517/14728220903213426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yamada M, Chiba T, Sasabe J, Terashita K, Aiso S, Matsuoka M. Nasal Colivelin treatment ameliorates memory impairment related to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2020–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]