Abstract

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is caused by a deficiency in an adrenal enzyme resulting in alterations in Cortisol and aldosterone production. Bone status is affected by chronic glucocorticoid therapy and excess androgen exposure in children with CAH. This cross-sectional study enrolled participants with 21-hydroxylase deficiency from a pediatric referral center. Bone mineral density in the participants was normal when compared to age, gender and ethnicity adjusted standards, with respect to chronological age or bone age. Lean body mass was positively correlated with bone mineral content (BMC), independent of fat mass (p <0.001). There was no significant correlation between glucocorticoid dose or serum androgen levels and skeletal endpoints. In conclusion, lean body mass appears to be an important correlate of BMC in patients with CAH. The normal bone status may be explained by the differential effects of glucocorticoids on growing bone, beneficial androgen effects, or other disease specific factors.

Keywords: congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), bone mineral density, lean body mass, glucocorticoids, bone age

INTRODUCTION

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is a group of autosomal recessive disorders that cause a deficiency in an adrenal enzyme resulting in altered Cortisol and aldosterone secretion. Classic CAH, approximately 90% of cases, is caused by a deficiency of 21-hydroxylase, an enzyme that converts progesterone to deoxycorticosterone, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone to 11-deoxycortisol. The deficiency of 21-hydroxylase causes a decrease in negative feedback to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and subsequent hyperplasia of the adrenal gland. Cortisol and aldosterone precursors are subsequently diverted to androgens, causing increased virilization and a chronic hyperandrogenic state1. If untreated, those most severely affected will experience hyponatremic dehydration and hyperreninemia, progressing to hyperkalemia and subsequent shock. Therefore, infants diagnosed with 21-hydroxylase deficient CAH require immediate therapy with glucocorticoids to reduce excess accumulation of androgenic precursors1.

A careful hormonal balance must be maintained throughout childhood in order to maximize growth and limit a hyperandrogenic state. Full suppression of androgenic precursors is usually not possible without inducing iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome, and limiting growth and development2. Therefore, appropriately treated and compliant individuals with CAH are exposed to supraphysiological chronic glucocorticoid therapy throughout childhood and adolescence, as well as a hyperandrogenic milieu. This combination of factors puts these individuals at increased risk for the development of alterations in bone mineral density (BMD), bone mineral content (BMC) and body composition.

The interdependence of the muscle-bone unit has been understood since early necropsy studies correlated muscle weight with bone mass3. This relationship, termed the mechanostat theory in more recent literature4-6, has been evaluated by correlating lean body mass (LBM) with BMC using densitometry. The evaluation of growing bone during puberty has also suggested that the peak in LBM acquisition precedes and predicts the development of peak BMC7. This hypothesis of muscle development affecting bone strength can be assessed in the current clinical model in which potentially catabolic glucocorticoid supplementation is administered to children with CAH from the time of infancy. Glucocorticoids would be expected to promote fat mass accumulation and decrease the development of lean mass. However, androgen excess may have opposite and protective effects on body composition. Therefore, this study was designed to evaluate bone mass in children with CAH, and to examine the contributions of glucocorticoid therapy, androgen excess and body composition.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Participants included children and adolescents, ages 8-20 years old, with CAH diagnosed in the first year of life by elevated 17-hydroxyprogesterone level, newborn screen, adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) stimulation testing and/or genotyping. The patients were recruited from the Endocrinology Clinical Program of a tertiary pediatric referral center, Children’s Hospital Boston, between September 2004 and June 2005. All participants were healthy, had normal vital signs, and were receiving no additional medications known to affect androgen secretion or bone metabolism. The study was approved and all patients gave written informed consent or assent with parental consent, according to the guidelines of the Committee on Clinical Investigation at Children’s Hospital Boston.

Study design

The protocol included a cross-sectional evaluation of adrenal function, bone density, and body composition obtained after an overnight fast and prior to the morning glucocorticoid dose. All participants had a standard medical history and physical examination carried out by a pediatric endocrinologist (AF, CG), including a pubertal assessment with Tanner staging8. Heights were obtained in triplicate on a stadiometer (Perspective Enterprises, Kalamazoo, MI). Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) and body surface area (m2) were calculated using the measured weight and height on the day of the research visit. BMI percentile was calculated using age- and gender-specific tables provided by the Center for Disease Control (CDC), 2004.

At baseline, patients had an intravenous line placed for phlebotomy and urine was collected in the outpatient division of the General Clinical Research Center, Children’s Hospital Boston. Baseline samples were obtained between 08.00 and 11.00 h after an overnight fast. Patients collected a 24-hour urine sample during the week prior to the study visit. The baseline study included an assessment of adrenal status and pubertal development utilizing testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), DHEA-sulfate, luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), prolactin, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, androstenedione, and 24-hour urine for 17-ketosteroids.

Each participant underwent a bone density and body composition measurement by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan using a Hologic 4500 scanner with Delphi upgrade (Hologic Inc., Waltham, MA), including measurements of the total body, lumbar spine, total hip, and body composition. Hologic software was utilized for analysis and age-matched normative values based on American controls with pediatric reference standards9-11. Bone age radiographs were completed in all participants within 6 months of the study date. The bone age radiographs were interpreted using the standards of Greulich and Pyle by a pediatric radiologist and reviewed by a pediatric endocrinologist (AF). BMD z-scores were calculated based on chronological age and reevaluated according to bone age, if the bone age was advanced or delayed by more than one year. In order to account for skeletal growth during childhood in our sample, we calculated bone mineral apparent density (BMAD), utilizing the formulas: spine BMAD = BMC of lumbar spine/projected area of lumbar spine3/2, and hip BMAD = BMC of hip/projected area of femoral neck2, as previously described12. This calculation determines an areal density as g/cm2, in order to limit the impact of increased bone thickness on the measurement of bone density. Bone markers, including serum osteocalcin, alkaline phosphatase, serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and urinary N-telopeptides were obtained from the fasting blood and urine samples.

Assays

Assays for calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and alkaline phosphatase were performed in the Children’s Hospital Boston Chemistry Laboratory by Hitachi automated clinical analyzer (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). LH, FSH, estradiol, and prolactin were analyzed by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on an Elecsys analyzer (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). DHEA, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, and androstenedione were analyzed by HPLC then RIA in Children’s Hospital Boston Laboratory. DHEAS was analyzed by competitive binding chemiluminescent immunoassay on a Nichols Advantage analyzer (Nichols, San demente, CA). ACTH was measured by chemiluminescent immunoassay at ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, Utah. Urinary crossed linked N-telopeptides and osteocalcin (bone gla protein) were measured by chemiluminescent immunoassay at ARUP Laboratories. Although ARUP Laboratories does not report normative pediatric data for N-telopeptides, values were extrapolated from previously published normative data in children obtained from a morning urine sample13. Urinary 17-ketosteroids were assessed in a 24-hour urine sample by spectrophotometry at ARUP Laboratories. Total testosterone by HPLC tandem mass spectrometry, free testosterone by equilibrium dialysis, and SHBG by binding capacity were measured at Esoterix Inc, Austin, TX. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D was measured by competitive protein binding after column chromatography (Esoterix Inc.).

Data analysis

Using SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) statistical software, we tabulated standard parametric and non-parametric descriptive statistics. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation or standard error, as indicated. We tabulated the percentage of patients meeting the dichotomous criteria with binomial 95% CI. We assessed for skewedness and extreme values for continuous measures by graphical methods, as well as numerical indices. BMD is reported as an age- and sex-specific z-score and compared to the implicit norm of zero by one-sample t-test. Correlations were tested by Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients as appropriate to the distributions of the measures. Multiple regression was used to assess the contribution of possible confounders.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Seventeen patients, aged 8 to 20 years, were evaluated. The patients received daily glucocorticoids with a wide variation in dose noted (Table 1). Ten participants were treated with hydrocortisone, three with dexamethasone and four with prednisone. Seven of the participants had been suspected to be historically non-compliant by providers. Fourteen of the participants were known to have salt-wasting and were being treated with mineralocorticoid replacement therapy. The children were moderately overweight for height, with an average (50th percentile) mean height for age (Table 1). Ten participants were prepubertal, one in mid-puberty and six in late puberty. The morning baseline 17-hydroxyprogesterone concentrations reflected wide variability in the state of adrenal suppression, with the average value indicating lack of adequate adrenal suppression. The 24-hour urine collections for ketosteroids obtained during the week prior to the study visit were also variable, with five of the 13 samples higher than normal for age (38%), three patients with low 17-ketosteroids (23%) and five with normal values (38%). The mean values for the cohort were normal. Therefore, the data revealed a variable degree of adrenal suppression consistent with an unselected cohort of patients (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of the participants

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12.1 (4.1) | 8.1-20.3 |

| Gender (M/F) | 6/11 | |

| Pubertal Tanner stage (1/2/3/4/5) | 10/1/0/3/3 | |

| Height percentile | 50.2 (33.4) | 1-95 |

| Weight percentile | 62.6 (28.6) | 0-99 |

| BMI percentile | 64.8 (26.8) | 2-98 |

| Waist/hip ratio | 0.87 (0.07) | 0.79-1.04 |

| Glucocorticoid dose (mg/kg/day) | 0.44 (0.16) | 0.24-0.83 |

| Glucocorticoid dose (mg/m2) | 14.30(5.74) | 7.09-29.36 |

TABLE 2.

Adrenal metabolites of the participants

| Mean (SD) | Median (range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Testosterone | ||

| nmol/I | 0.98(1.6) | 0.35 (0-5.8) |

| ng/dl | 28.2 (45.4) | 10.2 (0-167) |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) | ||

| nmol/1 | 2.2 (3.7) | 0.85 (0.35-13.7) |

| ng/dl | 64.5 (105.7) | 24.5 (10.1-395) |

| DHEA sulfate | ||

| mmol/l | 0.56(0.88) | 0. 28 (0.05-3.51) |

| μB/dl | 20.6 (32.2) | 10.2 (2.0-129.1) |

| 17-Hyd roxy progesterone | ||

| nmol/1 | 67.6(91.4) | 38.9(0.3-345.6) |

| ng/dl | 2232.4 (3,017.7) | 1,285 (10-11,407) |

| Androstenedione | ||

| nmol/1 | 3.9(5.1) | 2.1 (0.42-19.58) |

| ng/dl | 111.6(146.4) | 59(12-561) |

| 24 hour urinary 17 ketosteroids | ||

| μmol/day | 16.0(8.9) | 15.3 (3.8-38.1) |

| mg/day | 4.6 (2.6) | 4.4(1.1-11) |

Normative values vary by gender and pubertal stage. See text for interpretation of results.

Skeletal evaluations

BMD z-scores, corrected for age, gender and ethnicity, were < −2.0 standard deviations (SD) in only one of the 17 participants. This individual also had significantly delayed bone age and pubertal stage. When corrected for bone age, this participant’s BMD z-scores were all >0. Fourteen of 17 (82%) participants had a normal BMD (defined as BMD z-score > −1.0 SD) at all sites. Seven participants (41%) had bone age assessments that were more than 1 year discrepant from their chronological age. Six of the seven children (86%) had advanced bone ages. None of these participants had pubertal advancement as measured by breast or testicular changes. However, five had premature development of pubic and axillary hair. Thus, the bone age advancement was determined to be an appropriate adjustment for excess androgen exposure. A re-analysis of the DXA results adjusted for bone age also revealed normal mean BMD z-scores for corrected bone age, gender and ethnicity. Fourteen of 17 (82%) participants had normal BMD z-scores after correction for bone age. Two of the three participants with chronological z-scores < −1.0 SD were the same individuals who had bone age-corrected z-scores of < −1.0 SD (Table 3). These two participants were late-pubertal females. The additional participant with a bone age-corrected z-score of < −1.0 SD was a prepubertal male.

TABLE 3.

Bone mineral density z-scores for chronological age and adjusted for bone age

| Chronological age |

Bone age |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | |

| Total body | 0.93(1.3) | −1.3 to 3.4 | 0.75 (1.2) | −0.9 to 3.0 |

| Hip | 0.51(1.1) | −1.4 to 2.2 | 0.32(0.94) | −1.4 to 1.6 |

| Spine | 0.16(1.3) | −2.6to2.4 | 0.01 (0.77) | −1.5 to 1.4 |

Bone turnover was evaluated using urinary and serum markers (Table 4). Osteocalcin was low for age in 11/14 (73%) participants. All serum alkaline phosphatase, calcium and phosphorus concentrations were within the normal range. The mean N-telopeptide level was 272 nMBEC (nmol of bone collagen equivalent/mM of creatinine). Seven of 15 (54%) samples were elevated for age and pubertal status, consistent with increased bone resorption. Three patients (20%) had decreased concentrations and five (33%) were in the normal range compared to previously reported pediatric normative data13. The concentrations did not correlate with age, glucocorticoid dose or measurements of adrenal androgen production. One of ten participants (10%) evaluated had a 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration of less than assay (<12.5 nmol/1 or <5 ng/ml), consistent with vitamin D deficiency (Table 4). This participant was an 8 year-old Caucasian prepubertal female who had normal bone parameters. The duration and contribution of this deficiency cannot be evaluated in the cross-sectional analysis. However, clinical treatment and follow up are warranted.

TABLE 4.

Biochemical parameters of bone metabolism

| Mean (SD) | Median (range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium | ||

| mmol/1 | 2.4 (0.09) | 2.4 (2.3-2.6) |

| mg/dl | 9.5 (0.3) | 9.5(9-10.3) |

| Phosphate | ||

| mmol/l | 1.4 (0.13) | 1.4(1.2-1.7) |

| mg/dl | 4.3 (0.41) | 4.3 (3.7-5.2) |

| N-Telopeptide nMBCE/mM | 286.8(172.7) | 294 (46-597) |

| Osteocalcin | ||

| nmol/1 | 2.2 (2.0) | 1.9 (0.2-7.1) |

| ng/ml | 13.1 (11.5) | 11.4 (0.9-41.2) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | ||

| ukat/l | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.4 (0.9-4.6) |

| U/l | 184.4 (76.6) | 205 (55-275) |

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D | ||

| nmol/l | 57.7(24.0) | 64.9 (<12.5-77.4) |

| ng/ml | 23.1 (9.6) | 26 (<5.0-31) |

Normative values vary by gender and pubertal stage. See text for interpretation of results. BCE = bone collagen equivalent.

Bivariate correlations

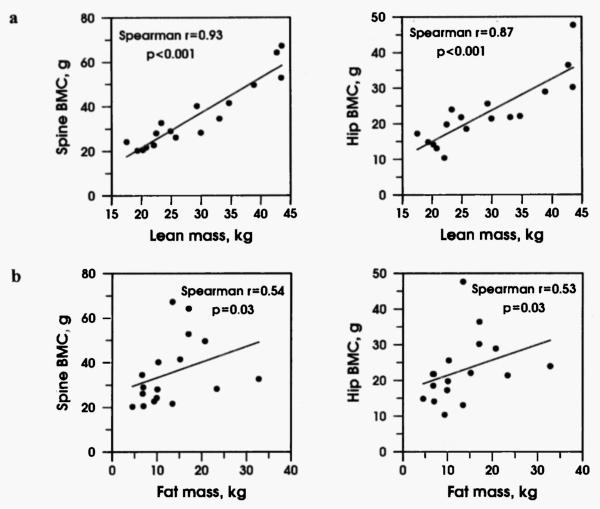

Neither BMD nor BMC were correlated with glucocorticoid dose (Spearman r = −0.1, p = 0.7) or baseline androgen levels (r = −0.06, p = 0.9). In addition, neither pubertal stage nor gender correlated with BMD z-scores. As anticipated, pubertal progression correlated with increasing BMC (r = 0.7, p = 0.002). To correct for volumetric changes in BMD that can occur with growth in children, we performed the additional calculation of BMAD12. Spine and hip BMAD did not correlate negatively with glucocorticoid dose, or positively with measurements of androgen precursors. The only significant correlation was a negative correlation of 17-hydroxyprogesterone with the BMAD of the hip (p <0.03). LBM was significantly correlated with BMC (r = 0.93, p = <0.001). Fat mass was also correlated with BMC, (r = 0.54, p = 0.03) but to a lesser degree than LBM (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

a. Spine and hip bone mineral content (BMC) are strongly correlated with lean mass (p <0.001). b. Spine and hip BMC are moderately correlated with fat mass (p = 0.03).

Regression analysis

LBM was a significant predictor of BMC (linear regression p <0.001). Age and height were possible confounders, although the addition of height, but not age to the model rendered the LBM contribution non-significant (p >0.1). The total body fat mass correlated with BMC (p <0.03). However, the correlation of fat mass with BMC was not significant when tested in a multivariable model and did not reduce the significance of LBM (p <0.001). Therefore, LBM appeared to be the more important factor, because it predicted BMC independent of fat mass.

DISCUSSION

This study of treated children with classic CAH provides an opportunity to evaluate the effects of chronic glucocorticoid therapy on BMC and bone density in the setting of hyperandrogenism. BMD has been shown to be diminished by the use of glucocorticoids in individuals of all ages, genders and underlying conditions through mechanisms that involve both osteoclast and osteoblast alterations14. Studies of adults with classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency CAH suggest that BMD is reduced in these patients15,16. However, studies have provided conflicting data, with some investigators showing normal bone density in the participants17. Studies in children have yielded similarly conflicting results. The majority of studies have found normal bone density in both children and young adults with CAH18-22. However, some data indicate skeletal deficits23. Bone mineral density and bone mineral content in our participants were normal and did not correlate with current glucocorticoid dose or androgen levels. The data obtained utilizing a volumetric correction (BMAD) suggest that those individuals with elevated 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels had lower hip BMAD scores. The elevated 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels may have identified those individuals who were more resistant to therapy and, thus, were more likely to have required higher lifetime glucocorticoid exposures. However, the elevated levels may also represent non-compliant or intermittently compliant individuals and thus represent participants with less glucocorticoid exposure, which would be more difficult to explain physiologically. Therefore, these and other data suggest that multiple factors, such as body mass index, gender, duration and dosage of therapy, contribute to bone status in children and young adults with CAH24.

In a recent analysis of BMD in children with intermittent glucocorticoid use for nephrotic syndrome, Leonard et al.25 found that children treated intermittently with high doses of glucocorticoids had a BMD consistent with an age-matched control population. That study suggested that alterations in body composition, specifically increased BMI, may have served as a protective factor in this population. In addition, the transient nature of the glucocorticoid exposure may have allowed for bone recovery in the intervening periods. Other studies of glucocorticoid exposure in children have been carried out in the setting of chronic inflammatory conditions or oncological disease which may cause alterations in bone formation secondary to the underlying disease26-30. Therefore, the current study provides a model of lifelong supraphysiological daily glucocorticoid exposure without an underlying inflammatory process, increased BMI, or altered body composition often associated with the pharmacological doses of glucocorticoid therapy required in inflammatory disease states.

Although the majority of previous studies in CAH have demonstrated normal BMD and BMC, consistent with our findings, the literature suggests that children and adults with this diagnosis have depressed bone turnover, reflected by altered patterns of bone turnover markers31,32. Our bone turnover data support the theory that there is an uncoupling of bone turnover in patients with CAH, with low osteocalcin values and elevated N-telopeptide levels seen in the majority of participants. These alterations in bone turnover could eventually result in deleterious effects on bone mass. Due to the young age of our patients, whether these alterations in bone turnover ultimately mediate skeletal deficits can only be definitively answered by a longitudinal study in this population.

Recent data in healthy young adults and in overweight children and adolescents have suggested that lean tissue mass may be more important than fat mass as a contributor to bone density33,34. Therefore, more emphasis has been placed on the contribution of lean mass to BMC in both lean and obese children and adolescents. LBM has been shown to be normal in children and young adults with classic CAH18. We propose that the normal BMD seen in the current sample may be related to the preservation of LBM in the setting of chronic glucocorticoid use. This hypothesis would help explain the preservation of bone mass despite this medication’s potential catabolic effects, and would explain the normal BMD and BMC in both lean and obese patients with CAH.

Limitations of the current study must be considered. The study was limited by the sample size due to the frequency of the disease in question, one in 16,000, and the limitations of pediatric research from a single institution. In addition, the participants were given the option of refusing portions of the protocol, and therefore all data were not obtained in each participant. The heterogeneity of the adrenal status of the participants reflects the cross-sectional design, with measurements obtained at a single time point, and therefore may limit the ability to determine the lifelong affects of excess androgens on bone status. However, the variability in compliance and adrenal status makes the results more generalizable to an unselected population.

In conclusion, in our sample of children and adolescents exposed to the potential catabolic effects of lifelong glucocorticoid therapy, the normal bone density seen may reflect the contribution of LBM, perhaps conferred by intermittent androgen excess. The data contribute to a growing body of literature that emphasizes the importance of the muscle-bone unit. This is, to our knowledge, the first study to describe this relationship in children with 21-hydroxylase deficiency. LBM should be an important consideration in the assessment of risk for low bone mass in all children and adolescents with chronic disease, including those receiving medications that may affect both body composition and bone density.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was supported by an investigator initiated grant from Pfizer, Inc., and the Clinical Investigator Training Program: Harvard-MIT Health Sciences and Technology-Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, in collaboration with Pfizer Inc. and Merck & Company, Inc., and NIH grant M01-RR-2172 from the National Institutes of Health to the Children’s Hospital Boston General Clinical Research Center.

We gratefully acknowledge the nursing care provided by the Children’s Hospital Boston General Clinical Research Center; Jessica Sexton and Diane DiFabio for technical assistance with the DXA measurements; Dr. Joseph Majzoub for his guidance in study design and manuscript preparation; and our participants who made this research possible.

REFERENCES

- 1.Speiser PW, White PC. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:776–788. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Migeon CJ, Wisniewski AB. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia owing to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Growth, development, and therapeutic considerations. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2001;30:193–206. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(08)70026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doyle F, Brown J, Lachance C. Relation between bone mass and muscle weight. Lancet. 1970;i:391–393. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)91520-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frost HM. Muscle, bone, and the Utah paradigm: a 1999 overview. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:911–917. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rauch F, Schoenau E. The developing bone: slave or master of its cells and molecules? Pediatr Res. 2001;50:309–314. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200109000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burr DB. Muscle strength, bone mass, and age-related bone loss. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1547–1551. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.10.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rauch F, Bailey DA, Baxter-Jones A, Mirwald R, Faulkner R. The ‘muscle-bone unit’ during the pubertal growth spurt. Bone. 2004;34:771–775. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Growth and physiological development during adolescence. Annu Rev Med. 1968;19:283–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.19.020168.001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonard MB, Shults J, Elliott DM, Stallings VA, Zemel BS. Interpretation of whole body dual energy X-ray absorptiometry measures in children: comparison with peripheral quantitative computed tomography. Bone. 2004;34:1044–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zemel BS. Reference data for the whole body, lumbar spine and proximal femur for American children relative to age, gender and body size. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;1:S231. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly T. Bone mineral density reference database for American men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 1990:S249. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katzman DK, Bachrach LK, Carter DR, Marcus R. Clinical and anthropometric correlates of bone mineral acquisition in healthy adolescent girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73:1332–1339. doi: 10.1210/jcem-73-6-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mora S, Prinster C, Proverbio MC, Bellini A, de Poli SC, Weber G, Abbiati G, Chiumello G. Urinary markers of bone turnover in healthy children and adolescents: age-related changes and effect of puberty. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998;63:369–374. doi: 10.1007/s002239900542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rehman Q, Lane NE. Effect of glucocorticoids on bone density. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;41:212–216. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaaskelainen J, Voutilainen R. Bone mineral density in relation to glucocorticoid substitution therapy in adult patients with 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1996;45:707–713. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1996.8620871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagenfeldt K, Martin Ritzen E, Ringertz H, Helleday J, Carlstrom K. Bone mass and body composition of adult women with congenital virilizing 21-hydroxylase deficiency after glucocorticoid treatment since infancy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;143:667–671. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1430667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo CY, Weetman AP, Eastell R. Bone turnover and bone mineral density in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1996;45:535–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1996.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stikkelbroeck NM, Oyen WJ, van der Wilt GJ, Hermus AR, Otten BJ. Normal bone mineral density and lean body mass, but increased fat mass, in young adult patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1036–1042. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girgis R, Winter JS. The effects of glucocorticoid replacement therapy on growth, bone mineral density, and bone turnover markers in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3926–3929. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mora S, Saggion F, Russo G, Weber G, Bellini A, Prinster C, Chiumello G. Bone density in young patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Bone. 1996;18:337–340. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(96)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cameron FJ, Kaymakci B, Byrt EA, Ebeling PR, Warne GL, Wark JD. Bone mineral density and body composition in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:2238–2243. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.7.7608286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gussinye M, Carrascosa A, Potau N, Enrubia M, Vicens-Calvet E, Ibanez L, Yeste D. Bone mineral density in prepubertal and in adolescent and young adult patients with the salt-wasting form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Pediatrics. 1997;100:671–674. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paganini C, Radetti G, Livieri C, Braga V, Migliavacca D, Adami S. Height, bone mineral density and bone markers in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Horm Res. 2000;54:164–168. doi: 10.1159/000053253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Almeida Freire PO, de Lemos-Marini SH, Maciel-Guerra AT, Morcillo AM, Matias Baptista MT, de Mello MP, Guerra G., Jr Classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency: a cross-sectional study of factors involved in bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Metab. 2003;21:396–401. doi: 10.1007/s00774-003-0434-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonard MB, Feldman HI, Shults J, Zemel BS, Foster BJ, Stallings VA. Long-term, high-dose glucocorticoids and bone mineral content in childhood glucocorticoid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:868–875. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bechtold S, Ripperger P, Dalla Pozza R, Schmidt H, Hafner R, Schwarz HP. Musculoskeletal and functional muscle-bone analysis in children with rheumatic disease using peripheral quantitative computed tomography. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:757–763. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1747-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falcini F, Bindi G, Simonini G, Stagi S, Galluzzi F, Masi L, Cimaz R. Bone status evaluation with calcaneal ultrasound in children with chronic rheumatic diseases. A one year follow-up study. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cetin A, Celiker R, Dincer F, Ariyurek M. Bone mineral density in children with juvenile chronic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 1998;17:551–553. doi: 10.1007/BF01451301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulder JE, Bilezikian JP. Bone density in survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Densitom. 2004;7:432–442. doi: 10.1385/jcd:7:4:432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atkinson SA, Halton JM, Bradley C, Wu B, Barr RD. Bone and mineral abnormalities in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: influence of disease, drugs and nutrition. Int J Cancer Suppl. 1998;11:35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lisa L, Neradilova M, Tomasova N, Soutorova M, Zimak J. Osteocalcin in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Bone. 1995;16:57–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hargitai G, Hosszu E, Halasz Z, Solyom J. Serum osteocalcin and insulin-like growth factor I levels in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Horm Res. 1999;52:131–139. doi: 10.1159/000023449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang MC, Bachrach LK, Van Loan M, Hudes M, Flegal KM, Crawford PB. The relative contributions of lean tissue mass and fat mass to bone density in young women. Bone. 2005;37:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petit MA, Beck TJ, Shults J, Zemel BS, Foster BJ, Leonard MB. Proximal femur bone geometry is appropriately adapted to lean mass in overweight children and adolescents. Bone. 2005;36:568–576. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]