Abstract

Stereospecific coupling of benzylic carbamates and pivalates with aryl- and heteroarylboronic esters has been developed. The reaction proceeds with selective inversion or retention at the electrophilic carbon depending on the nature of the ligand. Tricyclohexylphosphine ligand provides product with retention, while an NHC ligand provides product with inversion.

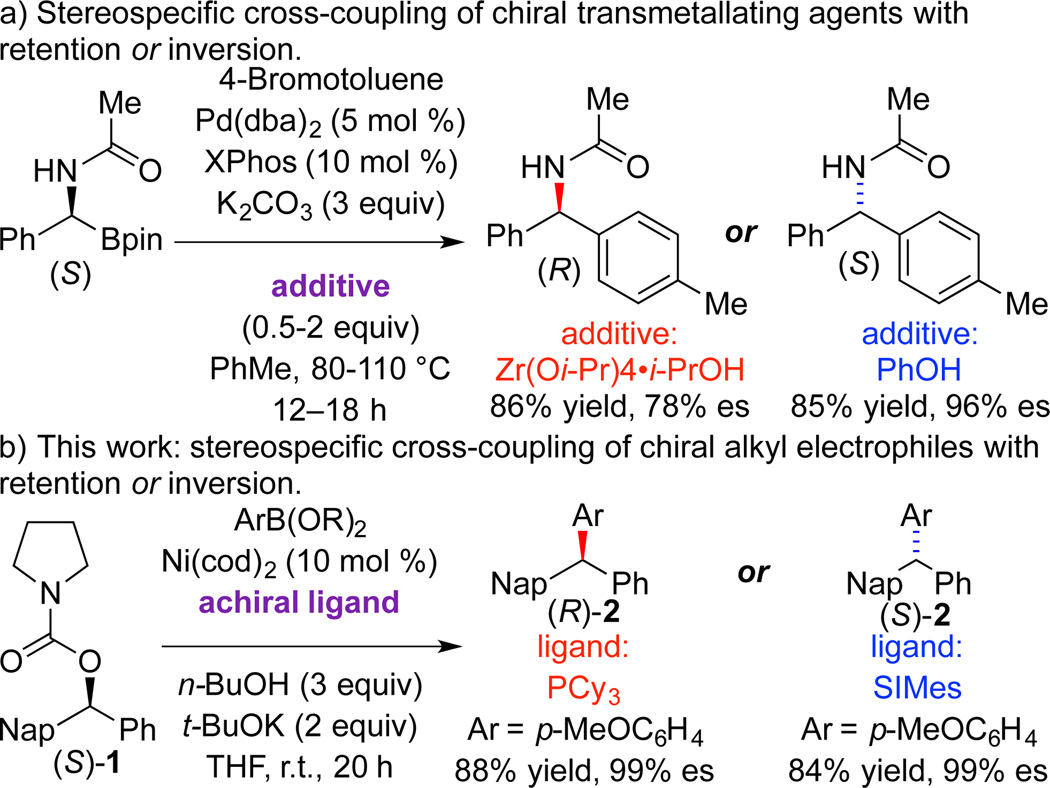

The mechanisms of alkyl cross-coupling reactions are hardwired with implications for the stereochemical outcome at the reactive centers.1 Simple changes to the reaction conditions do not typically perturb the inherent bias for racemization, retention, or inversion at the reactive centers. For example, palladium-catalyzed reactions of alkyl electrophiles are typically stereospecific and proceed with inversion at the stereogenic center,2,3 while nickel-catalyzed reactions of alkyl halides proceed with racemization at the electrophilic carbon4 and judicious use of chiral catalyst permits stereoconvergent reactions.5 Overcoming the intrinsic preference, such that a reaction that typically proceeds with inversion at the stereogenic center can proceed with retention is quite unusual, and requires a significant change to the mechanism of the transformation. For stereospecific reactions, special cases using α-chiral transmetallating agents have been reported where modification of reaction conditions or substrate structure can affect a switch in the sense of absolute stereo-chemistry.6 Transmetallation typically occurs with retention at the stereogenic center;7,8 select examples that proceed with inversion have been reported.9 In seminal contributions, Hiyama demonstrated that palladium-catalyzed couplings of alkylsilanes could proceed with retention or inversion, depending on the reaction conditions.10 Recently, the Suginome group has developed stereodivergent reactions of α-(acetylamino)benzylboronic esters that are controlled by choice of additive to afford, selectively, either retention or inversion (Scheme 1a).11,12

Scheme 1.

Control of product stereochemistry in stereospecific reactions

In this communication, we demonstrate catalyst control of the stereochemical course with respect to the electrophilic partner in a cross-coupling reaction. Stereospecific nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of benzylic alcohol derivatives typically proceed with inversion at the electrophilic carbon.13,14 In this manuscript we report nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of benzylic esters where the achiral ligand structure dictates whether the reaction proceeds with retention or inversion (Scheme 1b). Use of SIMes, an N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligand, affords inversion, while PCy3 gives retention. To the best of our knowledge, these results constitute the first cross-coupling reactions of alkyl electrophiles that undergo two distinct stereospecific mechanistic pathways to provide either retention or inversion at the electrophilic carbon.

In previous work, we established synthesis of enantioenriched triarylmethanes by stereospecific nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of ethers with aryl Grignard reagents.13b The triarylmethane moiety is present in medicinal chemistry targets, natural products, and synthetic materials.15,16 Despite recent advances in the preparation of racemic triarylmethanes,17 there are few methods for their enantioselective synthesis.18 As part of our ongoing interest in developing nickel-catalyzed stereospecific reactions of alkyl electrophiles, we chose to examine cross-coupling reactions of arylboronic esters for triarylmethane synthesis. The functional group tolerance and ready availability of a wide range of boronic esters makes them attractive coupling partners.

We began by examining a range of benzylic alcohol derivatives (Table 1). Our initial reaction conditions resulted in a modest conversion of carbonate (S)-3 and low enantiospecificity (es; entry 1).19 To our surprise, in contrast to the Kumada coupling, the product, (R)-2, results from retention at the electrophilic carbon. An improvement to 43% es was observed when the solvent was changed from toluene to THF (entry 2). Alcohol additives further improved the yield and stereo-chemical fidelity of the reaction, with n-BuOH providing the highest es, 87% (entry 4). More sterically encumbered alcohols provided more modest improvements, while water and the electron-deficient alcohol trifluoroethanol proved detrimental to the reaction (entries 3, 5, and 7). The enantiospecificity of the reaction showed a marked dependence on the identity of the leaving group. While the use of pivalate (S)-4 in the cross-coupling reaction resulted in lower enantiomeric excess of the product (entry 8), the benzoate and carbamate derivatives (S)-5 and (S)-1 showed a significant increase in product ee, providing 91 and 95% es, respectively (Table 1, entries 8, 10, and 12). An additional small improvement in yield and es resulted from using a 1:1 mixture of THF:toluene as the solvent (c.f. entries 12 and 15).

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditions.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | liganda | solvent | additive | %yieldb | esc | retention/ inverson |

| 1 |  |

PCy3 | PhMe | none | 46 | 7 | retention |

| 2 | PCy3 | THF | none | 53 | 43 | retention | |

| 3 | PCy3 | THF | H2O | 74 | 10 | retention | |

| 4 | PCy3 | THF | n-BuOH | 76 | 87 | retention | |

| 5 | PCy3 | THF | i-ProH | 46 | 78 | retention | |

| 6 | PCy3 | THF | t-BuOH | 55 | 43 | retention | |

| 7 | PCy3 | THF | F3CCH2OH | <5 | na | retention | |

| 8 |  |

PCy3 | THF | n-BuOH | 53 | 76 | retention |

| 9 | SIMes | THF | n-BuOH | 60 | 77 | inversion | |

| 10 |  |

PCy3 | THF | n-BuOH | 57 | 91 | retention |

| 11 | SIMes | THF | n-BuOH | 83 | >99 | inversion | |

| 12 |  |

PCy3 | THF | n-BuOH | 62 | 95 | retention |

| 13 | PCy3 | THF/PhMe | none | 67 | 35 | retention | |

| 14 | SIMes | THF/PhMe | none | 82 | 92 | inversion | |

| 15 | PCy3 | THF/PhMe | n-BuOH | 88 | 99 | retention | |

| 16 | SIMes | THF/PhMe | n-BuOH | 84 | 99 | inversion | |

PCy3 (20 mol %), SIMes (11 mol %).

Isolated yield after column chromatography.

Enantiospecificity (es) = eeproduct/eestarting material × 100%.

We examined other ligands20 under the reaction conditions and found that the NHC ligand SIMes21 afforded comparable yields and enantiospecificity of 2, however, the major product was the (S)-enantiomer, resulting from inversion at the electrophilic carbon.22 Catalyst-control of the stereochemical outcome of the reaction was consistent across the range of esters and carbamates that we examined: PCy3 and SIMes reliably afforded opposite enantiomers of product (entries 8–11, 15 and 16).23 Under the optimal reaction conditions conditions, addition of n-BuOH was found to improve stereochemical fidelity when using either ligand (c.f. entries 13–16).

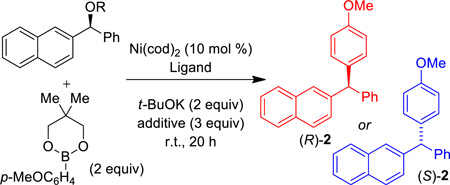

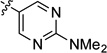

Having optimized reaction conditions for stereospecfic synthesis of either enantiomer of product, we turned our attention to the scope of the reaction with respect to the boronic ester (Table 2). Electron donating and withdrawing substituents on the arylboronic ester are well tolerated under the reaction conditions (entries 1–8), which are mild and allow for broad functional group tolerance. Boronic esters containing ketone, free alcohol and carbamate functional groups all couple in good yield and es (entries 9–14). Heterocyclic boronic esters including pyrimidine, furan, and indole underwent smooth cross-coupling (entries 15–20). The reaction conditions developed for the formation of either enantiomer of 2 are general across the range of boronic esters that we examined: of 20 examples, 18 provide high es. Therefore, by choosing the appropriate ligand, PCy3 or SIMes, either enantiomer of a given product can be obtained from the same enantiomer of starting material.

Table 2.

Scope with respect to arylboronic ester.a

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ar | ligandb | yield (%)c | SM ee (%)d | product ee (%)d | es (%) | retention/ inversion |

|

| 1 | R' = OMe | PCy3 | 88 | 93 | 92 | 98 | retention | |

| 2 | OMe | SIMes | 84 | 93 | 93 | >99 | inversion | |

| 3 | NMe2 | PCy3 | 86 | 93 | 92 | 99 | retention | |

| 4 | NMe2 | SIMes | 71 | 93 | 92 | 98 | inversion | |

| 5 | F | PCy3 | 82 | 93 | 90 | 97 | retention | |

| 6 | F | SIMes | 80 | 97 | 88 | 91 | inversion | |

| 7 | CF3 | PCy3 | 88 | 97 | 57 | 59 | retention | |

| 8 | CF3 | SIMes | 70 | 93 | 91 | 98 | inversion | |

| 9 | COMe | PCy3 | 76 | 93 | 89 | 96 | retention | |

| 10 | COMe | SIMes | 98 | 98 | 97 | 99 | inversion | |

| 11 | CH2OH | PCy3 | 67 | 93 | 82 | 88 | retention | |

| 12 | CH2OH | SIMes | 0 | 97 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 13 | CH2NHBoc | PCy3 | 84 | 93 | 91 | 98 | retention | |

| 14 | CH2NHBoc | SIMes | 94 | 98 | 97 | 97 | inversion | |

| 15 |  |

PCy3 | 86 | 93 | 89 | 96 | retention | |

| 16e | SIMes | 75 | 98 | 92 | 94 | inversion | ||

| 17 |  |

PCy3 | 79 | 93 | 94 | >99 | retention | |

| 18 | SIMes | 65 | 98 | 83 | 85 | inversion | ||

| 19 |  |

PCy3 | 90 | 93 | 93 | 99 | retention | |

| 20 | SIMes | 71 | 93 | 92 | 98 | inversion | ||

All data are average of two experiments unless other-wise indicated.

PCy3 (20 mol %), SIMes (11 mol %).

Isolated yield after column chromatography.

Determined by chiral SFC chromatography.

Data obtained from a single experiment.

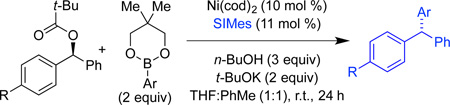

We set as our goal the cross-coupling of oxidative additon partners that do not include a naphthylene moiety. These electrophiles are typically less reactive in cross-coupling reactions,13c and were not competent for triarylmethane synthesis via Kumada coupling.13b Indeed, neither the corresponding carbamates nor the use of PCy3 as ligand provide acceptable yields of product. However, benzhydril pivalates undergo smooth cross-coupling under our optimized reaction conditions when SIMes is utilized as the ligand (Table 3). Efficient cross-coupling is achieved for pivalates with a range of arylboronic esters (entries 1–4). Functionality is also tolerated on the electrophile: furan and benzodioxane substituted pivalates couple in good yield and excellent es (entries 5 and 6).

Table 3.

Scope of oxidative addition partner.a

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | Ar | yield (%)b | SM ee (%)c | product ee (%)c | es (%) |

| 1 | Ph | p-MeOC6H4 | 85 | 96 | 84 | 88 |

| 2 | Ph | p-(Me2N)C6H4 | 75 | 82 | 79 | 96 |

| 3 | Ph | p-(BocNHCH2)C6H4 | 54 | 98 | 92 | 94 |

| 4 | Ph |  |

66 | 96 | 96 | >99 |

| 5 | 80 | 93 | 87 | 94 | ||

| 6 |  |

60 | 93 | 93 | 99 | |

All data are average of two experiments.

Isolatedyield after column chromatography.

Determined by chiral SFC chromatography.

In summary, we have developed a nickel-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction for the synthesis of enantioenriched triarylmethanes. Reactions proceed with high stereochemical fidelity. Achiral ligand identity controls whether the reaction proceeds with inversion or retention at the electrophilic carbon, therefore either enantiomer of product can be formed from a single enantiomer of starting material. This method expands the range of triarylmethanes that may be prepared in enantioenriched form, as simple benhydril pivalates and a variety of functionalized arylboronic esters, including heterocyclic compounds can be used in the reaction. Efforts to further expand the scope of the reaction and elucidate the mechanistic details are underway.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by NIH NIGMS (R01GM100212), the University of California Cancer Research Coordinating Committee, University of California for a Chancellor’s Fellowship (M. R. H.), the Ford Family Foundation Predoctoral Fellowship (M. R. H.), DOE GAANN PA200A120070 (L. E. H.). We thank Frontier Scientific for generous donations of boronic acids. Dr. Joseph Ziller and Dr. John Greaves are acknowledged for X-ray crystallographic and mass spectrometry data, respectively.

Funding Sources

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures and characterization data, including X-ray crystallographic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

No competing financial interests have been declared.

Contributing author solved X-ray structure of compound (S)-Table 2, entry 19.

References

- 1.Jana R, Pathak TP, Sigman MS. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1417. doi: 10.1021/cr100327p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Lau KSY, Fries RW, Stille JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:4983. [Google Scholar]; (b) Netherton MR, Fu GC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:3910. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021018)41:20<3910::AID-ANIE3910>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Legros J-Y, Toffano M, Fiaud J-C. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:3235. [Google Scholar]; (d) Rodriquez N, de Arellano CR, Asensio G, Medio-Simon M. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:4223. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lopez-Perez A, Adrio J, Carretero JC. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5514. doi: 10.1021/ol902335c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) He A, Falck JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2524. doi: 10.1021/ja910582n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Rudolph A, Rackelmann N, Lautens M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:1485. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pd-catalyzed allylic substitutions can occur with inversion or retention, depending on the nucleophile. See: Trost BM, VanVranken DL. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:395. doi: 10.1021/cr9409804.

- 4.Stille JK, Cowell AB. J. Organomet. Chem. 1977;124:253. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Saito B, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6694. doi: 10.1021/ja8013677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wilsily A, Tramutola F, Owston NA, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:5794. doi: 10.1021/ja301612y. and cited therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Glorius F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:8347. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For a discussion, see: Molander GA, Wisniewski SR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:16856. doi: 10.1021/ja307861n.

- 7.For labeling studies, see: Bock PL, Boschetto DJ, Rasmussen JR, Demers JP, Whitesides GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:2814. Ridgway BH, Woerpel KA. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:458. doi: 10.1021/jo970803d. Matos K, Soderquist JA. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:461. doi: 10.1021/jo971681s. Taylor BLH, Jarvo ER. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:7573. doi: 10.1021/jo201263r.

- 8.(a) Ye J, Bhatt RK, Falck JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hölzer B, Hoffmann RW. Chem. Commun. 2003:732. doi: 10.1039/b300033h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Campos KR, Klapars A, Waldman JH, Dormer PG, Chen C-Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:3538. doi: 10.1021/ja0605265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lange H, Fröhlich R, Hoppe D. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:9123. [Google Scholar]; (e) Imao D, Glasspoole BW, Laberge SV, Crudden CM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5024. doi: 10.1021/ja8094075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Li H, He A, Falck JR, Liebeskind LS. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3682. doi: 10.1021/ol201330j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) See reference 5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) LaBadie JW, Stille JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:669. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kells KW, Chong JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15666. doi: 10.1021/ja044354s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sandrock DL, Jean-Gérard L, Chen C-Y, Dreher SD, Molander GA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17108. doi: 10.1021/ja108949w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ohmura T, Awano T, Suginome M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:13191. doi: 10.1021/ja106632j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lee JCH, McDonald R, Hall DG. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:894. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Hatanaka Y, Hiyama T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:7793. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hiyama T. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002;653:58. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Awano T, Ohmura T, Suginome M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:20738. doi: 10.1021/ja210025q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) reference 9d. [Google Scholar]

- 12.For enantiodivergent reactions of alkyllithium reagents: Stymiest JL, Bagutski V, French RM, Aggarwal VM. Nature. 2008;456:778. doi: 10.1038/nature07592.

- 13. Taylor BLH, Swift EC, Waetzig JD, Jarvo ER. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:389. doi: 10.1021/ja108547u. Taylor BLH, Harris MR, Jarvo ER. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:7790. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202527. Greene MA, Yonova IM, Williams FJ, Jarvo ER. Org. Lett. 2012;14:4293. doi: 10.1021/ol300891k. For a review, see: Taylor BLH, Jarvo ER. Synlett. 2011;19:2761.

- 14.For recent studies of the stereochemical course of nickel-catalyzed reactions of epoxides and aziridines, see: Beaver MG, Jamison TF. Org. Lett. 2011;13:4140. doi: 10.1021/ol201702a. Sylvester KT, Wu K, Doyle AG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:9541. doi: 10.1021/ja3079362. Lin BL, Clough CR, Hillhouse GL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:2890. doi: 10.1021/ja017652n.

- 15.Biological activity: Palchaudhuri R, Nesterenko V, Hergenrother PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10274. doi: 10.1021/ja8020999. Shagufta: Srivastava AK, Sharma R, Mishra R, Balapure AK, Murthy PSR, Panda G. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:1497. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.10.002. Parai MK, Panda G, Chaturvedi V, Manju YK, Sinha S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:289. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.083. Ellsworth BA, Ewing WR, Jurica E. 2011/0082165A1. U.S. Patent Application. 2011 Apr 7; Baba K, Maeda K, Tabata Y, Doi M, Kozawa M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988;36:2977. Materials: Herron N, Johansson GA, Radu NS. 2005/0187364. US Patent Application. 2005 Aug 25; Xu Y-Q, Lu J-M, Li N-J, Yan F, Xia X, Xu Q. Eur. Polym. J. 2008;44:2404.

- 16.Physical properties of triarylmethanes: Breslow R, Chu W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:411. doi: 10.1021/ja00791a031. Finocchiaro P, Gust D, Mislow K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:3198. Duxbury DF. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:381.

- 17. Zhang J, Bellomo A, Creamer AD, Dreher SD, Walsh PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:13765. doi: 10.1021/ja3047816. Yu J-Y, Kuwano R. Org. Lett. 2008;10:973. doi: 10.1021/ol800078j. Molander GA, Elia MD. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:9198. doi: 10.1021/jo061699f. Li Y-Z, Li B-J, Lu X-Y, Lin S, Shi Z-J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:3817. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900341. Iovel I, Mertins K, Kischel J, Zapf A, Beller M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:3913. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462522. Representative Freidel-Crafts strategy, see: Esquivias J, Arrayás RG, Carretero JC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:629. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503305.

- 18.(a) Shi B-F, Maugel N, Zhang Y-H, Yu J-Q. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:4882. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun F-L, Zheng X-J, Gu Q, He Q-L, You S-L. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010:47. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Es: Denmark SE, Vogler T. Chem.–Eur. J. 2009;15:11737. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.For results with other ligands, see the SI.

- 21. SIMes = (1,3-Bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)-4,5-di-hydroimidazoliumtetrafluoroborate

- 22.We hypothesize ligation of the carbamate to the nickel complex directs oxidative addition when PCy3 is employed; see SI Scheme SI4. Comparison of NHC to PR3: Clavier H, Nolan SP. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:841. doi: 10.1039/b922984a.

- 23.Changing PCy3 loading from 20 mol % to 11 mol % does not affect the stereochemical outcome; see SI.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.