Abstract

Background

A debate surrounding multiple sclerosis epidemiology has centred on time-related incidence increases and the need of monitoring. The purpose of this study is to reassess multiple sclerosis incidence in the European Economic Area.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of literature from 1965 onwards and integrated elements of original research, including requested or completed data by surveys authors and specific analyses.

Results

The review of 5323 documents yielded ten studies for age- and sex-specific analyses, and 21 studies for time-trend analysis of single data sets. After 1985, the incidence of multiple sclerosis ranged from 1.12 to 6.96 per 100,000 population, was higher in females, tripled with latitude, and doubled with study midpoint year. The north registered increasing trends from the 1960s and 1970s, with a historic drop in the Faroe Islands, and fairly stable data in the period 1980-2000; incidence rose in Italian and French populations in the period 1970-2000, in Evros (Greece) in the 1980s, and in the French West Indies in around 2000.

Conclusions

We conclude that the increase in multiple sclerosis incidence is only apparent, and that it is not specific to women. Monitoring of multiple sclerosis incidence might be appropriate for the European Economic Area.

Keywords: Incidence, Monitoring, Multiple sclerosis, Time-trends, Surveillance

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, demyelinating disease with frequent worsening episodes denoted as bouts or MS exacerbations, which are characteristic of the so-called relapsing-remitting form (RRMS) and absent in the less common, primary progressive form (PPMS). Despite intensive research over decades and early identification of susceptibility genes [1], its aetiology remains poorly known, with more than 50 susceptibility alleles identified and a considerable proportion of these regulated by Vitamin D [2,3]. Environmental factors, probably acting before adulthood, also appear to be implicated, as reflected by birth-cohort and season-of-birth effects [4,5], selected results of twin studies [6] and changing incidence among populations migrating to environments with different risk [7].

The most lively debate surrounding MS epidemiology at the beginning of the millennium [8-10] could perhaps be said to have centred on time-related increases in MS incidence (MSI), whether genuine or ascertainment-related. Subsequently and due, moreover, to potential post-vaccination incidents or side-effects of immunomodulating therapies, interest in MSI monitoring or surveillance gained wider recognition [11-15]. Several MS registers/studies have developed tools for, e.g., correcting the effects of diagnostic delays or using capture-recapture methods, appropriate for improving the quality and comparability of MSI measurements [16-18]. Design of incidence thresholds and other alarm signals may be problematic, since there is considerable uncertainty worldwide about expected MSI in specific populations for a number of reasons, such as rising trends, seasonality of bouts and validity of diagnostic criteria. The goals and formal components of public health-sponsored surveillance of MS have not yet been defined.

The purpose of this paper was twofold: firstly, it was an attempt to describe and compare MSI reported in recent decades among populations served by medical systems providing regular access to qualified neurological expertise, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and new treatments, potentially covered by publicly-run or -funded national health services, such as those of the European Economic Area (EEA) Member States. The non-EU members of EEA (Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway) have agreed to enact legislation similar to that passed in the EU in the areas of social policy, consumer protection, environment and statistics. Secondly, the paper aimed to explore and describe the historical presence in the above-mentioned survey populations of three, specific, potentially interrelated MS-incidence features: 1) pseudo-periodic or occasional changes in incidence [19-21]; 2) changes in magnitude or shape of the age-specific incidence curve, occasionally reported as bimodal [20,22] and attributed to an increase in incidence among women aged over 40 years [10,23,24]; and, 3) a set of interrelated changes, perceived as a function of calendar time and interpreted as components of potential alarm signals (rising incidence of RRMS; increasing female/male incidence rate ratio and shortened diagnostic delay from clinical onset) [19,25-28].

Methods

Principles for the undertaking of systematic reviews were followed [29].

Study identification

We searched for reports in MEDLINE using “Multiple Sclerosis” and “Incidence”, both as MeSH terms and as TEXT WORDS issued between 1 January 1965 and 31 May 2012. The search yielded 5317 unrepeated documents. Analysis of document titles by two authors, EAC and JPC, searching for issues linked to MSI measurements, enabled identification by mutual agreement for the purposes of perusing the abstract (where available) of 344 of the above-mentioned 5317 documents plus a further six obtained from one of the author’s files. The same two authors then examined the abstracts, identified surveys reporting incidence periods from 1985 onwards, and mutually agreed on 122 of the above-mentioned 350 documents for full-text review. At a later step, the following two criteria sets were used for selection of papers for analysis of age- and sex-specific MSI from 1985 onwards, and time-related changes in MSI in EEA populations including those predating 1985.

Survey selection for studying age- and sex-specific MSI

The quality criteria used for results analyses were: (1) use of diagnostic criteria explicitly designed for MS/MS forms; (2) study incidence period either wholly post-1985 or, alternatively, at least two thirds post-1985 in cases where 1985 was included; (3) provision of age- and sex-specific measurements. Where different periods were covered by different reports for the same geographically-defined population, the most informative (usually the most recent) was selected. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) lack of reference to MS forms included in counts; (2) arbitrarily chosen accrual of ≤30 cases; and, (3) reports in languages other than Danish, English, French, Norwegian, Spanish or Swedish.

Survey selection for reviewing time-trends or time-related changes

The quality criteria applied were different and less strict than those used for age- and sex-specific incidence, and required that: 1) measurements included either crude or age- and sex-adjusted incidence rates for an observation period of, at least, an arbitrary 10-year duration in cases where 1985 was included; 2) explicit MS diagnostic criteria were used; 3) figures were based on clinical onset rather than MS diagnostic periods.

Data-extraction or -completion

Study of age- and sex-specific MSI

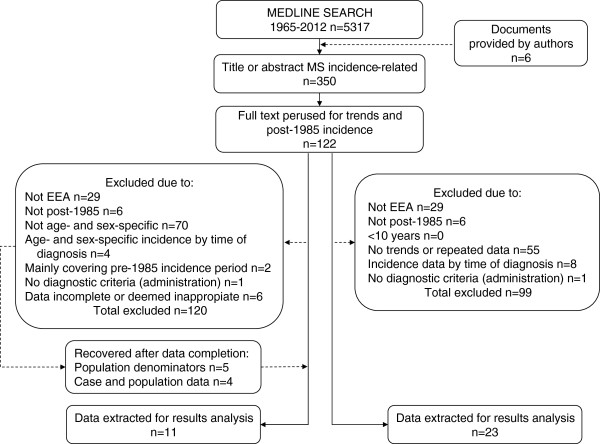

A full-text review by both authors of a number of selected articles on age- and sex-specific MSI measurements in geographically-defined EEA populations suggested that there were insufficient or inadequate reported age-group data to be combined using models, due to one or more of the following factors: being represented only in graphs [30-32]; being incomplete for population groups, i.e., having numerators with zero cases generally in the youngest or oldest age-groups [8,33-37]; containing gross errors in rate calculations, i.e., for incidence in both sexes [38]; pertaining to age-groups that were too wide, selected (in general truncated) or mismatched [39-42]; or corresponding to protracted incidence periods, i.e., 1965-1993, 1968-1997 or 1975-1994, which probably encompassed multiple changes in MS diagnostic policies/traditions that were potentially heterogeneous by age at onset [43-45]. To complete the data, authors of reported surveys were thus contacted in specific instances by JPC via e-mail, correspondence address or telephone number of their institutional affiliations (usually hospital departments). Thus, for reports not yet definitely excluded on the basis of criteria defined in subsection 1.a. above, the authors of 13 surveys [30-35,37-42,46] were requested to furnish such data in a different format, e.g., age at clinical onset instead of age at MS diagnosis, or distribution by age of incident MS case different to that shown. Subsequently, new case-related data were obtained from five surveys [30-32,37,40] or completed with data extracted from graphs, specifically from four of them deemed useful for combination [31,32,37,40]. For 12 surveys, the population structure in new age-groups or complementary demographic data were obtained from the authors or official statistics bodies [8,30-37,40,46,47]. Eight of the 12 surveys for which new data were requested/obtained [8,31,32,34-37,40] fulfilled criteria for inclusion of study results. Since the data from Modena were included in two different reports [36,47], we studied a total of ten age-and sex-specific incidence sets drawn from nine different populations [8,10,31,32,34-37,40,48]. Only two of the eleven surveys finally selected for study provided reported data initially deemed valid for analysis purposes [10,48] (see Figure 1 for a summary description of attrition flow). Reported or obtained numerators and denominators used for analyses are presented in the Table 1.

Figure 1.

Attrition flow towards study selection.

Table 1.

Reported and rearranged data from MS incidence surveys presented in Figure3

|

Study |

|

Men |

Women |

Both |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author Reference | Age group | Cases | Person-years | Rate | Cases | Person-years | Rate | Cases | Person-years | Rate |

| Debouverie 2007

[31] |

0-14 |

0 |

3,070,347 |

0.00 |

7 |

2,911,480 |

0.24 |

7 |

5,981,827 |

0.12 |

| 15-24 |

59 |

2,191,949 |

2.69 |

213 |

2,072,309 |

10.28 |

272 |

4,264,258 |

6.38 |

|

| 25-34 |

154 |

2,236,211 |

6.89 |

445 |

2,199,900 |

20.23 |

599 |

4,436,111 |

13.50 |

|

| 35-44 |

151 |

2,262,937 |

6.67 |

339 |

2,249,492 |

15.07 |

490 |

4,512,429 |

10.86 |

|

| 45-54 |

93 |

1,827,995 |

5.09 |

137 |

1,782,369 |

7.69 |

230 |

3,610,364 |

6.37 |

|

| 55-64 |

21 |

1,458,543 |

1.44 |

32 |

1,542,168 |

2.08 |

53 |

3,000,711 |

1.77 |

|

| 65+ |

2 |

1,680,520 |

0.12 |

5 |

2,584,219 |

0.19 |

7 |

4,264,739 |

0.16 |

|

| Guidetti 1995

[36] |

0-14 |

0 |

449,088 |

0.00 |

0 |

428,838 |

0.00 |

0 |

877,926 |

0.00 |

| 15-24 |

12 |

437,867 |

2.74 |

20 |

424,286 |

4.71 |

32 |

862,153 |

3.71 |

|

| 25-34 |

7 |

429,913 |

1.63 |

25 |

425,059 |

5.88 |

32 |

854,972 |

3.74 |

|

| 35-44 |

9 |

420,283 |

2.14 |

16 |

419,570 |

3.81 |

25 |

839,853 |

2.98 |

|

| 45-54 |

1 |

407,265 |

0.25 |

11 |

409,216 |

2.69 |

12 |

816,481 |

1.47 |

|

| 55-64 |

0 |

384,447 |

0.00 |

2 |

416,345 |

0.48 |

2 |

800,792 |

0.25 |

|

| 65+ |

0 |

414,027 |

0.00 |

0 |

595,139 |

0.00 |

0 |

1,009,166 |

0.00 |

|

| Alonso 2007

[48] |

0-14 |

0 |

1,114,646 |

0.00 |

0 |

1,061,240 |

0.00 |

0 |

2,175,886 |

0.00 |

| 15-24 |

6 |

711,643 |

0.84 |

24 |

700,702 |

3.43 |

30 |

1,412,345 |

2.12 |

|

| 25-34 |

50 |

928,136 |

5.39 |

115 |

926,436 |

12.41 |

165 |

1,854,572 |

8.90 |

|

| 35-44 |

57 |

860,894 |

6.62 |

155 |

837,502 |

18.51 |

212 |

1,698,396 |

12.48 |

|

| 45-54 |

51 |

800,963 |

6.37 |

111 |

780,853 |

14.22 |

162 |

1,581,816 |

10.24 |

|

| 55-64 |

29 |

592,600 |

4.89 |

31 |

596,522 |

5.20 |

60 |

1,189,122 |

5.05 |

|

| 65+ |

5 |

754,786 |

0.66 |

8 |

1,078,718 |

0.74 |

13 |

1,833,504 |

0.71 |

|

| Nicoletti 2005

[32] |

0-14 |

2 |

297,120 |

0.67 |

1 |

281,850 |

0.35 |

3 |

578,970 |

0.52 |

| 15-24 |

10 |

251,490 |

3.98 |

19 |

246,740 |

7.70 |

29 |

498,230 |

5.82 |

|

| 25-34 |

22 |

237,360 |

9.27 |

34 |

240,670 |

14.13 |

56 |

478,030 |

11.71 |

|

| 35-44 |

12 |

205,920 |

5.83 |

25 |

226,150 |

11.05 |

37 |

432,070 |

8.56 |

|

| 45-54 |

7 |

177,620 |

3.94 |

17 |

203,130 |

8.37 |

24 |

380,750 |

6.30 |

|

| 55-64 |

3 |

158,980 |

1.89 |

3 |

193,760 |

1.55 |

6 |

352,740 |

1.70 |

|

| 65+ |

0 |

205,740 |

0.00 |

0 |

295,230 |

0.00 |

0 |

500,970 |

0.00 |

|

| Joensen 2010

[40] |

0-14 |

0 |

125,615 |

0.00 |

0 |

118,653 |

0.00 |

0 |

244,268 |

0.00 |

| 15-24 |

3 |

81,263 |

3.69 |

6 |

69,516 |

8.63 |

9 |

150,779 |

5.97 |

|

| 25-34 |

5 |

74,267 |

6.73 |

9 |

63,934 |

14.08 |

14 |

138,201 |

10.13 |

|

| 35-44 |

6 |

75,305 |

7.97 |

5 |

66,389 |

7.53 |

11 |

141,694 |

7.76 |

|

| 45-54 |

3 |

64,103 |

4.68 |

5 |

55,218 |

9.06 |

8 |

119,321 |

6.70 |

|

| 55-64 |

0 |

49,604 |

0.00 |

1 |

44,487 |

2.25 |

1 |

94,091 |

1.06 |

|

| 65+ |

0 |

59,298 |

0.00 |

1 |

71,896 |

1.39 |

1 |

131,194 |

0.76 |

|

| Sundstrom 2003

[37] |

0-14 |

1 |

255,257 |

0.40 |

1 |

244,079 |

0.40 |

2 |

499,336 |

0.40 |

| 15-24 |

5 |

175,802 |

2.90 |

14 |

169,431 |

8.40 |

19 |

345,233 |

5.60 |

|

| 25-34 |

18 |

179,111 |

10.00 |

32 |

166,142 |

19.20 |

50 |

345,253 |

14.40 |

|

| 35-44 |

16 |

182,644 |

8.70 |

23 |

171,520 |

13.40 |

39 |

354,164 |

10.90 |

|

| 45-54 |

7 |

163,908 |

4.20 |

12 |

157,093 |

7.50 |

19 |

321,001 |

5.90 |

|

| 55-64 |

0 |

126,402 |

0.00 |

4 |

131,128 |

3.10 |

4 |

257,530 |

1.60 |

|

| 65+ |

0 |

189,679 |

0.00 |

0 |

239,325 |

0.00 |

0 |

429,004 |

0.00 |

|

| Granieri 2007

[34] |

0-14 |

0 |

247,388 |

0.00 |

2 |

232,900 |

0.86 |

2 |

480,288 |

0.42 |

| 15-24 |

10 |

282,723 |

3.54 |

17 |

267,370 |

6.36 |

27 |

550,093 |

4.91 |

|

| 25-34 |

21 |

370,041 |

5.68 |

55 |

353,479 |

15.56 |

76 |

723,520 |

10.50 |

|

| 35-44 |

13 |

348,169 |

3.73 |

41 |

349,768 |

11.72 |

54 |

697,937 |

7.74 |

|

| 45-54 |

8 |

336,728 |

2.38 |

18 |

350,939 |

5.13 |

26 |

687,667 |

3.78 |

|

| 55-64 |

1 |

331,387 |

0.30 |

4 |

366,978 |

1.09 |

5 |

698,365 |

0.72 |

|

| 65+ |

0 |

443,139 |

0.00 |

2 |

656,512 |

0.30 |

2 |

1,099,651 |

0.18 |

|

| Granieri 2008

[35] |

0-14 |

0 |

31,856 |

0.00 |

0 |

28,859 |

0.00 |

0 |

60,708 |

0.00 |

| 15-24 |

2 |

25,489 |

7.85 |

4 |

24,735 |

16.17 |

6 |

50,196 |

11.95 |

|

| 25-34 |

3 |

35,513 |

8.45 |

11 |

40,625 |

27.08 |

14 |

76,022 |

18.42 |

|

| 35-44 |

0 |

32,290 |

0.00 |

5 |

33,221 |

15.05 |

5 |

65,509 |

7.63 |

|

| 45-54 |

2 |

27,336 |

7.32 |

2 |

27,582 |

7.25 |

4 |

54,887 |

7.29 |

|

| 55-64 |

1 |

22,396 |

4.47 |

2 |

22,356 |

8.95 |

3 |

44,736 |

6.71 |

|

| 65+ |

0 |

27,157 |

0.00 |

1 |

36,490 |

2.74 |

1 |

63,483 |

1.58 |

|

| Nicoletti 2010

[10] |

0-14 |

0 |

129,630 |

0.00 |

0 |

122,860 |

0.00 |

0 |

252,490 |

0.00 |

| 15-24 |

3 |

103,300 |

2.90 |

13 |

101,785 |

12.77 |

16 |

205,085 |

7.80 |

|

| 25-34 |

10 |

115,110 |

8.69 |

27 |

114,755 |

23.53 |

37 |

229,865 |

16.10 |

|

| 35-44 |

11 |

104,500 |

10.53 |

20 |

114,380 |

17.49 |

31 |

219,880 |

14.10 |

|

| 45-54 |

11 |

98,320 |

11.19 |

8 |

105,025 |

7.62 |

19 |

198,345 |

9.58 |

|

| 55-64 |

4 |

76,320 |

5.24 |

1 |

91,740 |

1.09 |

5 |

168,060 |

2.98 |

|

| 65+ |

0 |

111,475 |

0.00 |

0 |

167,980 |

0.00 |

0 |

275,855 |

0.00 |

|

| Cabre 2009

[8] |

0-14 |

1 |

1,388,049 |

0.07 |

2 |

1,351,144 |

0.15 |

3 |

2,739,193 |

0.11 |

| 15-24 |

6 |

848,215 |

0.71 |

17 |

837,479 |

2.03 |

23 |

1,685,694 |

1.36 |

|

| 25-34 |

8 |

808,481 |

0.99 |

35 |

926,145 |

3.78 |

43 |

1,734,626 |

2.48 |

|

| 35-44 |

7 |

814,933 |

0.86 |

30 |

931,847 |

3.22 |

37 |

1,746,780 |

2.12 |

|

| 45-54 |

2 |

608,781 |

0.33 |

18 |

699,425 |

2.57 |

20 |

1,308,206 |

1.53 |

|

| 55-64 |

1 |

447,677 |

0.22 |

2 |

511,278 |

0.39 |

3 |

958,955 |

0.31 |

|

| 65+ | 0 | 530,373 | 0.00 | 1 | 731,100 | 0.14 | 1 | 1,261,473 | 0.08 | |

Review of time trends or time-related changes

No data were requested from authors for this purpose. Review results for specific MSI, generally at 5- or, alternatively, at >5- [8,10,19,21,27,28,34,36], [41,47,49-56] or 1-year calendar time intervals [31,57,58] were obtained from original reports, disregarding other study-interval durations. Updated data were used for Ferrara [34,43] and Catania [10,32].

Incidence measurements and comparisons

Rates and specific indicators

For each specific survey, age- and sex-adjusted incidences were computed using the European standard population. Female/male (F/M) ratios were obtained, firstly from the number of cases and secondly from stratified analysis (Mantel-Haenszel estimator i.e., F/M M-H). Where not reported, diagnostic delay was calculated from differences between mean or median ages at onset and diagnosis for either incidence or diagnostic periods, if mentioned.

Comparative measurements

Incidence rate ratios were obtained from log-linear models using the binomial distribution. Five analyses were performed using Poisson models. The core analysis was conducted by fitting a global model, in which the independent variables were age-sex, midpoint of study period and categorised diagnostic criteria. F/M ratios were computed from models. Time and latitude trends were described from linear change. Secondary analyses were conducted separately for populations of: both sexes aged below 35 years at onset; both sexes aged ≥35 years at onset; and women or men aged ≥35 years at onset. Calculations were made using the Stata 11 software package. Diagnostic criteria were categorised into the following three variable values: Poser clinically definite and probable; Poser and McDonald or other MRI dependent criteria; and other criteria (McAlpine, Schumacher, and mixed non-MRI related). Midpoint of study period for incidence, latitude in degrees, and F/M M-H obtained from prior analysis were used as continuous variables.

Time-trends

Two independent approaches to time-trends were adopted. Firstly, time-trends from 1985 onwards were studied using mid time points for survey data from models based on ten data sets. Secondly, the reported time series from incidence surveys providing either crude, or age- or age- and sex-adjusted figures for periods encompassing 1985 or after in the EEA were identified for 19 EEA populations in 21 reports. Trends were visually examined from crude or adjusted rates plotted in graphs. When providing the data requested, survey authors occasionally gave their views on the impact had by changes in patient-management traditions on changes in incidence: these views will be referred to below as personal communications.

Results

The above-mentioned 122 documents selected for full-text perusal generated the 37 articles listed in Table 2 and initially considered for potential data requests. Their epidemiological features prior to data completion are shown here mainly for the purposes of assessing possible selection bias and impact of omissions. In general, reported incidences referred to all MS forms, with two surveys providing separate, crude or age- and sex-specific RRMS and PPMS data [54,59]. Surveys reporting incidence for intervals prior to 1985 covered long study periods dating back several decades, e.g., up to 1943 for the Faroes [19,21] and 1955 for Nuoro, Italy [27]. We also included a survey conducted in San Marino, a mini-state not formally belonging to the EEA, with human development indicators similar to or higher than those of EEA countries and specialised medical services shared with Italy [35]. Of the 37 reports, four were used for comparing age-specific incidence only [35,37,40,48], 16 provided data for studying trends [19,21,27,28,41,43,49-58] and seven could be used for both purposes [8,10,31,32,34,36,47]. Ten studies were excluded [24,26,30,33,38,39,42,46], [59,60], four due to incidences calculated from data sets based on age at diagnosis, i.e., explicitly reporting MS diagnoses instead of clinical onsets [30,33,46,60]. The geographical distribution of studies selected for each purpose is depicted in Figure 2. Given the political concept of the EEA, surveys included ethnically, racially and geographically heterogeneous populations.

Table 2.

Epidemiological features of selected studies

| |

Study population |

Study period |

Study |

Sex- and age-specific counts |

Diagnostic criteria |

Other relevant information |

Data obtained from author or external sources (yes/no) |

F/M ratio (incident cases) |

Criteria fulfilled for inclusion in incidence, by age and sex, trend, both or none |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

First author and reference |

Number of years and intervals |

Number of cases (period) |

|

|

Diagnostic delay (DD) in years |

|

|

|

| Mean age at onset/diagnosis | |||||||||

| 1 |

Faroe Islands |

1943-2007 |

81 |

NO |

<1986 Poser CD,CPr |

Mean age at onset |

NO |

1.25 |

Trend |

| |

Denmark |

65 |

|

|

>1986 Poser, |

32y |

|

|

|

| |

Joensen 2011

[19] |

7 |

|

|

McDonald and Thompson |

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

South-west Sardinia |

1958-2007 |

|

YES |

McDonald |

- |

NO |

|

None |

| |

Italy |

50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Cocco 2011

[33] |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

Iceland |

2002-2007 |

136 |

YES |

Poser CD for |

Mean age at diagnosis 36.3y |

YES |

3 |

None |

| Eliasdottir 2011

[46] |

6 |

PPMS |

Mean age at onset 32y |

||||||

| 1 |

|

||||||||

| 4 |

Oppland |

1989-2001 |

148 |

NO |

Poser D and Pr, otherwise NS |

- |

NO |

2.02 |

Trend |

| Norway |

13 |

||||||||

| Risberg 2011

[55] |

3 |

||||||||

| 5 |

Faroe Islands |

1986-2007 |

43 |

YES |

Poser and/or McDonald, for PPMS |

36y at onset |

NO |

1.53 |

Age- and sex-specific incidence |

| Denmark |

22 |

||||||||

| Joensen 2010

[40] |

1 |

||||||||

| 6 |

Ostrobothnia |

1992-2007 |

374 |

NO |

Poser CD |

Mean age at onset 31.7y |

NO |

|

None |

| Finland |

16 |

McDonald CD |

Mean age at diagnosis 35.9y |

||||||

| Krokki 2010

[24] |

1 |

||||||||

| 7 |

Catania |

1975-2004 |

367 (75-04) |

YES |

Poser CD,Cpr,LSPr |

Mean DD 1.4y |

NO |

1.55 |

Both |

| Italy |

30 |

108 (00-04) |

Age at onset increasing with time |

||||||

| Nicoletti 2011

[10] |

6 |

|

|||||||

| 8 |

Cardiff (Wales) |

1985-2007 |

582 |

NO |

Poser and McDonald |

- |

NO |

2.83 |

None |

| United Kingdom |

23 |

(otherwise NS) |

|||||||

| Hirst 2009

[38] |

1 |

||||||||

| 9 |

West Indies |

1992-2007 |

130 |

YES |

Revised McDonald |

Mean age at onset 34.2y |

YES |

4.2 |

Both |

| France |

15 |

||||||||

| Cabre 2009

[8] |

3 |

||||||||

| 10 |

San Marino |

1990-2005 |

33 |

YES |

Poser D,Pr |

Mean DD decreasing with time (1.5 to 0.08y) |

YES |

3.12 |

Age- and sex-specific incidence |

| Italy |

16 |

||||||||

| Granieri 2008

[35] |

1 |

||||||||

| 11 |

Greece 3 regions |

1984-2006 |

834 |

NO |

Poser and McDonald D |

Mean DD 2.62y decreasing with time (3.23 to 1.79y) |

NO |

1.38 |

None |

| Papathanasopoulos 2008

[60] |

23 |

(otherwise NS) |

Mean age at onset 31.41y |

||||||

| 4 | |||||||||

| 12 |

Ferrara |

1965-2003 |

200 (90-03) |

YES |

Poser CD,CP |

Mean DD decreasing with time (1.25 to 0.5y) |

YES |

2.21 |

Both |

| Italy |

39 |

421 (65-03) |

|||||||

| Granieri 2007

[34] |

4 |

||||||||

| 13 |

UK cohort |

1993-2000 |

642 |

YES |

Poser D,Pr, |

- |

NO |

2.24 |

Age- and sex-specific incidence |

| Alonso 2007

[48] |

8 |

McDonald D,Pr |

|||||||

| 1 | |||||||||

| 14 |

Lorraine |

1990-2002 |

1658 |

YES |

Poser D,Pr |

- |

YES |

2.45 |

Both |

| France |

13 |

||||||||

| Debouverie 2007

[31] |

1 |

||||||||

| 15 |

Hordaland |

1953-2002 |

878 |

NO |

Poser |

Mean DD decreasing with time (9.8-0.9y) |

NO |

1.9 |

Trend |

| Norway |

50 |

||||||||

| Grytten 2006

[51] |

10 |

||||||||

| 16 |

Nordland |

1970-1999 |

259 (70-99) |

YES |

Poser |

Mean DD 4.7y |

YES |

1.87 |

None |

| Norway |

30 |

183 (85-99) |

CDPr,,LSDPr |

Mean age at diagnosis 39y |

|||||

| Alstadhaug 2005

[30] |

6 |

||||||||

| 17 |

Catania |

1975-1999 |

155 (90-99) |

YES |

Poser CDPr,LSDPr |

Mean at onset 33.3y |

YES |

1.77 |

Both |

| Italy |

25 |

Mean DD 1.7y |

|||||||

| Nicoletti 2005

[32] |

5 |

||||||||

| 18 |

Sassari |

1965-1999 |

689 |

NO |

Poser |

DD range 13.0-0.9y decreasing with time |

NO |

2.57 |

Trend |

| Italy |

34 |

Age at onset increasing with time |

|||||||

| Pugliatti 2005

[54] |

7 |

||||||||

| 19 |

Monreale City |

1981-2000 |

19 |

YES |

Poser D,Pr |

Mean DD 9.2y |

NO |

- |

Trend |

| Italy |

20 |

||||||||

| Ragonese 2004

[41] |

2 |

||||||||

| 20 |

Evros |

1974-1999 |

56 |

NO |

Poser CD,LSD |

- |

NO |

2.8 |

Trend |

| Greece |

26 |

||||||||

| Piperidou 2003

[53] |

5 |

||||||||

| 21 |

Vasterbotten County |

1988-1997 |

133 |

YES |

Poser |

- |

NO |

1.83 |

Age- and sex-specific incidence |

| Sweden |

10 |

||||||||

| Sundström 2003

[37] |

1 |

||||||||

| 22 |

Finland 3 districts |

1979-1993 |

1066 |

NO |

Poser CD or Lublin et al for PPMS |

Mean age at diagnosis for districts (35.7,39.3,39.7y) |

NO |

1.6 |

None |

| Sumelahti 2003

[59] |

15 |

||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||

| 23 |

Lower (Bajo) Aragon |

1985-2002 |

42 |

NO |

Poser CD,CPr |

DD 2y |

NO |

1.93 |

Trend |

| Spain |

18 |

Mean age at onset 29y |

|||||||

| Modrego 2003

[58] |

1 |

||||||||

| 24 |

Padova |

1980-2000 |

580 |

NO |

Poser |

Decreasing DD with time |

NO |

1.92 |

Trend |

| Italy |

20 |

34y |

|||||||

| Ranzato 2003

[28] |

4 |

||||||||

| 25 |

Iceland |

1951-1999 |

372 |

NO |

Poser |

- |

NO |

1.9 |

Trend |

| Benedikz 2002

[49] |

49 |

||||||||

| 10 | |||||||||

| 26 |

Faroe Islands |

1943-1994 |

54 |

NO |

Poser CD,CPr |

Individual age at onset available |

NO |

- |

Trend |

| Denmark |

52 |

||||||||

| Kurtzke 2001

[21] |

8 |

||||||||

| 27 |

Enna, Sicily |

1986-1995 |

16 |

YES |

Poser |

Mean DD 3y |

NO |

1.28 |

None |

| Italy |

10 |

||||||||

| Grimaldi 2001

[39] |

1 |

||||||||

| 28 |

Oslo |

1972-1996 |

794 |

NO |

Poser CD |

For persons diagnosed 1986-1999 |

NO |

2.38 |

None |

| Norway |

25 |

DD 5.2y |

|||||||

| Celius 2001

[26] |

5 |

Age at diagnosis 38.1y |

|||||||

| 29 |

Nuoro |

1955-1995 |

469 |

YES |

Poser (unspecified), Allison & Millar and Schumacher |

Mean DD 4.61y |

NO |

1.95 |

Trend |

| Italy |

41 |

Mean age at onset 28.5y |

|||||||

| Granieri 2000

[27] |

8 |

||||||||

| 30 |

Alcoi |

1986-1997 |

45 |

NO |

Poser CD,CPr |

- |

NO |

4 |

Trend |

| Spain |

12 |

Mean age at onset 35.1y |

|||||||

| Mallada 2000

[57] |

1 |

||||||||

| 31 |

Troms & Finnmark |

1974-1992 |

139 |

NO |

Rose DPrPs & |

Mean DD 4.5y |

NO |

1.36 |

Trend |

| Norway |

19 |

Poser CD,CPr,LSD |

Mean age at onset/diagnosis available |

||||||

| Gronlie 2000

[50] |

4 |

||||||||

| 32 |

Bagueria city |

1985-1994 |

20 |

YES |

Poser |

Age at diagnosis 34.6y |

NO |

1.86 |

None |

| Italy |

10 |

Mean DD 2.6y |

|||||||

| Salemi 2000

[42] |

1 |

||||||||

| 33 |

North-western Sardinia |

1962-1991 |

277 |

YES |

Poser CD,CPr,LSD,LSPr |

DD range 8.0-1.8y decreasing with time |

NO |

2.46 |

Trend |

| Italy |

30 |

Mean age at onset 27y |

|||||||

| Rosati 1996

[56] |

6 |

||||||||

| 34 |

Ferrara |

1965-1993 |

252 |

YES |

Poser CD,CPr |

DD range 6.1-1.9y decreasing with time |

NO |

2.07 |

Trend |

| Italy |

29 |

Mean age at onset for specific forms |

|||||||

| Granieri 1996

[43] |

6 |

||||||||

| 35 |

More & Romsdal |

1950-1991 |

330 |

NO |

McAlpine |

DD potentially available 6y |

NO |

1.41 |

Trend |

| Norway |

42 |

39.2y |

|||||||

| Midgard 1996

[52] |

8 |

||||||||

| 36 |

Reggio Emilia & Modena |

1970-1990 |

316 (70-90) |

YES |

McAlpine CD,CPr |

- |

YES |

2.01 |

Both |

| Italy |

6 |

105 (85-90) |

Mean age at onset 30.75y |

||||||

| Guidetti 1995

[36] |

4 |

||||||||

| 37 |

Modena |

1970-1990 |

183 (70-90) |

YES |

McAlpine D,Pr |

- |

YES |

1.9 |

Both |

| |

Italy |

6 |

59 (85-90) |

|

|

Mean age at onset 30.8y |

|

|

|

| Cavalletti 1994 [47] | 4 |

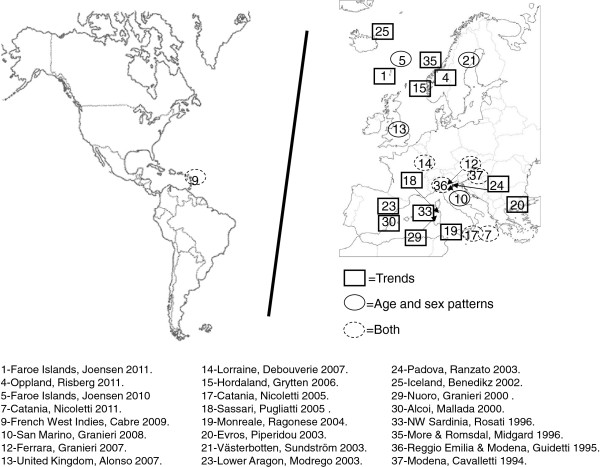

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of MS surveys included in age-specific incidence analysis (top) and time trends (bottom).

Crude and age- and sex- adjusted incidence figures using the European standard population, data on diagnostic delay, latitude and mid time point, F/M M-H, and details of diagnostic criteria for the ten best-quality surveys are listed in Table 3. Effects of adjustment on incidence figures were modest, with crude figures for both sexes ranging from 1.14 to 7.93 per 100,000 person years, and age- and sex-adjusted figures ranging from 1.12 to 7.25 per 100,000 person years, with the extreme levels for the French West Indies and San Marino displaying an almost similar 6- to 7-fold variation. The highest incidence was reported for San Marino (1990-2005), with Poser definite and probable MS diagnostic criteria, and the lowest for the French West Indies (1992-2007), with McDonald criteria. F/M ratios calculated from case numbers ranged from 1.59 to 4.20, and those for F/M M-H had a similar range, 1.68 to 3.79, with figures being lower in the Faroes (1986-2007) and Catania (1990-1999) and higher in the French West Indies. The lowest incidence and highest F/M ratios were seen for the French West Indies. Latitudes varied continentally from 37.3 to 65.0 degrees north, with a 15.2 degree outlier in the French West Indies. The length of diagnostic delay from onset was reported in four surveys, all Italian, ranging from a mean of 21 months in Catania during the period 1990-1999, to a mean of 6.1 months in Ferrara in 2003 and one month (number of patients nor specified) in San Marino in 2005. The more recent the study period, the shorter the diagnostic delay. Poser diagnostic criteria were used in six surveys [10,31,32,34,35,37], McDonald or Poser/McDonald criteria combined in three [8,40,48], and McAlpine’s criteria in the first survey [36]. An aspect that remained unclear was the likelihood of laboratory-supported forms being included in Poser’s forms, denoted by authors as “definite and probable” [8,31,34,35,48], with the proportion of the laboratory-supported probable cases, where specified, being 11% [37]. The F/M ratio did not change with study midpoint using linear regression but showed a modest, albeit statistically significant, decrease when the French West Indies survey was excluded, -2.6% (-4.7%- -0.6%) annually. The F/M ratio decreased significantly with latitude, -2.9% (-3.5%- -2.2%) per degree, and modestly -0.6% (-1.4%- 0.2%) when French West Indian data were excluded (Table 3). Data were deemed too sparse for testing linear associations between incidences and length of diagnostic delays reported in Table 3 (data not shown), or between incidences and F/M figures.

Table 3.

Selected data from surveys with available age- and sex-specific incidence for periods of clinical onset in EEA populations

|

Survey population |

No. cases |

Diagnostic criteria |

Incidence |

Stratified |

F/M |

Diagnostic delay |

Mid time point |

Latitude |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Incidence period |

Crude |

F/M M-H |

ratio |

Months |

Year |

Degrees N |

||||

|

Person/years |

Adjusted |

Mean/median DD |

(1987-2000) |

|||||||

| Reference | Women | Men | Both | |||||||

| Lorraine |

1658 |

Poser D,Pr, (NSO) |

7.68 |

3.26 |

5.51 |

2.50 |

2.45 |

- |

1996 |

49 |

| 1990-2002 |

7.76 |

3.16 |

5.43 |

(2.24-2.77) |

||||||

| 30070439 | ||||||||||

| Debouverie 2007

[31] | ||||||||||

| Reggio Emilia & Modena |

105 |

Mc Alpine D,Pr (NSO) |

2.37 |

0.99 |

1.70 |

2.58 |

2.55 |

- |

1987.5 |

44.28 |

| 1985-1990 |

2.45 |

0.95 |

1.69 |

(1.68-3.97) |

||||||

| 6061343 | ||||||||||

| Guidetti 1995

[36] | ||||||||||

| United Kingdom |

642 |

Poser D,Pr or MacDonald D,Pr (NSO) |

7.42 |

3.44 |

5.47 |

2.26 |

2.24 |

- |

1996.5 |

53.51 |

| 1993-2000 |

7.45 |

3.30 |

5.36 |

(1.91-2.67) |

||||||

| 11745641 | ||||||||||

| Alonso 2007

[48] | ||||||||||

| Catania |

155 |

Poser CDPr,LSDPr |

5.87 |

3.65 |

4.81 |

1.68 |

1.77 |

21 m |

1994.5 |

37.3 |

| 1990-1999 |

6.02 |

3.58 |

4.84 |

(1.21-2.33) |

||||||

| 3221760 | ||||||||||

| Nicoletti 2005

[32] | ||||||||||

| Faroe Islands |

43 |

Poser CD, LSD, or McDonald for one attack (separate criteria for PPMS forms) |

5.51 |

5.21 |

4.32 |

1.82 |

1.59 |

- |

1996.5 |

62.01 |

| 1986-2007 |

5.90 |

5.23 |

4.48 |

(0.99-3.35) |

||||||

| 1019548 | ||||||||||

| Joensen 2010

[40] | ||||||||||

| Västerbotten |

133 |

Poser CDPr, LSDPr |

6.73 |

3.69 |

5.21 |

1.94 |

1.83 |

- |

1992.5 |

65.02 |

| 1988-1997 |

7.23 |

3.72 |

5.43 |

(1.36-2.77) |

||||||

| 2551521 | ||||||||||

| Sundström 2003

[37] | ||||||||||

| Ferrara |

200 |

Poser D,Pr (NSO) |

5.39 |

2.25 |

3.83 |

2.66 |

2.62 |

15.4 m (in 1990) |

1996.5 |

44.5 |

| 1990-2003 |

5.77 |

2.18 |

3.96 |

(1.94-3.63) |

6.1 m (in 2003) |

|||||

| 4937521 | ||||||||||

| Granieri 2007

[34] | ||||||||||

| San Marino |

33 |

Poser D,Pr (NSO) |

11.69 |

3.96 |

7.93 |

2.95 |

3.13 |

18.3 m (in 1990) |

1997.5 |

43.56 |

| 1990-2005 |

10.46 |

3.80 |

7.25 |

(1.32-6.56) |

1 m (in 2005) |

|||||

| 415540 | ||||||||||

| Granieri 2008

[35] | ||||||||||

| Catania |

108 |

Poser CDPr,LSDPr |

8.43 |

5.28 |

6.94 |

1.69 |

1.77 |

17 m |

2002 |

37.3 |

| 2000-2004 |

8.72 |

5.24 |

6.96 |

(1.14-2.49) |

||||||

| 1549580 | ||||||||||

| Nicoletti 2011

[10] | ||||||||||

| French West Indies |

130 |

2005 revised McDonald (NSO) |

1.75 |

0.46 |

1.14 |

3.79 |

4.20 |

- |

2000 |

15.2 |

| 1992-2007 |

1.71 |

0.44 |

1.12 |

(2.45-5.87) |

||||||

| 11434927 | ||||||||||

| Cabre 2009

[8] | ||||||||||

| Beta for F/M M-H in ordinates linear regression |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

| All data sets |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.022 |

-0.029 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(-0.006, 0.05) |

(-0.035, -0.022) |

| (French West Indies excluded) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.026 |

-0.006 |

| (-0.047, -0.006) | (-0.014, 0.002) | |||||||||

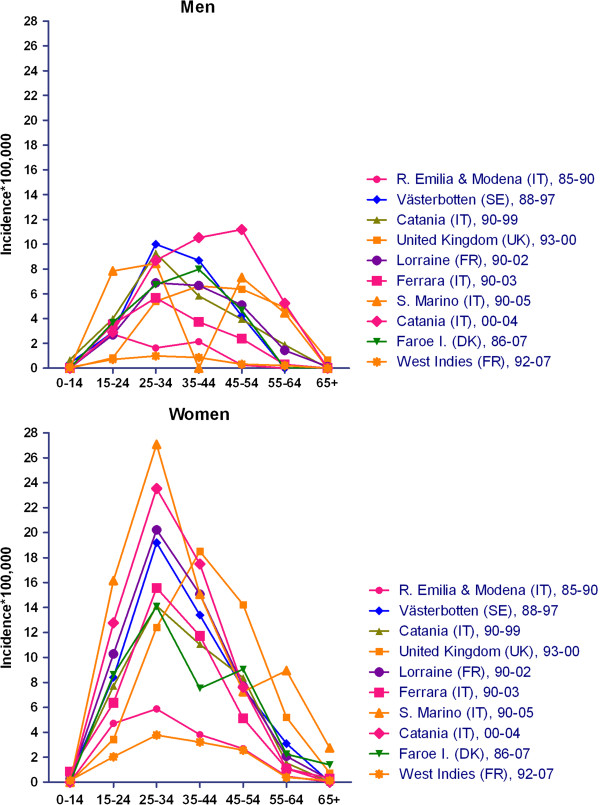

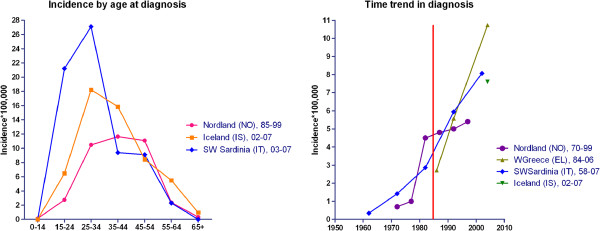

Age- and sex-specific incidences for ten surveys are depicted in Figure 3. In general, incidence among women was nil at ages under 15 (five surveys) and ≥65 years, and low at ages 55-64 years, peaked at 25-34 years in general and at 35-44 years solely in the UK study, frequently reaching values of 20-30 per 100,000. The lowest figures were seen: for the survey conducted in Reggio Emilia-Modena in 1985-1990, using Poser criteria; and in particular, for the recent study conducted in the French West Indies in 1992-2007 using McDonald’s revised criteria. Among men, age-specific incidence was less stable and lower, suggesting a trend to peak at later ages in some recent surveys in the UK and Catania [10,48].

Figure 3.

Age-and sex-specific incidences of selected EEA surveys.

Results from log-linear models are described in Table 4. We used ten data sets from surveys undertaken in different, independent populations, fulfilling selection criteria for the study of age-and sex-specific incidence. Lorraine, a large and well-conducted study, was chosen as reference, and ages 25-34 and 35-44 years at onset were the reference for comparisons when analyses were restricted to ≤34 and ≥35 years respectively. Results were in general similar for the core analysis, women, men, ages below 35 years at onset and ages >35 years at onset, with negligible differences. As seen from the core model, 7-fold differences in RRs were seen, with differences in RRs in Catania, 1.39 (1.01-1.91), Reggio Emilia-Modena, 0.33 (0.24-0.45), and the French West Indies, 0.20 (0.16-0.29) proving statistically significant. Incidence among women was triple that of men 2.9 (1.87-2.57). The mean increase in incidence with time was 9% (4%-15%) per year in both sexes. Incidence was different when measured using MRI-based criteria (McDonald criteria included) in the core model, RR 0.68 (0.55-0.85).

Table 4.

Results from log-linear models (binomial function), OR and 95%CI

| |

|

Core analysis |

Both sexes |

Both sexes |

Women |

Men |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study population, incidence period | All ages both sexes | Age at onset <35y | Age at onset ≥35y | Age at onset ≥35y | Age at onset ≥35y | |

| First author and reference |

Lorraine 1990-2002 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Debouverie 2007

[31] | ||||||

| Reggio Emilia 85-1989 |

0.33 |

0.37 |

0.25 |

0.28 |

0.18 |

|

| Guidetti 1995

[36] |

(0.24-0.45) |

(0.29-0.48) |

(0.17-0.36) |

(0.19-0.42) |

(0.09-0.37) |

|

| UK cohort 1993-2000 |

1.22 |

0.57 |

1.66 |

1.59 |

1.55 |

|

| Alonso 2007

[48] |

(0.94-1.59) |

(0.48-0.66) |

(1.30-2.13) |

(1.28-1.96) |

(1.03-2.35) |

|

| Catania 1990-1999 |

0.98 |

0.90 |

0.87 |

0.84 |

0.90 |

|

| Nicoletti 2005

[32] |

(0.72-1.32) |

(0.72-1.12) |

(0.63-1.20) |

(0.61-1.17) |

0.53-1.50) |

|

| Faroe Islands 86-2007 |

0.94 |

0.83 |

0.91 |

0.80 |

1.02 |

|

| Joensen 2011

[19] |

(0.63-1.39) |

(0.55-1.25) |

(0.57-1.48) |

(0.45-1.45) |

(0.49-2.10) |

|

| Västerbotten 88-1997 |

1.07 |

1.03 |

1.00 |

0.96 |

1.02 |

|

| Sundström 2003

[37] |

(0.79-1.46) |

(0.81-1.32) |

(0.72-1.39) |

(0.68-1.36) |

(0.61-1.70) |

|

| Ferrara 90-2003 |

0.74 |

0.79 |

0.64 |

0.74 |

0.49 |

|

| Granieri 2007

[34] |

(0.55-0.99) |

(0.65-0.97) |

(0.48-0.86) |

(0.55-0.98) |

(0.29-0.81) |

|

| San Marino 90-2005 |

1.44 |

1.43 |

1.19 |

1.34 |

0.81 |

|

| Granieri 2008

[35] |

(0.93-2.23) |

(0.92-2.23) |

(0.66-2.15) |

(0.71-2.54) |

(0.25-2.61) |

|

| Catania 2000-2004 |

1.39 |

1.19 |

1.43 |

1.06 |

2.07 |

|

| Nicoletti 2011

[10] |

(1.01-1.91) |

(0.90-1.57) |

(1.01-2.00) |

(0.72-1.57) |

(1.26-3.38) |

|

| West Indies 1992-2007 |

0.21 |

0.19 |

0.21 |

0.26 |

0.11 |

|

| Cabre 2009

[8] |

(0.16-0.29) |

(0.15-0.25) |

(0.15-0.29) |

(0.19-0.35) |

(0.06-0.22) |

|

| Age-groups |

0-14y |

0.01 |

0.01 |

- |

- |

- |

| (0.008-0.02) |

(0.008-0.02) |

|

|

|

||

| 15-24y |

0.50 |

0.47 |

- |

- |

- |

|

| (0.39-0.64) |

(0.42-0.52) |

|

|

|

||

| 25-34y |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

|

| 35-44y |

0.84 |

- |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

| (0.67-1.04) | ||||||

| 45-54y |

0.56 |

- |

0.66 |

0.61 |

0.71 |

|

| (0.44-0.71) |

|

(0.55-0.78) |

(0.52-0.71) |

(0.52-0.97) |

||

| 55-64y |

0.19 |

- |

0.21 |

0.17 |

0.29 |

|

| (0.14-0.25) |

|

(0.17-0.27) |

(0.14-0.22) |

(0.20-0.44) |

||

| ≥65y |

0.02 |

- |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

|

| (0.01-0.04) |

|

(0.01-0.04) |

(0.01-0.04) |

(0.01-0.06) |

||

| Sex (reference men) |

|

2.19 |

2.81 |

1.96 |

- |

- |

| (1.87-2.57) |

(2.51-3.14) |

(1.67-2.31) |

||||

| Mid time point incidence period * |

|

1.09 |

1.06 |

1.12 |

1.07 |

1.20 |

| (1.04-1.15) |

(1.01-1.12) |

(1.05-1.20) |

(0.99-1.15) |

(1.07-1.34) |

||

| Latitude degrees* |

|

1.04 |

1.03 |

1.05 |

1.04 |

1.06 |

| (1.03-1.05) |

(1.02-1.04) |

(1.03-1.06) |

(1.02-1.05) |

(1.03-1.08) |

||

| Diagnostic criteria* |

Poser |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Other than Poser’s (McAlpine) MRI data not considered |

0.73 |

0.71 |

0.77 |

0.59 |

0.99 |

|

| (0.41-1.30) |

(0.40-1.26) |

(0.35-1.67) |

(0.25-1.41) |

(0.25-3.87) |

||

| McDonald or Poser and MacDonald including MRI evidence of spread |

0.68 |

0.43 |

0.94 |

1.06 |

0.76 |

|

| (0.55-0.85) | (0.35-0.53) | (0.71-1.22) | (0.80-1.41) | (0.49-1.26) |

*Models including the variables indicated in results but not the survey place/time variable.

Complementary analysis revealed some discrepancies. Models for ages ≥35 years revealed the highest incidences in the UK, 1.66 (1.30-2.13), and Catania, 1.43 (1.02-2.61), with an F/M ratio of 1.96 (1.67-2.31), 1/3 lower than those seen for the younger age groups. The analysis of men aged ≥35 years at onset showed the highest, 20% (7%-34%), statistically significant increase in incidence per year, which almost tripled that seen among women of the same age, i.e., 7%. MRI-based diagnostic criteria had the highest impact on populations aged ≤35 years, 0.43 (0.35-0.53). When separate models were adjusted for age and sex, the above-mentioned incidence increased with study midpoint, i.e., ages ≥35 years in both sexes, by 12% (5%-20%) annually, together with a 5% (3%-6%) increase per degree of latitude, present across all age- and sex- or age-groups. The increase per degree of latitude was significant and rose with age and male sex, ranging from 3% for both sexes aged ≤34 years to 6% for men aged ≥35 years.

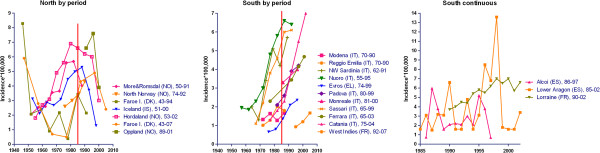

Time series from selected surveys are depicted in Figure 4. Seven reports on Nordic, eight on Italian, and two on Greek and French Caribbean populations covered 5- to 10-year incidence figures for long periods from 1943 to 2007. Three surveys, one French and two Spanish, furnished time-series data for annual counts for the period 1985-2002. In general, MSI increased with: (a) high figures in northern and southern continental populations, reaching four to seven per 100,000 person-years but plotting different shapes, i.e., sharply decreasing in the most recent study period in northern populations (frequently attributed by authors to incomplete case-finding due to diagnostic delay) and yet increasing in Italian populations; and, (b) lower incidences in Greek and French Caribbean populations. Profiles from annual counts were difficult to assess for Alcoi and Lower Aragon (Spain) [57,58] due to unstable data, and clearly increasing for Lorraine (France) [31].

Figure 4.

Time trends of reported MSI in the following EEA populations: (left) Nordic; (centre) Italian, Greek, and French Caribbean; (right) French mainland and Spanish.

The full panorama appears to provide three different geographical and calendar-time related patterns as determined by the increasing rates, ranging from two to seven per million, and lags of approximately 10-20 calendar years. These patterns were as follows: first, northern populations generally exhibited rising incidences in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, with a drop in incidence in the most recent study period, and a complex, different profile with low incidence in the Faroes during the period 1960-1970 [19,49,51,55]; second, Italian populations showed heavily increasing rates from 1-2 to 6-7 per 100,000 during the 1970s, occasionally with a delay of one or more decades, such as the increase in Nuoro which was paralleled 15 years later by Catania and Lorraine, a French mainland population which, since 1990, has registered a magnitude and trend similar to that of Catania; and third, populations in Evros, Greece 1974-1999, where the starting point was the lowest among those studied, 0.66 per 100,000, and the French West Indies 1992-2007, which displayed a rise within a narrow range of 1-2.5 per 100,000 that started in Evros at the end of century and then appeared, after a 15-year delay, in the French West Indies [8,10,27,32,53].

To sum up, in post-1980 periods rates of close on 6-8 per 100,000 were seen in the majority of EEA populations, preceded by increasing and already stable trends in some Nordic (Hordaland, Oppland, Iceland), Italian (Nuoro, Sassari), and French mainland (Lorraine) populations; meanwhile, low but rising figures of 1-3 per 100,000 were still being seen at the end of the century in Greek and Caribbean populations. Where described, variations in incidence were reflected in all age-groups and both sexes. The time-related change (slope) in Nordic populations before the 1980s appeared to be replicated during the 1980s and 1990s by Italian and French populations, and at a later stage, during the 1990s and beyond, by Greek and French Caribbean populations, which solely show rising figures and shorter study periods.

Discussion

The results of this study show that, in recent decades, MSI in EEA populations has been measured using different methods, geographically selected by residence, and has sometimes been reported by age and calendar time at “MS diagnosis”, a health-care variable that is easier to identify than that which it has replaced, i.e., “clinical onset”. Post-1985 results suggest a dynamic picture of MSI, with regular features (peak values for women aged 25-34 years, similar F/M ratios which are higher in the young age strata and youngest populations) and seven-fold variations which are better explained by local changes than by links to latitude (3-fold across 50 degrees latitude, but small if continentally considered) or time (a 2-fold increase per decade). The historical time series suggest increases, initially in the north and more recently in the south, reaching similar levels, 5-7 per 100,000 population, with figures that are still low in Greece and the French Caribbean. These results do not reveal temporal drops in incidence, except for the Faroes, age-specific bimodality or rising incidences in women linked to an increase in the F/M ratio. When it comes to data analysis and interpretation of results, limitations include: infrequent description of temporal relationships between the diagnostic process and end of case-finding periods; lack of systematic assessment of impact of health service innovations on MS diagnosis (not systematically searched for); and cultural-behavioural differences on seeking diagnosis after mild symptom onset.

Selection might partly account for our results, firstly due to the choice of population by EEA neurologists conducting surveys. Secular trend analysis was mainly based on two very different but relatively homogeneous populations and medical services, i.e., Nordic and Italian. This bipolar pattern was not present in post-1985 data, in which Nordic populations were comparatively underrepresented. Interestingly, the large, sevenfold, variation is evident in both data sets, secular and post-1985, and is therefore unlikely to have been biased in the same direction by selection. Selection might have been determined by exclusion of surveys reporting age and time-point at MS diagnosis. A data plot of some surveys rejected due to incidence being calculated by age-at-diagnosis [26,30,33,46,60] indicates that three incidence features, namely, high magnitude, increase in incidence among persons aged ≥35 years and rising time trends, are more clearly revealed when seen from new diagnoses (see Figure 5) than from onsets in Figure 3. This view suggests that the increase in MS diagnoses is higher than the increase in MS onsets. The shortening of MS diagnostic delays in post-1985 surveys, likely restricted to the RRMS form [54], has frequently been described in Italian populations [28,54] but such intervals tend to be more stable in Nordic populations [59]. Diagnostic delay after symptom onset decreased from five years in the mid- or late 1980s in Norway and Italy to two years in the last decade in Spain [26,28,61]. We believe that part of the rise in MS incidence reflects improved access to neurological services at ages considerably later than age at MS onset, with it being impossible, in cases where mild first relapses are neglected, to capture patients who never reach neurological experts. The different age-specific incidence profile and results from complementary analysis showing the highest risk among women aged ≥35 years, suggest that the large UK survey [25] might contain a large proportion of women misclassified by age due to inaccurate reporting of onsets. The use of McDonald’s or theoretically more sensitive mixed criteria [62] was associated with low incidence, a paradox probably explained by the fact that such criteria were applied in survey locations and study periods when MSI was low, such as the French West Indies. The high F/M ratio in the young West Indian population and stable trend are consistent with the stable F/M ratios observed for incident patients registered in Sweden over the period 1946-2005 [63].

Figure 5.

Data based on age at or year of MS diagnosis.

Time-related changes in post-1985 measurements were few, with the most relevant possibly being the rise in incidence among ≥35-year-olds. Bimodality by age at onset, as described in old surveys on black populations in the USA and recently suggested in Newcastle (Australia) for the period 1986-1996 [64], was not in evidence in our data. The explanation for both our and the Newcastle figures might conceivably lie in the capture of silent, mild MS cases by age-differential ascertainment, underlying age-differential access to neurological diagnosis bimodality in old surveys [22,65-67]. The low, extensively studied, incidences in the Faroe Islands, the modest decreasing trend in Hordaland for the 1980-1995 midpoint interval, and the occasional decline registered in Denmark [20] remain unexplained.

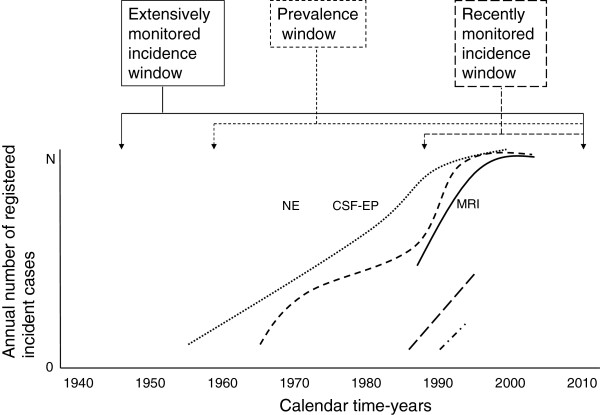

While substantial, several-fold variation in MSI was linked to place and only twofold variation was linked to latitude or time, such variation was not linked to more sensitive, MRI-based diagnostic criteria [33,40]. MS registration in Nordic populations, and more recently in Ferrara or Catania, shows that the magnitude of local change matches recorded international differences across longer periods and affects all age and sex groups. Improvement in diagnostic ascertainment across all ages in recent decades is evident from improved access to neurological expertise, laboratory testing and MRI, and is frequently reported in Nordic and Italian studies. The fact that earlier low incidence persists being low after prolonged survey updates in Ferrara, Catania and Hordaland, may suggest that diagnostic improvement basically affects clinically recent and mildest MS forms. Such ubiquitous factor might explain secular and post-1985 time trends in the EEA. This interpretation is difficult to reconcile with two views held by local researchers claiming a true increase in MSI: first, that suggested by Italian and mainland-based French neuroscientists, whereby the increase is said to be attributable to the biological impact of changes in women’s life-style [10,23,31,44]; second, that relatively restricted to returning continental immigration, reported in the French West Indies as a lagged phenomenon imported from a higher-risk environment [8,68]. Major reasons for rejecting such interpretations or modulating them in favour of better detection in mild cases are: (1) that the increase in MSI among women or older women is, if anything, restricted to single surveys (not seen here), and that changes in EU women's lifestyles (e.g., occupational) were generalised and predated studies on Scandinavian populations not showing such an increase, (http://www.ilo.org); (2) that rising MSI in the French West Indies pertains to particularly severe forms [8,69], thus potentially representing the tip of the iceberg already uncovered in the majority of other surveyed EEA populations, and (3) rising MSI is seen in men. Disregarding potential effects of D Vitamin dietary or childhood hygienic changes, race and latitude, we would prefer to propose that increased population concern about MS symptoms, referral and access to neurological expertise and, recently, to technology acting on stable MSIs might account for the entire EEA pattern, particularly due to the increasing proportion of women active in non-domestic occupational work among those of working age in EEA-surveyed populations. The geographically and time-related decreasing differences in MSI in the EEA by asymptotic trend towards an incidence of 5-7 per 100,000, may suggest that MS appears to behave invariantly with respect to time and space at a stage characterised by improvements in diagnosis and treatment, and by the loss of the natural history due to the widespread use of immune-modulatory treatments that are partly effective and not free of side-effects [70,71]. MS diagnostic functions at EEA might mirror the parallel logarithmic or sigmoid functions outlined in Figure 6. Such pattern defines a framework that is inevitably present in different approaches (surveys, registries, monitoring systems), potentially providing what are apparently diverging but are, in reality, consistent results on different patients. On combining worldwide data from 38 incidence periods reported in 1966-2007, i.e. the global longitudinal approach, Alonso and Hernan [25] describe increasing time-trends for incidence and F/M ratios attenuated after 1980, findings that are consistent with ours. Register-based, calendar-time-limited incident approaches (see the post-1985 window in Figure 6) and prevalence approaches [72] accumulate an increasing proportion of frequently treated cases detected in high-incidence settings.

Figure 6.

Outline of the framework for registry-based MS monitoring on different EEA populations, assuming stable annual MSI (N onsets per year) and MS diagnostic improvement secondary to synergistic effects of improved access to neurological expertise (NE), CSF oligoclonal bands, neurophysiological tests and visual evoked potentials (CSF-EP), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Given the suggested difficulties found in measuring MSI, it would appear that the proposal of a pilot surveillance system active under suspect alarm conditions, similar for instance to those designed and tested for Guillain-Barré syndrome [73], may not be opportune for a number of reasons (lack of reported outbreaks or an expected preventive response, problems managing suspected cases), at least until MSI levels exceed those described for Nordic populations or new aetiological agents are identified. Instead, some of the existing monitoring alternatives appear to be reasonable, subject to being population- rather than hospital-based. Fortunately, there is long experience of monitoring EEA populations.

Conclusions

We conclude that the reported rising incidence of MS in the EEA might be attributable to improved ascertainment and that population-based MS monitoring by selected centres may be useful.

Competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. Enrique Alcalde-Cabero’s work was partly funded by the above-mentioned grant from Biogen Idec.

Authors’ contributions

E Alcalde-Cabero contributed to the design of the methods and protocols, refined and managed the study database, and conducted preliminary tabulations and statistical analyses; J Almazán-Isla supervised data collection and data entry; J. de Pedro-Cuesta conceived the study, coordinated the research team, and collaborated with E Alcalde on the draft of the first manuscript. All authors contributed by commenting on the manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Enrique Alcalde-Cabero, Email: ealcalde@isciii.es.

Javier Almazán-Isla, Email: jalmazan@isciii.es.

Antonio García-Merino, Email: gmerino@meditex.es.

Joao de Sá, Email: jcorreiasa@gmail.com.

Jesús de Pedro-Cuesta, Email: jpedro@isciii.es.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by the fact that a number of authors of reported studies provided supplementary data on the reported numerators and population figures, and revised the results submitted. Accordingly, the authors of this study are most grateful to: Alstadhaug K.B., Norway; Granieri E. and Nicoletti A., Italy; Debouverie M. and Cabre P., France; Sundström P., Sweden; and Joensen P., Faroe Islands, Denmark. Thanks must likewise go Javier Damian and Leszek Stawiarz for invaluable comments, to Marta Valente at Biogen Idec, Lisbon, for support received, and Michael Benedict for his help with the review and revision of the English-language version of the manuscript.

References

- Fogdell A, Olerup O, Fredrikson S, Vrethem M, Hillert J. Linkage analysis of HLA class II genes in Swedish multiplex families with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1997;48:758–762. doi: 10.1212/WNL.48.3.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawcer S, Hellenthal G, Pirinen M, Spencer CC, Patsopoulos NA, Moutsianas L, Dilthey A, Su Z, Freeman C, Hunt SE. et al. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2011;476:214–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranzini SE, Nickles D. Genetics of multiple sclerosis: swimming in an ocean of data. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:239–245. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283533a93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Soderstrom M, Stawiarz L, Link H. Seasonal patterns in optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2000;181:56–64. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(00)00408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin YP, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Lopez-Abente G, Link H. Birth cohort effects in multiple sclerosis. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:252–260. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(02)00278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes CH, Macgregor AJ. Twin studies and the heritability of MS: a conclusion. Mult Scler. 2009;15:661–667. doi: 10.1177/1352458509104592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale CR, Martyn CN. Migrant studies in multiple sclerosis. Prog Neurobiol. 1995;47:425–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabre P. Environmental changes and epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in the French West Indies. J Neurol Sci. 2009;286:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito-Leon J. Are the prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis changing? Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36:148–149. doi: 10.1159/000325368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti A, Patti F, Lo Fermo S, Messina S, Bruno E, Quattrocchi G, Laisa P, Cilia S, Mostile G, Marziolo R. et al. Increasing frequency of multiple sclerosis in Catania, Sicily: a 30-year survey. Mult Scler. 2011;17:273–280. doi: 10.1177/1352458510386995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernan MA, Jick SS, Olek MJ, Jick H. Recombinant hepatitis B vaccine and the risk of multiple sclerosis: a prospective study. Neurology. 2004;63:838–842. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000138433.61870.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flachenecker P, Stuke K. National MS registries. J Neurol. 2008;255(Suppl 6):102–108. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-6019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlgren C, Oden A, Toren K, Andersen O. Multiple sclerosis incidence in the era of measles-mumps-rubella mass vaccinations. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009;119:313–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero S, Batlle J, Bonaventura I, Brieva L, Bufill E, Cano A, Carmona O, Escartin A, Marco M, Moral E. et al. Multiple sclerosis epidemiological situation update: pertinence and set-up of a population based registry of new cases in Catalonia. Rev Neurol. 2010;50:623–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardage C, Persson I, Ortqvist A, Bergman U, Ludvigsson JF, Granath F. Neurological and autoimmune disorders after vaccination against pandemic influenza A (H1N1) with a monovalent adjuvanted vaccine: population based cohort study in Stockholm, Sweden. BMJ. 2011;343:d5956. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sa J, Alcalde-Cabero E, Almazan-Isla J, Sempere A, de Pedro-Cuesta J. Capture-recapture as a potentially useful procedure for assessing prevalence of multiple sclerosis: methodologic exercise using portuguese data. Neuroepidemiology. 2012;38:209–216. doi: 10.1159/000337534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbjerg S, Keiding N, Koch-Henriksen N. Reporting delay and corrected incidence of multiple sclerosis. Stat Med. 1999;18:1691–1706. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19990715)18:13<1691::AID-SIM160>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thygesen LC, Keiding N, Koch-Henriksen N. Evaluating a parametric model to correct multiple sclerosis incidence for reporting delay. Stat Med. 2011;30:896–898. doi: 10.1002/sim.4111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joensen P. Multiple sclerosis: variation of incidence of onset over time in the Faroe Islands. Mult Scler. 2011;17:241–244. doi: 10.1177/1352458510386997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch-Henriksen N, Bronnum-Hansen H, Hyllested K. Incidence of multiple sclerosis in Denmark 1948-1982: a descriptive nationwide study. Neuroepidemiology. 1992;11:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000110900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzke JF, Heltberg A. Multiple sclerosis in the Faroe Islands: an epitome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1–22. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poskanzer DC, Schapira K, Miller H. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in the counties of Northumberland and Durham. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1963;26:368–376. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.26.4.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debouverie M. Gender as a prognostic factor and its impact on the incidence of multiple sclerosis in Lorraine, France. J Neurol Sci. 2009;286:14–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krokki O, Bloigu R, Reunanen M, Remes AM. Increasing incidence of multiple sclerosis in women in Northern Finland. Mult Scler. 2011;17:133–138. doi: 10.1177/1352458510384012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso A, Hernan MA. Temporal trends in the incidence of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Neurology. 2008;71:129–135. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000316802.35974.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celius EG, Vandvik B. Multiple sclerosis in Oslo, Norway: prevalence on 1 January 1995 and incidence over a 25-year period. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8:463–469. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granieri E, Casetta I, Govoni V, Tola MR, Marchi D, Murgia SB, Ticca A, Pugliatti M, Murgia B, Rosati G. The increasing incidence and prevalence of MS in a Sardinian province. Neurology. 2000;55:842–848. doi: 10.1212/WNL.55.6.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranzato F, Perini P, Tzintzeva E, Tiberio M, Calabrese M, Ermani M, Davetag F, De Zanche L, Garbin E, Verdelli F. et al. Increasing frequency of multiple sclerosis in Padova, Italy: a 30 year epidemiological survey. Mult Scler. 2003;9:387–392. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms920oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai M, McCulloch M, Gorman JD, Pai N, Enanoria W, Kennedy G, Tharyan P, Colford JM Jr. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: an illustrated, step-by-step guide. Natl Med J India. 2004;17:86–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alstadhaug KB, Olavsen J, Salvesen R. [Occurrence of multiple sclerosis in Nordland, 1970-1999] Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2005;125:431–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debouverie M, Pittion-Vouyovitch S, Louis S, Roederer T, Guillemin F. Increasing incidence of multiple sclerosis among women in Lorraine, Eastern France. Mult Scler. 2007;13:962–967. doi: 10.1177/1352458507077938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti A, Patti F, Lo Fermo S, Sorbello V, Reggio E, Maimone D, Zappia M, Reggio A. Possible increasing risk of multiple sclerosis in Catania, Sicily. Neurology. 2005;65:1259–1263. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180628.38786.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco E, Sardu C, Massa R, Mamusa E, Musu L, Ferrigno P, Melis M, Montomoli C, Ferretti V, Coghe G. et al. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in south-western Sardinia. Mult Scler. 2011;17:1282–1289. doi: 10.1177/1352458511408754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granieri E, Economou NT, De Gennaro R, Tola MR, Caniatti L, Govoni V, Fainardi E, Casetta I. Multiple sclerosis in the province of Ferrara : evidence for an increasing trend. J Neurol. 2007;254:1642–1648. doi: 10.1007/s00415-007-0560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granieri E, Monaldini C, De Gennaro R, Guttmann S, Volpini M, Stumpo M, Fazio P, Casetta I. Multiple sclerosis in the Republic of San Marino: a prevalence and incidence study. Mult Scler. 2008;14:325–329. doi: 10.1177/1352458507084114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti D, Cavalletti S, Merelli E, Zanoni P, Simonazzi P, Sola P, Solime F. Epidemiological survey of multiple sclerosis in the provinces of Reggio Emilia and Modena, Italy. Neuroepidemiology. 1995;14:7–13. doi: 10.1159/000109772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom P, Nystrom L, Forsgren L. Incidence (1988-97) and prevalence (1997) of multiple sclerosis in Vasterbotten County in northern Sweden. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2003;74:29–32. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst C, Ingram G, Pickersgill T, Swingler R, Compston DA, Robertson NP. Increasing prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis in South East Wales. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2009;80:386–391. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.144667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi LM, Salemi G, Grimaldi G, Rizzo A, Marziolo R, Lo Presti C, Maimone D, Savettieri G. High incidence and increasing prevalence of MS in Enna (Sicily), southern Italy. Neurology. 2001;57:1891–1893. doi: 10.1212/WNL.57.10.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joensen P. Multiple sclerosis incidence in the Faroe Islands 1986-2007. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010;121:348–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragonese P, Salemi G, D’Amelio M, Gammino M, Aridon P, Savettieri G. Multiple sclerosis in southern Europe: Monreale City, Italy. A twenty-year follow-up incidence and prevalence study. Neuroepidemiology. 2004;23:306–309. doi: 10.1159/000080097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salemi G, Ragonese P, Aridon P, Scola G, Saporito V, Conte S, Savettieri G. Incidence of multiple sclerosis in Bagheria City, Sicily, Italy. Neurol Sci. 2000;21:361–365. doi: 10.1007/s100720070051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granieri E, Malagu S, Casetta I, Tola MR, Govoni V, Paolino E, Monetti VC. Multiple sclerosis in Italy. A reappraisal of incidence and prevalence in Ferrara. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:793–798. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550080115019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti A, Lo Bartolo ML, Lo FS, Cocuzza V, Panetta MR, Marletta C, Ciancio MR, Cataldi ML, Patti F, Reggio A. Prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis in Catania, Sicily. Neurology. 2001;56:62–66. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugliatti M, Sotgiu S, Solinas G, Castiglia P, Pirastru MI, Murgia B, Mannu L, Sanna G, Rosati G. Multiple sclerosis epidemiology in Sardinia: evidence for a true increasing risk. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103:20–26. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasdottir OJ, Olafsson E, Kjartansson O. Incidence of multiple sclerosis in Iceland, 2002-2007: a population-based study. Mult Scler. 2011;17:909–913. doi: 10.1177/1352458511402112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalletti S, Merelli E, Cavazzuti M, Guidetti D. Frequency of MS in the province of Modena, 1970-1990. Acta Neurol Scand. 1994;90:377–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb02744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso A, Jick SS, Olek MJ, Hernan MA. Incidence of multiple sclerosis in the United Kingdom : findings from a population-based cohort. J Neurol. 2007;254:1736–1741. doi: 10.1007/s00415-007-0602-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]