Abstract

Background

The aim of the study was to investigate knowledge and use of wild food plants in two mountain valleys separated by Mount Taibai – the highest peak of northern China and one of its biodiversity hotspots, each adjacent to species-rich temperate forest vegetation.

Methods

Seventy two free lists were collected among the inhabitants of two mountain valleys (36 in each). All the studied households are within walking distance of primary forest vegetation, however the valleys differed in access to urban centers: Houzhenzi is very isolated, and the Dali valley has easier access to the cities of central Shaanxi.

Results

Altogether, 185 wild food plant species and 17 fungi folk taxa were mentioned. The mean number of freelisted wild foods was very high in Houzhenzi (mean 25) and slightly lower in Dali (mean 18). An average respondent listed many species of wild vegetables, a few wild fruits and very few fungi. Age and male gender had a positive but very low effect on the number of taxa listed.

Twelve taxa of wild vegetables (Allium spp., Amaranthus spp., Caryopteris divaricata, Helwingia japonica, Matteucia struthiopteris, Pteridium aquilinum, Toona sinensis, Cardamine macrophylla, Celastrus orbiculatus, Chenopodium album, Pimpinella sp., Staphylea bumalda &S. holocarpa), two species of edible fruits (Akebia trifoliata, Schisandra sphenanthera) and none of the mushrooms were freelisted by at least half of the respondents in one or two of the valleys.

Conclusion

The high number of wild vegetables listed is due to the high cultural position of this type of food in China compared to other parts of the world, as well as the high biodiversity of the village surroundings. A very high proportion of woodland species (42%, double the number of the ruderal species used) among the listed taxa is contrary to the general stereotype that wild vegetables in Asia are mainly ruderal species.

The very low interest in wild mushroom collecting is noteworthy and is difficult to explain. It may arise from the easy access to the cultivated Auricularia and Lentinula mushrooms and very steep terrain, making foraging for fungi difficult.

Keywords: Ethnobotany, Ethnomycology, Wild edible plants, Non-timber forest products

Introduction

Chinese culinary culture is renowned for its use of an extremely large number of ingredients. In many parts of China a large number of wild vegetables is still used, both by peasants in remote rural areas and in restaurants, particularly those located in or near national parks and other high biodiversity areas [1-13], making China one of the best examples of a herbophilous country [13,14]. Since antiquity, Chinese scholars have extensively written about the food qualities of wild plants [15]. Research on the potential nutritional qualities of wild food resources and their distribution was carried out in most Chinese agricultural institutions during the 20th century. Although we know much about edible plants, which are used in various parts of China, this knowledge, due to its vast quantity, has still not been properly synthesized [16]. Comparative reviews of the use of wild food resources in different regions of China are also needed. Another interesting issue, little explored, is that of gender and age differences in the use of wild food resources (but see [11,12]).

In the previous paper from this part of the Qinling Mountains the use of wild edible plants and fungi in one relatively isolated mountain valley of the Qinling Mountains was documented [13], giving a detailed list of wild plants used there. As many as 159 species of edible plants and 13 taxa of fungi were recorded. A large proportion of them is still used. The local population has a deep knowledge of these plants and their preparation techniques. Additionally local farmers eat (after special preparation) considerable amounts of Aconitum carmichaeli tubers, a plant regarded as one of the most toxic plants on earth [17]. The aim of this study was to compare data from that valley with the use of wild food plants in the neighbouring valley characterized by easy access to the urban centers of the Shaanxi province. We also wanted to look at age and gender differences in the use of wild plants and fungi in these two places.

Study area

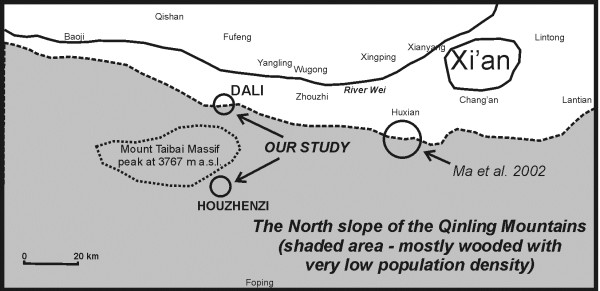

The study area was located in the vicinity of the Taibai Nature Reserve, with the highest peak of northern China in the center of the reserve (Mt Taibai 3767 m a.s.l.). The nature reserve protects a highly diverse flora – from warm temperate (with subtropical elements) to alpine at the top – of over 1700 species, which constitutes approximately 60% of the Qinling range flora [18,19] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The location of the studied valleys.

Two valleys were chosen for the study. The first valley is located in the Heihe National Forest Park, on the southern edge of the Mount Taibai. The National Forest Park (a less strict protection regime) is the southern extension of the Taibai Nature Reserve, and mainly protects species-rich forests. The area is completely covered by ancient forest vegetation and rocky outcrops. The river Heihe valley belongs to the Houzhenzi administrative unit (town, zhen(镇)), with an area of 822 km2. It is a very isolated place, which has vehicular access to the county town of Zhouzhi (where the post-office and schools are located) only via a 2.5 h drive through a winding precipitous gorge, often blocked for days by falling rocks. Until 1962 the valley belonged to Foping county. The whole valley is inhabited by 3,500 people – ca. a thousand in the main settlement of Houzhenzi, and the rest in hamlets scattered in the forest. The studied villages lie between 1000 and 1400 a.s.l. At these altitudes the climate is humid temperate, with daily temperatures in summer oscillating around 20-30°C and winter temperatures around 10°C to – 10°C. The mean annual temperature in Houzhenzi is 8.2°C, with a high rainfall of nearly 1000 mm, out of which 44% is concentrated in the summer months [20,21]. The dominant vegetation is the species-rich Quercus variabilis and Q.aliena var. acuteserrata forest, with an admixture of Pinus tabulaeformis, and many deciduous tree species (e.g. Acer spp., Tilia spp.).

The majority of the local population are subsistence farmers who grow maize, potatoes, wheat and beans. The basic staples of the local population are potato, maize and rice. Each farm usually also has chickens and pigs, so eggs, poultry and cured pig meat (larou) are frequent components of diet as well. Sources of cash income are the orchards of zaopi (Cornus officinalis), walnuts (Juglans regia) and northern Sechuan pepper (Zanthoxylum bungeanum). Digging out medicinal roots and collecting medicinal herbs for wholesale buyers is also a very popular activity. Many peasant families host tourists (many of them hikers), as part of the agritourist farm system called nongjiale (农家乐). A certain influx of tourists in the valley is caused by the fact that it lies on a picturesque and wild foot trail to Mount Taibai.

The second valley, later called Dali valley (after the largest village in it) is located on the northern edge of the Taibai Mt. It is less isolated than the former valley, being easily accessible by car from the county town Meixian, Xi’an and other cities in central Shaanxi. It belongs to the Meixian county, Yingtou administrative unit (town, zhen (镇)), with 11 villages, ca. 20 thousand inhabitants and 202 km2). The actual valley we studied has about 1500 inhabitants and an area of 21 km2. The studied villages lie between 700 and 1200 a.s.l. There is no meteorological data on the climate of the area. The mean temperature from Meixian County weather station (alt. ca. 550 m), 15 km from Dali, is about 12.9°C, so we estimate the mean temperature in Dali valley as 8 – 11°C, depending on elevation and location [22,23]. The dominant vegetation is the species-rich Quercus variabilis and Q.aliena var. acuteserrata forest, with an admixture of Pinus tabulaeformis, and many deciduous tree species (e.g. Acer spp., Tilia spp., Platycladus orentalis, Sorbus spp., Litsea spp.etc.).

The majority of the local population are subsistence farmers who grow maize, potatoes, wheat, and beans. Sources of cash income are walnut orchards (Juglans regia), kiwi fruits (Actinidia chinensis) and northern Sechuan pepper (Zanthoxylum bungeanum). Digging out medicinal roots and collecting medicinal herbs for wholesale buyers is much less important than in the Heihe valley, although a large company buying herbs from all over the central Qinling is located there. A number of stone processing businesses operate in the largest villages. Tourism is little developed and, in contrast to the Houzhenzi valley, there are very few nongjiale in the valley (in contrast to it a neighbouring valley has one of the main entrances to the Taibai Reserve (Red Valley Entrance) and experiences much tourism, but we did not study it due to the large proportion of outsiders who settled there).

Both valleys are inhabited by people of Chinese Han nationality. Most inhabitants are local, although some individuals are outsiders who (or whose families) settled, escaping mid-20th century famines from densely populated parts of Shaanxi and Sichuan, or migrated later due to the socio-cultural situation in China. They speak the Shaanxi dialect of Mandarin (Guanzhong dialect, a form of Zhongyuan dialect). The inhabitants of the Dali valley speak a standard form of the Guanzhong dialect, whereas in the Houzhenzi valley, which is more southern, the influence of the Sichuan dialect is visible [24-26]. A detailed description of the economic status of villages in a neighbouring valley of Qinling Mountains, also applicable to the study area, was given by Neurauter et al. [27].

Methods

The field research was conducted in June and July 2011, as well as in August 2012, using structured freelisting interviews (36 freelists were created in each valley). The listed taxa were identified using transect walks and cross-checking of the gathered herbarium specimens. Participant observation and long semi-structured interviews with key informants were also used to establish the role of wild food in the local communities.

The research was carried out following the code of ethics of the American Anthropological Association [28] and the International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics [29] and general standards of collecting ethnobiological data presented by major ethnobotany textbooks [30-33]. Oral prior informed consent was acquired.

In the Houzhenzi valley the interviewees came from the following villages: Houzhenzi, Diaoyutai, Huaerping, Jiangjiaping and Sanhe. The mean age of participants was 50 (median 49.5, aged from 16 to 83; 20 women and 16 men). In the Dali valley we interviewed people living in: Dalicun, Dawancun, Shapocun, Fufeng, Honghecun, Lijiahecun, Liguancun and Tangyu (21 women and 15 men). The mean age of participants was 58 (median 59, age from 27 to 84). During freelisting we separately asked, which species of wild vegetables (including underground organs), wild fruits and wild mushrooms were used. Making three separate freelists enabled the comparison of the use of these categories and helped elicit answers from the respondents [34,35]. Freelists were made orally and written down on the spot by our team, including the Chinese-script version of the plant/fungi names, which was available to the interviewees.

The study started from a few informants found using the snowball technique, but most interviewees were found by systematic walks through the village, visiting houses and asking the inhabitants if they wanted to take part in the study. We usually interviewed only one person from each household, only occasionally were two people from the same house interviewed, if there were signs that their knowledge differed (e.g. one of the spouses comes from another village, etc.). In a few cases free listing was done in the presence of other family members or neighbours, but one person, delegated as the most knowledgeable, was the main interviewee. Voucher specimens are stored in the Department of Forestry, Northwest A&F University in Yangling.

A Spearman rank correlation matrix was calculated for all the variables studied. Additionally the Mann-Whitney U test was used to test differences between groups (male versus female population, Houzhenzi valley versus Dali valley). Unfortunately the distribution of variables was not normal, even after log-transformation, so we could not perform a multi-factor ANOVA analysis. An open access statistical program, PAST [36,37], was used for statistical analyses.

Results

General figures

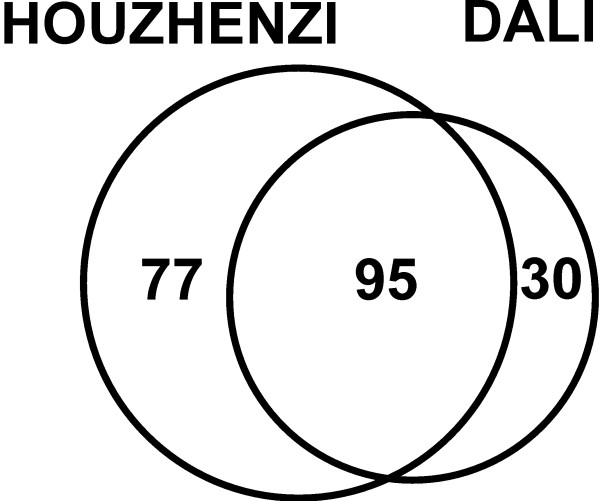

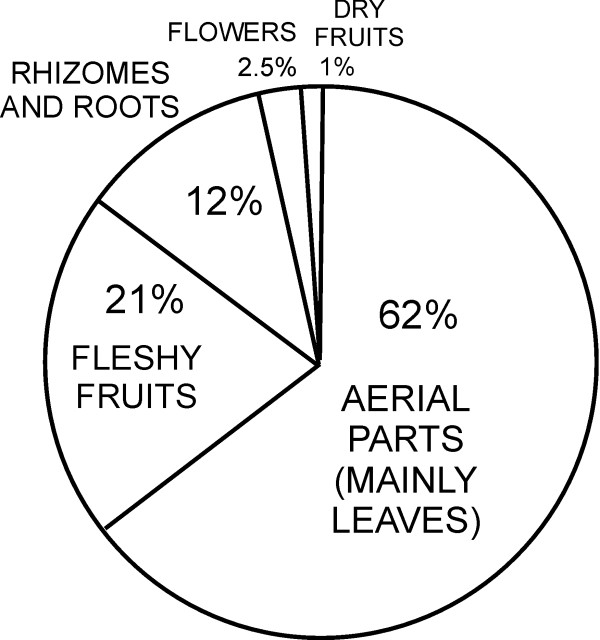

Altogether 167 folk plant taxa with 185 species from 72 families and 17 fungi folk taxa (out of which we identified 12 taxa to genus or species level) were listed by the informants. This includes 126 species of green vegetables, 25 species with edible roots/rhizomes/tubers/bulbs, five species of flowers, 42 with edible fleshy fruits and four of dry fruits/seeds (Figure 2). In Houzhenzi 158 plant species and 14 fungi taxa were mentioned by the informants as eaten at least once in their lifetime, but only 130 plant species and 13 fungi species were confirmed as eaten by more than one person (Tables 1,2 and 3). In Dali 113 plant species and 12 fungi taxa were mentioned by the informants as eaten at least once in their lifetime, but only 77 plant species and 11 fungi taxa were confirmed as eaten by more than one person. There was a considerable overlap in the species listed in both valleys (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The overlap between the number of species of plants and mushrooms used in both valleys.

Table 1.

Rank correlation matrix (Spearman rho coefficient)

| Age | Male gender?=?1 | Houzhenzi valley?=?1 | No of all species | No of vegetable species | No of fruit species | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender?=?1 |

-0.34** |

|

|

|

|

|

| Houzhenzi valley?=?1 |

-0.25* |

0.028 |

|

|

|

|

| No of all species |

0.16 |

0.23 |

0.31** |

|

|

|

| No of vegetable species |

0.26* |

0.27* |

0.35** |

0.89*** |

|

|

| No of fruit species |

-0.025 |

0.029 |

0.089 |

0.68*** |

0.35** |

|

| No of fungi | -0.0009 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.46*** | 0.28* | 0.34** |

*** p?<?0.001; ** p?<?0.01; * p <0.05; values without asterisks are not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Basic features of plant and fungi use in the Qinling mountains

| No. of species used | Frequency of use | Consumption after boiling or stir-frying or in soup | Raw consumption | Drying for further use | Lacto-fermenting | Gender differentiation | Age differentiation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild vegetables |

high |

high |

yes |

no |

frequently |

rarely, more often in the past |

men know slightly more |

low |

| Wild fruits |

intermediate |

low |

no |

yes |

never |

no |

no |

insignificant |

| Wild fungi | low | low | yes | no | very rarely | no | men know slightly more (?) | insignificant |

Table 3.

Wild food species used in the northern slope of the Qinling mountains (plant families given according to APGIII [69])

| Family | Name | Part used for food | Habitat | Frequency in Houzhenzi | Frequency in Dali | Name in Houzhenzi | Name in Dali | Ma | Voucher specimen no. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

VASCULAR PLANTS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Actinidiaceae |

Actinidia chinensis Planch. |

fr |

f |

*** |

*** |

yemihoutao |

野猕猴桃 |

yemihoutao |

野猕猴桃 |

|

193 |

| |

Actinidia polygama Franch. & Sav. |

fr |

f |

|

1 |

|

|

gezaomihoutao |

葛枣猕猴桃 |

|

|

| Amaranthaceae |

Achyranthes bidentata Blume |

ap |

e |

* |

|

niuxi |

牛膝 |

|

|

|

185 |

| |

Amaranthus caudatus L. |

ap |

r |

** |

1 |

tianximi |

天西米 |

ximi |

菥蓂 |

|

|

| |

Amaranthus retroflexus L., A. paniculatus L., A. viridis L. etc. |

ap |

r |

**** |

**** |

hancai, renhancai |

汉菜, 人汉菜, |

hancai, renhancai |

汉菜, 人汉菜, |

|

56, 150 |

| |

Chenopodium album L., Chenopodium giganteum D. Don |

ap |

r |

**** |

*** |

huihuicai |

灰灰菜 |

huihuicai |

灰灰菜 |

x |

49, 160, 216 |

| |

Chenopodium glaucum L. |

ap |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Kochia scoparia (L.) Schrad. |

ap |

e |

* |

yes |

tiesaoba |

铁扫把 |

dudusaozhou |

独独扫帚 |

|

118, 218 |

| Amaryllidaceae |

Allium funckiacfolium Hand.-Mazz. |

ap |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Allium senescens L. |

ap |

e |

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Allium ovalifolium Hand.-Mazz., Allium cf victorialis L. |

ap, u |

e |

* |

* |

gejiu, yejiu |

茖韭, 野韭 |

gejiu |

茖韭 |

|

200 |

| |

Allium paepalanthoides Airy Shaw |

ap, u |

e |

*** |

1 |

tiansuan |

天蒜 |

tiansuan |

天蒜 |

|

27 |

| |

Allium spp. (Allium cf. senescens L.; Allium macrostemon Bunge) |

ap |

e |

**** |

**** |

aijiucai, aisuan, yesuan, yongbaotou, luoerjiu, zongbaotou, yejiucai |

崖韭菜, 崖蒜, 野蒜, 罗儿韭,棕包头, 野韭菜 |

xiaosuan, luoerjiu, yancong, aisuan |

小蒜, 罗儿韭, 岩葱, 崖蒜 |

|

201, 202, 229 |

| |

Allium tuberosum Rottler ex Spreng. |

ap |

e |

|

1 |

|

|

yejiucai |

野韭菜 |

|

227 |

| Anacardiaceae |

Rhus potatninii Maxim. |

ap |

f |

1 |

* |

wubeizishu |

五倍子树 |

wubeizi |

五倍子 |

|

|

| |

Rhus verniciflua Stokes |

ap |

f |

* |

1 |

qishu |

漆树 |

qishuya |

漆树芽 |

|

18 |

| Apiaceae |

Cryptotaenia japonica Hassk. |

ap |

f |

* |

|

yajiuban |

鸭脚板 |

|

|

|

103, 171 |

| |

Daucus carota L. |

ap |

r |

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Ligusticum sinense Oliv. 'Chuanhsiung ' |

ap |

r |

* |

1 |

chuanxiong |

川芎 |

chuanxiong |

川芎 |

|

51 |

| |

Ligusticum levisticum L. |

ap |

r |

|

1 |

|

|

gaoben |

藁本 |

|

|

| |

Oenanthe javanica DC. |

ap |

x |

1 |

** |

beizhe |

背折 |

shuiqincai |

水芹菜 |

x |

65, 213 |

| |

Pimpinella sp. |

ap |

f w |

**** |

|

shuiqincai, shaqincai |

水芹菜, 沙芹菜 |

|

|

|

105, 159 |

| |

Tongoloa silaifolia (de Bois.) Wolff |

ap |

e |

|

1 |

|

|

taibaisanqi |

太白三七 |

|

|

| Araliaceae |

Acanthopanax gracilistylus W.W.Sm. |

ap |

f |

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Aralia chinensis L. |

ap |

f |

** |

** |

cilongpao |

刺龙袍 |

cilongpao, cichuntou, laohanchuizi |

刺龙袍, 刺椿头, 老汉锤子 |

x |

2 |

| Aristolochiaceae |

Asarum himalaicum Hook.f. & Thomson ex Klotzsch |

ap, u |

f |

* |

|

maoxixin |

毛细辛 |

|

|

|

7 |

| |

Asarum sieboldii Miq. |

ap, u |

f |

* |

|

xixin |

细辛 |

|

|

|

24, 163 |

| Asclepiadiaceae |

Cynanchum giraldii Schltr. |

u |

f |

* |

|

geshanxiao |

隔山消 |

|

|

|

133 |

| Asparagaceae |

Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua |

u |

f |

1 |

|

huabeimaoqi |

华北毛七 |

|

|

|

74 |

| |

Polygonatum megaphyllum P.Y.Li and Polygonatum odoratum L. |

u |

f |

* |

|

yuzhu, yuzhushen |

玉竹, 玉竹参 |

|

|

|

31, 34 |

| |

Smilacina japonica A.Gray , Smilacina henryi (Baker) Hara |

ap |

f |

* |

* |

piantoucai |

偏头菜 |

piantoucai |

偏头菜 |

|

6, 129 |

| Asteraceae |

Carduus crispus L. |

ap |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Anaphalis aureopunctata f.flavescens Lingelsh et Borza |

ap |

e |

* |

|

shiqucao |

鼠曲草 |

|

|

|

137 |

| |

Anaphalis margaritacea Benth. & Hook.f. |

ap |

e |

* |

|

qingmingcai |

清明菜 |

|

|

|

116, 161 |

| |

Arctium lappa L. |

ls, u |

x |

* |

|

niubangzi |

牛蒡子 |

|

|

x |

23, 156 |

| |

Artemisia sacrorum Ledeb. |

ap |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Artemisia argyi H.Lév. & Vaniot |

ap |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Artemisia capillaris Thunb. |

ap |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Artemisia subdigitata Mattf. |

ap |

r |

* |

* |

ai |

艾 |

shuihao |

水蒿 |

|

21 |

| |

Cacalia roborowskii (Maxim.) Y.Ling |

ap |

e |

* |

|

xiongerduo |

熊耳朵 |

|

|

|

44 |

| |

Cirsium arvense var. setosum (Willd.) C.A.Mey |

ap |

r |

** |

** |

honghuamiao, ciji |

红花苗, 刺蓟 |

ciji |

刺蓟 |

|

178, 210 |

| |

Cirsium spp. eg Cirsium botryoides Petrak ex Hand.-Mzt. |

ap |

r |

* |

|

xiaoji |

小蓟 |

|

|

x |

62, 101, 117 |

| |

Cirsium segetum Bunge |

ap |

r |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist |

ap |

r |

1 |

|

guangguangcao |

冠罐草 |

|

|

|

141 |

| |

Erigeron acer L. |

ap |

r |

1 |

|

guangguangcao |

冠罐草 |

|

|

|

59 |

| |

Hieracium sp. |

ap |

r |

** |

|

kuma(i)cai |

苦荬菜 |

|

|

|

197 |

| |

Ixeris denticulata (Houtt.) Stebbins |

ap |

r |

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Ixeris chinensis Nakai. |

ap |

f |

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Ixeris sonchifolia Hance |

ap |

r |

*** |

*** |

kumaicai |

苦荬菜 |

kuqu |

|

x |

122 |

| |

Kalimeris pinnatifida (Maxim.) Kitam. |

ap |

e |

* |

|

malantou |

马兰头 |

|

|

|

52, 135, 180 |

| |

Lactuca serriola L. |

ap |

r |

** |

|

xiaobaijiang, xiaokumacai, kumacai |

小苦荬菜, 苦荬菜 |

|

|

|

107 |

| |

Leontopodium japonicum Miq. |

ap |

e |

* |

|

shuqucao |

鼠曲草 |

|

|

|

136 |

| |

Picris hieracioides L. |

ap |

r |

* |

|

kumaicai |

苦荬菜 |

|

|

|

123, 181 |

| |

Saussurea dolichopoda Diels |

ap |

f |

*** |

*** |

kongtongcai, kongxincai |

空筒菜, 空心菜 |

xiangtongcai, kongxincai |

响筒菜, 空心菜 |

|

177, 235 |

| |

Senecio scandens Ham. |

ap |

|

|

|

jiuliming |

九里明 |

|

|

|

|

| |

Sinacalia tangutica (Maxim.) B.Nord. |

u |

e f |

* |

* |

shuiluobo |

水萝卜 |

shuiluobo |

水萝卜 |

|

43, 151 |

| |

Sonchus asper L |

ap |

r |

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Sonchus oleraceus L. |

ap |

r |

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Sylibum marianum L. |

ap |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Taraxacum mongolicum Han.-Mzt |

ap |

r |

** |

** |

pugongying, kumaicai, dakucai |

蒲公英,苦荬菜,大苦菜 |

pugongying |

蒲公英 |

x |

8 |

| Balsaminaceae |

Impatiens notolopha Maxim. |

ap |

f |

* |

|

daolaonnen |

到老嫩 |

|

|

|

179 |

| Begoniaceae |

Begonia sinensis A.DC. |

ap |

f |

* |

|

yikouxie |

一口血 |

|

|

|

138 |

| Brassicaceae |

Capsella bursa-pastoris Medik. |

ap |

r |

*** |

* |

didicai |

地地菜 |

diercai, didicai |

地儿菜, 地地菜 |

x |

25 |

| |

Cardamine engleriana O.E.Schultz. |

ap |

w |

|

1 |

|

|

guangtoushansuimiji |

光头山碎米荠 |

|

|

| |

Cardamine macrophylla Willd. |

ap |

f w |

*** |

**** |

shijiacai |

石夹菜 |

shijiacai |

石夹菜 |

|

20 |

| |

Cardamine spp. (other smaller species e.g. Cardamine flexuosa With., C. hirsuta L.) |

ap |

f |

* |

* |

xiaoshijiacai |

小石夹菜 |

huadidi, huadier |

花地地(small caidamine) |

|

228 |

| |

Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl |

ap |

e |

** |

|

yinchen, mihao |

因陈 , 米蒿 |

|

|

|

142 |

| |

Rorippa montana Small |

ap |

r |

* |

** |

manjingcai, lalacai |

蔓茎菜, 辣辣菜 |

lalacai, lazicai |

辣辣, 辣子菜 |

x |

234 |

| |

Rorippa indica L. |

ap |

r |

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Thlaspi arvense L. |

ap |

r |

*** |

* |

jidanhuang |

鸡蛋黄 |

kugen |

苦根 |

|

10, 228 |

| Campanulaceae |

Adenophora spp. (Adenophora capillaris Hemsl., Adenophora polyantha Nakai) |

ap, u |

e |

*** |

*** |

naijiangcai |

奶浆菜 |

naiercai, nainaicai |

奶儿菜, 奶奶菜 |

|

134, 198, 199, 226 |

| Caprifoliaceae |

Lonicera standishii Carr. |

fr |

f |

* |

** |

kutangpao |

苦糖泡 |

yangnaizi, kutangpao |

羊奶, 苦糖泡 |

|

26 |

| |

Sambucus williamsii Hance |

ap |

f |

1 |

1 |

jiegumu |

接骨木 |

shuhuacai |

树花菜 |

|

47 |

| |

Viburnum sargentii Koehne |

fr |

f |

1 |

|

[no name] |

|

|

|

|

99 |

| Caryophyllaceae |

Arenaria serpyllifolia L. |

ap |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Lychnis senno Siebold & Zucc. |

ap |

e |

* |

|

honghuacai |

黄花菜 |

|

|

|

57, 186 |

| |

Silene conoidea L. |

ap |

r |

* |

** |

maipiancai |

麦片菜 |

maihuaping |

麦花瓶 |

x |

140 |

| |

Stellaria media (L.) Vill. |

ap |

r |

* |

|

eerchang |

鹅儿肠 |

|

|

|

33, 152 |

| |

Vaccaria segetalis (Neck.) Garcke |

ap |

r |

|

1 |

|

|

pangwawa |

胖娃娃 |

|

|

| Celastraceae |

Celastrus orbiculatus Thunb. |

ap |

f |

**** |

*** |

baiwanye |

白蔓叶 |

baiwanye |

白蔓叶 |

|

17 |

| |

Euonymus alatus (Thunb.) Siebold |

fr |

f |

1 |

1 |

bashu, bamu |

巴树, 巴木 |

bamu |

巴木 |

|

|

| |

Parnassia wightiana Wall. |

ap |

f |

1 |

|

xinyecao |

心叶草 |

|

|

|

147 |

| Cephalotaxaceae |

Cephalotaxus sinensis (Rehder & E.H.Wilson) H.L.Li |

fr |

f |

* |

1 |

baigeiguo, bizishu, shuibai, sunguo |

白盖果,篦子树,水柏,松果 |

sanjianshanguo |

三尖杉果 |

|

14, 164 |

| Commelinaceae |

Commelina communis L. |

ap |

r |

* |

|

danzhuye, zhuyecao, miandazi |

淡竹叶,竹叶草,面鞑子 |

|

|

|

106, 158 |

| Convallariaceae |

Tricyrtis macropoda Miq. |

ap |

f |

*** |

*** |

huangguacai |

黄瓜菜 |

huangguacai |

黄瓜菜 |

|

4, 176 |

| Convolvulaceae |

Calystegia hederacea Wall. |

ap |

r |

|

* |

|

|

dawanhua, labahua |

打碗花, 喇叭花 |

x |

|

| |

Cuscuta cf chinensis L. |

ap |

e |

|

1 |

|

|

wugencao |

无根草 |

|

|

| Cornaceae |

Cornus kousa Bürger ex Miq. |

fr |

f |

*** |

* |

shizao |

石枣 |

shizaozi, yelizhi |

石枣子, 野荔枝 |

|

16, 165 |

| Corylaceae |

Corylus heterophylla Fisch. ex Besser |

fr |

f |

* |

1 |

zhenzi, maoli, maolizishu, |

榛子, 毛栗子树 |

zhenzi |

榛子 |

|

15, 167 |

| Crassulaceae |

Sedum aizoon L., S. sarmentosum Bunge, pampaninii Raym.-Hamet, S. lineare Thunb. |

ap |

e |

** |

** |

gouyaban, gouzacai, machijie, dabusi, chuipencao |

狗牙瓣, 打不死 |

shitouya, gouyacai, manaocai |

石头芽, 狗牙菜, 玛瑙菜 |

|

75, 131, 120, 127, 153, 192, 222 |

| |

Sedum amplibracteatum K.T.Fu |

ap |

f |

*** |

*** |

huaqiaoman, lazimiao, lajiaomiao, yelacai |

花荞蔓, 野辣子苗苗, 辣椒苗, 叶辣菜 |

lajiaomiao, lalacai, lazicai, yelazi |

辣椒苗, 辣子菜, 野辣子 |

|

168, 182 |

| |

Sedum verticillatum L. |

ap |

e |

|

1 |

|

|

jingtiansanqi |

景天三七 |

|

|

| Cucurbitaceae |

Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino |

ap |

e |

1 |

|

jiaogulan |

绞股蓝 |

|

|

|

no |

| Dennstaedtiaceae |

Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn |

ap, u |

x |

**** |

**** |

juecai, juegen, longzhua |

蕨菜, 蕨根, 龙爪菜 |

yangjuecai, yangjuegen |

羊蕨菜, 羊蕨根 |

x |

9, 214 |

| Dioscoreaceae |

Dioscorea batatas Decne. |

u |

f |

* |

* |

shanyao |

山药 |

yeshanyao |

野山药 |

|

53, 191, 209 |

| Dryopteridaceae |

Cyrtomium fortunei J.Sm. |

ap |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

unidentified fern cf. Dryopteridaceae |

ap |

f |

1 |

|

xiaojitoucai |

小鸡头菜 |

|

|

|

111 |

| Ebenaceae |

Diospyros lotus L. |

fr |

x |

|

* |

|

|

shishu, junqianzi |

柿树, 君迁子 |

|

|

| Eleagnaceae |

Elaeagnus umbellata Thunb. |

fr |

e |

*** |

1 |

yangnaizi, niunaizi |

羊奶子, 牛奶子 |

jianzi |

剪子 |

|

29, 232 |

| |

Hippophae rhamnoides L. |

fr |

x |

|

1 |

|

|

xiaoguoshaji |

小果沙棘 |

|

|

| Ericaceae |

Pyrola decorata Andres |

ap |

f |

* |

|

hongru, shoucha |

红茹,寿茶 |

|

|

|

68 |

| |

Pyrola rotundifolia L. |

ap |

f |

* |

|

bairu, shoucha |

白茹,寿茶 |

|

|

|

69 |

| Fabaceae |

Cercis chinensis Bunge |

ap |

f |

|

1 |

|

|

momoye |

馍馍叶 |

|

208 |

| |

Kummerovia stipueacea (Makim.) Makino |

ap |

e |

|

|

|

|

qiabuqi |

掐不齐 |

|

|

| |

Medicago sativa L. |

ap |

r |

* |

|

muxicai |

苜蓿菜 |

|

|

|

54 |

| |

Pueraria lobata (Willd.) Ohwi |

u |

e |

** |

* |

gegen |

葛根 |

gegen |

葛根 |

|

|

| |

Robinia pseudoacacia L. |

ap |

f |

* |

1 |

huaihua |

槐花 |

huaihua |

槐花 |

x |

40 |

| |

Vicia cracca L. |

ap |

r |

* |

|

yewandoujian |

野豌豆尖 |

|

|

|

3, 71 |

| |

Vicia sp. |

ap |

r |

|

1 |

|

|

maoshaozi |

毛苕子 |

|

|

| Fagaceae |

Castanea mollissima Blume |

fr |

f |

** |

** |

yemaoli, yebanli |

野毛栗, 野板栗 |

yemaoli, yebanli |

野毛栗, 野板栗 |

|

130 |

| |

Quercus variabilis Blume |

fr |

f |

1 |

|

xiangzishu |

橡子树 |

|

|

|

|

| Grossulariaceae |

Ribes glaciale Wall. |

fr |

f |

1 |

|

[no name] |

|

|

|

|

37 |

| Helwingiaceae |

Helwingia japonica (Thunb.) F.Dietr. |

ap |

f |

**** |

**** |

yeshanghua |

叶上花 |

yeshanghua, yeshanhua |

叶上花, 叶扇花 |

x |

22, 175 |

| Juglandaceae |

Juglans cathayensis Dode |

fr |

f |

** |

** |

yehetao |

野核桃 |

yehetao |

野核桃 |

|

|

| Lamiaceae |

Caryopteris divaricata Maxim. |

ap |

f |

**** |

1 |

choulaohan, laohanxiang |

臭老汉/老汉香 |

choulaohan |

臭老汉 |

|

109 |

| |

Clerodendrum trichotomum Thunb. |

ap |

f |

* |

|

choumudan, choulaohan |

臭牡丹,臭老汉 |

|

|

|

11 |

| |

Lycopus lucidus Turcz. ex Benth. |

ap |

e |

* |

|

yebaicai, zelan |

野白菜,泽兰 |

|

|

|

98 |

| |

Mentha haplocalyx Briq. |

ap |

e |

1 |

|

bohe, yuxiangcao |

薄荷,鱼香草 |

|

|

|

114 |

| |

Stachys affinis Bunge |

u |

r |

* |

|

diguniu |

地牯牛 |

|

|

|

67, 157 |

| Lardizabalaceae |

Akebia trifoliata (Thunb.) Koidz. |

fr |

f |

*** |

**** |

bayuegua, bayuezha |

奶浆菜, 八月炸 |

bayuegua, bayuezha |

奶浆菜, 八月炸 |

|

119 |

| |

Decaisnea fargesii Franch. |

fr |

f |

*** |

*** |

maoshigua, yexiangjiao |

猫屎瓜, 野香蕉 |

yexiangjiao, maoshigua, maoershi |

野香蕉, 猫屎瓜, 猫儿屎 |

|

173 |

| Liliaceae |

Hemerocallis spp. (Hemerocallis dumortierii C.Morren, Hemerocallis fulva L.) |

fl |

e |

** |

* |

yehuanghua |

野黄花 |

yehuanghua |

野黄花 |

|

42, 139 |

| |

Lilium brownii F.E.Brown ex Spae |

u |

f |

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Lilium giganteum Wall. |

u |

w,f |

** |

|

shuibaihe |

水百合 |

|

|

|

35 |

| |

Lilium longiflorum Thunb. |

u |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| |

Lilium lancifolium Thunb. (as L. tigrinum) |

u |

x,w |

** |

|

yebaihe |

野百合 |

|

|

|

64, 124, 184 |

| Linnaeaceae |

Abelia engleriana Rehder |

ap |

f |

*** |

* |

shenxiandoufu |

神仙豆腐 |

shenxiandoufu |

神仙豆腐 |

|

36 |

| Malvaceae |

Grewia biloba G.Don. Var. Parviflora (Bge) Hand.-Mzt. |

fr |

e |

|

1 |

|

|

gebengbeng |

咯嘣蹦 |

|

|

| |

Malva sinensis Cav. |

if |

r |

1 |

1 |

dawanhua |

打碗花 |

yejinkui |

野锦葵 |

|

162, 221 |

| Meliaceae |

Toona sinensis (Juss.) M.Roem. |

ap |

e |

**** |

**** |

xiangchun |

香椿 |

xiangchun |

香椿 |

x |

5 |

| Menispermaceae |

Cocculus trilobus (Thunb.) DC. |

ap |

x |

|

1 |

|

|

heimanye |

黑蔓叶 |

|

233 |

| Moraceae |

Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) Vent. |

ap, fl |

r |

* |

* |

goushuguo, gouye |

构树果,构 叶 |

goutao |

构桃 |

x |

132 |

| |

Morus australis Poir. |

fr |

f |

* |

|

sangpao, sangshu |

桑泡,桑树 |

|

|

|

45 |

| Onocleaceae |

Matteucia struthiopteris (L.) Tod. |

ap |

x |

**** |

**** |

jitoucai |

鸡头菜 |

jiwacai, jiercai |

鸡娃菜, 鸡儿菜 |

|

46, 174, 220 |

| Orchidaceae |

Bletilla striata Rchb.f. |

u |

f |

1 |

|

baiji |

白芨 |

|

|

|

206 |

| |

Gastrodia elata Blume |

u |

f |

|

1 |

|

|

tianma |

天麻 |

|

|

| Oxalidaceae |

Oxalis spp. (O. griffithii Edgew. & Hook.f., O. corniculata L.) |

ap |

f r |

* |

1 |

suancao, suancai, suansuancao |

酸草,酸菜,酸酸草 |

suanjiji |

酸唧唧 |

|

13, 55, 183 |

| Penthoraceae |

Penthorum chinense Pursh. |

ap |

f |

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| Phytolaccaceae |

Phytolacca esculenta Van Houtte |

ap, u, fr |

r |

|

* |

|

|

jiangliusheng |

江柳绳 |

x |

212 |

| Plantaginaceae |

Plantago asiatica L. |

ap |

r e |

* |

|

kaimenye, cheqiancao, cheqianzi |

开门叶,车前草,车前子 |

|

|

|

1, 149 |

| |

Veronica didyma Tenore |

ap |

r |

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| Poaceae |

unidentified Bambusae |

ap |

f |

1 |

|

zhusun |

竹笋 |

|

|

|

|

| Polygonaceae |

Fagopyrum gracilipes (Hemsl.) Dammer |

ap |

r |

1 |

|

yeqiaomai, qiaomaimiao |

乔麦苗 |

|

|

|

143 |

| |

Polygonum aviculare L. |

ap |

r e |

1 |

1 |

bianxu |

萹蓄 |

bianxucai |

萹蓄草 |

|

63, 219 |

| |

Polygonum ciliinerve (Nakai) Ohwi |

u |

e |

* |

|

qiaomaitou |

荞麦头 |

|

|

|

|

| |

Rumex crispus L. |

ap |

e |

** |

1 |

niushetou, yedahuang |

牛舌头,野大黄 |

luerduo |

驴耳朵 |

|

66 |

| Portulaccaceae |

Portulacca oleracea L. |

ap |

r e |

|

1 |

|

|

machixian |

马齿苋 |

x |

|

| Primulaceae |

Lysimachia hemsleyana Maxim. ex Oliv. |

ap |

e |

1 |

|

guoluhuang |

过路黄 |

|

|

|

144 |

| Ranunculaceae |

Aconitum carmichaelii Debeaux (more often cultivated) |

u |

x |

1 |

* |

wuyao |

乌药 |

wuyao |

乌药 |

|

50, 155 |

| Rhamnaceae |

Berchemia sinica Schneid. |

fr |

f |

* |

|

yaguteng |

亚古藤,勾儿茶 |

|

|

|

121 |

| |

Hovenia dulcis Thunb. |

fr |

f |

|

1 |

|

|

guaizao |

拐枣 |

|

|

| |

Zizyphus jujuba var. spinosa (Bunge) Hu |

fr |

e |

1 |

|

|

|

shanzao |

山栆 |

|

|

| Rosaceae |

Crataegus hupehensis Sarg. |

fr |

f |

* |

** |

yeshanzha |

野山楂 |

yeshanzha, mianli, mianlizi |

野山楂, 面梨, 面梨子 |

|

|

| |

Fragaria spp. (Fragaria corymbosa Losinsk., Fragaria pentaphylla Losinsk.) |

fr |

e |

*** |

* |

caomei, dipao, didipaoxiangpao |

草莓, 地泡, 地地泡, 香泡 |

caomei, yecaomei |

草莓, 野草莓 |

|

58, 169, 170 |

| |

Malus prunifolia (Willd.) Borkh. |

fr |

f |

|

1 |

|

|

qiuzi |

秋子 |

|

225 |

| |

Potentilla indica (Andrews) Th.Wolf |

u |

r e |

|

* |

|

|

shemei |

蛇莓 |

|

217 |

| |

Potentilla sp. |

ap |

r |

* |

|

guanyincha |

观音茶 |

|

|

|

115 |

| |

Prunus armeniaca L. |

fr |

x |

** |

** |

yexing |

野杏 |

yexing |

野杏 |

|

|

| |

Prunus canescens Bois, P. pilosiuscula Koehne |

fr |

f |

** |

|

yeyingtao |

野樱桃 |

|

|

|

39 |

| |

Prunus davidiana Franch. |

fr |

x |

1 |

|

shantao |

山桃 |

|

|

|

|

| |

Prunus cfr polytricha Koehne |

fr |

f |

* |

|

chuantao |

川桃 |

|

|

|

28 |

| |

Prunus persica (L.) Batsch |

fr |

f |

** |

*** |

yetaozi |

野桃子 |

yetaozi |

野桃子 |

|

38 |

| |

Prunus salicina Lindl. |

fr |

x |

*** |

*** |

yelizi, zemaili, huolizi, huoli, yemaili |

野李子, 火李子, 火李, 野麦李 |

yelizi, kuli, huoli |

野李子, 苦李, 火李 |

|

187 |

| |

Prunus tomentosa Thunb. |

fr |

f |

|

*** |

|

|

yeyingtao, maoyingtao, maotao |

野樱桃, 毛樱桃, 毛桃 |

|

224 |

| |

Pyrus xerophila T.T.Yu |

fr |

e x |

*** |

** |

yeli, mali, shanli |

野梨, 麻梨, 山梨 |

yeli, mali |

野梨, 麻梨 |

|

|

| |

Pyracantha fortuneana (Maxim.) H.L.Li |

fr |

e |

1 |

|

jiubingliang |

救兵粮 |

|

|

|

|

| |

Rosa omeiensis Rolfe |

fr |

e |

1 |

|

cishiliu |

刺石榴 |

|

|

|

|

| |

Rosa sp. |

ap |

f |

* |

|

cimeihua |

刺玫花 |

|

|

|

110 |

| |

Rubus spp. |

fr |

e x |

*** |

* |

duanyangpao, xuangouzi |

端阳泡, 悬钩子 |

meizi |

莓子 |

|

|

| |

Rubus coreanus Miq. |

fr |

e |

** |

|

cipao, dipao, fupenzi |

刺泡, 地泡,覆盆子 |

|

|

|

30 |

| |

Rubus flosculosus Focke |

fr |

e |

** |

|

caizipao |

菜子泡 |

|

|

|

195 |

| |

Rubus pungens Cambess. |

fr |

e x |

** |

|

huangcipao |

黄刺泡 |

|

|

|

61 |

| Rubiaceae |

Galium aparine L. |

ap |

r |

|

1 |

|

|

ranwawa |

然娃娃 |

|

|

| Rutaceae |

Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim. |

ap, fr |

f |

* |

1 |

yehuajiao |

野花椒 |

yehuajiao |

野花椒 |

|

no |

| Sabiaceae |

Sabia shensiensis H.Y.Chen |

ap |

f |

* |

|

qingtengcai, tengercai |

青藤菜, 藤儿菜 |

qingtengwan |

青藤蔓 |

|

166 |

| Salicaceae |

Salix cf babylonica L. |

ap |

e |

|

1 |

|

|

liushu |

柳树 |

|

|

| Santalaceae |

Buckleya henryi Diels |

fr |

f |

|

* |

|

|

mainhuli, mimianwong |

面核梨, 米面翁 |

|

231 |

| Saururaceae |

Houttuynia cordata Thunb. |

ap |

r |

|

1 |

|

|

yuxingcao |

鱼腥草 |

x |

|

| Saxifragaceae |

Bergenia scopulosa T.P.Wang |

ap |

w |

1 |

|

yebaicai |

野白菜 |

|

|

|

|

| |

Chrysosplenium biondianum Engl. |

ap |

f |

*** |

*** |

hongjincai |

红筋菜 |

hongjincai |

红筋菜 |

|

188 |

| |

Chrysosplenium sinicum Maxim. |

ap |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

| Schisandraceae |

Schisandra sphenanthera Rehder & E.H.Wilson |

fr |

f |

**** |

**** |

wuweizi |

五味子 |

wuweizi |

五味子 |

|

48, 196 |

| Solanaceae |

Physalis alkekengi L. |

ap |

r |

|

* |

|

|

guajindeng, denglonghuacai |

挂金, 灯笼花菜 |

|

215 |

| |

Solanum nigrum L. |

ap |

r |

1 |

* |

suanjiang |

酸浆 |

heilaopo, longkai |

黑老婆 |

x |

70, 211 |

| Staphyleaceae |

Staphylea bumalda DC., S. holocarpa Hemsl. |

ap, fl |

f |

**** |

|

shuhuacai |

树花菜 |

|

|

|

12, 189, 190 |

| Ulmaceae |

Ulmus bergmanniana C.K.Schneid., Ulmus propinqua Koidz. |

ap, b, if |

f e |

** |

* |

yushu |

榆树 |

yushu |

榆树 |

x |

32, 60 |

| Urticaceae |

Boehmeria gracilis C.H.Wright |

ap |

x |

* |

|

honghema |

红河麻 |

|

|

|

128, 194 |

| |

Boehmeria tricuspis Makino |

ap |

x |

* |

|

hema |

河麻 |

|

|

|

76 |

| |

Pilea mongolica Wedd. |

ap |

f |

* |

|

daolaonen |

到老嫩 |

|

|

|

207 |

| |

Urtica fissa E.Pritz. ex Diels |

ap |

x |

* |

|

baihema |

白河麻 |

|

|

|

41 |

| Violaceae |

Viola cf. grypoceras A.Gray |

ap |

r |

1 |

|

didingcao |

地丁草 |

|

|

|

145 |

| Vitaceae |

Vitis ficifolia Bunge |

fr |

f |

*** |

*** |

yeputao |

野葡萄 |

yeputao |

野葡萄 |

|

19 |

| |

FUNGI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Auriculariaceae |

Auricularia sp. (more often cultivated) |

fb |

f |

* |

* |

muer |

木耳 |

muer |

木耳 |

|

|

| Boletaceae |

Boletus spp. |

fb |

f |

** |

* |

niuganjun, dajiaogu |

牛肝菌, 大脚菇 |

niuganjun |

牛肝菌 |

|

204, 236 |

| Cantharellaceae |

Cantharellus cibarius Fr. |

fb |

f |

** |

** |

huangsijun |

牛肝菌 |

huangsijun, jiyoujun |

牛肝菌, 鸡油菌 |

|

203 |

| Gomphaceae |

Ramaria spp. |

fb |

f |

*** |

* |

shuabajun |

刷把菌 |

guoshuajun |

锅刷菌 |

|

205 |

| Hericiaceae |

Hericium sp. |

fb |

f |

* |

* |

houtoujun |

猴头菌 |

houtoujun |

猴头菌 |

|

|

| Marasmiaceae |

Lentinula edodes (Berk.) Pegler (more often cultivated) |

fb |

f |

** |

1 |

yexianggu |

野香菇 |

yexianggu |

野香菇 |

|

|

| Meripilaceae |

Grifola umbellata (Pers.) Pilát |

fb |

f |

** |

** |

zhulingjun |

猪苓菌 |

zhulingjun, zhulinghua |

猪苓菌, 猪苓花 |

|

223 |

| Morchellaceae |

Morchella sp. |

fb |

f |

* |

|

yangquejun |

羊雀菌 |

|

|

|

|

| Pleurotaceae |

Pleurotus sp. |

fb |

f |

*** |

* |

dongjun |

冻菌 |

dongjun |

冻菌 |

|

|

| Polyporaceae |

Laetiporus sulphureus (??) |

fb |

f |

* |

|

jiguanjun |

鸡冠菌 |

|

|

|

|

| Tricholomataceae |

Tricholoma matsutake (S. Ito & S. Imai) Singer (?) |

fb |

f |

|

* |

|

|

songrongjun |

松茸菌 |

|

|

| |

UNIDENTIFIED MUSHROOM |

fb |

f |

* |

|

qiaomianjun |

荞面菌 |

|

|

|

|

| |

UNIDENIFIED TERRESTRIAL GILLED MUSHROOM |

fb |

f |

** |

** |

banlijun |

板栗菌 |

banlijun, maolijun |

板栗菌, 毛栗菌 |

|

|

| |

UNIDENTIFIED MUSHROOM |

fb |

f |

** |

|

qiaomaijun |

荞麦菌 |

|

|

|

|

| |

UNIDENTIFIED MUSHROOM |

fb |

f |

1 |

|

baogujun |

包谷菌 |

|

|

|

|

| |

UNIDENTIFIED MUSHROOM |

fb |

f |

|

* |

|

|

yangdujun |

羊肚菌 |

|

|

| UNIDENTIFIED MUSHROOM | fb | f | * | mabojun | 马脖菌 | ||||||

Ma – Recorded by Ma et al. 2002 [38,39].

Habitat types: e – forest edges, shrubland, forest clearings, grassland; f – forest; r – ruderal; w – water edges; x – ubiquitous.

Parts consumed: fr – fruit, ap –aerial parts, u – underground parts, fl – flowers, b – bark, fb – fruiting body, ls – leaf stalks, if – immature fruits.

Frequency: **** > 50% of respondents; *** > 1/4 of respondents; ** > 1/8 of respondents; * from 2 to 8 respondents; 1 – one respondent.

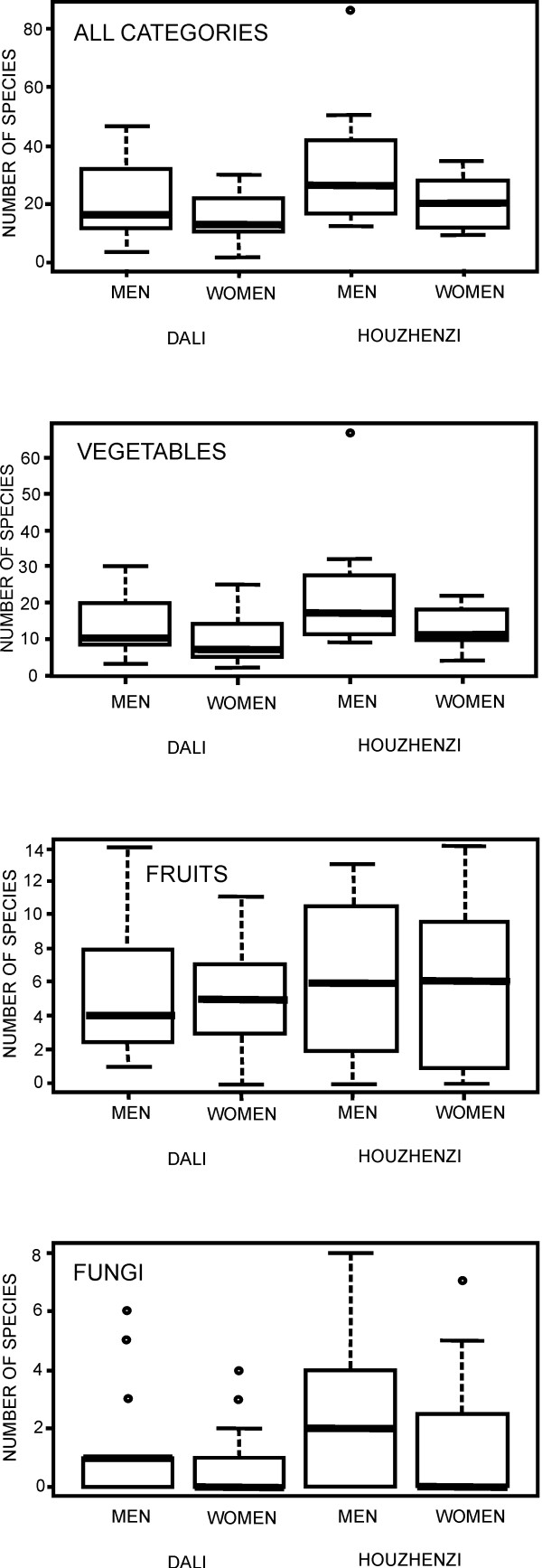

The mean number of freelisted wild foods (Figure 3) was higher in the Houzhenzi valley (24.8 and 17.6 respectively; Mann-Whitney U test, p?<?0.05). A similar trend was observed in all the three categories: wild vegetables (mean 17.5 and 11.5 respectively), fruits (5.9 and 5.1) and fungi (1.9 and 1.0), though the difference was significant only for the vegetables. In both valleys people listed many species of wild vegetables, and few species of fruits, while they struggled to list edible fungi (Figures 3, 4).

Figure 3.

Species numbers freelisted by particular groups: maxima, minima, median (thick line inside a box), 25 and 75 percentile (borders of the box). Outliers are marked with a small circle.

Figure 4.

Use categories in the listed species.

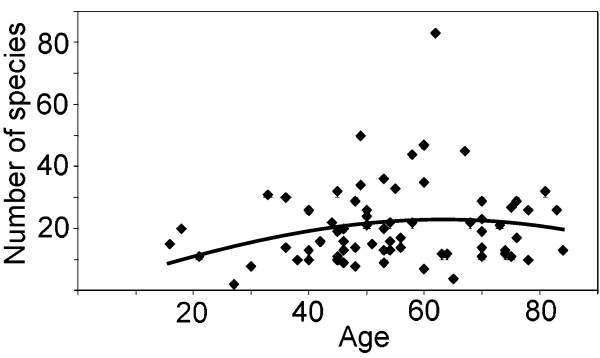

The overall number of species was significantly positively correlated with the male gender (Spearman rho?=?0.29, p?<?0.05) and Houzhenzi valley (rho?=?0.28, p?<?0.05). There was a small correlation with age, but it was not significant. Species number versus age relationship was better explained by a polynominal curve (-0.00665?×2?+?0.8327?×-2.807, R2?=?0.048, p?=?0.18; Figure 5) with maximum values for people in their early sixties, though the fit was still not significant (p?=?0.18).

Figure 5.

The relationship between the listed number of edible species and age. A polynominal curve explains the relationship better than a linear model (-0.00665?×2?+?0.8327?×-2.807, R2?=?0.048, p?=?0.18).

As many as 42% of the folk taxa are typical woodland species and only 21% are ruderal species from fields and field edges. The remaining taxa come from forest edges, forest clearings, thickets, grasslands and water margins, thus in practice over half of the species come from woodland ecosystems. This high proportion of forest species and low proportion of ruderals is even more pronounced in Houzhenzi (44% and 14% respectively, compared to 41% and 25% in Dali, a not significant difference: Chi Squared test, p?=?0.07). Although a large proportion of plants are woodland taxa, it is the herbs that dominate in the species list (69%), with shrubs, trees and vines playing a minor role (15%, 13% and 3% respectively).

Wild vegetables

Wild vegetables are the most important wild food category collected (Figures 3, 4 and 6, 7, 8, Table 3). This was expressed both by the fact that they constituted around two thirds of the species lists and that people most eagerly talked about them. They are also the only category of wild food stored for winter. Drying wild vegetables is a very common preserving technique (Figure 7). Households dry between 1-5 species each year, usually a few kg of dry shoots and leaves, but some households who host tourists can dry even a few times more. Formerly, wild vegetables were lacto-fermented, but now this is done very rarely.

Figure 6.

Matteucia struthiopteris shoots, boiled, strained and sprinkled with oil.

Figure 7.

Drying wild vegetables (Staphylea bumalda) in Houzhenzi in early June 2011.

Figure 8.

Adding wild vegetables to noodle soup is another common form of utilizing the plants.

The number of wild vegetables listed was positively and significantly correlated with place (Houzhenzi versus Dali), male gender and age (Spearman rho equals 0.35, 0.27 and 0.26 respectively), however these are relatively low correlation values.

The ruderal species are collected near homesteads. Their growth is often promoted by sparing them from being sprayed with glyphosate (e.g. Chenopodium album, Hemerocallis spp.). Some forest species are harvested up to 5 km from the villages, up to the altitude of 1800 m a.s.l. At even higher altitudes, wild plants are only harvested while collecting medicinal herbs, which grow even higher.

Wild vegetables are frequently eaten in all meals, mainly as a side dish (cai). The commonest preparation technique is boiling, then straining and sprinkling them with some oil in which Sechuan pepper, garlic, and sometimes ginger, have been fried. This is a side dish, called liang ban, accompanied by home-made wheat bread (bing), rice or other stir-fried foods. Frequently wild vegetables are also put into broad, home-made noodles served in a spicy and sour soup. They are also, rarely, lacto-fermented. Wild vegetables are also sold in all the local restaurants and every agritourist farm has them on their menu.

Fruits

Wild fruits are little appreciated. They are occasionally gathered for fun by children or grown-ups going to the forest. They have never been stored or dried, and are not incorporated in any dishes by anyone, apart from dried Schisandra and Akebia fruits (the latter more rarely), used medicinally. There was no significant correlation between the number of fruits listed and age, location or gender.

Fungi

Few fungi species are used in both valleys. Most people never go to the forest with the purpose of collecting mushrooms, apart from going to collect cultivated Auricularia sp. and Lentinula edodes grown on piles of logs located in the woods. There was no significant correlation between the number of fungi listed and age, location or gender, though the difference between the male and female groups was bordering on significance level (Mann-Whitney U test, p?=?0.08, Spearman rho?=?0.20).

The most frequently mentioned mushrooms in both valleys are Cantherellus cibarius, an unidentified Agaricales (called banlijun, i.e. “chestnut mushroom”), Ramaria spp. treated by locals as one folk taxon and Grifola umbellata, (its sclerotia are additionally collected for medicinal purposes). More than half of the respondents had never collected wild fungi in the forest.

Famine plants

All the older informants were asked about plants eaten during the severe food shortages that plagued China until the last case of famine in 1958-60. However this revealed only a few “famine” plants, as the respondents stated that they rather ate the same wild plants but in larger quantities. Underground organs of plants were particularly eagerly sought after: the rhizomes of Pueraria lobata, Pteridium aquilinum, Polygonatum spp., Sinacalia tangutica, the bulbs of Lilium giganteum and other Lilium species. Nowadays the consumption of underground organs of wild plants has practically ceased. Many respondents also mentioned using the leaves of Abelia engleriana to make a special dish called shenxiandoufu (i.e. fairy tofu). According to legend, during times of famine a fairy/wizard/holy man passed through the area and taught people how to make a special famine tofu with this plant, which saved people from starvation. The bark of Ulmus spp. was used to make famine bread, however not in the 1958-60 famine, but in the previous 1940s famine (before the Liberation), which in this area is remembered as being more severe.

Discussion

It was already pointed out by Kang et al. [13] that the large number of wild greens used in this valley is one of the highest recorded on such a small scale in ethnobotanical studies. Only Zou et al. [9] recorded more, noting the use of 335 taxa of wild vegetables in 10 villages of Hunan, however the latter study was carried out in a larger and more heterogeneous area. Ghorbani et al. [11] recorded the use of 173 wild food plants from 485 informants of four ethnic groups of Naban valley of Xishuangbanna (tropical area of south China), out of which only around a third were wild greens, in contrast to our study where they dominate. However, Ghorbani’s study concerned an area, which was very heterogeneous in terms of elevation, inhabitants and vegetation. The average number of wild food plants listed by one informant was only around 10 species, whereas in this study we documented twice as many taxa per person.

The presented list is also much longer than the lists of wild food plants reported in previous studies from the Qinling Mountains, east from our study area, in the south of the Huxian county [38,39]. Although there was a partial overlap in the species lists (Table 3), the differences show a high geographical diversity of wild vegetable use. Some of these differences may come from differences in habitats, some from cultural choices, and some from the fact that probably only the commonest wild vegetables were reported by Ma et al. [38,39].

It was already pointed out by us in the previous paper [13] that knowledge of wild vegetables in China is additionally encoded in the language (many wild vegetables have cai, i.e. vegetable), in their name. In our study it was 39 taxa (a third of the wild vegetables recorded, mainly the most commonly used ones). Another factor may nowadays help to preserve the knowledge of wild vegetables in China. It is the commodification of wild vegetables by involving them in tourism. Nowadays, nearly every national park in China has local restaurants of wild vegetables (often called “mountain wild vegetables” to emphasize their “naturalness”) (e.g. [9,11,13]). This is part of a broader process of trying to promote or create local attractions in rural China with the hope of drawing the attention of tourists [40]. A similar process occurs in Europe, where wild foods are incorporated in haute cuisine and in revitalized regional dishes [41].

It must be pointed out that the number of wild foods used in many parts of China, in its species-rich parts outside the areas of intense agriculture, is probably an example of an area utilizing the largest number of plant species available to human populations. This huge list of plants is mainly made up by wild greens. This attitude was named by Łuczaj [42] as herbophilia, and here in China it takes its most extreme form. The number of wild food plants used in the studied valley comparable to the lists of edible plants recorded on a country scale in Europe (e.g. [43-49]). The utilization of such a large number of greens may also be found in some communities in other countries of Eastern Asia, e.g. Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Thailand [50-57], as well as in some parts of India and Africa [54,57]. The number of wild food plants used by the studied communities in the Qinling Mountains is similar to that used by the few communities in the world previously reported as using the highest numbers of wild food plants species (between 171 and 252), i.e. Igbo ib southern Nigeria, Dalit in Andhra Pradesh or Karen in NW Thailand ([57] after [54]).

In many tropical and subtropical areas the choice of species is limited by the fact that primary tropical vegetation has thick leathery leaves and mainly ruderal plants are eaten. In the mountains of China the choice of edible species is increased by two factors:

1. large elevation differences enabling easy access to different vegetation zones;

2. deciduous vegetation with many forest understory perennials with delicate leaves and buds.

In our study around half of the wild vegetables come from the forest. This is in contrast with other ethnobotanical studies showing that human populations, even in wooded areas, tend to over-utilize the ruderal flora [14,58-60]. On the other hand the results of this study are very similar to the data on the use of wild food plants by the Karen ethnic group in the forests of NW Thailand, for whom wild forest vegetables also constitute a major part of the wild plants consumed [55]. Interestingly, the large diversity of wild vegetables (also those which are typical woodland species) used in Eastern Asia remains in stark contrast with the extremely low number of wild vegetables used in the Amazon in similar environments [61].

What is interesting is the large domination of wild greens over fruits and fungi. The list of mushrooms is for example shorter than the number of mushroom species used locally in Poland [62] or Mexico [63]. The lack of interest in wild edible mushrooms in the studied area is puzzling, as China is sometimes regarded as a mycophilous part of the world [64,65]. It may arise from the easy access to the cultivated Auricularia and Lentinula mushrooms and extremely steep terrain, making foraging for fungi difficult. In Yunnan, famous for edible fungi, the hills and mountains are often less steep (ŁŁ, personal observations). Collecting mushrooms requires more walking to find them than in the case of wild vegetables whose location is more permanent. Our results encourage further research into the knowledge and use of edible fungi in rural areas in China.

Do men know more?

In the Qinling mountains the collection of wild food plants is the domain of both sexes. On the other hand it must be noted that men slightly outperform women in listing slightly more species of wild vegetables, and many more species of fungi (Table 3). These results may be caused by the fact that a larger proportion of men get involved, regularly or occasionally, in collecting medicinal plants for sale. As they make long trips into higher elevations they acquire a vast knowledge of local woodland flora. This may explain the larger number of species listed, even though it may be the women who spend more hours collecting wild plants. This slight domination of men in this domain is quite unusual, as in many countries it is the women who are the main holders of knowledge on wild vegetables (e.g. [42,66,67]), and even fungi [68]. This unusual tendency was also noted in Poland, where it is the men who are more involved in collecting wild fungi [62].

Conclusions

The study yielded one of the longest lists of wild food plants used locally ever recorded in ethnobotanical studies. In both the studied valleys, wild vegetables are still widely used throughout the year and preserved for winter. In the more developed Dali valley people use slightly fewer wild vegetables than in the Houzhenzi area. Although usually only a few species are collected in larger quantities, knowledge about these plants is still very alive. On the other hand the community shows relative indifference to wild fruits and fungi, which are rarely collected, and only as an additional activity. There were small differences in the knowledge of wild foods among the members of different age groups and between men and women.

The results of this study show that further in-depth ethnobotanical research is needed to determine patterns in wild food plant and fungi use in different parts of China, as locally these patterns may be extremely variable. Also more research recording age and gender differences is needed.

Competing interests

The authors state that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All the authors took part in the interviewing process in the field, voucher specimen preparation and data processing, and read the final version of the manuscript. ŁŁ designed the study, YK organized the expedition, led the interviews and identified most taxa. ŁŁ and YK wrote the article together. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yongxiang Kang, Email: kangchenj@yahoo.com.cn.

Łukasz Łuczaj, Email: lukasz.luczaj@interia.pl.

Jin Kang, Email: 250367563@qq.com.

Shijiao Zhang, Email: 675261368@qq.com.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the inhabitants of the studied villages for their willingness in sharing information on the use of the species. We are also grateful for advice on statistical matters to Dr Tomasz Wyszomirski (Institute of Botany, University of Warsaw). The program was financially supported by the Forestry Research Foundation for the Public Service Industry of China (2009,04004) and by the University of Rzeszów (Institute of Biotechnology and Basic Sciences, as well as a special grant from the rector of the university).

References

- Wang X, Du X. Recent status of the development and strategies of exploitation of non-wood forest products in China. Forest Res (China) 1997;10(2):199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Huai H-Y, Pei S-J. Khasbagan. Wild plants in the diet of Arhorchin Mongol herdsmen in Inner Mongolia. Econ Bot. 2000;54(4):528–536. doi: 10.1007/BF02866550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long C-L, Li H, Ouyang Z, Yang X, Li Q, Trangmar B. Strategies for agrobiodiversity conservation and promotion: a case from Yunnan, China. Biodiversity Conserv. 2003;12(6):1145–1156. doi: 10.1023/A:1023085922265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. “Turning waste into things of value”: marketing fern, kudzu, and osmunda in enshi prefecture. J Dev Soc. 2003;19(4):433–457. doi: 10.1177/0169796X0301900401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Tao G, Liu H, Yan K, Dao X. Wild vegetable resources and market survey in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Econ Bot. 2004;58(4):647–667. doi: 10.1663/0013-0001(2004)058[0647:WVRAMS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XP, Wu JL, Li Y, Liu F, Wang JQ. Investigation on species resources and utilization of wild vegetable in Nabanhe watershed nature reserve, Xishuangbanna. J South Forestry Coll. 2004;24:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Weckerle CS, Huber FK, Yongping Y, Weibang S. Plant knowledge of the Shuhi in the Hengduan mountains, southwest China. Econ Bot. 2006;60(1):3–23. doi: 10.1663/0013-0001(2006)60[3:PKOTSI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wujisguleng W, Khasbagen K. An integrated assessment of wild vegetable resources in Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region, China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2010;6:34. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X, Huang F, Hao L, Zhao J, Mao H, Zhang J, Ren S. The socio-economic importance of wild vegetable resources and their conservation: a case study from China. Kew Bulletin. 2010;65:577–582. doi: 10.1007/s12225-010-9239-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huber FK, Ineichen R, Yang K, Weckerle CS. Livelihood and conservation aspects of Non-wood forest product collection in the Shaxi Valley, Southwest China. Econ Bot. 2010;64(3):189–204. doi: 10.1007/s12231-010-9126-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani A, Langenberger G, Sauerborn J. A comparison of the wild food plant use knowledge of ethnic minorities in naban river watershed national nature reserve, Yunnan, SW China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2012;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani A, Langenberger G, Liu J-X, Wehner S, Sauerborn J. Diversity of medicinal and food plants as non-timber forest products in Naban River Watershed National Nature Reserve (China): implications for livelihood improvement and biodiversity conservation. Econ Bot. 2012;66:178–191. doi: 10.1007/s12231-012-9188-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Łuczaj Ł, Ye S, Zhang S, Kang J. Wild food plants and wild edible fungi of Heihe valley (Qinling Mountains, Shaanxi, central China): herbophilia and indifference to fruits and mushrooms. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2012;81(4):405–413. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner NJ, Łuczaj ŁJ, Migliorini P, Pieroni A, Dreon AL, Sacchetti LE, Paoletti MG. Edible and tended wild plants, traditional ecological knowledge and agroecology. Cr Rev Plant Sci. 2011;30(1–2):198–225. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EN. New Haven and London: Yale University Press; 1988. (The food of China). [Google Scholar]

- Hu SY. Food Plants of China. Hongkong: The Chinese University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Łuczaj Ł, Ye S. The highly toxic Aconitum carmichaelii Debeaux as a root vegetable in the Qinling Mountains (Shaanxi, China) Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2012;59:1569–1575. doi: 10.1007/s10722-012-9853-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X, Yang G, Zhu F, Qin X, Wang D, Liu Z, Feng Y. Plant communities, species richness and life-forms along elevational gradients in Taibai Mountain, China. African J Agricul Res. 2012;7(12):1834–1848. doi: 10.5897/AJAR11.1322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ying T-S, Li Y-F, Guo Q-F, Cui H. Observations on the flora and vegetation of Taibai Shan, Qinling mountain range, Southern Shaanxi, China. Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica. 1990;28(4):261–293. [Google Scholar]

- Economic survey of the Zhouzhi county economic survey of the Zhouzhi county Houzhenzi town, protected areas. (in Chinese) http://wwf.nwsuaf.edu.cn/article/2007/0912/news_219.html.

- Houzhenzi town. http://www.subject-knowledge.us/Wikipedia-963035-Houzhenzi-town.html.

- Wang ZY, Hu RY, Deng XS, Fan XF. The test of dropping irrigation techniques for apple orchards at the foot of the North slope of the Qinling Mt. 陕西农业科学 Shaanxi Agricul Sci. 1985;2:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Meixian county. (in Chinese). http://baike.911cha.com/MTBwMTg = .html.

- Committee of chorography of Foping county: 1993. 佛坪县志 Foping county annals. Xi’an: San Qing press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Committee of chorography of Zhouzhi county, 1993. 周至县志 Zhouzhi county annals. Xi’an: San Qing press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Committee of chorography of Meixian county. 眉县志 Meixian county annals. Xi’ab: Shaanxi People’s Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Neurauter J, Liu X, Liao C. The role of traditional ecological knowledge in protected area management: a case study of Guanyinshan Nature Reserve, Shaanxi, China. Sustaining Gondwana. 2009;19(2):1–74. [Google Scholar]

- American Anthropological Association Code of Ethics. http://www.aaanet.org/issues/policy-advocacy/upload/AAA-Ethics-Code-2009.pdf.

- International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics (with 2008 additions) http://ethnobiology.net/code-of-ethics/

- Alexiades NM. In: Scientific Publications Department. Alexiades NM, editor. New York: The New York Botanical Garden; 1996. Selected Guidelines for Ethnobotanical Research: A Field Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Martin GJ. Ethnobotany: A methods manual. London. Earth scans; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AB. Applied Ethnobotany; people, wild plant use and conservation: London and Sterling. London: Earthscan Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EN, Pearsall D, Hunn E, Turner N, editor. Ethnobiology. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sutrop U. List task and a cognitive salience index. Field Methods. 2001;3(13):263–276. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan M. Considerations for collecting freelists in the field: examples from ethnobotany. Field Methods. 2005;17(3):219–234. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05277460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer O, Harper DAT, Ryan PD. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Paleontologia Electronica. 2001;4(1):9. [Google Scholar]

- PAST version 2.17b. http://folk.uio.no/ohammer/past, accessed 15 Nov 2012.

- Ma X, Zhang J, Lu S, Cui Z, Zhao H, Zheng J. 秦岭北坡主要山野菜分布规律调查 The survey of the distribution of wild vegetables in the northern slope of the Qinling Mountains. 中国林副特产 Quaterly Forest By-product Speciality China. 2002;61(2):50. [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Hu P, Zhang Y, Wu J, Zhang J, Cui Z. 秦岭北坡山野菜生境及开发利用 the habitat, development and utilization of wild vegetables in the northern slope of the qinling mountains. 特种经济动植物 Special Economic Animal. 2002;2:37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt EA. China: Master’s Thesis, Applied Anthropology, Oregon State University; 2011. (Commodification in an Ersu Tibetan village of Sichuan). http://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1957/21802/SchmittEdwinA2011.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj Ł, Pieroni A, Tardío J, Pardo-de-Santayana M, Sõukand R, Svanberg I, Kalle R. Wild food plant use in 21st century Europe: the disappearance of old traditions and the search for new cuisines involving wild edibles. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2012;81(4):359–370. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj Ł. Archival data on wild food plants used in Poland in 1948. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2008;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardío J, Pardo De Santayana M, Morales R. Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants in Spain. Bot J Linnean Soc. 2006;152:27–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2006.00549.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Redžić S. Wild edible plants and their traditional use in the human nutrition in Bosnia‐Herzegovina. Ecol Food Nutr. 2006;45(3):189–232. doi: 10.1080/03670240600648963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj ŁJ, Kujawska M. Botanists and their childhood memories: an under-utilized expert source in ethnobotanical research. Bot J Linn Soc. 2012;168:334–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2011.01205.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj Ł. Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants of Slovakia. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2012;81(4):245–255. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalle R, Sõukand R. Historical ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants of Estonia (1770s–1960s) Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2012;81(4):271–281. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svanberg I. The use of wild plants as food in pre-industrial Sweden. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2012;81(4):317–327. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dénes A, Papp N, Babai D, Czúcz B, Molnár Z. Wild plants used for food by Hungarian ethnic groups living in the Carpathian Basin. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2012;81(4):381–396. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton RW, Lee NS. Wild food plants in South Korea; market presence, new crops, and exports to the United States. Econ Bot. 1996;50:57–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02862113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T. Cyclopaedia of edible plants of the world. Tokyo: Keigaku Publishing; 1976. OpenURL. [Google Scholar]

- Ogle BM, Hung PH, Tuyet HT. Significance of wild vegetables in micronutrient intakes of women in Vietnam: an analysis of food variety. Asia Pacific J Clin Nutri. 2001;10(1):21–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-6047.2001.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Garcia GS, Price LL. Weeds as important vegetables for farmers. Acta Soc Bot. 2012;81(4):397–403. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]