Abstract

PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to examine the validity of seven child-specific ActiGraph prediction equations/cut-points (Crouter vector magnitude 2-regression model (Cvm2RM), Crouter vertical axis 2RM (Cva2RM), Freedson, Treuth, Trost, Puyau and Evenson) for estimating energy expenditure (EE) and time spent in sedentary behaviors, light physical activity (LPA), moderate PA (MPA), and vigorous PA (VPA).

METHODS

Forty boys and 32 girls (mean±SD; age, 12±0.8 yrs) participated in the study. Participants performed eight structured activities and approximately 2-hrs of free-living activity. Activity data was collected using an ActiGraph GT3X+, positioned on the right hip, and EE (METRMR; activity VO2 divided by resting VO2) was measured using a Cosmed K4b2. ActiGraph prediction equations were compared against the Cosmed for METRMR and time spent in sedentary behaviors, LPA, MPA, VPA, and MVPA.

RESULTS

For the structured activities, all prediction methods were significantly different from measured METRMR for ≥ 3 activities (P<0.05), however all provided close estimates of METRMR during walking. On average, participants were monitored for 95.0±36.5 minutes during the free-living measurement. The Cvm2RM and Puyau methods were within 0.9 METRMR of measured free-living METRMR (P>0.05); all other methods significantly underestimated measured METRMR (P<0.05). The Cva2RM was within 9.7 minutes of measured time spent in sedentary behaviors, LPA, MPA, and MVPA, which was the best of the methods examined. All prediction equations underestimated VPA by 6.0–13.6 minutes.

CONCLUSION

Compared to the Cosmed, the Cvm2RM and Puyau methods provided the best estimate of METRMR and the Cva2RM provided the closest estimate of time spent in each intensity category during the free-living measurement. Lastly, all prediction methods had large individual prediction errors.

Keywords: Motion sensor, oxygen consumption, activity counts variability, free-living activity, structured activity

INTRODUCTION

Self-report measures have traditionally been used for measurement of free-living physical activity (PA); however self-report measures have inherent limitations such as participant recall of activities and the ability of an individual to accurately classify the intensity of the activities which they perform. In addition, the limitations of self-report are believed to be even greater in children. Objective measures such as accelerometers have been shown to provide more accurate estimates of PA and have become the method of choice by researchers for measuring PA in children (23, 24). Accelerometers have the ability to track PA intensity, duration, and frequency as well as provide estimates of energy expenditure (EE) and time spent in sedentary behaviors (< 1.5 METs), light PA (LPA; 1.5 – 2.99 METs), moderate PA (MPA; 3 –5.99 METs), vigorous PA (VPA ≥ 6 METs), and moderate and vigorous PA (MVPA ≥ 3 METs) with minimal subject burden.

Traditionally, researchers predicted EE and time spent in activity categories using single regression equations relating the accelerometer counts to measured EE (11, 15, 17, 18, 22, 26). In general, no single regression equation developed for use in children provides accurate predictions across a wide range of activities (6, 8, 25). Recently, alternative approaches have been used in children such as Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) (10, 13, 25), while in adults pattern recognition (e.g. hidden Markov models (16) and artificial neural networks (12, 21)) have been used.

Traditionally, most accelerometers have used only a single vertical axis due to constraints imposed by battery life and memory storage. With technological advances triaxial accelerometers are now more common and are able to record the raw acceleration data for three axes, over several weeks. In addition, there is some evidence to suggest that the use of a triaxial accelerometer provides more accurate estimates of EE and time spent in intensity categories versus using a single axis accelerometer (2, 9, 19, 29). Recently, we developed two different 2-regression models (2RM) for use in children (6), which are based on our previous work in adults (4, 7). One uses only the vertical axis (Cva2RM) and one that uses the vector magnitude (Cvm2RM). In addition, we have previously shown that the Cva2RM and Cvm2RM significantly improve estimates of EE and time spent in LPA, MPA, and VPA, compared to the more widely used child-specific single regression equations (6).

A limitation to our previous work is that we used a hold out sample to cross-validate the child-specific 2RMs using the same activities on which they were developed. This cross-validation method has potential to bias the results to make the 2RMs look more accurate than they truly are. In addition, while there are a few free-living studies in children using doubly labeled water (DLW), the majority of validation studies have used structured activities. While DLW is considered the gold standard for measuring EE in a free-living environment it does not provide information on bout duration or intensity of activities performed. Thus, there is a need for free-living studies that use indirect calorimetry to estimate EE and time spent in PA intensity categories. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the validity of the Cvm2RM and Cva2RM (6), and the child-specific single regression equations/cut-points of Freedson et al. (11), Trost et al. (26), Treuth et al. (22), Puyau et al. (17), and Evenson et al (10) for estimating EE and time spent in sedentary behaviors, LPA, MPA, VPA, and MVPA during eight structured activities and approximately two hours of free-living activity.

METHODS

Participants

Thirty-two girls and 40 boys between the ages of 11 and 15 yrs volunteered to participate in the study. The procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Massachusetts Boston and Boston Public School Institutional Review Boards before the start of the study. The parent of each participant signed a written informed consent and filled out a health history questionnaire and each participant signed a written assent prior to participation in the study. Children were excluded from the study if they had any contraindications to exercise, or were physically unable to complete the activities. In addition, none of the children were taking any medications that would affect their metabolism (e.g. Concerta or Ritalin).

Procedures

Testing was performed over a three day period. On day 1, anthropometric measurements were taken and children performed 30 minutes of rest, lying on a table in a quiet room for an estimate of resting metabolic rate (RMR). On day 2, participants performed seven structured activities. On day 3, participants performed approximately two hours of free-living activity. All participants performed the resting measurement, however due to scheduling issues, not all participants completed all activity testing on days two and three (see table 1 for number of participants per activity). The testing took place at GoKids Boston, located on the campus of the University of Massachusetts Boston or at a local Boston Public School. The physical characteristics of the children are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the participants.

| Males (n=40) | Females (n=32) | All Participants (n=72) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) ± SD (range) | 12.8 ± 0.9 (11–15) | 12.6 ± 0.7 (11–14) | 12.7 ± 0.8 (11–15) |

| Height (cm) ± SD (range) | 159.9 ± 10.9 (139–188) | 154.5 ± 8.7 (128–168) | 157.5 ± 10.3 (128–188) |

| Weight (kg) ± SD (range) | 59.1 ± 16.3 (32–98) | 54.6 ± 17.4 (32–103) | 57.1 ± 16.9 (32–103) |

| Resting VO2 (ml·kg−1·min−1) | 5.3 ± 1.6 (2.8–8.7) | 4.7 ± 1.6 (2.4–8.8) | 5.0 ± 1.6 (2.4–8.8) |

| BMI Classification | |||

| Normal Weight (5th–85th percentile) | 47.5% | 54.8% | 50.7% |

| Overweight (85th–95th percentile) | 25.0% | 19.4% | 22.5% |

| Obese (≥ 95th percentile) | 27.5% | 25.8% | 26.8% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 32.5% | 34.4% | 33.4% |

| Black/African American | 65.0% | 62.5% | 63.9% |

| Asian | 12.5% | 12.5% | 12.5% |

| White | 22.5% | 25.0% | 23.6% |

| Number completing each Activity | |||

| Supine Rest (n) | 40 | 32 | 72 |

| Playing on a desktop computer (n) | 25 | 18 | 43 |

| Playing board games/cards (n) | 25 | 18 | 43 |

| Light cleaning (n) | 25 | 18 | 43 |

| Jackie Chan (n) | 25 | 18 | 43 |

| Wall Ball (n) | 25 | 18 | 43 |

| Walking (n) | 32 | 29 | 61 |

| Running (n) | 31 | 28 | 59 |

| Free-Living (n) | 27 | 15 | 42 |

Structured Activity Measurement

For the structured activities (day 2), children performed each activity for eight minutes with a 3-minute break between each activity. Activities were performed in the following order: 1) Using a desktop computer to search the internet or play games, 2) Playing board games/cards, 3) light cleaning (e.g. sweeping, dusting, wiping down equipment), 4) Jackie Chan (an interactive video game where the participant runs in place on a mat which moves a character on a TV screen), 5) Wall Ball (variation on handball), 6) Walking a designated route involving stairs, crossing roads, and variable terrain at a self-selected pace, and 7) Running a designated route (the same one used for the walking bout) at a self-selected pace. Oxygen consumption (VO2) was measured continuously during the RMR test and each activity using indirect calorimetry (Cosmed K4b2, Rome Italy). Simultaneously, data were collected using an ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometer positioned on the right hip. This study was part of a larger study and in addition to the ActiGraph worn on the hip; the children wore several other activity monitors. However, only the ActiGraph data from the hip are presented here. To account for the additional weight of the Cosmed K4b2, ActiGraph, and additional devices, 2 kg was added to the child’s body weight.

Free-Living Measurement

For the free-living measurement (day 3) children were fitted with a Cosmed K4b2 and accelerometers as described previously. Participants were monitored for approximately two hours during the free-living measurement. During this time a research assistant followed the child to observe their activity, but did not communicate with the child or tell them what activities they should perform. If needed, the participant was allowed to take water breaks. The children were allowed to move around the University or School campus, but could not leave the property during testing. The types of activities performed during the free-living measurement period included; sedentary behaviors (e.g., watching movies, reading, playing computer games, homework), active games (e.g., Dance Dance Revolution, Nintendo Wii, Light Space, Jackie Chan), and recreational activities (soccer, walking around the property, basketball, lifting weights, catch with a ball).

Anthropometric measurements

Prior to testing, children had their height and weight measured (in light clothing, without shoes) using a stadiometer and a physician’s scale, respectively. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated according to the formula: body mass (kg) divided by height squared (m2) and gender and age specific BMI percentiles were calculated using CDC algorithms (3).

Indirect calorimetry

The children wore a Cosmed K4b2 during all of the activity testing. Prior to each test the oxygen and carbon dioxide analyzers were calibrated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This consisted of performing a room air calibration, and a reference gas calibration using 15.93% oxygen and 4.92% carbon dioxide. The flow turbine was then calibrated using a 3.00 L syringe (Hans-Rudolph). Finally, a delay calibration was performed to adjust for the lag time that occurs between the expiratory flow measurement and the gas analyzers.

ActiGraph accelerometer

The ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometer is a small (4.6 × 3.3 × 1.5 cm), lightweight (19 grams), water resistant tri-axial accelerometer. The GT3X+ measures accelerations ranging in magnitude from ± 6 G’s. Unlike previous ActiGraph models, the GT3X+ stores the raw acceleration data at a user-specified sampling rate between 30 and 100 Hz. Once the raw data are downloaded, the ActiLife software can be used to convert the raw data to a user specified epoch (e.g. 10 sec), which is comparable to previous ActiGraph models. During all testing the GT3X+ was worn on the waist at the right anterior axillary line attached to a nylon belt. The GT3X+ was set to collect data at 30 Hz, and the low frequency extension turned on. The GT3X+ time was synchronized with a digital clock so that the start time could be synchronized with the Cosmed K4b2.

Data analysis

Breath-by-breath data were collected by the Cosmed K4b2, which was averaged over a one minute period. For each structured activity and the free-living measurement, the VO2 (ml·min−1) was converted to VO2 (ml·kg−1·min−1). In adults, 3.5 ml·kg−1·min−1 is used to define 1 MET, however children and adolescents have higher resting metabolic rates than adults and if the standard definition of 3.5 ml·kg−1·min−1 is used it would result in an overestimation of the measured energy cost (i.e. MET value) of an activity (14, 20). Thus, METs were calculated by dividing the VO2 (ml·kg−1·min−1) for each activity by the child’ssupine resting VO2 (ml·kg−1·min−1). Hereafter, the use of METRMR will refer to measured activity VO2 divided by measured supine resting VO2 and MET3.5 will refer to the standard definition used for adults of 1 MET=3.5 ml·kg−1·min−1. For each structured activity, the METRMR values for minutes 4 to 7 were averaged and used for the subsequent analysis. All minutes of the free-living measurement were used; except when the mask was removed for water breaks.

The ActiGraph accelerometer data for each axis were collected at 30 Hz and converted to counts per 10 seconds and counts per minute. Mean vector magnitude per 10 seconds and per minute were calculated as the square root of the sum of the squared activity counts for each axis. For each structured activity an average METRMR value was calculated using the Cva2RM, Cvm2RM, and the child-specific single regression equations developed by Freedson et al. (11), Trost et al. (26), Treuth et al. (22), and Puyau et al. (17). For the free-living activity, METRMR and time spent in sedentary behaviors (< 1.50 METRMR), LPA (1.50–2.99 METRMR), MPA (3.00–5.99 METRMR), VPA (≥ 6.00 METRMR), and MVPA (≥ 3.00 METRMR) were calculated using the same regression models as used for the structured activities. In addition, for the free-living activity measurement, PA intensity categories were also estimated using the Evenson cut-points (10). In children and adolescents there has been debate whether to use 3 or 4 METs to define MPA. While some studies have used 4 METs to define MPA (10, 25) others have used 3 METs (11, 17). The choice to use 3 METs in the current study is based on the current PA guidelines for children and adolescents also using 3 METs to define MPA (28). So that sedentary behavior could be compared between models, we chose to define sedentary behavior for the single regression models (Freedson, Treuth, Trost, and Puyau equations), as <100 counts·min−1, which is a commonly used sedentary cut-point (23). It should be noted that for this study sedentary behaviors are defined as any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure < 1.5 METs, which includes activities such as sitting and reclining. The Puyau equation was developed with a sedentary cut-point of <800 counts·min−1, however for the current analysis 100 counts·min−1 was used with this equation due to previous research showing that the use of this cut-point works well for estimating sedentary time, but significantly decreases the estimate LPA (25). Thus, 100 counts·min−1 was used with the Puyau equation to evaluate if the estimate of LPA would be improved without affecting the accuracy of predicted sedentary time. For the Cva2RM a sedentary cut-point of ≤25 vertical axis countsper 10 seconds was used and for the Cvm2RM the sedentary cut-point was ≤ 75 vector magnitude counts per 10 seconds (6). Since we chose to express our measured EE value as METRMR, we felt it was necessary to convert all prediction equations to a comparable METRMR value to ensure a fair evaluation of the prediction equations. For the Freedson and Treuth equations, which both predict MET3.5, we multiplied the predicted MET3.5 value for each activity, by 3.5 ml·kg−1·min−1 to obtain a predicted VO2 value, which was then divided by the measured supine resting VO2 to get a predicted METRMR. The Trost and Puyau equations predict kcal·min−1 and kcal·kg−1·min−1, respectively, thus they were also converted to METRMR values using the measured resting values.

Statistical treatment

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 17.0 for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). For all analyses, an alpha level of 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. All values are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), unless noted otherwise.

One-way repeated measures ANOVAs were used to compare measured (Cosmed) and predicted METRMR for: 1) each structured activity; and 2) the free-living activity. One-way repeated measures ANOVAs were also used to compare measured and predicted time spent in sedentary behaviors, LPA, MPA, VPA, and MVPA during the free-living activity. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustments were performed to locate significant differences, when necessary.

Measured and predicted METRMR were used to calculate a root mean squared error (RMSE; square root of the mean of the squared differences between the prediction and the criterion measure) for each structured activity and the free-living measurement. The use of RMSE allows one to examine the precision of a prediction equation, with a lower RMSE indicating a more precise estimate.

RESULTS

Validation During Structured Activities

Table 2 shows the measured and predicted METRMR and RMSE values for supine rest and the seven structured activities. Based on the mean values, the Cvm2RM and Puyau provided the closest estimates of METRMR and were within 1.1 (1.0–23.1%) METRMR and 1.3 (6.5–26.6%) METRMR, respectively, of the measured METRMR for each of the activities. However, they were each significantly different for three of the eight activities. The other prediction models were significantly different from measured METRMR for 4–6 activities and had errors ranging from 0.1–2.2 METRMR (1.0–44.5%). In general, the estimated METRMR values were lower than the measured METRMR values for all activities except for supine rest. The Trost equation was significantly different from measured METRMR for five activities; however it had the lowest average RMSE across all activities (1.23 METRMR). The RMSE values for the other prediction models ranged from 1.32 METRMR (Cvm2RM) to 1.60 (Puyau equation).

Table 2.

Measured (Cosmed K4b2) and predicted METRMR (mean (± SD)) and root mean squared error (RMSE) for eight structured activities.

| Cosmed K4b2 | Crouter Vector Magnitude 2-Regression Model | Crouter Vertical Axis 2-Regression Model | Freedson Child Equation | Treuth Equation | Trost Equation | Puyau Equation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | RMSE | Mean (SD) | RMSE | Mean (SD) | RMSE | Mean (SD) | RMSE | Mean (SD) | RMSE | Mean (SD) | RMSE | |

| Supine rest (n=72) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.01 (0.07) | 0.07 | 1.03 (0.24) | 0.24 | 1.01 (0.67) | 0.07 | 1.02 (0.12) | 0.12 | 1.04 (0.21) | 0.21 | 1.07 (0.34) | 0.34 |

| Playing on a desktop computer (n=43) | 1.34 (0.48) | 1.03 (0.13)* | 0.53 | 1.00 (0.00)* | 0.59 | 1.01 (0.05)* | 0.56 | 1.01 (0.08)* | 0.55 | 1.00 (0.03)* | 0.57 | 1.04 (0.25)* | 0.50 |

| Playing board games/cards (n=43) | 1.42 (0.50) | 1.11 (0.24)* | 0.59 | 1.09 (0.42)* | 0.65 | 1.07 (0.26)* | 0.59 | 1.10 (0.37)* | 0.60 | 1.14 (0.56) | 0.68 | 1.13 (0.42) | 0.65 |

| Light cleaning (n=43) | 2.93 (1.25) | 2.65 (0.48) | 1.22 | 2.84 (0.70) | 1.25 | 1.66 (0.65)* | 1.58 | 1.88 (0.70)* | 1.37 | 2.15 (0.99)* | 1.32 | 2.71 (0.61) | 1.59 |

| Jackie Chan (n=43) | 4.69 (1.41) | 3.99 (0.95) | 1.72 | 3.97 (0.83) | 1.68 | 3.11 (1.35)* | 2.00 | 3.12 (1.23)* | 1.92 | 3.48 (1.40)* | 1.71 | 3.98 (1.20) | 2.02 |

| Wall Ball (n=43) | 4.96 (2.29) | 4.13 (0.79) | 2.21 | 3.70 (0.44)* | 2.50 | 2.75 (1.10)* | 2.70 | 2.81 (1.03)* | 2.65 | 3.17 (1.20)* | 2.36 | 3.64 (0.81)* | 2.77 |

| Walking (n=61; avg. 71.7 m·min−1) | 4.12 (1.52) | 3.81 (0.64) | 1.59 | 3.52 (0.52) | 1.60 | 3.85 (1.47) | 1.16 | 3.74 (1.41) | 1.15 | 4.06 (1.51) | 1.12 | 4.39 (0.62) | 1.79 |

| Running (n=59; avg. 113.1 m·min−1) | 6.67 (2.52) | 5.54 (0.96)* | 2.64 | 5.55 (1.48)* | 2.64 | 5.73 (2.30)* | 1.96 | 5.30 (2.08)* | 2.18 | 5.76 (2.21)* | 1.90 | 6.00 (1.12)* | 3.14 |

| Average for all activities | 3.38 (2.47) | 2.91 (1.77)* | 1.32 | 2.84 (1.76)* | 1.39 | 2.59 (2.03)* | 1.33 | 2.55 (1.87)* | 1.4 | 2.77 (2.07)* | 1.23 | 3.03 (1.92)* | 1.60 |

METRMR, metabolic equivalents (measured VO2 divided by measured lying RMR VO2);

Significantly different from Cosmed K4b2 (P < 0.05),

Validation During Free-Living

On average, children were monitored for 95.0±36.5 minutes during the free-living measurement period. Table 3 shows the average METRMR, mean bias and RMSE from the free-living measurement. The Cvm2RM and Puyau equations were the only prediction models not significantly different from the measured METRMR, however they still underestimated measured METRMR by 26.3% and 16.7%, respectively. The other equations significantly underestimated by 27.2% (Crouter 2VA2RM) to 37.9% (Freedson equation). The Puyau equation, which had the lowest mean bias (0.6) had the second highest RMSE (1.64). The Cvm2RM and Cva2RM had the lowest RMSE (1.50 and 1.55 respectively).

Table 3.

Measured (Cosmed K4b2) and predicted METRMR, root mean squared error (RMSE), mean bias (measured minus predicted) and 95% prediction intervals (95%PI) for the free-living measurement.

| Cosmed K4b2 | Crouter Vector Magnitude 2-Regression Model | Crouter Vertical Axis 2-Regression Model | Freedson Child Equation | Treuth Equation | Trost Equation | Puyau Equation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (±SD) METRMR | 3.35 (2.11) | 2.47 (0.95) | 2.44 (0.92)* | 2.08 (1.51)* | 2.11 (1.09)* | 2.30 (1.23)* | 2.79 (1.09) |

| Mean bias (95% PI) | --- | 0.89 (−1.99, 3.77) | 0.91 (−1.97, 3.79) | 1.27 (−0.95, 3.49) | 1.24 (−1.04, 3.52) | 1.05 (−1.17, 3.27) | 0.56 (−2.62, 3.74) |

| RMSE | --- | 1.50 | 1.55 | 1.65 | 1.63 | 1.56 | 1.64 |

METRMR, metabolic equivalents (measured VO2 divided by measured lying RMR VO2);

Significantly different from Cosmed K4b2 (P < 0.05),

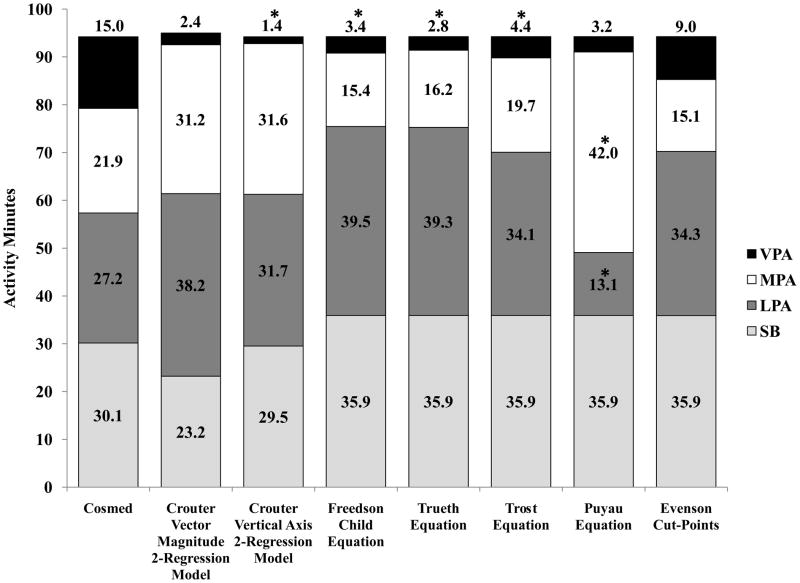

Mean measured and predicted time spent in sedentary behaviors, LPA, MPA, VPA, and MVPA during the free-living measurement are shown in figure 1. Table 4 shows the mean bias and 95% prediction intervals (95% PI).

Figure 1.

Distribution of average time spent in sedentary behaviors (SB), light physical activity (LPA), moderate physical activity (MPA) and vigorous physical activity (VPA) during the free-living measurement period for the Cosmed K4b2 and each prediction equation. *significantly different from Cosmed time (P<0.05).

Table 4.

Mean bias (measured minus predicted) and lower and upper 95% prediction intervals for time spent in sedentary behaviors, light physical activity (LPA), moderate physical activity (MPA), vigorous physical activity (VPA) and moderate and vigorous physical activity (MVPA) during the free-living measurement.

| Crouter Vector Magnitude 2-Regression Model | Crouter Vertical Axis 2-Regression Model | Freedson Child Equation | Treuth Equation | Trost Equation | Puyau Equation | Evenson Cut-Points | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary Behaviors | 6.9 (−36.3, 50.2) | 0.6 (−40.3, 41.6) | −5.8 (−47.2, 35.6) | −5.8 (−47.2, 35.6) | −5.8 (−47.2, 35.6) | −5.8 (−47.2, 35.6) | −5.8 (−47.2, 35.6) |

| LPA | −11.0 (−47.8, 25.9) | −4.5 (−39.4, 30.4) | −12.3 (−71.7, 47.0) | −12.1 (−71.8, 47.6) | −6.9 (−64.5, 50.7) | 14.1 (−29.8, 58.0) | −7.0 (−48.8, 34.8) |

| MPA | −9.3 (−55.7, 37.1) | −9.7 (−55.1, 35.8) | 6.5 (−47.4, 60.4) | 5.7 (−51.4, 62.8) | 2.1 (−50.2, 54.5) | −20.1 (−75.4, 35.2) | 6.8 (−27.2, 40.8) |

| VPA | 12.5 (−38.2, 63.3) | 13.5 (−38.4, 65.5) | 11.5 (−31.3, 54.4) | 12.2 (−32.6, 56.9) | 10.5 (−28.8, 49.9) | 11.8 (−43.7, 67.3) | 6.0 (−34.5, 46.6) |

| MVPA | 3.3 (−17.3, 23.9) | 3.9 (−16.2, 24.0) | 18.1 (−24.2, 60.3) | 17.9 (−24.7, 60.5) | 12.7 (−26.2, 51.6) | −8.3 (−53.6, 37.0) | 12.8 (−10.6, 36.3) |

Free-Living Time in Sedentary Behavior

None of the prediction methods were significantly different from measured time in sedentary behaviors. The Cva2RM had the lowest mean error (0.6 minutes (2.1%); P≥0.05), while the other prediction methods had mean errors ranging from ±5.8 to 6.9 minutes (19.2–23.0%; P≥0.05). All prediction methods had wide 95% PIs that ranged from ±40.9 (Cva2RM) to ±43.3 (Cvm2RM) minutes.

Free-Living Time in LPA

The Puyau equation significantly underestimated measured time in LPA, during the free-living measurement, by 14.1 minutes (57%; P<0.05). The Cva2RM had the lowest mean error (−4.5 minutes (16.5%); P≥0.05), while the other prediction methods had mean errors ranging from ±6.9–12.3 minutes (25.4–45.2%; P≥0.05). All prediction methods had wide 95% PIs, ranging from ±36.9 (Cvm2RM) to ±59.7 (Treuth equation) minutes.

Free-Living Time in MPA

The Puyau equation significantly underestimated measured MPA time, during the free-living measurement, by 20.1 minutes (91.9%; p<0.05). The Trost equation had the lowest mean error (2.1 minutes (9.8%); P>0.05), while the other prediction methods the mean errors ranged from ±5.7 to 9.7 minutes (26.1% to 44.2%; p≥0.05). All prediction equations had wide 95% PIs, ranging from ±34.0 (Evenson) to ±57.1 (Treuth equation).

Free-Living Time in VPA

The Cvm2RM, Puyau equation, and Evenson cut-point were not significantly different from measured time in VPA, during the free-living measurement; however they still underestimated measured VPA time by 12.5 minutes (83.8%), 11.8 minutes (78.8%), and 6.0 minutes (40.0%), respectively (P≥0.05). The other prediction methods significantly underestimated measured VPA time by 10.5 to 13.5 minutes (70.4–90.5%; P<0.05). The 95% PIs, ranged from ±39.3 (Trost equation) to ±55.5 (Puyau equation) minutes.

Free-Living Time in MVPA

The Freedson, Treuth, and Trost equations significantly underestimated measured MVPA time by 12.7 to 18.1 minutes (34.4–49.0%; p<0.05). The Cvm2RM, Cva2RM, Puyau equation, and Evenson cut-point were within 3.3 (8.8%), 3.9 (10.5%), −8.3 (22.5%), and 12.8 (34.6%) minutes, respectively (P≥0.05). The 95% PIs ranged from ±20.1 minutes (Cva2RM) to ±45.3 minutes (Puyau equation).

DISCUSSION

This study describes the validity of seven different child-specific prediction methods (Cvm2RM, Cva2RM, Freedson child equation, Treuth equation, Trost equation, Puyau equation, and Evenson cut-points), for use with the ActiGraph accelerometer, during structured and free-living activities. The primary findings of the study are: 1) the Cvm2RM and Puyau equation provided the closest estimate of measured METRMR across the eight structured activities; 2) the Puyau equation had the lowest mean error for METRMR during the free-living measurement, but it also had the second highest RMSE, while the Cvm2RM and Cva2RM had the lowest RMSE for METRMR. In addition, the Cvm2RM and Puyau methods were the only ones not significantly different from the measured values; 3) based on the mean bias and 95% PI, the Cva2RM provided the closest estimates to measured time spent in sedentary behaviors, LPA, and MVPA during the free-living measurement, while the Evenson cut-points provided the closest estimate of MPA and VPA during the free-living measurement; and 4) none of the prediction methods worked well for estimating VPA during the free-living measurement.

This is the first study to examine the validity of the Cvm2RM and Cva2RM in an independent sample using different structured activities than what the models were developed with. The current study shows that in an independent sample of children performing different activities, the Cvm2RM and Cva2RM had similar mean errors and RMSE as the other single regression equations during the structured activities, indicating that the original cross-validation study may have been biased due to the same activities being used to validate the regression methods.

Given that validation of regression models during structured activities does not always show how the models will work in a free-living environment; we had the children perform approximately two hours of unstructured free-living activity. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the validity of the ActiGraph prediction methods during free-living activity in children, using indirect calorimetry as the criterion measure. All of the prediction equations underestimated the mean METRMR value during the free-living measurement by 0.6–1.3 METRMR (only the Puyau equation and Cvm2RM were not significantly different from measured METRMR). The Cvm2RM and Cva2RM had the lowest RMSE for estimating mean METRMR during the free-living measurement showing that they were the most precise for estimating METRMR during free-living activity. However, there were large individual errors for estimating METRMR for all prediction methods. This is in agreement with previous research showing that accelerometer estimates of EE may work well on a group basis, but lack precision at the individual level (5, 6, 25).

Time spent in sedentary behaviors, LPA, MPA, VPA, and MVPA were examined by looking at the mean bias and 95% PIs. During the free-living measurement, none of the prediction methods estimated measured time in VPA accurately and on average only estimated 1.4–4.4 minutes compared to the measured VPA time of 15.0 minutes. The Evenson cut-point provided the closest estimate of VPA and was within six minutes of measured time; however there were still large individual errors (95% PI ± 40.6 minutes). Overall, the Cva2RM provided the closest estimate of measured time spent in sedentary behaviors during the free-living measurement period. For time spent in LPA, MPA, and MVPA the Cva2RM and Cvm2RM had similar mean errors and 95% PIs and overall provided the closest estimates of measured time. As was seen with the prediction of METRMR during the free-living measurement, there were large individual errors by all prediction methods, for estimating time spent in each intensity category; however, For estimating time spent in MVPA, the Cvm2RM, Cva2RM, and Evenson cut-point had approximately 50% lower individual errors compared to the other prediction equations but it should be noted that the Evenson cut-point had a mean error three times greater than the Cvm2RM and Cva2RM.

It has been suggested that the use of tri-axial accelerometers may provide better estimates of PA than using a single axis accelerometer (2, 9, 19, 29). In children, it is suspected that a tri-axial accelerometer would more accurately detect the movement patterns during free play activities (e.g., short sporadic bursts and varied movements in multiple planes) (1). In the original cross-validation of the Cvm2RM and Cva2RM, the Cvm2RM had a lower mean bias for estimating METRMR of the structured activities, compared to the Cva2RM, which was in agreement with previous research showing that using three axes is better for PA estimates than using a single axis. The current study has conflicting results showing that the Cvm2RM had the best precision (i.e. lowest RMSE) for estimating METRMR during the free-living measurement; supporting that a tri-axial accelerometer may work better. In contrast, examination of the time spent in each PA intensity category shows that the Cva2RM works the same or better than the Cvm2RM and the other single regression equations. It appears that for estimates of EE, a tri-axial accelerometer may be more precise, however for estimates of time spent in activity categories, the use of a single axis provides similar, and in some cases, more precise estimates. The conflicting results may be partially due to the use of static regression equations and potentially when more advanced machine learning techniques (e.g. artificial neural networks (ANN)) are developed the additional input from the other axes may provide additional information needed to improve the prediction accuracy. Recently, Trost and colleagues provided preliminary evidence for the use of ANN to classify PA intensity and estimate EE in children using a waist-mounted single axis ActiGraph accelerometer (27). Results of their study show that during structured PA, classification of PA type exceeded 80%, and the ANN worked significantly better than the Trueth (22) and Freedson (11) equations for estimating EE. Further research is needed using more advanced statistical techniques to examine if using multiple axes provides more accurate estimates of PA versus using only a single axis.

The current study does have strengths and weaknesses. Strengths of the study are: 1) use of a large independent sample of children, with a wide range of age and BMI levels; 2) use of different structured activities than what the models were developed with; and 3) this is the first study to use indirect calorimetry to validate the prediction methods during free-living activity. Limitations to the current study are a limited number of structured activities, which included only one vigorous activity. In addition, while the use of a free-living measurement is a strength to the study, the children were restricted to activities that could be performed on the college campus or public school campus where they were tested. As a result, the variation in free-living activities performed by the children was reduced with the majority of the time spent by the participants in either sedentary activities or recreational sports or interactive games; however the children did freely choose what they wanted to do during this time. An additional limitation to the study is that we relied on the children to tell us when their last meal was and when they last performed previous VPA; thus it is possible that the measured resting values are higher than expected for some due to not following the protocol as asked. This has potential to affect the activity METRMR values since an elevated resting METRMR value would result in a lower activity METRMR value.

In conclusion, the Cvm2RM and Cva2RM have similar mean errors as other single regression prediction equations during structured PAs. During the free-living measurement period, the Cva2RM and Cvm2RM have the lowest mean error and individual error for estimating METRMR and time spent in sedentary behaviors, LPA, MPA, and MVPA. Further work is needed to develop machine learning techniques (e.g. artificial neural networks), which have potential to improve the precision and individual prediction error.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an NIH grant no. NIH 5R21HL093407. No financial support was received from any of the activity monitor manufacturers, importers, or retailers. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

The authors would like to thank the research participants and Prince Owusu, Larry Kennard, Katie Dooley, Shawn Pedicini, Rachel Mclellan, and Sarah Sullivan for help with data collection.

Footnotes

Disclosure: There are no declared conflicts of interest for any of the authors.

References

- 1.Bailey RC, Olson J, Pepper SL, Porszasz J, Barstow TJ, Cooper DM. The level and tempo of children’s physical activities: an observational study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(7):1033–41. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199507000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouten CV, Westerterp KR, Verduin M, Janssen JD. Assessment of energy expenditure for physical activity using a triaxial accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26(12):1516–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Internet] About BMI for Children and Teens. 2011 Feb 1; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html.

- 4.Crouter SE, Clowers KG, Bassett DR., Jr A novel method for using accelerometer data to predict energy expenditure. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100(4):1324–31. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00818.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crouter SE, DellaValle DM, Haas JD, Frongillo EA, Bassett DR. Validity of ActiGraph 2-Regression Model and NHANES Cut-Points for Assessing Free-Living Activity. J Phys Act Health. 2012 doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.4.504. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crouter SE, Horton M, Bassett DR., Jr Use of a Two-Regression Model for Estimating Energy Expenditure in Children. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2012;44(6):1177–85. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182447825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crouter SE, Kuffel E, Haas JD, Frongillo EA, Bassett DR., Jr Refined 2-regression model for the ActiGraph accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(5):1029–37. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c37458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Graauw SM, de Groot JF, van Brussel M, Streur MF, Takken T. Review of prediction models to estimate activity-related energy expenditure in children and adolescents. Int J Pediatr [Internet] 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/489304. [cited 2012 May 25];2010(Article ID 489304). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=20671992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Eston RG, Rowlands AV, Ingledew DK. Validity of heart rate, pedometry, and accelerometry for predicting the energy cost of children’s activities. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84(1):362–71. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.1.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evenson KR, Catellier DJ, Gill K, Ondrak KS, McMurray RG. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J Sports Sci. 2008;26(14):1557–65. doi: 10.1080/02640410802334196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedson P, Pober D, Janz KF. Calibration of accelerometer output for children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(11 Suppl):S523–30. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185658.28284.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freedson PS, Lyden K, Kozey-Keadle S, Staudenmayer J. Evaluation of artificial neural network algorithms for predicting METs and activity type from accelerometer data: validation on an independent sample. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(6):1804–12. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00309.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jago R, Zakeri I, Baranowski T, Watson K. Decision boundaries and receiver operating characteristic curves: new methods for determining accelerometer cutpoints. J Sports Sci. 2007;25(8):937–44. doi: 10.1080/02640410600908027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malina RM, Bouchard C, Bar-Or O. Growth, Maturation, and Physical Activity. 2. Champaign, Ill: Human Kinetics; 2004. p. 728. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattocks C, Leary S, Ness A, Deere K, Saunders J, Tilling K, Kirkby J, Blair SN, Riddoch C. Calibration of an accelerometer during free-living activities in children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2007;2(4):218–26. doi: 10.1080/17477160701408809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pober DM, Staudenmayer J, Raphael C, Freedson PS. Development of novel techniques to classify physical activity mode using accelerometers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(9):1626–34. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000227542.43669.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puyau MR, Adolph AL, Vohra FA, Butte NF. Validation and calibration of physical activity monitors in children. Obes Res. 2002;10(3):150–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puyau MR, Adolph AL, Vohra FA, Zakeri I, Butte NF. Prediction of activity energy expenditure using accelerometers in children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(9):1625–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowlands AV, Thomas PW, Eston RG, Topping R. Validation of the RT3 triaxial accelerometer for the assessment of physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(3):518–24. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000117158.14542.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schofield WN. Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr. 1985;39 (Suppl 1):5–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staudenmayer J, Pober D, Crouter S, Bassett D, Freedson P. An artificial neural network to estimate physical activity energy expenditure and identify physical activity type from an accelerometer. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107(4):1300–7. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00465.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treuth MS, Schmitz K, Catellier DJ, McMurray RG, Murray DM, Almeida MJ, Going S, Norman JE, Pate R. Defining accelerometer thresholds for activity intensities in adolescent girls. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(7):1259–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–8. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trost S. State of the art reviews: Measurement of physical activity in children and adolescents. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2008;1(4):299–314. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trost SG, Loprinzi PD, Moore R, Pfeiffer KA. Comparison of accelerometer cut points for predicting activity intensity in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1360–8. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318206476e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trost SG, Ward DS, Moorehead SM, Watson PD, Riner W, Burke JR. Validity of the computer science and applications (CSA) activity monitor in children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(4):629–33. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199804000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trost SG, Wong WK, Pfeiffer KA, Zheng Y. Artificial neural networks to predict activity type and energy expenditure in youth. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2012;44(9):1801–9. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318258ac11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [Internet] Atlanta: 2008 physical activity guidelines for Americans. Available from: http://www.health.gov/paguidelines.

- 29.Welk GJ, Corbin CB. The validity of the Tritrac-R3D Activity Monitor for the assessment of physical activity in children. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1995;66(3):202–9. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1995.10608834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]