Abstract

Background

Prolonged healing and persistent inflammation following surgery for rhinosinusitis impacts patient satisfaction and healthcare resources. Cytokines interleukin (IL)-4, 5, and 13 are important mediators in Th2 inflammatory rhinosinusitis. Decreased wound healing has been demonstrated with Th2 cytokine exposure, but this has not been extensively studied in sinonasal epithelium. We hypothesized that in vitro exposure of primary sinonasal epithelial cell cultures to Th2 inflammatory cytokine IL-4 and IL-13 would impair wound resealing and decrease expression of annexin A2 at the wound edge.

Methods

Following 24-hour exposure to IL-4, 5, or 13 versus controls, sterile linear mechanical wounds were created in primary sinonasal epithelial cultures (n = 12 wounds per condition). Wounds were followed for 36 hours or until complete closure and residual wound areas were calculated by image analysis. Group differences in annexin A2 were assessed by immunofluorescence labeling, confocal microscopy, and Western blots.

Results

Significant wound closure differences were identified across cytokine exposure groups (p<0.001). Mean percentage wound closure at the completion of the 36-hour timecourse was 98.41% ± 3.43% for control wounds versus 85.02% ± 18.46% for IL-4 exposed wounds. IL-13 did not significantly impair sinonasal epithelial wound resealing in vitro. Annexin A2 protein levels were decreased in IL-4 treated wounds when compared to control wounds (p<0.01).

Conclusions

Th2 cytokine IL-4 decreases sinonasal epithelial wound closure in vitro. Annexin A2 is also diminished with IL-4 exposure. This supports the hypothesis that IL-4 exposure impairs sinonasal epithelial wound healing and may contribute to prolonged healing in Th2 inflammatory rhinosinusitis.

Keywords: Epithelial cell, wound healing, cytokine, inflammation, interleukin 4, IL-4, annexin A2, Th2 inflammation, rhinosinusitis

BACKGROUND

With over 90% symptom relief reported, endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) is commonly employed for medically refractory chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS).1 Over 250,000 endoscopic sinus surgeries are performed in the U.S. annually, and this number appears to be increasing.2 A recent report by Venkatraman and colleagues noted that the per capita ESS rate in Medicare beneficiaries increased 19% from 1998 to 2006, despite a relatively stable rate of CRS diagnosis over the same period.3

Postoperative sinonasal mucosal healing often proceeds without incident. However, certain patients exhibit prolonged healing, persistent mucosal edema and inflammation, and lasting paranasal sinus symptoms following sinus surgery. The underlying reasons for these prolonged healing issues are not entirely clear and have been relatively understudied. Small clinical studies have shown benefit in post-ESS healing with antibiotic treatment, certain types of nasal dressings, and topical steroid therapy.4–7 In contrast, cigarette smoke exposure results in poorer outcomes in children undergoing sinus surgery and poor ciliary regeneration following sinus surgery.8–10

The underlying CRS inflammatory microenvironment likely influences postoperative sinonasal mucosal healing as well. Amongst CRS inflammatory phenotypes, a T-helper (Th)1-predominant pattern of cytokines is typically seen with infectious rhinosinusitis etiologies, whereas a Th2 pattern is evident in allergic and eosinophilic sinonasal inflammation. The precise effects of Th1 versus Th2 skewing on sinonasal epithelial wound healing at the cellular level are largely unknown at this time. Numerous cytokines, cellular mediators of inflammation, and growth factors are found in CRS and nasal polyposis, representing both the Th1 and Th2 arms of the inflammatory milieu.11,12 Soluble mediators often associated with a Th1-predominant inflammatory profile in CRS are interferon (IFN)-γ and transforming growth factor β. Conversely, Th-2 mediators found in CRS include interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-13. IL-5 and IL-13 are commonly reported to be elevated in Th-2 predominant CRS phenotypes, such as CRS with nasal polyposis and eosinophilia.13–16 Reports of IL-4 elevation in CRS are less frequent. However, elevated levels of IL-4 have been reported in CRS with nasal polyposis and allergy17, and also with aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease.17,18 Further, Ramanathan and colleagues have studied the effects of IL-4 exposure on sinonasal epithelial cells in an in vitro culture model.19

Certain inflammatory mediators have demonstrated profound effects on wound closure rates and wound healing properties. In cultured primary human bronchial epithelium, delayed wound resealing has been demonstrated in cells treated with TGF-β1.20 In addition, IL-4 and IL-13 exposure results in decreased epithelial migration in assays of human lung Calu-3 cell wound resealing, whereas exposure to IFN-γ enhanced cell migration compared to controls.21 Although IFN-γ alone enhances epithelial wound closure, wounds that exhibit impaired healing and reduced collagen deposition demonstrate elevated levels of IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in combination.22 At the cellular level, sinonasal epithelial wound resealing studies are particularly limited. Lazard and colleagues demonstrated that transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 downregulated βIV-tubulin expression in a primary human nasal epithelial wounding model.23 Tan and colleagues used an in vitro sinonasal epithelial culture system to show that nerve growth factor accelerated epithelial wound closure rates and increased expression of E-cadherin and zonnula occludens (ZO)-1 compared to controls.24

An important protein in cell migration and epithelial wound resealing is annexin A2.25 While the precise functions of annexin A2 have not been fully elucidated, this protein is known to be a calcium-dependent phospholipid binding protein involved in epithelial motility, cell matrix interactions, and actin cytoskeleton linkage to membrane protein complexes.25,26 At the cellular level, epithelial cell migration leads to wound closure. This process involves attachment and turnover of focal adhesion complexes that contact the extracellular matrix. Alterations in the expression, regulation, or interactions of focal adhesion proteins and annexin A2, often through Rho GTPase-dependent mechanisms, impact cell migration and epithelial wound healing.25, 27–29

The experiments in this study sought to expand knowledge of sinonasal epithelial healing on a cellular level. In a translational in vitro model, sinonasal epithelial wound healing properties were examined with respect to the influence of inflammatory cytokines on wound resealing and expression of annexin A2 (selected as a wound edge protein marker for epithelial cell migration).

METHODS

Study population

The Emory University Institutional Review Board granted approval for this study, and all patients donating tissue gave written informed consent. Participants were scheduled to undergo endoscopic transnasal surgery as part of treatment for orbital or skull base pathology and were without significant clinical or radiographic evidence of chronic rhinosinusitis. Exclusion criteria were the presence of any of the following: cystic fibrosis, immune deficiency, autoimmune conditions, granulomatous disorders, aspirin-exacerbated respiratory conditions or use of oral steroids within 7 days prior to surgery.

Primary sinonasal epithelial air-liquid interface cell culture

During endoscopic transnasal surgery, sinonasal tissue was biopsied from paranasal sinus mucosa and placed into RPMI 1640 media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 2X antibiotic/antimycotic (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Tissue was biopsied from the paranasal sinus lining of the ethmoid or sphenoid sinuses during the approach for the indicated surgical pathology. Tissue was not taken from the turbinates or nasal cavity. Biopsied tissue was then digested with Streptococcus griseus protease (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 90–120 minutes at 37°C or overnight at 4°C, and the digestion subsequently stopped with heat inactivated fetal bovine serum. The cell suspension was centrifuged for 5 minutes (950 rpm, 101 × g) and the pellet resuspended in Bronchial Epithelial Growth Medium (BEGM), consisting of Bronchial Epithelial Basal Medium (BEBM) supplemented with BEBM SingleQuot additives (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), antibiotic/antimycotic (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and nystatin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Epithelial cells were isolated from fibroblasts by incubating at 37°C for 2 hours in a tissue culture-treated petri dish. Following incubation, epithelial cell-rich supernatant was placed into collagen-coated T75 cell culture flasks (Corning, Corning, NY). Primary sinonasal epithelial cell cultures were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity, and BEGM media was changed every 48–72 hours.

Once the cell layers reached 85–95% confluence, cells were split to Transwell inserts (Corning, Corning, NY). Cells were maintained on Transwell inserts with BEGM on the apical and basal surfaces until confluence was confirmed by light microscopy. At confluence, apical media was removed and basal media was changed to air-liquid interface (ALI) media. The base of ALI media was a 50:50 mixture of BEBM (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) and DMEM high glucose (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). ALI media was supplemented with BEBM SingleQuots, antibiotic/antimycotic, retinol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Over the subsequent 2–6 weeks, cell layers polarized and differentiated at the air-liquid interface. Polarization and differentiation was confirmed by identification of beating cilia under phase-contrast light microscopy. Before use in wounding experiments, cells were allowed to stabilize for at least 6–10 additional days. These primary sinonasal epithelial culture methods are based upon the methods of Lane and colleagues.30

In vitro sinonasal epithelial wounding experiments

Confluent, mature, polarized, differentiated, ciliated primary sinonasal epithelial cell cultures were initially exposed to chosen cytokines for 24 hours prior to wounding. Cytokines are added to ALI media at the following final concentrations: recombinant human IL-4 (50 ng/ml, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN)21,31, recombinant human IL-5 (200 ng/ml, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN)32, recombinant human IL-13 (50 ng/ml, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN)21, wound closure inhibitor combination positive control IFN-γ (100 IU/ml, Genentech, San Francisco, CA) and recombinant human TNF-α (500 ng/ml, BioVision, Mountain View, CA). Chosen concentrations are moderate to high concentrations in order to appropriately stimulate an effect, as available tissue and resources did not allow for extensive dose finding studies.

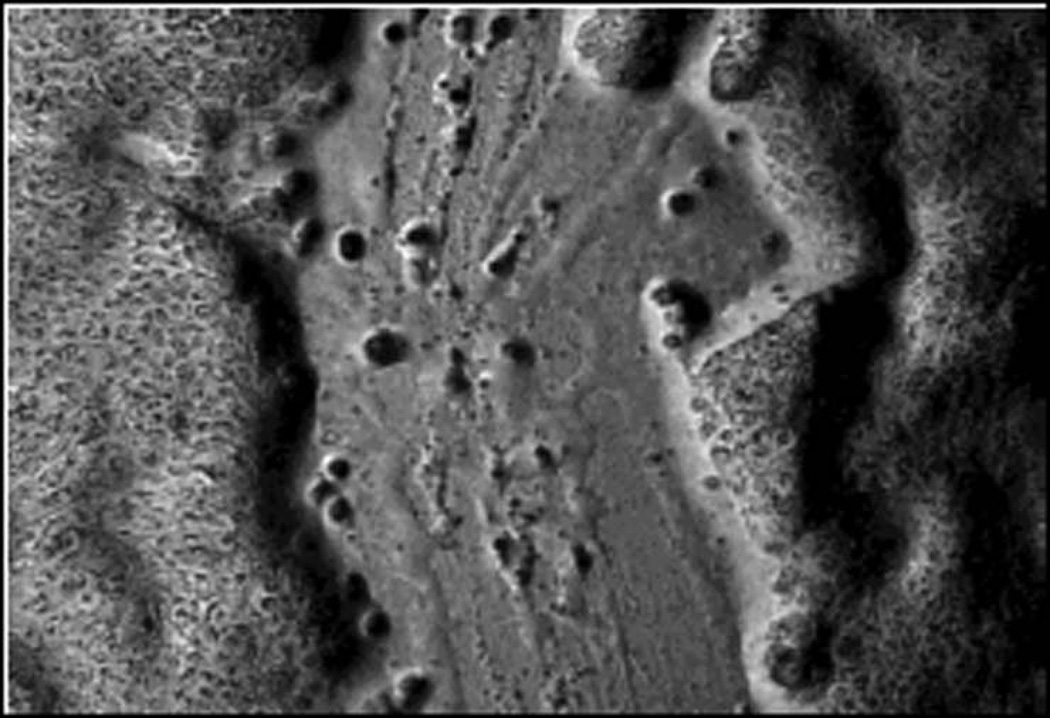

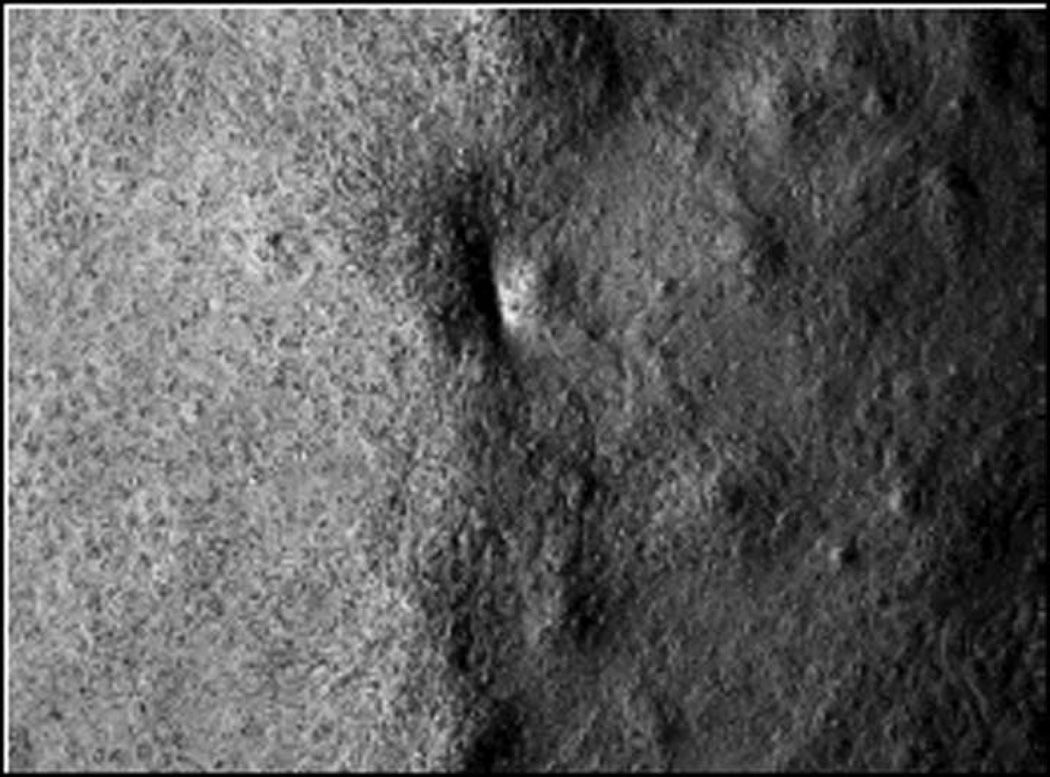

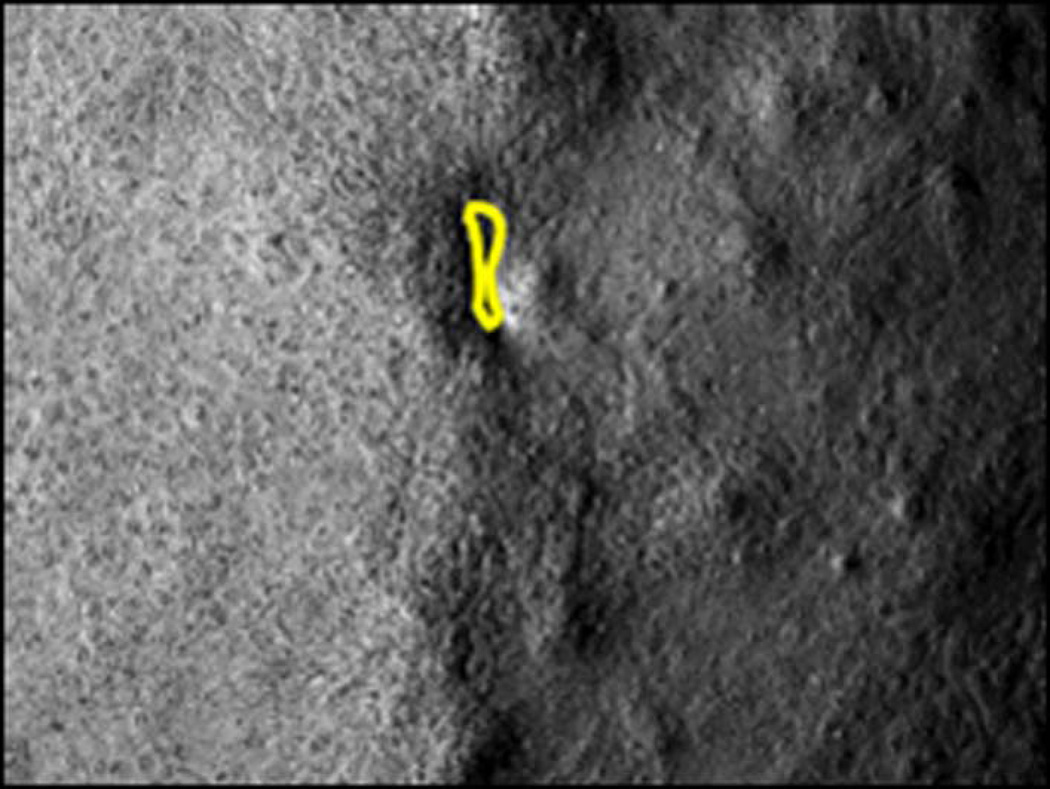

After 24-hour cytokine exposure, sterile linear mechanical wounds were created in the sinonasal epithelial cell layers. A total of 12 wounds per cytokine exposure group were performed for analysis. Every 4 hours for 36 hours, microscopic photographs of each wound were taken with a Zeiss Axiovert 35 microscope with MRc5 AxioCam (Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY), providing images at 9 post-wound time points. Using ImageJ image analysis software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) wound edges were outlined, and wound area was recorded for each picture. Wounds were followed until the 36-hour post-wounding time point or until complete wound closure. (FIGURE 1) Throughout the wounding experiments, cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity unless microscopic photographs were actively being taken. Percentage wound closure was then calculated for each post-wound time point.

FIGURE 1. EXAMPLE OF WOUND AREA CALCULATION DURING TIMED SINONASAL EPITHELIAL WOUND CLOSURE EXPERIMENT.

Microscopic photograph of initial wound and 12–36 hour example photographs of the same wound during spontaneous closure. (a2–d2) Microscopic photographs of initial wound and 12–36 hour wounds with example wound edge outline overlays. Area of each wound was calculated with ImageJ image analysis program.

- a1. Initial wound

- a2. Initial wound with area outline

- b1. 12 hours post-wounding

- b2. 12 hours post-wounding with area outline

- c1. 24 hours post-wounding

- c2. 24 hours post-wounding with area outline

- d1. 36 hours post-wounding

- d2. 36 hours post-wounding with area outline

Annexin A2 protein assessment during wound closure

Based upon the sinonasal epithelial wound timecourse experiments described above, the 8–12 hour post-wounding timeframe was identified as the point at which the greatest discrepancy in wound closure rates existed amongst individual cytokine exposure groups. Further, IL-4 had the largest percentage of unhealed wounds at the 36-hour experiment end and graphically exhibited slower wound closure rates than IL-5 or IL-13. (These findings are described further in the Results section.) Therefore, IL-4 was chosen for further investigation of annexin A2 alterations during wound resealing.

Experiments for wound edge protein alterations were performed by, once again, incubating primary, mature, polarized, differentiated, ciliated sinonasal epithelial cells with IL-4, IFN-γ and TNF-α combination, or media only control for 24 hours. Sterile linear mechanical wounds were then created in the sinonasal epithelial cell layers. At the 10-hour post-wounding time point, wound closure experiments were stopped. Annexin A2 levels were assessed quantitatively via image analysis of immunofluorescence labeling and confocal microscopy, as well as semi-quantitatively via Western blotting.

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-annexin A2 was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Alexa-488 and Alexa-546-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used for immunofluorescence staining. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) were used for Western blotting. All remaining immunofluorescence staining and Western blot reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, unless stated otherwise.

Immunofluorescence labeling and confocal microscopy for in vitro wounding experiments

Sinonasal epithelial wound edge annexin A2 was examined by immunofluorescence labeling and confocal laser microscopy. Epithelial cell samples were fixed and permeabilized in methanol at −20°C. The remaining immunofluorescence staining steps were performed at room temperature. Following fixation, samples were washed with HBSS with Mg2+ and Ca2+ (HBSS+). Non-specific staining was blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in HBSS+. Annexin A2 primary antibody was diluted in blocking buffer at 1:50. Samples were incubated with primary antibodies, washed in HBSS+, and subsequently incubated with Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (1:500 in blocking buffer). Samples were washed a final time in HBSS+, mounted on slides with p-phenylenediamine anti-quench reagent, and sealed.

Stained cell layers were examined using a Zeiss LSM510 laser scanning confocal microscope coupled to a Zeiss 100M Axiovert with a 40× Pan-Apochromat oil lens. Fluorescent dyes were imaged sequentially to eliminate cross talk between channels, and images were processed with Zeiss LSM5 image browser software.

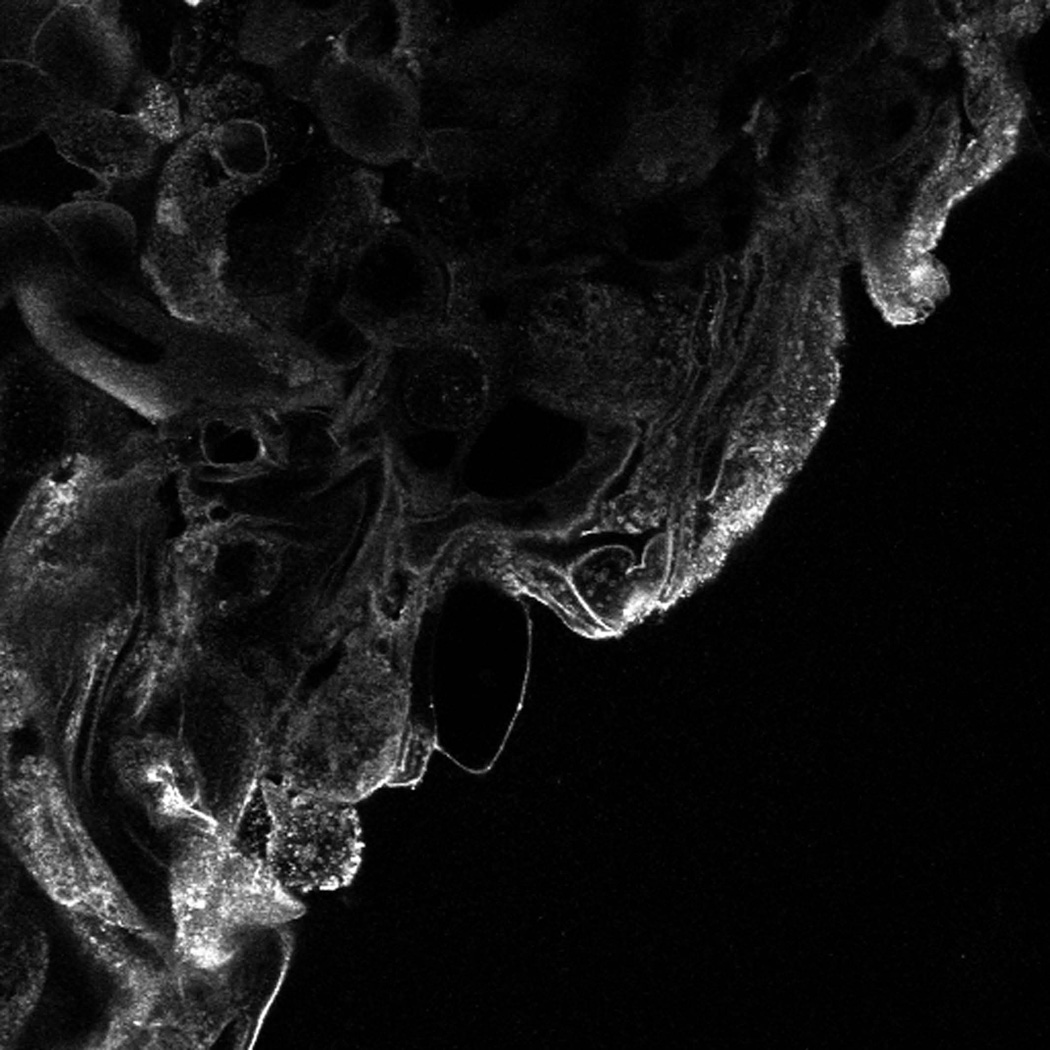

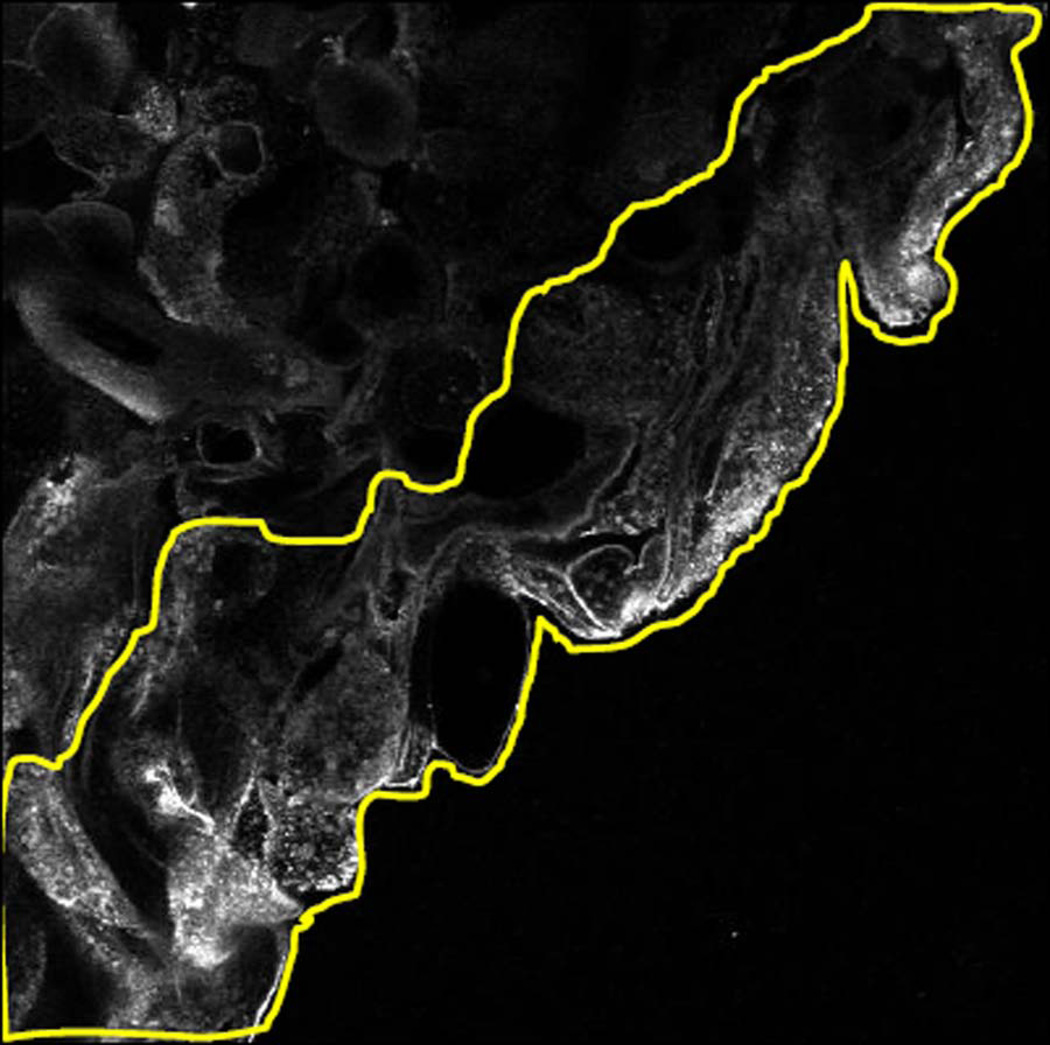

In order to provide quantitative assessments of specific protein changes at epithelial wound edges by cytokine exposure group during active wound healing, a single representative wounding experiment, stopped during active wound healing at approximately 10 hours post-wounding, was performed as described above. Eight to ten confocal microscopy wound edge photographs were taken for each cytokine exposure condition. The wound edge photographs were taken from multiple wounds for each cytokine exposure condition in order to provide a representative sample of wound edges. However, in order to reduce staining and confocal microscopy variability as much as possible, all aspects of the experiment were performed on the same day across cytokine exposure groups: epithelial wounding, immunofluorescence staining, and confocal imaging. Further, confocal microscopy settings were standardized to a single control wound edge image and the same settings were used across all cytokine exposure conditions.

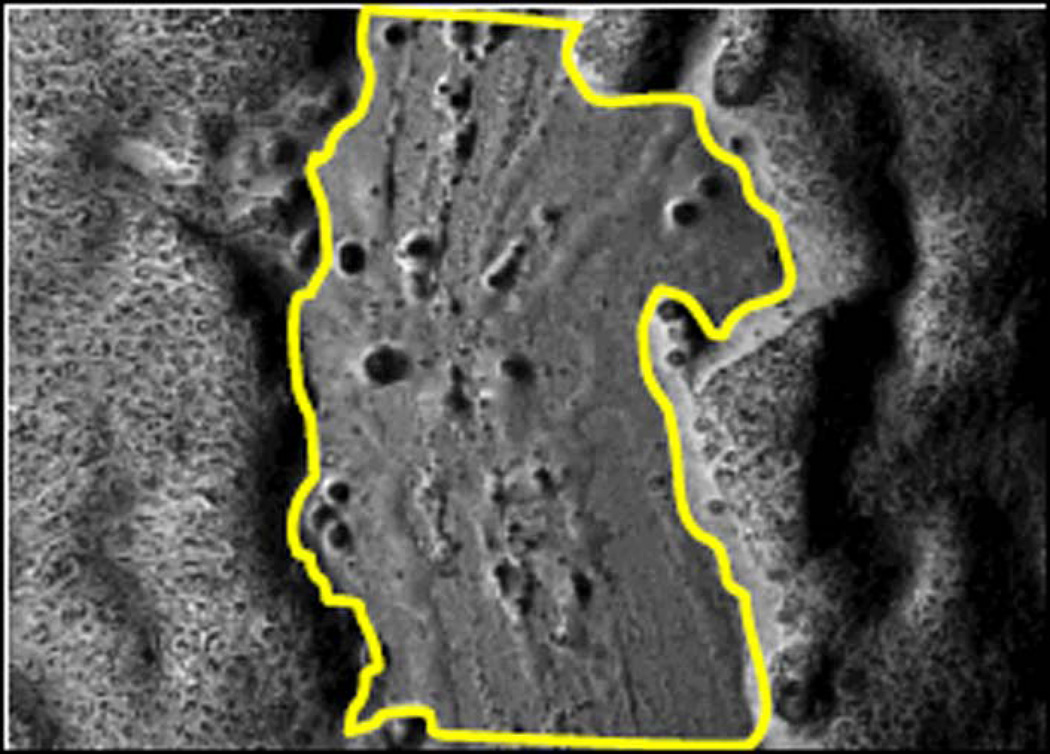

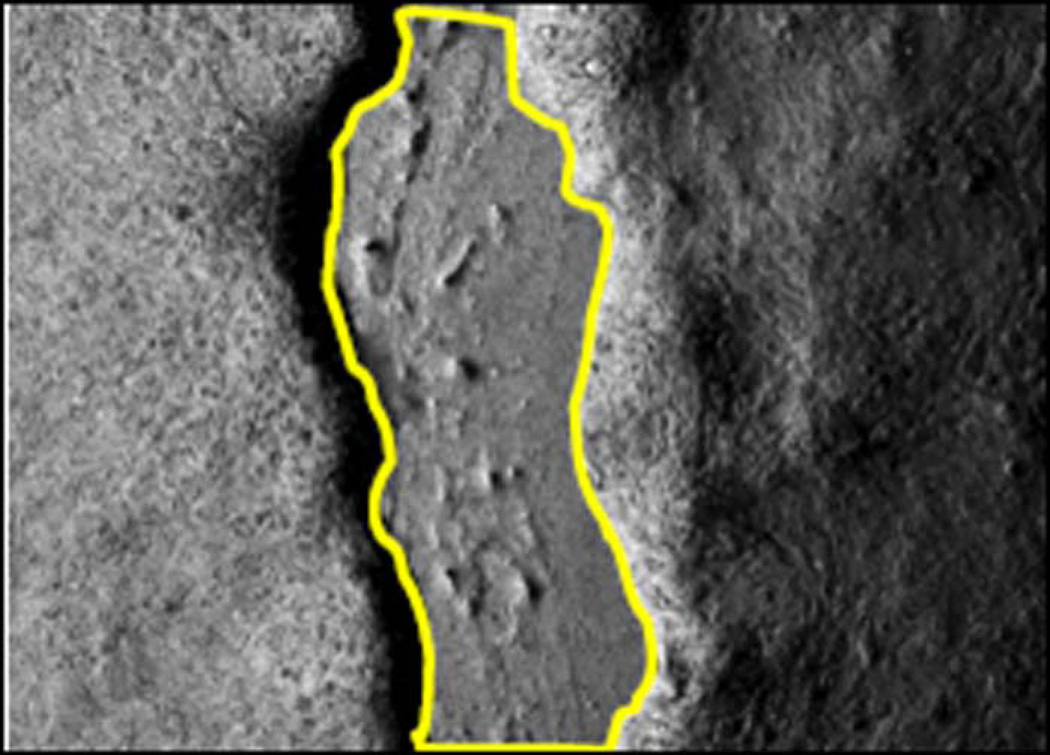

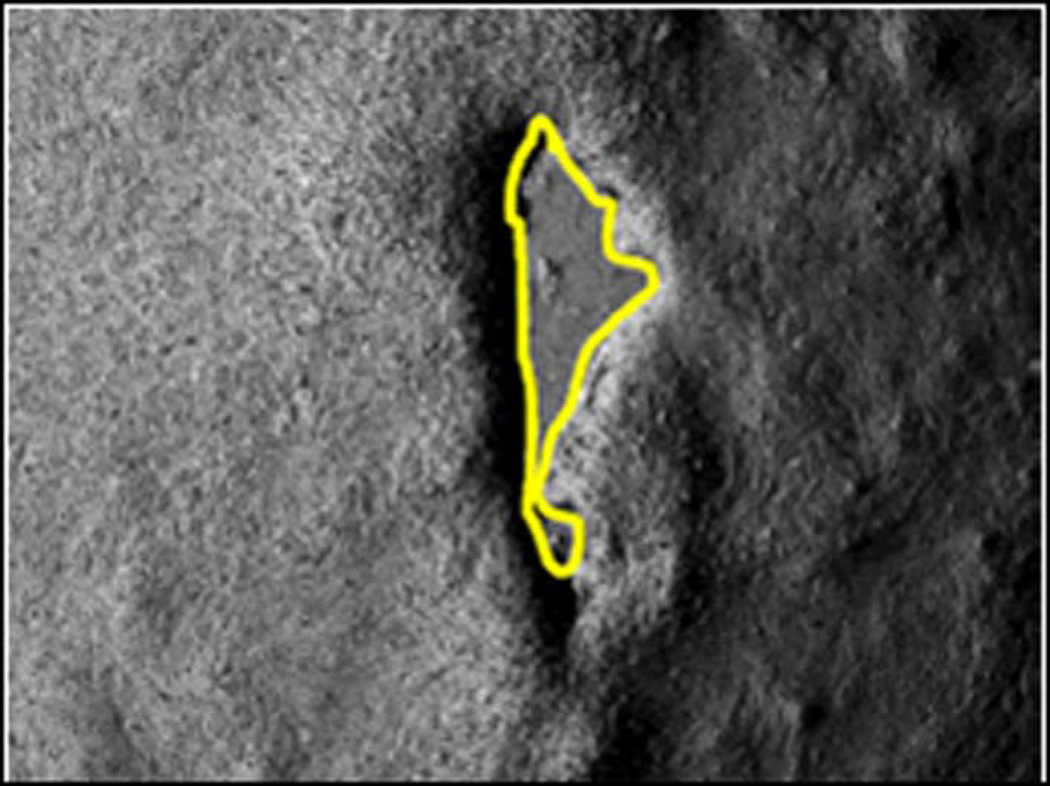

Quantitative pixel intensity analysis was performed with the ImageJ image analysis software. The wound edge epithelial area was outlined on the ImageJ program. Pixel density was recorded for the outlined area, and the pixel density was divided by the outlined wound edge area. Pixel density per area differences were compared amongst cytokine exposure groups for each specified protein. (FIGURE 2)

FIGURE 2. EXAMPLE OF SINONASAL EPITHELIAL WOUND EDGE PIXEL ANALYSIS.

(a) Sinonasal epithelial wound edge confocal microscopy image. All images for experiments in this series were taken at 40X magnification. Images are converted to grayscale for pixel intensity analysis. Immunofluorescence staining was performed with anti-annexin A2 antibody in this image. (b) Approximately 2 cell layers at wound edge are outlined with image analysis software. Pixel density is calculated per area of wound edge for each confocal microscopy image.

Cell lysis and Western blotting for in vitro wounding experiments

To further assess annexin A2 protein differences during active wound closure across cytokine exposure groups, Western blotting was performed for protein semi-quantitation. At the 10-hour post-wounding time point, cells were washed with HBSS+ and scraped into RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 1% Na deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, pH 7.4) with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Complete cell lysis was ensured by sonicating samples on ice and incubating for 10 minutes at 4°C. Nuclear debris was removed from samples by centrifugation (1,000 × g for 5 minutes, then 4,500 × g for 10 minutes), and sample protein concentrations were normalized by bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Lysates were boiled in SDS sample buffer containing 10% 2-mercaptoethanol for 10 minutes. Protein samples were run on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for Western blotting.

Primary annexin A2 antibody for Western blots was used at 1:500. Protein loading control for these experiments was glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), which demonstrates little fluctuation with active epithelial cell migration. Finally, to ensure protein fluctuations were seen as the result of epithelial cell migration and wound healing rather than cell death, apoptosis marker poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) levels were also assessed by Western blot.

Semi-quantification of Western blot protein levels was performed for each experimental run by using image analysis to normalize protein density for annexin A2 to the GAPDH protein loading control for that experiment. Normalized protein levels were collated across 3 experimental runs in order to provide representative distributions of protein density. These experiments were performed in order to assess protein levels by a method complimentary to immunofluorescence labeling. No statistical analysis was performed for Western blot experiments due to small sample sizes.

Statistical Analysis

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences in wound closure over time (within-group, repeated measure), cytokine group differences (between-group), and any interactions between these measures. Statistical significance for the overall ANOVA was set a p<0.05. Although group sizes of 12 wounds per group are somewhat small and it is difficult to ensure a normal distribution in wound closure percentage values amongst the population from which these samples are drawn, a repeated-measures ANOVA was chosen for statistical analysis after consideration of various alternatives. First, an assessment of normal data distribution was performed for each cytokine exposure group at each post-wounding time point, and most of the individual sample sets were normally distributed. Second, there is no non-parametric equivalent that would be appropriate for an analysis of this kind. Although a combination Kuskall-Wallis and Friedman nonparametric testing would be able to assess for individual main effects of wound closure percentage over time and cytokine group differences, these tests are not able to evaluate time-group interaction as the repeated measures ANOVA can. The importance of identifying time-group interactions is integral to appropriately assessing the outcome of individual cytokine effects on sinonasal epithelial wound closure in this study.

For immunofluorescence pixel density analysis, statistical analysis was performed with non-parametric Kruskall-Wallis testing across all cytokine exposure groups with post-hoc Mann Whitney U testing to determine individual group differences. Differences were considered statistically significant when the p-value was <0.05.

RESULTS

Cytokine effects on sinonasal epithelial wound resealing

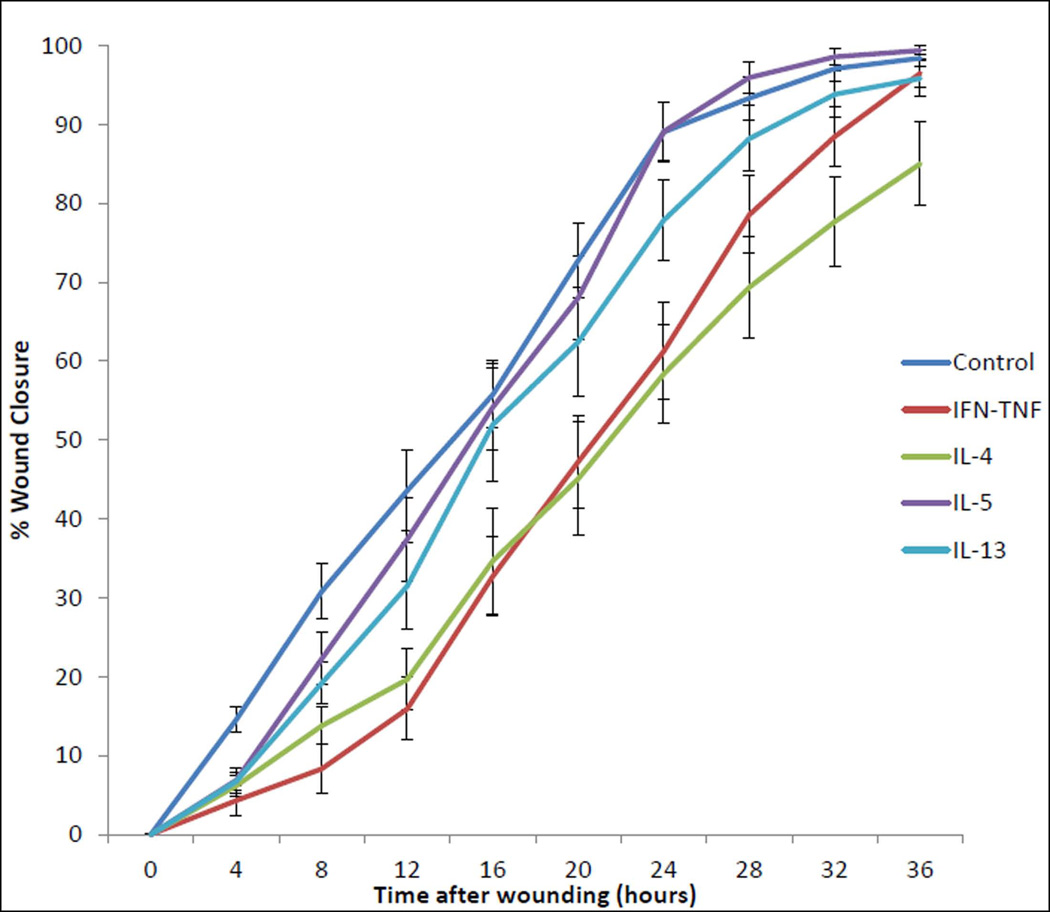

To examine the influence of Th2 cytokines on sinonasal wound resealing in vitro, timecourse studies were performed during active wound closure. Initial data analysis assessed the mean percentage of wound closure, as calculated by dividing the area of residual wound by the area of the initial wound and subtracting from 100. As expected, ANOVA revealed that all cytokine exposure groups and the media-only control exhibited wound closure over time; the mean percentage wound closure within each exposure group increased significantly over the 36-hour course of the experiment (p<0.001). There was, however, a significant difference in wound closure percentage across cytokine exposure groups (p<0.001). First, the media-only control wound closure percentage was significantly different from that of the positive control IFNγ-TNFα exposure (p=0.005), indicating good experimental conditions. Next, as hypothesized, wound closure percentage with IL-4 exposure was significantly less than the media-only control (p=0.001). Wound closure percentage with IL-5 exposure was not significantly different from the media-only control. Wounds exposed to IL-5 had higher closure percentage than wounds exposed IFNγ-TNFα (p=0.023) and IL-4 (p=0.005). Unexpectedly, the IL-13 exposure group was not significantly different from any of the other exposure conditions. (FIGURE 3) The overall results of these timecourse experiments indicate that IL-4 exposure inhibited sinonasal epithelial wound closure in vitro.

FIGURE 3. REPEATED MEASURES IN VITRO SINONASAL EPITHELIAL WOUND HEALING STUDY FOLLOWING 24-HOUR CYTOKINE EXPOSURE.

This chart graphically represents the mean percentage of sinonasal epithelial wound closure under 5 cytokine exposure conditions for the 36-hour post-wounding timecourse. Cytokine exposure groups are denoted by colored lines. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Although there are significant effects of time and overall cytokine exposure group in the timed sinonasal epithelial wound closure analysis described above, the most crucial finding in the repeated measures ANOVA is the significant time by cytokine exposure interaction (p<0.001). Post-hoc analysis reveals that multiple individual significant differences exist across all post-wounding time points from 8 to 36 hours. (TABLE 1) There were no significant cytokine group differences at the 4-hour post-wounding time point. Again indicating relatively good experimental conditions, the positive control IFNγ-TNFα exposure was significantly different from the media-only control at all post-wounding time points from 8 to 28 hours. The IL-4 exposure group differed from the media-only control group at all post-wounding time points after 4 hours. The IL-5 and IL-13 exposure groups and exhibited various significant differences versus the IFNγ-TNFα and IL-4 exposure groups across numerous post-wounding time points from 8 to 36 hours.

TABLE 1.

WOUND RESEALING GROUP DIFFERENCES BY CYTOKINE EXPOSURE.

| Vs. Control | Vs. IFNγ-TNFα | Vs. IL-4 | Vs. IL-5 | Vs. IL-13 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference | Mean difference | Mean difference | Mean difference | Mean difference | ||

| Timepoint | Mean | |||||

| 4 hrs. | ||||||

| Control | 14.53 | ---- | 10.23 | 8.36 | 7.69 | 6.82 |

| IFNγ-TNFα | 4.30 | 10.23 | ---- | 1.87 | 2.54 | 3.41 |

| IL-4 | 6.17 | 8.36 | 1.87 | ---- | 0.67 | 1.54 |

| IL-5 | 6.84 | 7.69 | 2.54 | 0.67 | ---- | 0.87 |

| IL-13 | 7.71 | 6.82 | 3.41 | 1.54 | 0.87 | ---- |

| 8 hrs. | ||||||

| Control | 30.77 | ---- | 22.44* | 17.00* | 8.51 | 11.61 |

| IFNγ-TNFα | 8.33 | 22.44* | ---- | 5.44 | 13.93* | 10.83 |

| IL-4 | 13.77 | 17.00* | 5.44 | ---- | 8.49 | 5.39 |

| IL-5 | 22.26 | 8.51 | 13.93* | 8.49 | ---- | 3.10 |

| IL-13 | 19.16 | 11.61 | 10.83 | 5.39 | 3.10 | ---- |

| 12 hrs. | ||||||

| Control | 43.58 | ---- | 27.68* | 23.92* | 6.16 | 12.10 |

| IFNγ-TNFα | 15.90 | 27.68* | ---- | 3.76 | 21.52* | 15.58* |

| IL-4 | 19.66 | 23.92* | 3.76 | ---- | 17.76* | 11.82 |

| IL-5 | 37.42 | 6.16 | 21.52* | 17.76* | ---- | 5.94 |

| IL-13 | 31.48 | 12.10 | 15.58* | 11.82 | 5.94 | ---- |

| 16 hrs. | ||||||

| Control | 55.77 | ---- | 23.03* | 21.11* | 1.60 | 3.80 |

| IFNγ-TNFα | 32.74 | 23.03* | ---- | 1.92 | 21.43* | 19.23* |

| IL-4 | 34.66 | 21.11* | 1.92 | ---- | 19.51* | 17.31* |

| IL-5 | 54.17 | 1.60 | 21.43* | 19.51* | ---- | 2.20 |

| IL-13 | 51.97 | 3.80 | 19.23* | 17.31* | 2.20 | ---- |

| 20 hrs. | ||||||

| Control | 72.76 | ---- | 25.54* | 27.69* | 4.76 | 10.33 |

| IFNγ-TNFα | 47.22 | 25.54* | ---- | 2.15 | 20.78* | 15.21* |

| IL-4 | 45.07 | 27.69* | 2.15 | ---- | 22.93* | 17.36* |

| IL-5 | 68.00 | 4.76 | 20.78* | 22.93* | ---- | 5.57 |

| IL-13 | 62.43 | 10.33 | 15.21* | 17.36* | 5.57 | ---- |

| 24 hrs. | ||||||

| Control | 89.01 | ---- | 27.77* | 30.64* | 0.10 | 11.14 |

| IFNγ-TNFα | 61.24 | 27.77* | ---- | 2.87 | 27.87* | 16.63* |

| IL-4 | 58.37 | 30.64* | 2.87 | ---- | 30.74* | 19.50* |

| IL-5 | 89.11 | 0.10 | 27.87* | 30.74* | ---- | 11.24 |

| IL-13 | 77.87 | 11.14 | 16.63* | 19.50* | 11.24 | ---- |

| 28 hrs. | ||||||

| Control | 93.32 | ---- | 14.76* | 23.96* | 2.61 | 5.12 |

| IFNγ-TNFα | 78.56 | 14.76* | ---- | 9.20 | 17.37* | 9.64 |

| IL-4 | 69.36 | 23.96* | 9.20 | ---- | 26.57* | 18.84* |

| IL-5 | 95.93 | 2.61 | 17.37* | 26.57* | ---- | 7.73 |

| IL-13 | 88.20 | 5.12 | 9.64 | 18.84* | 7.73 | ---- |

| 32 hrs. | ||||||

| Control | 97.09 | ---- | 8.63 | 19.41* | 1.47 | 3.27 |

| IFNγ-TNFα | 88.46 | 8.63 | ---- | 10.78 | 10.10 | 5.36 |

| IL-4 | 77.68 | 19.41* | 10.78 | ---- | 20.70* | 16.14* |

| IL-5 | 98.56 | 1.47 | 10.10 | 20.70* | ---- | 4.74 |

| IL-13 | 93.82 | 3.27 | 5.36 | 16.14* | 4.74 | ---- |

| 36 hrs. | ||||||

| Control | 98.40 | ---- | 1.90 | 13.38* | 0.98 | 3.37 |

| IFNγ-TNFα | 96.50 | 1.90 | ---- | 11.48 | 2.88 | 1.47 |

| IL-4 | 85.02 | 13.38* | 11.48 | ---- | 14.36* | 10.01 |

| IL-5 | 99.38 | 0.98 | 2.88 | 14.36* | ---- | 4.35 |

| IL-13 | 95.03 | 3.37 | 1.47 | 10.01 | 4.35 | ---- |

This Table presents the results of Tukey post-hoc analysis calculations, which identify individual significant differences in cytokine exposure groups at each post-wounding time point. Based upon the sample size per group (n = 12) and the degrees of freedom for this data set (greater than 240), a value greater than 12.67 on the Tukey calculation indicates significant differences. The comparisons that are significant have been highlighted with bold, italics, and an asterisk.

At the completion of the cytokine exposure wound closure experiment, 9 of 12 (75%) individual media-only control wounds were completely closed. Likewise, 10 of 12 (83.3%) IL-5 exposed wounds and 9 of 12 (75%) IL-13 exposed wounds were completely closed. However, only 6 of 12 (50%) IFNγ-TNFα exposed wounds and 3 of 12 (25%) IL-4 exposed wounds were completely closed at the end of the 36-hour experiment. Mean percentage wound closure at the completion of the 36-hour timecourse was 98.41% ± 3.43% for the media-only control wounds, 99.38% ± 2.14% for IL-5 exposed wounds, 95.83% ± 7.58% for IL-13 exposed wounds, 96.50% ± 5.99% for IFNγ-TNFα exposed wounds, and 85.02% ± 18.46% for IL-4 exposed wounds. Taken together, these results indicate that exposure to IL-4 during sinonasal epithelial wound healing in vitro significantly delays wound resealing.

Annexin A2 protein assessment during in vitro sinonasal epithelial wound resealing

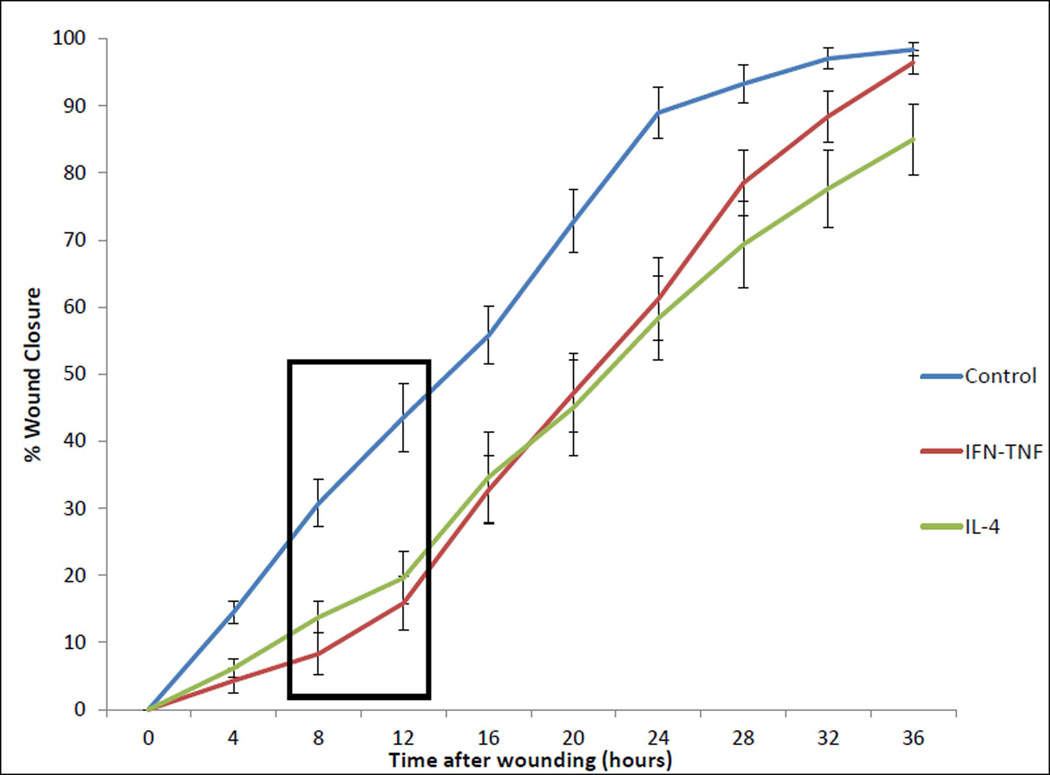

Based upon the sinonasal epithelial wound healing timecourse experiment results above, preliminary investigation of potential mechanisms for impaired wound resealing in the IL-4 cytokine exposure group was performed. The graphical representation of wound closure percentage indicates that the most disparate rates of wound resealing between media-only control and the IL-4 exposure group occurred between 8 and 12 hours post-wounding. (FIGURE 4) Therefore, the in vitro cytokine exposure sinonasal epithelial wound healing experiments were repeated as previously described, experiments were stopped at the 10-hour post-wounding time point, and annexin A2 was evaluated via immunofluorescence staining/confocal microscopy and Western blots.

FIGURE 4. REPEATED MEASURES IN VITRO SINONASAL EPITHELIAL WOUND HEALING STUDY FOLLOWING 24-HOUR CYTOKINE EXPOSURE – NO-CYTOKINE CONTROL, IFNγ-TNFα, AND IL-4 ONLY.

This chart graphically represents the mean percentage of sinonasal epithelial wound closure under cytokine exposure conditions for the 36-hours post-wounding timecourse. Cytokine exposure groups are denoted by colored lines. For better visualization of Th2 cytokine IL-4 versus no-cytokine and IFNγ-TNFα controls, IL-5 and IL-13 lines have been removed. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. A black box has been inserted to highlight the 8–12 hour post-wounding timeframe. Within this timeframe, the rate of wound closure is graphically different amongst cytokine groups. Based upon this finding, the 10-hour post-wounding time point was chosen for additional study of epithelial migratory and adherens junction protein differences during active wound healing amongst cytokine exposure groups.

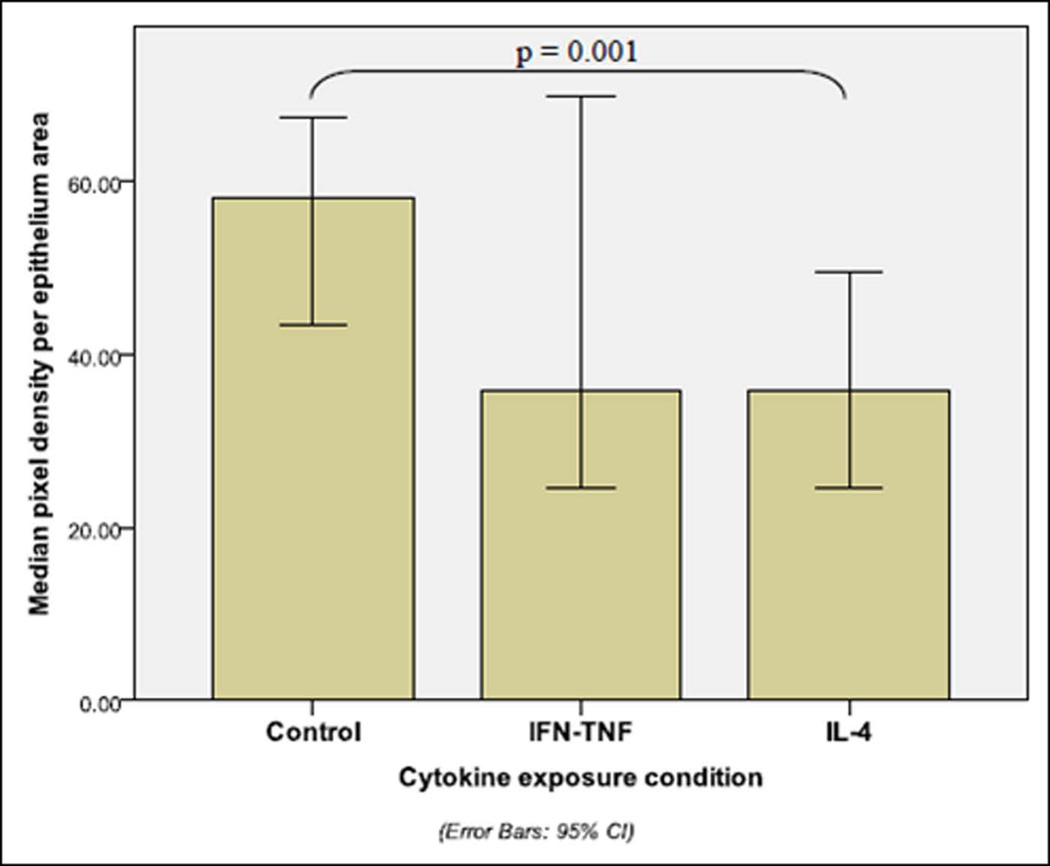

Pixel intensity analysis of sinonasal epithelial wound edges, as assessed by immunofluorescence staining/confocal microscopy revealed significant differences in annexin A2 protein levels. By Kruskall-Wallis analysis, significant protein differences were identified across cytokine exposure conditions (p=0.013). (TABLE 2) Post-hoc analysis by Mann Whitney U testing identified significant individual cytokine exposure group differences, as exhibited in Figure 5. (FIGURE 5) Annexin A2 was significantly decreased at the wound edge (p=0.001) with IL-4 exposure versus media-only control.

TABLE 2.

IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE STAINING PIXEL DENSITY ANALYSIS FOR WOUND EDGE ANNEXIN A2 FROM IN VITRO SINONASAL EPITHELIAL WOUND RESEALING STUDIES

| Inflammatory condition |

N per group | Mean pixel density per epithelium area |

Median pixel density per epithelium area |

Standard deviation |

95% confidence interval |

Range | Kruskall Wallis p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 9 | 57.50 | 58.04 | 13.81 | (48.48, 66.52) | 41.71–85.27 | 0.013* |

| IFNγ-TNFα | 9 | 43.17 | 35.79 | 23.88 | (27.57, 58.77) | 19.20–92.18 | |

| IL-4 | 10 | 34.73 | 35.71 | 11.57 | (27.56, 41.90) | 12.04–50.20 |

Statistically significant differences amongst cytokine exposure conditions are denoted by an asterisk (*).

FIGURE 5. PIXEL DENSITY ANALYSIS OF ANNEXIN A2.

This graph depicts pixel density analysis for annexin A2 protein from immunofluorescence images taken at approximately 10 hours post-wounding during in vitro cytokine exposure sinonasal wound healing studies. Median ± 95% confidence interval protein intensity is demonstrated by cytokine exposure condition. Brackets demonstrate statistical significance between cytokine exposure groups, as determined by post-hoc testing following Kruskall-Wallis analysis. (Control n = 9, IFNγ-TNFα n = 9, IL-4 n = 10; Kruskall-Wallis p = 0.013)

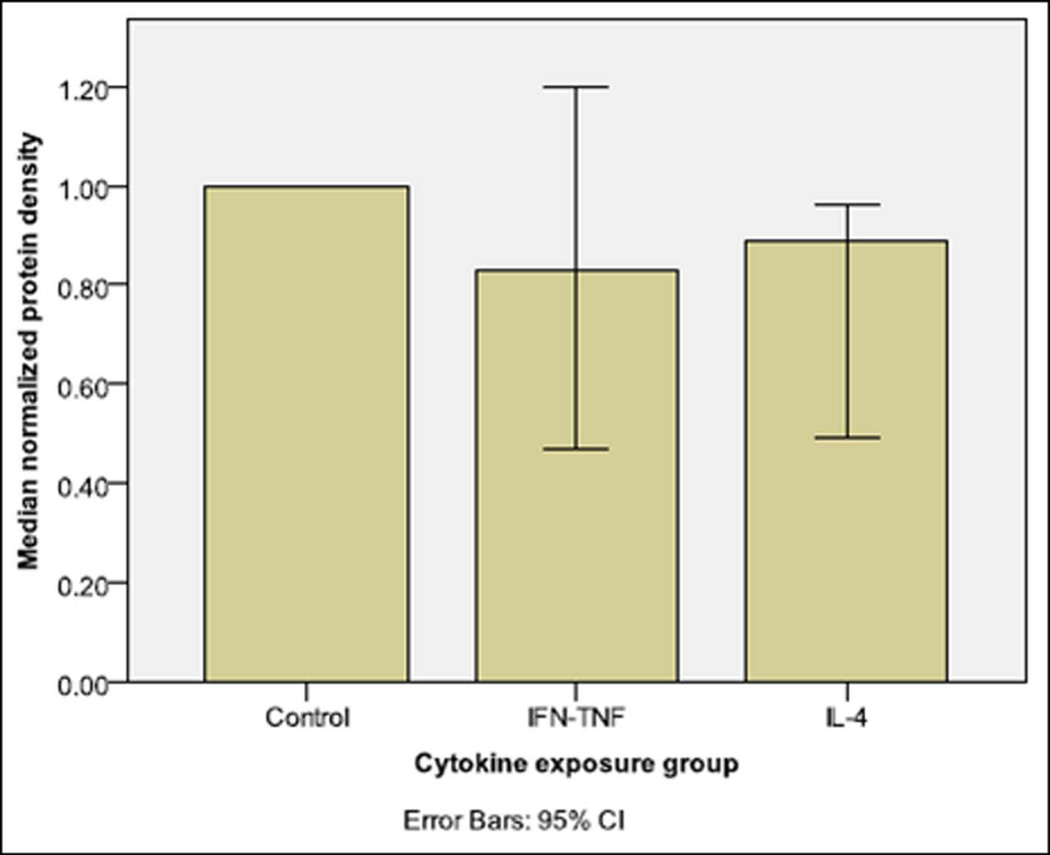

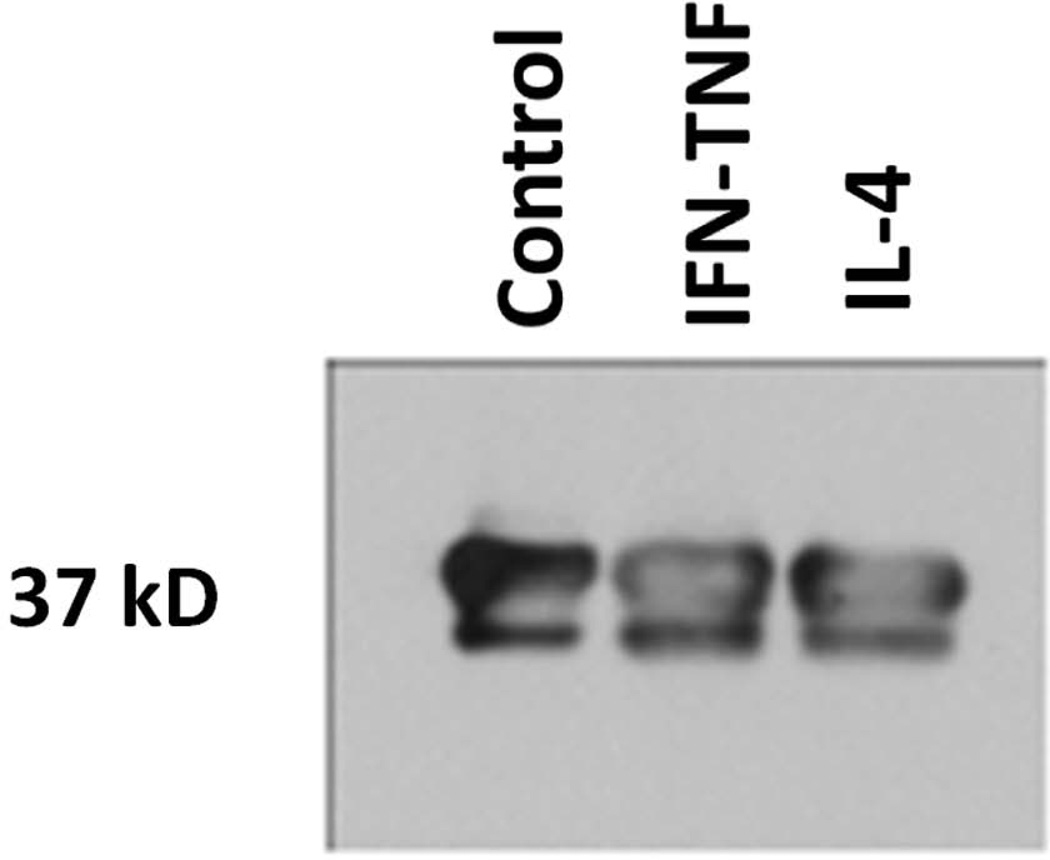

To further assess epithelial annexin A2 protein levels, Western blot analysis of annexin A2 protein levels was also performed. (FIGURE 6) Further, in each run of Western blot experiments, the density of annexin A2 protein was normalized to GAPDH protein loading control. A graphical representation of these normalized protein levels across multiple Western blot runs is also shown, in order to better demonstrate median protein level changes across experimental trials. The Western blot pattern of decrease in annexin A2 protein levels with IL-4 exposure is similar to the pattern seen in immunofluorescence staining/confocal microscopy and pixel density analysis. Due to the small number of experimental trial for Western blots (n = 3), no statistical analysis is performed. These results indicate that annexin A2 protein shows consistent decreases during active wound resealing under IL-4 exposure.

FIGURE 6. WESTERN IMMUNOBLOT ANALYSIS OF 10 HOUR POST-WOUNDING ANNEXIN A2 PROTEIN CHANGES IN IN VITRO CYTOKINE-EXPOSED SINONASAL EPITHELIAL WOUND HEALING ASSAY.

This figure demonstrates (a) combined results of Western immunoblot (graphs) for normalized annexin A2 protein levels at the 10 hour post-wounding time point in cytokine exposed sinonasal epithelial wound healing experiments (n = 3 experiments). An example annexin A2 Western immunoblot is also shown (b)

Of note, apoptosis marker poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) cleaved product levels were also assessed in Western blot analysis of wound closure experiments. No differences in PARP cleavage product levels were seen across cytokine exposure conditions, indicating that differences in annexin A2 are not likely to be due to differences in cell death across cytokine exposure groups.

DISCUSSION

Although prior studies of wound resealing in sinonasal epithelium have been limited, it has been demonstrated that certain soluble mediators have specific effects in augmenting or inhibiting wound closure.23,24 Based upon the importance of Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in certain types of inflammatory CRS, the experiments in this study were undertaken to determine the effects of these cytokines on sinonasal epithelial wound resealing in vitro. The results of these experiments are anticipated to lead to future clinical understanding of the mechanisms behind poor or delayed healing following paranasal sinus surgery.

Our experiments demonstrate reduced sinonasal epithelial wound resealing with exposure to Th2 cytokine IL-4, as hypothesized. At the completion of the timecourse wound closure studies, only 25% of IL-4 exposed wounds were completely closed, and the mean wound closure percentage for IL-4 exposed wounds was 85.02% ± 18.46%. Further, percentage closure of IL-4 exposed wounds differed from the media-only control at every post-wounding time point from 8 to 36 hours. These results indicate a substantial inhibitory effect of IL-4 exposure on sinonasal epithelial wound resealing. These results are, in part, similar to those seen in studies of human lung Calu-3 cell wound resealing, in which Th-2 cytokine exposure (IL-4 and IL-13) resulted in decreased epithelial migration.21

In contrast to the deleterious effect of IL-4 exposure on sinonasal epithelial wound resealing, IL-5 and IL-13 exposure groups did not differ significantly from the media-only control at any of the post-wounding time points in our experiments. Various possibilities may explain these results. First is the lack of a true effect on sinonasal epithelial wound resealing caused by IL-5 or IL-13. Although this is a small study, the wound closure percentage measurements appear fairly precise and reliable, without extensive variability across time points. Second, as only a single cytokine concentration was tested, the potential that the chosen concentration was not appropriate to inhibit sinonasal epithelial wound resealing in the IL-5 and IL-13 exposed groups should be considered. Prior studies of Th2 cytokine effects on sinonasal epithelial wound healing are not available for comparison. Although IL-5 and IL-13 exposure conditions have led to impaired wound healing in mouse models and lung cells in vitro, these results may not translate to sinonasal epithelial wound healing due to organ system and species differences.21,33 Future studies will better elucidate the precise role of IL-5 and IL-13 on sinonasal epithelial wound healing and either support or refute the findings in the current experiments.

Annexin A2 was reduced in actively healing IL-4 exposed wounds as identified by both immunofluorescence labeling pixel intensity analysis and Western immunoblot quantification. These reduced protein levels coincide with the decreased wound closure percentage seen under IL-4 exposure conditions. Whether IL-4 exposure has a direct effect on reduction of annexin A2 as the mechanism for impaired epithelial wound closure has not been fully evaluated in this study. However, this is a possibility and provides an interesting hypothesis for future investigations.

Certain limitations must be considered for this study. The first limitation is the use of a single cytokine concentration for each of the cytokine exposure conditions during sinonasal epithelial wound healing studies. Although the cytokine concentrations in these experiments were chosen based upon prior literature or laboratory experience, it is possible that varying the cytokine concentrations would have produced different effects in wound closure percentage across groups. Similar to the potential drawback of using a single cytokine concentration, it may be argued that limiting experimental exposure to a single cytokine in sinonasal epithelial wound resealing studies would also be a downfall. In the living human, there are innumerable cellular and soluble mediators that interact amongst each other and with surrounding cells. However, while the experimental conditions in this study do not precisely mimic the in vivo cytokine exposure during wound healing, separating the cytokine exposures to a single mediator allows controlled determination of the effects of one cytokine mediator, which is important for preliminary experiments. Once these individual effects are known, experiments may be expanded to assess cytokine interactions and their effects on sinonasal epithelial wound healing.

The second limitation of this study is the use of immunofluorescence labeling and confocal microscopy image pixel intensity analysis for quantification of sinonasal tissue protein levels. Although this technique has been previously used in similar studies, there is inherent variability in immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy image acquisition.34,35 In order to control this variability as much as possible, immunofluorescence labeling was performed and confocal images were acquired on the same day across cytokine exposure conditions. Further, confocal microscopy image acquisition settings were set to a single control sinonasal tissue specimen and retained across all images obtained. Like any scientific experiment or clinical trial, the limitations of the study must be considered in the context of the methods and results that are presented. This study has certain potential limitations, but nonetheless, presents interesting and novel results in a field that has been substantially understudied.

CONCLUSIONS

In a translational model of in vitro sinonasal epithelial wound resealing, Th2 cytokine IL-4 exposure results in reduced sinonasal epithelial wound closure over time and decreased total number of wounds closed compared with sinonasal tissues not exposed to IL-4. A consistent decrease in sinonasal epithelial expression of annexin A2 was also seen with IL-4 exposure during active wound resealing. These alterations in annexin A2 likely contribute to the impairment in sinonasal epithelial wound healing seen under IL-4 exposure conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Justin C. Wise, Ph.D. is kindly acknowledged for his assistance in experimental design and statistical analysis.

This work was supported in part by the following funding sources:

Clinical and Translational Science Award Program, National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources KL2 RR025009 and UL1 RR025008 (S.K.W.; Principal Investigator – David Stephens, M.D.) The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

American Rhinologic Society New Investigator Award (S.K.W.)

Short Term Training in Health Professional Schools, National Institutes of Health T35-HL007473 (K.A.D.; Principal Investigator – Robinna G. Lorentz, M.D, Ph.D.)

Structure function studies in intestinal epithelial JAM, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases DK061379 (C.A.P.)

Neutrophil interactions with intestinal epithelial cells, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, DK072564 (C.A.P.)

Intestinal epithelial tight junction structure-function, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, DK059888 (A.N.)

Footnotes

IRB Statement: The Institutional Review Board of Emory University granted approval for this study.

This manuscript and the data within it have not been previously published and are not under consideration for publication in any other journal.

| Author | Potential Conflicts of Interest |

|---|---|

| Sarah K. Wise, M.D., M.S.C.R. | None |

| Kyle A. Den Beste, B.S. | None |

| Elizabeth K. Hoddeson, M.D. | None |

| Charles Parkos, M.D, Ph.D | None |

| Asma Nusrat, M.D. | None |

REFERENCES

- 1.Soler ZM, Mace JC, Smith TL. Symptom-based presentation of chronic rhinosinusitis and symptom-specific outcomes after endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:297–301. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharyya N. Ambulatory sinus and nasal surgery in the United States: demographic and perioperative outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:635–638. doi: 10.1002/lary.20777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venkatraman G, Likosky DS, Zhou W, et al. Trends in endoscopic sinus surgery rates in the Medicare population. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:426–430. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albu S, Lucaciu R. Prophylactic antibiotics in endoscopic sinus surgery: a short follow-up study. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010;24:306–309. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2010.24.3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cote DW, Wright ED. Trimcinolone-impregnated nasal dressing following endoscopic sinus surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:1269–1273. doi: 10.1002/lary.20905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valentine R, Athanasiadis T, Moratti S, et al. The efficacy of a novel chitosan gel on hemostasis and wound healing after endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010;24:70–75. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2010.24.3422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorrisen M, Bachert C. Effect of corticoseroids on wound healing after sinus surgery. Rhinology. 2009;47:280–286. doi: 10.4193/Rhin08.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramadan HH, Hinerman RA. Smoke exposure and outcome of endoscopic sinus surgery in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:546–548. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.129816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HY, Dhong HJ, Chung SK, et al. Prognostic factors of pediatric endoscopic sinus surgery. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:1535–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atef A, Zeid IA, Qotb M, et al. Effects of passive smoking on ciliary regeneration of nasal mucosa after functional endoscopic sinus surgery in children. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:75–79. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108003678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riechelmann H, Deutschle T, Rozsasi A, et al. Nasal biomarker profiles in acute and chronic rhinosinusitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1186–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Zele T, Claeys S, Gavaert P, et al. Differentiation of chronic sinus diseases by measurement of inflammatory mediators. Allergy. 2006;61:1280–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li JY, Fang SY. Allergic profiles in unilateral nasal polyps of chronic bacterial rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:111–114. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan GK, Wang H, Takenaka H. Eosinophil infiltration and activation in nasal polyposis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:521–526. doi: 10.1080/00016480600951368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woodworth BA, Joseph K, Kaplan AP, et al. Alterations in eotaxin, monocyte chemoattractant protein-4, interleukin-5, and interleukin-13 after systemic steroid treatment for nasal polyps. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:585–589. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.al Ghamdi K, Ghaffar O, Small P, et al. IL-4 and IL-13 expression in chronic sinusitis: relationship with cellular infiltrate and effect of topical corticosteroid treatment. J Otolaryngol. 1997;26:160–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilos DL, Leung DYM, Wood R, et al. Evidence for distinct cytokine expression in allergic versus non-allergic chronic sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;95:537–544. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinke JW, Payne SC, Borish L. Interleukin-4 and the generation of the AERD phenotype: implications for molecular mechanisms driving therapeutic benefit of aspirin desensitization. J Allergy. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/182090. Epub 2012 January 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramanathan M, Lee WK, Spannhake EW, et al. Th2 cytokines associated with chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps down-regulate the antimicrobial immune function of human sinonasal epithelial cells. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:115–121. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borthwick LA, McIlroy EI, Gorowiec MR, et al. Inflammation and epithelial to mesenchymal transition in lung transplant recipients: role in dysregulated epithelial wound repair. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:496–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahdieh M, Vandenbos T, Youakim A. Lung epithelial barrier function and wound healing are decreased by IL-4 and IL-13 and enhanced by IFN-gamma. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C2029–C2038. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schäffer M, Weimer W, Wider S, et al. Differential expression of inflammatory mediators in radiation-impaired wound heaing. J Surg Res. 2002;107:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazard DS, Moore A, Hupertan V, et al. Muco-ciliary differentiation of nasal epithelial cells is decreased after wound healing in vitro. Allergy. 2009;64:1136–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan L, Hatzirodos N, Wormald P-J. Effect of nerve growth factor and keratinocyte growth factor on wound healing of the sinus mucosa. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:108–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babbin BA, Parkos CA, Mandell KJ, et al. Annexin A2 regulates intestinal epithelial cell spreading and wound closure through Rho-related signaling. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:951–966. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirshner J, Schumann D, Shively JE. CEACAM1, a cell-cell adhesion molecule, directly associates with annexin A2 in a three-dimensional model of mammary morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50338–50345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309115200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopkins A, Bruewer M, Brown G, et al. Epithelial cell spreading induced by hepatocyte growth factor influences paxillin protein synthesis and post-translational modification. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:886–898. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00065.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nusrat A, Parkos C, Liang T, et al. Neutrophil migration across model intestinal epithelia: monolayer disruption and subsequent events in epithelial repair. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1489–1500. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deakin N, Ballestrem C, Turner C. Paxillin and Hic-5 interaction with vinculin is differentially regulated by Rac1 and RhoA. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037990. Epub 2012 May 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lane AP, Saatian B, Yu XY, et al. mRNA for genes associated with antigen presentation are expressed by human middle meatal epithelial cells in culture. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1827–1832. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200410000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawker KM, Johnson PR, Hughes JM, et al. Interleuin-4 inhibits mitogen-induced proliferation of human airway smooth muscle cells in culture. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1998;275:L469–L477. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.3.L469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costa GG, Silva RM, Franco-Penteado CF, et al. Interactions between eotaxin and interleukin-5 in the chemotaxis of primed and non-primed human eosinophils. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;566:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leitch VD, Strudwick XL, Matthaei KI, et al. IL-5 overexpressing mice exhibit eosinophilia and altered wound healing through mechanisms involving prolonged inflammation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87:131–140. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zuckerman JD, Lee WY, DelGaudio JM, et al. Pathophysiology of nasal polyposis: the role of desmosomal junctions. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:589–597. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogers GA, Den Beste K, Parkos CA, et al. Epithelial tight junction alterations in nasal polyposis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1:50–54. doi: 10.1002/alr.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]