Abstract

Purpose

To examine the effects of clinically relevant pharmacological Notch inhibition on glioblastoma xenografts.

Experimental Design

Murine orthotopic xenografts generated from temozolomide sensitive and resistant glioblastoma neurosphere lines were treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor MRK003. Tumor growth was tracked by weekly imaging, and the effects on animal survival and tumor proliferation were assessed, along with the expression of Notch targets, stem cell and differentiation markers, and the biology of neurospheres isolated from previously treated xenografts and controls.

Results

Weekly MRK003 therapy resulted in significant reductions in growth as measured by imaging, as well as prolongation of survival. Microscopic examination confirmed a statistically significant reduction in cross-sectional tumor area and mitotic index in a MRK003-treated cohort as compared to controls. Expression of multiple Notch targets was reduced in the xenografts, along with neural stem/progenitor cell markers, while glial differentiation was induced. Neurospheres derived from MRK003-treated xenografts exhibited reduced clonogenicity and formed less aggressive secondary xenografts. Neurospheres isolated from treated xenografts remained sensitive to MRK003, suggesting that therapeutic resistance does not rapidly arise during in vivo Notch blockade.

Conclusions

Weekly oral delivery of MRK003 results in significant in vivo inhibition of Notch pathway activity, tumor growth, stem cell marker expression and clonogenicity, providing pre-clinical support for the use of such compounds in patients with malignant brain tumors. Some of these effects can persist for some time after in vivo therapy is complete.

Keywords: Glioblastoma, Cancer Stem Cell, γ-Secretase Inhibitor, Notch

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common primary malignancy of the central nervous system in adults, and more than 70% of patients die within 2 years of diagnosis (1). More effective therapies are urgently needed, including treatments which can target the subpopulation of primitive cancer stem cells (CSC) thought to be resistant to radiation and standard chemotherapies (2–4). It has been suggested that signaling pathways active in non-neoplastic neural stem cells are also required in stem-like glioma cells (5, 6), including Notch, a pathway also known to promote neural stem cell identity and survival in the fetal and adult brain (7–9).

Prior reports support the concept that Notch signaling is active in GBM and other malignant gliomas, and that Notch inhibition can slow the growth of tumor cells as well as sensitize them to radiation or chemotherapy (10–20). In many of these studies, in vitro Notch blockade resulted in reductions in clonogenic capacity or a decreased fraction of tumor cells expressing stem cell markers, suggesting that glioma CSCs have an ongoing requirement for pathway activity (13, 18, 19, 21, 22). The invasive capacity of gliomas has also been linked to Notch (23–25). Thus targeting Notch signaling may affect several processes critical for the growth and spread of GBM. Notch signaling can be initiated in gliomas by canonical and non-canonical pathway ligands, with hypoxia inducing their expression in neoplastic cells, and perivascular stromal cells serving as another potential source (22, 26, 27) (13, 19, 28). Alternative mechanisms, such as activation of Notch signaling by perivascular nitric oxide, have also been demonstrated (29).

Ligand binding to Notch induces cleavage of the transmembrane receptor by the γ-secretase complex, and several small molecule γ-secretase inhibitors (GSI) which block this process have been used to treat GBM cultures in vitro (13, 30–34). Much less is known, however, about the in vivo effects of GSIs on glioma stem cells and intracranial tumor growth.

We therefore used the GSI MRK003 to treat highly invasive, radiographically detectable orthotopic xenografts generated from GBM neurospheres (34). In a recent MK0572 GSI trial in patients with advanced solid tumors, a once weekly dosing scheme was found to be optimal (35). MRK003 is structurally similar to MK0572, and is used in preclinical in vivo studies of both solid tumors and leukemia as it has superior pharmacokinetic properties in rodents (36–41). The optimal MRK003 dosing regimen in mice is 300 mg/kg once weekly by oral gavage, with maximal plasma drug concentrations seen 4 hours after administration and trough levels after 72 hours (42). Similarly, MK0572 has been shown in humans to reach peak concentrations in 3 to 8.4 hours, with target engagement by the drug estimated to last 48 to 96 hours in a once per week dosing regimen (35).

We focused on whether the GSI could suppress Notch activity and the expression of stem cell markers in glioma cells in vivo, the effects on xenograft growth and clonogenic potential, and whether therapeutic resistance emerged in neurospheres isolated from treated tumors. Interestingly, we found that when neurospheres are isolated from xenografts previously treated with MRK003, they show reduced clonogenic capacity in vitro and generate less aggressive tumors in vivo in the absence of additional therapy. This suggests that in vivo Notch blockade can cause prolonged suppression of glioblastoma xenograft initiating capacity even after treatment has stopped.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and In Vitro Lentiviral Labeling

The HSR-GBM1 neurosphere line was isolated by Galli and colleagues from a primary GBM, and was originally designated 020913 (43). The same group later isolated GBM line 040821. Both lines lack mutations in IDH1, and show methylation of the MGMT promoter (data not shown). HSR-GBM1 lacks mutations in p53 exons 7 and 8, while 040821 cells have a mutation in exon 7 resulting in substitution of serine for proline in amino acid 278. The lines were maintained in culture as originally described, and their identities confirmed at least once each year using tandem repeat analysis.

Cells were counted using GUAVA Viacount reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Millipore, Billerica, MA). To facilitate imaging of the intracranial tumors, single cell suspensions of HSR-GBM1 or 040821 neurospheres were transduced with lentivirus (kindly provided by Dr. Gilson Baia) encoding a constitutively expressing luciferase gene (44). Five days after transduction, single cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 0.7 cell per well and individual colonies were obtained. The luciferase activity of every clone was measured using a luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) and expressed as relative luminescence units (RLU). Clones which had high RLU were designated HSR-GBM1-Luc or 040821-Luc and expanded for xenograft studies.

Intracranial Xenografts

105 HSR-GBM1-Luc or 040821-Luc cells in 2µl PBS dissociated to single cells were injected over 10 minutes into the right striatum of athymic (nu/nu) mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) as previously described (45). Mice were monitored daily for neurological changes, and tumor growth was tracked weekly using the Xenogen IVIS Spectrum optical imaging device and Living Image software (both from Caliperls, Hopkinton, MA). Tumors were first identified by imaging from 4 to 6 weeks after injection, and divided into vehicle and treatment groups containing lesions of comparable initial sizes. Animals in the treatment group received 300 mg/kg MRK003 provided by Merck Research Laboratories (Boston MA) once weekly by oral gavage prepared as previously described (46), while the control group received vehicle. After sacrifice, brains were removed and bisected in a coronal plane at the level of tumor injection. One half of the brain was formalin fixed, paraffin embedded and used for histopathological analysis. Visually apparent tumor in the other portion was used for nucleic acid extraction and the generation of secondary tumor neurospheres. Microscopic examination, including mitotic counts and quantification of Ki67 (sc15402, 1:250, Santa Cruz Biologicals, Santa Cruz, CA), PECAM (sc1506, 1:100, Santa Cruz Biologicals) and cleaved caspase 3 (#9661S, 1:25, Cell SignalingTechnology, Danvers, MA) was performed by a board-certified neuropathologist masked with respect to treatment group (B.A.O. or C.G.E.). Measurement of cross-sectional tumor area at the injection site was performed on the first H&E stained slide cut from each xenograft block by B.A.O., who was masked with respect to treatment group, using Spot Basic Software (SPOT Imaging Solutions, Sterling Heights, Michigan).

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Freshly dissected xenograft tissue was homogenized and nucleic acids extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA was further purified using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Reverse transcription and quantitative PCR were performed using ABI System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on an I-Cycler IQ Real-Time detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Expression levels were determined using the standard curve method with all expression levels being normalized to β-actin; all measurements were performed in triplicate. The following primers were used: human Hes1: forward (F) 5’-AGTGAAGCA-CCTCCGGAAC-3’, reverse (R) 5’-TCACCTCGTTCATGCACTC-3'; human Hes5: forward (F) 5’-CCGGTGGTGGAGAAGATC-3’, reverse (R) 5’-TAGTCCTGG- TGCAGGCTCTT-3’ ; human Hey1: forward (F) 5’-TCTGAGCTGAGAAGGCTGGT-3’, reverse (R) 5’-CGAAATCCCAAACTCCGATA-3’; human Hey2: forward (F) 5’-AGATGCTTCAGGCAACAGGG-3’, reverse (R) 5’-CAAGAGCGTGTGCGTCA-AAG-3'; human Nestin: forward (F) 5’-CCAGGAGCCACTGAAGACTC-3’, reverse (R) 5’-CCTTTCCCAGGTTCTCTTCC-3’; human CD133: forward (F) 5’-TCCACA-GAAATTTACCTACATTGG-3’, reverse (R) 5’-CAGCAGAGAGCAGATGACCA-3’; Human BMI1: forward (F) 5’-TGTCATGTATGAGGAGGAACCTT-3’, reverse (R) 5’-GTATTTCAATGGAAGTGGACCAT-3’; human Nanog: forward (F) 5’-CCTGTG-ATTTGTGGGCCTG-3’, reverse (R) 5’-GACAGTCTCCGTGTGAGGCAT-3’; human SOX2: forward (F) 5’-TTGCTG CCTCTTTAAGACTAGGA-3’, reverse (R) 5’-CTGGGGCTCAAACTTCTCTC-3’; human GFAP : forward (F) 5’-AACTGA-GGCACGAGCAAAGT-3’, reverse (R) 5’-GCAGTGCCCTGAAGATTAGC-3'; human MAP2: forward (F) 5’-CCATCTTGGTGCCGAGTGAG-3’, reverse (R) 5’-TGGGAGTCGCAGGAGATTTTG-3'; and human β-actin: forward (F) 5’-CCCAGC-ACAATGAAGATCAA-3’, reverse (R) 5’-GATCCACACGGAGTACTTG-3’ (28, 31).

Primary Culture Derived from Intracranial Xenograft Tumors and Drug Treatment Assays

Tumor neurospheres were isolated from murine xenografts in as described for human specimens (43). After 7 to 10 days, new spheres that could undergo further passaging were formed. For drug treatment assays, viable cells were plated at 2500 cells/well in a 96-well plate containing serum-free neurosphere media, and treated with indicated levels of MRK003. Viable cell biomass was measured 96 hours later using CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI).

Clonogenic Assays

Clonogenic assays were performed as previously described (28), with passage two neurospheres derived from xenografts triturated into a single cell suspension and 104 cells/5ml seeded per well. At least three separate wells were analyzed per culture. Colonies were measured and counted after 3 weeks, using Motic Images Plus (Motic, Richmond, Canada).

Statistical Methods

Unless otherwise noted, in vitro and quantitative PCR data are shown as mean values with error bars representing standard deviation (SD) for at a minimum three replicates, and experiments were repeated at least once. Comparison of mean values between groups was evaluated by unpaired, two-tailed t test. Log rank analysis of Kaplan-Meier curves was used to evaluate the survival. For all statistical methods, a P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. All tests were performed by using GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Oral GSI slows intracranial glioblastoma xenografts growth and prolongs survival

Intracranial tumor xenografts were initiated using glioblastoma-derived neurosphere lines previously shown to form infiltrative malignant gliomas in nude mice (13, 28, 43, 45). We chose representative temozolomide sensitive and resistant neurosphere cultures for these studies. Growth of HSR-GBM1 cells was not inhibited by up to 150 µM concentrations of temozolomide, while the 040821 line showed a profound dose-dependent reduction in growth (Fig.1).

Fig. 1. Temozolomide sensitivity of glioblastoma neurospheres.

A, The growth of HSR-GBM1 cells was not inhibited by up to 150 µM concentrations of temozolomide. B–C, In contrast, the 040821 line showed dose-dependent sensitivity to temozolomide.

Both tumor growth and overall survival were used as endpoints in our initial analyses. In order to generate equivalent treatment groups and facilitate tracking of xenograft growth, cultures were transduced with a luciferase reporter (44). Mice were imaged weekly starting four weeks after the injection, and when HSR-GBM1 tumors were detected mice were randomized into treatment and control groups of 10 and 9 animals with equal mean initial tumor sizes. Treatment began the next day, with 300mg/kg MRK003 once weekly by oral gavage. Mouse body weight was monitored weekly, and no significant weight loss was noted in the GSI treated animals as compared to controls until they became symptomatic due to increased tumor burden, suggesting that weekly administration of the GSI was well tolerated.

Weekly imaging revealed growth in both the control and MRK003 treatment groups (Fig. 2A). However, xenografts in the GSI treated group had a 49% slower growth rate than matched controls (p<0.005; Fig. 2B). Overall survival from the point treatment was initiated was also significantly longer in animals receiving weekly MRK003 (p<0.05, Fig. 2B). Xenografts initiated using 040821 GBM neurospheres, also showed a significant decrease in growth over 5 weeks measured using luciferase-based imaging ( p<0.05, Fig. 2C,D) as well as prolonged overall survival (p<0.05, Fig. 2C,D) with MRK003 treatment. Thus weekly GSI therapy can slow the intracranial growth of both temozolomide sensitive and temozolomide resistant GBM neurosphere lines and prolong animal survival.

Fig. 2. MRK003 slows growth of glioblastoma xenografts and prolongs survival.

A, Animals with HSR-GMB1 xenografts were separated into treatment and control groups when luciferase-expressing tumors were first detected (designated W0), and weekly oral treatment with MRK003 or vehicle was initiated at this point. Tumors were imaged for the next 5 weeks, and animals sacrificed when they became symptomatic (HSR-GMB1 XG1 trial). B, Mean tumor growth as measured by luciferase imaging was 49% slower in animals treated with oral MRK003 than in controls (left panel, p<0.005). GSI-treated mice have significantly prolonged survival (median survival: 35 days vs. 29 days from initiation of treatment, log-rank test p<0.05). C, Mean 040821 tumor xenograft growth as measured by luciferase imaging was 62% slower in animals treated with oral MRK003 than in controls (left panel, p<0.05; 040821 XG1 trial). MRK003-treated mice had significantly longer survival compared with vehicle-treated animals. (median survival: 40 days vs. 28 days from initiation of treatment, log-rank test: p<0.05).

Microscopic analysis of GBM xenografts following Notch blockade

We performed another in vivo study in which tumors were examined after the same treatment interval in order to facilitate direct comparison between treated and control lesions. Mice bearing HSR-GBM1 xenografts were randomized after tumor detection and given five weekly treatments with MRK003 or vehicle and then sacrificed 16 hours after the last oral dose. As before, weekly imaging of animals in the control and MRK003 treatment groups revealed that xenografts in the mice receiving the GSI grew significantly more slowly than matched controls (p<0.05; Fig. S1).

Brains were removed for microscopic and molecular analysis, and GBM neurospheres were isolated from the xenografts so their functional properties could be assessed (Fig. 3A). A coronal cut was made through the injection site, and the microscopic cross-sectional area of each tumor was measured on a H&E stained slide at this level (Fig. 3B). Consistent with the luciferase-based growth measurements, microscopic analysis revealed that xenografts in MRK003-treated mice had a mean 76% smaller tumor area at the level of injection than those in the vehicle treated group (p<0.05, Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Microscopic and molecular analysis of glioblastoma xenografts following Notch blockade.

A, In this HSR-GBM1 XG2 trial, brains were removed 16 hours after the last of five weekly treatments and sectioned through the injection site. One portion of the brain was processed for microscopic analysis, while the other was used for mRNA extraction and xenograft-derived neurosphere culture. These neurospheres were used for GSI resistance assays, clonogenic assays and secondary xenograft injection. B, Microscopic evaluation confirmed the presence of infiltrating gliomas in all animals (original magnification 2X), with cross-sectional area at the level of injection 76% lower in the MRK003 treated cohort (p<0.05). C, Numerous mitotic figures were identified in both treated and control tumors, with a few representative mitotic profiles highlighted by arrows (original magnification 200×). A 56% reduction in mean mitotic index was noted in MRK003 treated mice as compared to controls (p<0.05).

Microscopic analysis failed to highlight any pronounced difference in glioma cell morphology following treatment, but a mean 56% reduction in mitotic index was identified in the MRK003 treated mice (p<0.05; Fig. 3C). Immunohistochemical analysis showed a 18% decreased in the Ki67 proliferation index in MRK003 treated tumors, but the difference was not statistically significant (data not shown). No regions of tumor necrosis were identified, and cleaved caspase-3 immunohistochemistry revealed a high apoptotic rate in all tumors with no significant difference between the treatment and control groups in two separate analyses (data not shown).

Finally, because Notch has been implicated in the control of angiogenesis and vascular density, we examined the number of PECAM1(CD31) immunopositive vessels in the xenografts. An increase of 42% was observed in the number of vessels in MRK003 treated cohort, but this trend was not statistically significant (p = 0.08; Fig. S2A). We also measured expression of the pro-angiogenic factor VEGF in RNA extracted from the xenografts using quantitative PCR and human-specific primers so that only tumor-derived mRNA was analyzed. Again, however, the VEGF increase seen in tumors treated with MRK003 was not significant (Fig. S2B). Nevertheless, our data are congruent with recent publications by several groups suggesting that GSI treatment leads to VEGF-driven aberrant growth of tumor blood vessels (47, 48).

Oral GSI inhibits Notch pathway activity and expression of stem cell markers

In order to confirm that oral GSI can penetrate the brain and block Notch signaling, we measured expression of established pathway targets in tumor-derived mRNA in all three xenograft cohorts. This included the HSR-GBM1 survival trial “XG1” with 9 vehicle and 10 MRK003 treated animals, the HSR-GBM1 “XG2” cohort in which animals were treated with vehicle (n=5) or MRK003 (n=7) for equal lengths of time, and the 040821 XG1 survival cohort comprising 7 vehicle and 7 MRK003 treated mice. Tumors in all of these MRK003-treated groups had significant 47% to 75% reductions in the mRNA levels of the Notch target Hes5 (Fig. 4A). Statistically significant reductions of 30% or more were seen in the target Hes1 in the HSR-GBM1 XG1 and 040821 XG1 groups. Finally, the MRK003-treated HSR-GBM1 XG1 and XG2 tumors showed significant reductions in Hey1 of 37% and 66% respectively. In contrast, Hey2 did not respond significantly to GSI treatment in any trial. Thus orally delivered MRK003 inhibits the Notch pathway in intracranial glioma xenografts, and the bulk of tumor cells do not become refractory to pathway blockade over five or more weeks of in vivo treatment.

Fig. 4. Oral MRK003 treatment affects proliferation and expression of Notch targets and neural stem cell and differentiation markers in glioblastoma xenografts.

For each of the four xenograft experiments, mRNA was extracted from a portion of the tumor and examined by quantitative PCR with human specific primers. XG1 animals were sacrificed when they became symptomatic, which occurred at varying time points after their last treatment. In the XG2 trial, all animals were sacrificed 16 hours after the last treatment. In the XG3 trial, no treatments were given. A, The Notch targets Hes1, Hes5 and Hey1 had their mRNA levels significantly reduced in most MRK003-treated cohorts, while Hey2 did not respond to the GSI. B, mRNA levels of neural stem/progenitor markers were also reduced in MRK003 treated xenografts. C, The glial and neuronal differentiation markers GFAP and MAP2 increased following Notch blockade, but decreased in the untreated HSR-GBM1 XG3 xenografts generated from neurospheres isolated from MRK003-treated tumors.

We and others have previously shown that in vitro pharmacological blockade of Notch signaling can deplete stem-like GBM cells (13, 14, 18, 31, 49). To test the in vivo requirement for Notch in glioma stem cells, we measured mRNA levels for stem/progenitor, glial and neuronal markers in the same groups described above. The mean mRNA levels of most stem cell markers were lowered in the treated xenografts, although because expression of stem cell markers in the vehicle treated cohorts varied quite a bit many of these reductions did not reach the level of statistical significance. Nanog levels showed significant 42% to 75% reductions in all three MRK003-treated cohorts, nestin levels significant 36% to 43% reductions in two of three, and CD133 a significant 46% reduction in one (Fig. 4B). Finally, mean mRNA levels of glial (GFAP) and neuronal (MAP2) differentiation markers showed significant GFAP increases of 165% to 201% in the two HSR-GBM1 studies, and a significant 28% increase of the neuronal marker MAP2 in 040821 XG1 xenografts following Notch blockade (Fig. 4C). These findings suggest that oral GSI inhibits the expression of stem cell markers, and induces glial differentiation in glioblastoma xenografts.

Prolonged suppression of clonogenicity and in vivo growth capacity following Notch blockade in xenografts

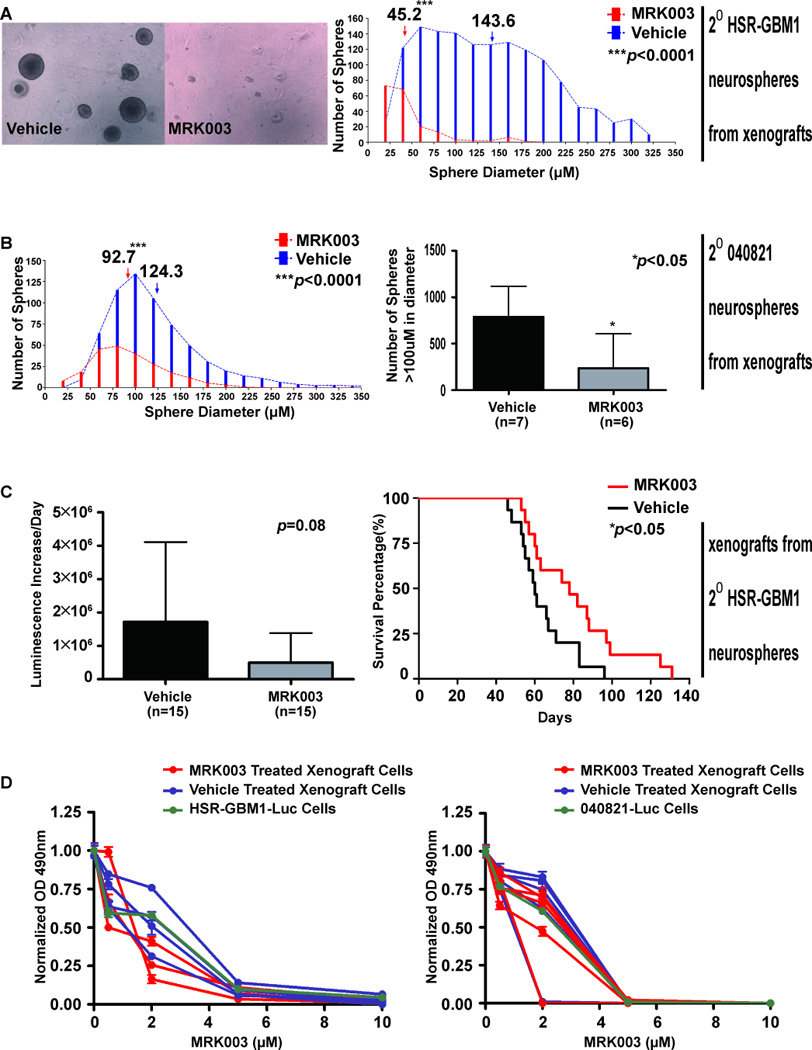

We cultured neurospheres from the xenografts, propagating them with no in vitro GSI therapy. Consistent with the concept that in vivo Notch blockade had depleted stem-like cells required for long term tumor growth, neurospheres could only be propagated from 3 of 7 MRK003 XG2 treated tumors as compared to 4 of 5 vehicle treated ones. To further investigate growth potential of neurospheres derived from treated and untreated xenografts, we performed clonogenic assays in all these re-isolated neurosphere lines at the second passage. Interestingly, even after two passages in media without any GSI added, neurospheres derived from MRK003-treated xenografts exhibited a significant reduction in clonogenic potential as compared to vehicle treated ones (Fig. 5A, p<0.0001, analysis of combined data from triplicate studies for each of the 7 xenograft-derived lines). Mean neurosphere size was reduced from 144µm to 45µm in cells previously treated with MRK003 (Fig. 5A). We have previously shown that only spheres over 100 micrometers can be serially passaged (28), suggesting that smaller ones are not derived from true stem cells.

Fig. 5. Persistent reduction in clonogenic capacity and in vivo tumor growth, but no induction of GSI resistance, following MRK003 treatment of xenografts.

A, Neurospheres derived from HSR-GBM1 XG2 MRK003-treated xenografts formed colonies in methycellulose that were significantly smaller and less numerous than those derived from vehicle-treated tumors. Average neurosphere size shifted from 144 µm to less than 50 µm (p<0.0001), and the number of spheres over 100 µm in size was reduced 98% (p<0.0001). B, Similarly, neurospheres derived from MRK003 treated 040821 XG1 showed significant decreases in the mean size and the number of large spheres. C, HSR-GBM1 XG2 derived neurospheres were also injected into nu/nu mice and allowed to form XG3 xenografts with no further therapy. Mean tumor growth as measured by luciferase imaging was 71% slower in animals with xenografts generated from spheres isolated from previously MRK003-treated mice, but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.08). However, tumors initiated from neurospheres derived from previously MRK003-treated animals resulted in significantly prolonged survival (median survival 78 days vs. 60 days, log-rank test: p<0.05). D, Growth over 96 hours in culture in the presence of increasing levels of MRK003 was measured in parental neurospheres or those derived from HSR-GBM` XG2 and 040821 XG1 xenografts. GBM neurospheres derived from tumors treated in vivo did not show any increase in resistance to repeat Notch blockade in vitro.

To rule out the possibility that limited clonogenicity of secondary spheres was due to lingering effects on cell cycle, we examined the distribution of cells in G0/G1, S phase, and G2/M using flow cytometry, with essentially identical results in spheres from MRK003 and vehicle treated xenografts (Fig. S3A). Differing degrees of contamination from murine cells could also potentially affect functional analyses, but immunostaining of neurospheres derived from MRK003 and vehicle treated xenografts performed alongside parental cells using a human specific antibody did not show a significant number of murine cells in the cultures (Fig. S3B).

We also examined clonogenic potential in neurospheres derived from 040821 xenografts, with all 7 vehicle and 6 of 7 MRK003 treated tumors giving rise to cultures. The mean neurosphere size was decreased from 124µm to 93µm by prior in vivo Notch blockade, with approximately four times as many large (>100µm) spheres arising from vehicle treated xenografts (Fig. 5B, p<0.05). Our studies analyzing neurospheres derived from treated and untreated xenografts thus reveal a persistent suppression of clonogenicity, which may be mediated by effects on stem-like cells.

In order to confirm durable alterations affecting the initiation and/or propagation of tumors following in vivo Notch blockade, we expanded passage 2 neurospheres derived from treated and untreated HSR-GBM1 tumors and injected equal numbers of viable cells into the brains of nu/nu mice, then tracked their growth with no additional therapy. Three lines derived from MRK003-treated xenografts and three from vehicle treated xenografts were injected into 5 animals each, and the two resulting cohorts of 15 animals were followed by weekly luminescence imaging and sacrificed when they became symptomatic. The growth of xenografts derived from tumors previously treated with MRK003 was slower than controls, although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.08, Fig. 5C). However, a significant prolongation in survival was seen among the cohort generated with cells previously treated with MRK003 (p< 0.05, Fig. 5C). We analyzed expression of Notch targets and stem and differentiation markers in these secondary HSR-GBM1 “XG3” xenografts, and found that markers of Notch activity (Hes1, Hes5, Hey1) remained suppressed in the absence of ongoing therapy (Fig 4A). The stem cell markers CD133 and SOX2 also were significantly lower (Fig. 4B), but interestingly the differentiation factors GFAP showed a significant change opposite that seen in the prior round of xenografts (Fig. 4C).

GBM neurospheres derived from xenografts previously treated with MRK003 remain sensitive to GSI

Hedgehog pathway blockade can rapidly result in the emergence of resistant tumor cells (50, 51). To determine if in vivo Notch blockade also efficiently promotes resistance we treated the cultured neurospheres derived from both treated and untreated tumors, as well as parental cells, with different concentration of MRK003 for 96 hours in vitro and measured viable cell mass. Neurospheres from MRK003-treated HSR-GBM1 and 040821 xenografts remained sensitive to MRK003 in vitro, suggesting that the period of in vivo therapy had not resulted in broad resistance to Notch inhibition (Fig. 5D).

Discussion

Notch signaling is important for the initiation and growth of a wide range of tumors (52–55), and a number of small molecule inhibitors of the γ-secretase complex have been developed to target this pathway. One challenge has been ameliorating the gastrointestinal side effects of Notch inhibition, which results in goblet cell metaplasia (56, 57). Two recently published phase I trials of the GSIs RO4929097 and MK0752 in patients with advanced solid malignancies tested a range of dosing schedules, in the hopes that intermittent pathway blockade would show more manageable toxicities .(35, 58).

In the MK0752 trial, a once per week dosing regimen was associated with notably less GI toxicity and fatigue (35). Interestingly, while patients with 18 different types of solid neoplasms were treated, most of which were from outside the brain, clinical activity was essentially restricted to intracranial gliomas of various types. This highlights the potential of Notch inhibitors as novel therapies for gliomas, and the need to better understand their mechanisms of action using clinically relevant in vivo models and dosing schedules.

Our goals were to determine if weekly oral administration of the GSI MRK003 could effectively inhibit Notch signaling in orthotopic glioblastoma xenografts, and to examine its effects on tumor growth and clonogenic potential. Weekly oral administration of MRK003 was effective in inhibiting the growth of xenografts generated from both temozolomide sensitive and resistant neurosphere lines as measured by serial imaging. Survival was also significantly longer in treated animals, consistent with the recent report of biological response in some glioma patients (35).

In addition to these studies using survival as an endpoint, we examined another cohort treated for equivalent periods of time with MRK003 or vehicle. In these xenografts, MRK003 treatment was associated with a significantly lower mitotic rate and smaller cross-sectional area. Quantitative PCR analysis of all the xenograft trials showed decreased expression of a number of Notch targets, indicating that the small molecule pathway inhibitor is able to effectively penetrate the brain and block pathway activity. The levels of several stem cell markers were also decreased, suggesting a potential effect on cancer stem cells.

Functional analyses using tissue harvested from treated and untreated xenografts support the notion that in vivo Notch inhibition depletes clonogenic capacity. Neurospheres were more difficult to isolate from tumors treated with MRK003 than controls, and reduced clonogenicity persisted over several passages. We found that the size and number of both HSR-GBM1 and 040821 tumor spheres remained significantly lower two passages after they had been isolated from xenografts, with no ongoing therapy in culture. Further proof of the durable suppression of tumor growth capacity came when we re-injected equal numbers of HSR-GBM1 cells isolated from MRK003 or vehicle treated xenografts back into the brains of nu/nu mice. Despite the lack of any treatment of the in vitro cultures or secondary xenografts, prior anti-Notch therapy was associated with significant prolongation of survival. These secondary xenograft assays support our previously published in vitro clonogenic results, and suggest that in vivo Notch inhibition can have effects on tumor initiation and growth that persist for a period of time after treatment. The suppression of stem-cell markers suggests that this could be due at least in part to depletion of a stem-like cells from tumors, although other mechanisms are also possible, such as variation of stem cell marker expression in conjunction with proliferation changes.

Encouragingly, broad resistance to the GSI did not emerge following in vivo therapy, as neurospheres isolated from treated xenografts remained sensitive to MRK003. However, it seems likely that GSI therapy will need to be combined with other treatments if long term survival of glioblastoma patients is to be achieved. It has been suggested that Notch inhibition in conjunction with temozolomide chemotherapy (14, 15, 17, 18)) or radiation (59)60 can more effectively treat malignant gliomas than these standard therapies alone. We have also previously suggested based on in vitro studies that targeting both Notch and Hedgehog simultaneously may increase therapeutic efficacy (31).

In summary, oral delivery of the GSI MRK003 results in significant inhibition of Notch pathway activity in intracranial xenografts generated from GBM neurospheres, and can slow the growth of both temozolomide sensitive and resistant malignant gliomas. Treatment was associated with suppression of stem cell markers and induction of differentiation markers in tumor xenografts, as well as reduced mitotic activity. Interestingly, a persistent reduction in clonogenic and in vivo tumor growth capacity was noted after xenograft treatment was stopped, suggesting that Notch blockade can have prolonged effects on glioma biology.

Supplementary Material

Translational Significance.

Glioblastoma are among the most aggressive solid tumors, and essentially no curative therapies currently exist. The Notch pathway represents an attractive new target, but testing of clinically relevant glioma models and therapeutic regimens has been limited. We report that orally delivered γ-secretase inhibitor MRK003 can effectively penetrate the brain and inhibit Notch activity, stem cell phenotype and tumor growth in xenografts generated from glioblastoma neurospheres. Interestingly, neurospheres isolated from MRK003-treated xenografts show persistent suppression of clonogenicity and in vivo growth capacity, suggesting than Notch blockade can have long-term effects on glioma biology.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Dr. Eberhart was supported by the James S. McDonnell Foundation / Brain Tumor Funders Collaborative and the National Institutes of Health (Grant #NS055089). Dr. Orr was supported in part by an NIH postdoctoral fellowship (T32CA067751). Dr. Chu received partial fellowship support from Merck.

We thank members of the Dr. Eberhart laboratory for helpful discussions, Ms. Ann Price for performing immunohistochemical stains and other technical assistance, Weijie Poh for performing methylation specific PCR for MGMT on neurosphere lines, and Dr. Angelo Vescovi and Dr. Francesco Di Meco for their kind gift of HSR-GBM1 and 040821 cells. We thank Merck and its scientists for providing MRK003 and information on in vivo dosing regimens.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of interest: C.G. Eberhart discloses a patent licensed to Stemline Therapeutics. No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed by other authors.

References

- 1.Preusser M, de Ribaupierre S, Wohrer A, Erridge SC, Hegi M, Weller M, et al. Current concepts and management of glioblastoma. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:9–21. doi: 10.1002/ana.22425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonavia R, Inda MM, Cavenee WK, Furnari FB. Heterogeneity maintenance in glioblastoma: a social network. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4055–4060. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lathia JD, Heddleston JM, Venere M, Rich JN. Deadly teamwork: neural cancer stem cells and the tumor microenvironment. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:482–485. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sul J, Fine HA. Malignant gliomas: new translational therapies. Mt Sinai J Med. 2010;77:655–666. doi: 10.1002/msj.20223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westphal M, Lamszus K. The neurobiology of gliomas: from cell biology to the development of therapeutic approaches. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:495–508. doi: 10.1038/nrn3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Read TA, Hegedus B, Wechsler-Reya R, Gutmann DH. The neurobiology of neurooncology. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:3–11. doi: 10.1002/ana.20912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierfelice TJ, Schreck KC, Eberhart CG, Gaiano N. Notch, neural stem cells, and brain tumors. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:367–375. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lino MM, Merlo A, Boulay JL. Notch signaling in glioblastoma: a developmental drug target? BMC Med. 2010;8:72. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stockhausen MT, Kristoffersen K, Poulsen HS. The functional role of Notch signaling in human gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:199–211. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purow BW, Haque RM, Noel MW, Su Q, Burdick MJ, Lee J, et al. Expression of Notch-1 and its ligands, Delta-like-1 and Jagged-1, is critical for glioma cell survival and proliferation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2353–2363. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shih AH, Holland EC. Notch signaling enhances nestin expression in gliomas. Neoplasia. 2006;8:1072–1082. doi: 10.1593/neo.06526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanamori M, Kawaguchi T, Nigro JM, Feuerstein BG, Berger MS, Miele L, et al. Contribution of Notch signaling activation to human glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:417–427. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan X, Khaki L, Zhu TS, Soules ME, Talsma CE, Gul N, et al. NOTCH pathway blockade depletes CD133-positive glioblastoma cells and inhibits growth of tumor neurospheres and xenografts. Stem Cells. 2010;28:5–16. doi: 10.1002/stem.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Wakeman TP, Lathia JD, Hjelmeland AB, Wang XF, White RR, et al. Notch promotes radioresistance of glioma stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:17–28. doi: 10.1002/stem.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbert CA, Daou MC, Moser RP, Ross AH. Gamma-secretase inhibitors enhance temozolomide treatment of human gliomas by inhibiting neurosphere repopulation and xenograft recurrence. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6870–6879. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Kesari S, Rooney C, Strack PR, Shen H, Wu L, et al. Inhibition of notch signaling blocks growth of glioblastoma cell lines and tumor neurospheres. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:822–835. doi: 10.1177/1947601910383564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hovinga KE, Shimizu F, Wang R, Panagiotakos G, Van Der Heijden M, Moayedpardazi H, et al. Inhibition of notch signaling in glioblastoma targets cancer stem cells via an endothelial cell intermediate. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1019–1029. doi: 10.1002/stem.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulasov IV, Nandi S, Dey M, Sonabend AM, Lesniak MS. Inhibition of Sonic hedgehog and Notch pathways enhances sensitivity of CD133(+) glioma stem cells to temozolomide therapy. Mol Med. 2011;17:103–112. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiang L, Wu T, Zhang HW, Lu N, Hu R, Wang YJ, et al. HIF-1alpha is critical for hypoxia-mediated maintenance of glioblastoma stem cells by activating Notch signaling pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:284–294. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Wang C, Meng Q, Li S, Sun X, Bo Y, et al. siRNA targeting Notch-1 decreases glioma stem cell proliferation and tumor growth. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:2497–2503. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhen Y, Zhao S, Li Q, Li Y, Kawamoto K. Arsenic trioxide-mediated Notch pathway inhibition depletes the cancer stem-like cell population in gliomas. Cancer Lett. 2010;292:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu TS, Costello MA, Talsma CE, Flack CG, Crowley JG, Hamm LL, et al. Endothelial cells create a stem cell niche in glioblastoma by providing NOTCH ligands that nurture self-renewal of cancer stem-like cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6061–6072. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sivasankaran B, Degen M, Ghaffari A, Hegi ME, Hamou MF, Ionescu MC, et al. Tenascin-C is a novel RBPJkappa-induced target gene for Notch signaling in gliomas. Cancer Res. 2009;69:458–465. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Chen T, Zhang J, Mao Q, Li S, Xiong W, et al. Notch1 promotes glioma cell migration and invasion by stimulating beta-catenin and NF-kappaB signaling via AKT activation. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raghu H, Gondi CS, Dinh DH, Gujrati M, Rao JS. Specific knockdown of uPA/uPAR attenuates invasion in glioblastoma cells and xenografts by inhibition of cleavage and trafficking of Notch-1 receptor. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:130. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seidel S, Garvalov BK, Wirta V, von Stechow L, Schanzer A, Meletis K, et al. A hypoxic niche regulates glioblastoma stem cells through hypoxia inducible factor 2 alpha. Brain. 2010;133:983–995. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun P, Xia S, Lal B, Eberhart CG, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Maciaczyk J, et al. DNER, an epigenetically modulated gene, regulates glioblastoma-derived neurosphere cell differentiation and tumor propagation. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1473–1486. doi: 10.1002/stem.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bar EE, Lin A, Mahairaki V, Matsui W, Eberhart CG. Hypoxia increases the expression of stem-cell markers and promotes clonogenicity in glioblastoma neurospheres. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1491–1502. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charles N, Ozawa T, Squatrito M, Bleau AM, Brennan CW, Hambardzumyan D, et al. Perivascular nitric oxide activates notch signaling and promotes stem-like character in PDGF-induced glioma cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan X, Matsui W, Khaki L, Stearns D, Chun J, Li YM, et al. Notch pathway inhibition depletes stem-like cells and blocks engraftment in embryonal brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7445–7452. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schreck KC, Taylor P, Marchionni L, Gopalakrishnan V, Bar EE, Gaiano N, et al. The Notch target Hes1 directly modulates Gli1 expression and Hedgehog signaling: a potential mechanism of therapeutic resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6060–6070. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolb EA, Gorlick R, Keir ST, Maris JM, Lock R, Carol H, et al. Initial testing (stage 1) by the pediatric preclinical testing program of RO4929097, a gamma-secretase inhibitor targeting notch signaling. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:815–818. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao SS, O'Neil J, Liberator CD, Hardwick JS, Dai X, Zhang T, et al. Inhibition of NOTCH signaling by gamma secretase inhibitor engages the RB pathway and elicits cell cycle exit in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3060–3068. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J, Kotliarova S, Kotliarov Y, Li A, Su Q, Donin NM, et al. Tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas cultured in bFGF and EGF more closely mirror the phenotype and genotype of primary tumors than do serum-cultured cell lines. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krop I, Demuth T, Guthrie T, Wen PY, Mason WP, Chinnaiyan P, et al. Phase I pharmacologic and pharmacodynamic study of the gamma secretase (Notch) inhibitor MK-0752 in adult patients with advanced solid tumors. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:2307–2313. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook N, Frese KK, Bapiro TE, Jacobetz MA, Gopinathan A, Miller JL, et al. Gamma secretase inhibition promotes hypoxic necrosis in mouse pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Exp Med. 2012;209:437–444. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Efferson CL, Winkelmann CT, Ware C, Sullivan T, Giampaoli S, Tammam J, et al. Downregulation of Notch pathway by a gamma-secretase inhibitor attenuates AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling and glucose uptake in an ERBB2 transgenic breast cancer model. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2476–2484. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pandya K, Meeke K, Clementz AG, Rogowski A, Roberts J, Miele L, et al. Targeting both Notch and ErbB-2 signalling pathways is required for prevention of ErbB-2-positive breast tumour recurrence. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:796–806. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kondratyev M, Kreso A, Hallett RM, Girgis-Gabardo A, Barcelon ME, Ilieva D, et al. Gamma-secretase inhibitors target tumor-initiating cells in a mouse model of ERBB2 breast cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31:93–103. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cullion K, Draheim KM, Hermance N, Tammam J, Sharma VM, Ware C, et al. Targeting the Notch1 and mTOR pathways in a mouse T-ALL model. Blood. 2009;113:6172–6181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-136762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Konishi J, Kawaguchi KS, Vo H, Haruki N, Gonzalez A, Carbone DP, et al. Gamma-secretase inhibitor prevents Notch3 activation and reduces proliferation in human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8051–8057. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watters JW, Cheng C, Majumder PK, Wang R, Yalavarthi S, Meeske C, et al. De novo discovery of a gamma-secretase inhibitor response signature using a novel in vivo breast tumor model. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8949–8957. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galli R, Binda E, Orfanelli U, Cipelletti B, Gritti A, De Vitis S, et al. Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem-like neural precursors from human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7011–7021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dinca EB, Sarkaria JN, Schroeder MA, Carlson BL, Voicu R, Gupta N, et al. Bioluminescence monitoring of intracranial glioblastoma xenograft: response to primary and salvage temozolomide therapy. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:610–616. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/09/0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bar EE, Chaudhry A, Lin A, Fan X, Schreck K, Matsui W, et al. Cyclopamine-mediated hedgehog pathway inhibition depletes stem-like cancer cells in glioblastoma. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2524–2533. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis HD, Leveridge M, Strack PR, Haldon CD, O'Neil J, Kim H, et al. Apoptosis in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells after cell cycle arrest induced by pharmacological inhibition of notch signaling. Chem Biol. 2007;14:209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalen M, Heikura T, Karvinen H, Nitzsche A, Weber H, Esser N, et al. Gamma-secretase inhibitor treatment promotes VEGF-A-driven blood vessel growth and vascular leakage but disrupts neovascular perfusion. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Masuda S, Kumano K, Suzuki T, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T, Natsugari H, et al. Dual antitumor mechanisms of Notch signaling inhibitor in a T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia xenograft model. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:2444–2450. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu YY, Zheng MH, Cheng G, Li L, Liang L, Gao F, et al. Notch signaling contributes to the maintenance of both normal neural stem cells and patient-derived glioma stem cells. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yauch RL, Dijkgraaf GJ, Alicke B, Januario T, Ahn CP, Holcomb T, et al. Smoothened mutation confers resistance to a Hedgehog pathway inhibitor in medulloblastoma. Science. 2009;326:572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1179386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rudin CM, Hann CL, Laterra J, Yauch RL, Callahan CA, Fu L, et al. Treatment of medulloblastoma with hedgehog pathway inhibitor GDC-0449. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1173–1178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang J, Sullenger BA, Rich JN. Notch signaling in cancer stem cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;727:174–185. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0899-4_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lobry C, Oh P, Aifantis I. Oncogenic and tumor suppressor functions of Notch in cancer: it's NOTCH what you think. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1931–1935. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ranganathan P, Weaver KL, Capobianco AJ. Notch signalling in solid tumours: a little bit of everything but not all the time. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:338–351. doi: 10.1038/nrc3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Targeting the Notch Pathway: Twists and Turns on the Road to Rational Therapeutics. J Clin Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong GT, Manfra D, Poulet FM, Zhang Q, Josien H, Bara T, et al. Chronic treatment with the gamma-secretase inhibitor LY-411,575 inhibits beta-amyloid peptide production and alters lymphopoiesis and intestinal cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12876–12882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Es JH, van Gijn ME, Riccio O, van den Born M, Vooijs M, Begthel H, et al. Notch/gamma-secretase inhibition turns proliferative cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas into goblet cells. Nature. 2005;435:959–963. doi: 10.1038/nature03659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tolcher AW, Messersmith WA, Mikulski SM, Papadopoulos KP, Kwak EL, Gibbon DG, et al. Phase I study of RO4929097, a gamma secretase inhibitor of Notch signaling, in patients with refractory metastatic or locally advanced solid tumors. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:2348–2353. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin J, Zhang XM, Yang JC, Ye YB, Luo SQ. gamma-secretase inhibitor-I enhances radiosensitivity of glioblastoma cell lines by depleting CD133+ tumor cells. Arch Med Res. 2010;41:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.