Abstract

Expansion of the tourism industry in the Dominican Republic has had far-reaching health consequences for the local population. Research suggests families with one or more members living in tourism areas experience heightened vulnerability to HIV/STIs due to exposure to tourism environments, which can promote behaviors such as commercial and transactional sex and elevated alcohol use. Nevertheless, little is known about how tourism contexts influence family dynamics, which, in turn, shape HIV risk. This qualitative study examined family relationships through in-depth interviews with 32 adults residing in Sosúa, an internationally known destination for sex tourism. Interviewees situated HIV risk within a context of limited employment opportunities, high rates of migration, heavy alcohol use, and separation from family. This study has implications for effective design of health interventions that make use of the role of the family to prevent HIV transmission in tourism environments.

Keywords: Dominican Republic, tourism, family, sexual risk behavior, HIV/AIDS

INTRODUCTION

The Caribbean is the region with the highest HIV prevalence in the world outside of Sub-Saharan Africa, with nearly 75% of these cases situated in Hispaniola, the island shared by the Dominican Republic (DR) and Haiti (UNAIDS, 2010). Tourism areas in the Caribbean have consistently been linked with high HIV prevalence due to their distinct ecological contexts that facilitate sexual risk behavior and disease transmission (Forsythe, Hasbun, & Butler de Lister, 1998; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2011; Kempadoo, 1999; Padilla, 2007; Padilla, Guilamo-Ramos, Bouris, & Reyes, 2010).

Despite this, there is a general absence of empirical literature that examines HIV transmission in tourism areas and its impact on families residing in communities in close proximity to geographic areas of heightened HIV vulnerability. The literature on sex workers and tourism in the DR is well-established (for men who have sex with men: De Moya, Garcia, Fadul, & Herold, 1992; Padilla, 2007; Padilla et al., 2008; for female sex workers: Brennan, 2004a, 2004b; Cabezas, 2009; Kerrigan et al., 2003; for hotel employees: Forsythe et al., 1998). However, less attention has been placed on understanding family relationships and the family lives of individuals living within tourism contexts, the relationship between tourism and alcohol use, HIV risk, and commercial and transactional sex and on the potential role of the family as an important target in HIV prevention. Contextual factors that affect family relationships, contributing to heightened HIV vulnerability and increased sexual risk behavior in tourism environments, warrant further consideration to better understand how families are impacted by the DR and broader Caribbean tourism industry.

Changes in the Dominican Economic Landscape

The DR’s economy and workforce have experienced sweeping changes in the last several decades, transforming a predominantly agrarian society into one of international interdependence (Pomeroy & Jacob, 2004). Tourism has become the greatest economic boom in the DR in an era of increasing globalization, driven predominantly by American and European investment (Roessingh & Duijnhoven, 2004). In 2010, the DR received more than 4.1 million stay-over visitors, equal to over 40% of its total population and considerably more than any other Caribbean country (CTO, 2011). The tourism sector, including formal and informal activities, now accounts for nearly 14% of total employment, producing nearly $7.3 billion in revenue and accounting for almost 16% of the country’s GDP (WTTC, 2011). Despite marked increases in the tourism sector in the DR, poverty and social inequality continue to persist in the lives of many native Dominicans. It is estimated that up to 43% of the population is living in poverty, and 16% of this population falls into the extreme poverty category, defined by the World Bank (2006) as average daily consumption of $1.25 or less.

Implications of Tourism Ecologies on HIV Risk Behavior

As a consequence of the expanding tourism industry, the DR has experienced rapid social, economic and demographic changes that have had far reaching implications for local populations living in and around tourism areas (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2011; Padilla et al., 2010). Advances in the tourism industry have occurred with limited consideration for the health and well-being of local residents living in the DR. Tourism is often associated with sexual risk behavior and HIV transmission, which have implications for health outcomes. A recently published report on HIV in the DR suggests that improvements in the epidemic are a “prevention success story in the Caribbean.” (Halperin, de Moya, Pérez-Then, Pappas, & Calleja, 2009, p. S52). However, it is important to note the lack of attention to tourism as a significant contextual factor in HIV transmission. Tourism areas have increasingly come to be viewed as geographic, social and behavioral spaces that function as “ecologies of heightened vulnerability,” a trend that has been documented throughout the Caribbean region (Kempadoo, 1999; Padilla et al., 2010). As a result, tourism has been cited as a contributing factor in the DR’s HIV/AIDS epidemic (Brennan, 2004a; Padilla, 2007; Padilla et al., 2010; UNAIDS, 2010).

Several specific mechanisms have been identified as potential explanatory factors that characterize the local tourism context in regards to heightened HIV risk: (1) population mixing among high and low HIV prevalence populations, including an unprecedented internal migration to tourism areas coupled with high numbers of foreign nationals converging in tourism areas (Padilla et al., 2010; Rojas, Malow, Ruffin, Roth, & Rosenberg, 2011), (2) high rates of tourism-related commercial and transactional sex (Brennan, 2004a; Kerrigan et al., 2003; Padilla, 2007) and (3) a tendency towards heavy alcohol use in tourism areas (Padilla et al., 2010; Parry, 2000; Room & Jernigan, 2000; Scribner, Theall, Simonsen, & Robinson., 2010). Together, these factors represent an ecology of risk and vulnerability for individuals residing or employed in tourism areas and their families.

Population Mixing among High and Low HIV Prevalence Populations

Population mixing of high and low HIV prevalence populations through sexual exchanges, a known facilitator in disease transmission (Anderson, 1996; Nepal, 2007; Yang & Xia, 2009), contributes to elevated rates of HIV in tourism areas in the DR where multiple vulnerable populations converge (Padilla et al., 2010). Tourism areas have become attractive to migrants from throughout the DR (Padilla, 2007; Padilla et al., 2010), who seek out tourist-centered employment opportunities as traditional forms of employment have decreased (Roessingh & Duijnhoven, 2004). Evidence suggests that migration to tourism areas may contribute to HIV risk among Dominican migrants and their regular or primary partners as a result of social isolation from family and social networks (Padilla, 2008). Social isolation can weaken normative control and social support for healthy behaviors among tourism workers, leading to a higher likelihood of engaging in behaviors pervasive in tourism environments such as sexual risk-taking, commercial and transactional sex and alcohol and substance use (Bronfman, 1998; Caldwell, Anarfi, & Caldwell, 1997; Wallace, 1993).

Tourism facilitates an influx of large numbers of foreign tourists, which further contributes to population mixing in the DR’s tourism areas. According to the Asociación Nacional de Hoteles y Restaurantes Inc. (ANHRI, 2011), foreign tourists to the DR tend to originate from the United States, Canada, and Western Europe—regions where HIV prevalence rates remain high, particularly among most at-risk populations (UNAIDS, 2010). Male tourists are well-documented for coming to the DR in search of female sex workers (Brennan, 2004a, 2004b; Cabezas, 2009; Kerrigan et al., 2003;). Additionally, the DR is a popular destination for disproportionately HIV-affected groups such as men who have sex with men (MSM), who are the target of websites that implicitly advertise sex tours to Dominican tourism destinations (see Monaga and Santo Domingo Direct as examples (Montgomery, 2011; Santo Domingo Direct, 2011).

Sex Work and Transactional Sex

Commercial and transactional sex, engaged in and supported by local Dominicans, Haitians, and tourists, has become a defining feature of the country’s tourism areas (Brennan 1998, 2003, 2004a, 2004b; Padilla, 2007; Padilla et al. 2010). Decreasing industrial and agricultural employment opportunities and an increasing demand for sexual services in the DR are major forces behind the availability of commercial and transactional sex. Cabezas (2008) argues that tourism “deskills and devalues Dominican workers, marginalizing them from tourism development and sexualizing their labor” (p. 22). Estimates of the number of sex workers in the DR have ranged from 70,000–130,000 individuals (USAID, 2008). The growth of transactional and commercial sex as a viable employment option for many Dominican men and women has been paired with other negative consequences of the expanding tourism industry in the DR, including a high risk of HIV infection reflected in high HIV prevalence rates among sex workers ranging from 3.3% to 6.4% (USAID, 2010). Studies have found that Dominicans who engage in commercial or transactional sex are commonly married or have primary sexual partners who are unaware of their involvement in sex work, suggesting the possibility of a chain of transmission from sex workers to their primary or regular partners (Padilla, 2007, 2008). Same sex behavior between local male residents and male tourists plays a considerable role within this chain and may be responsible for infecting significant numbers of both local males and females (Padilla, 2007, 2008). Such factors place both individuals residing and/or working in tourism areas and their families at increased risk.

Alcohol Use

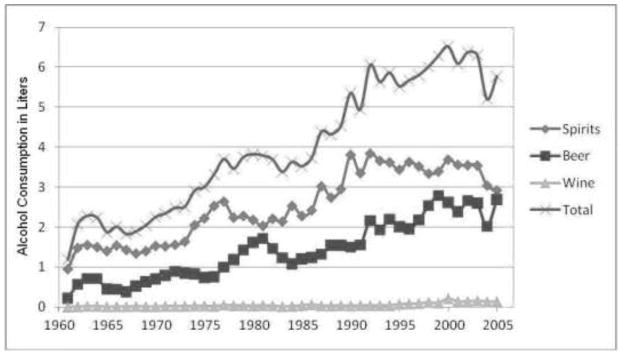

Despite the fact that alcohol is widely available in tourism areas, the role of alcohol in HIV transmission in tourism areas has been largely neglected in public health prevention efforts. Adult alcohol consumption has increased in the DR from 1.18 liters in 1961 to 5.75 liters in 2005, reaching a peak of 6.52 liters per person in 2000 (see Fig. 1) (WHO, 2008). The rise in alcohol consumption has been attributed to the growth of transnational alcohol companies that have heavily marketed and invested in Caribbean tourist destinations, including the DR, as a way to support the tourism industry (Parry, 2000; Room & Jernigan, 2000). In our previous research, 135 alcohol venues were identified in the target area of Sosúa, with 68% of those venues concentrated within 0.86 square kilometers (Guilamo-Ramos, Padilla, Meisterlin, McCarthy, & Lotz, in press). These data reflect a concentrated number of alcohol venues within the small area of Sosúa and high levels of alcohol consumption that is distinct from non-tourist locations in the DR.

Figure 1.

Adult alcohol consumption in the Dominican Republic, ages 15+ (WHO, 2008).

While HIV transmission in the DR continues to be primarily through sexual contact, there has also been limited data in the current epidemiological literature on the role of drugs and alcohol as contributing factors to HIV risk (Aguilar-Gaxiola et al., 2006). In tourism areas, studies have documented the relationship between alcohol use and sexual behavior (Forsythe et al., 1998; Kempadoo, 1999; Schwartz, 1999) including increased HIV-related sexual risk behaviors (Kalichman, 2010), as many alcohol venues are physically designed or situated in spaces that promote sexual encounters (Fritz et al., 2002; Kalichman, Simbayi, Vermaak, Jooste, & Cain, 2008; Morojele et al., 2004; Sivaram et al., 2008). The increased availability of alcohol also has ensuing health consequences for local families. For example, in a study of Dominican adolescents conducted in Sosúa, early sexual debut was found to co-occur with alcohol use (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2011). Dominican youth residing in close proximity to tourism areas were found to have alarmingly high rates of alcohol consumption and premature sexual debut (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2011).

Families and HIV Risk in Tourism Ecologies

The present study responds to a gap in the literature, which inadequately addresses the impact of tourism ecologies on family dynamics and sexual risk behavior in the DR. Specifically, the study seeks to understand how HIV risk behavior is shaped by family dynamics in tourism areas. Tourism areas, which are hosts to high HIV prevalence (Padilla et al., 2010), migration and population mixing (Padilla et al., 2010; Rojas, Malow, Ruffin, Roth, & Rosenberg, 2011), high availability and use of alcohol (Padilla et al., 2010; Parry, 2000; Room & Jernigan, 2000; Scribner, Theall, Simonsen, & Robinson, 2010), and commercial and transactional sex (Brennan, 1998, 2003,2004a, 2004b; Kerrigan et al., 2003; Padilla, 2007; Padilla et al., 2010), threaten the health and well-being of individuals involved in the tourism industry. While considerable work has examined how structural factors related to tourism contexts contribute to HIV risk (Padilla, 2008), little is known about how such environmental risk factors affect families of individuals living and working in these areas. The term “family” is used to encompass not only direct and immediate family members, but extended family members. Additionally, current or potential romantic partners are included in the notion of family as they are often involved in family life and are perceived as prospective family members. Our study investigated family relationships and sexual behavior of residents of a tourism area in the DR through themes identified in qualitative data from in-depth interviews with adults living in the tourism town of Sosúa. These key informant perspectives have the potential to inform HIV prevention efforts that make use of the valuable role that families play in influencing and mitigating HIV transmission risks associated with tourism environments.

METHOD

Participants

This study was based on data collected through semi-structured, in-depth interviews with adult males and females residing in and around the tourism area of Sosúa between May and June of 2009. All participants were engaged in commercial sex work, transactional sex or sexual relationships between tourists and people they meet in alcohol venues. Given the study’s aim to understand how tourism areas impact family relationships and HIV risk, alcohol venues were selected as locales for participant recruitment because they are concentrated in tourist areas and are establishments where risk behaviors such as formal or informal sex and alcohol use often occurs (Kalichman, Simvayi, Kaufman, Cain, & Jooste, 2007). Alcohol-use venues were defined as alcohol-serving businesses, such as bars, nightclubs and discos. Potential participants were informed about the research in detail in a private setting outside of the venue. Individuals who expressed interest in participating went through a brief verbal screen to determine participation eligibility. Inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) being between the ages of 18 to 50 years old; (2) reporting alcohol use within the past 30 days; and (3) being a local resident of Sosúa or one of its surrounding “barrios” or communities. A total of 32 adults were recruited and interviewed.

We employed a theoretical sampling method, a qualitative technique designed to maximize sample diversity on factors theorized to be important for understanding participant experiences in Sosúa (Hirsch et al., 2007). The technique is based on the theory that the constant comparative method of qualitative inquiry depends on the breadth of participant perspectives on the domains or themes of interest to the study. Based on ethnographic observations and interactions with local experts, our theoretical sampling approach diversified participants on the basis of four factors: (1) type of alcohol venue encountered (tourist versus local), (2) type of tourism work conducted (informal versus formal), (3) gender (female versus male), and (4) history of sexual-economic exchanges with tourists. We identified two types of alcohol venues--those that cater to tourists and those that cater to locals. Alcohol venues that cater to locals primarily attract local Dominican and Haitian residents and are not the primary venues where locals and tourists interact. In contrast, venues that cater to tourists typically attract both locals and tourists and serve as venues where population mixing frequent occurs. We recruited a minimum of two participants per cell in the 16-cell theoretical sampling matrix and purposefully sampled 16 adults from alcohol venues that cater to locals and 16 adults from alcohol venues that cater to foreign tourists to ensure representativeness of our sample. Important to note is that the sample recruited was not mutually exclusive along the four characteristics.

The sample was comprised of 16 men and 16 women. The mean age of participants was 36 years for men and 26 years for women. The marked difference in the average ages between male and female participants can be attributed to reports that younger women are in higher demand and are more marketable for sex work (Gupta, 2002; Wawer, Podhisita, Kanungsukkasem, Pramualratana, McNamara, 1996). Approximately two-thirds of the men (n = 10) were single, five were married, and one was divorced. Among the women, over three-quarters (n = 13) were single, two were married, and one was divorced. The majority of participants (n = 26) had children. Thirteen men and 13 women had completed primary school or had some secondary school education, three men and one woman had secondary school diplomas, and two women had completed some post-secondary schooling. The participant sample was geographically diverse, with the majority of subjects originating from outside of Sosúa (75%). A significant portion of the sample had migrated from the large, urban centers of Santo Domingo (25%) and Santiago (18.8%). Puerto Plata (6.3%) and other North Coast Towns (15.6%) were also represented in the sample. The diversity of the participant sample reinforces existing evidence that tourism towns are places where foreigners converge and where internal migration from non-tourism areas occurs.

Procedure and Measures

Research for the study was conducted in and around Sosúa, a tourism town located in the province of Puerto Plata on the north coast of the DR. Sosúa and the surrounding areas have attracted a community of wealthy Dominicans and expatriates who, with help from the government, began investing in and developing the tourism economy during the 1970s and 1980s (Kermath & Thomas, 1992). The area now has a well-established tourism industry and a highly diverse population of Dominican, Haitian, and foreign tourists, employees of the various hotels, restaurants, shops and other tourism-related businesses, a diverse array of informally employed migrant tourism laborers, and permanent local residents, many of whom have turned to the tourism industry as more traditional sources of employment have largely disappeared. Sosúa is internationally known as a destination for sex tourism and has been dubbed as a “sexscape” due to the prominence of sex tourism to the local economy (Brennan, 1998, 2003, 2004a, 2004b).

Participants were interviewed two times with each interview lasting between 1–2 hrs. On average, the time between the first and second interview was two months. The first interview focused primarily on family history, work history, migration, and relationships, while the second interview focused on topics including sexual practices, relationships with tourists, commercial and transactional sex, and perspectives on HIV/AIDS. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were used to ascertain specific information about key topics. Interviews were held in private, neutral settings in the community to ensure confidentiality. Participants received an incentive of $10 for each interview.

Interviews were recorded on digital audio recorders, which were then transcribed for analysis. Interpretation consisted of thematic analysis of participant narratives in response to a set of semi-structured interview questions. Transcripts were imported into ATLAS.ti computer software program and coded for family-related themes. In vivo coding and analytic summaries were developed for each interview due to the large bodies of text to be analyzed (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Thomas, 2006). Additionally, a priori codes that related to topics of interest such as the family, sexual behavior and tourism, were developed based on our research questions before examination of the data (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). One page analytic summaries were developed that included key findings and themes from each participant’s narratives. A codebook was created with codes and subcodes along with descriptions of the criteria for inclusion and exclusion. Examples of narratives applicable for each code were also identified for research staff.

Six coders initially coded a small subset of the interviews to ensure viability of the codebook and consistency between coders. This provided an opportunity for the principal investigator to ensure that all coders were skilled at using the codebook and that any discrepancies could be easily rectified. The codebook was revised after reflection and discussions among the research team with disagreements in coding being resolved through frequent team discussion and careful refinement of the coding. These systematic and critical discussions guided modifications and supported revisions that were made to the codebook. All transcripts were then coded by one of the six coders. Each coder independently recorded and calculated the number of times that each code and subcode occurred in the data. The coders compared the correspondence in the data and settled disagreements through discussions between all the coders. The frequent research team discussions and codebook modifications led to strong levels of intercoder reliability between coders (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Analysis involved the examination of the range of responses related to the themes of analytic interest. “Vertical” analysis techniques, where one engages in detailed interpretations of the data, were utilized to first decontextualize segments of the data for closer and focused analyses (Yardley, 2000). “Horizontal” analysis techniques, where one examines overall themes in the data, were then used to recontextualize the narratives within the larger context of the participant’s experience and behavior (Yardley, 2000). This allowed us to develop explanations for differences in the experiences among the participants.

RESULTS

Prominent Themes

Several primary themes emerged from the qualitative analysis of the in-depth interviews conducted for this study. These interviews reinforce and add to the evidence that tourism environments impact family dynamics and sexual risk. Specifically, high rates of alcohol use, commercial and transactional sex, sexual risk-taking behaviors, and population mixing were characteristic of Dominican tourism ecologies. The following themes illuminate how families were influenced by the DR’s tourism industry, which, in turn, affect sexual behavior and subsequent HIV risk.

Population mixing and families

Study participants described broad patterns of migration and population mixing. Several interviewees described their move to Sosúa as motivated by a search for economic opportunities when their communities of origin did not have any to offer. One woman from Sosúa explained, “There are more benefits, because look, when there are a lot of tourists, there are many sources of work. There are a lot of jobs. The people make good money, but imagine if you were somewhere else, where there is no tourism, it is more difficult for you to find another job, and you make less…” (female, age 24). Most participants saw the prospect of work in Sosúa’s tourism industry as one of the few employment opportunities available since more traditional forms of employment have disappeared. For example, as one woman from Santiago stated, “I was unemployed after the factory where I worked had closed when a friend of mine suggested I come to Sosúa. She said people earned good money there, so I decided to move” (female, age 24). Another interviewee noted her motivation for relocating to a tourism town, “Since I’m young, I would like another life besides this one. Because sometimes you have to do something not for yourself, but out of necessity” (female, age 23). This comment reveals the participant’s willingness to relocate due to her perception that tourist destinations can offer the necessary economic prospects to transform her life and family.

This migratory pattern allows individuals from low HIV prevalence populations to engage with populations with high HIV prevalence. A participant noted, “If we are where the tourism is, we can make a hundred pesos more easily. What would it [Sosúa] be without tourism?” (male, age 50). As individuals migrate to tourism areas for job opportunities, they often leave family members behind, which has implications for family structures and relationship dynamics.

Specifically, caring for family members was the primary motivating factor behind participants’ search for employment opportunities in Sosúa. As one participant stated, “… as parents we have to do these things to be able to sustain our children, and I decided to say ‘Well, let me look for another job, this one is not satisfactory for me to take care of myself and [my daughter],’ and I told myself that she deserved better. And so I came here to find something better” (male, age 34). Most study participants maintain relationships with extended family members who reside throughout the DR and abroad, and discussed their efforts to support family when income allows. One interviewee reported, “Sometimes my dad doesn’t work and if I have a thousand pesos, [I’ll say] ‘Here--take a thousand pesos and buy something for the house” (female, age 24). The above reports demonstrate the need to better understand not only how tourism economies affect residents of such areas, but also what impact they have on extended family members who rely on financial support from a distance.

Sex work and families

Study participants described diverse forms of participation in the tourism industry, including such activities as bartending, waitressing, guiding tours, and event promotions in addition to their involvement in sex work. Specifically, formal employment activities in tourism are often insufficient to make ends meet. Study participants described turning to transactional and commercial sex work to supplement their regular employment. Sex work was critical for economic subsistence, particularly among participants with family members to support. “Because to survive they have to sell [their body]. Because the little that she earns is not enough to maintain a family” (male, age 33). Interviewees ranged in their identification with commercial sex work activities, which some participants contextualized in the form of longer-term romantic relationships with foreigners. “You know what happens…there are also times when these women, many times, when they fall in love with the gringos, you see. And it is no longer just a job. You understand? It is more for pleasure” (male, age 31).

Adding to the population mixing found in Sosúa and other tourism regions in the DR is the diversity of the sexual partners that study participants identified, including not only Dominicans from throughout the country, but also partners from abroad, frequently North American and European countries. “Because, as I said: I’m not here for the money. I am here to find me a man, get married to a foreigner and get out of this country. Here there is no life in this country” (female, age 24). Another interviewee explained her reasons behind her preference to meet and marry a foreigner rather than a native from the DR. “Because I am already at an age where I want to settle down, to have a man who values me, to have a family. With Dominican men, this almost never happens” (female, age 28). These reports demonstrate the link that is often made between sex work and long term economic and family stability. While many engage in sex work for immediate monetary needs, the opportunity to establish a family and “change your life” is often used to justify involvement in the tourist industry and in sex work with foreigners.

Hence, tourist areas and the opportunity to engage in sex work have offered locals with alternative options for family life. At the same time, these opportunities can compromise the potential of having a faithful or loyal partner. Sexual concurrency, both within and outside the context of formal sex work, is common in Sosúa, especially for Dominican men. Male and female participants alike described how common it is for a man to have one consistent primary or regular partner, while also seeing other women and in certain cases, men, as more casual partners on the side. One male participant stated, “Well, you know that us Dominican men, we are--how should I say it--unfaithful…yes, a little friend will appear for this and that, but I try not to let [my girlfriend] find out. I try to be as discrete as possible” (male, age 34). While this participant’s involvement in sex work was motivated by economic needs, he illustrates that sexually concurrency is also facilitated by his disposition to have multiple sexual partners and the increased opportunities for multiple relationships in tourism areas. Hence, the greater availability of sexual interactions in tourism areas contributes to men’s capacity to engage in this behavior. Most female study participants complained about this phenomenon, and described difficulty in finding a faithful Dominican partner. “The street is abundant with this type [of man], they go around picking up women, one here, one there. [They are] not with one woman, but with lots of different women” (female, age 23). Hence, this participant describes frustration towards not only the unfaithfulness of Dominican men but also the increased opportunity for sexual concurrency in tourism areas.

While relationships in tourism areas can take the form of trusting and committed partnerships as well as transactional arrangements, the non-disclosed sexual concurrency that frequently occurs can contribute to sexual health outcomes. Specifically, participants cited protective behaviors as contingent upon specific relationship dynamics. For example, a male participant explained, “There are gringos that say, ‘No, I’ll give you enough--100 dollars, 150, 200--without a condom…and the women go with them” (male, age 44). Hence, economic need of families facilitates risky behaviors among individuals. Additionally, the perception of a being in a trusting relationship can determine condom use. One interviewee explained that “…We’re going to have a year together and I said: I’m going to trust you. But then, I trusted in him and I ended up pregnant. That is when I found out that he had a wife. Then, I threw him out of the house” (female, age 37). A male participant explained, “You are looking for means of prevention, but it does not happen. But there is one factor. The factor is that you can be faithful, but you do not know if your wife is faithful. Your wife may be true, but she does not know how faithful you are” (male, age 31). These reports demonstrate that the availability of sex work and non-disclosed sexual concurrency in tourism areas can impact family relationships and partner dynamics, presenting barriers in the prevention of HIV/STI transmission and unplanned pregnancy.

Alcohol use and the family

Romantic relationships and sex work in Sosúa are situated within a tourism context that encourages alcohol use. “Because in reality, everyone who comes to Sosúa is involved in [drugs and alcohol]…. Including prostitutes, motorcycle taxi drivers, the whole world is in it” (male, age 35). Some even say that alcohol use is what sells other aspects of the local economy. “It is to say that there are two things that sell, the drink and the women. So, the one who has his bar sells the drink and the woman…you do the two things at the same time” (male, age 33). Even study participants who stated that they do not enjoy drinking alcohol reported being pressured to drink during their interactions with tourists. “If you go out with gringos and you order a water or a coca cola, they don’t like it” (female, age 22). Another participant explained further, “The client is having fun and if you are not having fun, ah no…then the guy will get bored and then what happens…. Do you understand? So, he needs me to be feeling the same as him. Get it? So you have to do the same…I drink to keep the same rhythm that he has” (male, age 31). In addition to pressure from tourists and clients, study participants described other environmental factors in tourism areas that facilitated drinking, such as ordering a juice drink that somehow arrives with alcohol in it or receiving free drinks, happy hour deals, and other drink specials.

Participants described how Sosúa’s context of drug and alcohol use interferes with one’s family life and relationship dynamics. One woman in Sosúa complained how her previous husband would leave and return home at unreasonable hours, leading to many conflicts between them. “…he would leave at five in the morning until four in the morning. If you have a relationship, you know that your husband leaves at five in the morning and arrives at eight. So, things didn’t go very well” (female, age 24). She further explained that he would be at alcohol venues such as bars and discos, which led to infidelity in the relationship. These reports demonstrate that the lifestyle facilitated by the availability of alcohol venues in tourism areas is detrimental to family functioning and family structures. Sex work, sexual concurrency and infidelity, as a result, contribute to HIV vulnerability. One participant explained how alcohol impairs judgment in regards to sexual behavior. “Because yes, because of the environment, the drinking, the women, and when you already have rum on the brain--your vice--the thing that they want is sex. It is just that they don’t want to take care of themselves when this is what they want” (female, age 22)

Additionally, several study participants connected alcohol use in the family with reports of intimate partner violence. One man described the relationship between alcohol and violence, “Alcohol is one of the problematic drugs that has destroyed more homes. Because if we can see the instability that many homes have had, to the extreme of divorce, separation, physical aggression, abandonment--including of children, because the person doesn’t pay attention, he is only thinking about the alcoholic drink. And this brings consequences; it destroys everything that you have” (male, age 31). Another woman described a former partner this way: “We used to have a lot of problems before, almost always. Because he used to like to drink a lot, always, always, always. We were together for eight years, and he was always violent with me. But I put up with all of this, even working and paying for the house. My money went for the house and to him to go out and drink it away” (female, 24). Some interviewees cited alcohol use and violence as the reasons why they eventually chose to leave or end their relationships. “Yes, I was knocked out…. In this life many things happen and I was already in the street, I went after my money and became independent for myself. I never went back to my house. Never” (female, age 36). Study participants validated existing evidence that intimate partner violence in the DR, is commonplace, and that alcohol has a particularly strong role in fomenting this known contributor to HIV risk, particularly in tourism contexts where alcohol venues are concentrated. Moreover, frequenting of alcohol venues in tourism areas cited by participants due to their involvement in sex work highlights the nexus between alcohol use, intimate partner violence and sexual risk behavior.

Hence, Sosúa’s context of heavy alcohol use was seen by many interviewees as corrupting any chance of having a quality family life while residing in the area. “My children don’t go out…. Imagine if I were to live in this place…seeing the things that go on 24 hours a day. I don’t think it would be good for someone to have your family’s house close by. For example, when you are raising a child, and 24 hours a day [you hear]: ‘cunt, cunt, cunt…’ What child is then going to pray the Our Father? He is going to say ‘cunt,’ this is what I think is no good” (female, age 37). The perception of risk in Sosúa extends to interviewees’ family members, who, as many study participants reported, consistently remind their loved ones to take care and avoid “catching a disease from the street.” It is unclear, though, what impact such kinds of advice from family actually has on individuals’ decisions to engage in sexual risk behaviors.

DISCUSSION

Our study provided insights into how tourism areas of the DR and broader Caribbean region impact families and shape HIV risk and sexual behavior. We identified how contextual factors of tourism areas, specifically population mixing, sex work and alcohol use, influenced family dynamics. While much of the focus on tourism environments and HIV risk has been on individuals, such as sex workers or drug users, less attentions has been paid to how these contexts shape or change family units. Given the importance of family relationships in the Dominican Republic, the shift in family dynamics as a result of factors associated with tourism environments impacts individual HIV risk and sexual behavior.

Our findings highlighted that the economic opportunities associated with tourism areas compel many individuals to migrate, often leaving families behind. While the desire to financially support family members was often related to this move, separation from family members can lead to social isolation, facilitating risky behaviors and encounters with high HIV prevalence populations. Additionally, the availability of sex work in tourism areas contributes to individual engagement in risk behaviors that are mediated by family relationships and partner dynamics. As individuals envision sexual partners as potential family members, they may be more willing to engage in risky behaviors. Additionally, as individuals are motivated by the need to support family members, they may be more willing to engage in risky sex, such as sex without protection. Lastly, our findings demonstrated that the availability of alcohol in tourism areas greatly impact family functioning and can contribute to intimate partner violence. As a result, sexual concurrency and changes in family structures influence sexual risk behavior and HIV vulnerability. In sum, individual engagement with risk behavior in tourism areas is often mediated by family relationships.

As tourism environments shape family dynamics, participants confirmed that the family plays an important role in shaping their decisions and behaviors. Our findings were consistent with the well-established literature related to familism among Latinos and have important applied implications for the development of family based HIV prevention efforts (Prado et al. 2007).

Studies document that individuals with higher levels of familism are less likely to practice high HIV risk behaviors and more likely to engage in healthy behaviors (Lescano, Brown, Raffaelli, & Lima, 2009; Muñoz-Laboy, 2008). This suggests that strengthening family systems, particularly in cultures where families hold important value such as the Dominican Republic, can be effective in reducing HIV risk behavior as family involvement can serve as a powerful protective mechanism against unsafe behavior (Guilamo-Ramos, 2010; Prado et al., 2007). While efforts to reduce HIV vulnerability in tourism areas have primarily focused on the individual or on structural interventions that aim to change environments where risk behavior occurs (Des Jarlais, 2000; Kerrigan et al., 2006), our findings demonstrated that families may be an important component to HIV prevention efforts.

In resource-poor countries like the DR, families are typically the basic unit of care and previous research has widely documented the important role of family for Latinos (Prado et al., 2007). There has been increased interest in the development and implementation of family based HIV prevention and treatment interventions globally (McKay et al., 2007; Richter, 2010; Soletti, Guilamo-Ramos, Burnette, Sharma, & Bouris, 2009). Families have been clearly identified to be important in HIV risk; however, they have been an underutilized resource in the global response to HIV/AIDS (Coates, Richter, & Caceres, 2008; Paruk, Petersen, Bhana, Bell, & McKay, 2005). Such approaches may be particularly useful for tourism contexts and resource poor environments such as the Dominican Republic. An area for further research is to explore the feasibility and acceptability of HIV prevention interventions in Caribbean tourism areas that incorporates and takes full advantage of the protective aspects of the family on individual HIV risk behavior.

Despite the protective elements of family life on individual HIV risk, families can also exacerbate risk by increasing an individual’s exposure to HIV risk or serve as an important motivation for involvement in risk behavior. Traditionally, HIV prevention efforts have prioritized focusing on individual behaviors among specific high risk groups as opposed to contextual and environmental risk factors. Our data identified Dominican families as a potential contextual source of risk and protection for individual HIV transmission. Additionally, environmental factors, such as the availability of alcohol and commercial or transactional sex, can directly expose individuals to HIV. Prevention efforts may need to provide ways to contend with family based social factors facilitative of HIV risk and directly target correlates of HIV risk such as family based interpersonal violence and alcohol use and its impact on the family. Whether it be disclosure about sexual concurrency among men who have sex with men (Padilla, 2008) or marriage norms where the implicit trust of the partnership trumps any other value (Hirsch, Higgins, Bentley, & Nathanson, 2002; Hirsch et al., 2010), families play a key role. Preventive interventions may also need to address social norms that may increase the acceptability of factors implicated in HIV risk. For example, norms of masculinity may increase the acceptability of violence within the family or impede efforts to reduce risky behaviors, highlighting the importance of addressing social norms as part of intervention efforts (Barrington et al., 2009). Furthermore, direct involvement in HIV risk behavior oftentimes has a familial component. For example, sex work and transactional sex are oftentimes a means to support one’s family economically. This is particularly true within contexts of low resources and limited economic opportunities such as Dominican tourism areas. Important to note are programs and existing literature that support the development of alternative economic opportunities for sex workers with children (Beard et al., 2010) and programs that empower Dominican women to control their economic resources through micro-credit loans that demonstrate HIV protective behaviors (Ashburn, Kerrigan, & Sweat, 2008). These programs are potential opportunities for reducing HIV risk, and merit further attention. Important to note is that our results assumed a broad definition of the family to include not only immediate family members but sexual partners and potential romantic relationships. Also merited is a better understanding of how Dominicans define families and the role that different types of family members play in HIV risk.

In sum, the Caribbean region, particularly tourism areas, are disproportionately burdened by HIV prevalence. Specific tourism environmental factors shape family dynamics, and these relationships have important implications for the sexual risk behavior of individuals in these contexts. However, tourism areas have tended to be overlooked in the global public health response to HIV prevention. One natural source of both HIV risk and protection is the family. Previous research has highlighted familial units as essential in responding to HIV/AIDS (Richter, 2009, 2010), and further research is needed to continue exploring the role of the family in HIV transmission in the DR. In 2012, the global HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment community recognized an AIDS-free generation as a tenable possibility. Specifically, the development of combination prevention strategies that integrate biomedical, behavioral and structural interventions suggests, for the first time since the inception of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, that we can envision an end. Despite the widespread optimism associated with these advancements, the important role of families in responding to and preventing HIV infections remains largely invisible. Our study highlights the importance of families in both treatment and prevention efforts and emphasizes the need to address families in the public health response not just in the Dominican Republic, but in countries with limited resources and high HIV risk.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n = 32)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (in years) | |

| Under 25 | 12 (37.5%) |

| 25–30 | 3 (9.4%) |

| 31–40 | 12 (37.5%) |

| Over 40 | 5 (15.6%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 16 (50.0%) |

| Female | 16 (50.0%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 23 (71.9%) |

| Married | 7 (21.9%) |

| Divorced | 2 (6.3%) |

| Town of Origin | |

| Migrated to Sosúaa | 24 (75.0%) |

| Native to Sosúa | 8 (25.0%) |

| Education Level | |

| Primary School 1–4 | 6 (18.8%) |

| Primary School 5–8 | 11 (34.3%) |

| Some Secondary School | 9 (28.1%) |

| Completed Secondary School | 4 (12.5%) |

| Some Post-Secondary School | 2 (6.3%) |

Note: High levels of migration to areas associated with tourism and sex work

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R21AA018078). We would like to express special thanks to Sarah Leavitt for her comments and feedback on the article.

References

- Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Medina-More ME, Magaña CG, Vega WA, Alejo-Garcia C, Quintanar TR, et al. Illicit drug use research in Latin America: Epidemiology, service use, and HIV. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84S:S85–S93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RM. The spread of HIV and sexual mixing patterns. In: Mann J, Tarantola D, editors. AIDS in the world. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 457–514. [Google Scholar]

- Ashburn K, Kerrigan D, Sweat M. Micro-credit, women’s groups, control of household money: HIV-related negotiation among partnered Dominican women. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:396–403. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asociación Nacional de Hoteles y Restaurantes Inc. (ANHRI) Estadísticas turísticas boletín abril de 2011. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.asonahores.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=23&Itemid=60.

- Barrington C, Latkin C, Sweat MD, Moreno L, Ellen J, Kerrigan D. Talking the talk, walking the walk: Social network norms, communication patterns, and condom use among the male partners of female sex workers in La Romana, Dominican Republic. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:2037–2044. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard J, Biemba G, Brooks MI, Costello J, Ommerborn M, Bresnahan M, et al. Children of female sex workers and drug users: A review of vulnerability, resilience and family-centered models of care. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2010;13(S2):S6–S13. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-S2-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan D. Everything is for sale here: Sex tourism in Sosúa, the Dominican Republic. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan D. When sex tourists and sex workers meet: Encounters within Sosúa, the Dominican Republic’s sexscape. In: Gmelch SB, editor. Tourists and tourism. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press; 2003. pp. 314–XXX. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan D. What’s love got to do with it? Transnational desires and sex tourism in the Dominican Republic. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2004a. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan D. Women work, men sponge, and everyone gossips: Macho men and stigmatized/ing women in a sex tourist town. Anthropology Quarterly. 2004b;77:705–733. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfman M. Mexico and Central America. International Migration. 1998;36:609–642. doi: 10.1111/1468-2435.00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas A. Tropical blues: Tourism and social exclusion in the Dominican Republic. Latin American Perspectives. 2008;35:21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas A. Economies of desire: Sex and tourism in the Dominican Republic and Cuba. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC, Anarfi JK, Caldwell P. Mobility, migration, sex, STDs and AIDS: An essay on Sub-Saharan Africa with other parallels. In: Herdt G, editor. Sexual cultures and migration in the era of AIDS: Anthropological and demographic perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. pp. 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO) Latest statistics 2010. Barbados: Caribbean Tourism Organization; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.onecaribbean.org/statistics/2011statistics/default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Coates TJ, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioral strategies to reduce HIV transmission: How to make them work better. Lancet. 2008;372:669–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Moya EA, Garcia R, Fadul R, Herold E. Report: Sosúa sanky-pankies and female sex workers: An exploratory study. Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: La Universidad Autonoma de Santo Domingo; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC. Structural interventions to reduce HIV transmission among injecting drug users. AIDS. 2000;14(S14):S41–S46. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2006;5:80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe S, Hasbun J, Butler de Lister M. Protecting paradise: Tourism and AIDS in the Dominican Republic. Health Policy and Planning. 1998;13:277–286. doi: 10.1093/heapol/13.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz KE, Woelk GB, Bassett MT, McFarland WC, Routh JA, Tobaiwa O, Stall RD. The association between alcohol use, sexual risk behavior, and HIV infection among men attending beer halls in Harare, Zimbabwe. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V. Dominican and Puerto Rican mother-adolescent communication: Maternal self-disclosure and youth risk intentions. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2010;32:197–215. [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Lushin V, Martinez R, Gonzalez B, McCarthy K. HIV risk behavior among youth in the Dominican Republic: The role of alcohol and other drugs. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care. 2011;10:388–395. doi: 10.1177/1545109711419264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Padilla M, Meisterlin L, McCarthy K, Lotz K. Tourism ecologies, alcohol venues and HIV: Mapping spatial risk. International Journal of Hispanic Psychology (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GR. Vulnerability and resilience: Gender and HIV/AIDS in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin D, Antonio de Moya E, Pérez-Then E, Pappas G, Calleja JG. Understanding the HIV epidemic in the Dominican Republic: A prevention success story in the Caribbean? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;51:S52–S59. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a267e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JS, Higgins J, Bentley ME, Nathanson CA. The social constructions of sexuality: Marital infidelity and sexually transmitted disease—HIV risk in a Mexican migrant community. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1227–1237. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JS, Meneses S, Thompson B, Negroni M, Pelcastre B, del Rio C. The inevitability of infidelity: Sexual reputation, Social geographies, and marital HIV risk in rural Mexico. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:986–996. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JS, Wardlow H, Smith DJ, Phinney HM, Parikh S, Nathanson CA. The secret: Love, marriage, and HIV. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC. Social and structural HIV prevention in alcohol-serving establishments. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33:184–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of empirical findings. Prevention Science. 2007;8:141–151. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Jooste S, Cain D. HIV/AIDS risks among men and women who drink at informal alcohol serving establishments (Shebeens) in Cape Town, South Africa. Prevention Science. 2008;9:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempadoo K. Continuities and change: Five centuries of prostitution in the Caribbean. In: Kempadoo K, editor. Sun, sex and gold: Tourism and sex work in the Caribbean. New York: Rowman and Littlefield; 1999. pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kermath BM, Thomas RN. Spatial dynamics of resorts: Sosúa, Dominican Republic. Annals of Tourism Research. 1992;19:173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan D, Moreno L, Rosario S, Gomez B, Jerez H, Barrington C, Weiss E, Sweat M. Environmental-structural interventions to reduce HIV/STI risk among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:120–125. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan D, Moreno JEL, Rosario S, Katz J, Celentano D, Sweat M. Environmental-structural factors significantly associated with consistent condom use among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. AIDS. 2003;17:415–423. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200302140-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescano CM, Brown LK, Raffaelli M, Lima L. Cultural factors and family- based HIV prevention intervention for Latino Youth. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:1041–1052. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Block M, Mellins C, Traube DE, Brackis-Cott E, Minott D, et al. Adapting a family-based HIV prevention program for HIV-infected preadolescents and their families. Social Work in Mental Health. 2007;5:355–378. doi: 10.1300/J200v05n03_06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery A. Nightlife. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.monaga.net/website/en/nightlife.

- Morojele NK, Kachieng’a MA, Nkoko MA, Moshia KM, Mokoko E, Parry CDH, et al. Perceived effects of alcohol use on sexual encounters among adults in South Africa. African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies. 2004;3:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Laboy MA. Familism and sex regulation among bisexual Latino men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:773–782. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9360-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nepal B. Population mobility and spread of HIV across the Indo-Nepal border. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2007;25:267–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla MB. Caribbean pleasure industry: Tourism, sexuality, and AIDS in the Dominican Republic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla MB. The embodiment of tourism among bisexually-behaving Dominican male sex workers. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:783–793. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla MB, Castellanos D, Guilamo-Ramos V, Reyes AM, Sánchez Marte LE, Soriano MA. Stigma, social inequality, and HIV risk disclosure among Dominican male sex workers. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla MB, Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Reyes AM. HIV/AIDS and tourism in the Caribbean: An ecological systems perspective. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:70–77. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CDH. Alcohol problems in developing countries: Challenges for the new millennium. Suchtmed. 2000;2:216–220. [Google Scholar]

- Paruk Z, Petersen I, Bhana A, Bell C, McKay M. Containment and contagion: How to strengthen families to support youth HIV prevention in South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2005;4:57–63. doi: 10.2989/16085900509490342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pina D. Dominican Republic: Remittances for development. Inter Press Service; 2007. Retrieved from http://ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=39306. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy C, Jacob S. From mangos to manufacturing: Uneven development and its impact on social well-being in the Dominican Republic. Social Indicators Research. 2004;65:73–107. [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, Schwartz SJ, Feaster D, Huang S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a parent-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:914–926. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter LM. An introduction to family-centered services for children affected by HIV and AIDS. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2010;13(S2):S1–S6. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-S2-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter LM, Sherr L, Adato M, Belsey M, Chandan U, Desmond C, et al. Strengthening families to support children affected by HIV and AIDS. AIDS Care. 2009;21:3–12. doi: 10.1080/09540120902923121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessingh C, Duijnhoven H. Small entrepreneurs and shifting identities: The case of tourism in Puerto Plata (Northern Dominican Republic) Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change. 2004;2:185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas P, Malow R, Ruffin B, Roth E, Rosenberg R. The HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Dominican Republic: Key contributing factors. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care. 2011;10:306–315. doi: 10.1177/1545109710397770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Jernigan D. The ambiguous role of alcohol in economic and social development. Addiction. 2000;95:S523–535. doi: 10.1080/09652140020013755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santo Domingo Direct. Santo Domingo direct. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.mariosessions.com/santodomingoclubs.htm.

- Schwartz R. Pleasure island: Tourism and temptation in Cuba. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Scribner R, Theall KP, Simonsen N, Robinson W. HIV risk and the alcohol environment: Advancing an ecological epidemiology for HIV/AIDS. Alcohol Research and Health. 2010;33:179–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaram S, Srikrishnan AK, Latkin C, Iriondo-Perez J, Go VF, Solomen S, Celentano DD. Male alcohol use and unprotected sex with non-regular partners: Evidence from wine shops in Chennai, India. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;94:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soletti A, Guilamo-Ramos V, Burnette D, Sharma S, Bouris A. India-U.S. collaboration to prevent adolescent HIV-infection: The feasibility of a family-based HIV-prevention intervention for rural Indian youth. Journal of International AIDS Society. 2009;12:35–XX. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation. 2006;27:237–246. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/global_report.htm.

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID) A story to tell: Better health in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.usaid.gov/locations/latin_america_caribbean/pdf/USAID_Story_on_Health_in_LAC.pdf.

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Dominican Republic: HIV/AIDS health profile. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/aids/Countries/lac/domreppub_profile.pdf.

- Wallace R. Social disintegration and the spread of AIDS, II: Meltdown of sociogeographic structure in urban minority neighborhoods. Social Science and Medicine. 1993;32:887–896. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90143-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawer MJ, Podhisita C, Kanungsukkasem U, Pramualratana A, McNamara R. Origins and working conditions of female sex workers in urban Thailand: Consequences of social context for HIV transmission. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;42:453–462. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Document of the World Bank, the Inter-American Bank and the Government of the Dominican Republic Report No 32422-DO. 2006 Retrieved from http://irispublic.worldbank.org/85257559006C22E9/All+Documents/85257559006C22E9852572890074BCA1/$File/DominicanRepub0rtyAssessmentEnglish.pdf.

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global health atlas. 2008 Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/globalatlas/default.asp.

- World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) Travel and economic impact–Caribbean. London: WTTC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Xia G. Gender, migration, and unprotected causal and commercial sex: Individual and social determinants of HIV and STD risk among female migrants. In: Poston DC, Tucker J, Ren Q, Gu B, Zheng X, Wong S, Russell C, editors. Gender policy and HIV in China: The Springer series on demographic methods and population analysis. Vol. 22. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Yardley L. Dilemmas in qualitative health research. Psychology and Health. 2000;15:215–228. [Google Scholar]