Abstract

Objective

To compare patterns of site-specific cancer mortality in a population of individuals with and without mental illness.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional, population-based study using a linked dataset comprised of death certificate data for the state of Ohio for the years 2004–2007 and data from the publicly funded mental health system in Ohio. Decedents with mental illness were those identified concomitantly in both data sets. We used age-adjusted standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) in race- and sex-specific person-year strata to estimate excess deaths for each of the anatomic cancer sites.

Results

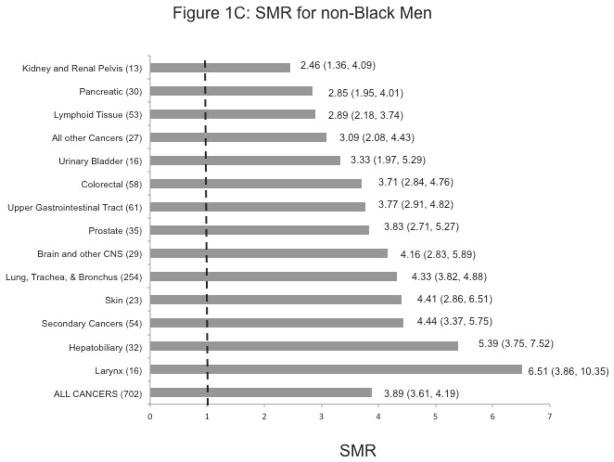

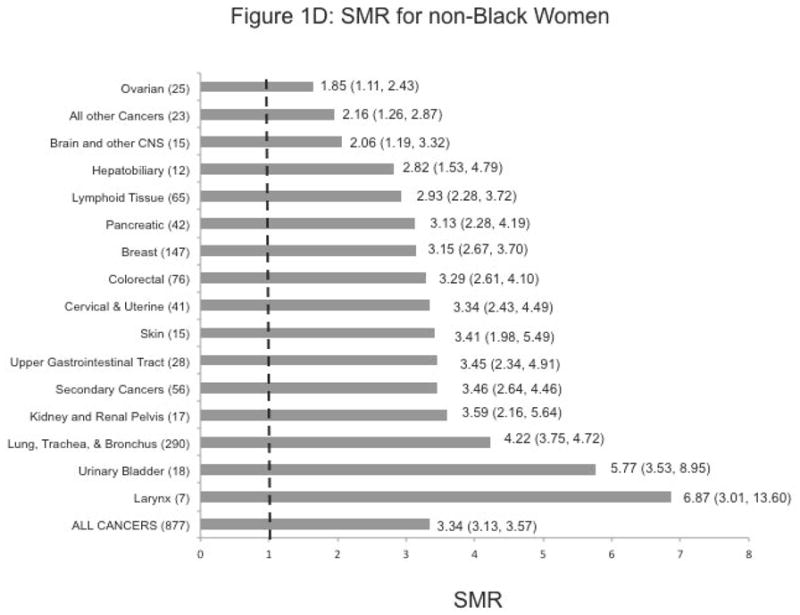

Overall, there was excess mortality from cancer associated with having mental illness in all of the race/sex strata: SMR: 2.16, (95% Confidence Interval: 1.85–2.50) for Black men; 2.63 (2.31–2.98) for Black women; 3.89 (3.61–4.19) for non-Black men, and 3.34 (3.13–3.57) for non-Black women. In all of the race/sex strata except for Black women, the highest SMR was observed for laryngeal cancer 3.94 (1.45–8.75) in Black men; 6.51 (3.86–10.35) and 6.87 (3.01–13.60) in non-Black men and women, respectively). The next highest SMRs were noted for hepatobiliary cancer and that of the urinary tract in all race/sex strata, except for Black men.

Conclusions

Compared to the general population in Ohio, individuals with mental illness experienced excess mortality from most cancers, possibly explained by a higher prevalence of smoking, substance abuse, and chronic hepatitis B or C infections in individuals with mental illness. Excess mortality could also reflect late-stage diagnosis and receipt of inadequate treatment.

Keywords: Mental Illness, Excess Mortality, Cancer

Introduction

Mental illness (MI) is an important public health problem in the United States (US) and globally. In the US alone, 1 in 4 adults (26.2%) suffer from a diagnosable MI in a given year (1). MI is associated with poor physical health (2). Patients with severe and persistent MI have many unattended medical needs attributed in part to fewer contacts with primary health care providers (3). Reduced life expectancy and high rates of premature death have been documented among individuals with serious MI, with these individuals dying as much as 15 to 25 years younger than the general population (4–5). As such, patients with MI constitute a vulnerable population, given their economic disadvantage (6), difficulty obtaining medical insurance (7), associated cognitive limitations, and lack of knowledge about their health and the health care system. At the same time, non-psychiatric physicians are typically poorly prepared to provide care to this complex population (8). Together, these factors may negatively affect their access to and benefit from medical care (9), which may impact both the risk for specific cancers and the process of screening, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer in this population.

Relative to cancer outcomes, a number of studies have documented cancer-related disparities associated with MI, including being diagnosed at an unknown stage of cancer (10), advanced-stage cancer (11), receipt of cancer treatment (10, 12–13), or survival (10, 12). Not surprisingly, therefore, excess mortality from cancer has been reported in MI patients, compared to their non-MI counterparts (14–16), although results have also varied across studies, cancer sites, demographic or psychiatric subgroups of the population (17–18).

In this study we seek to detail the broad category of deaths due to malignant neoplasms into specific anatomic sites across the age, sex, and race strata, and to compare the death rates of individuals with mental illness to those of the general Ohio population, using the person-year approach, to account for the length of follow-up period. Understanding the extent to which specific cancer diagnoses differ among individuals with and without MI holds both clinical and public health relevance. In particular, the findings will help to develop targeted preventive strategies, and to improve clinical care for this vulnerable group.

Methods

Data sources

This is a cross-sectional, population-based study, using a linked database comprised of death certificate data for the state of Ohio for the years 2004–2007, the Multi-Agency Community Services Information System (MACSIS), and the Patient Care System (PCS).

MACSIS is an automated payment and management information system for the publicly funded outpatient mental health services. It includes patient demographics, billing charges, service dates and diagnostic codes based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition text revision (DSM-IV TR) (19).

PCS has data from regional psychiatric hospitals across the state. It includes dates of admission and discharge, patient demographics, patient identifiers and a DSM-IV based diagnosis.

The Ohio death certificate file has data for all Ohio decedents. The underlying causes of death are coded based on the International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modifications, 10th Edition (ICD-10 CM).

Linkage of the three datasets was performed using a deterministic, multi-step process based on personal identifiers, including social security number (SSN), name, date of birth, and sex, consistent with other studies (20–22). Successful identification of a decedent in the death certificates and the MACSIS and/or the PCS files implied that the decedent had been a recipient of Ohio’s publicly funded mental health system, therefore an individual with mental illness. All sensitive identifiers, including SSN, name, and date of birth were removed from the version of the analytical file that was shared with investigators outside of the state mental health agency.

This study was considered exempt by the Institutional Review Boards of Ohio Department of Health and Case Western Reserve University.

Study Variables

The cause of death was determined using ICD-10 CM codes in the death certificate records, and deaths due to cancer (C00–C97), were parsed out (Table 1). Cancers were then categorized based on the anatomic cancer site by using the definitions provided in the SEER Training Modules of the National Cancer Institute (23), and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services classification (24).

Table 1.

ICD-10 codes for specific cancer sites

| Cancer Anatomic site | ICD-10 CM |

|---|---|

| 1. Upper gastrointestinal tract | C00–C16 |

| 2. Colorectal cancer | C18–21 |

| 3. Hepatobiliary cancer | C22 |

| 4. Pancreatic cancer | C25 |

| 5. Lung tissue cancer | C33–C34 |

| 6. Cancer of the larynx | C32 |

| 7. Skin cancer | C43–C44 |

| 8. Breast cancer | C50 |

| 9. Cervical and uterine cancer | C53–C55 |

| 10. Ovarian cancer | C56 |

| 11. Cancer of the prostate | C61 |

| 12. Urinary bladder cancer | C67 |

| 13. Kidney and renal pelvis cancer | C64–C65 |

| 14. Brain and other central nervous system (CNS) tissue | C70–C72 |

| 15. Cancer of the lymphoid and hemopoetic tissues | C81–C96 |

| 16. Secondary* and ill-defined cancers | C76–C80 |

| 17. All other cancers | C17, C23–C24, C26–C31, C37–C41, C44–C49, C51–C52, C57–C60, C62–C63, C66, C68–C69, C73–C75, and C97 |

Secondary cancer means that the anatomic site for the primary cancer was not listed in the death certificate, thus indicating that the patient died of cancer metastasis

To avoid errors that might have arisen at data entry (e.g., prostate cancer in a female decedent), we restricted the analysis for breast, ovarian, and cervical and uterine cancer to females, while for prostate cancer analysis was done only for males. We recognize that breast cancer rarely occurs in males (25).

The main variable of interest was the absence or presence of mental illness (0/1), which we coded as 1 when a decedent was identified in either MACSIS or the PCS files, and in the death certificate file.

Other variables of interest for this study were: decedent demographics i.e. year of birth, race, and sex, all retrieved from the death certificate dataset. Age was classified into five categories as follows: 1–14, 15–24, 25–44, 45–64 and 65+ years. Racial groups were dichotomized into Blacks vs. Non-Blacks. Blacks were comprised of African-Americans and persons of African descent, while Non-Blacks included whites and other racial minorities whose numbers were too small to maintain as separate categories for statistical analyses.

Study population

Our study population comprised all Ohio residents 1 year of age or older, who died of cancer in the years 2004–2007 (n=101,689). Of those, 4,284 were also identified through the above-referenced MACSIS and PCS files. However, 2,303 of the 4,284 never had claims in the MACSIS or the PCS, despite being enrolled in the system; and possibly due to deficiencies in the system, data on their enrollment as well as mental health diagnosis were largely absent. Consequently, we opted to group these 2,303 decedents with the general population. Thus, our study population included 101,689 Ohio decedents with cancer, 1,981 had documented mental illness, and we termed this group the mental illness decedents.

Analysis

Because persons seeking care from the publicly funded mental health system were not followed all through the 4-year study period, we used the person-year approach in our analysis. The total number of person-years corresponding to the 604,771 individuals with mental illness was 544,760. Based on the 11.3 million individuals residing in Ohio (our reference group), the number of person years was 45.4 million.

For the descriptive analysis, we obtained the proportion of decedents per category among those who had mental illness (MI) and among the entire Ohio population. All descriptive analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (Cary, North Carolina).

In addition to the descriptive analysis, using the indirect standardization method, we obtained the age-, race- and sex-specific Standardized Mortality Ratios (SMRs) by dividing the observed by the expected deaths. The stratum-specific expected number of deaths was obtained by multiplying the number of person-years in a stratum by the crude mortality rate in the Ohio population (from the 2000 U.S. Census) in that stratum. Confidence intervals (CIs) for the SMRs were calculated using version 4.11.19 of the online SMR calculator by the Emory University School of Public Health (26).

Results

Table 2 shows the distribution of lives (in person-years) for individuals with MI and the total Ohio population, in age-race-sex strata. Compared to the total Ohio population, we noted a markedly greater representation of younger individuals among those with MI.

Table 2.

Distribution of the total Ohio population and individuals enrolled in the publicly funded mental health system during the study period, in person-years.

| Age category | Black Men | Black Women | Non-Black Men | Non-Black Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (% of Total) | N (% of Total) | N (% of Total) | N (% of Total) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| MI* | Total Ohio | MI* | Total Ohio | MI* | Total Ohio | MI* | Total Ohio | |

| 1–14 | 23,890 (39.49) | 713,772 (28.97) | 12,176 (19.33) | 689,036 (25.14) | 57,797 (29.69) | 4,194,868 (21.40) | 32,739 (14.77) | 3,998,672 (19.39) |

| 15–24 | 12,046 (18.40) | 391,436 (15.89) | 11,264 (17.89) | 401,112 (14.63) | 37,087 (19.06) | 2,727,660 (13.93) | 38,163 (17.21) | 2,662,976 (12.91) |

| 25–44 | 14,699 (22.45) | 720,132 (29.22) | 19,581 (31.09) | 816,168 (29.77) | 53,944 (27.72) | 5,868,764 (29.97) | 74,666 (33.68) | 5,895,776 (28.59) |

| 45–64 | 13,964 (21.33) | 446,148 (18.10) | 17,684 (28.09) | 535,524 (19.54) | 42,166 (21.67) | 4,552,032 (23.24) | 65,787 (29.67) | 4,767,456 (23.12) |

| 65+ | 867 (1.32) | 192,580 (7.82) | 2,260 (3.59) | 299,320 (10.91) | 3,631 (1.87) | 2,241,656 (11.45) | 10,350 (4.67) | 3,297,472 (15.99) |

| Total | 65,466 (100.0) | 2,464,068 (100.0) | 62,964 (100.0) | 2,741,160 (100.0) | 194,624 (100.0) | 19,584,980 (100.0) | 221,705 (100.0) | 20,622,352 (100.0) |

MI: Individuals with mental illness enrolled in the publicly funded mental health system

Among those who had cancer (n=101,689), 1981 (1.95%) also had MI diagnosis (Table 3). The mean age at death among those with MI and those without MI was 60.34 years (standard deviation of 13.8), and 71.51 years (standard deviation of 13.5), respectively.

Table 3.

Distribution of decedents by demographics and by cancer causes of death among those identified with mental illness and all other Ohioans

| Demographics & Cause of Death Categories | Decedents with mental illness (n=1981), % | Total Ohio (N= 101,689), % |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years: | ||

| 1–14 | 0.40 | 0.21 |

| 15–24 | 0.76 | 0.27 |

| 25–44 | 8.28 | 2.68 |

| 45–64 | 55.43 | 25.78 |

| 65+ | 35.13 | 71.06 |

| Sex: | ||

| Male | 43.97 | 51.71 |

| Female | 56.03 | 48.29 |

| Race: | ||

| Black | 20.29 | 10.09 |

| Non-Blacks | 79.71 | 89.11 |

|

| ||

| Cancer Causes of Death: | ||

| Upper gastrointestinal tract | 5.60 | 5.71 |

| Colorectal | 8.43 | 9.74 |

| Hepatobiliary | 3.13 | 2.28 |

| Pancreatic | 4.69 | 5.63 |

| Lung tissue | 34.02 | 29.76 |

| Larynx | 1.51 | 0.72 |

| Skin | 2.07 | 1.75 |

| Breast | 17.39 | 15.44 |

| Cervical and uterine | 4.41 | 4.03 |

| Ovarian | 2.88 | 4.91 |

| Prostate | 5.40 | 9.59 |

| Urinary bladder | 1.82 | 2.53 |

| Kidney and renal pelvis | 2.27 | 2.27 |

| Brain and other CNS | 2.52 | 2.17 |

| Lymphoid tissue | 7.52 | 9.74 |

| Secondary or ill defined | 6.71 | 6.47 |

| All other cancers | 3.43 | 4.46 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 |

More than half of the MI decedents were in the 45–64 age group, while the majority (71.1%) of decedents in the general population was 65 years or older. While sex distribution was about equal in the general population, there were more females (56.0%) among the MI individuals.

Blacks represented 20.29 percent and 10.09 percent of those who had MI and the general population respectively.

Among those with MI and the general population, the three leading causes of deaths were: 1) cancer of the lungs (34.0% for MI and 29.8% for the general population); 2) breast cancer (17.4% for MI and 15.4% for the general population); 3) colorectal cancer (8.43% for MI and 9.74% for the general population). These descriptive statistics are detailed in Table 3.

All-Cancer Mortality

Overall there was excess mortality from cancer associated with having MI across all of the race/sex strata. The highest age-adjusted SMR was observed in non-Black men SMR: 3.89, 95% Confidence Interval (3.61–4.19), followed by non-Black women [3.34 (3.13–3.57)], Black women [2.63 (2.31–4.19)], and Black men [2.16 (1.85–2.50)].

Site-Specific Cancer Mortality

Figures 1A-D show the cancer-specific SMRs within race/sex strata. We note statistically significant higher SMRs for every anatomic cancer site in non-Black men and women, and for most cancer sites in non-Black men and women. Failure to reach statistical significance for some cancer sites (cancer of the upper gastrointestinal tract, hepatobiliary cancer, and prostate cancer in Black men, and ovarian cancer in Black women) may have been due to small numbers.

Figure 1.

Age-Adjusted Standardized Mortality Rates (SMR) by race/sex categories

Footnote for Figures 1A–D:

- The number in parentheses indicates the observed number of observed deaths in that race/sex stratum, and for that cancer site.

- White bars are for SMRs that were not statistically significant at p < 0.05. All remaining SMRs were significant at p < 0.05.

Except among Black women, the highest SMR with statistical significance was observed for laryngeal cancer (SMR: 3.94 (1.45–8.75) in Black men, 6.51 (3.86–10.35) in non-Black men, and 6.87 (3.01–13.60) in non-Black women). In Black women, the highest SMR was noted for the kidney and renal pelvis [8.54 (4.49–14.85)]. SMRs for cancers of the urinary tract were also considerably elevated in non-Black women and men.

More than 5-fold excess mortality from hepatobiliary cancer was observed, especially in non-Black men and Black women [SMR: 5.39 (3.75–7.52) and 5.26 (2.56–9.65)], respectively

Finally, we observed elevated SMRs by 3–5 times for cancer of the lung, trachea, and bronchus (SMR: 4.33 (3.82–4.88) in non-Black men; 4.22 (3.75–4.72) in non-Black women; and 2.99 (2.33–3.78) in Black women.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to document excess mortality from cancer associated with having mental illness by differentiating the broad category of death due malignant neoplasms into specific sites of malignancies across age, gender, and racial strata. The excess cancer-related mortality among individuals with MI demonstrated striking racial variations. We believe these findings may be partially explained by known epidemiological risk factors for these specific malignancies. Beyond addressing these factors, however, these findings carry several key health care messages for this population and their health care providers, especially given the low likelihood of persons with MI to be diagnosed with early-stage disease and/or to receive guideline care (10, 27). Indeed, there seems to be insufficient awareness of medical comorbidities, leading to under-diagnosis of such conditions (28), due to the under-reporting of physical problems by the patient, the societal stigma and/or the physicians’ perception of physical complaints as psychosomatic symptoms, thus overlooking coexisting medical conditions in patients with MI (8).

The observed SMRs for laryngeal cancer are biologically plausible, given the synergistic impact of the two primary risk factors, alcohol and tobacco use (29), both of which are highly prevalent among persons with MI, and the poorer efficacy of smoking cessation and alcohol treatment programs in this population (30–31).

Compared to the general population, persons with MI carry higher prevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and alcohol and other substance abuse disorders (32), all of which are risk factors for hepatobiliary cancer. This may explain the excess mortality from hepatobiliary cancer observed in all of the race/sex strata, albeit at borderline statistical significance in Black men, due to small numbers. What remains unclear is the origin for the differences in excess hepatobiliary cancer-related mortality across the race/sex strata. Potential explanations include racial and gender differences in the prevalence of risk factors and differences in synergism between these risk factors, and competing causes of death.

Risk factors for cancers of the larynx, lung, bronchus, and trachea primarily involve direct or passive exposure to tobacco smoke. Persons with chronic MI smoke 44% of all cigarettes, reflecting both a high prevalence of use and a heavy consumption among those who do smoke (33). Thus, the observed excess mortality of respiratory tract cancers may be largely attributable to the tobacco use patterns of persons with serious MI.

While competing causes of death may be a possible explanation, the fact that excess mortality from respiratory tract cancer was not observed at a similar magnitude across race/sex strata remains puzzling. In the general population, a case control study that examined sex-race differences in the risk of lung cancer risk associated with cigarette smoking showed that for a given level of smoking, blacks were at higher risk than whites to develop lung cancer (34). Studies also further report that although African-Americans begin smoking later in life (35–36), than whites, their rates of cessation are lower, (35–37), and they use brands with higher tar yields (38–39). Given this evidence, we would have expected the excess mortality to be observed among blacks at a greater magnitude.

Excess mortality from urinary tract cancers associated with having mental illness was more accentuated in women than in men. Similar to respiratory tract malignancies, the most important risk factor associated with both kidney cancer and bladder cancer is tobacco use (40). Additional risk factors for kidney cancer include obesity, hypertension, chronic hepatitis C infection and sickle cell disease (41–42). Thus, the excess mortality associated with kidney cancer in black women with mental illness might be explained by a higher prevalence of tobacco use, obesity, hypertension, or chronic hepatitis C compared to the general population.

Results from this study should however be interpreted in light of the following limitations: First, we looked at individuals with MI in general; patterns of excess mortality may in fact differ between specific psychiatric diagnoses (43). Second, we acknowledge limitations with the accuracy of the underlying cause of death on death certificates (44). Third, we recall that individuals who were enrolled in Ohio’s publicly-funded mental health system but for whom we have no claims with a documented MI diagnosis were accounted for in the general population, rather than among those with mental illness. This approach was deemed appropriate because it was not possible to obtain person-year data on this subgroup of the population, due to how the data were captured in the state mental health agency’s information system. However, regardless of whether they actually received mental health services that were covered by the agency or through another party, this group of decedents in all likelihood indeed suffered from MI, since they were enrolled in the system. As a result, this grouping may have biased our results, at least to some extent, most likely leading to attenuated SMRs reported for those with mental illness. From an analytical standpoint, we note that compared to our previous study (45) which accounted for individuals enrolled in the publicly funded mental health system during the 4-year period for any length of time, our use of person-years in the current study yielded considerably higher SMRs.

Finally, we note that this study was of a cross-sectional nature; therefore we cannot infer a causal relationship between MI and mortality.

Conclusions

Among individuals who died of cancer, those with MI died an average of 10 years earlier than those without MI.

For many patients with MI, the psychiatrist is often the physician of first contact and may remain the only treating physician (46). Our findings support the necessity for persons with MI to have a primary care physician as well, whose focus is on preventive health care, including primary prevention and screening for early detection of disease, cancer risk assessment and screening, and health behavior assessment and counseling. Our findings also suggest a need for more intensive and coordinated efforts of the medical, behavioral, and public health systems efforts in addressing (1) smoking cessation; (2) alcohol and substance abuse prevention and treatment; and (3) screening for and treatment of chronic hepatitis. Further investigation is necessary to understand and address the observed racial variations in cancer mortality and the excess mortality from urinary tract cancers among women with MI. Ameliorating these observed disparities in cancer site-specific mortality among persons with MI will likely require interventions along the entire cancer control continuum.

Acknowledgments

Research Support:

Drs. Koroukian and Musuuza were supported by a grant from the Ohio Department of Mental Health.

Dr. Koroukian is also supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, UL1TR000439 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH

Results were presented in part at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, in Chicago, Illinois, July, 2012

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phillips Physical disorder in 164 consecutive admissions to a mental hospital:the incidence and significance. BMJ. 1934;2:363–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.3998.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamara SG, Peterson PD, Dennis JL. Prevalence of physical illness among psychiatric inpatients who die of natural causes. Psychiatr Serv. 1998 Jun;49(6):788–93. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.6.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006 Apr;3(2):A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Oct;64(10):1123–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aro S, Aro H, Keskimaki I. Socio-economic mobility among patients with schizophrenia or major affective disorder. A 17-year retrospective follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 1995 Jun;166(6):759–67. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.6.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Mental disorders and access to medical care in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1998 Dec;155(12):1775–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeste DV, Gladsjo JA, Lindamer LA, Lacro JP. Medical comorbidity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(3):413–30. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000 Jan 26;283(4):506–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.4.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baillargeon J, Kuo YF, Lin YL, Raji MA, Singh A, Goodwin JS. Effect of mental disorders on diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older adults with colon cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011 Jul;59(7):1268–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03481.x. [Comparative Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kisely S, Crowe E, Lawrence D. Cancer-Related Mortality in People With Mental Illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012 Dec;17:1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iezzoni LI, Ngo LH, Li D, Roetzheim RG, Drews RE, McCarthy EP. Treatment disparities for disabled medicare beneficiaries with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008 Apr;89(4):595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iezzoni LI, Ngo LH, Li D, Roetzheim RG, Drews RE, McCarthy EP. Early stage breast cancer treatments for younger Medicare beneficiaries with different disabilities. Health Serv Res. 2008 Oct;43(5 Pt 1):1752–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batty GD, Whitley E, Gale CR, Osborn D, Tynelius P, Rasmussen F. Impact of mental health problems on case fatality in male cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2012 May 22;106(11):1842–5. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowersox NW, Kilbourne AM, Abraham KM, Reck BH, Lai Z, Bohnert AS, et al. Cause-specific mortality among Veterans with serious mental illness lost to follow-up. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012 Nov-Dec;34(6):651–3. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Avanzo B, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Mortality in long-stay patients from psychiatric hospitals in Italy--results from the Qualyop Project. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003 Jul;38(7):385–9. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0646-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valenti M, Necozione S, Busellu G, Borrelli G, Lepore AR, Madonna R, et al. Mortality in psychiatric hospital patients: a cohort analysis of prognostic factors. Int J Epidemiol. 1997 Dec;26(6):1227–35. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.6.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guan NC, Termorshuizen F, Laan W, Smeets HM, Zainal NZ, Kahn RS, et al. Cancer mortality in patients with psychiatric diagnoses: a higher hazard of cancer death does not lead to a higher cumulative risk of dying from cancer. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012 Oct 27; doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0612-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ODMH. Ohio Department of Mental Health Who We Are. 2010 [cited 2012 Jan 5]; Available from: http://mentalhealth.ohio.gov/who-we-are/

- 20.Koroukian SM, Beaird H, Duldner JE, Diaz M. Analysis of injury-and violence-related fatalities in the Ohio Medicaid population: identifying opportunities for prevention. J Trauma. 2007 Apr;62(4):989–95. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000210359.98816.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koroukian SM, Cooper GS, Rimm AA. Ability of Medicaid claimsdata to identify incident cases of breast cancer in the Ohio Medicaid population. Health Serv Res. 2003 Jun;38(3):947–60. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koroukian SM. Linking the Ohio Cancer Incidence System with Medicare, Medicaid and clinical data from home health care and long term care assessment instruments: Paving the way for new research endeavors in geriatric onocology. Journal of Registry Management. 2008;35(4):156–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U. S. National Institutes of Health NCI. SEER Training Modules, Site-specific Modules. U. S. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; [cited 2011 Jan 6]; Available from: http://training.seer.cancer.gov/modules_site_spec.html. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Center for Health Statistics. Deaths: Final Data for 2007. Hyattsville: [cited 2011 Jan 6]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_19.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emory University School of Public Health. OpenEpi-Confidence intervals for SMR. Atlanta: [cited 2012 Jan 8]; Available from: http://www.sph.emory.edu/~cdckms/exact-midP-SMR.html. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawrence D, Kisely S. Review: Inequalities in healthcare provision for people with severe mental illness. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2010 Nov 1;24(4 suppl):61–8. doi: 10.1177/1359786810382058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeste DV, Gladsjo JA, Lindamer LA, Lacro JP. Medical Comorbidity in Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1996 Jan 1;22(3):413–30. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pelucchi C, Gallus S, Garavello W, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C. Alcohol and tobacco use, and cancer risk for upper aerodigestive tract and liver. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2008;17(4):340–4. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75e91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Compton WM, 3rd, Cottler LB, Jacobs JL, Ben-Abdallah A, Spitznagel EL. The role of psychiatric disorders in predicting drug dependence treatment outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 May;160(5):890–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mackowick KM, Lynch MJ, Weinberger AH, George TP. Treatment of tobacco dependence in people with mental health and addictive disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012 Oct;14(5):478–85. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0299-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, Swartz MS, Essock SM, Butterfield MI, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001 Jan;91(1):31–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schroeder SA, Morris CD. Confronting a Neglected Epidemic: Tobacco Cessation for Persons with Mental Illnesses and Substance Abuse Problems. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31(1):297–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris RE, Zang EA, Anderson JI, Wynder EL. Race and sex differences in lung cancer risk associated with cigarette smoking. Int J Epidemiol. 1993 Aug;22(4):592–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King G. The “race” concept in smoking: a review of the research on African Americans. Soc Sci Med. 1997 Oct;45(7):1075–87. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson TL. African-American smokers and cancers of the lung and of the upper respiratory and digestive tracts. Is menthol part of the puzzle? West J Med. 1997 Mar;166(3):189–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Botvin GJ, Baker E, Botvin EM, Dusenbury L, Cardwell J, Diaz T. Factors promoting cigarette smoking among black youth: a causal modeling approach. Addict Behav. 1993 Jul-Aug;18(4):397–405. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90056-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez-Stable EJ, Herrera B, Jacob P, 3rd, Benowitz NL. Nicotine metabolism and intake in black and white smokers. JAMA. 1998 Jul 8;280(2):152–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zang EA, Wynder EL. Smoking trends in the United States between 1969 and 1995 based on patients hospitalized with non-smoking-related diseases. Prev Med. 1998 Nov-Dec;27(6):854–61. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunt JD, van der Hel OL, McMillan GP, Boffetta P, Brennan P. Renal cell carcinoma in relation to cigarette smoking: Meta-analysis of 24 studies. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;114(1):101–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chow W-H, Gridley G, Fraumeni JF, Järvholm B. Obesity, Hypertension, and the Risk of Kidney Cancer in Men. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343(18):1305–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011023431804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pischon T, Lahmann PH, Boeing H, Tjønneland A, Halkjær J, Overvad K, et al. Body size and risk of renal cell carcinoma in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) International Journal of Cancer. 2006;118(3):728–38. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joukamaa M, Heliovaara M, Knekt P, Aromaa A, Raitasalo R, Lehtinen V. Mental disorders and cause-specific mortality. Br J Psychiatry. 2001 Dec;179:498–502. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.6.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Modelmog D, Rahlenbeck S, Trichopoulos D. Accuracy of death certificates: a population-based, complete-coverage, one-year autopsy study in East Germany. Cancer Causes Control. 1992 Nov;3(6):541–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00052751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherman ME, Knudsen KJ, HelenAnne Sweeney, Tam K, Musuuza J, Koroukian SM. Analysis of Causes of Death for All Decedents in Ohio With and Without Mental Illness, 2004 – 2007. Psychiatric Services. 2013 Jan; doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100238. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson DA. The evaluation of routine physical examination in psychiatric cases. Practitioner. 1968 May;200(199):686–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]