Abstract

Background

Hospital infection control strategies and programs may not consider control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in nursing homes in a county.

Methods

Using our Regional Healthcare Ecosystem Analyst (RHEA), we augmented our existing agent-based model of all hospitals in Orange County (OC), California, by adding all nursing homes and then simulated MRSA outbreaks in various healthcare facilities.

Results

The addition of nursing homes substantially changed MRSA transmission dynamics throughout the County. The presence of nursing homes substantially potentiated the effects of hospital outbreaks on other hospitals, leading to an average 46.2% (range: 3.3–156.1%) relative increase above and beyond the impact when only hospitals are included for an outbreak in OC’s largest hospital. An outbreak in the largest hospital affected all other hospitals (average 2.1% relative prevalence increase) and the majority (~90%) of nursing homes (average 3.2% relative increase) after six months. An outbreak in the largest nursing home had effects on multiple OC hospitals, increasing MRSA prevalence in directly connected hospitals by an average 0.3% and in hospitals not directly connected via patient transfers by an average 0.1% after six months. A nursing home outbreak also had some effect on MRSA prevalence in other nursing homes.

Conclusions

Nursing homes, even those not connected by direct patient transfers, may be a vital component of a hospital’s infection control strategy. To achieve effective control, a hospital may want to better understand how regional nursing homes and hospitals are connected via both direct and indirect (with intervening stays at home) patient sharing.

Keywords: MRSA, Outbreak, Long-term Care, Nursing Homes, Hospitals

INTRODUCTION

Individual hospitals or hospital systems may not consider nursing homes when planning their infection control strategies. However, our previous work has shown that hospitals and nursing homes in a region may be highly interconnected by patient sharing(1–2). Patients often move among various hospitals and nursing homes either via direct transfers or with intervening stays at home(1, 3–5), and in some instances repeatedly(6–7). Moreover, nursing homes are important reservoirs of multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs), especially methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)(8–9), which tends to be more prevalent (20–50%) in many long-term care settings(9–13)than in acute care hospitals (5–10%)(14–16). Many questions remain. How might an MRSA outbreak in one hospital affect that of a nursing home and vice versa? Should hospitals and nursing homes work together to reduce MDROs? While previous mathematical and computational models have explored MRSA spread among just hospitals(17–20), a single nursing home(21), or a small group of closely associated nursing homes and hospitals that directly transfer patients to one another(22), these studies did not examine all of the inpatient facilities in a large real-life region. One study modeled hospitals and nursing homes in a region of Canada (which has a different healthcare system)(23). With facilities connected via patient sharing over considerable distances in a very complex manner through both direct and indirect patient sharing, predicting the effects of an outbreak in a single facility may be difficult since a variety of sources and sinks may emerge.

METHODS

General Model Structure and Data Sources

We expanded our previously described agent-based model (ABM), generated by our custom-designed software, the Regional Healthcare Ecosystem Analyst (RHEA)(17), of all adult acute care facilities to add all 71 nursing homes (providing post-acute or long-term care) in Orange County, CA. The RHEA-created model simulated the movement of virtual patients (i.e., computational agents) to and from the community into and between healthcare facilities, and MRSA spread. We used 2007 patient-level data for all adult inpatient admissions from 100 total facilities (29 hospitals and 71 nursing homes). Data came from several sources, including a state mandatory hospitalization dataset, a national long-term care dataset (Minimum Data Set), and hospital and nursing home surveys conducted from 2006–2008 to assess the distribution of transferring locations (e.g., specific hospitals, specific nursing homes, rehabilitation centers, assisted living facilities, home) of patients admitted to and discharged from each facility during a consecutive 12-month period(24–27). Data on facility MRSA prevalence came from regional surveys and patient screenings(12, 26). Table 1 shows our model inputs and characteristics for the OC healthcare facilities.

Table 1.

Hospital and nursing home characteristics and model input parameters

| Hospitals | Nursing Homes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (Range) | Mean (SD) | Median (Range) | |

| Annual Adult Admissions | 8,826.7 (6,780.5) | 7,033 (425 – 27,151) | 504.5 (862.6) | 311 (3 – 7,080) |

| Licensed Beds | 228.6 (120.2) | 194 (48 – 505) | 108.6 (58.0) | 99 (9 – 300) |

| Average Daily Census | 131 (90) | 103 (16 – 368) | 86.7 (43.2) | 85.3 (9 – 214) |

| Length of Stay (days)a | 5.4 (7.6) | 4 (1 – 626) | 210.5 (447.4) | 37 (1 – 5,066) |

| MRSA Prevalence | 6.1 (5.4) | 3.4 (1.1 – 18.5) | 26.1 (8.6) | 25.9 (0 – 52) |

| Transmission Coefficient (β) | 0.0099 (0.0402) | 0.0017 (0 – 0.2966) | 0.000082 (0.000056) | 0.000068 (0 – 0.00030) |

| Length of Stay for MRSA-positive Patientsb | 12 (16.1) | 8 (1 – 414) | - | - |

| Number of Discharges to Community | 4,598.6 (4,075.6) | 2,699 (134 – 16,541) | 378.7 (311.4) | 333 (17 – 1,172) |

| Number of Direct Transfers to Hospitals | 91.3 (58.9) | 80 (17 – 261) | 74.0 (66.4) | 58 (0 – 261) |

| Number of Direct Transfers to Nursing Homes | 806.1 (666.3) | 679 (38.5 – 2,616) | 10.5 (10.9) | 8 (0 – 64) |

| Number of Hospital Readmissions | 2,401.1 (1,880.7) | 1,810 (82 – 7,178) | 354.2 (332.4) | 249 (19 – 1,403) |

| Time to Readmission (Length of Stay in Holding Bin)b | 93.9 (100.6) | 52 (1 – 366) | 90 (96.2) | 50 (1 – 366) |

| Number of Temporary Discharges to Hospitals | - | - | 291.5 (224) | 248 (0 – 1,584) |

| Length of Temporary Hospital Stayc | - | - | 5.8 (6.1) | 5 (0 – 14) |

Hospitals pull from a lognormal distribution; nursing homes pull from line-item data

Pulled from a lognormal distribution

Pulled from line-item data

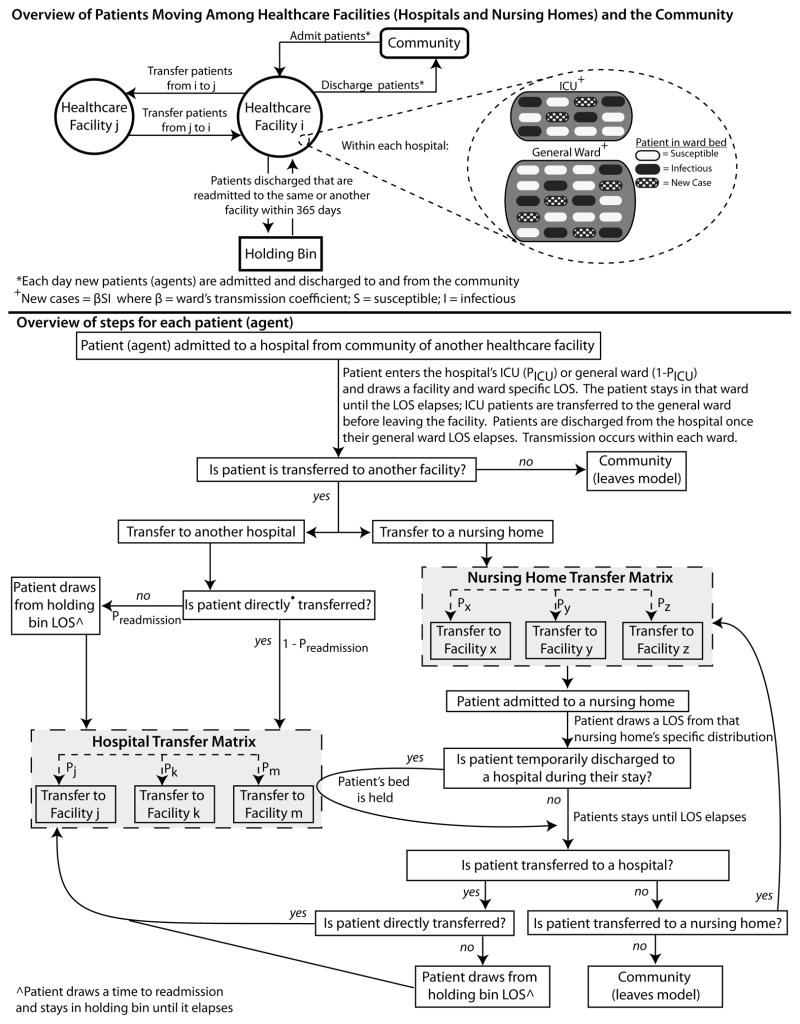

Appendix 1 illustrates how patients move in the model. When a patient (either MRSA-carrier or non-carrier) is admitted to a hospital, he/she can enter either a general ward, or an intensive care unit (ICU), if present in the facility, and stay there for a length of stay (LOS) drawn from a distribution specific to that facility and ward. Patients mix homogeneously with other patients within the same ward but not across wards. Based upon actual facility-specific data, the LOS distribution for MRSA-positive patients is longer (average 5 days longer county-wide) than that of MRSA-negative patients(24). Patients discharged from hospitals can return to the community, directly transfer to another OC facility (either hospital or nursing home), or return home to later return to the same or another hospital based on facility-specific probabilities derived from actual patient data(25).

Appendix 1.

While each hospital included multiple wards and units, each nursing home consisted of a single homogeneously mixing ward to represent a high degree of social interactions (e.g., group activities). Patients entering a nursing home drew a LOS from that facility’s distribution. Once a nursing home resident’s total LOS elapsed, he/she could move to the community, a hospital, or another nursing home. A fraction of those returning to the community were readmitted according to known regional readmission data(25).

During a nursing home stay, a patient could also experience brief hospitalizations, during which the patient’s bed was “held” for his/her return. Nursing home residents with a LOS ≥ 14 days had a daily probability of brief readmission to a hospital (based on nursing home-specific frequencies for temporary discharges). The patient has probabilities of going to particular hospitals (for a LOS drawn from data of known temporary hospitalizations) from that nursing home (based on nursing home-specific data).

Sixty-one (85%) countywide nursing homes provided detailed distributions of patients’ locations before and after their stay. When combined with hospital survey data about admissions and discharges to and from nursing homes (27 hospitals, 93% participation), comprehensive transfer probabilities between hospitals and nursing homes as well as between nursing homes were compiled and used as model inputs. Three nursing homes had limited data and were not included in the analysis.

MRSA Transmission within Facilities

Each day in each ward in each facility, the following formula governed the number of new MRSA cases:

where β is the transmission coefficient, S is the number of susceptible patients, and I is the number of colonized patients. Influx of MRSA carriers at hospitals reflected survey-reported prevalence and β was parameterized to produce an incidence of 1% in general wards and 3% in ICUs(17). For nursing homes, MRSA influx and transmission was based upon actual admission prevalence data and point prevalence screenings from 40% of nursing homes (having a mean 16% acquisition risk(28)). For those not sampled, estimated importation and transmission were extrapolated from generalized linear mixed models estimating carriage risk and incident disease based upon facility-level risk factors, including case mix. Therefore, the ward and facility specific β accounted for differences in MRSA susceptibility among patients in different facilities and transmission via staff members. Our model did not have separate β’s for patients with active MRSA infections (vs. asymptomatic carrier) based on evidence that suggest no difference(29).

MRSA-positive patients could lose MRSA carriage over time(30–33); one-third had indefinite carriage(34) and the remainder experienced a linear carriage loss with a half-life of six months(30, 33).

Experimental Scenarios

Different experimental scenarios simulated sustained (to estimate the potential maximal effect) and temporary (i.e., six month) MRSA outbreaks in selected hospitals and nursing homes: an absolute increase in MRSA prevalence of 10% in hospitals and 20% in nursing homes. We specifically simulated outbreaks in facilities that may have a high likelihood of experiencing an outbreak (because of their high volume and extensive patient sharing): the two largest hospitals and nursing homes by annual admissions, as well as the two hospitals and nursing homes sending the most number of patients to one facility of the opposite type (i.e., the hospital sending the largest number of patients to one nursing home). For each outbreak, we assessed the impact on all hospitals and nursing homes in OC, individually and countywide. We compared experiments with and without simulated outbreaks to assess the attributable change in MRSA prevalence due to the outbreak and the number of excess MRSA carriers generated for each scenario across the entire county and in all other facilities. Additional experiments varied the outbreak size from 10%, 20%, and 30%. For each scenario, we averaged the results from 25,000 simulations for each facility. The percent relative increase in MRSA prevalence was measured for each facility and countywide averages are presented.

RESULTS

Outbreak in a Single Hospital

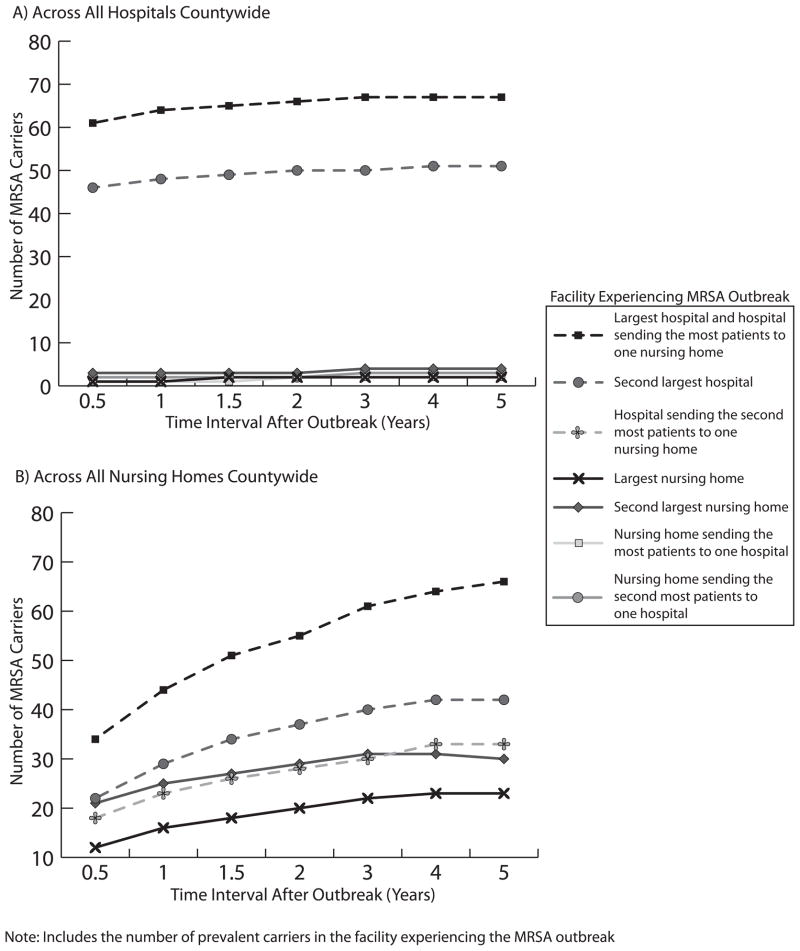

Adding nursing homes to the model substantially changed the dynamics of MRSA spread throughout the county. The presence of nursing homes substantially potentiated the effects of a hospital outbreak on other hospitals, leading to an average relative increase of 46.2% (range: 3.3% to 156.1%) above and beyond the impact when only hospitals are included for an outbreak in OC’s largest hospital. The top half of Table 2 shows how hospital outbreaks affected the MRSA prevalence in other hospitals over time in the full model with all OC inpatient healthcare facilities. (The standard deviation for each of the results in Table 2 ranged from 0.00041 to 0.0049.) Table 2 provides the mean, median, interquartile range, and total range of effects. The effects on other facilities were fairly heterogeneous (i.e., different facilities have different effects from the outbreak). Figure 1 shows the increase in daily number of MRSA carriers from each outbreak.

Table 2.

Percent relative increase in MRSA prevalence in all other OC hospitals and nursing homes at different time points after a sustained MRSA outbreak in various OC healthcare facilities

| Facility Experiencing MRSA Outbreak | Time After Outbreak (Years)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Percent Relative MRSA Prevalence Increase in OC Hospitals | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Hospital Outbreaks | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Largest hospital | Mean (Range) | 2.1 (NE, 8.0) | 2.5 (NE, 8.9) | 2.7 (NE, 9.6) | 2.9 (NE, 10.2) | 2.9 (NE, 11.6) | 3.0 (NE, 10.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.1 (0.8, 2.7) | 1.9 (1.3, 3.7) | 1.3 (1.0, 3.4) | 1.8 (1.4, 3.9) | 1.8 (1.4, 3.8) | 2.1 (1.5, 4.0) | |

|

| |||||||

| Second largest hospital | Mean (Range) | 2.6 (0.2, 33.2) | 3.0 (0.2, 37.4) | 3.2 (0.3, 40.3) | 3.5 (0.6, 41.5) | 3.5 (NE, 41.6) | 3.5 (NE, 41.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.2 (0.7, 1.9) | 1.6 (0.9, 1.9) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.4) | 1.7 (1.4, 2.3) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.4) | 1.7 (1.4, 2.6) | |

| Nursing Home Outbreaks | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Largest nursing home | Mean (Range) | 0.2 (NE, 1.4) | 0.2 (NE, 2.4) | 0.3 (NE, 2.6) | 0.4 (NE, 2.4) | 0.4 (NE, 2.9) | 0.4 (NE, 2.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.2 (0, 0.3) | 0.2 (NE, 0.4) | 0.2 (0, 0.4) | 0.2 (0, 0.4) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.4) | 0.3 (NE, 0.6) | |

|

| |||||||

| Second largest nursing home | Mean (Range) | 0.5 (NE, 5.1) | 0.5 (NE, 6.2) | 0.6 (NE, 6.8) | 0.7 (NE, 6.7) | 0.7 (NE, 7.2) | 0.7 (NE, 6.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.2 (NE, 0.3) | 0.1 (NE, 0.4) | 0.2 (NE, 0.4) | 0.2 (0, 0.5) | 0.1 (0, 0.5) | 0.1 (0, 0.6) | |

|

| |||||||

| Nursing home sending the most patients to one hospital | Mean (Range) | 0.1 (NE, 1.9) | 0.1 (NE, 2.8) | 0.1 (NE, 3.8) | 0.3 (NE, 4.0) | 0.2 (NE, 4.6) | 0.3 (NE, 4.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (NE, 0.1) | 0 (NE, 0.2) | NE (NE, 0.1) | 0.1 (NE, 0.2) | 0.1 (NE, 0.2) | 0.1 (NE, 0.2) | |

|

| |||||||

| Nursing home sending the second most patients to one hospital | Mean (Range) | 0.2 (NE, 4.6) | 0.3 (NE, 5.9) | 0.3 (NE, 6.5) | 0.5 (NE, 7.0) | 0.5 (NE, 7.3) | 0.4 (NE, 7.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (NE, 0.2) | 0 (NE, 0.2) | 0.1 (NE, 0.3) | 0.1 (NE, 0.3) | 0.1 (NE, 0.3) | 0.1 (NE, 0.3) | |

|

| |||||||

| Percent Relative MRSA Prevalence Increase in OC Nursing Homes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Hospital Outbreaks | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Largest hospital and hospital sending the most patients to one nursing home | Mean (Range) | 3.2 (NE, 60.8) | 4.0 (NE, 75.9) | 4.6 (NE, 83.9) | 4.9 (NE, 89.4) | 5.2 (NE, 96.1) | 5.3 (NE, 98.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.3, 2.4) | 1.2 (0.3, 3.1) | 1.0 (0.3, 2.5) | 1.2 (0.4, 3.3) | 1.3 (0.3, 3.6) | 1.4 (0.6, 3.9) | |

|

| |||||||

| Second largest hospital | Mean (Range) | 1.5 (NE, 25.7) | 1.9 (NE, 34.2) | 2.2 (NE, 38.7) | 2.4 (NE, 42.5) | 2.5 (NE, 46.2) | 2.6 (NE, 48.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.4 (0.2, 1.0) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.1) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.4) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.7) | 0.9 (0.4, 1.8) | 1.0 (0.5, 2.1) | |

|

| |||||||

| Hospital sending the second most patients to one nursing home | Mean (Range) | 1.7 (NE, 21.6) | 2.1 (NE, 25.2) | 2.3 (NE, 27.3) | 2.5 (NE, 30.5) | 2.6 (NE, 35.1) | 2.7 (NE, 38.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.4 (0, 0.8) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) | 0.2 (0, 0.9) | 0.3 (NE, 0.8) | 0.3 (NE, 1.0) | 0 (NE, 0.2) | |

|

| |||||||

| Nursing Home Outbreaks | |||||||

| Largest nursing home | Mean (Range) | 0.1 (NE, 1.2) | 0.1 (NE, 1.9) | 0.1 (NE, 2.1) | 0.2 (NE, 2.3) | 0.2 (NE, 3.1) | 0.2 (NE, 3.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.1 (NE, 0.2) | 0.1 (NE, 0.3) | 0.1 (NE, 0.3) | 0.1 (NE, 0.3) | 0.1 (0, 0.4) | 0.2 (0, 0.4) | |

|

| |||||||

| Second largest nursing home | Mean (Range) | 0.0 (NE, 0.7) | 0.1 (NE, 1.2) | 0.1 (NE, 1.1) | 0.1 (NE, 1.0) | 0.1 (NE, 1.4) | 0.2 (NE, 1.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (NE, 0.2) | 0.1 (NE, 0.3) | 0 (NE, 0.3) | 0.1 (0, 0.3) | 0.1 (0, 0.3) | 0.1 (0, 0.3) | |

NOTE: NE = no effect; Change in non-outbreak facilities only;

Figure 1.

Average increase in daily number of MRSA carriers in Orange County after sustained MRSA outbreaks A) across all hospitals countywide, B) across all nursing homes countywide

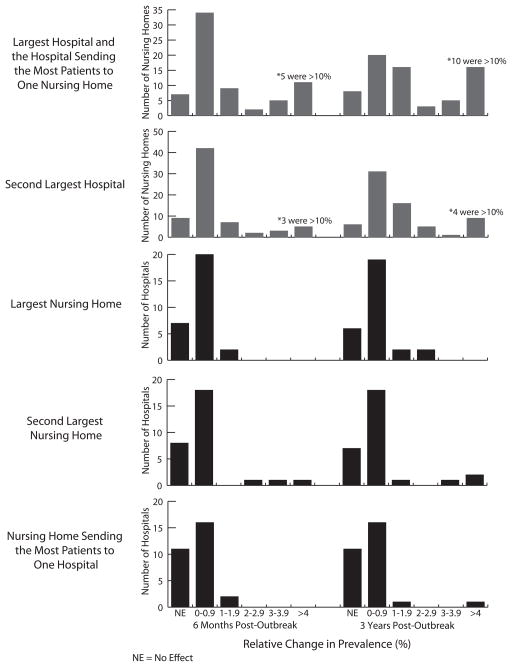

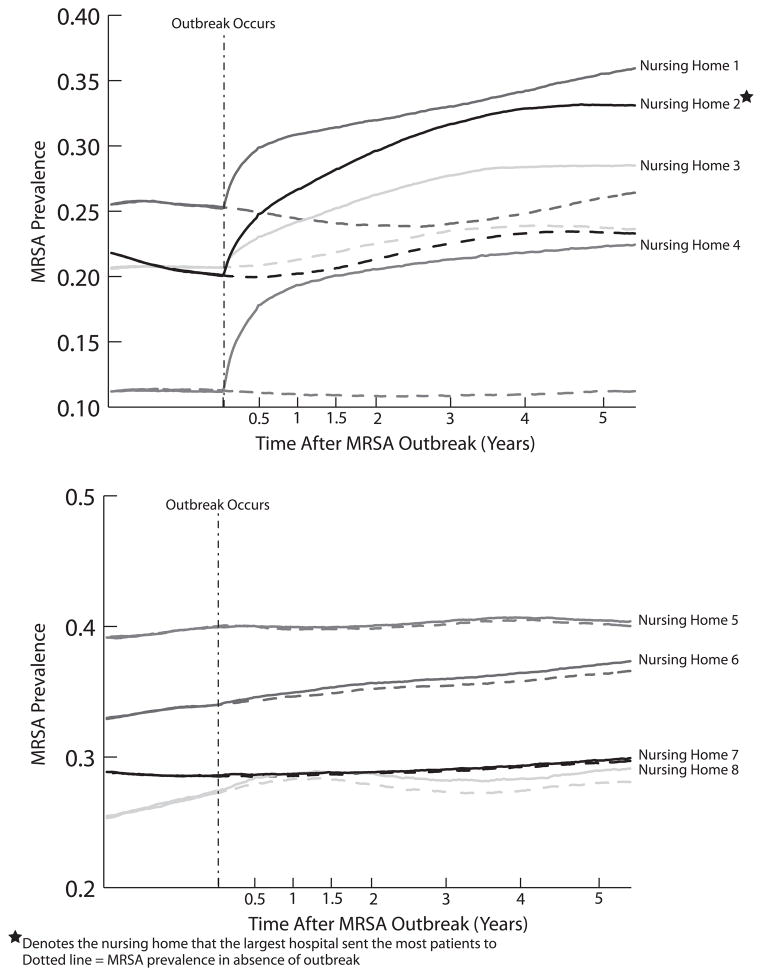

The bottom half of Table 2 shows the effects of single hospital outbreaks on nursing home MRSA prevalence over time. Figure 2 shows the number of nursing homes experiencing a given relative change in prevalence when the largest and second largest hospitals experienced an outbreak. Outbreak effects took time to manifest, with many nursing homes experiencing changes >4%. Figure 3 compares the resulting MRSA prevalence in select OC nursing homes (exemplifying large, moderate, and small effects) when an outbreak occurs in the largest hospital (also, the one sending the most patients to one nursing home) versus no hospital outbreak.

Figure 2.

Relative increases in MRSA prevalence and number of facilities experiencing this increase at six months and three years post-outbreak in various OC healthcare facility sustained outbreaks

Figure 3.

Effects of MRSA prevalence increases in the largest hospital on nursing homes experiencing large, moderate, and small prevalence increases over time

Table 2 also shows what happened when an outbreak occurred in the two hospitals sending the most patients to one nursing home (1,063 patients and 752 patients to two different nursing homes over the course of a year, respectively); those nursing homes saw a 24.4% and 13.5% relative MRSA prevalence increase six months post-outbreak. However, the nursing homes manifesting the highest relative prevalence changes were not the ones who directly received the most patients.

Increasing the MRSA outbreak size (20% – 30% absolute increase) in hospitals increased the relative change and number of nursing homes affected. For example, six months post-outbreak, a 20% outbreak in the largest hospital affected 61 nursing homes, with 18 experiencing ≥4% increase (5.6% average relative increase in prevalence in nursing homes), while a 30% outbreak affected 65 nursing homes (7.7% relative MRSA prevalence increase).

Outbreak in a Single Nursing Home

Table 2 also shows the results of outbreaks in a single nursing home (again, the standard deviation for each of these results ranged from 0.00041 to 0.0049). An outbreak in a single nursing home also notably (albeit less in magnitude than a single hospital outbreak) affected multiple facilities. Figure 1 shows the increase in the daily number of MRSA carriers and Figure 2 shows the number of hospitals experiencing a given relative change in prevalence as a result of a nursing home outbreak.

As Figure 2 and Table 2 show, the second largest nursing home had a greater impact than an outbreak in the largest or the most connected nursing home, generating 12 new MRSA conversions within a year in all other facilities. This highlights the potential impact of other factors such as length of stay and mixing patterns (as reflected in the transmission coefficient).

Outbreaks in nursing homes tended to most affect the hospital to which they sent the largest number of patients. The outbreak in the nursing home sending the most patients to one hospital had the largest effect on that hospital (1.9% relative prevalence increase after six months), while it had little effect on the other hospitals (Figure 2). Similarly, an outbreak in the nursing home sending the second most patients to one hospital caused a 4.6% relative increase in prevalence in that hospital within six months and 7.0% relative increase in prevalence within two years.

Varying the outbreak size varied the number and magnitude of change in MRSA prevalence in OC hospitals. For example, for the second largest nursing home, a 10% absolute MRSA outbreak affected 14 hospitals, while a 30% absolute outbreak affected 21 hospitals (relative change in prevalence >0%) after one year.

Nursing home MRSA outbreaks did have some effects on other OC nursing homes. Very few experienced relative MRSA prevalence increases of ≥ 1%. Even among those experiencing increases, effects took longer to manifest (Table 2). Two years after an outbreak in the largest nursing home, 66 others experienced <1% increase and 23 no effect, for an average 0.2% relative increase (Table 2). Four years later, 62 nursing homes showed <1% increase and 20 no effect.

Other OC nursing homes were still affected with smaller MRSA outbreaks in a nursing home; 37 saw a relative prevalence increase >0% when the second largest nursing home had a 10% MRSA outbreak. For a larger outbreak (30% absolute increase), 42 other OC nursing homes had a change >0%.

Impact of Six Month Outbreaks

A six month outbreak in the largest hospital showed maximum effects in all other OC facilities six months post-outbreak for an average relative 2.4% increase in MRSA prevalence (range: no effect to 36.4%); four nursing homes experienced a ≥10% prevalence increase. While effects steadily decreased after the outbreak concluded, MRSA prevalence in affected facilities did not return to pre-outbreak levels until four years later. A short outbreak in the second largest nursing home resulted in a relative prevalence increase of 0.1% (range: no effect to 4.5%) in all other OC healthcare facilities six month post-outbreak (16 hospitals were affected, of which 3 were ≥2%). These affects dwindled within one year.

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that to fully understand the spread and control of an infectious pathogen such as MRSA, one must consider how all of the inpatient facilities (both hospitals and nursing homes) in a large geographic region are connected by both direct and indirect patient sharing. However, many hospital infection control efforts focus exclusively on hospitals. Even existing multi-institutional collaboratives tend to exclude nursing homes(35–37). Hospital infection control efforts that do include nursing homes tend to only include a few nursing homes that receive or send a substantial number of direct transfers (e.g., strong fiscal/administrative ties with the hospital). Despite their much smaller size and less frequent turnover compared to hospitals, the impact of nursing homes is substantial and reaches across many miles. This may be due in part to the relatively high prevalence of MRSA in nursing homes, averaging 25% in OC(12, 38), consistent with published literature(11–12, 39–42). MRSA acquisition has substantial sequelae(43); MRSA-positive nursing home residents have a 10% risk of MRSA infection within the first month of arrival, with risks as high as 40% within one year(41–42, 44). These infections are costly and often result in hospital readmission(41, 45–46). Of patients hospitalized with MRSA infection, 20–40% were recently in nursing homes(43, 47–48).

Nursing homes can influence hospital infection control by several means. First, nursing homes can multiply/magnify the effects of a hospital outbreak on other hospitals. The close quarters, heavy social mixing, and already high prevalence of MRSA in nursing homes can “fuel” a hospital MRSA outbreak by serving a “cauldron” of transmission, multiplying the number of cases and then sending them to hospitals throughout the County. A nursing home can link two hospitals that were not otherwise strongly linked, acting as a bridge for infectious pathogens to spread from facility to facility. Secondly, outbreaks originating a nursing home can affect multiple hospitals in a region, even those geographically distant. Even if a hospital keeps its own MRSA levels low, it is at risk for an outbreak if nursing homes in the same region do not maintain effective infection control. Third, when an outbreak occurs, determining the original culprit can be challenging. The result of an outbreak in a single hospital or nursing home could appear like multiple outbreaks in many different facilities. Different facilities may rush to control their “outbreaks” without uncovering the true origin, leading to a fruitless chase. Our study did not even consider outbreaks originating concurrently in more than one facility, which could very readily occur in such a large region with so many people (OC has a population of 3.1 million and is the 6th largest US County). Such concurrent outbreaks could produce even more synergistic transmission effects, potentially turning a smaller controllable outbreak into one much more difficult to control. One could envision an outbreak in a community served by multiple facilities leading to such an eventuality (17).

Previously published models may not fully capture these effects. Hospital only models(17–20) miss key nursing home reservoirs. A literature search found two models that included both hospitals and nursing homes. Barnes et al. constructed a theoretical mathematical model comprised of a single generic hospital and two connected nursing homes(22). Their model suggested that hospitals can affect MRSA prevalence in a nursing home, but transferring patients from a nursing home to a hospital would have a negligible effect on MRSA prevalence in that hospital unless patients are consistently transferred to the same unit in that hospital. Lesosky et al. constructed a stochastic discrete-time Monte Carlo simulation comprised of teaching hospitals, non-teaching hospitals, and nursing homes(23). Their model only focused on MRSA acquisition rate, but suggested transfer patterns and rate changes do not affect MRSA transmission. Our study, which includes many more nursing homes and hospitals and their complex connections, suggests otherwise: nursing homes do not have to transfer patients to the same unit of hospital to affect the hospital (in our model patients went from nursing homes to many different wards/units in many different hospitals) and transfer patterns and rate changes may be key drivers of MRSA transmission (an outbreak in a nursing home has heterogeneous effects on hospitals). The differing findings likely emerge from three considerable differences from our model. First, the Barnes and Lesosky models are theoretical and simplified; one assumes uniform characteristics for each of the facility types and the other does not model actual facilities. By contrast, our model uses extensive and detailed real-world data, (e.g., parameterized with facility-specific admission volume, ICU volume, bed capacity, LOS, and transfer probabilities MRSA carriage, and transmission). Second, our model included a much larger geographic region and all of their inpatient facilities. Third, our model accounted for both direct and indirect patient sharing among facilities. Our previous work showed that excluding indirect patient sharing (i.e., patient movement from facility to facility with an intervening stay in the community) neglects the majority of patient sharing(1–2) and in turn MRSA transmission routes.

The difference between prior models and our models can serve a lesson for infection control. Not considering nursing homes, true connections based on real world data among hospitals and nursing homes, all of the facilities in a region, and indirect patient sharing could limit the understanding and implementation of infection control. Even if adequate control is maintained in all hospitals, a single nursing home with poor MRSA control can affect multiple facilities. Understanding drivers and mitigators of pathogen spread in nursing homes is urgently needed as the Department of Health and Human Services has named nursing homes the focus of Phase 3 of its Action Plan to reduce healthcare-associated infections.

Limitations

Our model may underestimate the amount of MRSA in nursing homes as we assumed that MRSA-positive nursing home residents lost MRSA carriage at the same rate as hospitalized patients (i.e., six month half life), where in fact carriage may persist for several years in these settings(32, 49). In addition, homogeneous mixing may potentially overestimate the actual contact rate.

By definition, all models are simplifications of real life and as such cannot represent every possible outcome or event(50). Our model does not include co-morbidities that may affect MRSA transmission, but its admission and re-admission rates in nursing homes and hospitals reflect the health status of this California region. We did not include emergency departments, which could have a potential impact, as inpatients were the scope of this study. Additionally, our model does not include pediatric hospitalizations or account for the effect on healthcare facilities outside of OC. Nevertheless, since pediatric patients uncommonly mix with adult patients during hospitalizations or nursing home care and since, the vast majority of hospitalized adults remain within OC facilities (≥83.4% for all types of patient transfers); this model is a reasonable representation for adult transmission of MRSA. OC may not be representative of all counties or regions. However, similar findings may apply regions similar to OC, i.e., metropolitan counties with multiple facilities and health care systems.

Conclusions

Nursing homes may play an important role in the spread and control of infectious pathogens like MRSA. Nursing homes may multiply the effects of a hospital outbreak, originate outbreaks that in turn affect multiple hospitals, and make it even more difficult to trace the source of an outbreak. Even if hospitals maintain effective infection control, even a single nursing home with poor infection control can lead to hospital outbreaks. These findings have several implications for hospital infection control. Hospitals should consider and even include nursing homes in their infection control measures. Hospitals should better understand the true (based on real-world data) connections among other hospitals and nursing homes in their County/region via patient sharing. These connections should include both direct and indirect patient sharing. There may be benefit in applying to nursing homes the same rigor in infection control seen in many hospitals. Ultimately, controlling MRSA and other MDROs may necessitate close collaboration among hospitals and nursing homes across financial and administrative relationships.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Models of Infectious Disease Agent Study (MIDAS) grants 5U54GM088491-02 and 1U01GM076672 and the Pennsylvania Department of Health. This project was also funded under Contract No. HHSA29020050033I from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services as part of the Developing Evidence to Inform Decisions about Effectiveness (DEcIDE) program. The authors of this report are responsible for its content. Statements in the report should not be construed as endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Computational resources were provided by the Center for Simulation and Modeling.

References

- 1.Lee BY, Song Y, Bartsch SM, et al. Long-term care facilities: important participants of the acute care facility social network? PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e29342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee BY, McGlone SM, Song Y, et al. Social network analysis of patient sharing among hospitals in Orange County, California. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:707–13. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.202754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buntin MB. Access to postacute rehabilitation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabiliation. 2007;88:1488–93. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konetzka RT, Spector W, Limcanqco MR. Reducing hospitalizations from long-term care settings. Medical Care Research and Reveiw. 2008;65(1):40–66. doi: 10.1177/1077558707307569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith PW, Bennet G, Bradley SF, et al. SHEA/APIC guideline: infection prevention and control in the long-term care facility. American Journal of Infection Control. 2008;36:504–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, et al. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 Jan-Feb;29(1):57–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouslander JG, Diaz S, Hain D, et al. Frequency and diagnoses associated with 7-and 30-day readmission of skilled nursing facility patients to a nonteaching community hospital. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2011 Mar;12(3):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rebmann T, Aureden K. Preventing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission in long-term care facilities: an executive summary of the APIC elimination guide. American Journal of Infection Control. 2011;39:235–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone ND, Lewis DR, Lowery HK, et al. Importance of bacterial burden among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriers in a long-term care facility. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2008;29(2):143–8. doi: 10.1086/526437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mermel LA, Eells S, Acharya MK, et al. Quantitative analysis and molecular fingerprinting of methicillin-resistant Staphyloccus aureus nasal colonization in different patient populations: a prospective, multicenter study. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2010;31(6):592–7. doi: 10.1086/652778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furuno JP, Hebden JN, Standiford HC, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Acinetobacter baumannii in a long-term acute care facility. American Journal of Infection Control. 2008;36:768–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds C, Quan V, Kim D, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) carriage in 10 nursing homes in Orange County, California. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2011;32(1):91–3. doi: 10.1086/657637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garazi M, Edwards B, Caccavale D, et al. Nursing homes as reservoirs of MRSA: myth or reality? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2009;10:414–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harbarth S, Fankhauser C, Schrenzel J, et al. Universal screening for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at hospital admission and nosocomial infection in surgical patients. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1149–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hidron AI, Kourbatova EV, Halvosa JS, et al. Risk factors for colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in patients admitted to an urban hospital: emergence of community-associated MRSA nasal carriage. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Jul 15;41(2):159–66. doi: 10.1086/430910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robicsek A, Beaumont JL, Paule SM, et al. Universal surveillance for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 3 affiliated hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Mar 18;148(6):409–18. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee BY, McGlone SM, Wong KF, et al. Modeling the spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) outbreaks throughout the hospitals in Orange County, California. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2011;32(6):562–72. doi: 10.1086/660014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donker T, Wallinga J, Grundmann H. Patient referral patterns and the spread of hospital-acquired infections through national health care networks. PLoS Computational Biology. 2010;6(3):e1000715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robotham JV, Scarff CA, Jenkins DR, et al. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in hospitals and the community: model predictions based on the UK situation. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2007;65(S2):93–9. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(07)60023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith DL, Levin SA, Laxminarayan R. Strategic interactions in multi-institutional epidemics of antibiotic resistance. PNAS. 2005;102(8):3153–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409523102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chamchod F, Ruan S. Modeling the spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in nursing homes for elderly. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes SL, Harris AD, Golden BL, et al. Contribution of interfacility patient movement to overall methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus prevalence levels. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2011;32(11):1073–8. doi: 10.1086/662375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lesosky M, McGeer A, Simor A, et al. Effect of patterns of transferring patients among healthcare institutions on rates of nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission: a monte carlo simulation. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2011;32(2):136–47. doi: 10.1086/657945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.California Health and Human Services Agency. Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development; Sacramento, CA: 2010. [updated October 4, 2010; cited 2010]; Available from: http://www.oshpd.ca.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang SS, Avery TR, Song Y, et al. Quantifying interhospital patient sharing as a mechanism for infectious disease spread. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2010;31(11):1160–9. doi: 10.1086/656747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elkins KR, Nguyen CC, Kim D, et al. Successful strategies for high participation in three regional healthcare surveys: an observational study. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2011;11:176. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Minimum Data Set. Baltimore, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. [updated April 12, 2011; cited 2010] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy CR, Quan V, Kim D, et al. Nursing home characteristics associated with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) burden and transmission. BMC Infectious Disease. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-269. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang S, Sethi AK, Eckstein BC, et al. Skin and environmental contamination with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among carriers identified clinically versus through active surveillance. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 May 15;48(10):1423–8. doi: 10.1086/598505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang SS, Rifas-Shiman SL, Warren DK, et al. Improving methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus surveillance and reporting in intensive care units. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;195:330–8. doi: 10.1086/510622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robicsek A, Beaumont JL, Peterson LR. Duration of colonization by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus after hospital discharge and risk. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48:910–3. doi: 10.1086/597296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanford MD, Widmer AF, Bale MJ, et al. Efficient detection and long-term persistance of the carriage for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1994;19(6):1123–8. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.6.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scanvic A, Denic L, Gaillon S, et al. Duration of colonization by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus after hospital discharge and risk factors for prolonged carriage. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;32(10):1393–8. doi: 10.1086/320151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kluytman J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1997;10(3):505–20. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kellie SM, Timmins A, Brown C. A statewide collaborative to reduce methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremias in New Mexico. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011 Apr;37(4):154–62. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flanagan ME, Welsh CA, Kiess C, et al. A national collaborative for reducing health careassociated infections: current initiatives, challenges, and opportunities. Am J Infect Control. 2011 Oct;39(8):685–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ward MM, Clabaugh G, Evans TC, et al. A successful, voluntary, multicomponent statewide effort to reduce health care-associated infections. Am J Med Qual. 2012 Jan-Feb;27(1):66–73. doi: 10.1177/1062860611405506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Datta R, Quan V, Kim D, et al., editors. Negative correlation between MRSA and MSSA prevalence in nursing homes; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Annual Meeting; 2011 April 1–4; Dallas, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mody L, Kauffman CA, Donabedian S, et al. Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in nursing home residents. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 May 1;46(9):1368–73. doi: 10.1086/586751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trick WE, Weinstein RA, DeMarais PL, et al. Colonization of skilled-care facility residents with antimicrobial-resistant pathogens. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Mar;49(3):270–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4930270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bradley SF, Terpenning MS, Ramsey MA, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: colonization and infection in a long-term care facility. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Sep 15;115(6):417–22. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-6-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muder RR, Brennen C, Wagener MM, et al. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcal colonization and infection in a long-term care facility. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Jan 15;114(2):107–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-2-1-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang SS, Hinrichsen VL, Datta R, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection and hospitalization in high-risk patients in the year following detection. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mulhausen PL, Harrell LJ, Weinberger M, et al. Contrasting methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in Veterans Affairs and community nursing homes. Am J Med. 1996 Jan;100(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Capitano B, Leshem OA, Nightingale CH, et al. Cost effect of managing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a long-term care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 Jan;51(1):10–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5215.2002.51003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suetens C, Niclaes L, Jans B, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization is associated with higher mortality in nursing home residents with impaired cognitive status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006 Dec;54(12):1854–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(15):1763–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Avery TR, Kleinman KP, Klompas M, et al. Inclusion of 30-day postdischarge detection triples the incidence of hospital-onset methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012 Feb;33(2):114–21. doi: 10.1086/663714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradley SF. Issues in the management of resistant bacteria in long-term-care facilites. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 1999;20(5):362–7. doi: 10.1086/501637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee BY. Digital decision making: computer models and antibiotic prescribing in the twenty-first century. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46(8):1139–41. doi: 10.1086/529441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]