Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to test the hypothesis that the loudness dependence of auditory evoked potentials (LDAEP) can be used to predict the presence of bipolarity in patients with major depressive episodes.

Methods

A cohort of 61 patients who met the criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) following diagnosis using Axis I of the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-text revision, and who had no history of hypomanic or manic episodes was included in this study. The patients were stratified into two subgroups based on whether or not they achieved a positive score for the Korean versions of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (K-MDQ). The LDAEP was evaluated by measuring the auditory event-related potentials before beginning medication with serotonergic agents.

Results

The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) score was also higher for the positive screening group (81.24±11.87) than for the negative screening group (73.30±14.92; p=0.039, independent t-test). However, the LDAEP, Beck Depression Inventory, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), and Hamilton Anxiety Scale scores did not differ significantly between them. When binary logistic regression analysis was carried, the relationship between the positive or negative subgroups for K-MDQ and BIS or Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) score was also significant (respectively, p=0.017, p=0.038).

Conclusion

We found that LDAEP was not significantly different between depressive patients with and without bipolarity. However, our study has revealed the difference between two subgroups based on whether or not they achieved a positive score for the K-MDQ in BIS or BSS score.

Keywords: LDAEP, Major depressive disorder, Bipolarity, Bipolar spectrum disorder

INTRODUCTION

The loudness dependence of auditory evoked potentials (LDAEP) is considered to be a valid indicator of the brain's serotonin activity, and has been identified as being inversely associated with central serotonergic activity, with a weak LDAEP reflecting high serotonergic neurotransmission.1-6

Several studies have investigated the LDAEP in psychiatric disorders. LDAEP was found to be significantly weaker in schizophrenia patients than in healthy subjects, indicating higher serotonergic activity in these patients.7 These results are consistent with the serotonin hypothesis of schizophrenia. In the case of major depressive disorder (MDD), no significant difference in the LDAEP was found between depressive patients and healthy subjects.8 Few studies have considered bipolar disorder. It was reported that as in schizophrenia, the LDAEP is significantly weaker in bipolar patients than in healthy subjects and patients with major depressive disorder.9 However, that study did not separate bipolar patients according to the current mood state, such as mania, depression, and euthymia. Lee et al.10 recently reported on the LDAEP of multiple mood statuses (i.e., bipolar depression, mania, and euthymia) and its clinical implications in bipolar disorder patients. They found that serotonin function, as reflected by the LDAEP, varied with current mood status, and weakened in the following order: healthy subjects, euthymia, bipolar depression, and bipolar mania. Fitzgerald et al.11 found that the melancholic depressive patients had a significantly weaker LDAEP than the non-melancholic depressive patients and there was no difference in LDAEP between the non-melancholic depressive group and control group. They explained that melancholic depression is likely to involve multiple neurotransmitter systems and the action of noradrenergic abnormalities may be to produce an increase in serotonin tone. In addition, Parker et al.12 reported that bipolar depression corresponds closely to melancholic depression in terms of its clinical phenotype. Thus, we hypothesized that stronger LDAEP would be observed in patients with bipolar depression compared to patients with MDD.

No studies to date have considered the LDAEP in individuals with MDD who display subsyndromal hypomanic features, not concurrent with a major depressive episode (i.e., subthreshold bipolarity). We also hypothesized that LDAEP can differentiate between patients with MDD and those with MDD who report subsyndromal hypomania, outside the context of a major depressive episode without a clear hypomanic or manic episode. This is a very important issue, because patients who have bipolar disorder can be misdiagnosed and inappropriately treated, contributing significantly to treatment failure. For example, bipolar patients placed on antidepressant monotherapy may fail to respond, or their symptoms may even worsen.

The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that LDAEP can be used to predict the presence of bipolarity in patients with a major depressive episode. The question of whether there are clinical differences between depressive patients with and without bipolarity was also addressed.

METHODS

Subjects

The subjects with a major depressive episode agreed to participate in our study. They met the criteria for MDD following diagnosis using Axis I of the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)-text revision. They had no history of hypomanic or manic episodes. The LDAEP was evaluated by measuring the auditory event-related potential before beginning medication with serotonergic agents. In addition, the Korean versions of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (K-MDQ) were used as screening tools to help identify bipolarity. The validity of the K-MDQ, a screening instrument for bipolar disorder, has been tested by Korean researchers, it was found to have a high Cronbach's alpha (0.88).13 A total K-MDQ score of at least 7 (excluding further two questions) was chosen as the optimal cutoff, as it showed good sensitivity (0.75) and specificity (0.69).

The cohort was stratified into two subgroups depending on whether or not they achieved a positive score for the K-MDQ. Subjects who had psychotic symptoms, any additional mental disorders on Axis I or II of the DSM-IV, or major medical and neurological disorders were excluded in order to remove contamination. The included cohort comprised 61 subjects. Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all of the subjects before beginning the investigation.

Depression severity was assessed using the clinician-administered 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17),14 and the self-reported Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).15 Furthermore, the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS),16 the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS),17 the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA),18 and the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS)19 were applied. The findings from some subjects in this study have been reported previously.20

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital. Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all patients before beginning the investigation.

EEG methods

The potential confounding influences of drugs were minimized by measuring the LDAEP before treatment with antidepressants or serotonergic agents. None of the patients had taken any psychotropic agent other than a hypnotic drug (benzodiazepine or zolpidem) for a minimum 3 months before visiting our hospital.

Each subject was seated in a comfortable chair in a sound-attenuated room. The auditory stimulation comprised 1000 stimuli with an interstimulus interval randomized to between 500 and 900 ms. Tones of 1000 Hz and 80-ms duration (with a 10-ms rise and fall times) were presented at five intensities (55, 65, 75, 85, and 95 dB SPL) via headphones (MDR-D777, Sony, Tokyo, Japan). E-Prime software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) generated the stimuli. EEG data were recorded from 32 scalp sites using silver/silver-chloride electrodes according to the international 10-20 system (impedance <10 kΩ), using an Auditory Neuroscan NuAmp amplifier (Compumedics USA, El Paso, TX, USA). Data were collected at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz, using a bandpass filter from 0.5 to 100 Hz. In addition, four electrodes were used to measure both horizontal and vertical electrooculograms.

Data were reanalyzed using Scan 4.3 software with a bandpass filter from 1 to 30 Hz, and ocular contamination was removed using standard blink-correction algorithms.21 Event-related potential sweeps with artifacts exceeding 70 µV were rejected at all electrode sites. For each intensity and for each subject, the N1 peak (negative-most amplitude between 80 and 130 ms after the stimulus) and P2 peak (positive-most peak between 130 and 230 ms after the stimulus) were then determined at the Cz electrode.

The peak-to-peak N1/P2 amplitudes were calculated for the five stimulus intensities, and the LDAEP was calculated as the slope of the linear-regression curve.

Analysis

The demographic, psychopathological, and biological measures of the two groups were compared using Student's t-test, the chi-square test, and correlation analysis (Pearson's correlation). In addition, binary logistic regression analysis was carried to to adjust odds ratios for the bipolarity by LDAEP when HDRS, BDI, HAMA, BIS, BHS, and BSS were considered. All tests were two tailed, and group differences were tested at the p<0.05 level.

RESULTS

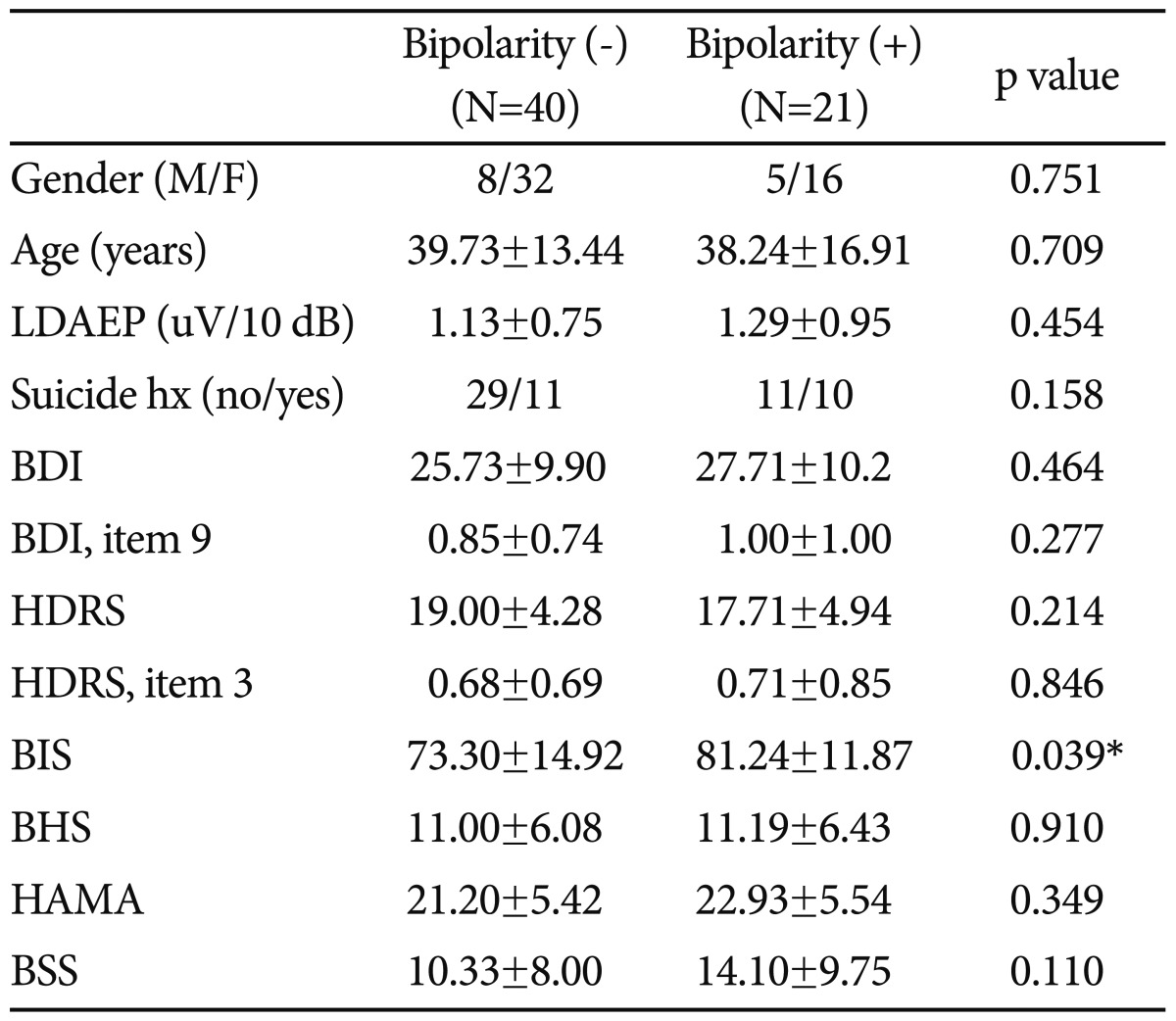

In our sample of 61 subjects with MDD, the mean age and the HDRS-17 and BDI scores were 39.21±14.60 years, 18.16±4.84, and 26.41±9.98, respectively. The subjects were divided into two groups according to whether they screened positive or negative for bipolarity with the K-MDQ, and the two groups were compared regarding several variables (Table 1).

Table 1.

Gender, age, LDAEP, and psychometric ratings of depressive patients with bipolarity and without bipolarity

*p<0.05. F: female, M: male, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, BIS: Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, BHS: Beck Hopelessness Scale, HAMA: Hamiton Anxiety Scale, BSS: Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, LDAEP: Loudness Dependence of Auditory Evoked Potentials, hx: history

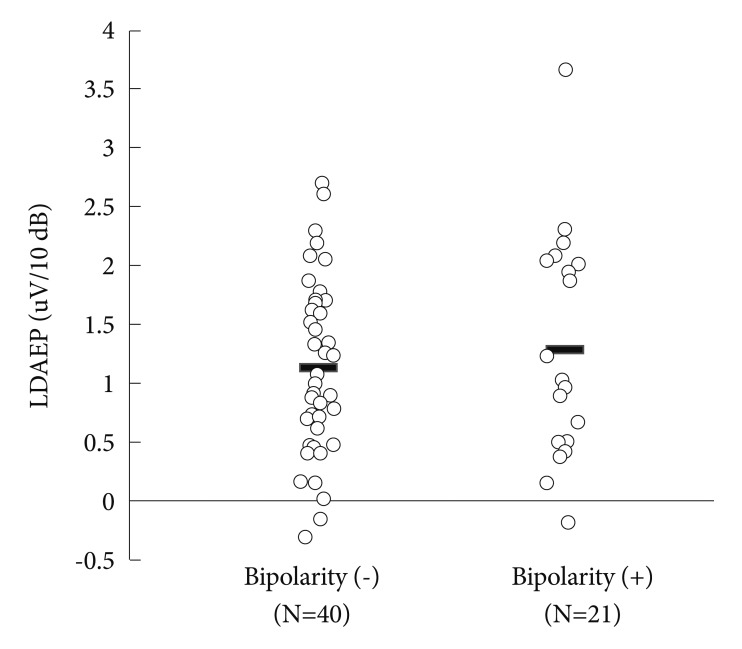

There were no between-group differences in the gender distribution and age (respectiviely, p=0.751, p=0.709). The BIS score was also higher for the positive screening group (81.24±11.87) than for the negative screening group (73.30±14.92; p=0.039, independent t-test). However, the LDAEP (Figure 1), BDI, HAMD, BHS, and HAMA scores did not differ significantly between them, and there was no correlation between the K-MDQ score and LDAEP strength (Pearson's test). The number of subjects who had attempted suicide did not differ significantly between them (χ2=2.469, p=0.158). However, correlation analysis (Pearson's test) revealed the significant correlation between total MDQ score and BIS or BSS score (respectively, p=0.001, p=0.049).

Figure 1.

Comparison of LDAEP between depressive patients with bipolarity and depressive patients without bipolarity. Mean values were presented as horizontal bars. There was no significant difference between two groups. LDAEP: Loudness Dependence of Aoditory Evoked Potentials.

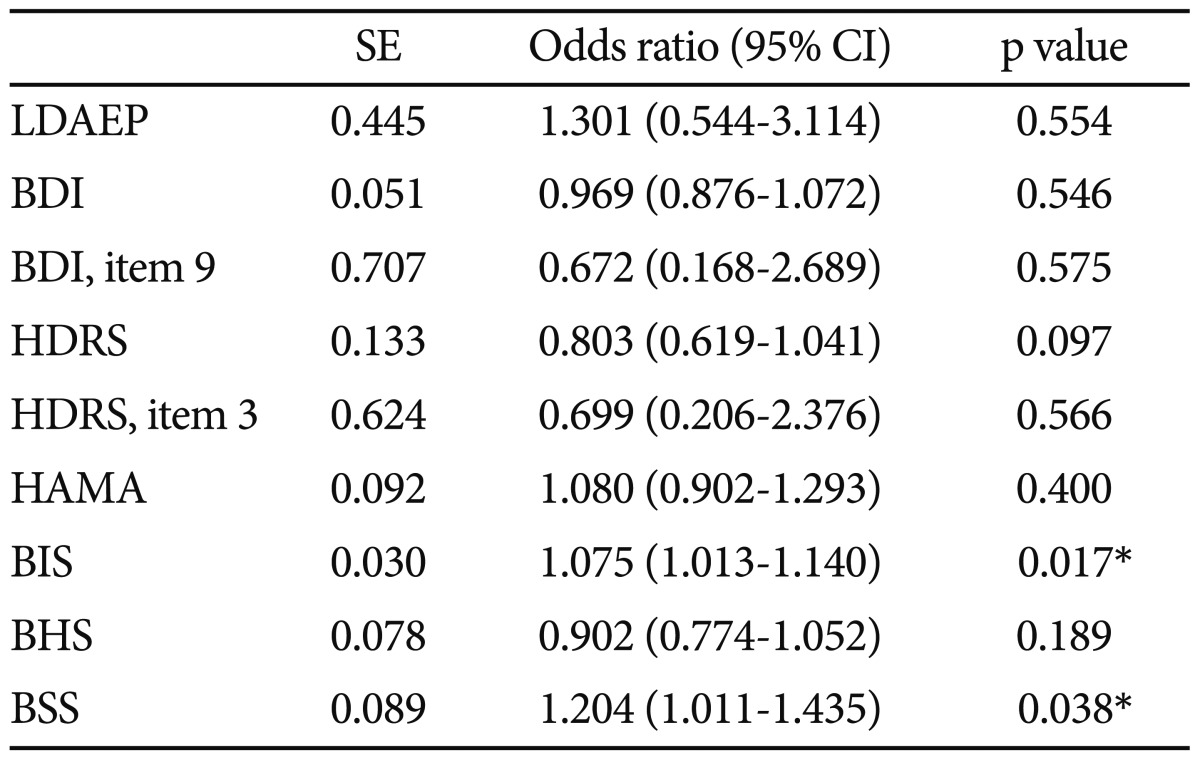

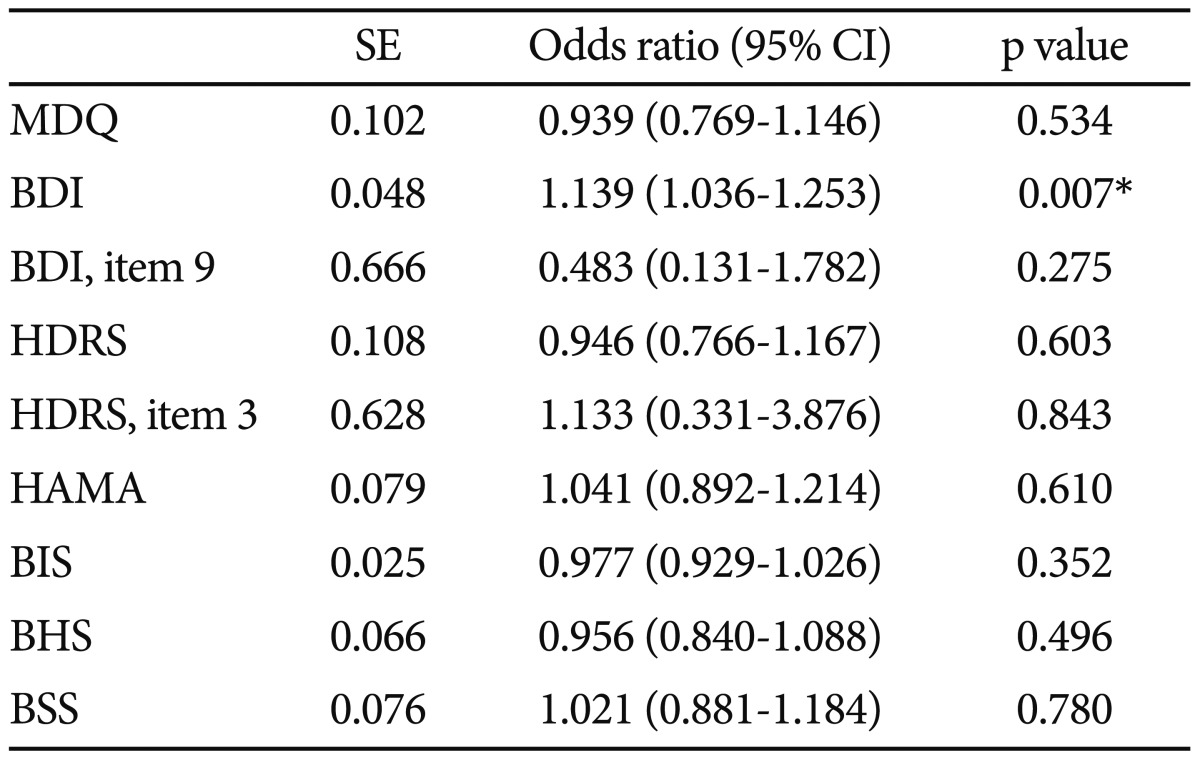

When binary logistic regression analysis for bipolarity was carried, the relationship between total MDQ score and BIS or BSS score was also significant (respectively, p=0.017, p=0.038)(Table 2). In addition, when binary logistic regression analysis for LDAEP was carried, the relationship between LDAEP value and total BDI score was also significant (p=0.007)(Table 3).

Table 2.

Binary logistic regression analysis for bipolarity

*p<0.05. SE: standard error, CI: confidence interval, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, BIS: Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, BHS: Beck Hopelessness Scale, HAMA: Hamilton Anxiety Scale, BSS: Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, LDAEP: Loudness Dependence of Auditory Evoked Potentials

Table 3.

Binary logistic regression analysis for LDAEP

*p<0.05. SE: standard error, CI: confidence interval, MDQ: Mood Disorder Questionnaire, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, BIS: Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, BHS: Beck Hopelessness Scale, HAMA: Hamilton Anxiety Scale, BSS: Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, LDAEP: Loudness Dependence of Auditory Evoked Potentials

DISCUSSION

Our results did not reveal differences in LDAEP between depressive patients with and without bipolarity. However, to date there have been no study on the LDAEP of patients with bipolarity. There have been some studies related to some personality style and bipolar disorder.

It was reported that the existence of significant negative correlations between the strength of the LDAEP and both hyperthymic temperament and hypomanic personality.22 Our previous research addressed the LDAEP in psychiatric disorders and showed that the LDAEP was weaker in bipolar patients than in healthy subjects.9 However, one limitation of this study is that our bipolar sample included both manic and depressive patients.

In contrast, it was found that a strong LDAEP may be characteristic of healthy subjects with an action-oriented and extroverted personality style, such as sensation seeking, impulsivity, and extraversion. Norra et al.23 described a correlation between a strong LDAEP and aspects of impulsiveness in borderline patients. Some findings suggest that sensation seeking and impulsivity are also related to the premorbid personality of bipolar disorder.24,25 Our recent research also revealed that the LDAEP varies according to mood status.10 Analysis of the LDAEP revealed a tendency toward decreasing strength in patients in the following order: healthy controls, patients with bipolar euthymia, patients with bipolar depression, patients with bipolar mania, and patients with schizophrenia. A post hoc analysis revealed that the LDAEP was significantly stronger in patients with bipolar depression than in those with schizophrenia, stronger in bipolar euthymia than in schizophrenia, and stronger in healthy controls than in patients with bipolar mania. Therefore, the strength of the LDAEP in bipolar disorder remains controversial.

We found that LDAEP was not significantly different between patients with positive scores for K-MDQ and those with negative K-MDQ scores. This means that that the central serotonergic activity is not different between patients with coexisting major depressive episodes and bipolarity and those with major depressive episodes but without bipolarity. Measurement of the LDAEP appears not to be clinically useful, enabling the prediction of bipolarity in MDD patients. Our study also reveals that the score for BIS was significantly higher in the bipolarity group than in the non-bipolarity group. This results are consistent with previous studies.24,26 When binary logistic regression analysis for bipolarity was carried, the relationship between the positive or negative subgroups for K-MDQ and BIS or BSS score, which reflects suidal ideation, was also significant. This suggests that clinicians should monitor depressive patients with bipolarity particularly carefully for suicidality. In addition, when binary logistic regression analysis for LDAEP was carried, the relationship between LDAEP value and total BDI score. This suggests that there is the negative correlation between serotonergic activity and depression severity.

The small sample in this study limits the generalizability of our findings. In addition, MDQ is used as only a screening tool to help identify bipolarity, not bipolarity itself. However, despite these limitations, our study has revealed the difference between two subgroups based on whether or not they achieved a positive score for the K-MDQ in BIS or BSS score. More studies with larger cohorts and measuring the differences between bipolarity and non-bipolarity group are needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by Ministry of Education and Science Technology (MEST) (2011-0010562). The authors would like to thank Joo EH for their assistance with data collection.

References

- 1.Buchsbaum M, Silverman J. Stimulus intensity control and the cortical evoked response. Psychosom Med. 1968;30:12–22. doi: 10.1097/00006842-196801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hegerl U, Gallinat J, Juckel G. Event-related potentials. Do they reflect central serotonergic neurotransmission and do they predict clinical response to serotonin agonists? J Affect Disord. 2001;62:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hegerl U, Juckel G. Intensity dependence of auditory evoked potentials as an indicator of central serotonergic neurotransmission: a new hypothesis. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;33:173–187. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juckel G, Hegerl U, Molnar M, Csepe V, Karmos G. Auditory evoked potentials reflect serotonergic neuronal activity--a study in behaving cats administered drugs acting on 5-HT1A autoreceptors in the dorsal raphe nucleus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:710–716. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park YM, Kim DW, Kim S, Im CH, Lee SH. The loudness dependence of the auditoryevoked potential (LDAEP) as a predictor of the response to escitalopram in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;213:625–632. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2061-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park YM, Lee SH, Park EJ. Usefulness of LDAEP to predict tolerability to SSRIs in major depressive disorder: a case report. Psychiatry Investig. 2012;9:80–82. doi: 10.4306/pi.2012.9.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gudlowski Y, Ozgürdal S, Witthaus H, Gallinat J, Hauser M, Winter C, et al. Serotonergic dysfunction in the prodromal, first-episode and chronic course of schizophrenia as assessed by the loudness dependence of auditory evoked activity. Schizophr Res. 2009;109:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linka T, Sartory G, Bender S, Gastpar M, Müller BW. The intensity dependence of auditory ERP components in unmedicated patients with major depression and healthy controls. An analysis of group differences. J Affect Disord. 2007;103:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park YM, Lee SH, Kim S, Bae SM. The loudness dependence of the auditory evoked potential (LDAEP) in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, and healthy controls. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:313–316. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KS, Park YM, Lee SH. Serotonergic dysfunction in patients with bipolar disorder assessed by the loudness dependence of the auditory evoked potential. Psychiatry Investig. 2012;9:298–306. doi: 10.4306/pi.2012.9.3.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzgerald PB, Mellow TB, Hoy KE, Segrave R, Cooper NR, Upton DJ, et al. A study of intensity dependence of the auditory evoked potential (IDAEP) in medicated melancholic and non-melancholic depression. J Affect Disord. 2009;117:212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker G, McCraw S, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Hong M, Barrett M. Bipolar depression: Prototypically melancholic in its clinical features. J Affect Disord. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.035. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jon DI, Hong N, Yoon BH, Jung HY, Ha K, Shin YC, et al. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50:286–291. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42:861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maier W, Buller R, Philipp M, Heuser I. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change in anxiety and depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 1988;14:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47:343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DH, Park YM. The association between suicidality and serotonergic dysfunction in depressed patients. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semlitsch HV, Anderer P, Schuster P, Presslich O. A solution for reliable and valid reduction of ocular artifacts, applied to the P300 ERP. Psychophysiology. 1986;23:695–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hensch T, Herold U, Brocke B. An electrophysiological endophenotype of hypomanic and hyperthymic personality. J Affect Disord. 2007;101:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norra C, Mrazek M, Tuchtenhagen F, Gobbelé R, Buchner H, Sass H, et al. Enhanced intensity dependence as a marker of low serotonergic neurotransmission in borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karakus G, Tamam L. Impulse control disorder comorbidity among patients with bipolar I disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bizzarri JV, Sbrana A, Rucci P, Ravani L, Massei GJ, Gonnelli C, et al. The spectrum of substance abuse in bipolar disorder: reasons for use, sensation seeking and substance sensitivity. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:213–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katzow JJ, Hsu DJ, Ghaemi SN. The bipolar spectrum: a clinical perspective. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:436–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-5618.2003.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]