Abstract

Objectives. To implement and evaluate a 3-year reflective writing program incorporated into introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs) in the first- through third-year of a doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) program.

Design. Reflective writing was integrated into 6 IPPE courses to develop students’ lifelong learning skills. In their writing, students were required to self-assess their performance in patient care activities, identify and describe how they would incorporate learning opportunities, and then evaluate their progress. Practitioners, faculty members, and fourth-year PharmD students served as writing preceptors.

Assessment. The success of the writing program was assessed by reviewing class performance and surveying writing preceptor’s opinions regarding the student’s achievement of program objectives. Class pass rates averaged greater than 99% over the 8 years of the program and the large majority of the writing preceptors reported that student learning objectives were met. A support pool of 99 writing preceptors was created.

Conclusions. A 3-year reflective writing program improved pharmacy students’ reflection and reflective writing skills.

Keywords: pharmacy student, introductory pharmacy practice experience, lifelong learning

INTRODUCTION

Metacognition or “thinking about thinking” is valued in educational and workplace settings as a way for individuals to improve future performance through reflection and self-assessment of past performance.1 Within healthcare professions, reflection and reflective writing about practice experiences are valued, as these skills can be used to develop lifelong learning strategies. Also, healthcare licensing and accrediting bodies have implemented standards for reflection and reflective writing.1 With respect to pharmacy, reflection improves students’ critical-thinking skills, while reflective writing allows pharmacy students to document achievement of multiple ability-based outcomes.2,3 The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education encourages students to assume responsibility for their own learning including self-assessment of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values, together with development of personal learning plans and maintenance of student portfolios.4

If pharmacy graduates are expected to use reflection and reflective writing as lifelong learning strategies then it is reasonable that pharmacy students should learn and practice these skills throughout pharmacy school as a way to ingrain them as behaviors. However, reflection is not an intuitive skill1,5 so students need to receive appropriate mentoring and feedback to develop it.1,6-10 The need for large classes of students to receive detailed and individualized feedback on their reflective writing necessitates the use of large numbers of writing preceptors.

To address these challenges, in 2004, the Skaggs School of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences developed a required 3-year reflective writing program and integrated it into a sequence of 6 introductory pharmacy practice experience (IPPE) courses. A group of writing preceptors to sustain the writing program each year for 3 classes of 160 students were recruited. In this paper, we describe the program and report on the writing preceptors and student opinions regarding the program’s value and the preceptors’ reasons for participating.

DESIGN

The primary goal of the reflective writing program was to develop students’ lifelong learning skills. The primary strategy used to achieve that goal was to develop students’ ability to self-assess their competency to care for patients in experiential practice sites. Students were required to use self-assessment skills to identify learning opportunities and to act on and evaluate the outcome of those learning opportunities. Restated with reference to Bloom’s taxonomy, students were tasked with integrating and applying didactic knowledge and skills in the practice setting, forming strategies to improve this performance based on their reflection, and evaluate how these strategies impacted their patient care performance.11

When the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences implemented its PharmD degree program in 1999, 6 IPPE courses were included in the curriculum (1 per semester for the first 3 years) to provide students with 3 contact hours per week in which to apply newly acquired knowledge and skills in community, hospital, and other practice settings. The 6 IPPE course syllabi included reflective writing assignments, but the IPPE writing program was limited in its initial years because of logistical issues. Students in the IPPE program were paired with practitioners in a variety of practice settings for periods of up to 2 years. This extended pairing allowed preceptors to form mentor/mentee relationships with the students and customize their teaching approach according to each student’s needs. This long-term association allowed preceptors to identify students’ strengths and weaknesses over time and produced insightful feedback to course directors with respect to individual student performance. Because of workplace pressures, however, this feedback was focused more on select aspects of patient care than on a comprehensive analysis of students’ use of pharmacy practice competencies.

Onsite preceptor feedback is neither specifically targeted at improving students’ reflective skills nor at developing students’ lifelong learning skills. In contrast, reflective writing programs allow students time to analyze their IPPE experiences unrestricted by onsite workplace pressures and can be targeted at lifelong learning skills. Thus, the IPPE reflective writing program was designed to complement the role of onsite preceptors, challenging students to identify the strengths and weaknesses of their performance on site and, based on that self-analysis, identify learning opportunities and develop strategies to improve their performance. Similar to the one-to-one pairing of students with onsite practitioners, the reflective writing program was designed to establish long-term mentor/mentee relationships between students and pharmacists. Such relationships allowed writing preceptors to provide formative feedback on students’ work such that students could revise and resubmit their work as many times as necessary during a semester to meet their writing preceptor’s expectations. Long-term mentor/mentee relationship allowed writing preceptors to track the development of students’ reflective and lifelong learning skills over time.

Members of the fourth-year pharmacy (P4) class were asked to serve as writing preceptors for the P1 class. Approximately 25% to 30% of the class volunteered each year and each volunteer was given year-long responsibility for 3 or 4 first-year students. The responsibility complemented the P4 students’ APPE program by providing a “shoe on the other foot” opportunity to draw upon their own IPPE writing experiences to mentor P1 students. Overseeing multiple students allowed the P4 students to calibrate the performance of their P1students against each other and, if the performance of any P1 student gave cause for alarm, the P4 student was required to consult with the course director.

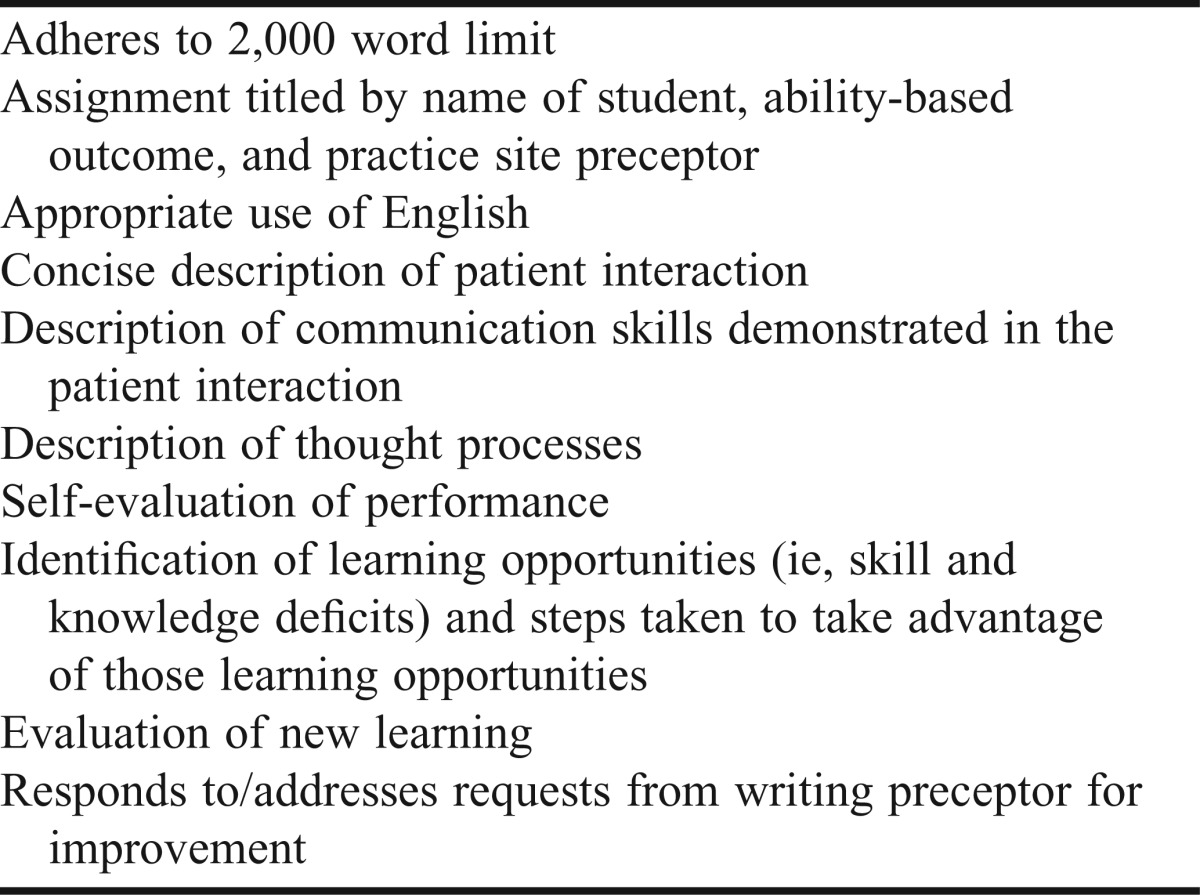

Writing preceptors for P2 and P3 students were faculty members and volunteers from the practice community. Each writing preceptor was given a 2-year responsibility for 3 or 4 students (ie, the pairings were established at the start of the P2 year and maintained through the end of the P3 year).The writing preceptors’ primary responsibility was to mentor students in developing their reflective skills and, for those students initially skeptical of reflection and reflective writing, to develop their awareness of the importance of these skills in lifelong learning. They evaluated students’ writing on a 4-point system (exceeds expectations, meets expectations, meets expectations with limitations, and below expectations) aided by a rubric that addressed each domain listed in Table 1 (copy available upon request from the corresponding author) taking into account each student’s place in the IPPE program. Work was either approved or rejected for further revisions, with formative feedback provided to students in either case.Writing preceptors were asked to spend an average of 30 minutes reading and providing feedback on each P2 or P3 writing assignment (ie, commit an average of 2 hours per student per semester), and were encouraged to review their students’ earlier work and the feedback provided. Preceptors were told to highlight strengths within the students’ writing to build students’ self-confidence and to identify areas for improvement regardless of how well a student performed. Writing preceptors identified learning opportunities beyond those identified by the students themselves and, having demonstrated that learning opportunities were overlooked, challenged students to identify additional learning opportunities and submit a revised assignment for grading. They were also asked to provide feedback regarding instances where an ability-based outcome was used without recognition by the student. Students often demonstrated communication skills and professionalism in their performance but did not recognize and report on these elements, so to optimize the reflective process, students needed to become more aware of their use of these ability-based outcomes.

Table 1.

Writing Assignment Checklist

While the writing preceptors provided specific feedback to the students, the IPPE course directors were responsible for ensuring students understood the philosophy and principles of reflection and reflective writing in the development and maintenance of lifelong learning skills. The course directors placed reflection and reflective writing in the context of career development by emphasizing that IPPE writing assignments constituted a portfolio of each student’s work which would be valuable in pursuing residency, fellowship, and career opportunities. They put reflection and reflective writing in the context of traditional classroom examinations in that students were challenged to perform to the best of their capabilities.

The IPPE course directors also were responsible for supporting the students and writing preceptors throughout the program. They addressed student concerns regarding preceptor timeliness and expectations, and were responsible for training and orienting preceptors on how to properly provide feedback to guide students through this process. This training was held twice a year, with the core feature requiring writing preceptors to read and evaluate writing samples first individually and then as a group in an effort to standardize the feedback and expectations of writing. Finally, course directors would assume responsibility for those students who were identified as requiring increased time and attention for their work beyond what a volunteer writing preceptor could provide.

To augment preceptor training in minimizing inter-rater variability in grading and feedback, a major/minor writing preceptor concept was introduced. Beginning in 2010, students in the P2 spring and P3 fall semesters were assigned a second writing preceptor designated as a minor writing preceptor with responsibility for mentoring students for their communication ability-based outcome writing assignments (ie, the workload of students’ major writing preceptors was reduced from 4 to 3 writing assignments per semester for 2 semesters). The minor writing preceptors were recruited from the school’s full-time faculty which permitted each student to be mentored by a full-time faculty member and a volunteer writing preceptor at the same time for 2 semesters. Faculty members were recruited because their mentoring role in the writing program was aided by their knowledge of students’ academic strengths and weaknesses from other parts of the curriculum. Recent graduates were recruited because they had in-depth knowledge of the school’s PharmD curriculum and the IPPE writing program.

Students were required to submit multiple writing assignments each semester during the 3-year IPPE program utilizing the E*Value course management software program (Advanced Informatics, Minneapolis, Minnesota). Writing preceptors used the E*Value system to access and return each student’s work with feedback and to indicate when the work met expectations for passing. Students and writing preceptors could submit and receive assignments and feedback at any time from any location with Internet access (many of the school’s writing preceptors lived and worked outside of Colorado) and would receive e-mail notifications from E*Value when new changes were submitted.

Because first-year students had limited professional knowledge and skills, the P1 writing program was designed to introduce students to reflection and self-assessment of practice-based performance. They undertook patient care responsibilities appropriate for first-year students and submitted writing assignments at regular intervals throughout the year. The students described their experiences and, with respect to reflection and self-assessment, were required to describe their thoughts and opinions regarding those experiences and to identify how and when they used the pre-advanced pharmacy practice competencies in completing their P1 IPPE activities.4

The P2/P3 writing program constituted the core of the IPPE writing program and was focused on students’ ability to describe and analyze their counseling and care of patients in a variety of practice settings. Students submitted 4 writing assignments per semester that addressed 2 specific ability-based outcomes (communication and professionalism) and 2 global ability-based outcomes (care of patients with medications; care of patients with health promotion and disease prevention) . Each assignment had a 2,000 word limit to encourage quality rather than quantity. Deadlines for the initial and final writing assignments were set at 4 and 8 weeks, respectively, after the start of each semester. The students chose which 2 of the 4 writing assignments to submit by the first deadline. The writing preceptors were asked to provide feedback within 2 weeks after students submitted their work and were encouraged to incorporate their feedback within the student’s text (ie, maintain the student’s work and the preceptor’s feedback in 1 file) and to use a font color that distinguished their feedback from the student’s writing.

Students were required to describe and analyze their care of a patient that demonstrated her/his command of 1 of the 4 ability-based outcomes. A different patient had to be chosen for each of the 4 outcomes. Each writing assignment had to contain a narrative (∼500 words) and reflective (∼1,500 word) component. A checklist of requirements was provided for students and writing preceptors (Table 1). The narrative served to orient the writing preceptor to the case and to outline the student’s thinking and decision-making skills. For example, if a student decided a patient’s symptoms were the result of a viral infection, they outlined the thought processes that led to that conclusion, including the consideration given to other potential etiologies for the patient’s symptoms. The narrative also required students to describe their use of communication skill regardless of the ability-based outcome addressed in the writing assignment. While one of the ability-based outcome writing assignments was focused on communication, communication skills were considered sufficiently important that students were to address them in all writing assignments.

The reflective component of the writing assignments required students to identify the strengths and weaknesses of their performance and to conceive, apply, and evaluate strategies designed to build on the strengths and address the weaknesses. For example, if a student reflected that he had forgotten to introduce himself as a pharmacy student to a patient, in response, he may have described how he created a simple performance checklist to guide his future patient interactions. Students had to identify skill deficits. For example, in analyzing her ability to measure a patient’s blood pressure, a student may have identified that she lacked skill in wrapping the sphygmomanometer cuff around the patient’s arm and described that, to address this deficiency, she had measured the blood pressure of classmates and family members until she judged herself competent in that skill. Students also were to identify and address knowledge deficits. For example, if a student encountered a patient with limited English skills, he may have later described the encounter and the outcome of his search for resources available at the practice site to help overcome language barriers with future patients.

Students were required to demonstrate increasing competency to counsel and care for patients in a progressive manner throughout the IPPE program and that improvement had to be reflected in their IPPE writing assignments. For example, a student may have described in her first P2 writing assignment how she interviewed a patient regarding a self-care issue to establish the nature and history of the patient’s symptoms and presented that information to the onsite preceptor for him to advise the patient. In comparison, P3 students had to satisfy their onsite and writing preceptors that they were competent to independently counsel and care for patients regarding prescription and nonprescription medications and health promotion and disease prevention. Students were required to choose patients who represented different challenges from those described in previous writing assignments. For example, students who spoke Spanish were expected to showcase their multilingual skills in only one P2 or P3 writing assignment.

Students also had to demonstrate responsiveness to feedback from their writing preceptors. Accordingly, students were encouraged to reread all previous feedback prior to completing a new writing assignment. Students had to respond within 2 weeks if required to revise a writing assignment and choose a font color to distinguish their revised work from their original work and the writing preceptor’s formative comments.

Students had to demonstrate progressive improvement in their reflective lifelong learning skills. While their reflections early in the P2 year might show only small numbers of simple patient care improvements, by the end of the P3 year, students had to be able to use reflection to show multiple and complex improvements. For example, a P2 student wrote how he introduced himself as a pharmacy student to a patient in the nonprescription medication aisles of a community pharmacy and, after-the-fact, decided he would have appeared more self-confident and authoritative if he had introduced himself by name as well as by his pharmacy student status. The student evaluated the strategy by measuring its impact on the proportion of patients who accepted his offer to help with their self-care needs. In contrast, a P3 student wrote about her ability to counsel patients on potentially embarrassing topics. Based on a parent she encountered reading the label of a head lice product, she decided it would be an improvement to begin similar encounters by stating that head lice products are a best-selling product. She used her knowledge of human nature to recognize that people derive comfort from knowing their problems are shared by other people and, for that reason, parents purchasing a head lice product are less likely to be embarrassed if they know head lice in children is a common problem. She then evaluated the strategy by gauging its impact on the comfort level of parents she counseled on the treatment of head lice.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

A pass/fail grading system was used for all IPPE courses. Grading encompassed onsite preceptor summative evaluations, successful completion of all mandatory practice site visits, and writing competency assessments. With respect to the IPPE reflective writing program, students had to receive grades of “exceeds expectations” or “meets expectations” for all writing assignments in order to successfully pass the course. Students had to prove through their writing assignments that their competency to counsel and care for patients expressed through 4 ability-based outcomes (communication; professionalism; patient care with prescription and nonprescription medications; patient care with health promotion and disease prevention) increased from one semester to the next and that they were on track to meet IPPE program outcomes by the end of the P3 year. Students, at the completion of the P3 year, had to have proven their ability to care for a variety of patients (eg, infant, pregnant, and frail elderly patients); patients with simple and complex medication regimens; and patients with single and multiple disease states. In addition, students had to prove their ability to identify, act on, and evaluate a wide variety of simple and complex learning opportunities based on their IPPE practice site experiences.

The average pass rate for students in the IPPE reflective writing program from 2005-2012 exceeded 99%. The pass rate included 73 students who failed to achieve “pass” grades within course timelines but who were subsequently successful in doing so without a delay in their academic program. Five students were assigned “fail” grades.

The P2-P3 writing preceptor pool grew from 20 in 2004-2005 to 99 in 2011-2012 and the average (SD) number of years of participation increased from 1.4 ± 0.5 years in 2005/06 to 2.7 ± 1.7 years in 2011/2012. In the 2011-2012 academic year, 99 individuals served as P2/P3 writing preceptors; 19 were full-time clinical faculty members, 79 were recent PharmD graduates, and 1 was a pharmacist recruited from the practice community. Eighty-one of 180 writing preceptors (45%) who participated in the program at any time between 2004-2005 and 2011-2012 withdrew from the program. As of 2012, 9 full-time faculty members served as minor writing preceptors with responsibility for between 12 and 25 students in contrast to the volunteer major writing preceptors who had responsibility for 3 or 4 students.

The 2011-2012 writing preceptors who were recent graduates were surveyed regarding the writing program as an IPPE continuous quality improvement initiative (designated exempt from Institutional Review Board approval). The survey response rate was 83% (64/77). The current practice settings reported by the respondents were academia (14%), community pharmacy/retail (32%), hospital–staff (2%), hospital-clinical (25%), managed care (8%), pharmaceutical industry (2%), and other (18%). Approximately two-thirds of the respondents reported that 3 was the optimum number of students per writing preceptor and that they spent an average of 30 minutes grading and providing feedback to each student on each writing assignment.

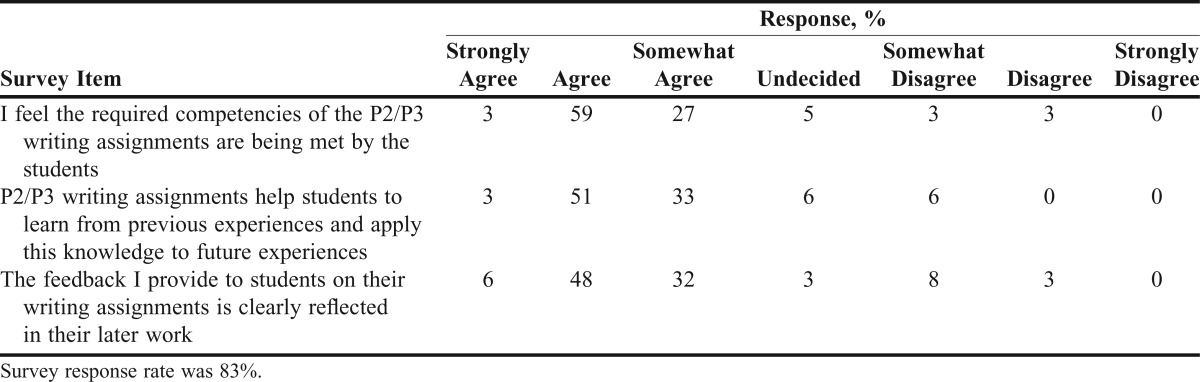

Eighty-nine percent of the respondents strongly agreed, agreed, or somewhat agreed that P2 and P3 students were meeting the required ability-based outcomes (Table 2). Eighty-seven percent strongly agreed, agreed, or somewhat agreed that the P2 and P3 writing assignments helped students to learn from their practice experiences and apply that learning to future experiences. Eighty-six percent of the respondents strongly agreed, agreed, or somewhat agreed that their feedback to students was clearly reflected in the students’ later work.

Table 2.

Writing Preceptors’ Opinions Regarding Pharmacy Student Learning, N = 64

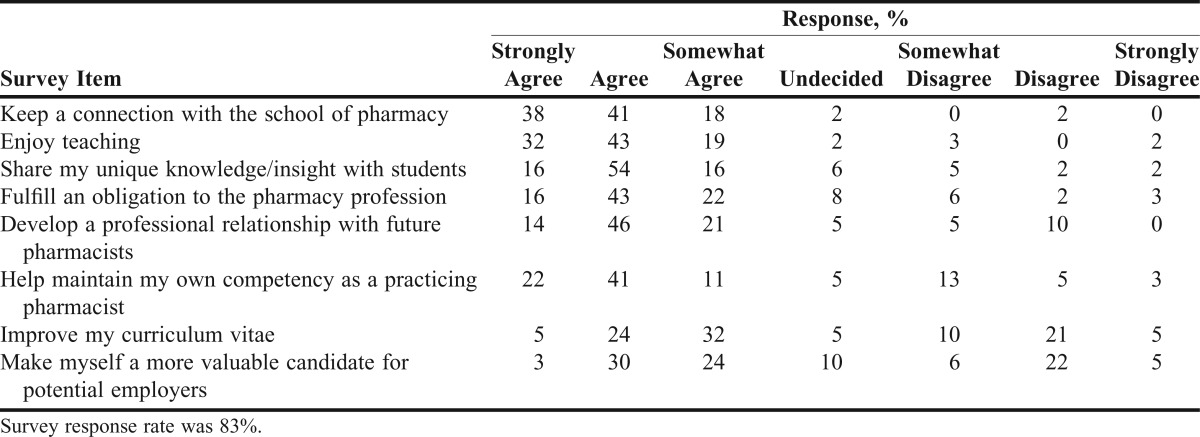

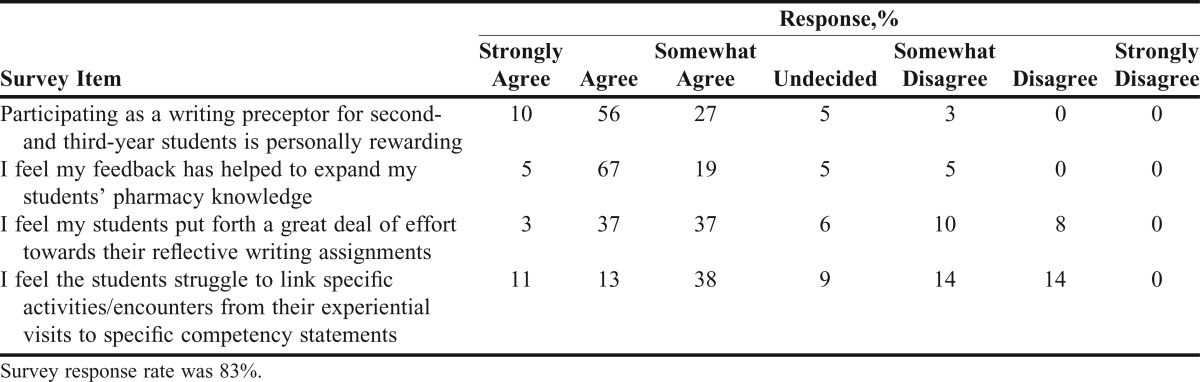

Table 3 lists the recent graduates’ reasons for choosing to volunteer as writing preceptors. The primary reason for participation was an interest in teaching. A responsibility to give back to the profession was also cited by many as a reason for participation, as was the thought that participation as a writing preceptor would improve the graduate’s resume status. Ninety percent or more of the respondents strongly agreed, agreed, or somewhat agreed that their writing preceptor experience was rewarding and that their feedback expanded their students’ knowledge (Table 4). Seventy-seven percent strongly agreed, agreed, or somewhat agreed that the students invested time and effort in the writing assignments. Sixty-two percent of respondents strongly agreed, agreed, or somewhat agreed that students struggled to link specific competencies to their experiential activities.

Table 3.

Recent Graduates’ Reasons for Serving as Writing Preceptors, N = 64

Table 4.

Writing Preceptors’ Opinions Regarding Their Writing Preceptor Experience, N = 64

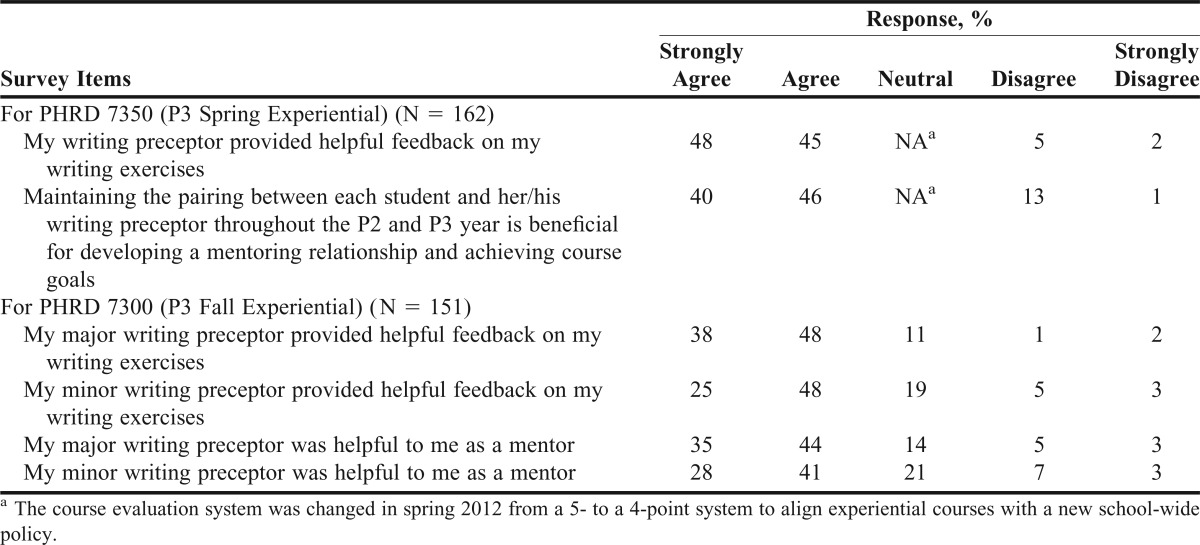

Student opinions regarding the reflective writing program collected anonymously in 2012 as part of routine course evaluation activities (also designated exempt from IRB approval) are presented in Table 5. The majority of students finishing the IPPE program (P3 students) either agreed or strongly agreed that the writing preceptors provided useful feedback and that the maintenance of a one-on-one relationship between a student and writing preceptor over the span of the P2 and P3 years was useful for developing a mentor/mentee relationship and for achieving course goals. Two-thirds or more of P3 students either agreed or strongly agreed that both the major and minor writing preceptors provided helpful feedback and were helpful mentors.

Table 5.

Class of 2013 Students’ Opinions Regarding the Reflective Writing Program

DISCUSSION

A 3-year IPPE reflective writing program within a PharmD program was developed along with a large group of writing preceptors who sustained the program each year for 3 classes of 160 students. The primary goal of the writing program was to improve students’ ability to care for patients by developing their lifelong learning skills. They were required on multiple occasions every semester for 3 years to reflect on their IPPE patient care activities to identify, act on, and evaluate learning opportunities. The primary feature of the writing program was the establishment of 3 long-term mentor/mentee relationships between IPPE students and APPE students, full-time faculty members, and volunteer practitioners. The mentor/mentee nature of the student/writing preceptor relationship allowed the mentors to provide formative feedback on students’ work such that the work can be improved prior to summative assessment.

The increase in the size of the writing preceptor pool is important because it allowed the course directors to reduce their workload as writing preceptors to a sustainable level (each volunteer writing preceptor throughout the early development of the writing program was asked to mentor 5 students which left large numbers of students in the hands of course directors). The increase in the average experience of the writing preceptors is important because it demonstrates an increasing maturity within the writing preceptor pool with respect to both pharmacy practice experience and writing preceptor experience. Writing preceptors who had mentored a group of students through their P2 and P3 years were willing to continue in the program by accepting a new group of P2 students. Nonetheless, it is unreasonable to expect all writing preceptors to participate for indefinite periods of time as their own lives and careers evolve.

Evidence that the writing program develops students’ lifelong learning skills is provided by students’ course grades and by the writing preceptor survey data. A primary grading criterion is that students show progression from one IPPE semester to the next in their ability to identify, act on, and evaluate learning opportunities identified through reflection on past performance; high course pass rates indicate that these outcomes are being achieved. In addition, most of the writing preceptors believed that the IPPE students were meeting course outcomes and were able to apply learning from past experiences to improve future performance. The primary program limitation is that it is not known if the lifelong learning skills developed by the writing program were maintained and applied by graduates in their pharmacy practice careers. The fact that preceptors consistently reported that students struggled to link specific competencies to their experiential activities provides further evidence that reflection is not intuitive.1,5

Evidence that the writing preceptor mentor/student mentee concept is working effectively is provided by the writing preceptor and IPPE student survey data. A majority of students held the opinions that the writing preceptors provided helpful feedback on their writing assignments and that the P2/P3 mentor/mentee relationships were beneficial in achieving course goals. A large majority of the writing preceptors reported that their writing preceptor activities were personally rewarding and that their students put a great deal of effort into their reflective writing assignments.

The writing preceptor survey data suggest the writing program could be reproduced by other colleges and schools of pharmacy. The writing preceptors ranked interest in teaching, keeping a connection with their pharmacy school, and fulfilling a professional obligation high as reasons for participation in the writing program. The writing preceptor program permits any pharmacist with Internet access to participate regardless of the nature and location of their practice and, as such, provides a mechanism for alumni and others to maintain active school involvement beyond traditional workplace supervision of IPPE and APPE students. In addition, the flexibility to provide formative and summative assessment at any time of day on any day of the week is probably an important factor in writing preceptor participation.

The nature of the writing program has evolved in response to experience gained in the early years of the program and growth in the writing preceptor pool. Faculty resources were limited and the level to which IPPE students could perform in practice was unclear when the school’s PharmD degree program began; thus, by necessity, the writing assignments at that time were short, emphasized elements of patient care rather than a detailed comprehensive description and analysis of patient care, and received brief rather than extensive feedback. Colleges and schools of pharmacy that choose to implement an IPPE reflective writing program are encouraged to begin by emphasizing the quality of student writing and preceptor feedback rather than the number of writing assignments. The number of required writing assignments should reflect the number of writing preceptors available and should be increased only as the pool of writing preceptors grows. In addition, deans and department chairs should encourage faculty participation as writing preceptors because reviewing students’ description of their application of knowledge and skills in practice provides insights to faculty members with respect to curricular improvements.

SUMMARY

A required 3-year IPPE reflective writing program aided by a cohort of writing preceptors who support 3 classes of 160 students was successfully implemented and further developed over 8 years. The primary goal of the writing program is to develop students’ lifelong learning skills by requiring them to reflect on their patient care experiences to identify, act on, and evaluate learning opportunities. Successful achievement of that goal is evidenced by high pass rates for students in their IPPE courses and by the opinions of writing preceptors regarding the achievement of course outcomes. The program demonstrates that volunteer pharmacy practitioners can be recruited in large numbers to support a reflective writing program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(4):595–621. doi: 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin Z, Gregory PA, Chiu S. Use of reflection-in-action and self-assessment to promote critical thinking among pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(3):Article 48. doi: 10.5688/aj720348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briceland LL, Hamilton RA. Electronic Reflective Student portfolios to demonstrate achievement of ability-based outcomes during advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(5):Article 79. doi: 10.5688/aj740579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Accreditation Counsel for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Version 2.0. Effective. February 14, 2011. www.acpe-accredit.org/standards/default.asp Accessed October 25th 2012.

- 5.Driessen E, van Tartuijik J, Dornan T. The self-critical doctor: helping students become more reflective. Br Med J. 2008;336(7648):827–830. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39503.608032.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathers NJ, Challis MC, Howe AC, Field NJ. Portfolios in continuing medical education: effective and efficient? Med Educ. 1999;33(7):521–530. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teekman B. Exploring reflective thinking in nursing practice. J Adv Nursing. 2000;31(5):1125–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gustafsson C, Fagerberg I. Reflection, the way to professional development? J Clin Nursing. 2004;13(3):217–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearson d. Heywood P. Portfolio use in general practice vocational training: a survey of GP registrars. Med Educ. 2004;38(1):87–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wald HS, Davis SW, Reis SP, Monroe AD, Borkan JM. Reflecting and reflections: enhancement of medical education curriculum with structured field notes and guided feedback. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):830–837. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a8592f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloom BS, editor. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York, NY: McKay; 1956. [Google Scholar]