Abstract

Despite decades of public health initiatives, tobacco use remains the leading known preventable cause of death in the United States. Clinicians have a proven, positive effect on patients’ ability to quit, and pharmacists are strategically positioned to assist patients with quitting. The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy recognizes health promotion and disease prevention as a key educational outcome; as such, tobacco cessation education should be a required component of pharmacy curricula to ensure that all pharmacy graduates possess the requisite evidence-based knowledge and skills to intervene with patients who use tobacco. Faculty members teaching tobacco cessation-related content must be knowledgeable and proficient in providing comprehensive cessation counseling, and all preceptors and practicing pharmacists providing direct patient care should screen for tobacco use and provide at least minimal counseling as a routine component of care. Pharmacy organizations should establish policies and resolutions addressing the profession’s role in tobacco cessation and control, and the profession should work together to eliminate tobacco sales in all practice settings where pharmacy services are rendered.

Keywords: academic pharmacy, policy, public health, smoking, tobacco

INTRODUCTION

In 1982, US Surgeon General C. Everett Koop stated that cigarette smoking is the “chief, single, avoidable cause of death in our society and the most important public health issue of our time.”1 This statement remains true today, 3 decades later. In the United States, cigarette smoking is the primary known cause of preventable death, resulting in an estimated 443,595 deaths annually.2 Because of smoking, half of all long-term smokers die prematurely;3 for every 1 person who dies because of tobacco use, another 20 suffer with at least 1 tobacco-attributable disease.4

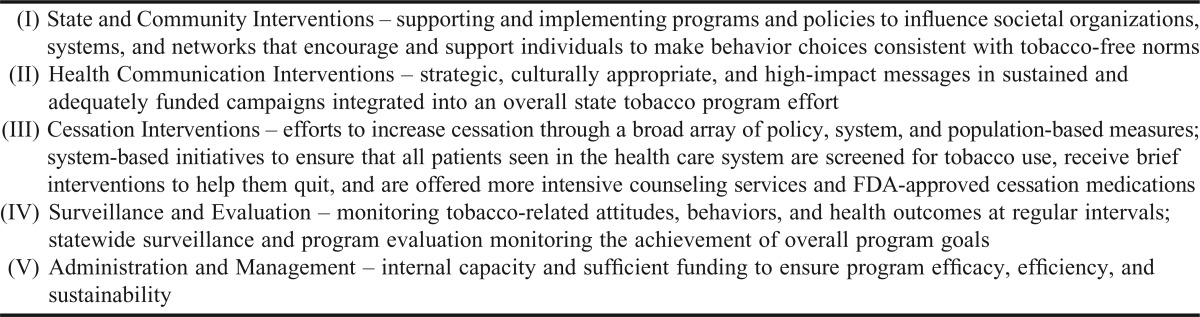

Over the past 50 years, substantial progress has been made toward controlling the tobacco epidemic and reducing the prevalence of smoking in the United States. However, the significant reductions achieved in the 1980s and early 1990s have not continued in recent decades. In 2011, 19% of the adult population reported current smoking.5 In 2010, the tobacco industry spent $8.5 billion (more than $23 million per day) for product advertising and promotion, outspending tobacco prevention funding nationwide by 23 to 1.6,7 In an effort to counteract the tobacco industry influence, and to aid achievement of the Healthy People 2020 goal to reduce the prevalence of smoking to 12%,8 the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) published an evidence-based guide to assist states with establishing effective tobacco control programs. This guide, Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs–2007,9 defines 5 overarching components for population-based approaches (Appendix 1). Although the pharmacy profession and individual pharmacists can play important roles in each of these components, it is the “cessation interventions” component that is most closely aligned with the practice of pharmacy and therefore is most relevant to academic pharmacy.

An estimated 69% of current adult smokers want to stop smoking, and 52% reported having made an attempt to quit in the past year.10 As a key interface between patients and the healthcare community, pharmacists are well positioned to help patients initiate attempts to quit or complement the cessation efforts initiated by other providers. Unlike most other clinicians, advice from a pharmacist does not require an appointment or medical insurance; as such, pharmacists have the opportunity to reach and assist underserved populations, which exhibit a disproportionately higher incidence of tobacco-related diseases.11 Furthermore, because 3 nicotine replacement therapy formulations – the nicotine gum, lozenge, and transdermal patch – are available without a prescription, pharmacists might be the only health professionals with an opportunity to address cessation with these patients prior to or during their attempts to quit.

The concept of pharmacist involvement in tobacco cessation and control activities is not new (readers can obtain a comprehensive listing of relevant citations from the corresponding author). Nearly 3 decades ago, Koop described a “Pharmacists’ Helping Smokers Quit” program in a pharmacy journal.12 While the impact of US pharmacists on quit rates is not well established, preliminary findings appear favorable,13,14 and pharmacists have proven to be cost-effective participants in tobacco cessation programs.15,16 Research consistently shows that pharmacists are interested in providing cessation assistance; 86% of pharmacists17 and 96% of pharmacy students18 believe that the pharmacy profession should be more active in helping patients quit smoking/using tobacco.

In line with the current environment of escalating medical care costs, healthcare reform, and an increased focus on preventive care, all health disciplines and the healthcare system in general must ensure that all patients seen are screened for tobacco use and are offered interventions to help them quit. As such, health degree programs must train their graduates to implement effective, comprehensive evidence-based interventions for cessation.19 Furthermore, organizations representing health professionals should take a more active role in the development and promotion of policies that support tobacco control efforts. Consistent with this goal, members of the Tobacco Control Committee of the Public Health Special Interest Group (SIG) of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) developed the white paper presented herein to characterize the role of and provide key recommendations for academic pharmacy in tobacco cessation and control efforts.

TREATING TOBACCO USE AND DEPENDENCE: EDUCATION FOR THE PHARMACY PROFESSION

Despite the direct link between tobacco use and morbidity and mortality, health professional schools, including but not limited to pharmacy, historically have failed to integrate adequate levels of tobacco cessation education into their core curriculum. In pharmacy colleges and schools,20 the most frequently reported barrier to enhanced tobacco cessation education is lack of available time in the curriculum.

As delineated in the US Public Health Service document, Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence, all clinicians and students in the health professions should be trained in effective strategies to assist tobacco users willing to attempt to quit and to motivate those unwilling to quit.19 The Guideline further recommends that clinicians incorporate a 5-component care model in the delivery of comprehensive tobacco cessation treatment interventions. Known as “the 5 A’s,” these are (1) ask about tobacco use, (2) advise tobacco users to quit, (3) assess readiness to quit (4) assist with quitting, and (5) arrange follow-up care.

While it is well established that counseling from a clinician can approximately double patients’ odds of quitting, and that providers who receive training are more likely to intervene with their patients who use tobacco, few health professionals provide comprehensive tobacco cessation counseling as a routine component of care.19,21 Commonly-cited barriers to providing cessation counseling include time constraints and lack of knowledge and skills. Because of the time pressures in clinical practice, and a general public health movement toward simplifying the burden of tobacco cessation for clinicians,22,23 trends in healthcare provider education advocate that when time constraints or limited expertise preclude provision of comprehensive tobacco cessation counseling, clinicians should apply a truncated 5 A’s model, whereby they ask patients about tobacco use and advise tobacco users to quit. The cessation assistance, which is the more time- and expertise-intensive component of the 5 A’s, is achieved by referring patients to other resources for quitting, such as a tobacco quitline, group program, or web-based cessation program. This brief, minimal approach is known as the Ask-Advise-Refer model. Because most pharmacists are interested in providing cessation services,17 yet few are able to integrate comprehensive tobacco cessation counseling into routine practice,24 brief interventions are inherently appealing for the pharmacy profession and appear to be feasible in the pharmacy practice environment.25-29 If broadly implemented, brief interventions (3 minutes or less)19 could lead to a significant reduction in the national prevalence of tobacco use.

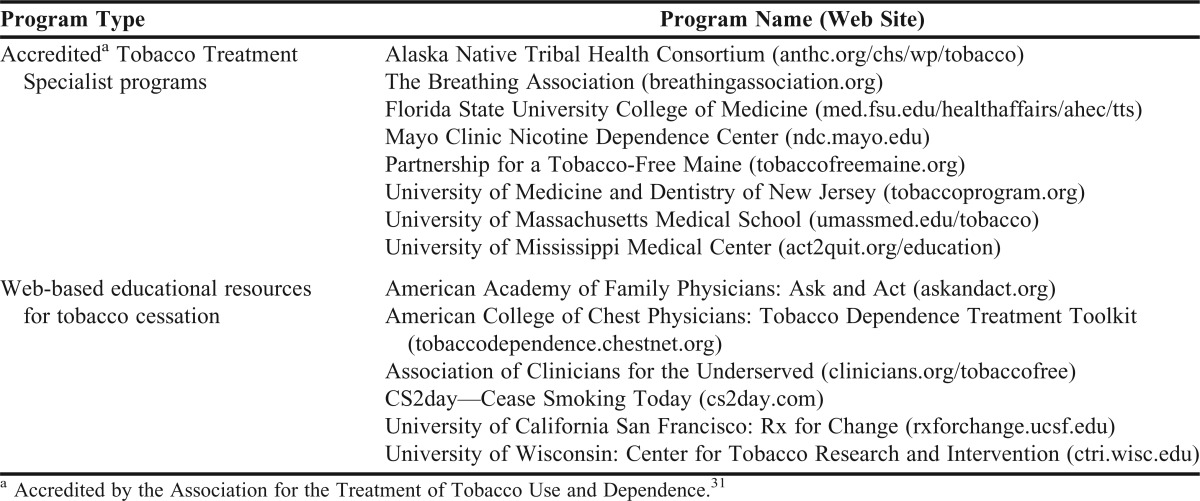

Because of the significant impact of tobacco use on health,30 all healthcare providers should achieve at least minimal competency for tobacco cessation counseling, and cessation education should be a required curricular component in all health professions schools. A variety of training programs and Web-based educational resources (Table 1) are available and relevant to pharmacy students and licensed pharmacists. Options range from comprehensive, multi-day, accredited Tobacco Treatment Specialist (TTS) programs31 to brief-intervention continuing-education webinars designed for busy clinicians. With the exception of the Rx for Change program (Table 1),32 none of the comprehensive tobacco cessation programs are specifically designed for use in colleges and schools of pharmacy.

Table 1.

Tobacco Cessation Training and Educational Resources Relevant to the Pharmacy Profession

To bridge a decades-long gap in tobacco education, efforts are needed to engage and mobilize the current and future healthcare workforce through: (1) education of faculty members and preceptors in health degree programs, (2) integration of tobacco cessation content into health professions curricula, and (3) educational activities directed toward licensed clinicians.33

Faculty Members and Preceptors

Pharmacy faculty members who are responsible for tobacco cessation-related content in the classroom curriculum should, at a minimum, be knowledgeable and proficient in providing comprehensive cessation counseling (eg, the 5 A’s). Faculty members providing instruction on medical conditions caused or exacerbated by tobacco use (eg, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, diabetes, oncology) should, at a minimum, advocate and promote brief tobacco cessation interventions (eg, Ask-Advise-Refer) as an essential component of care. In 2003-2005, a nationwide training initiative was implemented for pharmacy faculty members through grant funding from the National Institutes of Health.34 To foster development of skills for implementing the Rx for Change program, a series of five 2.5-day train-the-trainer programs were offered to 2 faculty members at each school. One hundred ninety-one faculty members participated, representing 98% of the 91 accredited pharmacy programs at the time. Because of faculty turnover/attrition and to develop faculty members at the new colleges and schools of pharmacy, additional training programs are needed. These training sessions or workshops could be provided through a variety of mechanisms, including live webinars hosted by the Public Health SIG, local/regional trainings taught by pharmacy faculty members who have tobacco cessation expertise (eg, Rx for Change-trained faculty members), or as a program or workshop at a national pharmacy conference (eg, AACP annual meeting).

Because experiential education comprises 30% of the professional curriculum, introductory pharmacy practice experience (IPPE) and advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) preceptors play an important role in the integration and application of tobacco cessation counseling in “real world” practice environments. For preceptors who lack the necessary training and skills, experiential education program directors could offer brief (eg, 1-2 hour) continuing education programs as a preceptor development strategy, using evidence-based materials. When relevant and feasible for the practice setting, IPPE and APPE preceptors can apply and reinforce classroom instruction by having students provide tobacco cessation counseling to patients using the 5 A’s.

Pharmacy Students

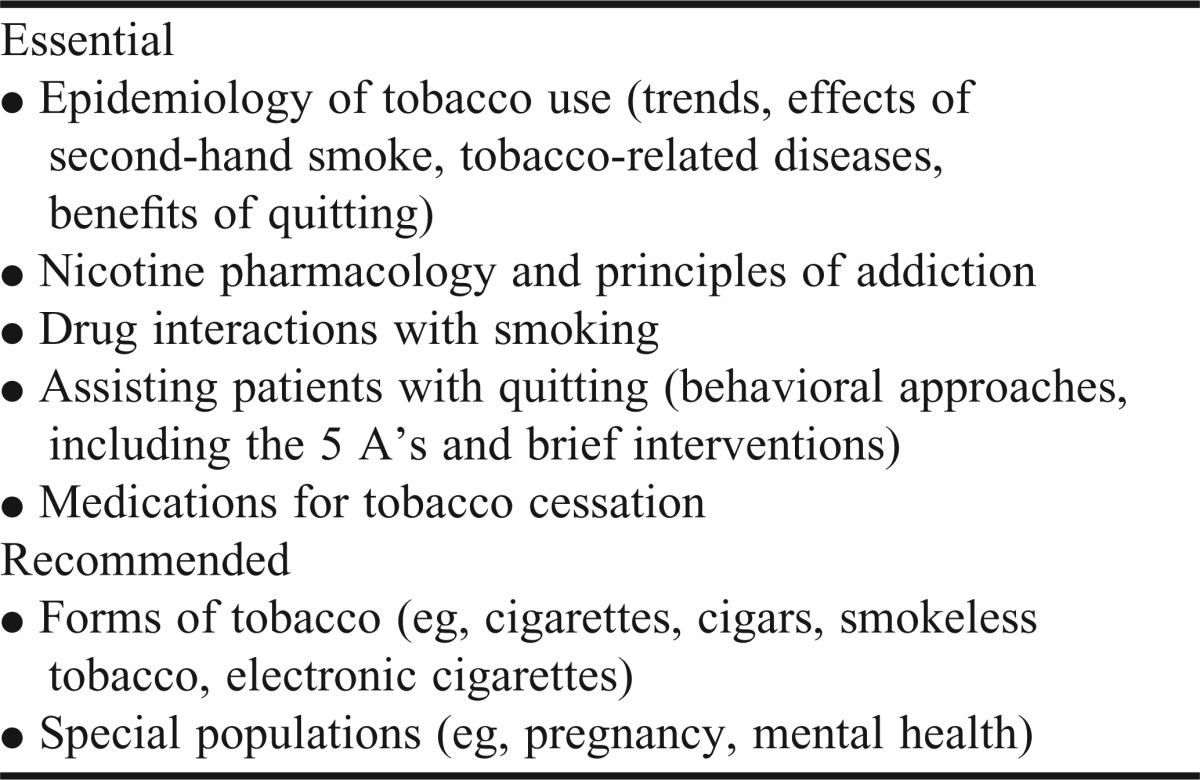

For pharmacists to be recognized as viable tobacco cessation providers, all pharmacy graduates must be equipped with the knowledge and skills to intervene with their patients who use tobacco. As such, all colleges and schools of pharmacy should incorporate comprehensive tobacco cessation training (5 A’s) within the required curriculum. In addition to experiential components, several sources have previously described critical components to be incorporated into the classroom curriculum (Table 2).20,31,32,34,35

Table 2.

Essential and Recommended Components for Tobacco Cessation Education in Pharmacy Curricula32,35

These topics should be initiated early in the curricula of health professional schools to instill the concept of tobacco cessation as an essential element in the treatment and prevention of a wide range of medical conditions.36 Web-based training has been used as a method for enhancing pharmacy students’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and readiness to address tobacco cessation;37,38 however, research is needed to assess the comparative effectiveness of live versus computer-assisted instruction in health professional education.39 Given the scope of content and the complexity of counseling for tobacco dependence, a minimum of 6 hours of training is necessary for students to master the basic 5 A’s approach to counseling, including patient education for cessation medications.36 Inclusion of case-based problem solving, role-playing or videos with case scenarios, and virtual or standardized patients will foster development of self-efficacy, which has been shown to be the primary predictor of the number of patients that pharmacists counsel regarding tobacco cessation.17,40 While 6 hours of training is recommended for mastery, data suggest that 2 hours of lecture in combination with 2 hours of skills workshops (case-based role-playing exercises) can lead to a significant and sustained increase in students’ self-efficacy for providing tobacco cessation counseling.41 In the United States in 2006, the median number of minutes taught in PharmD programs was estimated at 360;36 this amount had more than doubled (from 170 minutes in 2002)20 as a result of the national training initiative described above.34

Experiential courses represent an opportunity to reinforce classroom instruction through the application of tobacco cessation skills in actual patient care settings. Regardless of the practice location, students are likely to encounter tobacco users in the vast majority of IPPE and APPE sites, and cessation activities should be expanded within this part of the curriculum to the furthest extent possible.

Practicing Clinicians

Ideally, all practicing pharmacists would have the necessary time and expertise to integrate comprehensive cessation counseling (5 A’s) into routine practice. However, the majority of pharmacy practitioners lack the time and training to provide this level of service.17,24 As an acceptable alternative, pharmacists in direct patient-care practice settings should receive training in how to conduct brief tobacco cessation interventions using the Ask-Advise-Refer approach. Community pharmacists could increase the number of brief cessation interventions conducted by assessing tobacco use status when creating new or updating existing patient profiles. All practicing pharmacists should promote tobacco avoidance for non-users and apply behavioral and/or pharmacologic methods, as appropriate, among patients who use tobacco.19 While not essential, in selected settings (eg, smoking cessation clinics) or when working with special populations (eg, patients with mental illness), licensed pharmacists should consider additional training. Developing higher-level competencies, such as those achieved by individuals completing accredited TTS training programs (Table 1), requires more in-depth education in combination with practice-based service hours dedicated to tobacco cessation counseling.31 Clinicians completing accredited TTS curricula are well-equipped to serve more complicated patient populations with unique cessation needs, such as those with multiple comorbidities or mental illness.

TOBACCO CONTROL POLICY AND ADVOCACY ISSUES

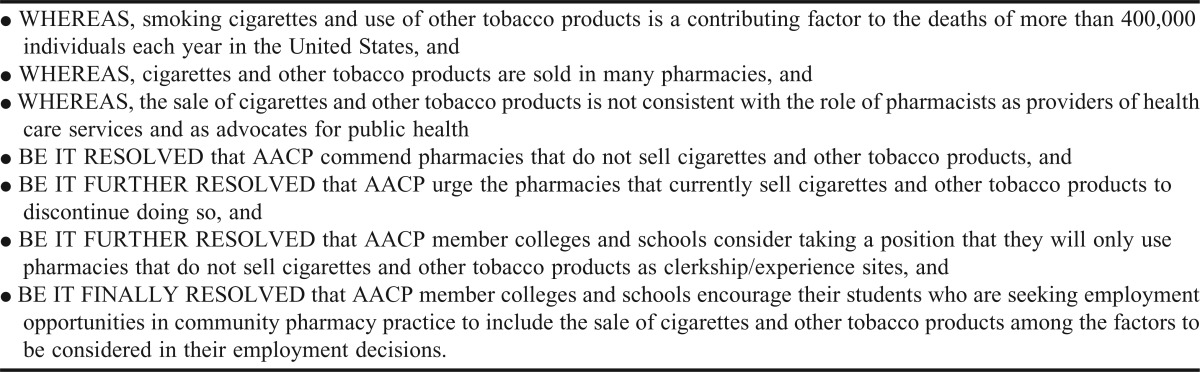

Pharmacists are charged with acting in the best interest of patients’ health as delineated by their code of ethics, which states “a pharmacist promises to help individuals achieve optimum benefit from their medications, to be committed to their welfare, and…avoids…actions that compromise dedication to the best interests of patients.”42 Studies published during the last decade clearly show that few members of the pharmacy profession are in favor of tobacco sales in pharmacies.17,43-46 This position is further evidenced by resolutions set forth by state and national pharmacy organizations,47 including AACP,48 the American Pharmacists Association,49,50 and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists,51 as well as the International Pharmaceutical Federation52 and the American Medical Association.53

Nevertheless, cigarette sales in pharmacies significantly increased (23%) from 2005-2009, accounting for nearly 5% of total US cigarette sales in 2009.54 While there is a clear trend toward elimination of tobacco sales in independently-owned pharmacies,55,56 tobacco sales persist in nearly all retail chain pharmacies, with the exception of a few (eg, Target, Wegmans). Surveys of consumers indicate support for prohibiting the sale of tobacco products in pharmacies,43,57,58 and through the efforts of public health leaders and elected officials, several cities and municipalities (eg, San Francisco, Boston, others) have enacted legislation that prohibits the sale of tobacco products in pharmacies.59-61

Given that the sale of tobacco products contradicts both the clinician’s role in promoting health and the pharmacist’s code of ethics, academic pharmacy should assume a proactive role in advancing policies and legislation that oppose the sale or distribution of tobacco products in all establishments where health care services are rendered (eg, hospitals, clinics, and community pharmacies). This would include policies that (1) discontinue issuance or renewal of licenses for pharmacies that sell tobacco products, and (2) enforce government payer programs to permit only pharmacies that do not sell tobacco products to participate in government-funded prescription programs.50,52 Any regulation on this topic should apply to all entities that operate pharmacies—this would include free-standing entities as well as the stores (eg, grocery stores, big box stores) in which a pharmacy dispensing area is present. Although implementing AACP’s resolution (Appendix 2)48 regarding the exclusive use of tobacco-free experiential training sites might not be possible immediately, the tobacco sales status should be clearly designated for each IPPE and APPE site, and until settings that sell tobacco can be eliminated completely, tobacco-free locations should be assigned priority over ones that sell tobacco.45 Furthermore, individual colleges and schools of pharmacy should consider adopting a policy that endorses legislation and activities that reduce the health burden associated with tobacco use, advances the role of the pharmacy profession in tobacco cessation and control, and opposes the sale of tobacco products in establishments where pharmacy services are rendered.

Although the prevalence of tobacco use among pharmacists is low (<5%),62,63 all pharmacy professionals who currently use tobacco should be offered treatment. Because clinicians who smoke are less likely to intervene with their patients who use tobacco,62 colleges and schools of pharmacy might consider an assessment of tobacco use as part of the admissions process. This information should be used to direct candidates to available cessation services and could be considered as one of the many factors that inform the candidate selection process.

With respect to patient care, academic pharmacy should proactively initiate and support efforts to reduce the prevalence of tobacco use through application of evidence-based practices for cessation as delineated in the Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence.19 This includes supporting policies to ensure that (1) all pharmacy dispensing systems include fields for entering tobacco use status50,64 and screening for potential drug interactions with tobacco smoke,65 (2) nonprescription nicotine replacement therapy products are available at pharmacies, without disparity by race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status of the patient population that they serve,66 and (3) third-party insurers cover costs (counseling and FDA-approved medications for cessation) associated with treating tobacco use and dependence. Academic pharmacy should also promote efforts to improve access to nicotine replacement therapy products, such as making all formulations (including the nicotine inhaler and nasal spray) available without a prescription.

AACP, its members, and state-level pharmacy associations are encouraged to collaborate with state health departments, other healthcare provider organizations, and colleges and schools of pharmacy to promote tobacco control. Advocacy is vital to public health initiatives, and the pharmacy profession must advocate for patients and the profession’s role in tobacco cessation and control as mentioned in the report by the 2010-2011 AACP Standing Committee on Advocacy.67 Unlike other health disciplines, the pharmacy profession has effectively disseminated tobacco cessation training programs across an entire generation of faculty members and students34,36 and therefore is well-equipped to contribute, on multiple levels, to a wide range of initiatives within the CDC’s Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs framework.9 Given the broad accessibility of pharmacists, the pharmacy profession is strategically positioned to reduce the prevalence of tobacco use substantially—particularly among key population groups for which tobacco use is a major risk factor for development or exacerbation of diseases requiring prescription medications (eg, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and diabetes).

CONCLUSION

The adverse effects of tobacco use are well documented, and healthcare professionals have both the responsibility and capacity to significantly reduce the prevalence of tobacco use. Despite the availability of evidenced-based and effective tobacco training programs for current and future healthcare professionals, tobacco use remains a significant public health problem, and a large segment of the pharmacy profession is deficient in their knowledge and skills for assisting patients with quitting. Pharmacy organizations have established policies and resolutions addressing the profession’s role in tobacco cessation and control, but the profession has not effectively integrated these recommendations into practice. The Tobacco Control Committee members of the Public Health SIG of AACP urge academic pharmacy to prioritize tobacco cessation and control, rendering pharmacists as integral members of the public health community.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Valuable external feedback was provided by Daniel Hussar, PhD, Steven Schroeder, MD, Frank Vitale, MA, and Jack Fincham, PhD, RPh. Cindy Tworek, PhD, participated in the manuscript planning process.

Appendix 1.

Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs–2007: CDC-Recommended Components for State Tobacco Control Programs9

Appendix 2.

AACP 2003 Resolution on Tobacco Sales in Pharmacies48

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: Cancer. A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service, Office on Smoking and Health; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses—United States, 2000-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1226–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. Br Med J. 2004;328(7455):1519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking-attributable morbidity—United States, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(35):842–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(44):889–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Spending vs. tobacco company marketing. http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0201.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- 7.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. State-specific estimates of tobacco company marketing expenditures: 1998-2010. http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0271.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2020: tobacco use. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicId=41. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs—2007. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2001-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(44):1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among US Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups - African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koop CE. Pharmacists’ ‘Helping Smokers Quit’ program. Am Pharm. 1986;NS26(7):25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinclair HK, Bond CM, Stead LF. Community pharmacy personnel interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD003698. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003698.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dent LA, Harris KJ, Noonan CW. Tobacco interventions delivered by pharmacists: a summary and systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(7):1040–1051. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.7.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGhan WF, Smith MD. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of smoking-cessation interventions. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1996;53(1):45–52. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/53.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran MT, Holdford DA, Kennedy DT, Small RE. Modeling the cost-effectiveness of a smoking-cessation program in a community pharmacy practice. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(12):1623–1631. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.17.1623.34118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hudmon KS, Prokhorov AV, Corelli RL. Tobacco cessation counseling: pharmacists’ opinions and practices. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(1):152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corelli RL, Kroon LA, Chung EP, et al. Statewide evaluation of a tobacco cessation curriculum for pharmacy students. Prev Med. 2005;40(6):888–895. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudmon KS, Bardel K, Kroon LA, Fenlon CM, Corelli RL. Tobacco education in US schools of pharmacy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(2):225–232. doi: 10.1080/14622200500055392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carson KV, Verbiest ME, Crone MR, et al. Training health professionals in smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD000214. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000214.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonniot Saucedo C, Schroeder SA. Simplicity sells: making smoking cessation easier. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(3 Suppl):S393–S396. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schroeder SA. What to do with a patient who smokes. JAMA. 2005;294(4):482–487. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.482. 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prokhorov AV, Hudmon KS, Marani S, et al. Engaging physicians and pharmacists in providing smoking cessation counseling. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1640–1646. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purcell JL, Farris KB, Aquilino ML. Feasibility of brief smoking cessation intervention in community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2006;46(5):616–618. doi: 10.1331/1544-3191.46.5.616.purcell. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baggarly SA, Jenkins TL, Biglane GC, Smith GW, Smith CM, Blaylock BL. Implementing a referral to telephone tobacco cessation services in Louisiana community pharmacies: a pilot study. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(9):1395–1402. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoch MA, Hudmon KS, Lee L, et al. Pharmacists' perceptions of participation in a community pharmacy-based nicotine replacement therapy distribution program. J Community Health. 2012;37(4):848–854. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9519-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patwardhan PD, Chewning BA. Effectiveness of intervention to implement tobacco cessation counseling in community chain pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2012;52(4):507–514. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2012.10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpenter KM, Carlini BH, Painter I, Mikko AT, Stoner SA. Refer2Quit: Impact of Web-based skills training on tobacco interventions and quitline referrals. J Cont Educ Health Prof. 2012;32(3):187–195. doi: 10.1002/chp.21144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Association for the Treatment of Tobacco Use and Dependence. Core competencies for tobacco treatment specialists. April, 2005. http://attudaccred.org/extras/attud/ATTUD-Core-Competencies.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- 32.Rx for Change: Clinician-Assisted Tobacco Cessation. University of California, San Francisco, Schools of Pharmacy and Medicine. http://rxforchange.ucsf.edu. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- 33.Hudmon KS, Addleton RL, Vitale FM, Christiansen BA, Mejicano GC. Advancing public health through continuing education of health care professionals. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2011;31(Suppl 1):S60–S66. doi: 10.1002/chp.20149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corelli RL, Fenlon CM, Kroon LA, Prokhorov AV, Hudmon KS. Evaluation of a train-the-trainer program for tobacco cessation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(6):Article 109. doi: 10.5688/aj7106109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geller AC, Zapka J, Brooks KR, et al. Tobacco control competencies for US medical students. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(6):950–955. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hudmon KS, Corelli RL, Kroon LA. Kissimmee, FL: July 2012. Dissemination and implementation of a shared tobacco cessation curriculum for pharmacy schools. Presented at: American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Annual Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmelz AN, Nixon B, McDaniel A, Hudmon KS, Zillich AJ. Evaluation of an online tobacco cessation course for health professions students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(2):Article 36. doi: 10.5688/aj740236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maynard A, Metcalf M, Hance L. Enhancing readiness of health profession students to address tobacco cessation with patients through online training. Int J Med Educ. 2012;3:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook DA. If you teach them, will they learn: why medical education needs comparative effectiveness research. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2012;17:305–310. doi: 10.1007/s10459-012-9381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin BA, Bruskiewitz RH, Chewning BA. Effect of a tobacco cessation continuing professional education program on pharmacists’ confidence, skills, and practice-change behaviors. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2010;50(1):9–16. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waheedi M, Al-Tmimy AM, Enlund H. Preparedness for the smoking cessation role among health sciences students in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2011;20(3):237–243. doi: 10.1159/000321273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Pharmacists Association. Code of ethics for pharmacists. http://www.pharmacist.com/code-ethics. Accessed May 26, 2013.

- 43.Hudmon KS, Fenlon CM, Corelli RL, Prokhorov AV, Schroeder SA. Tobacco sales in pharmacies: time to quit. Tob Control. 2006;15(1):35–38. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kotecki JE, Hillery DL. A survey of pharmacists’ opinions and practices related to the sale of cigarettes in pharmacies-revisited. J Community Health. 2002;27(5):321–333. doi: 10.1023/a:1019884526205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hudmon KS, Hussar DA, Fenlon CM, Corelli RL. Pharmacy students’ perceptions of tobacco sales in pharmacies and suggested strategies for promoting tobacco-free experiential sites. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4):Article 75. doi: 10.5688/aj700475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith DM, Hyland AJ, Rivard C, Bednarczyk EM, Brody PM, Marshall JR. Tobacco sales in pharmacies: a survey of attitudes, knowledge and beliefs of pharmacists employed in student experiential and other worksites in Western New York. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:413. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chai T, Karic A, Fairman M, Baez K, Hudmon KS, Corelli RL. Las Vegas, NV: December, 2012. Tobacco and alcohol sales in community pharmacies: Policy statements from US professional pharmacy associations. Presented at: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Midyear Meeting & Exhibition. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leslie SW, Beck DE, Ives TJ, et al. Final Report of the 2002-2003 Bylaws and Policy Development Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article S04. [Google Scholar]

- 49.American Pharmacists Association. Report of the 1971 APhA House of Delegates. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1971;(11):270. NS. [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Pharmacists Association. Current adopted APhA policy statements: 2010 discontinuation of the sale of tobacco products in pharmacies and facilities that include pharmacies. http://www.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/files/HOD_APhA_Policy_Manual_0.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hudmon KS, Corelli RL. ASHP therapeutic position statement on the cessation of tobacco use. Am J Health-System Pharm. 2009;66:291–307. [Google Scholar]

- 52.International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) FIP statement of policy: the role of the pharmacist in promoting a tobacco free future. http://www.fip.org/www/uploads/database_file.php?id=172&table_id=. Accessed May 26, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 53.American Medical Association. Resolutions of the 2009 AMA annual meeting: Banning tobacco product sales in pharmacies. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/hod/a-09-resolutions.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seidenberg AB, Behm I, Rees VW, Connolly GN. Cigarette sales in pharmacies in the USA (2005-2009) Tob Control. 2012;21(5):509–510. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eule B, Sullivan MK, Schroeder SA, Hudmon KS. Merchandising of cigarettes in San Francisco pharmacies: 27 years later. Tob Control. 2004;13(4):429–432. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.007872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corelli RL, Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Kim G, Ambrose PJ, Hudmon KS. Availability of tobacco and alcohol products in Los Angeles community pharmacies. J Community Health. 2012;37(1):113–118. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9424-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kroon LA, Corelli RL, Roth AP, Hudmon KS. Public perceptions of the ban on tobacco sales in San Francisco pharmacies. Tob Control. 2012 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050602. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McDaniel PA, Malone RE. Why California retailers stop selling tobacco products, and what their customers and employees think about it when they do: case studies. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:848. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katz MH. Banning tobacco sales in pharmacies: the right prescription. JAMA. 2008;300(12):1451–1453. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tobacco-free Pharmacies. Tobacco-free Pharmacies: Local Efforts. http://www.tobaccofreerx.org/local_efforts.html. Accessed May 26, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Woodward AC, Henley PP, Wilson DJ. Banning tobacco sales in Massachusetts’ pharmacies. J Am Coll Nutr. 2012;31(3):145–148. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2012.10720020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tong EK, Strouse R, Hall J, Kovac M, Schroeder SA. National survey of U.S. health professionals' smoking prevalence, cessation practices, and beliefs. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(7):724–733. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sarna L, Bialous SA, Sinha K, Yang Q, Wewers ME. Are health care providers still smoking? Data from the 2003 and 2006/2007 Tobacco Use Supplement-Current Population Surveys. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(11):1167–1171. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meyer R, Farris KB, Zillich A, Aquilino M. Documentation of smoking status in pharmacy dispensing software. Am J Health-System Pharm. 2004;61(1):101–102. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kroon LA. Drug interactions with smoking. Am J Health-System Pharm. 2007;64(18):1917–1921. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bernstein SL, Cabral L, Maantay J, et al. Disparities in access to over-the-counter nicotine replacement products in New York City pharmacies. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1699–1704. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coffman RE, Bratberg JP, Flowers SK, et al. Report of the 2010-2011 Standing Committee on Advocacy: leveraging faculty engagement to improve public policy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(10):Article S7. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7510S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]