Abstract

Background:

Fibro-osseous lesions (FOLs) are one of the commonest entities reported in the head and neck region. However, studies on these groups of lesions on Indian population were not carried out before. So this motivated us to analyze the clinico-pathologic correlation of fibro-osseous lesions reported at our hospital.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective review was made of all the lesions surgically treated in our hospital. A total of 6,175 biopsies were performed during the study period. All the cases which were histopathologically diagnosed as FOLs were included in the study. The demographic data, radiographic features, and histopathologic findings were analyzed and compared with similar studies on other races.

Results and Conclusion:

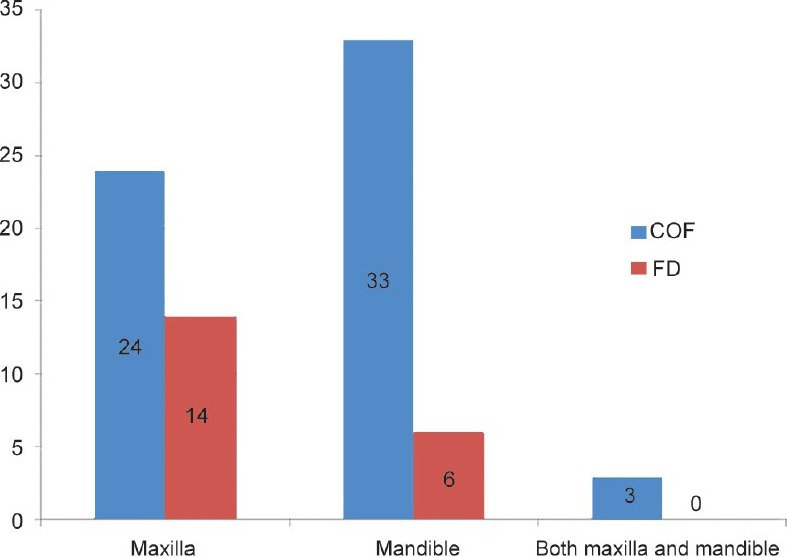

We could find 80 cases diagnosed as fibro-osseous lesions and information about them was documented. The most common FOL reported in the region was cemento-ossifying fibroma (COF) (75%) than fibrous dysplasia (FD) (25%). These were commonly occurring in 2nd decade without any sex or site predilection. However, COF was showing a slight female predominance and FD with a definite male predominance. COF was commonly seen in mandible (posterior region) whereas FD mainly confined to the maxilla (as a whole bone). Radiographically, most of COF showed well-defined mixed opaque and lucent areas whereas FD showed diffuse borders. Cortical plate expansion and resorption of associated teeth was a frequent finding in COF when compared with FD. Histopathologically, stroma was fibrocellular in many cases of COF, whereas most FDs showed fibrous stroma, interspersed with mainly woven bone.

Keywords: Cemento-ossifying fibroma, fibrous dysplasia, fibro-osseous lesions

INTRODUCTION

Fibro-osseous lesions (FOL) are a poorly defined group of lesions affecting the jaws and craniofacial bones. All are characterized by the replacement of bone by cellular fibrous tissue containing foci of mineralization that vary in amount and appearance.[1] Recent World Health Organization classification (2005) for fibro-osseous lesions was considered while sub-dividing these into various groups [Table 1].[2] Diagnosis of these lesions based on histologic appearance alone has considerable limitations.[3] So proper categorization requires good correlation of the history, clinical findings, radiographic characteristics, operative findings, and histologic appearance.[1,3] The aim of this study was to analyze various clinico-pathological and radiological features in the benign FOL reported and to compare the features between fibrous dysplasia (FD) and cemento-ossifying fibroma (COF). These patients were treated for FOL, reported to the hospital between 1989 and 2009.

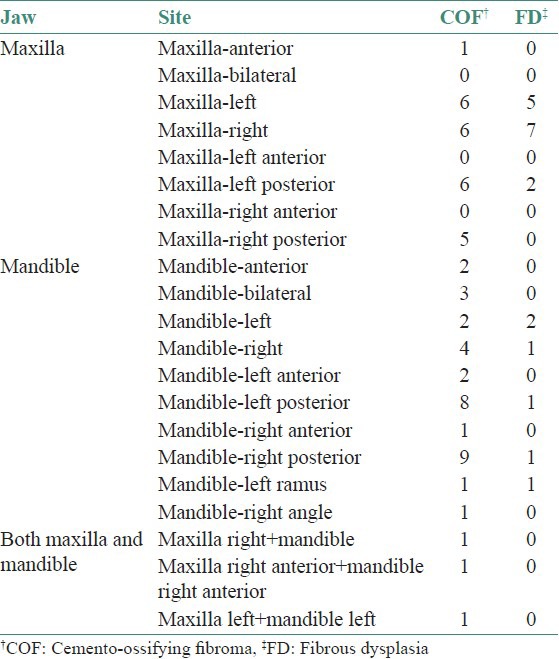

Table 1.

Site distribution of fibro-osseous lesions* depending on the extent

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The sample involved all the cases reported to the hospital. The clinical parameters included were age, sex, location, duration, family history, associated symptoms, and behavior of the lesion. The radiographic appearance, histologic features, treatment, and follow-up data were also recorded. Basic clinical parameters such as age, sex, duration of lesion, family history, history of trauma, associated symptoms, palpatory findings, status of associated/involved teeth, associated pigmentation, site of the lesion, treatment, and recurrence details were retrospectively analyzed.

Regarding site distribution, the maxilla was divided into two anatomic regions as anterior (midline to distal surface of canine) and posterior (mesial surface of first premolar distally). The mandible was divided into four anatomic regions such as anterior (midline to distal surface of canine), posterior (mesial surface of first premolar distally), angle (from distal of third molar to the inferior portion of ramus), and ramus (upper portion of the ramus beyond the occlusal plane).

Radiological features were assessed for radiolucency, radiopacity, margin of the lesion, cortical-plate expansion, involvement of antrum, displacement, and resorption of teeth. Histopathologically, parameters such as type of bone (mature/immature), cellularity, presence of cementum-like material, and nature of stroma were assessed.

RESULTS

Clinical findings

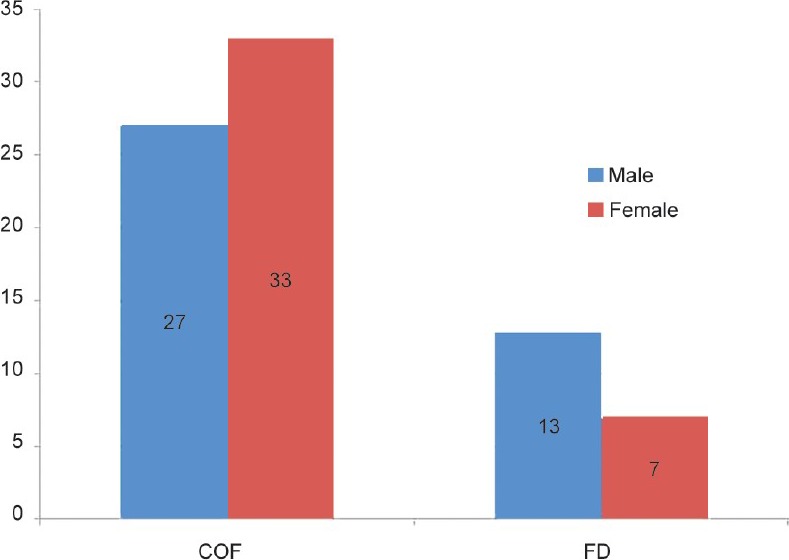

A total of 80 cases of benign FOLs were recorded over the 20 years. Among these, COF (all variants) was the most frequent tumor found in 60 patients with 63 lesions (73.2%) and FD was found in 20 patients (24.4%). In general for FOL, the age ranged from 3 years to 65 years with a mean age of 23.3 years; the majority of COFs and FDs were seen in the second decade (38.3% and 65% respectively). The male-female ratio for these 80 patients was 1:1 with slight female predilection (27 men and 33 women i.e., 1:1.2), whereas FD showed definite male predilection (13 men and 7 women, i.e., 1.8:1). However, there was no significant correlation between the lesions and the sex with P > 0.05 [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The sex distribution of 80 patients with fibro-osseous lesions

Most of the time, FOL patients complained of a slow-growing swelling of the jaws and facial asymmetry (75 patients = 93.7%) whereas in four patients (5%), it was an incidental finding; all these four cases were later diagnosed to be COF. In one case of FD, a biopsy was done because of a non-healing extraction socket.

In case of COF, the associated signs and symptoms involved pus discharge, tenderness, egg shell crackling, tender lymph nodes, ulceration of the overlying mucosa, numbness of lip and proptosis. Few FDs also showed pus discharge, bleeding, proptosis, and blurred vision.

None of family history and past medical history data collected were contributory to our study except few which are listed below. There were four COF patients recorded with history of extraction (2 patients), surgery for osteosarcoma (1 patient), and history of trauma (1 patient) at the site of current presentation.

When FOL as a whole was taken, no specific jaw/side predilection was evident. The COF showed slight mandibular predilection (1.37:1) unlike that of FD which showed definitive maxillary predilection (2.3:1). Moreover, COF were often recorded in mandibular posterior region (51.2%), whereas at the time of presentation FD was recorded unilaterally in maxilla as a whole bone. There were three cases of COF noted at the midline either in maxilla (1 patient) or in mandible (2 patients) and three other cases of COF crossed midline with an extensive presentation in the mandible. The most posterior presentation of COF was noted in two of our cases in the ramus and angle of the mandible [Table 1]. Extensive involvement of facial bones like ethmoidal and frontal bone was seen in FD (2 patients), in four cases of COF {juvenile ossifying fibroma (JOF) variant}, and in two patients with aggressive form of ossifying fibroma (OF) (which cannot be classified as JOF). No pigmentation was evident in any of our cases. When the data was subjected for Chi-square test, significant association was found between the FOL and the site (maxilla and mandible) with P < 0.05 [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

The site distribution of 80 patients with fibro-osseous lesions

Mobility of teeth was seen in 13 patients which included 11 cases of COF and two cases of FDs. In one case of COF, the lesion was associated with displacement of teeth, whereas one COF showed impacted tooth. None of these patients showed any features of skin pigmentation.

Radiological findings

Radiographically, 23 (38.3%) COFs showed mixed opaque and lucent areas, 19 (31.6%) cases showed only radiolucent areas and 18 (30%) cases showed only radiopacity. Among these, 55 (91.6%) had a well-defined border whereas 5 (8.3%) cases were having diffuse outline. Most of these lesions (51.6%) showed expansion of cortical plates. A total of eight COFs, showed involvement of antrum, displacement and resorption of the teeth.

Among FDs, most of them showed mixed opaque and lucent areas (75%), diffuse borders (60%) with only four cases (20%) showing expansion of cortical plates, and five cases showing expansion of antrum. Only one case showed resorption of the associated teeth.

Provisional diagnosis

In case of COF, on 34 (56%) occasions it was provisionally diagnosed as COF and FD was considered in four cases. Among 20 FDs, 15 (75%) times FD was considered as a provisional diagnosis and only in two occasions, it was thought in terms of COF. Other provisional diagnosis considered were adenomatoid odontogenic tumor, ameloblastoma, aneurysmal bone cyst, odontoma, calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor, odontogenic myxoma, central giant cell granuloma, and odontogenic keratocyst for COF and osteoma for FD.

Pathologic findings

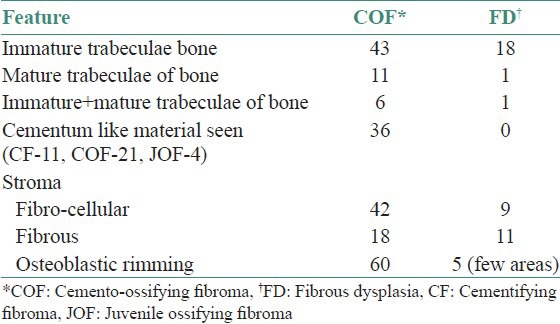

The COF on the post-operative histologic findings was seen as a well-demarcated lesion that was separated from the overlying cortical bone by a thin zone of fibrous tissue. The stroma was fibro-cellular (42 cases) and fibrous (18 cases) with irregular thin trabeculae of woven bone (43 patients) or lamellar bone (11 patients) rimmed by osteoblasts. Basophilic, ovoid, cementum-like material was evident in 21 COFs: Among these four were considered as JOF – psammamatoid type. Other features evident with regular histopathology were the presence of giant cells (5 COF), myxoid areas (1 JOF), and endothelial proliferation (1 COF). FD showed merging of lesional bone with the normal along with highly fibrous stroma (8 cases) consisting of immature trabeculae of woven bone (18 lesions) giving a “Chinese letter” pattern generally without rimming of osteoblasts. Few FDs showed giant cells and myxoid areas [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of histopathological features between cemento-ossifying fibroma and fibrous dysplasia

Treatment and recurrence

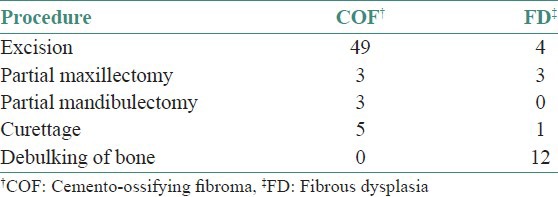

The treatment procedures rendered in these cases has been summarized in the Table 3. Eight patients of COF showed recurrences within a period ranging from 2 months to 4 years. One case of JOF showed three recurrences every year. Among three patients with FDs, two patients had recurrences after 2 and 4 years respectively, with last one showing multiple (3 times) recurrences almost after 3 years each time.

Table 3.

Summary of the treatment rendered to 80 fibro.osseous lesions*

DISCUSSION

The FOL of the jaws comprise a diverse, interesting, and challenging group of conditions that pose difficulties in classification and treatment. Common to all is the replacement of normal bone by a tissue composed of collagen fibers and fibroblasts that contain varying amounts of mineralized substance, which may be bony or cementum-like in appearance.[3] Langdon et al., suggested that certain FOLs of the jaw may represent different stages in the evolution of a single disease process.[4]

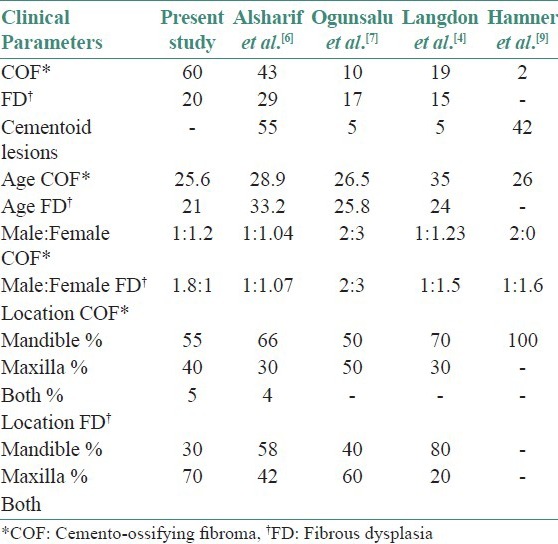

Although the first case report of fibro-osseous lesion was reported 60 years ago,[5] there are only few retrospective studies regarding their clinic-pathological correlation. Among them, the four important studies were carried out by Alsharif et al., on Chinese population,[6] Ogunsalu et al., on Jamican population,[7] Langdon et al., on OFs,[4] and Bustamante et al., has compared clinical and pathologic features of 11 FOL of maxillas.[8] [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of clinical parameters with previous studies

However, although FOL are one of the common lesions occurring in India, such a retrospective study is not reported in the English Language Literature. We also tried to compare the features between COFs and FDs, which are the only two groups of entities reported in this region.

COF is a true benign neoplasm of the bone-forming tissues.[1] Aggressive variants seen in young adults are called as JOF (WHO 1992). According to recent WHO classification of FOLs, OF is a well-demarcated lesion composed of fibrocellular tissue and mineralized material of varying appearances. Juvenile trabecular OF and juvenile psammamatoid OF are two histologic variants of OF.[2] Due to the presence of cementum-like material OF have been called as cementifying fibroma (CF) or COF if they have both cementum and bone-like material.[1]

Previous studies considered cementoid lesions as separate groups which included cemento-osseous dysplasia, gigantiform cementoma, and cementoblastoma.[4,9] However, Alsharif et al.,[6] has considered COF as cementoid lesions containing cementum-like material, since he has considered OF as a separate entity. However, in 1992 the WHO grouped such lesions under the common denomination of COF on the grounds that they represented histologic variants of the same type of lesion.[8]

In this study, OF and COF are combined and no cementoid lesions were reported till today to our hospital. In our data, 24 cases were diagnosed as OF, 21 as COF, 11 as CF, and 4 as JOF. However, we considered all 60 cases as a single entity (COF) in contrast to the study on Chinese population where COF and OF are assessed separately.[6] None of these cases showed any familial history as we know there are two case reports of familial COF.[10,11]

The term FD was given by Lichtenstein in 1938,[12] which was earlier described as osteitis fibrosa disseminate.[13] It is a genetically based sporadic disease of bone that may affect single or multiple bones (monostotic or polyostotic) or if it is occurring in multiple adjacent craniofacial bones, it is regarded as craniofacial FD.[1] FD may be part of Jaffe-Lichenstein's, Macunae Albright's, or Mazabraud's syndrome.[14]

In over 80% of cases it is monostotic,[15] whereas all 20 cases in our data showed a solitary lesion in the jaws, although few of maxillary lesions extending up to infra-orbital margin affect vision. Mean age of occurrence for FD in studies by Zimmerman et al., was 27 years and 34 years, contrasting to what we got as 21 years for the present study.[16]

Radiologically, FD shows a poorly defined lesion that merges with adjacent bone. Early lesions may be radiolucent, but they become increasingly radiopaque and typically show a diffuse radiopacity or “ground glass appearance”.[1] In the present study, 75% of the lesions showed mixed opacity and lucency, whereas two cases were completely radiolucent and three cases with complete radiopaque picture.

The key histologic features of FD are delicate trabeculae of immature bone with no osteoblastic rimming, enmeshed within a fibrous stroma giving a “Chinese letter” pattern.[17] Mature bone was seen in one of our case and osteoblastic rimming was evident in few areas of five cases and stroma was mostly fibrocellular, although few showed a completely fibrous or vascular background.

Compared with previous studies,[4,6–8] both COF and FD were predominantly seen in younger population (25.5 years and 21 years respectively). COF showed a female predilection as seen in previous reports. However, in our data, there was a definite male predilection (1.8:1) for FD which was contrasting to the previous studies.[4,6–8]

When compared with FD, many of COF presented with associated symptoms like pus discharge, egg shell crackling, tenderness, ulceration of the overlying mucosa, numbness of lip, and proptosis which is unusual for these groups of lesions (this involvement was seen in four patients diagnosed as JOF). Other than JOF, there are no previous reports of conventional COF showing highly aggressive behavior. Only few FDs presented with aggressive symptoms. The involvement of other facial bones (frontal, ethmoidal, antrum) was a frequent finding in COF when compared with FD.

CONCLUSION

The findings of the present study showed that there was male predilection in FD. Few of conventional COF were showing unusual aggressive behavior. Both COF and FD showed multiple recurrences. Since few of our COF cases showed history of trauma and association with osteosarcoma, a careful detailing of these in the history is emphasized although its correlation with the occurrence of the lesion cannot be established through this study. As aggressive behavior and recurrence was a frequent finding in few patients with COF, a long follow-up was advised. Osteoblastic rimming was evident in few FDs. Juvenile ossifying fibroma was of predominantly psammamatoid type and finally, not a single cementoid lesion was reported for last 20 years.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Speight PM, Carlos R. Maxillofacial fibro-osseous lesions. Current Diag Pathol. 2006;12:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D. Lyon. France: IARC press; 2005. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumors; pp. 284–327. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldron CA. Fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:249–62. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(85)90283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langdon JD, Rapidis AD, Patel MF. Ossifying Fibroma-one disease or six? An analysis of 39 fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws. Br J Oral Surg. 1976;14:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0007-117x(76)90087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldron CA. Fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:828–35. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alsharif MJ, Sun ZJ, Chen XM, Wang SP, Zhao YF. Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws: A study of 127 Chinese patients and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2009;17:122–34. doi: 10.1177/1066896908318744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogunsalu CO, Lewis A, Doonquah L. Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the jaw bones in Jamaica: Analysis of 32 cases. Oral Dis. 2001;7:155–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vegas Bustamante E, Gargallo Albiol J, Berini Aytés L, Gay Escoda C. Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the maxillas: Analysis of 11 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:e653–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamner JE, 3rd, Scofield HH, Cornyn J. Benign fibro-osseous jaw lesions of periodontal membrane origin. An analysis of 249 cases. Cancer. 1968;22:861–78. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196810)22:4<861::aid-cncr2820220425>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yih WY, Pederson GT, Bartley MH., Jr Multiple familial ossifying fibromas: Relationship to other osseous lesions of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:754–8. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canger EM, Celenk P, Kayipmaz S, Alkant A, Gunhan O. Familial ossifying fibromas: Report of two cases. J Oral Sci. 2004;46:61–4. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.46.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichetenstein L. Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia. Arch Surg. 1938;36:874. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albright F, Butler AM, Hamton AO, Smith P. Syndrome characterized by osteitis fibrosa disseminate, areas of pigmentation and endocrine dysfunction, with precocious puberty in females. New England J Med. 1937;16:727. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, dan Bouquot JE. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd Ed. Philadelphia: W B Saunders Company; 2002. pp. 533–89. [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiCaprio MR, Enneking WF. Fibrous dysplasia. Pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1848–64. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmerman DC, Dahlin DC, Stafne EC. Fibrous dysplasia of the maxilla and mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1958;11:55–68. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(58)90222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brannon RB, Fowler CB. Benign fibro-osseous lesions: A review of current concepts. Adv Anat Pathol. 2001;8:126–43. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]