Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To assess the proportion of youth with type 1 diabetes under the care of pediatric endocrinologists in the United States meeting targets for HbA1c, blood pressure (BP), BMI, and lipids.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Data were evaluated for 13,316 participants in the T1D Exchange clinic registry younger than 20 years old with type 1 diabetes for ≥1 year.

RESULTS

American Diabetes Association HbA1c targets of <8.5% for those younger than 6 years, <8.0% for those 6 to younger than 13 years old, and <7.5% for those 13 to younger than 20 years old were met by 64, 43, and 21% of participants, respectively. The majority met targets for BP and lipids, and two-thirds met the BMI goal of <85th percentile.

CONCLUSIONS

Most children with type 1 diabetes have HbA1c values above target levels. Achieving American Diabetes Association goals remains a significant challenge for the majority of youth in the T1D Exchange registry.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial and Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications study have demonstrated in adolescents and adults that intensive diabetes management significantly reduces the risk of vascular complications in type 1 diabetes (1,2) and that this benefit is sustained over time (3). In addition to glucose control, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity (4–7) increase risk for future vascular disease, and these risk factors can be present in youth with type 1 diabetes. Both the American Diabetes Association (ADA) (8–10) and the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) (11) have established targets for HbA1c, blood pressure (BP), lipids, and BMI for youth with type 1 diabetes. The T1D Exchange clinic registry provides an opportunity to assess the frequencies of youth meeting these targets.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

The T1D Exchange Clinic Network includes 67 United States–based pediatric or adult endocrinology practices. A registry of individuals with type 1 diabetes commenced enrollment in September 2010 (12). Each clinic received approval from an institutional review board (IRB). Informed consent was obtained according to IRB requirements from adult participants and parents or guardians of minors, and assent was obtained from minors. This report includes 13,316 participants from 67 sites enrolled through 1 August 2012, who were younger than 20 years old at enrollment with type 1 diabetes for >1 year.

Data were collected for the registry’s database from the participant’s medical record and by having the participant or parent complete a comprehensive questionnaire (12). A recent HbA1c value (within 6 months before enrollment) was available for 99% (N = 13,226) of participants (82% obtained using DCA, 3% from another point-of-care device, 12% from a laboratory, 3% by an unrecorded method). Data for BP and BMI were available for 12,664 (95%) and 13,045 (98%) participants. Among the 12,639 participants age 6 years or older, fasting LDL, HDL, and fasting triglycerides were available for 2,928 (23%), 8,693 (69%), and 2,387 (19%) participants, respectively (lipid results are not reported for participants age 1 to younger than 6 years because of the small amount of data). Data were categorized according to the following ADA and ISPAD targets: HbA1c (ADA <8.5% for those younger than 6 years of age, <8.0% for those 6 to younger than 13 years of age, and <7.5% for those 13 to younger than 20 years of age; ISPAD ≤7.5% for all ages); BP <90th percentile for age, sex, and height; BMI <85th percentile for age and sex; LDL <100 mg/dL (<2.6 mmol/L); HDL (ADA >35 mg/dL; ISPAD >1.1 mmol/L); and triglycerides <150 mg/dL (<1.7 mmol/L).

The proportion of participants meeting ISPAD and ADA targets for HbA1c, BP, lipids, and BMI were tabulated according to age group. Differences in the characteristics of participants meeting HbA1c targets were evaluated through logistic regression models adjusted for potential confounders. In view of the large sample size, only P < 0.01 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Among the 13,316 pediatric participants, 677 (5%) were 1 to younger than 6 years of age, 5,336 (40%) were 6 to younger than 13 years of age, and 7,303 (55%) were 13 to younger than 20 years of age (mean age, 12.7 years; mean diabetes duration, 5.6 years; 48% female; 78% non-Hispanic white). An insulin pump was used by 55% of participants and a continuous glucose monitor was used by 3%. The median (25th and 75th percentile) number of self-reported self-monitoring of blood glucose per day was 5 (4,7).

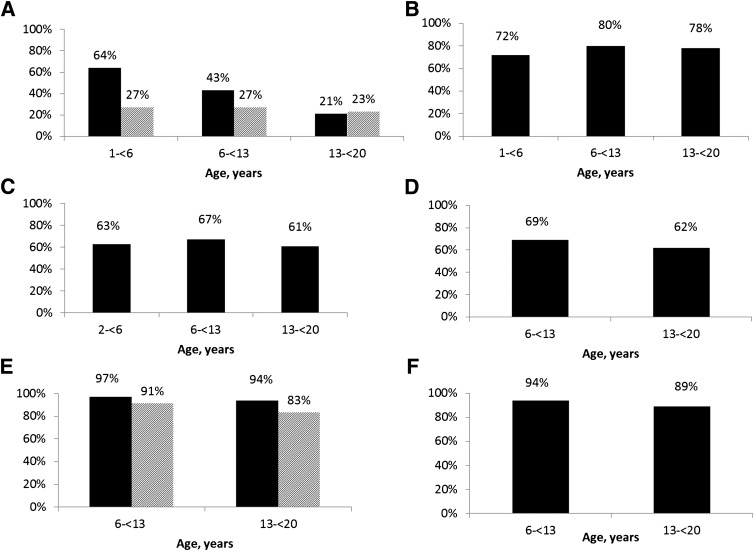

The ISPAD and ADA targets for HbA1c, BP, BMI, and lipids are shown according to age in Fig. 1. Mean ± SD for HbA1c was 8.2 ± 1.1% in those 1 to younger than 6 years old, 8.3 ± 1.2% in those 6 to younger than 13 years old, and 8.8 ±1.7% in those 13 to younger than 20 years old. The age-specific ADA HbA1c target was met by 32% of participants and the ISPAD HbA1c target of ≤7.5% was met by 25% of participants. The percentage meeting ADA and ISPAD HbA1c targets was higher in the younger age groups compared with the group 13 to younger than 20 years old (P < 0.001 for ADA and ISPAD). Among pump users 1 to younger than 6 years old, the proportions of participants meeting the ADA and ISPAD HbA1c targets were 79 and 37% compared with 50 and 17% among injection users (P < 0.001, adjusted for diabetes duration, race/ethnicity, household income, insurance, and self-monitoring of blood glucose per day). In those 6 to younger than 13 years old, 50 and 32% of insulin pump users met the ADA and ISPAD HbA1c targets compared with 34 and 20% of injection users (P < 0.001). There was not a significant difference in the percentage meeting HbA1c targets between insulin pump users and injection users among the group 13 to younger than 20 years old (24 and 27% of pump users vs. 18 and 20% of injection users; P = 0.11 and 0.02). Only 14% of non-Hispanic black participants met the ADA HbA1c target compared with 34 and 28% in non-Hispanic white and Hispanic participants (adjusted P < 0.001). Among participants with available data, 95 and 86% met ADA and ISPAD HDL targets; 78, 63, 65, and 90% met BP, BMI, LDL, and triglycerides targets.

Figure 1.

A: Proportion of participants meeting HbA1c targets (N = 13,226). ADA (black bars): <8.5% for those 1 to younger than 6 years of age, <8.0% for those 6 to younger than 13 years of age, and <7.5% for those 13 to younger than 20 years of age. ISPAD (striped bars): <7.5%. B: Proportion of participants meeting BP target (N = 12,664) <90th percentile for age, sex, and height. C: Proportion of participants meeting BMI target (N = 13,045) <85th percentile for age and sex. BMI percentile was not calculated for those younger than 2 years of age. D: Proportion of participants meeting fasting LDL target (N = 3,010) <100 mg/dL (<2.6 mmol/L). E: Proportion of participants meeting HDL target (N = 8,938). ADA (black bars): >35 mg/dL; ISPAD (striped bars): >1.1 mmol/L. F: Proportion of participants meeting triglycerides target (N = 2,454) <150 mg/dL (<1.7 mmol/L).

CONCLUSIONS

These data from the T1D Exchange describe how frequently ADA and ISPAD targets are met in the largest reported sample (N = 13,316) of youth with type 1 diabetes in the United States. Only approximately one-third of participants met the age-specific ADA and ISPAD targets for HbA1c. Although the majority of participants did meet BP, lipid, and BMI targets, the frequency of abnormalities for these vascular disease risk factors is concerning (13).

Because the clinic registry is not a population-based study, these results may not be representative of all youth with type 1 diabetes. However, participant characteristics were similar to those of patients not enrolled into the registry at the 67 clinics and when compared with the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study (12). Comparisons with DPV German registry are difficult because of differences in target definitions (14). Another limitation is the number of participants missing fasting lipid results and with HbA1c results obtained from point of care.

Despite advances in technologies and strategies for care, achieving HbA1c targets remains a significant challenge for the majority of youth in the T1D Exchange registry. Moreover, a large number of youth with diabetes already have additional vascular disease risk factors at a young age. This analysis suggests further transformations to improve pediatric diabetes care are needed to prevent future complications of diabetes.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

J.R.W. has received consultant payments from Medtronic. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

J.R.W. initiated the idea, wrote the manuscript, contributed to discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. K.M.M. performed statistical analysis, wrote the manuscript, contributed to discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. D.M.M. initiated the idea, wrote the manuscript, contributed to discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. R.W.B. wrote the manuscript, contributed to discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. L.A.D. contributed to discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. I.M.L. contributed to discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.Q. contributed to discussion and reviewed and edited manuscript. W.V.T. contributed to discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. S.E.W. contributed to discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. R.W.B. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

These data were presented in part at the 72nd Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 8–12 June 2012, and at the 2011 International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes Meeting, Miami Beach, Florida, 19–22 October 2011.

Footnotes

A complete list of the members of the T1D Exchange Clinic Network can be found at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/dc12-1959/-/DC1.

References

- 1.The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993;329:977–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, et al. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) Study Research Group Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2643–2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Writing Team for the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group Sustained effect of intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus on development and progression of diabetic nephropathy: the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study. JAMA 2003;290:2159–2167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Libman IM, Pietropaolo M, Arslanian SA, LaPorte RE, Becker DJ. Changing prevalence of overweight children and adolescents at onset of insulin-treated diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:2871–2875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu LL, Lawrence JM, Davis C, et al. SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group Prevalence of overweight and obesity in youth with diabetes in USA: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. Pediatr Diabetes 2010;11:4–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez BL, Dabelea D, Liese AD, et al. SEARCH Study Group Prevalence and correlates of elevated blood pressure in youth with diabetes mellitus: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. J Pediatr 2010;157:245–251, e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahl-Jørgensen K, Larsen JR, Hanssen KF. Atherosclerosis in childhood and adolescent type 1 diabetes: early disease, early treatment? Diabetologia 2005;48:1445–1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverstein J, Klingensmith G, Copeland K, et al. American Diabetes Association Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2005;28:186–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2012. Diabetes Care 2012;35(Suppl. 1):S11–S63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Diabetes Association Management of dyslipidemia in children and adolescents with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:2194–2197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donaghue KC, Chiarelli F, Trotta D, Allgrove J, Dahl-Jorgensen K, International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2006-2007. Microvascular and macrovascular complications. Pediatr Diabetes 2007;8:163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck RW, Tamborlane WV, Bergenstal RM, Miller KM, DuBose SN, Hall CA. The T1D Exchange Clinic Registry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:4383–4389 10.1210/jc.2012-156113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maahs DM. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) limbo: how soon and low should we go to prevent CVD in diabetes? Diabetes Technol Ther 2012;14:449–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbst A, Kordonouri O, Schwab KO, Schmidt F, Holl RW, DPV Initiative of the German Working Group for Pediatric Diabetology Germany Impact of physical activity on cardiovascular risk factors in children with type 1 diabetes: a multicenter study of 23,251 patients. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2098–2100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]