Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Macronutrient “preloads” can reduce postprandial glycemia by slowing gastric emptying and stimulating glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) secretion. An ideal preload would entail minimal additional energy intake and might be optimized by concurrent inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4). We evaluated the effects of a low-energy d-xylose preload, with or without sitagliptin, on gastric emptying, plasma intact GLP-1 concentrations, and postprandial glycemia in type 2 diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Twelve type 2 diabetic patients were studied on four occasions each. After 100 mg sitagliptin (S) or placebo (P) and an overnight fast, patients consumed a preload drink containing either 50 g d-xylose (X) or 80 mg sucralose (control [C]), followed after 40 min by a mashed potato meal labeled with 13C-octanoate. Blood was sampled at intervals. Gastric emptying was determined.

RESULTS

Both peak blood glucose and the amplitude of glycemic excursion were lower after PX and SC than PC (P < 0.01 for each) and were lowest after SX (P < 0.05 for each), while overall blood glucose was lower after SX than PC (P < 0.05). The postprandial insulin-to-glucose ratio was attenuated (P < 0.05) and gastric emptying was slower (P < 0.01) after d-xylose, without any effect of sitagliptin. Plasma GLP-1 concentrations were higher after d-xylose than control only before the meal (P < 0.05) but were sustained postprandially when combined with sitagliptin (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSIONS

In type 2 diabetes, acute administration of a d-xylose preload reduces postprandial glycemia and enhances the effect of a DPP-4 inhibitor.

Therapeutic strategies directed at reducing postprandial glycemia are of fundamental importance in the management of type 2 diabetes (1). For patients with mild-to-moderate hyperglycemia, postprandial blood glucose is a better predictor of HbA1c than fasting blood glucose (2).

Both gastric emptying and the action of the incretin hormones glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) are major determinants of postprandial glucose excursions (3). Gastric emptying determines the rate of nutrient delivery to the small intestine, accounting for approximately one-third of the variation in the initial rise in glycemia after oral glucose in both healthy subjects (4) and those with type 2 diabetes (5). GLP-1 and GIP, released predominantly from the distal and proximal gut, respectively, are the known mediators of the incretin effect, whereby much more insulin is stimulated by enteral compared with intravenous glucose (6). In type 2 diabetes, the incretin effect is impaired (7), related at least partly to a diminished insulinotropic effect of GIP, while that of GLP-1 is preserved (8). In addition, GLP-1 slows gastric emptying (9), suppresses glucagon secretion (10), and reduces energy intake (11). Therefore, incretin-based therapies for diabetes have hitherto focused on GLP-1.

One promising strategy to stimulate endogenous GLP-1 is the “preload” concept, which involves administration of a small load of macronutrient at a fixed interval before a meal so that the presence of nutrients in the small intestine induces the release of gut peptides, including GLP-1, to slow gastric emptying and improve the glycemic response to the subsequent meal. Fat (12) and protein (13) preloads achieve these goals but entail additional energy intake. We recently demonstrated in healthy subjects the potential for poorly absorbed sweeteners, which yield little energy, to stimulate GLP-1 secretion and slow gastric emptying (14).

d-Xylose is a pentose sugar, which is incompletely absorbed by passive diffusion in human duodenum and jejunum (15), with the remainder delivered to the ileum and the colon, where bacterial fermentation occurs, producing hydrogen that can be detected in the breath (16). We recently showed that oral consumption of d-xylose stimulates GLP-1 secretion to a greater and more sustained degree than glucose in healthy older subjects (17), consistent with the principle that the length and region of small intestine exposed to carbohydrate are important determinants of GLP-1 release (18). D-Xylose also slowed gastric emptying compared with water, with efficacy similar to that of the glucose load (17).

Intact GLP-1 is short-lived in the circulation largely because of rapid degradation by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) (19), and orally administered DPP-4 inhibitors, such as sitagliptin, increase postprandial plasma concentrations of intact GLP-1 (20). However, the concept of stimulating endogenous GLP-1 with enteral nutrients and then optimizing its action with a DPP-4 inhibitor has received little attention. Moreover, little consideration has been given as to whether the composition of the diet influences the efficacy of DPP-4 inhibition to lower postprandial blood glucose.

The current study was designed to determine, in patients with type 2 diabetes, whether a d-xylose preload would slow gastric emptying, stimulate GLP-1 secretion, and improve postprandial glycemia and whether these effects could be enhanced by DPP-4 inhibition.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Twelve patients with type 2 diabetes (9 males and 3 females), managed by diet alone, were studied after they had provided written informed consent. The mean ± SE age was 66.2 ± 1.4 years, BMI 28.9 ± 1.0 kg/m2, HbA1c 6.6 ± 0.2% (48.9 ± 2.5 mmol/mol), and duration of known diabetes 4.9 ± 1.1 years. None had significant comorbidities, were smokers, or were taking any medication known to affect gastrointestinal function. The protocol was approved by the human research ethics committee of the Royal Adelaide Hospital and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2000.

Each subject was studied on four occasions, separated by at least 3 days, in randomized double-blind fashion. On the evening before each study day (∼1900 h), each subject consumed a standardized evening meal (McCain’s frozen beef lasagna, 2,170 kJ; McCain Foods Proprietary, Victoria, Australia). At ∼2200 h, subjects took a tablet of either 100 mg sitagliptin (Januvia; Merck Sharp & Dohme) or matching placebo, and compliance was reinforced with a reminder phone call that evening.

Subjects then fasted until the following morning, when they attended the laboratory at ∼0800 h and were seated comfortably for the duration of the study. An intravenous cannula was inserted into an antecubital vein for repeated blood sampling. On each study day, between t = −40 and −38 min, they consumed a 200-mL preload drink containing either 50 g d-xylose or 80 mg sucralose (a control of equivalent sweetness, which we have shown not to stimulate GLP-1 secretion or slow gastric emptying in healthy humans [21,22]), so that the four treatments were sitagliptin plus d-xylose (SX), sitagliptin plus control (SC), placebo plus d-xylose (PX), and placebo plus control (PC). Forty minutes later (between t = 0 and 5 min), they ate a solid meal consisting of 65 g powdered potato (Deb Instant Mashed Potato; Continental, Epping, Australia) and 20 g glucose, reconstituted with 200 mL water and 1 egg yolk containing 100 μL 13C-octanoic acid. Breath samples were collected immediately before and every 5 min after meal ingestion in the first hour and every 15 min for a further 3 h for the measurement of gastric emptying. Venous blood samples and additional breath samples before the preload drink (at t = −40 min) and at t = −20, 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 240 min were taken for the measurements of blood glucose, insulin, intact GLP-1, and breath hydrogen.

Blood samples for insulin were collected in serum tubes. For the measurement of intact GLP-1, venous blood was collected into ice-chilled EDTA tubes containing DPP-4 inhibitor (DPP4-010; Linco Research, St. Charles, MO) (10 μL/mL blood). Samples were mixed six times by gentle inversion and stored on ice before centrifugation at 3,200 rpm for 15 min at 4°C within 15 min of collection. Serum and plasma were separated and stored at –70°C for subsequent analysis.

Blood glucose, serum insulin, and intact GLP-1

Blood glucose concentrations were measured immediately using a glucometer (Medisense Precision QID; Abbott Laboratories, Bedford, MA). The accuracy of the method has been validated against the hexokinase technique (4).

Serum insulin was measured by ELISA immunoassay (cat. no. 10-1113; Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden). The sensitivity of the assay was 1.0 mU/L and the coefficient of variation was 2.1% within assays and 6.6% between assays.

Plasma intact GLP-1 was measured by radioimmunoassay using a commercially available kit (GLP1A-35HK; Millipore, Billerica, MA), which allows quantification of biologically active forms of GLP-1 (i.e., 7-36 amide and 7-37) in plasma and other biological media. The sensitivity was 3 pmol/L, and intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 3.4 and 9.1%, respectively.

Gastric emptying

13CO2 concentrations in breath samples were measured by an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (ABCA 2020; Europa Scientific, Crewe, U.K.) with an online gas chromatographic purification system. The half-emptying time (T50) was calculated, using the formula described by Ghoos et al. (23). This method has been validated against scintigraphy for the measurement of gastric emptying (24).

Breath hydrogen

Hydrogen concentrations in breath samples were measured using Quintron MicroLyzer SC (Quintron Instrument, Milwaukee, WI) and were corrected for CO2 levels (25).

Statistical analysis

The incremental areas under the curve (iAUCs) were calculated using the trapezoidal rule (26) for blood glucose, serum insulin, plasma intact GLP-1, and breath hydrogen and analyzed using one-factor repeated-measures ANOVA. These variables were also assessed by repeated-measures ANOVA, with treatment and time as factors. The amplitude of glycemic excursion (AGE) (postprandial glycemic peak minus the nadir) and J index [J = 0.324 × (mean blood glucose + SD)2] were calculated as measures of glycemic variability, as previously described (27), and these together with gastric emptying (T50) were compared using one-factor ANOVA. Post hoc comparisons, adjusted for multiple comparisons by Bonferroni-Holm correction, were performed if ANOVAs showed significant effects. Relationships between variables were assessed using linear regression analysis. All analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics (version 19.0; IBM, Armonk, NY). Data are presented as means ± SE; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

All subjects tolerated the study well. Three subjects reported mild transient loose stools after completion of the study on the d-xylose days.

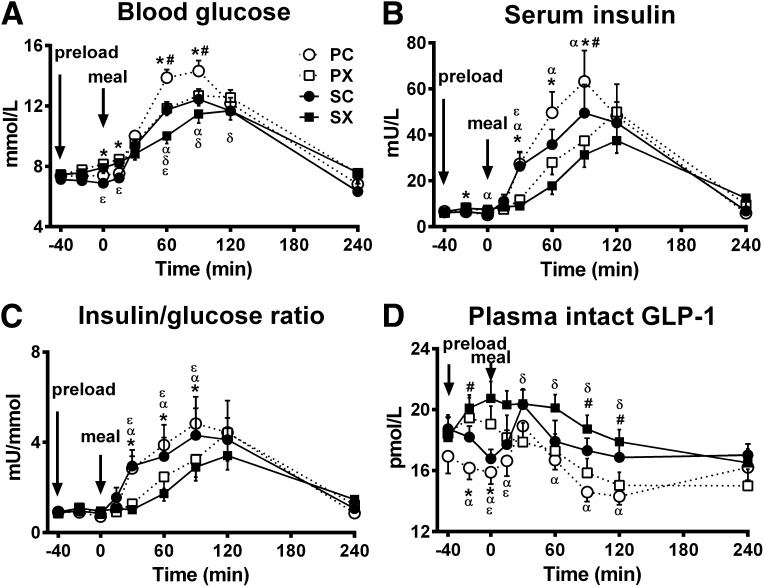

Blood glucose concentrations

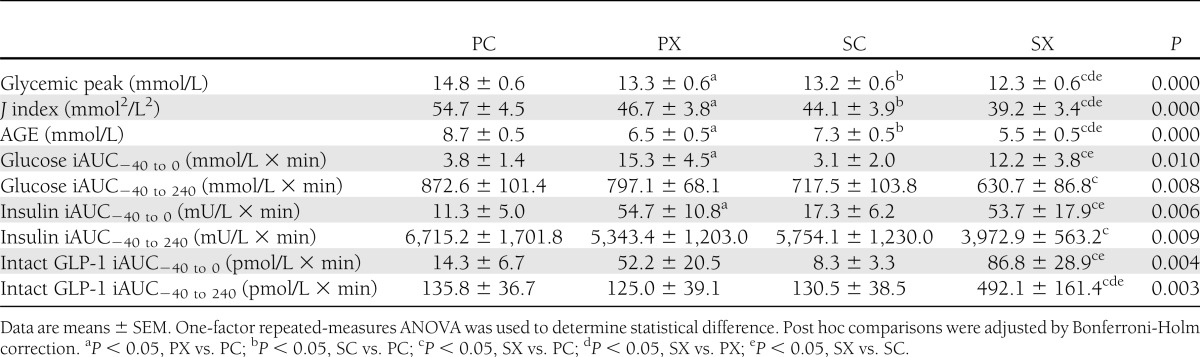

Fasting blood glucose concentrations did not differ between the four study days (PC 7.4 ± 0.3 mmol/L, PX 7.5 ± 0.3 mmol/L, SC 7.1 ± 0.3 mmol/L, and SX 7.5 ± 0.4 mmol/L). Before the meal, blood glucose concentrations increased slightly when the d-xylose preload was given (i.e., PX and SX) in contrast to the control days, so that the iAUC (−40 to 0 min) was greater for PX and SX than for PC and SC (P < 0.05 for each) (Table 1). After the meal, blood glucose concentrations increased on each day before returning to baseline. The postprandial glycemic peak, AGE, and J index were all lower after PX and SC than PC (P < 0.01 for each) and were lowest after SX (P < 0.05 for each) (Table 1). There was a significant treatment effect on the overall iAUC for blood glucose (P = 0.008) (Table 1), such that blood glucose was lower after SX compared with PC (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1A).

Table 1.

Postprandial glycemic peak, J index, AGE, iAUC for blood glucose, serum insulin, and GLP-1 in response to a carbohydrate meal after a preload of either d-xylose or sucralose (control) with or without 100 mg sitagliptin (n = 12)

Figure 1.

Effects of d-xylose or sucralose (control) with or without sitagliptin on blood glucose (A), serum insulin (B), insulin-to-glucose ratio (C), and plasma intact GLP-1 (D) in response to a carbohydrate meal (n = 12). The four treatments were SX, SC, PX, and PC. Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to determine statistical difference. Post hoc comparisons were adjusted by Bonferroni-Holm correction. P = 0.000 for each treatment × time interaction; *P < 0.05, PX vs. PC; #P < 0.05, SC vs. PC; αP < 0.05, SX vs. PC; δP < 0.05, SX vs. PX; εP < 0.05, SX vs. SC. Data are means ± SEM.

Serum insulin

Fasting serum insulin concentrations did not differ between the four study days. Before the meal, insulin concentrations increased slightly when d-xylose was given (i.e., PX and SX) in contrast to the control days, so that the iAUC (−40 to 0 min) was greater for PX and SX than for PC and SC (P < 0.05 for each) (Table 1). After the meal, serum insulin concentrations increased on each day, but d-xylose and sitagliptin alone and in combination resulted in a lower postprandial serum insulin than PC (P = 0.000 for treatment × time interaction, with significant differences at t = 30, 60, and 90 min for PX vs. PC and SX vs. PC; t = 90 min for SC vs. PC; and t = 30 min for SX vs. SC [P < 0.05 for each]). There was also a significant treatment effect on the overall iAUC for serum insulin (P = 0.009) (Table 1), such that insulin concentrations were lower after SX than PC (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1B).

Before the meal, the insulin-to-glucose ratio (Fig. 1C) remained unchanged after both d-xylose and control preloads, but the ratio increased after the meal and was lower from t = 30 to 90 min after the d-xylose preload compared with control (P = 0.000 for a treatment × time interaction: PX vs. PC and SX vs. SC [P < 0.05 for each]) without any effect of sitagliptin.

Plasma intact GLP-1

Fasting plasma intact GLP-1 concentrations did not differ between the four study days. Before the meal, GLP-1 concentrations increased when the d-xylose preload was given, so that the iAUC (−40 to 0) was greater for SX than for PC and SC (P < 0.05 for each) (Table 1), although the difference between PX and PC was not significant. After the meal, intact GLP-1 increased on the control days, but the combination of the d-xylose preload with sitagliptin resulted in more sustained elevation of plasma intact GLP-1 than on the other days (P = 0.000 for a treatment × time interaction, with significant differences at t = 15, 60, 90, and 120 min for SX vs. PC and during t = 30–120 for SX vs. PX [P < 0.05 for each]). There was also a treatment effect on the overall iAUC for plasma intact GLP-1 (P = 0.003) (Table 1), such that GLP-1 was greatest after SX (SX vs. PC, PX, and SC, P < 0.05 for each) (Fig. 1D).

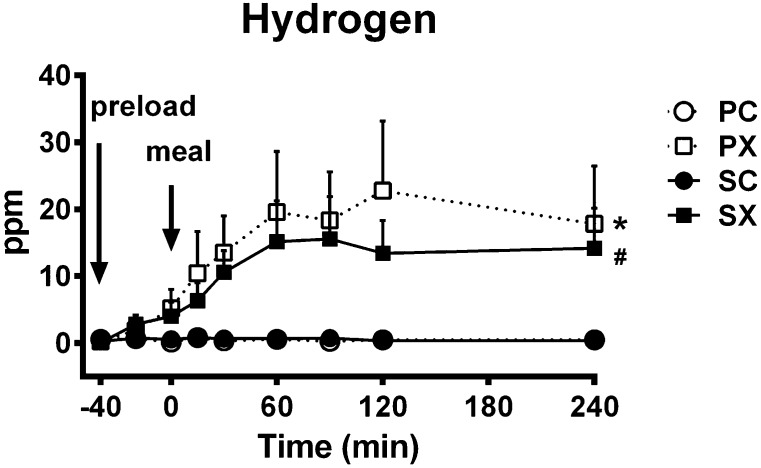

Breath hydrogen production

Fasting breath hydrogen approximated 0 ppm and did not differ between the four study days. After the d-xylose drink, breath hydrogen increased slightly before the meal (t = −40 to 0 min) and continued to rise to a plateau afterward, while it remained unchanged after the control preload and was unaffected by sitagliptin (P = 0.000 for a treatment × time interaction) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of d-xylose or sucralose (control) with or without sitagliptin on breath hydrogen production in response to a carbohydrate meal (n = 12). The four treatments were SX (■), SC (●), PX (), and PC (○). Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to determine statistical difference. *P = 0.000, PX vs. PC and SC; #P = 0.000, SX vs. PC and SC. Data are means ± SEM.

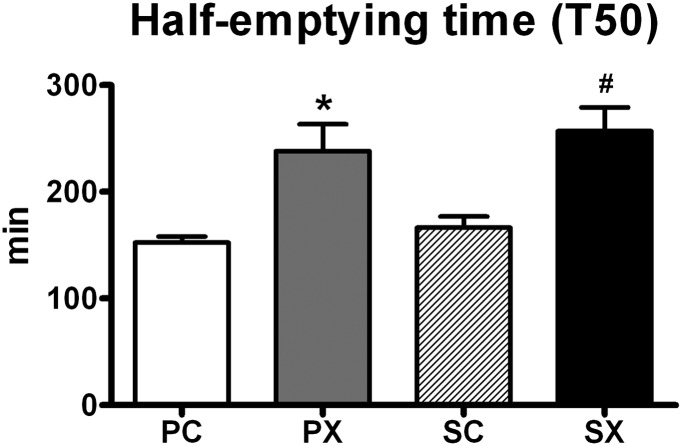

Gastric emptying

There was a treatment effect for gastric emptying (P = 0.000), such that the half-emptying time was greater after d-xylose than control (T50 for PX 238.2 ± 26.4 min and SX 256.9 ± 23.1 min vs. PC 152.3 ± 6.0 min and SC166.3 ± 11.0 min [P < 0.01 for each]) without any effect of sitagliptin (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of d-xylose or sucralose (control) with or without sitagliptin on gastric emptying (half-emptying time [T50]) (n = 12). The four treatments were SX, SC, PX, and PC. One-factor repeated-measures ANOVA was used to determine statistical difference. Post hoc comparisons were adjusted by Bonferroni-Holm correction. P = 0.000 for a treatment effect; *P < 0.01, PX vs. PC and SC; #P < 0.001, SX vs. PC and SC. Data are means ± SEM.

Relationships between blood glucose and gastric emptying, plasma intact GLP-1, and breath hydrogen production

When data from the four study visits were pooled, the magnitude of the postprandial rise in blood glucose from baseline at t = 30, 60, and 90 min was inversely related to the T50 (P < 0.01 for each) and at t = 240 min directly related to the T50 (P = 0.001).

Given that plasma intact GLP-1 would be more sensitive as a measure of GLP-1 secretion when DPP-4 was inhibited, data from the SX day alone were examined for a relationship between breath hydrogen production and GLP-1 secretion. Intact GLP-1 concentrations were found to be related directly to breath hydrogen production (for iAUC−40 to 0, r = 0.72, P = 0.009; for iAUC−40 to 240, r = 0.74, P = 0.006).

CONCLUSIONS

The main observations made in this study of patients with type 2 diabetes managed by diet were that 1) consumption of the low-energy pentose d-xylose in advance of a high-carbohydrate meal attenuates the postprandial glycemic excursion in association with stimulation of GLP-1 secretion before the meal and slowing of gastric emptying, 2) a single dose of the DPP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin increases postprandial intact GLP-1 concentrations and reduces postprandial glycemia without slowing gastric emptying or stimulating postprandial insulin secretion, and 3) the combination of a d-xylose preload with sitagliptin reduces the postprandial glycemic excursion more than either treatment alone. The magnitude of the reduction in postprandial blood glucose achieved by the combination of d-xylose preload and sitagliptin in our group of patients with well-controlled type 2 diabetes was substantial (i.e., reduction in peak blood glucose of ∼2.5 mmol/L), and moreover, there was a marked reduction in indices of glycemic variability; the latter is associated with oxidative stress and may independently increase cardiovascular risk (27).

We chose d-xylose as the preload, since it is incompletely absorbed and poorly metabolized (16) and, accordingly, additional energy intake is minimized in contrast to preloads such as fat (12) and protein (13). Consistent with our previous report in healthy older subjects (17), ingestion of d-xylose resulted in a modest increase in blood glucose and serum insulin, possibly as a result of enhanced gluconeogenesis. Sucralose was selected as a sweet-tasting negative control, since we have shown that this artificial sweetener when given acutely has no effect on either the secretion of GLP-1 or gastric emptying (21,22), and indeed in the current study, there was no increase in intact GLP-1 before the meal on the days when sucralose was given. The osmolarity of the preloads could not readily be matched without changing the taste and this may have contributed to the effect of the d-xylose preload on gastric emptying (28) but is unlikely to account for differences in GLP-1 secretion (22).

As expected, d-xylose was associated with stimulation of GLP-1 in advance of the meal. It has been postulated that intestinal fermentation to form free fatty acids represents an important mechanism for the stimulation of GLP-1 release (29); the latter could be indirectly quantified by resultant hydrogen production in breath samples (16). Our demonstration of a relationship between GLP-1 concentrations and hydrogen production is consistent with this concept. However, the fact that GLP-1 concentrations began to increase within 20 min of d-xylose ingestion suggests that other mechanisms, involving, for example, the passage of d-xylose through the monosaccharide transporters GLUT2 and GLUT3 (30), are likely involved. It may appear surprising that plasma intact GLP-1 levels after the potato meal did not differ between the d-xylose and control preload study days, when sitagliptin was not given. However, the magnitude of GLP-1 secretion is dependent on the rate (31) and load (32) of nutrient entry to the small intestine, so that the slowing of gastric emptying induced by the d-xylose preload may well have attenuated the component of the postprandial GLP-1 response attributable to the meal.

We observed that the magnitude of the initial postprandial glycemic excursion was inversely related to the gastric half-emptying time, consistent with evidence that the rate of gastric emptying is a major determinant of postprandial glycemia (4,5). In the absence of sitagliptin, the reduction in postprandial glycemia by d-xylose is probably attributable mainly to the slowing of gastric emptying, since postprandial intact GLP-1 concentrations were no greater than on the control day. The observed decrease in postprandial insulin concentrations after d-xylose in contrast to control, particularly when corrected for differences in blood glucose (i.e., the insulin-to-glucose ratio), is consistent with what would be expected when gastric emptying of the potato meal is slower (12).

The slowing of gastric emptying after the d-xylose preload was associated with stimulation of GLP-1 in advance of the meal, although postprandial intact GLP-1 concentrations were not increased in the absence of sitagliptin. Since endogenous GLP-1 is known to slow gastric emptying (9), the elevated GLP-1 may have contributed to the slower gastric emptying after d-xylose, at least during the initial phase. Nevertheless, the combination with sitagliptin, which increased plasma concentrations of intact GLP-1, had no additional effect on the rate of gastric emptying—a finding that is consistent with our recent report of the lack of effect of 2-day dosing with sitagliptin on gastric emptying (33). This is likely to be because gastric emptying is modulated by multiple mechanisms. For example, acute hyperglycemia, even within the physiological range, is known to slow gastric emptying (34), and sitagliptin, particularly when combined with d-xylose, potently decreased postprandial glycemia. Moreover, peptide YY (PYY), which is cosecreted with GLP-1 from enteroendocrone L cells, has the capacity to slow gastric emptying. PYY 1-36 and 3-36 are the predominant biologically active forms in the circulation; the latter is formed from degradation of PYY 1-36 by DPP-4 and is reportedly more potent at retarding emptying (35). Therefore, DPP-4 inhibition might, to some extent, blunt PYY- mediated slowing of gastric emptying.

In contrast, addition of sitagliptin did not affect gastric emptying but was associated with lowering of postprandial glycemia. Despite the fact that plasma intact GLP-1 concentrations were increased after sitagliptin, particularly when given in combination with d-xylose, the insulin response to the meal did not increase in parallel. This is partly accounted for by the fact that the insulinotropic effect of GLP-1 is glucose dependent (36), but there is also evidence that mechanisms other than insulin secretion are likely to be important in mediating the glucose-lowering effect of GLP-1; the latter include suppression of both glucagon secretion and endogenous glucose production (37,38) and enhancement of peripheral glucose uptake (39).

It is noteworthy that there has been little consideration of how dietary intake interacts with the actions of DPP-4 inhibitors. The current study is therefore novel in demonstrating how consumption of a specific nutrient can improve the efficacy of a DPP-4 inhibitor for reducing postprandial glycemia. Although the number of subjects studied was relatively small, the observed effects were consistent between subjects and were in keeping with previous observations relating to the slowing of gastric emptying by d-xylose (17) and glucose lowering by sitagliptin (20). Our study represents an acute intervention in a relatively well-controlled group of patients with type 2 diabetes managed by diet alone. In view of the positive outcomes, it would be of particular interest to investigate this approach in type 2 diabetic patients taking metformin, given the synergistic effect of DPP-4 inhibitors with metformin for increasing intact GLP-1 and improving glycemia (40), and to extend our observations to larger and more diverse groups of type 2 diabetic patients over a longer duration.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant awarded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (grant no. 627139).

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

T.W. was involved in study design and coordination, subject recruitment, data collection and interpretation, statistical analysis, and drafting of the manuscript; critically reviewed the manuscript; and approved the publication of the final version of the manuscript. M.J.B. assisted with data collection and breath hydrogen analysis, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the publication of the final version of the manuscript. B.R.Z. assisted in data collection, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the publication of the final version of the manuscript. S.D.S. performed insulin and intact GLP-1 assays, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the publication of the final version of the manuscript. M.B. performed the gastric emptying analysis, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the publication of the final version of the manuscript. K.L.J. and M.H. were involved in conception of the study and data interpretation, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the publication of the final version of the manuscript. C.K.R. was involved in conception and design of the study and data analysis and interpretation, had overall responsibility for the study, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the publication of the final version of the manuscript. C.K.R. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Parts of this study were presented in abstract form at the Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Berlin, Germany, 1–5 October 2012.

The authors thank K. Lange for expert statistical advice and A. Lam (Royal Adelaide Hospital Pharmacy) for assistance in preparation and blinding of the treatments.

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no. ACTRN12612001131842, www.anzctr.org.au.

References

- 1.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia 2012;55:1577–1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Kebbi IM, Ziemer DC, Cook CB, Gallina DL, Barnes CS, Phillips LS. Utility of casual postprandial glucose levels in type 2 diabetes management. Diabetes Care 2004;27:335–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaikomin R, Rayner CK, Jones KL, Horowitz M. Upper gastrointestinal function and glycemic control in diabetes mellitus. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:5611–5621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horowitz M, Edelbroek MA, Wishart JM, Straathof JW. Relationship between oral glucose tolerance and gastric emptying in normal healthy subjects. Diabetologia 1993;36:857–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones KL, Horowitz M, Carney BI, Wishart JM, Guha S, Green L. Gastric emptying in early noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Nucl Med 1996;37:1643–1648 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holst JJ, Vilsbøll T, Deacon CF. The incretin system and its role in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2009;297:127–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nauck M, Stöckmann F, Ebert R, Creutzfeldt W. Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 1986;29:46–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nauck MA, Heimesaat MM, Orskov C, Holst JJ, Ebert R, Creutzfeldt W. Preserved incretin activity of glucagon-like peptide 1 [7-36 amide] but not of synthetic human gastric inhibitory polypeptide in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 1993;91:301–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deane AM, Nguyen NQ, Stevens JE, et al. Endogenous glucagon-like peptide-1 slows gastric emptying in healthy subjects, attenuating postprandial glycemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schirra J, Göke B. The physiological role of GLP-1 in human: incretin, ileal brake or more? Regul Pept 2005;128:109–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Silva A, Salem V, Long CJ, et al. The gut hormones PYY 3-36 and GLP-1 7-36 amide reduce food intake and modulate brain activity in appetite centers in humans. Cell Metab 2011;14:700–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gentilcore D, Chaikomin R, Jones KL, et al. Effects of fat on gastric emptying of and the glycemic, insulin, and incretin responses to a carbohydrate meal in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:2062–2067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma J, Stevens JE, Cukier K, et al. Effects of a protein preload on gastric emptying, glycemia, and gut hormones after a carbohydrate meal in diet-controlled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1600–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu T, Zhao BR, Bound MJ, et al. Effects of different sweet preloads on incretin hormone secretion, gastric emptying, and postprandial glycemia in healthy humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:78–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fordtran JS, Soergel KH, Ingelfinger FJ. Intestinal absorption of D-xylose in man. N Engl J Med 1962;267:274–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craig RM, Ehrenpreis ED. D-xylose testing. J Clin Gastroenterol 1999;29:143–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanis L, Hausken T, Gentilcore D, et al. Comparative effects of glucose and xylose on blood pressure, gastric emptying and incretin hormones in healthy older subjects. Br J Nutr 2011;105:1644–1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qualmann C, Nauck MA, Holst JJ, Orskov C, Creutzfeldt W. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (7-36 amide) secretion in response to luminal sucrose from the upper and lower gut. A study using alpha-glucosidase inhibition (acarbose). Scand J Gastroenterol 1995;30:892–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drucker DJ, Nauck MA. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2006;368:1696–1705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahrén B. DPP-4 inhibitors. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;21:517–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma J, Bellon M, Wishart JM, et al. Effect of the artificial sweetener, sucralose, on gastric emptying and incretin hormone release in healthy subjects. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2009;296:G735–G739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma J, Chang J, Checklin HL, et al. Effect of the artificial sweetener, sucralose, on small intestinal glucose absorption in healthy human subjects. Br J Nutr 2010;104:803–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghoos YF, Maes BD, Geypens BJ, et al. Measurement of gastric emptying rate of solids by means of a carbon-labeled octanoic acid breath test. Gastroenterology 1993;104:1640–1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chew CG, Bartholomeusz FD, Bellon M, Chatterton BE. Simultaneous 13C/14C dual isotope breath test measurement of gastric emptying of solid and liquid in normal subjects and patients: comparison with scintigraphy. Nucl Med Rev Cent East Eur 2003;6:29–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones HF, Burt E, Dowling K, Davidson G, Brooks DA, Butler RN. Effect of age on fructose malabsorption in children presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011;52:581–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolever TM. Effect of blood sampling schedule and method of calculating the area under the curve on validity and precision of glycaemic index values. Br J Nutr 2004;91:295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Standl E, Schnell O, Ceriello A. Postprandial hyperglycemia and glycemic variability: should we care? Diabetes Care 2011;34(Suppl. 2):S120–S127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barker GR, Cochrane GM, Corbett GA, Hunt JN, Roberts SK. Actions of glucose and potassium chloride on osmoreceptors slowing gastric emptying. J Physiol 1974;237:183–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu T, Rayner CK, Jones K, Horowitz M. Dietary effects on incretin hormone secretion. Vitam Horm 2010;84:81–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naula CM, Logan FJ, Wong PE, Barrett MP, Burchmore RJ. A glucose transporter can mediate ribose uptake: definition of residues that confer substrate specificity in a sugar transporter. J Biol Chem 2010;285:29721–29728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaikomin R, Doran S, Jones KL, et al. Initially more rapid small intestinal glucose delivery increases plasma insulin, GIP, and GLP-1 but does not improve overall glycemia in healthy subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2005;289:E504–E507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pilichiewicz AN, Chaikomin R, Brennan IM, et al. Load-dependent effects of duodenal glucose on glycemia, gastrointestinal hormones, antropyloroduodenal motility, and energy intake in healthy men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2007;293:E743–E753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens JE, Horowitz M, Deacon CF, Nauck M, Rayner CK, Jones KL. The effects of sitagliptin on gastric emptying in healthy humans - a randomised, controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;36:379–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schvarcz E, Palmér M, Aman J, Horowitz M, Stridsberg M, Berne C. Physiological hyperglycemia slows gastric emptying in normal subjects and patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology 1997;113:60–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witte AB, Grybäck P, Holst JJ, et al. Differential effect of PYY1-36 and PYY3-36 on gastric emptying in man. Regul Pept 2009;158:57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holst JJ, Gromada J. Role of incretin hormones in the regulation of insulin secretion in diabetic and nondiabetic humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2004;287:E199–E206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prigeon RL, Quddusi S, Paty B, D’Alessio DA. Suppression of glucose production by GLP-1 independent of islet hormones: a novel extrapancreatic effect. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2003;285:E701–E707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muscelli E, Casolaro A, Gastaldelli A, et al. Mechanisms for the antihyperglycemic effect of sitagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:2818–2826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edgerton DS, Johnson KM, Neal DW, et al. Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 by vildagliptin during glucagon-like Peptide 1 infusion increases liver glucose uptake in the conscious dog. Diabetes 2009;58:243–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Migoya EM, Bergeron R, Miller JL, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors administered in combination with metformin result in an additive increase in the plasma concentration of active GLP-1. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2010;88:801–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]