The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates which drugs can be marketed in the U.S. as well as their label requirements. A congressionally authorized advisory committee process allows the FDA to receive input from outside experts on important regulatory decisions (1). Further, the advisory committee process enhances transparency by allowing the public, including health care professionals, to understand the issues being considered. The Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee (EMDAC) “reviews and evaluates data concerning the safety and effectiveness of marketed and investigational human drug products for use in the treatment of endocrine and metabolic disorders, and makes appropriate recommendations to the Commissioner of Food and Drugs” (2). Operationally, the FDA’s Division of Metabolism and Endocrinology Products (DMEP) is responsible for the review of most drugs used for indications relevant to endocrinologists and coordinates the EMDAC’s meetings.

In recent years, the EMDAC has been asked to review a number of controversial drugs, particularly those for the treatment of diabetes and obesity. Often the assessment of these drugs requires integration of preclinical and clinical data to formulate a benefit-risk assessment. The assessment of benefit-risk for drugs is increasingly recognized to be a challenging task, and formal tools have been proposed to make this process more effective (3–7). In contrast with the DMEP and other FDA staff, most EMDAC members will have limited experience in these types of integrative, complex evaluations. Further, EMDAC members will spend considerably less time evaluating the available data in comparison with DMEP staff. Thus, it seems important to compare the recommendations made by EMDAC with the subsequent marketing and label decisions to assess concordance between the evaluative approaches used by EMDAC and that of DMEP (DMEP will be used as shorthand for the full FDA’s involvement in regulatory decisions).

At most of the EMDAC meetings, the committee is asked to vote on a benefit-risk recommendation or other specific questions. These votes reflect the best overall EMDAC position on the issue and are widely cited in the press as the meeting’s primary outcome. This interpretation is overly simplistic as the committee’s discussions and rationales for its votes may be highly informative to DMEP deliberations and have greater importance than the votes (8). Nonetheless, the vote represents the consensus of the committee members’ deliberations and opinions, as well as their integration of the totality of the information into an overall benefit-risk calculus.

To assess the concordance of EMDAC votes and subsequent actions, all EMDAC meetings from 1 January 2009 through 31 December 2012 were reviewed. Only the meetings that involved the review of a specific drug were considered. The recommendations of the committee were then compared with the actual actions taken with respect to marketing or labeling. EMDAC recommendations were considered concordant with subsequent actions when a majority of the EMDAC members’ votes reflected the ultimate action.

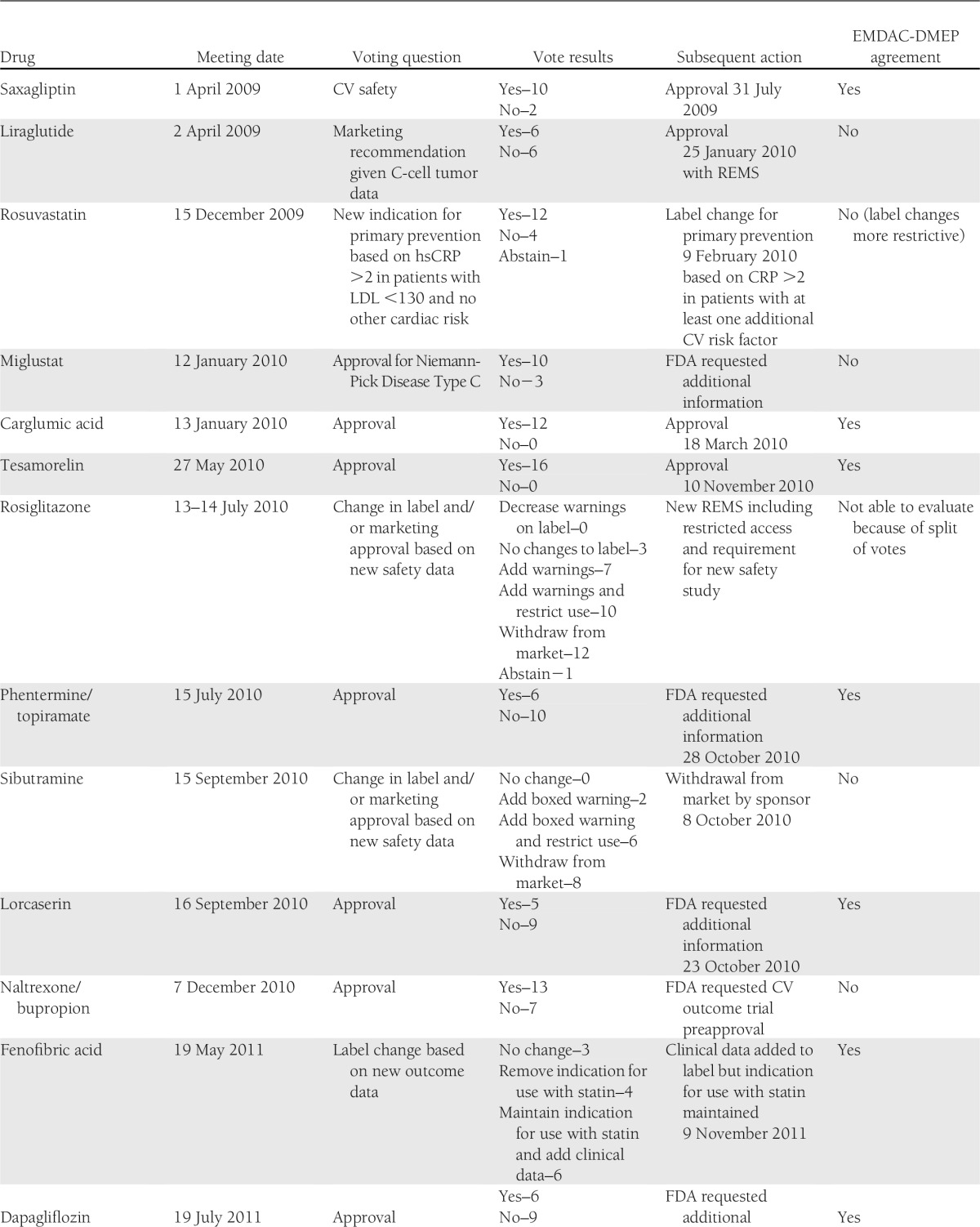

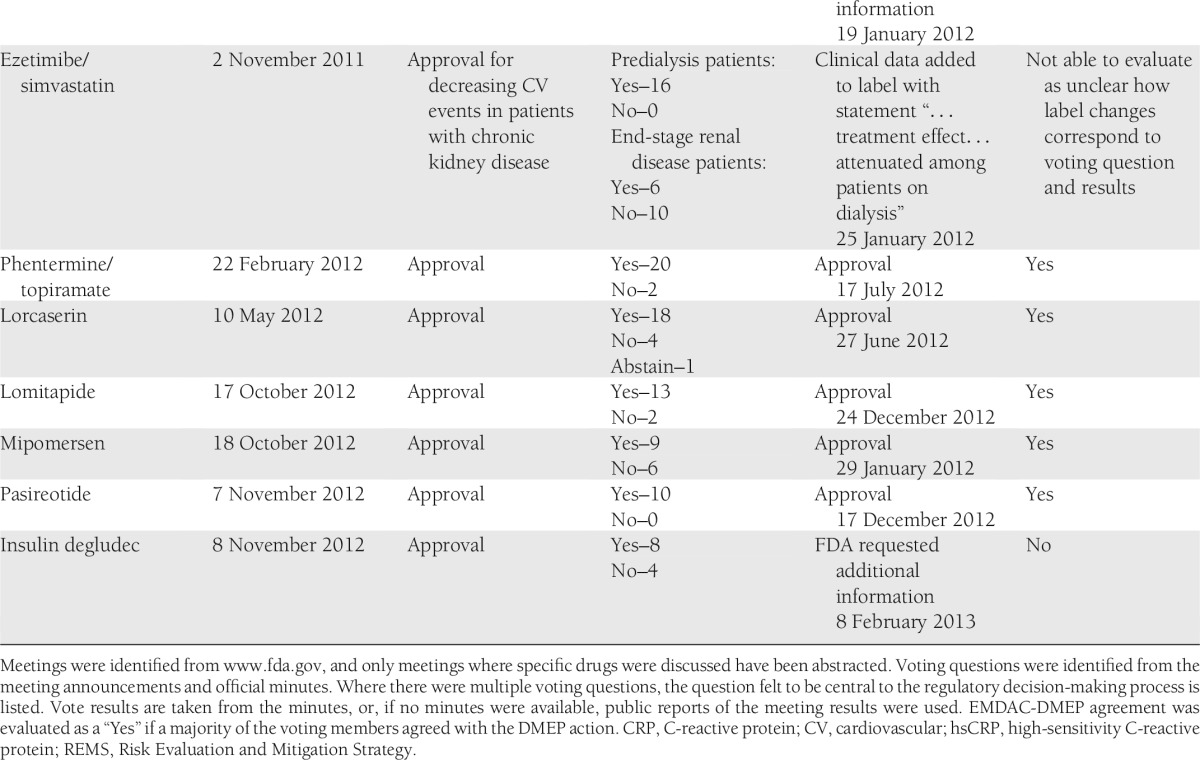

EMDAC met to discuss specific drugs 20 times during the period of interest (Table 1). In only 12 (60%) of these cases was the ultimate action concordant with the EMDAC vote. In two cases, concordance could not be assessed because of the complexity of the questions or actions considered. In two cases where lack of concordance was identified, a change in one vote would have resulted in a majority agreement with the action. In most cases of EMDAC-DMEP discordance, EMDAC members seemed to view the benefit-risk of the candidate more favorably. In the examples for miglustat, naltrexone/bupropion, and insulin degludec, clear majorities of EMDAC members favored approval while the FDA did not agree. In the case of sibutramine, a majority of EMDAC members did not support withdrawal from the market, but the drug was withdrawn soon after the meeting. In contrast, in the case of liraglutide, a majority of the EMDAC members did not support approval, but the drug was approved 9 months after the meeting.

Table 1.

Meetings of the EMDAC, 2009–2012

Importantly, lack of concordance between the EMDAC members and subsequent actions should not be interpreted as either EMDAC or FDA action being correct or incorrect. In fact, the action taken may be in full agreement with key points elicited during the committee’s discussions but not in the polling of the individual members. Alternatively, the FDA’s decision may have reflected considerations or data not available to the committee at the time of the vote. For example, if committee members indicated that certain additional information would change their votes, and this information is available to the FDA, the FDA’s action may be concordant with the committee’s recommendations but not their dichotomous vote. Rather, the relatively low degree of concordance should be viewed as reinforcing the challenges faced by the EMDAC. The discordance also raises the question as to whether EMDAC members are prepared to make a “yes” or “no” vote on issues as complex as benefit-risk assessment based on only a few hours of readings and deliberations. Discordance also suggests that the weighting of benefits and risks by committee members may differ from those of the DMEP and/or that they are being incompletely communicated during the meeting.

The challenges the EMDAC faces in its deliberations are also illustrated in meeting-to-meeting variability. During a 2-day meeting (28–29 March 2012), the EMDAC recommended that all new drugs for obesity should have data available from a cardiovascular outcomes trial prior to approval. Yet at the meetings immediately preceding (phentermine/topiramate on 22 February 2012) and following (lorcaserin on 10 May 2012) this meeting, the committee voted to approve drugs for obesity in the absence of these data. This may reflect the committee’s differential consideration of an abstract safety concern (the policy vote) when compared with a specific potential drug whose benefits are demonstrated in clinical trials.

It is likely that the estimated 60% concordance rate underestimates the challenges as several of the drugs considered (for example, carglumic acid and pasiroetide) appear to have been relatively uncontroversial, which made concordance likely. On the other hand, during votes where concordance was not achieved, the meeting transcripts reflect ambivalence among voting members on the benefit-risk proposition. For example, during the liraglutide meeting two members characterized their no votes as “wishy-washy” (9). These expressions of ambivalence may be considered by the DMEP as final FDA recommendations are formulated. However, the goal of enhancing public transparency is impaired to the degree that ambiguity remains or when regulatory actions are taken that are superficially in conflict with the committee votes.

The relatively high rate of discordance between EMDAC votes and subsequent actions suggest that the process should be re-evaluated and opportunities for optimization considered. For example, it has been suggested that advisory committees should not explicitly vote on questions regarding approvability (8). This would allow the meetings to focus on the key issues, permitting the FDA to receive the external perspectives and opinions it desires. Indeed, the absence of a vote might encourage committee members to more fully express the rationales for their views without the shortcut of the yes/no vote. While the vote may have value in the context of forcing a committee member to be explicit in their benefit-risk assessment, this will only have utility if the bases of the member’s integrative evaluation are explicitly understood and aligned with those used by the DMEP.

Another approach to increase the utility of the meetings and to enhance transparency would be to use more formal benefit-risk tools. These tools have the potential to make explicit the major drivers of a drug’s overall benefit and overall risk. Further, these tools also make apparent where differential assessments of benefits or risks exist between EMDAC members, DMEP staff, or the drug’s manufacturer (5,6). These tools might allow focused discussion on the specific points where divergent opinions exist—often the result of differing information sources. For example, it is anecdotally interesting to note that committee members directly involved with treating the disease for which the drug is intended often seem to weigh the benefits of the proposed new drug differently than those without direct experience with the patient population. In the case of liraglutide, the endocrinologists, consumer representative, and patient representative on the committee voted 6 yes and 2 no, while the nonendocrinologists voted 0 yes, 4 no, and 1 abstention (9).

EMDAC meetings play an important role in determining what therapies are available to practicing physicians. The relatively low level of concordance between EMDAC votes and subsequent actions emphasizes the challenges faced by the committee members. The “right” answer may not be clear even when large amounts of data are available and reviewed. It is critical that the EMDAC and the DMEP effectively communicate to each other and the public not only their overall benefit-risk assessments but the major contributors to the integrative assessment so that the differences in the valuation of attributes can be understood.

Acknowledgments

E.P.B. is a consultant to the pharmaceutical industry on problems of drug development, including preparation for advisory committee meetings. He has served as a consultant to Novo Nordisk, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Orexigen Pharmaceuticals, and Genzyme, whose drugs are discussed in this article, as well as for other companies. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Footnotes

See accompanying articles, PP. 1804, 2098, 2118, and 2126

References

- 1.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Advisory Committees: Laws, Regulation & Guidance [online], 2012. Available from http://www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/AboutAdvisoryCommittees/LawsRegulationsGuidance/default.htm Accessed 13 March 2013

- 2.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Advisory Committees: Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee [online], 2013. Available from http://www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/EndocrinologicandMetabolicDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/default.htm Accessed 13 March 2013

- 3.Mussen F, Salek S, Walker S. A quantitative approach to benefit-risk assessment of medicines - part 1: the development of a new model using multi-criteria decision analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16(Suppl. 1):S2–S15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levitan BS, Andrews EB, Gilsenan A, et al. Application of the BRAT framework to case studies: observations and insights. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;89:217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coplan PM, Noel RA, Levitan BS, Ferguson J, Mussen F. Development of a framework for enhancing the transparency, reproducibility and communication of the benefit-risk balance of medicines. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;89:312–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brass EP, Lofstedt R, Renn O. Improving the decision-making process for nonprescription drugs: a framework for benefit-risk assessment. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;90:791–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brass EP, Lofstedt R, Renn O. A decision-analysis tool for benefit-risk assessment of nonprescription drugs. J Clin Pharmacol 2013;53:475–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brass EP, Hiatt WR. Improving the FDA’s advisory committee process. J Clin Pharmacol 2012;52:1277–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting (official transcript), Silver Spring, Maryland, April 2, 2009 [online], 2009. Available from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/EndocrinologicandMetabolicDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM151176.pdf Accessed 17 April 2013