Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Type 2 diabetes is a risk factor for other forms of stroke, but its association with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) from ruptured saccular intracranial aneurysm (sIA) has remained unclear.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Kuopio Intracranial Aneurysm Database (www.uef.fi/ns) includes all ruptured and unruptured sIA cases from a defined catchment population in eastern Finland since 1980. We compared the age-adjusted incidences of type 2 diabetes in 1,058 ruptured and 484 unruptured sIA patients during 1994–2008, using the national registry of prescribed medicine purchases.

RESULTS

Of the 1,058 ruptured sIA patients, 43% were males and 57% females, with a median age at rupture of 51 and 56 years, respectively. From 1994 to 2008 or until death, 9% had been prescribed antidiabetes medication (ADM) with a median starting age of 58 years for males and 66 years for females. Of the 484 unruptured sIA patients, 44% were males and 56% females, with a median age at the diagnosis of 53 and 55 years, respectively, and 9% had used ADM, with a median starting age of 61 years for males and 66 years for females. The incidence of type 2 diabetes was highest in the age-group 60–70 years, with no significant differences between the ruptured and unruptured sIA patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study suggests that type 2 diabetes does not increase the risk of rupture of sIA, which is by far the most frequent cause of nontraumatic SAH.

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a devastating form of stroke that affects primarily the working-age population (1). In ~95% of cases, SAH is caused by the rupture of a saccular intracranial aneurysm (sIA) at the fork of intracranial extracerebral arteries in contrast to their infrequent fusiform, mycotic, and traumatic aneurysms. Some 2% of the general population develops sIAs (2–3) during life, but most do not rupture, as the general annual incidence of SAH is 4–7 per 100,000 (4–5). The sIA disease is a complex trait, affected by genomic (6–8) and acquired risk factors (3), the mechanisms of which in the formation, progress, and rupture of sIA pouches are poorly understood. Risk factors include age, female sex, smoking, hypertension, and excess drinking (3), and at least 10% of ruptured sIA patients have a family history (9–12). In a genome-wide association study, susceptibility loci at 2q33.1, 8q11.23, and 9p21.3 have been identified in Finnish subjects (7).

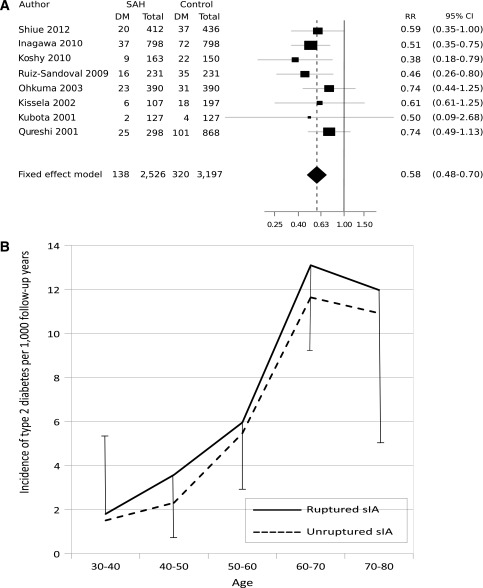

Type 2 diabetes is a complex trait affecting the arterial wall through several different mechanisms (13–16). Type 2 diabetes is a well-established risk factor for brain infarction and may predispose to intracerebral hemorrhage (17–19). Instead, the association between type 2 diabetes and sIA disease has remained unclear. Three recent studies (20–22) and our present review of the literature suggest that diabetes is a protecting factor for rupture of sIA (Table 1; Fig. 1A) (23–29). Both type 2 diabetes and sIA disease are associated with the 9p21.3 locus (6–8,30,31), although not with the same LD block, but they do not seem to share other loci in genome-wide association studies.

Table 1.

Previous studies on the association of diabetes and intracranial aneurysm disease* since 2001

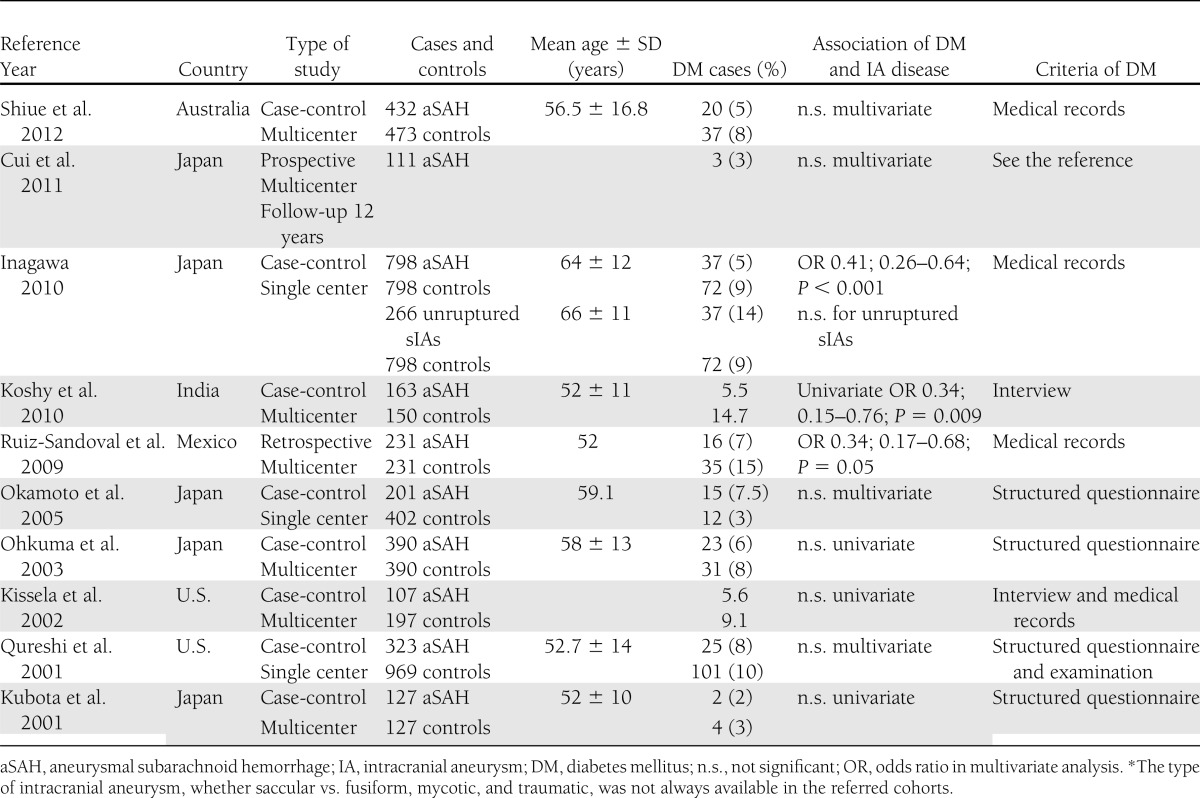

Figure 1.

A: Review of the literature of the association of diabetes and SAH in case-control studies published 2001–2012. The horizontal lines represent the 95% CIs of the OR or risk ratios (RRs). The size of the black box indicates the relative effect on the final fixed-effect estimate. The x-axis is logarithmic. B: Incidence of type 2 diabetes in 1,058 ruptured (aneurysmal SAH) and 484 unruptured sIA patients by age-group and 95% CIs.

Kuopio Intracranial Aneurysm Database (www.uef.fi/ns) contains all cases of unruptured and ruptured sIAs admitted to the Kuopio University Hospital (KUH) from a defined eastern Finnish catchment population since 1980 (11,12). We have studied the phenotype (11), familial form (2,9), risk factors (32), outcome (12,33), concomitant diseases (12), and genomics of sporadic and familial sIA disease (6–8,34). Here, we investigated retrospectively whether type 2 diabetes predisposes to sIA rupture by comparing 1,058 ruptured sIA patients with 484 unruptured sIA patients with first diagnosis between 1995 and 2007. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that arterial long-term effects of type 2 diabetes predispose to the rupture of the sIA wall rather than the formation of the sIA pouch. We also performed a review of the literature of the published cohorts to summarize the previous data on the association of type 2 diabetes and sIA disease.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Catchment population of KUH

During the study period from 1995 to 2007, Neurosurgery of KUH had solely provided full-time acute and elective neurosurgical services for the KUH catchment population in eastern Finland. The KUH area contains four central hospitals with neurologic units of their own. From 1995 to 2007, the geographic area remained the same but the population decreased from 880,914 to 851,066. The median age increased from 38 to 42 years in males and from 41 to 45 years in females, and the proportion of males remained unchanged at 49% (11).

Kuopio Intracranial Aneurysm Database

All cases of SAH diagnosed by spinal tap or computed tomography in the KUH catchment area have been acutely admitted to KUH for angiography and treatment if not moribund or very aged. Cases with unruptured intracranial aneurysm(s) but no SAH have also had neurosurgical consultation for elective occlusion. They were detected mostly as incidental findings in neuroimaging for other causes, less often as symptomatic, or by screening sIA family members. The findings were confirmed by four-vessel catheter angiography, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), or computed tomography angiography (CTA). The exact numbers of rejected cases are not available. KUH Neurosurgery maintains a database on all cases of unruptured and ruptured intracranial aneurysms admitted to the KUH since 1980. The database has been prospective since 1990, and earlier cases have been entered from hospital records. The database is run by a dedicated full-time nurse, who interviews all new case subjects, and collects and codes variables with detailed information, including the family history. The criterion for an sIA family is at least two affected first-degree relatives (11). Clinical data from the hospital periods and follow-up visits are entered. The use of prescribed medications (1995–2008) before and after the sIA diagnosis, occurrence of cancer and other diagnosed diseases, and causes of death have been entered from national registries. The phenotype, genomics, and outcome of eastern Finnish sIA disease have been analyzed in several studies (2,6–9,11,12,33,34).

Study population

The inclusion criteria were citizenship of Finland and residence in the KUH catchment area at first diagnosis of sIA disease between 1 January 1995 and 31 December 2007; admission alive to KUH, and verification of sIA(s) by angiography or at autopsy. The exclusion criteria were rupture of an intracranial aneurysm other than a saccular one (e.g., fusiform, traumatic, mycotic) or any other vascular malformation.

Antidiabetes or antihypertension medication

The diagnosis for type 2 diabetes was made based on the database of purchased antidiabetes drugs. The Social Insurance Institution of Finland maintains a nationwide registry of all prescribed drugs purchased from the pharmacies since 1994. Information on purchases of all prescribed drugs by the 1,542 sIA patients between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 2008 was obtained from the Social Insurance institute of Finland and linked to Kuopio Intracranial Aneurysm Database. The recruitment period, from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2007, allows data on purchased drugs for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the diagnosis of sIA. Antidiabetes (ADM) and antihypertension medications were classified according to the anatomic therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification system. The patients with type 1 diabetes, first identified according to their insulin use and by their special reimbursement code and finally verified from the case reports, were excluded from the analysis.

Variables

The variables used in the analyses were as follows for all sIA patients: 1) sIA disease carrier (sex, age at first sIA diagnosis or at rupture of sIA, sporadic vs. familial sIA patient, use and starting age of antihypertensive medication, and use and starting age of ADMs) and 2) sIA disease (location and diameter of the primary sIA and one versus two or more sIAs.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Multivariate analyses were performed using the binomial logistic regression model. To account for difference of age at the diagnosis of sIA disease between the unruptured and ruptured groups, we standardized the age to the joint age distribution of both age-groups. Standardized rates and CIs were calculated according to the methodology of Fay and Feuer (35), as the occurrences of diabetes are low in different age-groups. The incidences of ADM in the ruptured and unruptured patients were calculated for 10-year age intervals, and the CIs in each age group were calculated as exact central Poisson CIs (36).

Review of the literature

A PubMed search for articles on SAH risk and diabetes was made from 2001 to April 2012 with the following keyword(s): subarachnoid hemorrhage, stroke, diabetes, and case-control. Bibliographies of the retrieved articles were examined for further relevant publications. Cross-checking was continued until no further publications in English were found. Only the studies that reported the number of patients exposed to diabetes, allowing recalculation of the associated SAH risk, were included. Studies restricted to subgroup of patients (e.g., young patients) were excluded. When there were multiple studies from the same cohort, the newest published study was included. A fixed-effects Mantel-Haenszel method was used in the review of the literature to estimate pooled odds ratios (ORs) and CIs. The appropriateness of fixed-effects model was evaluated by the Cochran Q test, which indicated no heterogeneity of study effects (Q = 3; df = 7; P = 0.7).

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the KUH. Data fusion from the national registries was performed with the approval from Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland.

RESULTS

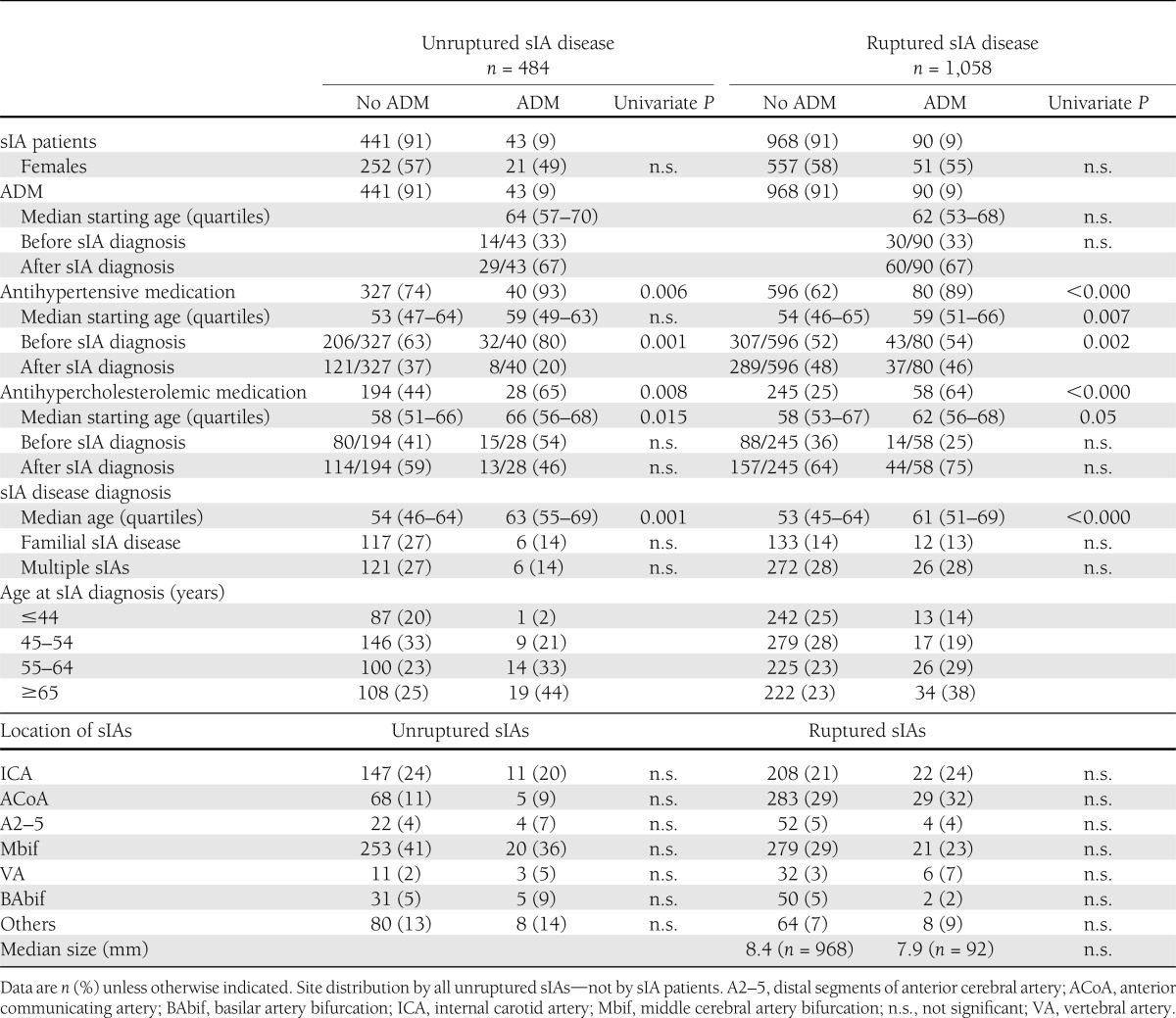

Unruptured sIA disease

Of the 1,542 sIA patients, 484 (31%) carried an unruptured sIA disease (Table 2). There were 211 (44%) males and 273 (56%) females, and their median ages at the first diagnosis were 53 and 55 years, respectively. The most frequent sIA location was the middle cerebral artery bifurcation (48%). Two or more sIAs were diagnosed in 127 (26%) patients. Familial sIA disease was found in 123 (25%) patients. Of the 484 patients, 224 underwent microsurgical and 56 endovascular occlusion therapy of sIA(s).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics and ADM of 1,542 sIA patients admitted to KUH 1995–2007

ADM in unruptured sIA patients

During the observation period for drug use—from 1994 to 2008 or death—43 (9%) of the 484 unruptured sIA patients used ADM. The median starting age was 61 years for the 22 males and 66 years for the 21 females. The ADM had been started before the sIA diagnosis in 14 (31%) cases and after the diagnosis in 31 (69%) cases. In multivariate analysis, only the age at diagnosis (OR 1.03 [95% CI 1.012–1.051, P = 0.01) independently associated with ADM.

Ruptured sIA disease

There were 1,058 ruptured sIA patients, 451 (43%) of whom were male and 607 (57%) female, with median ages at first rupture of sIA of 51.0 and 56.0 years, respectively (Table 2). The most frequent location of ruptured sIA was the anterior communicating artery at 29%. Two or more sIAs were diagnosed in 298 (28%) patients. Familial sIA disease was carried by 145 (14%) patients.

ADM in ruptured sIA patients

From 1994 to 2008 or death, 90 (9%) of the 1,058 ruptured sIA patients used ADM. The median starting age was 58 years for the 40 (44%) males and 66 years for the 50 (56%) females. The ADM had been started before the rupture in 30 (33%) cases and after the rupture in 60 (67%) cases. In multivariate analysis, the age at rupture (OR 1.05) associated independently with ADM. The cumulative mortality rate at 12 months after the rupture of sIA was 25%.

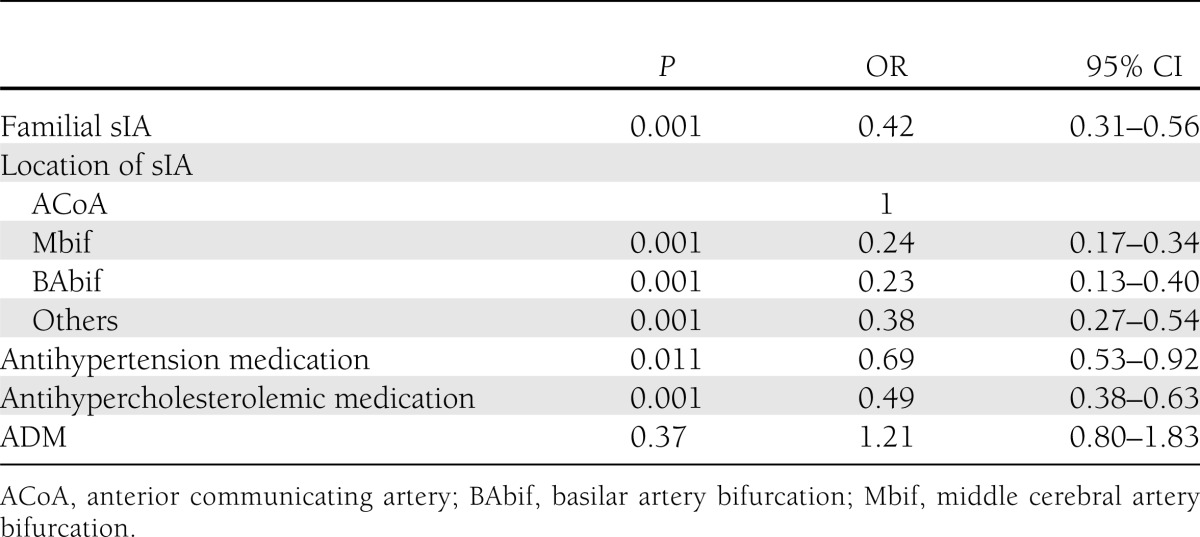

In multivariate analysis of all 1,542 sIA patients, familial sIA (OR 0.42), sIA in middle cerebral artery bifurcation (0.24), sIA in basilar artery bifurcation (0.23), sIA in “other” location (0.38), antihypercholesterolemic medication (0.49), and antihypertension medication (0.57) independently associated with rupture of sIA, while ADM did not (Table 3).

Table 3.

Independent risk factors for sIA rupture in the study cohort of 1,542 sIA patients in multivariate binomial regression analysis

ADMs used

Between 1994 and 2008, the 133 patients with ADM used 22 different drugs according to the anatomic therapeutic chemical classification. During the study interval, the most frequently used ADMs were as follows: metformin and other oral ADM (n = 96), insulin combined with oral ADM (n = 29), and monotherapy with insulin (n = 7).

Incidence of type 2 diabetes

The age-standardized incidence of type 2 diabetes was 6.36 (4.60–8.63) per 1,000 follow-up years for patients with unruptured sIA and 6.98 (95% CI 5.62–8.59) per 1,000 follow-up years for patients with ruptured sIA. The incidence of type 2 diabetes was highest in the group of 60–70 years, with no significant differences between the ruptured and unruptured patients (Fig. 1B).

CONCLUSIONS

We tested the hypothesis that type 2 diabetes would increase the risk of sIA rupture by comparing 1,058 ruptured sIA patients and 484 unruptured sIA patients first diagnosed between 1995 and 2007 in a defined eastern Finnish population. The type 2 diabetic patients were identified by ADM usage between 1994 and 2008, obtained from the Finnish registry of prescribed drug purchases. The ADM usage, 9% in both cohorts, did not associate with the rupture of sIA in multivariate analysis.

Type 2 diabetes is a well-established risk factor for brain infarction and may predispose to intracerebral hemorrhage (17–19). Instead, the association between type 2 diabetes and sIA disease has remained unclear. Unlike our study and the cohort of 329 cases of SAH from sIA published in 1984 (37), three recent studies (20–22) and our present review of the literature from the six published ones suggested that diabetes is a protective factor for SAH (Table 1; Fig. 1). Inagawa hypothesized that the protecting effect of diabetes would be connected to enhanced atherosclerosis in the sIA wall, making it less prone to rupture (21). Atherosclerosis has not been identified as an independent risk factor for saccular aneurysms that form in the branching sites of intracranial extracerebral arteries (3)—unlike in fusiform aneurysms, e.g., in the aorta (38,21). In theory, a genetic link that predisposes to the development of type 2 diabetes and lowers the risk of developing sIAs may exist. Hypercholesterolemia was associated with reduced risk of SAH in three case-control studies (40% risk reduction), with no clear sex difference (3). Another theoretical protective factor in diabetic patients might be more efficient diagnosis and treatment of hypertension—an independent risk factor of the sIA disease (3).

In the present cohort, the median ages for diagnosis of the sIA disease were 54 years for the unruptured cases and 54 years for the ruptured sIA cases. Instead, the median starting age for ADM was 63 and 62 years, respectively. Consequently, the impact of diabetes on arterial walls may manifest so late that it does not show in the sIA disease.

Type 2 diabetes and sIA disease are complex traits with genomic components. The 9p21.3 locus associates with both diseases (6,7,30,31) but not in the same linkage disequilibrium block. To our knowledge, other shared susceptibility loci have not been found, suggesting that type 2 diabetes and sIA disease do not share genomic predisposition.

Unfortunately, the sIA registry does not contain reliable data on BMI, smoking, or drinking habits of the sIA patients. An obvious weakness was also the lack of data on the diagnostic tests used for type 2 diabetes such as fasting glucose levels and oral glucose tolerance tests. On the other hand, we compared the ruptured sIA patients with the unruptured sIA patients, and both had their blood glucose levels studied during the hospitalization for the sIA disease. In ruptured sIA patients, these glucose levels are unreliable because of impact of ruptured sIA and its neurointensive care. Of the 133 ADM users, as many as 81 had started ADM within 12 months after the sIA diagnosis. Still, we may have missed cases of unmedicated diabetes during the period of ADM purchases, and the vascular effects of diabetes may be different in medicated and untreated individuals. In a cross-sectional population-based survey in Finland between October 2004 and January 2005, the total prevalence of both previously diagnosed and screen-detected type 2 diabetes was 16% in men and 11% in women aged 45–74 years (39). Previous studies registered the diabetes status only once, missing diabetes cases presenting after the sIA diagnosis. The strengths of the current study derive from the Finnish health care system. Finland is divided into mutually exclusive catchment areas among the five university hospitals. This system allows the creation of disease cohorts that are unselected and minimally biased. Very accurate population statistics and a stable population ensure that few patients are lost to follow-up.

In conclusion, type 2 diabetes is a risk factor for two forms of stroke, brain infarction and intracerebral hemorrhage (17–19), but our study suggests that type 2 diabetes does not increase the risk of rupture of sIA, which is by far the most frequent cause of nontraumatic SAH.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, North Savo Regional Fund, Aarne Koskelo Foundation, Kuopio University Hospital, and Finnish Academy of Sciences.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

A.E.L. collected and analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. M.I.K. analyzed data and edited the manuscript. A.Ri. collected data. T.K., A.Ro., J.R., J.H., J.G.E., J.E.J., and M.v.u.z.F collected data and edited the manuscript. A.E.L. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.van Gijn J, Kerr RS, Rinkel GJ. Subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet 2007;369:306–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ronkainen A, Miettinen H, Karkola K, et al. Risk of harboring an unruptured intracranial aneurysm. Stroke 1998;29:359–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feigin VL, Rinkel GJ, Lawes CM, et al. Risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage: an updated systematic review of epidemiological studies. Stroke 2005;36:2773–2780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Barker-Collo SL, Parag V. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:355–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Rooij NK, Linn FH, van der Plas JA, Algra A, Rinkel GJ. Incidence of subarachnoid haemorrhage: a systematic review with emphasis on region, age, gender and time trends. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007;78:1365–1372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Magnusson KP, et al. The same sequence variant on 9p21 associates with myocardial infarction, abdominal aortic aneurysm and intracranial aneurysm. Nat Genet 2008;40:217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bilguvar K, Yasuno K, Niemelä M, et al. Susceptibility loci for intracranial aneurysm in European and Japanese populations. Nat Genet 2008;40:1472–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasuno K, Bilguvar K, Bijlenga P, et al. Genome-wide association study of intracranial aneurysm identifies three new risk loci. Nat Genet 2010;42:420–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronkainen A, Hernesniemi J, Puranen M, et al. Familial intracranial aneurysms. Lancet 1997;349:380–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruigrok YM, Rinkel GJ, Wijmenga C. Familial intracranial aneurysms. Stroke 2004;35:e59–60 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Huttunen T, von und zu Fraunberg M, Frösen J, et al. Saccular intracranial aneurysm disease: distribution of site, size, and age suggests different etiologies for aneurysm formation and rupture in 316 familial and 1454 sporadic eastern Finnish patients. Neurosurgery 2010;66:631–638; discussion 638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huttunen T, von und Zu Fraunberg M, Koivisto T, et al. Long-term excess mortality of 244 familial and 1502 sporadic one-year survivors of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage compared with a matched Eastern Finnish catchment population. Neurosurgery 2011;68:20–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2011;34(Suppl. 1):S62–S69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyssenko V, Jonsson A, Almgren P, et al. Clinical risk factors, DNA variants, and the development of type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2220–2232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindström J, Tuomilehto J. The diabetes risk score: a practical tool to predict type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes Care 2003;26:725–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nolan CJ, Damm P, Prentki M. Type 2 diabetes across generations: from pathophysiology to prevention and management. Lancet 2011;378:169–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Almdal T, Scharling H, Jensen JS, Vestergaard H. The independent effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus on ischemic heart disease, stroke, and death: a population-based study of 13,000 men and women with 20 years of follow-up. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1422–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, et al. INTERSTROKE investigators Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet 2010;376:112–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, et al. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 2010;375:2215–2222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruiz-Sandoval JL, Cantú C, Chiquete E, et al. RENAMEVASC Investigators Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in a Mexican multicenter registry of cerebrovascular disease: the RENAMEVASC study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;18:48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inagawa T. Risk factors for the formation and rupture of intracranial saccular aneurysms in Shimane, Japan. World Neurosurg. 2010;73:155-164 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Koshy L, Easwer HV, Premkumar S, et al. Risk factors for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in an Indian population. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;29:268–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui R, Iso H, Yamagishi K, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of stroke and its subtypes among Japanese: the Japan public health center study. Stroke 2011;42:2611–2614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohkuma H, Tabata H, Suzuki S, Islam MS. Risk factors for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in Aomori, Japan. Stroke 2003;34:96–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kissela BM, Sauerbeck L, Woo D, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage: a preventable disease with a heritable component. Stroke 2002;33:1321–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kubota M, Yamaura A, Ono J. Prevalence of risk factors for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: results of a Japanese multicentre case control study for stroke. Br J Neurosurg 2001;15:474–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qureshi AI, Suri MF, Yahia AM, et al. Risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 2001;49:607–612; discussion 612–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiue I, Arima H, Hankey GJ, Anderson CS, ACROSS Group Modifiable lifestyle behaviours account for most cases of subarachnoid haemorrhage: a population-based case-control study in Australasia. J Neurol Sci 2012;313:92–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okamoto K, Horisawa R, Ohno Y. The relationships of gender, cigarette smoking, and hypertension with the risk of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case-control study in Nagoya, Japan. Ann Epidemiol 2005;15:744–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V, et al. MAGIC investigators. GIANT Consortium Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet 2010;42:579–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott LJ, Mohlke KL, Bonnycastle LL, et al. A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science 2007;316:1341–1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindgren A, Huttunen T, Saavalainen T, et al. Increased incidence of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage on Sundays and Mondays in 1,862 patients from Eastern Finland. Neuroepidemiology 2011;37:203–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karamanakos PN, von Und Zu Fraunberg M, Bendel S, et al. Risk factors for three phases of 12-month mortality in 1657 patients from a defined population after acute aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg 2012;78:631–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yasuno K, Bakırcıoğlu M, Low SK, et al. Common variant near the endothelin receptor type A (EDNRA) gene is associated with intracranial aneurysm risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:19707–19712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fay MP, Feuer EJ. Confidence intervals for directly standardized rates: a method based on the gamma distribution. Stat Med 1997;16:791–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garwood F. Fiducial limits for the Poisson distribution. Biometrika 1936;28:437–442 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams HP, Jr, Putman SF, Kassell NF, Torner JC. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus among patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Arch Neurol 1984;41:1033–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornuz J, Sidoti Pinto C, Tevaearai H, Egger M. Risk factors for asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm: systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based screening studies. Eur J Public Health 2004;14:343–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peltonen M, Korpi-Hyövälti E, Oksa H, et al. Prevalence of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and other disturbances in glucose metabolism in Finland – The FIN-D2D survey. Finnish Medical Journal 2006;3:163–170(in Finnish with English summary) [Google Scholar]