Abstract

Aim of the study

Gastric cancer is characterized by varying secretion of mucus. Mucin producing gastric carcinoma (MUC) is thought to be a histological subtype with a worse prognosis. The aim of this study was to compare the clinicopathological differences between MUC and other types of gastric carcinoma without secretion of mucus (NMUC).

Material and methods

We reviewed two groups of patients with pathologically confirmed gastric cancer: 34 patients with MUC and 36 cases with NMUC. Patients’ sex, age, tumor location, stage of disease and type in the Lauren classification were examined. We analyzed the presence of lymph node metastasis, peritoneal dissemination and liver metastasis. Additionally, treatment response, toxicity and survival rates were evaluated.

Results

We observed a statistically significant relationship between MUC subtype and patients’ sex: MUC was found mostly in women (p = 0.017). There were no significant differences between the two gastric cancer groups according to age, tumor location, size of tumor or stage of disease. In the NMUC group the rate of liver metastasis was significantly higher (p = 0.001). The overall survival rate and progression-free survival for MUC patients were lower than those for NMUC patients. There was no significant difference in survival rates between the two groups. In analysis of logistic regression we distinguished significantly advantageous (number of chemotherapy cycles) and disadvantageous parameters (advanced stage in TNM), which influenced the chemotherapy effect.

Conclusions

The MUC type itself is not an unequivocally negative prognostic agent. Poor prognosis was correlated with more advanced stages at diagnosis, particularly with dissemination of cancer.

Keywords: gastric cancer, immunohistochemistry, MUC, NMUC, prognosis

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fourth neoplastic cause of death in Europe [1]. The prognosis and therapy depend on the stage of histology differentiation and clinical stage of disease [2]. The observations of gastric cancer biology led to the development of various classifications of gastric cancer. The most frequently used classifications are Bormann's classification, which considers cancer gross morphology [3], and classifications based on results of histopathological analysis such as the Lauren [4], Goseki [5] and WHO classifications [6]. Mucus secretion by cancer cells is described by the Goseki classification [5]. Mucins are high molecular weight glycoproteins produced by gastric epithelial cells. Various alterations in the type of secreted glycoproteins (mucins) may have an impact on cell growth regulation, immune response and cell adhesion. These changes may affect the tumor ability of invasion and metastasis. Gastric cancer shows a wide variation in the level of secreted mucins compared with healthy tissue. Individual types of gastric cancer differ from each other in mucus secretion. The cells of ring-cell carcinoma are characterized by mucin production, and other histological types of cancer show varying secretion. Mucinous adenocarcinoma of the stomach (MUC) is a rare histological type found in 2.4-4.9% of gastric cancer cases [7]. Routine rapid estimation of mucus secretion on the basis of the mucicarmine staining together with stage of histological differentiation may have prognostic value with respect to treatment response, as well as the presence and localization of metastases [8].

The aim of this study is to analyze the differences between a group of patients with mucin secreting gastric cancer (MUC) and a group without extracellular mucin (non-MUC). We evaluated demographic features of patients, survival time, macro and microscopic features of tumor, and response to treatment. We also examined the correlation between mucin secretion and well-known predictors such as TNM classification and histological subtype of gastric cancer as well as survival rates (OS).

Material and methods

We analyzed 70 patients with histopathologically confirmed gastric cancer (41 men and 29 women), who were treated in the Clinical and Experimental Oncology Department, Cancer Center and Institute of Oncology in Gliwice, during 2004-2010. The characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological and demographic findings of mucin producing gastric cancer (MUC) and gastric cancer without mucin secretion (NMUC)

| Demographic features | MUC n = 34 | NMUC n = 36 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| female | 19 (55.9%) | 10 (27.8%) | |

| male | 15 (44.1%) | 26 (72.2%) | 0.017 |

| Age | 55.3 ±10.7 | 57.1 ±11.7 | 0.5018 |

| 20-70 | 29-80 | ||

| Age range groups | |||

| 20-40 years | 3 (8.8%) | 5 (13.9%) | |

| 40-60 years | 17 (50%) | 17 (47.2%) | |

| > 60 years | 14 (41.2%) | 14 (38.9%) | 0.8012 |

| Clinicopathological findings | |||

| Location | |||

| Corpus of the stomach | 15 (44%) | 15 (42%) | |

| Cardia | 7 (20%) | 7 (19%) | |

| Pylorus | 6 (18%) | 9 (25%) | |

| Multifocal location | 6 (18%) | 5 (14%) | 0.5699 |

| TNM classification | |||

| II | 10 (29%) | 6 (18%) | |

| III | 9 (27%) | 6 (18%) | |

| IV | 15 (44%) | 24 (64%) | 0.1634 |

| Lauren classification | |||

| Intestinal type | 19 (56%) | 22 (61%) | |

| Diffuse type | 14 (41%) | 12 (33%) | |

| Unclassified (mixed) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 0.7225 |

| Surgical procedures | |||

| Radical operation | 15 (44%) | 14 (39%) | |

| Palliative operation | 4 (12%) | 8 (22%) | |

| Inoperable | 15 (44%) | 14 (39%) | 0.5101 |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| DCF | 8 (22%) | 14 (40%) | |

| 5 FU-monochemotherapy | 15 (44%) | 8 (23%) | 0.137 |

| Radiotherapy | |||

| Yes | 21 (66%) | 11 (34%) | 0.008 |

| No | 13 (34%) | 25 (66%) | |

On the basis of mucus selective staining examination of oligobiopsy samples, all patients were divided into two groups: 34 (48.6%) patients with mucin secreting cancer (MUC) and 36 (51.4%) patients without evident secretion of mucins in mucicarmine staining (NMUC). Tumor stage was established on the basis of imaging examination, the presence of lymph node metastasis, peritoneal dissemination, liver metastasis and physical examination.

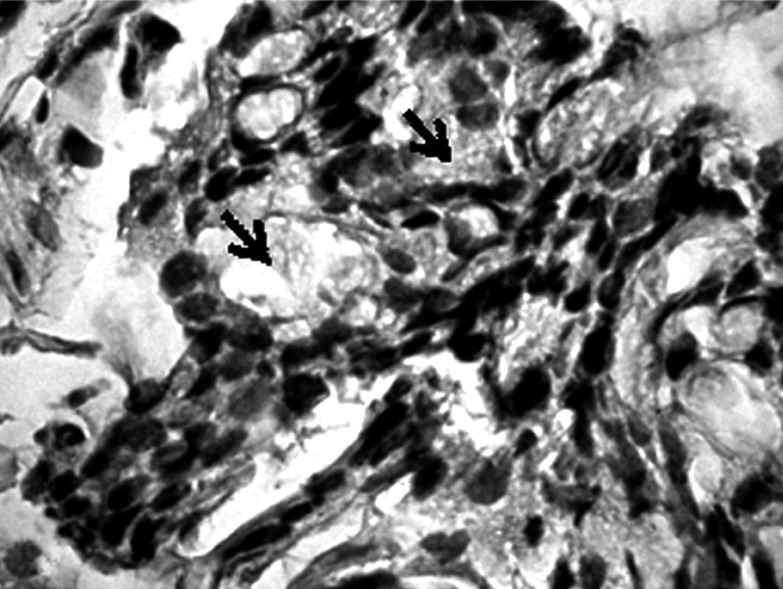

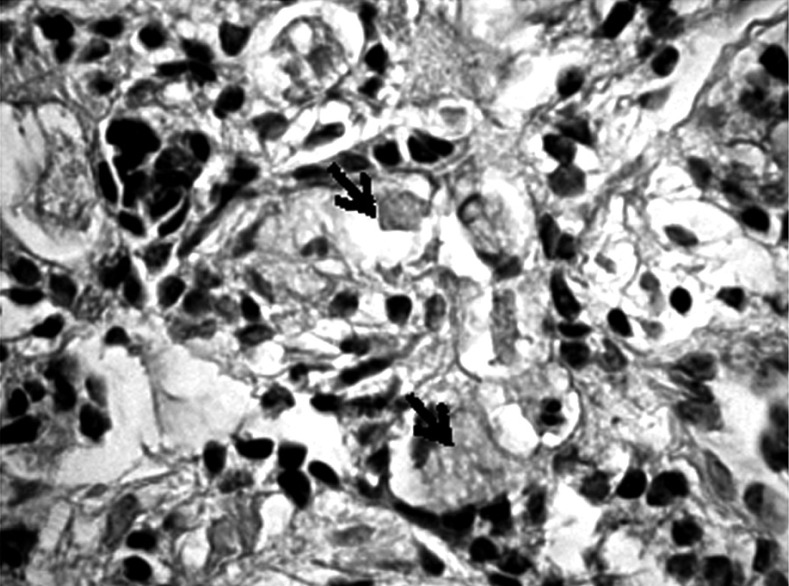

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissues were cut into 4 µm sections, then deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated. Metaplasia was confirmed using combined alcian blue/periodic acid-Schiff stains (B/PAS). It was considered to exist if at least 5% of neoplastic cells were stained. The degree of positive staining was graded as follows: (+) from 5% to 50% and (++ ) > 50% of the neoplastic cells stained (Figs. 1-6).

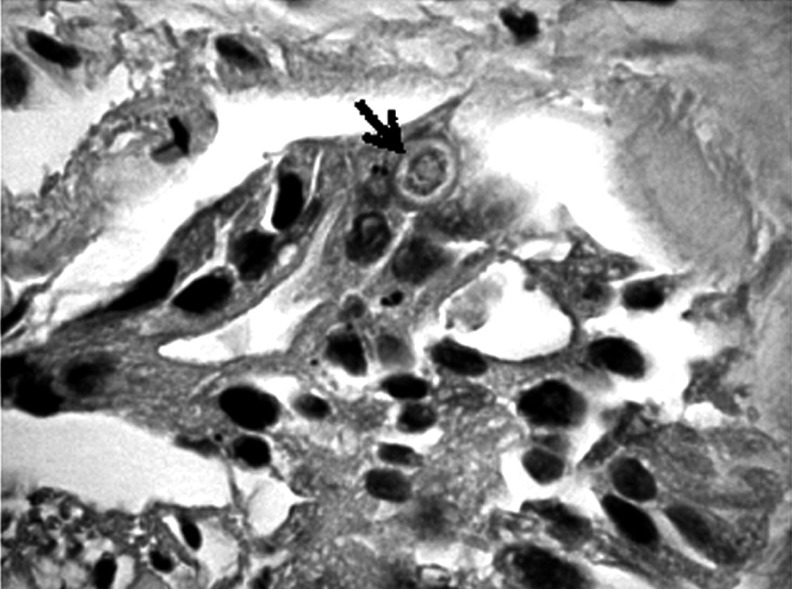

Fig. 1.

Positive staining on the presence of mucopolysaccharides in a few cells of gastric cancer (→). Mucicarmine staining magnification 300×

Fig. 6.

Strongly positive staining – signet ring cancer cells. Mucicarmine staining, magnification (→) 300×

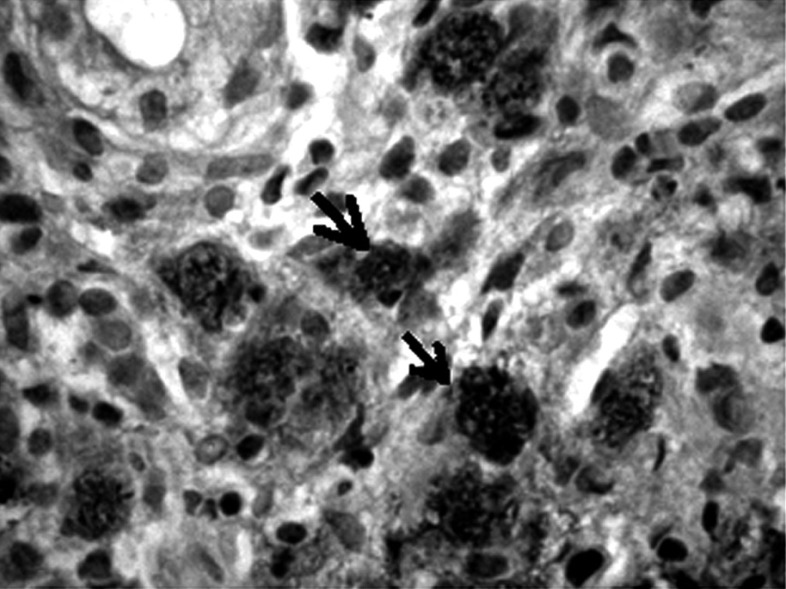

Fig. 2.

Positive staining on the presence of mucopolysaccharides in a single cell of gastric cancer (→). Mucicarmine staining, magnification 300×

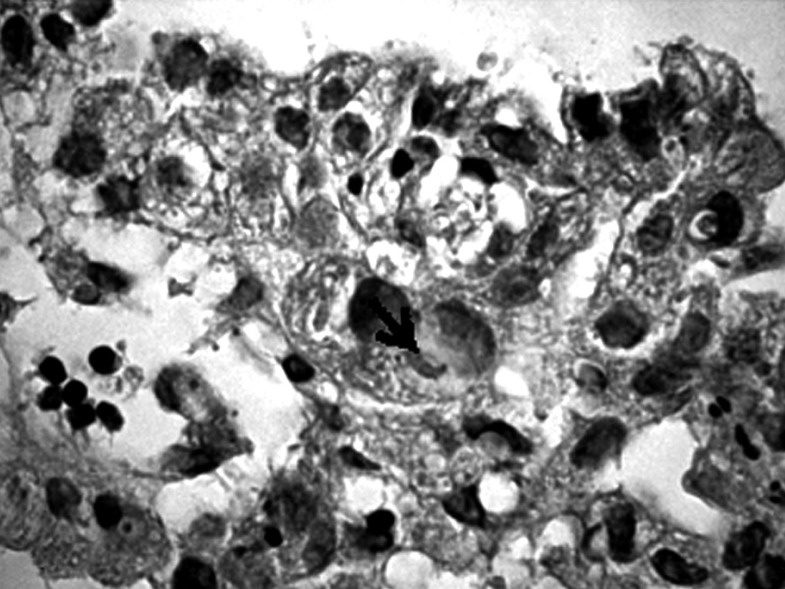

Fig. 3.

Negative staining in cancer cells. Mucicarmine staining, magnification 300×

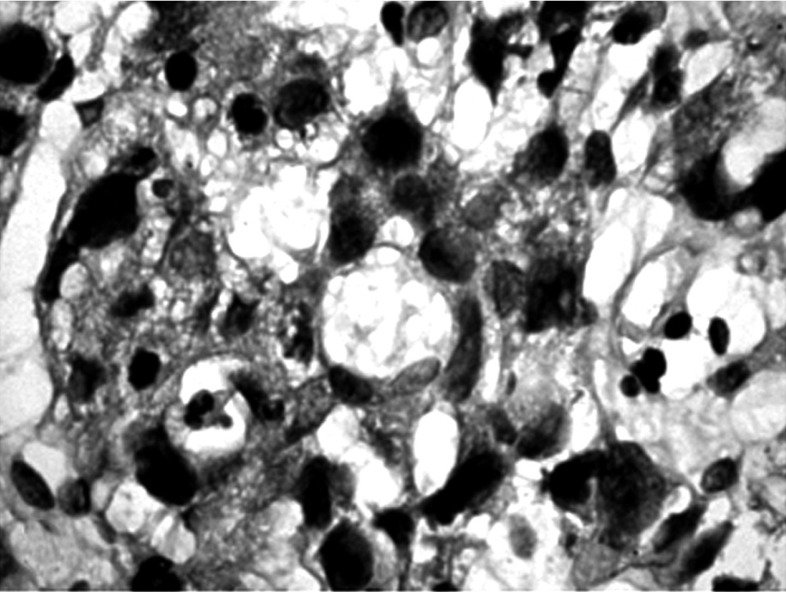

Fig. 4.

Positive staining in the presence of mucopolysaccharides in most cells of cancer and in stroma (→). Mucicarmine staining, magnification 300×

Fig. 5.

Positive staining in the presence of mucopolysaccharides in most cells of gastric cancer (→). Mucicarmine staining, magnification 300×

The two groups were compared in terms of selected clinicopathological features such as age, tumor stage and localization, and histology subtype in the Lauren classification. We also analyzed the presence of lymph node metastasis, peritoneal dissemination, liver metastasis and the relationship between MUC and treatment response.

Macroscopic classification was based on modified Borrmann's classification [3]. The tumors were histologically classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and Lauren classification. Tumor staging was assessed using the tumor node metastasis (TNM) system according to the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) [9]. The clinical status of the patients was estimated according to ZUBROD classification. The treatment response was qualified according to the WHO classification. Clinical toxicity was recorded on the basis of CTCAE (version 4.0).

Statistical analysis was carried out using STATISTICA 7 software. The qualitative variables are presented as the percentage of their occurrence in both groups and evaluated with χ2 with applicable Yates correction. Differences were considered as statistically significant if the p value was ≤ 0.05. MUC and NMUC patients survival was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences in survival were analyzed by the log-rank test. The calculations for multiple logistic regression were conducted in WinBUGS v.1.4.3 using the Monte Carlo method.

Results

Depending on the tumor stage, patients underwent gastrectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy or preoperative chemoradiotherapy with sequent surgical treatment. Two groups of tumor types were observed: 34 with diagnosis of MUC and 36 patients without mucin production. The complete characteristics of patients with regard to demographic and clinicopathological features are presented in Table 1.

In the present analysis, there was a significant difference in sex between patients with MUC and NMUC (p = 0.017). The presence of MUC was more often observed in women (55.9%). In both groups gastric carcinoma was more frequently diagnosed in the age range from 40 to 60 years (MUC: 50%; NMUC: 47.2%). The mean age for MUC and NMUC patients was similar (55.3 ±10.7 for MUC and 57 ±11.7 for NMUC). Considering the primary tumor localization we estimated that NMUC occurred most often in pylorus of the stomach (25%). MUCs were similarly localized in the above-mentioned part of the stomach with frequency 18% and additionally in multifocal location (18%). With reference to Lauren histological classification, we observed more frequent occurrence of diffuse type in MUC (41% of the examined group). As opposed to MUC, intestinal type was found more frequently in NMUC carcinomas (61% of the studied group). There was no statistically significant difference in Lauren classification types between patients with MUC and NMUC.

In the group of patients with MUC, metastases to lymph nodes, liver and peritoneal dissemination were observed in 65%, 6% and 29% patients respectively, and in the NMUC group in 67%, 28% and 39% patients respectively. In the present analysis, a significant relationship between NMUC type and presence of liver metastases was found (p = 0.001) (Table 2). No significant differences were seen between the MUC and NMUC groups in lymph node metastases and peritoneal dissemination. Both MUC and NMUC cancers more often occurred in stage IV according to the TNM classification, 44% in MUC and 67% in NMUC patients.

Table 2.

The presence of metastases in patients with mucin producing gastric cancer (MUC) and gastric cancer without mucin secretion (NMUC)

| Metastasis | MUC n = 34 (%) | NMUC n = 36 (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| Present | 22 (65) | 24 (67) | |

| Absent | 12 (35) | 12 (33) | 0.8629 |

| Peritoneal dissemination | |||

| Present | 10 (29) | 10 (28) | |

| Absent | 24 (71) | 26 (72) | 0.8797 |

| Liver metastasis | |||

| Present | 2 (6) | 14 (39) | |

| Absent | 32 (94) | 22 (61) | 0.0010 |

Chemotherapy was given to 45 patients; 51% of them received polychemotherapy (DCF) and 49% monochemotherapy (5-FU). Patients with MUC better tolerated systemic therapy: side effects occurred in 70% of patients, while side effects were observed in 74% of NMUC patients. In both groups severe side effects in grade 3-4, according to WHO, were observed with the same frequency (9%). Complete estimation of toxicity observed during chemotherapy is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Side effects during chemotherapy

| Side effects | MUC n = 34 (%) | NMUC n = 36 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Anemia | 3 (4) | 3 (4.3) |

| Neutropenia | 4 (6) | 4 (5.7) |

| Diarrhea | 3 (4) | 3 (4.3) |

| Nausea and vomiting | 6 (9) | 7 (10) |

| Bleeding from digestive tract | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.4) |

| Epilation | 0 | 5 (7.1) |

| Others | 1 (1.5) | 4 (5.7) |

| Without side effects | 21 (30) | 18 (25.7) |

| Overall toxicity WHO grade 3-4 | 6 (9) | 6 (8.6) |

Treatment response (CR + PR) was the same in both groups (11% NMUC; 11% MUC). Disease dissemination was observed faster (up to 6 months) and more often in patients with NMUC (progression occurred in 22% of patients with NMUC and in 13% with MUC type).

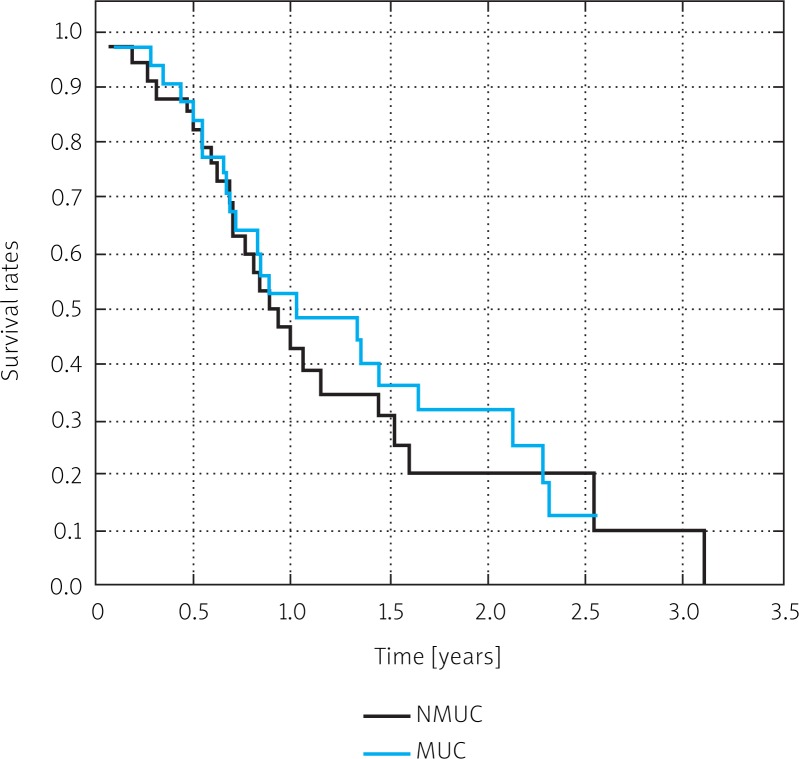

The overall survival in both groups was similar. The 2-year survival rate was 31% in MUC patients and 20% in NMUC patients (Fig. 7). There was no significant difference in survival rates (p = 0.322).

Fig. 7.

Survival curves for patients with mucinous adenocarcinoma (MUC) and non-mucinous adenocarcinoma (NMUC). P < 0.05

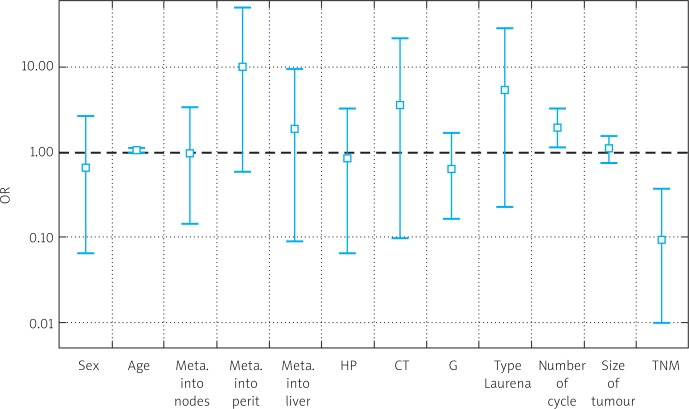

Logistic regression analysis revealed parameters that had significantly advantageous and disadvantageous effects on chemotherapy. It showed that primarily more advanced stage according to TNM classification had a negative impact on chemotherapy response (p = 0.001), and that peritoneal dissemination was not significant (p = 0.06). It also showed that the number of treatment cycles was considered a significantly disadvantageous factor (p = 0.006). Results of logistic regression are shown in Table 4 and Fig. 8.

Table 4.

Parameters significantly influencing chemotherapy effect

| Risk factors | OR | Standard deviation | Interval 95% | p value (unilateral) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.6548 | 0.7746 | (0.0658-2.671) | 0.1775 |

| Age | 1.028 | 0.0406 | (0.9403-1.11) | 0.2335 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.9708 | 0.9767 | (0.1444-3.476) | 0.325 |

| Peritoneal dissemination | 9.931 | 17.28 | (0.5921-50.86) | 0.0684 |

| Liver metastasis | 1.898 | 3.631 | (0.0928-9.343) | 0.4729 |

| H-P | 0.8273 | 0.9917 | (0.0657-3.368) | 0.746 |

| CT type | 3.538 | 16.1 | (0.0978-21.18) | 0.4916 |

| G | 0.6282 | 0.4272 | (0.1636-1.679) | 0.1429 |

| Lauren classification | 5.396 | 12.7 | (0.2290-27.38) | 0.2123 |

| Cycle number | 1.945 | 0.5405 | (1.1330-3.228) | 0.006 |

| Tumor size | 1.117 | 0.2094 | (0.7524-1.563) | 0.3042 |

| TNM | 0.0948 | 0.1106 | (0.0097-0.3836) | 0.0017 |

Fig. 8.

Results of logistic regression – risk factors

Discussion

Gastric cancer was characterized by different mucus secretion, in relation to both quantitative and qualitative features. Mucin producing cancers are represented by ring-cell carcinoma and mucinous cancer. Mucin secreting cancer (MUC) in comparison with other histological types of gastric cancer is characterized by greater size, deeper invasion, and higher incidence of lymph node metastasis with higher rate of peritoneal dissemination [10].

Cancers with mucus secretion are more often observed in younger patients [7, 10]. In the present study there were no significant differences in MUC incidence by age. Both MUC and other histological types of gastric cancer were more often diagnosed in the age range of 40-60 years. MUC occurred more frequently in women. Other reports were similar [10]. In accessible data the presence of MUC was reported with different frequency, in some papers more often in men or with no significant differences by sex [10, 11].

The most common sites of gastric cancer are the pylorus (60%), fundus (20-30%) and cardia (5-20%) [2, 12]. In the present study, gastric cancer was most often found in the pylorus and additionally in multifocal location. Both histological types were found with the same frequency in the cardia and corpus. In the case of MUC there are contradictory data regarding its location. In many studies MUC is reported to be located in the distant part of the stomach [13]. Other authors reported no differences in tumor location.

In some studies, compared with NMUC, MUC clinicopathological features are reported to include macroscopically larger diameter and deeper invasion in the wall of the stomach [7]. In the analyzed groups we did not observe significant difference in tumor size between the groups. Considering the Lauren histological classification, the predominance of diffuse type was observed for MUC and intestinal type for gastric cancer without mucin (NMUC).

The TNM-UICC/AJCC classification had prognostic significance for patients and an influence on therapeutic decisions. In the whole group of patients, those with clinical stage IV were most numerous, both in MUC and in NMUC. However, stage IV was more often found in patients with NMUC and stage II-III in patients with MUC.

Regardless of histological type, gastric cancer infiltrates the wall of the stomach, spreads into adjacent and distant lymph nodes and metastasizes [1–5]. Kawamura et al. analyzed two group of gastric cancer patients: 61 patients with diagnosis of MUC and 748 with NMUC. They reported a lower rate of liver metastasis in MUC than in NMUC patients (1.6% MUC and 4.5% NMUC) [11]. However, the results of other studies showed a lack of significant differences in remote metastasis rates between MUC and NMUC patients [7]. In our study we analyzed two equally numerous groups: MUC and NMUC. We found that liver metastases were observed more often in NMUC than in MUC. There is a significant correlation between NMUC subtype and liver metastasis. Regarding presence of peritoneal dissemination and lymph node metastasis, their presence has been reported most often in MUC [7, 11, 12]. In some studies a relationship between lymph node metastasis and cancer depth has been reported: 33.3% for sm (the submucosa), 55.6% for mp (the muscularis propria), 66.7% for ss (the subserosa) and 73.6% for se (the serosa). In the case of patients with MUC, lymph node metastasis was more frequently seen in patients with cancer deeper in the stomach wall [14].

There are different opinions regarding prognosis in patients with MUC. In some papers no significant differences between prognosis and histological type MUC and NMUC were found [7, 14]. However, some data reported worse prognosis of MUC because of the more advanced stage in this group [15, 16]. In most papers MUC histological type was not found to be a negative prognostic factor [16, 17]. MUC patients’ poor prognosis correlates with more advanced stage at diagnosis and with infiltration of serous membrane [17, 18]. Intramural and deep penetration in the wall of the stomach of gastric MUC makes detection of carcinoma in the early stage difficult [17]. Therapeutic plans and follow-up after surgical treatment in MUC and cancer without mucin production (NMUC) should remain the same [18].

Ability of mucus production and secretion by cells of gastric cancer is not unequivocally a negative prognostic factor. In the present analysis a significant relationship between NMUC type and presence of liver metastases was found (p = 0.001). There was no significant difference in survival rates between MUC and NMUC patients (p = 0.322). Gastric cancer patients’ (MUC or NMUC) worse prognosis correlates with advanced stage of disease, particularly with dissemination of cancer.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:765–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okines A, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A. ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;5(21 Suppl):50–4. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li C, Oh SJ, Kim S, Hyung WJ, Yan M, Zhu ZG, Noh SH. Macroscopic Borrmann type as a simple prognostic indicator in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Oncology. 2009;77:197–204. doi: 10.1159/000236018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauren P. The two histological main type of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goseki N, Takizawa T, Koike M. Differences in the mode of extension of gastric cancer classified by histological type: new histological classification of gastric carcinoma. Gut. 1992;33:606–12. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.5.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng HC, Zheng YS, Xia P, Xu XY, Xing YN, Takahashi H, Guan YF, Takano Y. The pathobiological behaviors and prognosis associated with Japanese gastric adenocarcinomas of pure WHO histological subtypes. Histol Histopathol. 2010;25:445–52. doi: 10.14670/HH-25.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adachi Y, Mori M, Kido A, Shimono R, Maehara Y, Sugimachi K. A clinicopathologic study of mucinous gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1992;69:866–71. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920215)69:4<866::aid-cncr2820690405>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JM, Jang YJ, Kim JH, Park SS, Park SH, Kim SJ, Mok YJ, Kim CS. Gastric cancer histology: clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic value. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:520–5. doi: 10.1002/jso.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobin LH, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumors. 5th ed. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1997. pp. 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawamura H, Kondo Y, Osawa S, et al. A clinicopathologic study of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2001;4:83–6. doi: 10.1007/pl00011728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Shin DW, Yoo CH, Kim CB, Min JS, Lee KS. Clinicopathologic characteristic of mucinous gastric adenocarcinoma. Yonsei Med J. 1999;40:99–106. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1999.40.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu CY, Yeh HZ, Shih RT, Chen GH. A clinicopathologic study of mucinous gastric carcinoma including multivariate analysis. Cancer. 1998;83:1312–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981001)83:7<1312::aid-cncr7>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woo LS, Kim DY, Kim YJ, Kim SK. Clinicopathologic features of mucinous gastric carcinoma. Dig Surg. 2002;19:286–90. doi: 10.1159/000064583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sassa H, Kino I. A comparative study on mucinous carcinoma of the stomach and large intestine. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1979;76:659–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koufuji K, Takeda J, Toyonaga A, Kodama I, Aoyagi K, Yano S, Ohta J, Shirouzu K. Mucinous adenocarcinoma of the stomach – clinicopathological studies. Kurume Med J. 1996;42:289–94. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.43.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang M, Zhu GY, Zhang HF, Gao HY, Han XF, Xue YW. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis of mucinous gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:64–7. doi: 10.1002/jso.21533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shibuya H, Nishida R, Koide S, Kurokawa J, Okita K. Clinicopathological study of mucinous gastric carcinoma. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 2000;89:273–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunisaki C, Akiyama H, Nomura M, Matsuda G, Otsuka Y, Ono HA, Shimada H. Clinicopathologic characteristics and surgical outcomes of mucinous gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:836–42. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]