Abstract

Although gamma interferon (IFN-γ) is a key mediator of antiviral defenses, it is also a mediator of inflammation. As inflammation can drive lentiviral replication, we sought to determine the relationship between IFN-γ-related host immune responses and challenge virus replication in lymphoid tissues of simian-human immunodeficiency virus 89.6 (SHIV89.6)-vaccinated and unvaccinated rhesus macaques 6 months after challenge with simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239. Vaccinated-protected monkeys had low tissue viral RNA (vRNA) levels, vaccinated-unprotected animals had moderate tissue vRNA levels, and unvaccinated animals had high tissue vRNA levels. The long-term challenge outcome in vaccinated monkeys was correlated with the relative balance between SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses and nonspecific IFN-γ-driven inflammation. Vaccinated-protected monkeys had slightly increased tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels and a high frequency of IFN-γ-secreting T cells responding to in vitro SIVgag peptide stimulation; thus, it is likely that they could develop effective anti-SIV cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo. In contrast, both high tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels and strong in vitro SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses were detected in lymphoid tissues of vaccinated-unprotected monkeys. Unvaccinated monkeys had increased tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels but weak in vitro anti-SIV IFN-γ T-cell responses. In addition, in lymphoid tissues of vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys, the increased IFN-γ mRNA levels were associated with increased Mig/CXCL9, IP-10/CXCL10, and CXCR3 mRNA levels, suggesting that increased Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 expression resulted in recruitment of CXCR3+ activated T cells. Thus, IFN-γ-driven inflammation promotes SIV replication in vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys. Unlike all unvaccinated monkeys, most monkeys vaccinated with SHIV89.6 did not develop IFN-γ-driven inflammation, but they did develop effective antiviral CD8+-T-cell responses.

Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) plays an important role in effective host immune responses against bacterial and viral infections. IFN-γ is critical for the induction of cell-mediated immunity, especially cytotoxic-T-cell (CTL) responses (8, 28, 53). Furthermore, IFN-γ is one of the main effector molecules released by CTLs after antigenic stimulation (8, 63). IFN-γ knockout mice are highly susceptible to viral infections (20, 58). Direct antiviral effects of IFN-γ, independent of CD8+-T-cell cytotoxicity, have also been demonstrated, but only in hepatitis B virus (31-33) and vaccinia virus (68) infections.

CD8-positive T cells are critical in the control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infections. The appearance of HIV- and SIV-specific CD8+ T cells in the acute stage of infection is associated with decreasing plasma viral RNA (vRNA) levels (14, 45, 57). The depletion of CD8+ T cells in the acute stage of SIV infection results in persistently high plasma vRNA levels (39, 72). Furthermore, in HIV-1-infected patients, CTL responses are preserved in asymptomatic HIV-1-infected individuals but not in HIV-1-infected patients who progress to AIDS (54, 59). Consistent with the critical role of CTL responses, HIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses are stronger in asymptomatic HIV-1-infected patients than in rapid progressors (44), and the impairment of IFN-γ T-cell responses in HIV and SIV infections is associated with disease progression (26, 79). In addition, in several SIV vaccine studies, protection was correlated with the induction of IFN-γ T-cell responses (4, 10). In fact, it has been proposed that the relative immunogenicities of HIV vaccine candidates can be evaluated by using a HIV peptide-specific IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay to enumerate antigen-specific T cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (69).

IFN-γ also plays an important role in innate host defenses. It is rapidly induced and secreted by NK cells after pathogen encounter by the host. Furthermore, macrophage and neutrophil activation by IFN-γ results in the secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha (64) and reactive oxygen intermediates (18, 19, 30). Thus, IFN-γ is a key mediator of inflammatory responses (8, 25). IFN-γ may also play a role in HIV pathogenesis, and increased levels of IFN-γ have been reported in the sera and lymphoid tissues of HIV-1-infected patients (38, 78). IFN-γ expression in lymphoid tissues is associated with the induction of the IFN-γ-inducible chemokines Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 in SIV-infected rhesus macaques. It has been proposed that the continuous secretion of these chemokines results in increased inflammation in lymphoid tissues that promotes increased viral replication and thus disease progression (66).

We have previously shown that the majority of rhesus macaques immunized with nonpathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus 89.6 (SHIV89.6) and subsequently challenged with pathogenic SIVmac239 can control challenge virus replication (3, 55). The analysis of immune responses in PBMC during the acute phase postchallenge (p.c.) showed that the relative strengths of SIV-specific CTL, as measured by 51Cr release assays, in the first few weeks p.c. significantly correlated with protection (3, 55).

The goal of the present study was to examine the role of IFN-γ immune responses in these same monkeys 6 months p.c. Importantly, because the loss of control of virus replication in the vaccinated-unprotected animals occurred relatively late after SIV challenge, the examination of lymphoid tissues 6 months p.c. is close to the time when challenge virus escape occurred. We found that the relatively high level of virus replication in the lymphoid tissues of vaccinated-unprotected monkeys was associated with increased IFN-γ mRNA levels and inflammation. The patterns of IFN-γ-driven inflammation were similar in all the vaccinated-unprotected animals, even though the time intervals between escape and euthanization were different in individual unprotected monkeys, suggesting that the inflammation developed soon after escape. Importantly, the relationship between virus replication and IFN-γ responses observed in lymphoid tissues during the chronic p.c. phase was not accurately reflected in PBMC. These findings have implications for understanding the nature of protective immunity in attenuated lentiviral vaccine systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were housed at the California National Primate Research Center in accordance with the regulations of the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care standards. All animals were negative for antibodies to HIV-2, SIV, type D retrovirus, and simian T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 at the time the study was initiated.

Immunization and challenge.

The immunization (SHIV89.6) and challenge (SIVmac239) protocol for the rhesus macaques used in the present study was described previously (3). Briefly, monkeys were immunized with SHIV89.6 and challenged intravaginally with SIVmac239 6 to 15 months postimmunization. Based on plasma vRNA levels, the vaccinated animals were categorized as vaccinated-protected and vaccinated-unprotected (3). The present study reports data for representative animals of both groups (vaccinated-protected monkeys, n = 20; vaccinated-unprotected monkeys, n = 11). In addition, nine representative unvaccinated SIVmac239-infected animals from the previous study were included.

Tissue collection.

At the time of euthanasia (6 months after SIVmac239 challenge) blood, spleen, and peripheral and genital lymph node samples were collected. The tissue samples were stored in RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, Tex.) at −20°C until RNA preparation was performed (see below). In addition, cell suspensions were prepared from whole blood, spleen, and peripheral and genital lymph nodes for IFN-γ ELISPOT and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. Tissue cell suspensions from lymph nodes were prepared by gently dissecting lymph nodes with scalpels in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gemini BioProducts, Calabasas, Calif.) (complete RPMI) and passing the cell homogenate through a cell strainer (Fisher, Pittsburgh, Pa.). The cells were washed twice by centrifugation for 10 min at 600 × g. Spleen tissue samples were cut into small pieces and homogenized using a syringe plunger. The homogenate was passed through a cell strainer. Splenic lymphocytes were isolated by gradient centrifugation with lymphocyte separation medium from ICN Biomedicals (Aurora, Ohio), followed by two washes with complete RPMI. PBMC were isolated from whole blood by using lymphocyte separation medium.

IFN-γ ELISPOT assay.

The numbers of IFN-γ-secreting cells in tissue cell suspensions in response to SIVmac239 Gag p27 peptide stimulation were determined with an IFN-γ monkey cytokine ELISPOT kit (U-CyTech; Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands) as described previously (3).

Phenotypic analysis of tissue cell populations.

The percentages of CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ T cells, and of CD20+ B cells, within the lymphocyte population were determined by FACS analysis on the FACSCalibur using rhesus macaque-specific antibodies from Pharmingen (San Jose, Calif.) (CD3 clone no. SP34, CD4 clone no. M-T477, and CD8 clone no. SK1) and Becton Dickinson (San Jose, Calif.) (CD20 clone no. L27). The percentage of activated T cells was determined by four-color FACS analysis using the following antibody combinations: (i) CD3-peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP), CD4-allophycocyanin (APC), CD8-phycoerythrin, and CD28-fluorescein isothiocyanate (clone no. L293; Becton Dickinson) and (ii) CD3-PerCP, CD4-APC, or CD8-APC; CD38-fluorescein isothiocyanate (the CD38 antibody was kindly provided by R. Reyes, Center for Comparative Medicine, University of California—Davis, Davis); HLA-DR- phycoerythrin (clone no. G46-6; Pharmingen). It should be noted that only very bright CD38-positive cells were counted. The frequencies of CD28, CD38, and HLA-DR-positive T cells were expressed as percentages of CD3+ CD4+ or CD3+ CD8+ T cells.

RNA isolation and cDNA preparation.

Total RNA was isolated with Trizol according to the manufacturer's instructions from tissue samples stored in RNAlater (Ambion). RNA samples were DNase treated with DNA-free (Ambion) for 1 h at 37°C. cDNA was prepared using random hexamer primers (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Piscataway, N.J.) and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen).

Cytokine and CXCR3 mRNA analysis by reverse transcriptase real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR was performed as previously described (1, 2). The primer-probe pairs for IFN-γ, Mig/CXCL9, IP-10/CXCL10, and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) have been published (2, 66). The following primer-probe pair (5′-3′) was used to amplify CXCR3 transcripts: forward primer, CAA CCA CAA GCA CCA AAG CA; reverse primer, GCA ACC TCG GCG TCA TTT; probe, FAM-CAC TCA CCT CAA GGA CCA TGG CTG G-TAMRA. Briefly, samples were tested in duplicate, and the PCRs for the housekeeping GAPDH gene and the target gene from each sample were run in parallel on the same plate. The reaction was carried out on a 96-well optical plate (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) in a 25-μl reaction volume containing 5 μl of cDNA plus 20 μl of Mastermix (Applied Biosystems). All sequences were amplified using the 7700 default amplification program: 2 min at 50°C and 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. The results were analyzed with the SDS 7700 system software, version 1.6.3 (Applied Biosystems).

Cytokine and CXCR3 mRNA expression levels were calculated from normalized ΔCt values (Ct values correspond to the cycle number at which the fluorescence due to enrichment of the PCR product reaches significant levels above the background fluorescence [threshold]) and are reported as the increase in cytokine and CXCR3 mRNA levels in tissues of vaccinated and unvaccinated monkeys compared to the average cytokine and CXCR3 mRNA levels in the same tissues of four uninfected (age-matched) animals. Note that it is not practical to obtain baseline biopsy samples from the spleen and many of the lymph nodes examined in this study, and thus, tissues from uninfected animals were chosen as controls to determine baseline cytokine and CXCR3 mRNA levels. In this analysis, the Ct value for the housekeeping (GAPDH) gene is subtracted from the Ct value of the target (cytokine) gene. The ΔCt value for the tissue samples from the uninfected animals is then subtracted from the ΔCt value of the corresponding tissue sample from the vaccinated or unvaccinated animal (ΔΔCt). Assuming that the target (cytokine) gene and the reference (GAPDH) gene are amplified with the same efficiency (data not shown), the increase in cytokine-CXCR3 mRNA levels in tissue samples of vaccinated and unvaccinated monkeys compared to those in tissue samples of uninfected animals is then calculated as follows: increase = 2−ΔΔCt (User Bulletin no. 2, ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System; Applied Biosystems).

ISH for Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 mRNAs.

Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 mRNAs were detected in rhesus macaque tissues using S35-labeled, macaque-derived, gene-specific riboprobes as described previously (66). Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized by heating them at 60°C for 15 min and incubating them twice for 8 min each time in xylene, followed by two rinses for 8 min each time in 95% ethanol and air drying. Tissue section pretreatment, ISH, washing, and emulsion autoradiography were performed as described previously (66). The autoradiographic exposure times were 14 days.

Detection of Mig/CXCL9 protein-positive cells.

The number of Mig/CXCL9-positive cells in lymphoid tissues was determined by immunohistochemistry; 4-μm-thick sections of paraffin-embedded tissue sections were rehydrated for 3 min with xylene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.). This process was repeated a total of three times, and then the slides were washed with ethanol as follows: 2 min at 100%, 2 min at 95%, 2 min at 80%, and 2 min at 50% ethanol. The slides were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (three times for 5 min each time). Next, a two-step antigen retrieval was performed for 3 min (microwave; full power) using a 1:10 dilution of AR-10 (BioGenex, San Ramon, Calif.), followed by 10 min with a 40% solution. After the slides were washed with PBS, they were incubated for 20 min with a peroxidase quenching solution (EM Science, Gibbstown, N.J.). Another wash with PBS followed. In the next step, the slides were incubated with goat anti-human biotinylated Mig/CXCL9 antibody (clone no. BAF392; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) in a humidity chamber. The antibody was diluted 1:25 in Hanks balanced salt solution (Invitrogen) supplemented with 0.1% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.01 M HEPES buffer (Roche, Indianpolis, Ind.), 0.002% sodium azide (Sigma), 2% normal horse serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.), and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma). After overnight incubation, the slides were washed three times (5 min each time) with Hanks balanced salt solution-0.1% saponin solution. Streptavidin-peroxidase (Zymed, South San Francisco, Calif.) was then added for 10 min, followed by three washes with PBS. The slides were developed by incubating them for 5 min with diaminobenzidine (Vector) and washing them with water. Then, the slides were stained for 1 min with Harris hematoxylin (Fisher). After dehydration, the slides were cover slipped. All steps were performed at room temperature if not otherwise indicated.

The slides were analyzed by capturing five random images on a Zeiss (Jena, Germany) Axioplan 2 microscope and using Open Image Analysis software (Improvision, Inc., Lexington, Mass.) as previously described (51). The Mig/CXCL9-positive cells per tissue section were manually counted and are reported as the number of Mig/CXCL9-positive cells per cubic millimeter (volume = tissue section area × thickness of tissue section).

Enumeration of SIV-infected cells.

The number of SIV-infected cells was determined on 6-μm-thick paraffin tissue sections by in situ hybridization (ISH) using eight digoxigenin-labeled probes (0.7 to 1.5 kb) spanning the whole SIVmac239 genome as previously described (35, 37). It should be noted that it was not possible to distinguish between cells infected with the vaccine virus, SHIV89.6, and cells infected with the challenge virus, SIVmac239. Negative controls for ISH were slides with SIV-negative tissue sections and slides with SIV-positive tissue sections but hybridized to SIV sense probes. To quantify the number of SIV-infected cells, the slides were counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red (Vector) after the ISH. The slides were viewed on a Zeiss Axiphot microscope and photographed with an AxioCam camera (Zeiss). SIV-positive slides were counted over the whole slide area, and a stereology grid was applied to measure the slide area. The frequency of SIV-positive cells is reported as the number of SIV-positive cells per cubic millimeter.

Virus load measurement.

Tissue RNA samples were analyzed for vRNA by a quantitative branched-DNA assay (P. J. Dailey, M. Zamround, R. Kelso, J. Kolberg, and M. Urdea, presented at the 13th Annu. Symp. Nonhum. Primate Models AIDS, Monterey, Calif., p. 180, 1995). The detection limit of this assay is 500 vRNA copies. Virus loads in tissue samples are reported as vRNA copy numbers per microgram of total tissue RNA.

Statistical analysis.

For statistical analysis, data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance, adjusting for multiple comparisons with Tukey's studentized range, using InStat software (Graph Pad Software Inc., San Diego, Calif.). Linear and nonlinear regression analyses were performed. The relationships between vRNA levels and IFN-γ mRNA levels and between vRNA levels and the frequency of IFN-γ-secreting T cells were analyzed with least-square regression models. Both quadratic and linear models were considered. If a significant quadratic term was found, the vRNA levels at which the response was maximized (or minimized) was estimated from the regression coefficients, and a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated from the estimated variance-covariance matrix using a first-order Taylor series expansion. In addition, correlations (Pearson correlations) between vRNA levels in different tissues and between IFN-γ mRNA levels and SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses in the same tissue were estimated. Analyses were carried out using InStat and S-plus (S-PLUS version 6.0; MathSoft, Inc., Seattle, Wash.) software. All tests were two sided at level 0.05.

RESULTS

vRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of SHIV89.6-vaccinated monkeys 6 months after intravaginal challenge with SIVmac239.

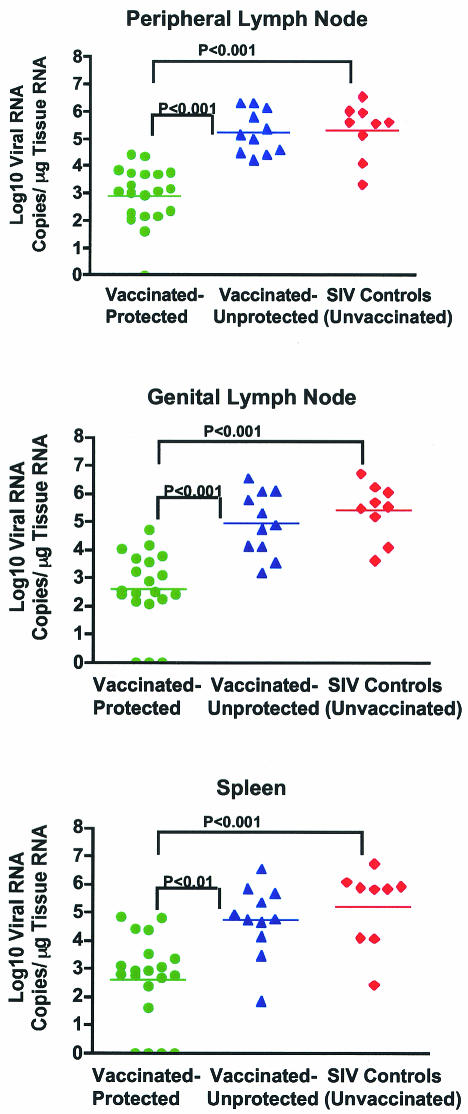

SHIV89.6-vaccinated rhesus macaques were grouped into vaccinated-protected and vaccinated-unprotected animals based on plasma vRNA levels after intravaginal challenge with SIVmac239 (3). Vaccinated-protected monkeys had plasma vRNA levels below 104 copies/ml throughout the 6-month p.c. period, whereas vaccinated-unprotected monkeys had plasma vRNA levels of >104 copies/ml at least once during the p.c. period (3). The vRNA levels in the spleen and axillary and genital lymph nodes were determined at 6 months p.c., and they were consistent with the prior categorization of individual monkeys into the vaccinated-protected and vaccinated-unprotected groups (3) (Fig. 1). Thus, vaccinated-protected monkeys had significantly lower vRNA levels in spleen, peripheral lymph nodes, and genital lymph nodes than vaccinated-unprotected (P < 0.01) and unvaccinated (P < 0.001) monkeys (Fig. 1). It should be noted that the branched-DNA assay does not distinguish between the vaccine and the challenge virus and that in the vaccinated-protected monkeys with no detectable plasma vRNA at any time p.c., vRNA was low but detectable in at least two of the three lymphoid tissues examined. There was no difference between tissue vRNA levels in vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

vRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of vaccinated and unvaccinated rhesus macaques 6 months after intravaginal challenge with SIVmac239. Tissue vRNA levels are expressed as log10 vRNA copies per microgram of total tissue RNA. Each symbol represents an individual animal. The horizontal line shows the mean vRNA copy number for each experimental group. Note that some vaccinated-protected monkeys had undetectable tissue vRNA in some tissue samples; however, vRNA was detected in at least two tissue samples from each animal.

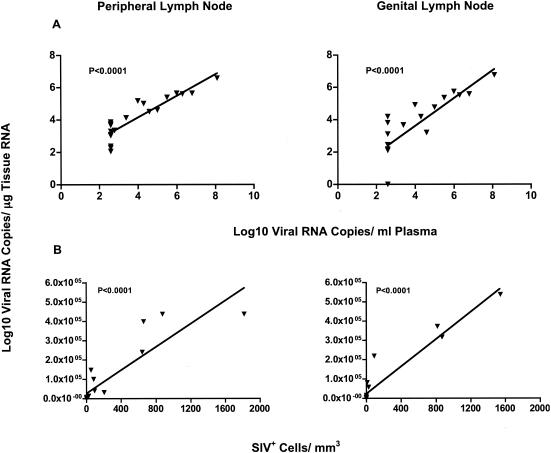

At 6 months p.c., plasma vRNA levels were an excellent indicator of overall viral replication, as there was a significant positive relationship between plasma vRNA and tissue vRNA levels (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between vRNA levels in peripheral and genital lymph nodes (r = 0.74; P < 0.001) and between spleen vRNA levels and vRNA levels in peripheral (r = 0.72; P < 0.001) and genital (r = 0.63; P < 0.001) lymph nodes.

FIG. 2.

Relationship among vRNA levels, plasma vRNA levels, and number of virus-positive cells in lymph nodes of vaccinated and unvaccinated rhesus macaques 6 months p.c. (A) Linear correlations between lymph node and plasma vRNA levels in vaccinated (vaccinated-protected, n = 9; vaccinated-unprotected, n = 5) and unvaccinated (n = 6) monkeys. Note that the monkeys with undetectable plasma vRNA levels were assigned plasma vRNA levels of 500 copies/ml, the detection limit of the assay. (B) Correlation between tissue vRNA levels and virus-positive cells determined by ISH (of the same monkey tissues graphed in panel A) is shown. Similar results were obtained in the spleen (data not shown).

Tissue vRNA levels also positively correlated with the number of SIV+ cells detected by ISH (Fig. 2B). SIV+ cells were undetectable if tissue vRNA levels were <7,500 vRNA copies/μg of tissue RNA and consistently detectable if tissue vRNA levels were >20,000 vRNA copies/μg of tissue RNA (data not shown). Thus, in lymphoid tissues of vaccinated-protected monkeys, only very few or no SIV+ cells were observed, while SIV+ cells were readily detectable in the majority of vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys (Fig. 2B).

Characterization of cell populations and lymphocyte activation in lymphoid tissues 6 months after intravaginal challenge with SIVmac239.

Consistent with our prior categorization of individual vaccinated monkeys as vaccinated-protected or vaccinated-unprotected animals based on plasma and tissue vRNA levels, the vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated animals had significantly reduced frequencies of CD4+ T cells in spleen and lymph nodes (P < 0.05) compared to vaccinated-protected monkeys (data not shown), whereas the percentages of CD8+ T cells in blood and tissues were similar in all three groups of monkeys (data not shown).

In blood and lymphoid tissues, there was an increased frequency of CD4+ HLA-DR+ and CD8+ HLA-DR+ T cells in vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys compared to vaccinated-protected animals (Table 1). Similarly, the average frequency of CD38+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was slightly higher in vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys than in vaccinated-protected monkeys (Table 1). Although the difference between the percentages of activated T cells (CD38+ and/or HLA-DR+) in vaccinated-protected and vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys did not always reach statistical significance (data not shown), there was a trend toward a higher percentage of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (CD38+ and/or HLA-DR+) in the tissues of the vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys.

TABLE 1.

Percentages of activated T cells in lymphoid tissues 6 months p.c.

| Activation marker | Challenge outcome | % Activated T cellsa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Spleen | Peripheral lymph node | Genital lymph node | ||

| CD4+ HLA-DR+ | Protected | 0.99 ± 0.59 | 3.02 ± 1.60 | 4.29 ± 1.88 | 2.38 ± 0.84 |

| Unprotected | 2.03 ± 1.53 | 2.99 ± 1.69 | 6.37 ± 2.09 | 3.93 ± 1.34 | |

| SIV controls | 2.78 ± 2.52 | 7.86 ± 2.98 | 4.07 ± 3.15 | 4.05 ± 1.82 | |

| CD4+ CD38+ | Protected | 3.50 ± 1.26 | 2.70 ± 0.53 | 2.62 ± 1.22 | 2.54 ± 0.97 |

| Unprotected | 5.42 ± 1.41 | 3.76 ± 1.49 | 3.83 ± 1.40 | 4.02 ± 1.88 | |

| SIV controls | 5.17 ± 0.99 | 4.03 ± 2.48 | 4.59 ± 1.75 | 4.51 ± 1.42 | |

| CD8+ HLA-DR+ | Protected | 3.90 ± 2.81 | 3.63 ± 2.79 | 6.53 ± 5.39 | 3.04 ± 1.68 |

| Unprotected | 3.04 ± 0.33 | 5.52 ± 1.89 | 6.58 ± 2.65 | 5.23 ± 1.88 | |

| SIV controls | 4.38 ± 4.16 | 7.72 ± 3.73 | 9.48 ± 4.99 | 7.11 ± 4.82 | |

| CD8+ CD38+ | Protected | 3.75 ± 2.27 | 2.77 ± 0.92 | 2.80 ± 1.26 | 2.31 ± 0.61 |

| Unprotected | 6.01 ± 5.78 | 3.30 ± 1.36 | 3.03 ± 0.86 | 3.40 ± 1.40 | |

| SIV controls | 6.05 ± 2.37 | 3.51 ± 0.79 | 4.03 ± 1.59 | 4.07 ± 1.92 | |

Data are expressed as mean percentages of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells ± standard deviation.

In all the animals, the T-cell costimulatory molecule CD28 was expressed in a lower frequency of T cells in the blood and spleen than in the T cells of peripheral and genital lymph nodes (data not shown). Vaccinated-protected, vaccinated-unprotected, and unvaccinated animals had similar mean frequencies of CD4+ CD28+ T cells in blood, spleen, and peripheral and genital lymph nodes. In contrast, unvaccinated animals had significantly fewer CD8+ CD28+ T cells in peripheral and genital lymph nodes (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3) than vaccinated-protected monkeys, while similar frequencies were found in blood and spleen. In fact, there was a significant negative correlation (P < 0.05) between the percentage of CD8+ CD28+ T cells and vRNA levels in peripheral and genital lymph nodes (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

CD28 expression on CD8+ T cells in genital (left) and peripheral (right) lymph nodes relative to tissue vRNA levels. Note that tissues of unvaccinated monkeys with the highest vRNA levels had lower frequencies of CD8+ CD28+ T cells. Green circles, vaccinated-protected monkeys; blue triangles, vaccinated-unprotected monkeys; red diamonds, unvaccinated monkeys.

IFN-γ mRNA levels and SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses in lymphoid tissues 6 months after intravaginal challenge with SIVmac239.

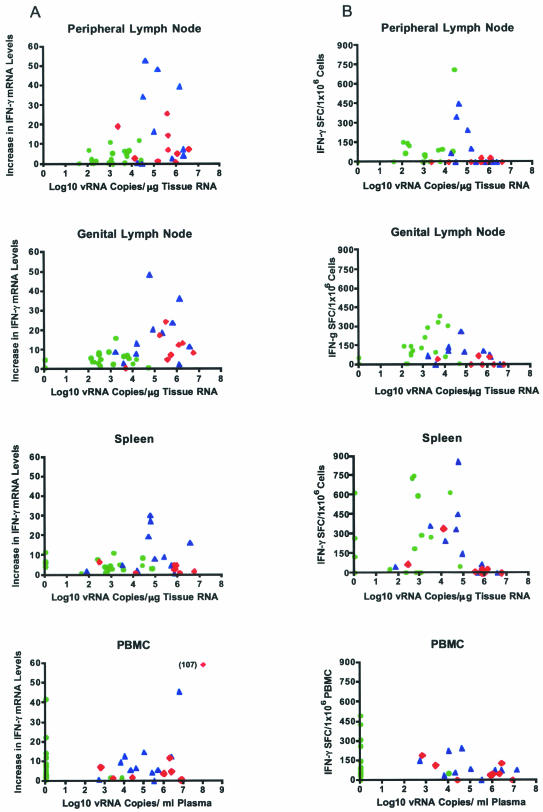

To define the relationship between IFN-γ mRNA levels and vRNA in lymphoid tissues during the chronic stages of infection p.c., the increase in tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels compared to IFN-γ mRNA levels in the same tissues of uninfected monkeys was plotted against tissue vRNA levels (Fig. 4A). Tissue samples with very low (<102 copies) or very high (>106 copies) vRNA levels had lower IFN-γ mRNA levels than tissues with moderate vRNA levels (102 to 105 copies) (Fig. 4A). Thus, IFN-γ mRNA levels were lowest in vaccinated-protected monkeys with low vRNA levels. Vaccinated-unprotected monkeys with intermediate to high levels of vRNA had the highest IFN-γ mRNA levels (Fig. 4A). In the unvaccinated animals, the IFN-γ mRNA levels were similar to the levels in vaccinated-unprotected animals, consistent with similar vRNA levels in both groups of monkeys (Fig. 4A). Statistical analysis found that the mean IFN-γ mRNA levels were significantly lower (P < 0.05) in the lymphoid tissues of the vaccinated-protected group of monkeys than in those of vaccinated-unprotected monkeys, but the mean IFN-γ mRNA levels were not statistically different in vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated animals.

FIG. 4.

Relationship between IFN-γ mRNA levels or SIVgag-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses and vRNA levels in tissues of vaccinated and unvaccinated monkeys 6 months p.c. (A) IFN-γ mRNA levels relative to vRNA levels and challenge outcome. (B) Frequency of SIVgag-specific IFN-γ-secreting cells relative to vRNA levels in individual monkeys with different challenge outcome. Individual vaccinated-protected (green circles), vaccinated-unprotected (blue triangles), and unvaccinated (red diamonds) monkeys are represented.

SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses in tissues were assessed using a SIVgag (p27) ELISPOT assay. The relationship of vRNA to the number of SIVgag-specific IFN-γ-secreting T cells responding to in vitro SIVgag peptide stimulation also showed that monkeys with intermediate levels of virus replication in their lymphoid tissues had the most consistent IFN-γ T-cell responses to SIV peptide stimulation (Fig. 4B). However, in contrast to IFN-γ mRNA levels, the mean numbers of IFN-γ-secreting T cells induced by SIV peptide stimulation were similar in vaccinated-protected and vaccinated-unprotected monkeys (Fig. 4B). Notably, 3 of 17 vaccinated-protected monkeys showed very strong SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses in the spleen despite the absence of detectable vRNA in the spleen. T cells from unvaccinated monkeys had a reduced potential to secrete IFN-γ in response to SIV peptides compared to those from vaccinated monkeys (Fig. 4B).

To define the statistical relationship between vRNA levels and IFN-γ mRNA levels and between vRNA levels and SIV-specific IFN-γ-secreting cells, linear and quadratic least-square regression models were fitted. With increasing vRNA levels, the levels of IFN-γ mRNA increased significantly in peripheral lymph nodes (P = 0.005) and in genital lymph nodes (P < 0.001), but not in the spleen. There was no significant tendency in any tissue toward a decline at the highest vRNA levels, as shown by quadratic coefficients that were not significantly different from zero. The plateau effect of IFN-γ mRNA levels observed at high vRNA levels was consistent with the group-specific analysis, which found no difference between either vRNA or IFN-γ mRNA levels in vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys.

In contrast, vRNA levels and SIV-specific IFN-γ-secreting T cells had a significant curvilinear relationship in peripheral lymph nodes (P = 0.017) and genital lymph nodes (P = 0.011). As vRNA levels increased, the average frequency of SIV-specific IFN-γ-secreting T cells first increased, then reached a plateau, and then decreased again at the highest vRNA levels. The peak frequencies of IFN-γ-secreting T cells were found at 3.38 log10 vRNA copies/μg of RNA (95% CI, 2.52 to 4.24 log10 vRNA copies/μg of RNA) in peripheral lymph nodes and at 3.33 log10 vRNA copies/μg of RNA (95% CI, 2.51 to 4.15 log10 vRNA copies/μg of RNA) in genital lymph nodes. A similar trend was observed in the spleen, but it did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.061).

Consistent with these findings, no significant correlation was found between IFN-γ mRNA levels and SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses in peripheral and genital lymph nodes, and only a modest correlation was observed in the spleen (r = 0.39; P = 0.02).

In summary, in the lymphoid tissues examined, different levels of virus replication (challenge outcome) were associated with different relationships between tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels and SIVgag-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses in vitro. Vaccinated-protected monkeys, had only slightly increased tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels. However, the strong in vitro SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses in these animals suggest that they can develop effective anti-SIV CTL responses in tissue. The persistence of actively replicating virus in lymphoid tissues of vaccinated-unprotected monkeys was reflected by the combination of markedly elevated IFN-γ mRNA levels and robust in vitro IFN-γ T-cell responses to SIVgag p27 stimulation. In contrast, despite increased tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels, the ability of T cells to secrete IFN-γ after in vitro SIVgag p27 stimulation was markedly reduced in unvaccinated compared to vaccinated-protected animals and to vaccinated-unprotected animals.

PBMC IFN-γ mRNA levels and SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses at 6 months p.c. with SIVmac239.

It has been shown that at 6 months p.c. PBMC IFN-γ mRNA levels were increased in ∼50% of the study monkeys and that this increase occurred independently of challenge outcome (3). As with the PBMC IFN-γ mRNA levels, in vitro SIVgag-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses in PBMC at 6 months p.c. were detected in similar percentages of vaccinated and unvaccinated monkeys (3). Despite undetectable plasma vRNA at 6 months p.c., vaccinated-protected monkeys had high PBMC IFN-γ mRNA levels and robust IFN-γ T-cell responses to in vitro SIVgag peptide stimulation (Fig. 4). Thus, at 6 months p.c., PBMC assays were unable to distinguish between vaccinated-protected and vaccinated-unprotected monkeys. Furthermore, the dependent relationship between IFN-γ mRNA levels or in vitro IFN-γ T-cell responses and tissue vRNA levels that we observed in lymphoid tissues (see above) was not detectable in paired PBMC samples (Fig. 4). Thus, PBMC IFN-γ responses did not reflect IFN-γ responses in the lymphoid tissues of the same monkey.

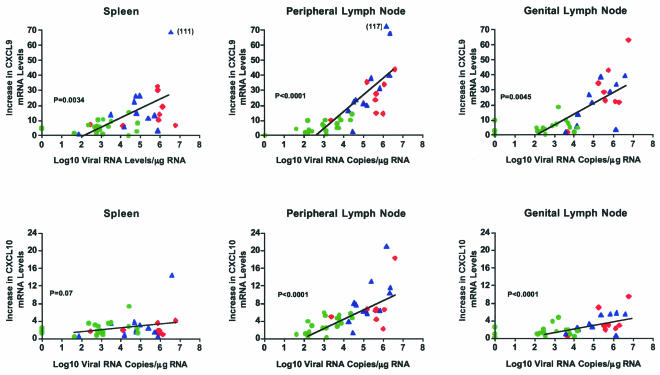

Levels of the IFN-γ-inducible proinflammatory chemokines Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 in lymphoid tissues correlate with tissue vRNA levels.

IFN-γ production results in the induction of various proinflammatory chemokines, including Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10. Consistent with the higher IFN-γ mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated animals, these animals also had increased Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA levels compared to the vaccinated-protected monkeys. The mean Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA levels in peripheral and genital lymph nodes of the vaccinated-protected monkeys were significantly lower than those in vaccinated-unprotected monkeys (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5). In the spleen, the vaccinated-protected monkeys had significantly lower mean Mig/CXCL9 mRNA levels than vaccinated-unprotected monkeys (P < 0.05) but similar mean IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA levels (Fig. 5). In fact, there was a strong positive correlation between tissue vRNA levels and Mig/CXCL9 mRNA levels in each of the lymphoid tissues examined (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Relationship between Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA and tissue vRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of vaccinated and unvaccinated monkeys 6 months p.c. The symbols are defined in the legend to Fig. 4.

The results of the PCR-based analysis of chemokine mRNA levels were confirmed by performing ISH for Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 in tissue sections from a subset of animals (Fig. 6 and data not shown). Thus, the number of ISH-positive Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 cells was highest in lymphoid tissues of unvaccinated monkeys and lowest in vaccinated-protected animals. Regardless of the degree of vaccine-mediated protection, Mig/CXCL9 mRNA+ cells were diffusely distributed within the paracortical regions of lymph nodes, with minimal localization of Mig/CXCL9 mRNA+ cells in medullary and follicular regions. IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA+ cells were also located in the paracortex but had a distinct multifocal distribution. In the spleen, Mig/CXCL9 mRNA+ cells were primarily located in the periarteriolar lymphoid sheath and were particularly common in the T-lymphocyte-rich marginal zone and mantle zone regions. IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA+ cells in the spleen had a distribution similar to that of Mig/CXCL9 mRNA+ cells. These findings are similar to those previously described for unvaccinated SIV/DeltaB670-infected macaques (66).

FIG. 6.

Frequency and anatomic distribution of SIV+, Mig/CXCL9+, and IP-10/CXCL10+ cells in the spleens of vaccinated and vaccine-naïve monkeys. (A, D, G, and J) Spleen from a representative vaccinated-protected animal (no. 28229). (B, E, H, and K) Spleen from a representative vaccinated-unprotected monkey (no. 30445). (C, F, I, and L) Spleen from a representative unvaccinated monkey (no. 28433). (A to C) SIV RNA-positive cells (large arrows) detected by ISH. Note that in unvaccinated monkeys, but not in vaccinated monkeys, vRNA is detectable as a diffuse fog of silver grains over follicular dendritic cells (small arrows). (D to F) ISH for IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA-positive cells. (G to I) ISH for Mig/CXCL9-positive cells. Fewer Mig/CXCL9-positive cells (arrows) were detected in the tissues of vaccinated monkeys than in those of unvaccinated animals. (J to L) Mig/CXCL9 protein-positive cells. Mig/CXCL9 protein-positive cells were rarely detectable in vaccinated-protected monkeys (J). The distribution of Mig/CXCL9-positive cells in vaccinated-unprotected monkeys (K) was predominantly in the white pulp. In contrast, Mig/CXCL9 protein-positive cells in unvaccinated animals (L) were detected in both the white and the red pulp (RP). Note the 100-μm scale bar in panel J.

Immunohistochemistry studies also confirmed the results from the chemokine mRNA analysis. The numbers of Mig/CXCL9 protein-positive cells in lymphoid tissues of vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated animals were significantly higher than the number of Mig/CXCL9-positive cells in tissues of vaccinated-protected monkeys (P < 0.05) (Table 2 and Fig. 6). Furthermore, the number of Mig/CXCL9-positive cells in the spleen and in peripheral and genital lymph nodes positively correlated with vRNA levels in the same tissues (P = 0.0008 and 0.021, respectively).

TABLE 2.

Mig/CXCL9 and CXCR3 expression in lymphoid tissues 6 months p.c.

| Animal no. | Challenge outcome | Expression

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral lymph node

|

Genital lymph node

|

Spleen

|

|||||

| Mig/CXCL9a | CXCR3b | Mig/CXCL9 | CXCR3 | Mig/CXCL9 | CXCR3 | ||

| 26640 | Vaccinated-protected | 53 | 1.41 | 800 | 2.93 | 225 | 1.20 |

| 28075 | 727 | 0.85 | 333 | 2.84 | 901 | 1.27 | |

| 28229 | 197 | 0.98 | 389 | 2.53 | 1,351 | 1.33 | |

| 31408 | 0 | 0.24 | 23 | 1.72 | 1,126 | 1.15 | |

| 23478 | 200 | ND | 146 | ND | 450 | ND | |

| 31420 | NDc | 1.76 | ND | 2.07 | ND | 1.73 | |

| Average | 235 | 1.05 | 338 | 2.42 | 235 | 1.05 | |

| SD | 289 | 0.58 | 297 | 0.52 | 289 | 0.58 | |

| 24196 | Vaccinated-unprotected | 3,210 | ND | 3,310 | ND | 5,180 | ND |

| 30445 | 2,727 | 4.42 | 6,786 | 4.64 | 4,054 | 2.55 | |

| 31413 | 1,550 | 2.38 | 2,038 | 4.70 | 4,730 | 1.43 | |

| 31411 | 3,976 | 1.88 | 4,338 | 3.16 | 901 | 2.08 | |

| 30474 | 1,605 | ND | 1,574 | ND | 5,631 | ND | |

| 31416 | ND | 1.78 | ND | 3.26 | ND | 2.07 | |

| Average | 2,614 | 2.62 | 3,609 | 3.94 | 3,609 | 3.94 | |

| SD | 1,046 | 1.23 | 2,081 | 0.84 | 2,081 | 0.84 | |

| 28048 | Unvaccinated | 2,758 | 1.92 | 2,720 | 4.23 | 4,730 | 2.34 |

| 27764 | 3,516 | 3.49 | 4,898 | 3.68 | 5,631 | 2.70 | |

| 28433 | 2,759 | 4.12 | 3,000 | 4.32 | 5,856 | 2.80 | |

| 25537 | 3,656 | 2.19 | 2,806 | 2.53 | 4,504 | 2.31 | |

| 23756 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4,955 | ND | |

| Average | 3,172 | 3.27 | 3,356 | 3.51 | 5,237 | 2.60 | |

| SD | 481 | 0.98 | 1,035 | 0.91 | 621 | 0.26 | |

Mig, Mig/CXCL9-positive cells per cubic millimeter (immunohistochemistry).

CXCR3, increase in CXCR3 mRNA levels compared to mRNA levels in the same tissues of uninfected monkeys.

ND, not done.

Expression levels of CXCR3, the receptor for Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10, correlate with vaccine outcome.

Increased Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA levels were associated with increased CXCR3 mRNA levels in the lymphoid tissues of vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated animals (Table 2). In all lymphoid tissues tested, vaccinated-unprotected monkeys had significantly higher mean mRNA levels of CXCR3 than vaccinated-protected monkeys (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Because CXCR3 is expressed by activated Th1 cells, this finding suggests that the increased Mig/CXCL9 mRNA expression in lymphoid tissues resulted in the recruitment of more activated CD4+ T cells. Unfortunately, an anti-CXCR3 reagent that could be used to determine the frequency of CXCR3+ T cells in lymphoid tissues was not available. However, the data suggest that persistent IFN-γ responses were associated with increased expression of the proinflammatory chemokines Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 and recruitment of activated T cells.

DISCUSSION

The understanding of how effective antiviral immune mechanisms induced by infection with a first lentivirus allow most monkeys to successfully control infection with a second pathogenic SIV should provide important insights into protective anti-SIV immunity and will also be of great relevance for vaccine design. The goal of the present study was to determine the relationship among virus replication, inflammation, and SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses in the lymphoid tissues of SHIV89.6-vaccinated and unvaccinated monkeys 6 months after challenge with pathogenic SIVmac239. In addition, we sought to determine if IFN-γ responses in lymphoid tissues (local responses) reflect the systemic responses measured in PBMC.

Lymphoid tissue vRNA levels in the study animals at 6 months p.c. supported the original categorization of the monkeys into vaccinated-protected and vaccinated-unprotected groups based on p.c. plasma vRNA levels (3). Thus, relative tissue vRNA levels among the animals were consistent with the relative plasma vRNA levels. The high levels of vRNA in spleen and peripheral and genital lymph nodes of unvaccinated and vaccinated-unprotected animals were associated with a concomitant and severe loss of CD4+ T cells. In the blood and lymphoid tissues of vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys, there was a trend toward increased frequencies of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing HLA-DR and CD38. Several other studies of HIV-1-infected patients, HIV-infected chimpanzees, and SIV-infected rhesus macaques have shown that increased numbers of HLA-DR- and CD38-positive T cells in the blood are associated with disease progression (27, 36, 46, 47, 60). The presence of higher frequencies of activated CD4+ T cells in lymphoid tissues of monkeys with higher vRNA levels (unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys) is consistent with the fact that CD4+-T-cell activation facilitates SIV replication. Increased expression of CD38 and HLA-DR on CD8+ T cells in blood and lymphoid tissues reflects the activation of these cells as they develop into CTL effector cells (36). However, increased frequencies of activated CD8+ CD38+ T cells in the blood of HIV-infected patients are associated with disease progression (9, 47, 50, 71). Vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated animals had higher numbers of CD8+ CD38+ T cells in PBMC and lymphoid tissues than the vaccinated-protected animals, which is consistent with the finding that although activated, these cells are not effective anti-HIV CTL (27).

The role of IFN-γ in HIV disease remains undefined. IFN-γ protein levels are increased in the serum and lymphoid tissues of HIV-1-infected patients compared to healthy controls, although the loss of HIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses is associated with disease progression (38, 78). Furthermore, IFN-γ mRNA levels are increased in blood and lymph nodes of HIV-1-infected patients (11, 29), and it has been suggested that the relative increase in IFN-γ mRNA levels in PBMC is related to the plasma vRNA levels in these patients (11). Similarly, IFN-γ mRNA levels are increased in PBMC and lymph nodes of acutely SIV-infected macaques (42, 66, 81) and persist throughout the course of infection (61).

To clarify the role of IFN-γ in SHIV89.6-mediated protection and disease progression, IFN-γ mRNA levels and SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses were determined in the same samples. Vaccinated-protected monkeys with low vRNA levels in lymphoid tissues had only slightly increased tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels and strong IFN-γ T-cell responses to SIVgag peptide stimulation in vitro. Tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels and in vitro SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses to peptide stimulation were both consistently increased in vaccinated-unprotected monkeys with intermediate to high vRNA levels. In contrast, unvaccinated animals had high levels of vRNA in lymphoid tissues, increased tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels, and a reduced ability of T cells to respond to in vitro SIVgag peptide stimulation. Thus, there was a discordance between virus-induced tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels and the SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses in vitro. This discordance was confirmed by statistical analysis and was most obvious when the vRNA levels in the lymphoid tissues were either very high or very low. Based on these findings, we propose that in vitro antigen-specific T-cell responses reflect the potential of an animal to develop anti-SIV CD8+-T-cell responses in lymphoid tissues and that the tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels reflect the amount of ongoing virus-induced inflammation in the same tissues. The latter is consistent with the recently proposed model in which infection with SIV might initiate IFN-γ-driven chronic inflammation (66). Thus, low levels of virus replication are associated with effective anti-SIV T-cell immunity (robust SIV p27-specific T-cell IFN-γ responses) without any inflammation contributing to pathogenesis. The most robust T-cell IFN-γ responses are induced in tissues with intermediate levels of virus replication.

To our knowledge, this is the first study showing that in lymphoid tissues there is a significant correlation between SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses and vRNA levels that is characterized by an increasing frequency (positive correlation) of IFN-γ-secreting cells at low to intermediate vRNA levels (up to 4.2 log10 vRNA copies/μg of RNA) but a decrease (negative correlation) in the number of SIV-specific IFN-γ-secreting T cells at higher vRNA levels. In tissues with very high vRNA levels, inflammation (increased IFN-γ mRNA levels; also see below) may drive pathogenesis and thereby result in suppression of effective anti-SIV immunity. This lack of CD8+-T-cell IFN-γ responses can also be explained by preferential infection and killing of SIV-specific CD4+ T helper cells, which are critical for the induction of CD8+-T-cell responses, as has been reported for HIV-1 infection (21, 40, 41). It is critical to note that most animals vaccinated with SHIV89.6 did not develop the inflammatory response to SIV challenge that was associated with uncontrolled virus replication and vaccine failure.

Associated with the loss of SIV-specific T-cell responses in unvaccinated monkeys, there was a strong negative correlation between lymph node vRNA levels and the percentage of CD8+ CD28+ T cells. It has been documented that progression to AIDS in HIV-1-infected patients and SIV-infected monkeys is associated with loss of CD28+ CD8+ T cells in blood and lymph nodes (5, 15, 16, 23, 46, 76, 77). CD28 is an important costimulatory molecule on T cells that interacts with CD80 on the antigen-presenting cells and amplifies TCR-dependent signals (17). The loss of CD28 expression on CD8+ T cells is typically observed after T-cell activation when CD8+ T cells develop into effector cells (5, 12, 15, 16, 34, 56, 65, 67, 76, 77). It has been suggested that increased numbers of terminally differentiated CD8+ CD28− effector T cells in HIV-1 infection are due to chronic activation as a result of continuous virus replication (15, 16). This conclusion is consistent with significantly lower frequencies of CD8+ CD28− T cells and lower levels of HLA-DR and CD38 expression on T cells in the lymph nodes of vaccinated-protected monkeys than in those of vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys.

In the blood of HIV-1-infected patients, CD8+ CD28− T cells are the main HIV-specific IFN-γ-producing cells (15, 16, 24, 75). At the same time, the loss of the CD28 molecule on CD8+ T cells is associated with a reduced proliferative potential and reduced interleukin-2 production (5, 23, 24, 76, 77). Thus, despite the ability to secrete IFN-γ, CD8+ CD28− T cells are functionally impaired and often show reduced cytolytic activity. In fact, with progression to disease, CD8+ CD28− T cells also lose the ability to produce IFN-γ (73). Although the present study did not determine if the CD8+ CD28− T cells were responsible for IFN-γ secretion or increased tissue IFN-γ mRNA levels, our data are consistent with that hypothesis. Thus, unvaccinated monkeys had increased CD8+ CD28− T-cell frequencies in lymphoid tissues but reduced IFN-γ T-cell responses to in vitro SIVgag peptide stimulation compared to vaccinated animals. Numerous other studies have demonstrated that loss of IFN-γ T-cell responses in HIV-1-infected patients or SIV-infected rhesus macaques is associated with disease progression (26, 44, 79).

IFN-γ induces several chemokines (7). In viral infections, locally produced IFN-γ results in the induction of Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 (13). It has been proposed that increased levels of Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 in lymphoid tissues of SIV-infected monkeys are associated with inflammation and thus disease progression (66). In the present study, we found that the increased IFN-γ mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of vaccinated-unprotected monkeys were associated with the induction of Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 mRNAs. Vaccinated-unprotected animals had the highest IFN-γ mRNA levels in spleen and lymph nodes, and the Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA levels were also increased. However, the greatest increase in Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA levels was seen in the spleens and lymph nodes of unvaccinated monkeys. While these tissues had increased IFN-γ mRNA levels, they did not reach the levels in vaccinated-unprotected monkeys. Thus, there was a clear positive correlation between tissue vRNA levels and Mig/CXCL9 mRNA and Mig/CXCL9 protein expression. Similarly, there was also a positive correlation between IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA levels and vRNA levels in lymph nodes. While increased IFN-γ mRNA levels provide the simplest explanation for the increased Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues, the relationship between IFN-γ and Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10 mRNA levels was not absolute, as vaccinated-unprotected monkeys had higher IFN-γ mRNA levels but less associated inflammation than unvaccinated monkeys. The direct induction of these proinflammatory chemokines by SIV in the unvaccinated animals cannot be ruled out. In fact, it has been shown that Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 can be induced directly by HIVgp120 and by double-stranded RNA (6, 48).

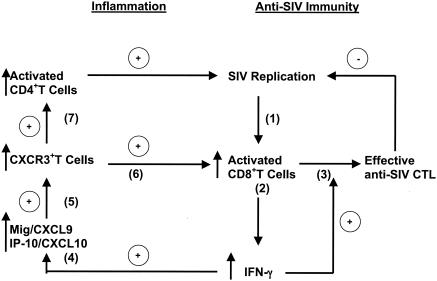

Both Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 have been implicated in antiviral host immune responses, presumably by influencing cell trafficking and cell-cell interactions (22, 49, 52, 62, 70, 80). Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 attract cells expressing CXCR3, a chemokine receptor selectively expressed on activated, but not resting, T cells (7, 43, 52). Indeed, we found that the increased Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 mRNA levels in vaccinated-unprotected and vaccine-naïve monkeys were associated with increased CXCR3 mRNA levels in matched tissue samples from individual animals. Thus, Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 likely contributed to the recruitment of activated T cells to lymphoid tissues. However, because both activated CD8+ and CD4+ T cells are recruited, Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 expression can promote ongoing viral replication (Fig. 7). In the animals in this study, the net effect of increased Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 expression seemed to be deleterious and not associated with effective cellular immune responses, because the highest levels of these proinflammatory chemokines were found in lymphoid tissues with higher vRNA levels. The critical role of virus-induced inflammation in promoting SIV pathogenesis is underlined by the fact that in sooty mangabeys, natural hosts for SIV, high plasma vRNA levels are maintained in the absence of generalized immune activation and associated bystander immunopathology (74).

FIG. 7.

Schematic representation of the proposed relationship among virus replication, IFN-γ-driven inflammation, and IFN-γ-induced effective anti-SIV CD8+-T-cell responses. Infection of rhesus macaques with SIV (step 1) results in the activation of CD8+ T cells (step 2), which secrete IFN-γ. IFN-γ drives the expansion and terminal differentiation of effective anti-SIV CTL (step 3), which are important in the control of virus replication. However, IFN-γ secretion also results in the induction of the proinflammatory chemokines Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL9 (step 4). These chemokines attract activated CXCR3+ T cells (step 5) to the area of virus replication. These CXCR3+ T cells include activated SIV-specific CD8+ T cells (step 6) that can promote further IFN-γ production (positive feedback loop) and contribute to effective anti-SIV immunity. However, CXCR3+ CD4+ T cells are also recruited, and these activated T helper cells are substrates for virus replication (step 7). This cycle of inflammation occurs in essentially all unvaccinated animals after SIVmac239 infection. In SHIV89.6-vaccinated monkeys, IFN-γ-driven inflammation was present only in the lymphoid tissues of animals that were not protected from SIV challenge. Thus, IFN-γ-driven inflammation can directly contribute to viral replication and to the observed inability of prior lentiviral infection to protect some individuals from subsequent challenge with a pathogenic virus.

Importantly, this is the first study showing that vaccination with an attenuated lentivirus can prevent the IFN-γ-driven inflammation that occurs in essentially all of the unvaccinated monkeys after pathogenic SIV challenge. In SHIV89.6-vaccinated monkeys, IFN-γ-driven inflammation was present only in the lymphoid tissues of the animals that were not protected from SIV challenge. Furthermore, the onset of uncontrolled viral replication occurred much later in vaccinated-unprotected monkeys than in unvaccinated animals, indicating that the immune escape occurred relatively late after challenge (3). Thus, IFN-γ-driven inflammation can directly contribute to viral replication and to the observed inability of prior lentiviral infection to protect some individuals from subsequent challenge with a pathogenic virus.

The relationship of IFN-γ mRNA levels or in vitro IFN-γ responses relative to tissue vRNA levels that we observed in lymphoid tissues was not detectable in PBMC. In fact, increased in vivo PBMC IFN-γ mRNA levels and in vitro IFN-γ T-cell secretion in response to SIVgag peptide stimulation were detected in similar percentages and at similar magnitudes in vaccinated-protected, vaccinated-unprotected, and unvaccinated monkeys. Thus, in contrast to IFN-γ responses measured in lymphoid tissues of the same monkey, PBMC IFN-γ responses at 6 months p.c. did not correlate with challenge outcome. These findings have implications for vaccine studies using PBMC-based immunological assays for the assessment of anti-HIV-SIV immunity.

The present study demonstrates that the long-term outcome of SIV challenge in monkeys vaccinated with live, virulence-attenuated SHIV89.6 is associated with the relative strength of SIV-specific IFN-γ T-cell responses versus nonspecific IFN-γ-driven inflammation. In most monkeys, SHIV89.6 vaccination reverses this balance between inflammation and anti-SIV immunity so that little inflammation will occur but strong anti-SIV T-cell immunity develops (Fig. 7). Vaccinated-protected monkeys had little inflammation in lymphoid tissues and strong in vitro T-cell responses to SIV peptide stimulation. One effect of increased inflammation in tissues of vaccinated-unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys was increased IFN-γ-induced expression of Mig/CXCL9 and IP-10/CXCL10 and recruitment of activated CXCR3+ T cells. Thus, the inflammatory response that is critical for the induction of effective antiviral cellular immune responses enhances SIV replication in unvaccinated and vaccinated-unprotected monkeys. By an as-yet-undefined mechanism, most monkeys vaccinated with live attenuated SHIV89.6 mounted effective antiviral CD8+-T-cell responses while avoiding the self-destructive inflammatory cycle found in the lymphoid tissues of unprotected and unvaccinated monkeys. The mechanism(s) by which the vaccine induces this condition and prevents disease progression is under investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Judy Li for help with the statistical analysis and Mike McChesney for helpful discussions. Kristen Bost, Lara Compton, Rino Dizon, Linda Fritts, Sajjad Khan, Ding Lu, and Blia Vang provided excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by Public Health Science grant RR00169, grant RR14555 from the National Center for Research Resources, and grant AI44480 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abel, K., M. J. Alegria-Hartman, K. Rothaeusler, M. Marthas, and C. J. Miller. 2002. The relationship between simian immunodeficiency virus RNA levels and the mRNA levels of alpha/beta interferons (IFN-alpha/beta) and IFN-alpha/beta-inducible Mx in lymphoid tissues of rhesus macaques during acute and chronic infection. J. Virol. 76:8433-8445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abel, K., M. J. Alegria-Hartman, K. Zanotto, M. B. McChesney, M. L. Marthas, and C. J. Miller. 2001. Anatomic site and immune function correlate with relative cytokine mRNA expression levels in lymphoid tissues of normal rhesus macaques. Cytokine 16:191-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abel, K., L. Compton, T. Rourke, D. Montefiori, D. Lu, K. Rothaeusler, L. Fritts, K. Bost, and C. J. Miller. 2003. Simian-human immunodeficiency virus SHIV89.6-induced protection against intravaginal challenge with pathogenic SIVmac239 is independent of the route of immunization and is associated with a combination of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte and alpha interferon responses. J. Virol. 77:3099-3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen, T. M., T. U. Vogel, D. H. Fuller, B. R. Mothe, S. Steffen, J. E. Boyson, T. Shipley, J. Fuller, T. Hanke, A. Sette, J. D. Altman, B. Moss, A. J. McMichael, and D. I. Watkins. 2000. Induction of AIDS virus-specific CTL activity in fresh, unstimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes from rhesus macaques vaccinated with a DNA prime/modified vaccinia virus Ankara boost regimen. J. Immunol. 164:4968-4978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appay, V., P. R. Dunbar, M. Callan, P. Klenerman, G. M. Gillespie, L. Papagno, G. S. Ogg, A. King, F. Lechner, C. A. Spina, S. Little, D. V. Havlir, D. D. Richman, N. Gruener, G. Pape, A. Waters, P. Easterbrook, M. Salio, V. Cerundolo, A. J. McMichael, and S. L. Rowland-Jones. 2002. Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nat. Med. 8:379-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asensio, V. C., J. Maier, R. Milner, K. Boztug, C. Kincaid, M. Moulard, C. Phillipson, K. Lindsley, T. Krucker, H. S. Fox, and I. L. Campbell. 2001. Interferon-independent, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120-mediated induction of CXCL10/IP-10 gene expression by astrocytes in vivo and in vitro. J. Virol. 75:7067-7077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baggiolini, M., B. Dewald, and B. Moser. 1994. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines—CXC and CC chemokines. Adv. Immunol. 55:97-179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billiau, A. 1998. Interferon-gamma, the TH1/TH2 paradigm in autoimmunity. Bull. Mem. Acad. R. Med. Belg. 153:231-233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouscarat, F., M. Levacher, M. C. Dazza, F. Chau, B. Desforges, M. Muffat-Joly, S. Matheron, P. M. Girard, and M. Sinet. 1999. Prospective study of CD8+ lymphocyte activation in relation to viral load in HIV-infected patients with ≥400 CD4+ lymphocytes per microliter. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:1419-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyer, J. D., A. D. Cohen, K. E. Ugen, R. L. Edgeworth, M. Bennett, A. Shah, K. Schumann, B. Nath, A. Javadian, M. L. Bagarazzi, J. Kim, and D. B. Weiner. 2000. Therapeutic immunization of HIV-infected chimpanzees using HIV-1 plasmid antigens and interleukin-12 expressing plasmids. AIDS 14:1515-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breen, E. C., J. F. Salazar-Gonzalez, L. P. Shen, J. A. Kolberg, M. S. Urdea, O. Martinez-Maza, and J. L. Fahey. 1997. Circulating CD8 T cells show increased interferon-gamma mRNA expression in HIV infection. Cell Immunol. 178:91-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgisser, P., C. Hammann, D. Kaufmann, M. Battegay, and O. T. Rutschmann. 1999. Expression of CD28 and CD38 by CD8+ T lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection correlates with markers of disease severity and changes towards normalization under treatment. The Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 115:458-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colditz, I. G., and D. L. Watson. 1992. The effect of cytokines and chemotactic agonists on the migration of T lymphocytes into skin. Immunology 76:272-278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daar, E. S. 1998. Virology and immunology of acute HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14(Suppl. 3):S229-S234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalod, M., M. Dupuis, J. C. Deschemin, D. Sicard, D. Salmon, J. F. Delfraissy, A. Venet, M. Sinet, and J. G. Guillet. 1999. Broad, intense anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) ex vivo CD8+ responses in HIV type 1-infected patients: comparison with anti-Epstein-Barr virus responses and changes during antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 73:7108-7116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalod, M., M. Sinet, J. C. Deschemin, S. Fiorentino, A. Venet, and J. G. Guillet. 1999. Altered ex vivo balance between CD28+ and CD28− cells within HIV-specific CD8+ T cells of HIV-seropositive patients. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:38-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis, S. J., S. Ikemizu, E. J. Evans, L. Fugger, T. R. Bakker, and P. A. van der Merwe. 2003. The nature of molecular recognition by T cells. Nat. Immunol. 4:217-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeMayer, D.-G. 1998. The cytokine handbook, p. 491-516. In Angus W. Thomson (ed.), Cytokine handbook, 3rd ed. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 19.de Metz, J., C. E. Hack, J. A. Romijn, M. Levi, T. A. Out, I. J. ten Berge, and H. P. Sauerwein. 2001. Interferon-gamma in healthy subjects: selective modulation of inflammatory mediators. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 31:536-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dittmer, U., K. E. Peterson, R. Messer, I. M. Stromnes, B. Race, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2001. Role of interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-12, and gamma interferon in primary and vaccine-primed immune responses to Friend retrovirus infection. J. Virol. 75:654-660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Douek, D. C., L. J. Picker, and R. A. Koup. 2003. T cell dynamics in HIV-1 infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:265-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dufour, J. H., M. Dziejman, M. T. Liu, J. H. Leung, T. E. Lane, and A. D. Luster. 2002. IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10; CXCL10)-deficient mice reveal a role for IP-10 in effector T cell generation and trafficking. J. Immunol. 168:3195-3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Effros, R. B., R. Allsopp, C. P. Chiu, M. A. Hausner, K. Hirji, L. Wang, C. B. Harley, B. Villeponteau, M. D. West, and J. V. Giorgi. 1996. Shortened telomeres in the expanded CD28−CD8+ cell subset in HIV disease implicate replicative senescence in HIV pathogenesis. AIDS 10:F17-F22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eylar, E. H., C. Lefranc, I. Baez, S. L. Colon-Martinez, Y. Yamamura, N. Rodriguez, N. Yano, and T. B. Breithaupt. 2001. Enhanced interferon-gamma by CD8+ CD28− lymphocytes from HIV+ patients. J. Clin. Immunol. 21:135-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrar, M. A., and R. D. Schreiber. 1993. The molecular cell biology of interferon-gamma and its receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11:571-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuller, M. J., and A. J. Zajac. 2003. Ablation of CD8 and CD4 T cell responses by high viral loads. J. Immunol. 170:477-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giorgi, J. V., and R. Detels. 1989. T-cell subset alterations in HIV-infected homosexual men: NIAID Multicenter AIDS cohort study. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 52:10-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giovarelli, M., A. Santoni, C. Jemma, T. Musso, A. M. Giuffrida, G. Cavallo, S. Landolfo, and G. Forni. 1988. Obligatory role of IFN-gamma in induction of lymphokine-activated and T lymphocyte killer activity, but not in boosting of natural cytotoxicity. J. Immunol. 141:2831-2836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graziosi, C., G. Pantaleo, K. R. Gantt, J. P. Fortin, J. F. Demarest, O. J. Cohen, R. P. Sekaly, and A. S. Fauci. 1994. Lack of evidence for the dichotomy of TH1 and TH2 predominance in HIV-infected individuals. Science 265:248-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenspan, H. C., and O. I. Aruoma. 1994. Oxidative stress and apoptosis in HIV infection: a role for plant-derived metabolites with synergistic antioxidant activity. Immunol. Today 15:209-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guidotti, L. G., K. Ando, M. V. Hobbs, T. Ishikawa, L. Runkel, R. D. Schreiber, and F. V. Chisari. 1994. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes inhibit hepatitis B virus gene expression by a noncytolytic mechanism in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:3764-3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guidotti, L. G., and F. V. Chisari. 1996. To kill or to cure: options in host defense against viral infection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 8:478-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guidotti, L. G., R. Rochford, J. Chung, M. Shapiro, R. Purcell, and F. V. Chisari. 1999. Viral clearance without destruction of infected cells during acute HBV infection. Science 284:825-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamann, D., P. A. Baars, M. H. Rep, B. Hooibrink, S. R. Kerkhof-Garde, M. R. Klein, and R. A. van Lier. 1997. Phenotypic and functional separation of memory and effector human CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 186:1407-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirsch, V. M., G. Dapolito, P. R. Johnson, W. R. Elkins, W. T. London, R. J. Montali, S. Goldstein, and C. Brown. 1995. Induction of AIDS by simian immunodeficiency virus from an African green monkey: species-specific variation in pathogenicity correlates with the extent of in vivo replication. J. Virol. 69:955-967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho, H. N., L. E. Hultin, R. T. Mitsuyasu, J. L. Matud, M. A. Hausner, D. Bockstoce, C. C. Chou, S. O'Rourke, J. M. Taylor, and J. V. Giorgi. 1993. Circulating HIV-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells express CD38 and HLA-DR antigens. J. Immunol. 150:3070-3079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu, J., M. Pope, C. Brown, U. O'Doherty, and C. J. Miller. 1998. Immunophenotypic characterization of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected dendritic cells in cervix, vagina, and draining lymph nodes of rhesus monkeys. Lab. Investig. 78:435-451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jassoy, C., T. Harrer, T. Rosenthal, B. A. Navia, J. Worth, R. P. Johnson, and B. D. Walker. 1993. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes release gamma interferon, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), and TNF-beta when they encounter their target antigens. J. Virol. 67:2844-2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin, X., D. E. Bauer, S. E. Tuttleton, S. Lewin, A. Gettie, J. Blanchard, C. E. Irwin, J. T. Safrit, J. Mittler, L. Weinberger, L. G. Kostrikis, L. Zhang, A. S. Perelson, and D. D. Ho. 1999. Dramatic rise in plasma viremia after CD8+ T cell depletion in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J. Exp. Med. 189:991-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalams, S. A., S. P. Buchbinder, E. S. Rosenberg, J. M. Billingsley, D. S. Colbert, N. G. Jones, A. K. Shea, A. K. Trocha, and B. D. Walker. 1999. Association between virus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte and helper responses in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 73:6715-6720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalams, S. A., and B. D. Walker. 1998. The critical need for CD4 help in maintaining effective cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J. Exp. Med. 188:2199-2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khatissian, E., M. G. Tovey, M. C. Cumont, V. Monceaux, P. Lebon, L. Montagnier, B. Hurtrel, and L. Chakrabarti. 1996. The relationship between the interferon alpha response and viral burden in primary SIV infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:1273-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim, C. H., and H. E. Broxmeyer. 1999. Chemokines: signal lamps for trafficking of T and B cells for development and effector function. J. Leukoc. Biol. 65:6-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kostense, S., G. S. Ogg, E. H. Manting, G. Gillespie, J. Joling, K. Vandenberghe, E. Z. Veenhof, D. van Baarle, S. Jurriaans, M. R. Klein, and F. Miedema. 2001. High viral burden in the presence of major HIV-specific CD8+ T cell expansions: evidence for impaired CTL effector function. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:677-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuroda, M. J., J. E. Schmitz, W. A. Charini, C. E. Nickerson, M. A. Lifton, C. I. Lord, M. A. Forman, and N. L. Letvin. 1999. Emergence of CTL coincides with clearance of virus during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus monkeys. J. Immunol. 162:5127-5133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuroda, M. J., J. E. Schmitz, W. A. Charini, C. E. Nickerson, C. I. Lord, M. A. Forman, and N. L. Letvin. 1999. Comparative analysis of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in lymph nodes and peripheral blood of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 73:1573-1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levacher, M., F. Hulstaert, S. Tallet, S. Ullery, J. J. Pocidalo, and B. A. Bach. 1992. The significance of activation markers on CD8 lymphocytes in human immunodeficiency syndrome: staging and prognostic value. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 90:376-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu, D., A. K. Cardozo, M. I. Darville, and D. L. Eizirik. 2002. Double-stranded RNA cooperates with interferon-gamma and IL-1 beta to induce both chemokine expression and nuclear factor-kappa B-dependent apoptosis in pancreatic beta-cells: potential mechanisms for viral-induced insulitis and beta-cell death in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinology 143:1225-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu, M. T., D. Armstrong, T. A. Hamilton, and T. E. Lane. 2001. Expression of Mig (monokine induced by interferon-gamma) is important in T lymphocyte recruitment and host defense following viral infection of the central nervous system. J. Immunol. 166:1790-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu, Z., L. E. Hultin, W. G. Cumberland, P. Hultin, I. Schmid, J. L. Matud, R. Detels, and J. V. Giorgi. 1996. Elevated relative fluorescence intensity of CD38 antigen expression on CD8+ T cells is a marker of poor prognosis in HIV infection: results of 6 years of follow-up. Cytometry 26:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma, Z., F. X. Lu, M. Torten, and C. J. Miller. 2001. The number and distribution of immune cells in the cervicovaginal mucosa remain constant throughout the menstrual cycle of rhesus macaques. Clin. Immunol. 100:240-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahalingam, S., J. M. Farber, and G. Karupiah. 1999. The interferon-inducible chemokines MuMig and Crg-2 exhibit antiviral activity in vivo. J. Virol. 73:1479-1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maraskovsky, E., W. F. Chen, and K. Shortman. 1989. IL-2 and IFN-gamma are two necessary lymphokines in the development of cytolytic T cells. J. Immunol. 143:1210-1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McChesney, M., F. Tanneau, A. Regnault, P. Sansonetti, L. Montagnier, M. P. Kieny, and Y. Riviere. 1990. Detection of primary cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for the envelope glycoprotein of HIV-1 by deletion of the env amino-terminal signal sequence. Eur. J. Immunol. 20:215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miller, C. J., M. B. McChesney, X. Lu, P. J. Dailey, C. Chutkowski, D. Lu, P. Brosio, B. Roberts, and Y. Lu. 1997. Rhesus macaques previously infected with simian/human immunodeficiency virus are protected from vaginal challenge with pathogenic SIVmac239. J. Virol. 71:1911-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Monteiro, J., F. Batliwalla, H. Ostrer, and P. K. Gregersen. 1996. Shortened telomeres in clonally expanded CD28−CD8+ T cells imply a replicative history that is distinct from their CD28+CD8+ counterparts. J. Immunol. 156:3587-3590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore, J. P., Y. Cao, D. D. Ho, and R. A. Koup. 1994. Development of the anti-gp120 antibody response during seroconversion to human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 68:5142-5155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muller, U., U. Steinhoff, L. F. Reis, S. Hemmi, J. Pavlovic, R. M. Zinkernagel, and M. Aguet. 1994. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science 264:1918-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ogg, G. S., X. Jin, S. Bonhoeffer, P. R. Dunbar, M. A. Nowak, S. Monard, J. P. Segal, Y. Cao, S. L. Rowland-Jones, V. Cerundolo, A. Hurley, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. F. Nixon, and A. J. McMichael. 1998. Quantitation of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and plasma load of viral RNA. Science 279:2103-2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O'Neil, S. P., F. J. Novembre, A. B. Hill, C. Suwyn, C. E. Hart, T. Evans-Strickfaden, D. C. Anderson, J. deRosayro, J. G. Herndon, M. Saucier, and H. M. McClure. 2000. Progressive infection in a subset of HIV-1-positive chimpanzees. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1051-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Orandle, M. S., K. C. Williams, A. G. MacLean, S. V. Westmoreland, and A. A. Lackner. 2001. Macaques with rapid disease progression and simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis have a unique cytokine profile in peripheral lymphoid tissues. J. Virol. 75:4448-4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Park, M. K., D. Amichay, P. Love, E. Wick, F. Liao, A. Grinberg, R. L. Rabin, H. H. Zhang, S. Gebeyehu, T. M. Wright, A. Iwasaki, Y. Weng, J. A. DeMartino, K. L. Elkins, and J. M. Farber. 2002. The CXC chemokine murine monokine induced by IFN-gamma (CXC chemokine ligand 9) is made by APCs, targets lymphocytes including activated B cells, and supports antibody responses to a bacterial pathogen in vivo. J. Immunol. 169:1433-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pasternack, M. S., M. J. Bevan, and J. R. Klein. 1984. Release of discrete interferons by cytotoxic T lymphocytes in response to immune and nonimmune stimuli. J. Immunol. 133:277-280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Philip, R., and L. B. Epstein. 1986. Tumour necrosis factor as immunomodulator and mediator of monocyte cytotoxicity induced by itself, gamma-interferon and interleukin-1. Nature 323:86-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pitcher, C. J., S. I. Hagen, J. M. Walker, R. Lum, B. L. Mitchell, V. C. Maino, M. K. Axthelm, and L. J. Picker. 2002. Development and homeostasis of T cell memory in rhesus macaque. J. Immunol. 168:29-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reinhart, T. A., B. A. Fallert, M. E. Pfeifer, S. Sanghavi, S. Capuano III, P. Rajakumar, M. Murphey-Corb, R. Day, C. L. Fuller, and T. M. Schaefer. 2002. Increased expression of the inflammatory chemokine CXC chemokine ligand 9/monokine induced by interferon-gamma in lymphoid tissues of rhesus macaques during simian immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Blood 99:3119-3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roos, M. T., R. A. van Lier, D. Hamann, G. J. Knol, I. Verhoofstad, D. van Baarle, F. Miedema, and P. T. Schellekens. 2000. Changes in the composition of circulating CD8+ T cell subsets during acute Epstein-Barr and human immunodeficiency virus infections in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 182:451-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ruby, J., and I. Ramshaw. 1991. The antiviral activity of immune CD8+ T cells is dependent on interferon-gamma. Lymphokine Cytokine Res. 10:353-358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Russell, N. D., M. G. Hudgens, R. Ha, C. Havenar-Daughton, and M. J. McElrath. 2003. Moving to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine efficacy trials: defining T cell responses as potential correlates of immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 187:226-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Salazar-Mather, T. P., T. A. Hamilton, and C. A. Biron. 2000. A chemokine-to-cytokine-to-chemokine cascade critical in antiviral defense. J. Clin. Investig. 105:985-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Savarino, A., F. Bottarel, F. Malavasi, and U. Dianzani. 2000. Role of CD38 in HIV-1 infection: an epiphenomenon of T-cell activation or an active player in virus/host interactions? AIDS 14:1079-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schmitz, J. E., M. J. Kuroda, S. Santra, V. G. Sasseville, M. A. Simon, M. A. Lifton, P. Racz, K. Tenner-Racz, M. Dalesandro, B. J. Scallon, J. Ghrayeb, M. A. Forman, D. C. Montefiori, E. P. Rieber, N. L. Letvin, and K. A. Reimann. 1999. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science 283:857-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shankar, P., M. Russo, B. Harnisch, M. Patterson, P. Skolnik, and J. Lieberman. 2000. Impaired function of circulating HIV-specific CD8+ T cells in chronic human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood 96:3094-4101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Silvestri, G., D. L. Sodora, R. A. Koup, M. Paiardini, S. P. O'Neil, H. M. McClure, S. I. Staprans, and M. B. Feinberg. 2003. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of sooty mangabeys is characterized by limited bystander immunopathology despite chronic high-level viremia. Immunity 18:441-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sousa, A. E., and R. M. Victorino. 1998. Single-cell analysis of lymphokine imbalance in asymptomatic HIV-1 infection: evidence for a major alteration within the CD8+ T cell subset. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 112:294-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Trimble, L. A., L. W. Kam, R. S. Friedman, Z. Xu, and J. Lieberman. 2000. CD3ζ and CD28 down-modulation on CD8 T cells during viral infection. Blood 96:1021-1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Trimble, L. A., P. Shankar, M. Patterson, J. P. Daily, and J. Lieberman. 2000. Human immunodeficiency virus-specific circulating CD8 T lymphocytes have down-modulated CD3ζ and CD28, key signaling molecules for T-cell activation. J. Virol. 74:7320-7330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]