Abstract

Virions of polyomaviruses consist of the major structural protein VP1, the minor structural proteins VP2 and VP3, and the viral genome associated with histones. An additional structural protein, VP4, is present in avian polyomavirus (APV) particles. As it had been reported that expression of APV VP1 in insect cells did not result in the formation of virus-like particles (VLP), the prerequisites for particle formation were analyzed. To this end, recombinant influenza viruses were created to (co)express the structural proteins of APV in chicken embryo cells, permissive for APV replication. VP1 expressed individually or coexpressed with VP4 did not result in VLP formation; both proteins (co)localized in the cytoplasm. Transport of VP1, or the VP1-VP4 complex, into the nucleus was facilitated by the coexpression of VP3 and resulted in the formation of VLP. Accordingly, a mutant APV VP1 carrying the N-terminal nuclear localization signal of simian virus 40 VP1 was transported to the nucleus and assembled into VLP. These results support a model of APV capsid assembly in which complexes of the structural proteins VP1, VP3 (or VP2), and VP4, formed within the cytoplasm, are transported to the nucleus using the nuclear localization signal of VP3 (or VP2); there, capsid formation is induced by the nuclear environment.

Polyomaviruses are nonenveloped icosahedral particles with a diameter of ∼45 nm containing a circular double-stranded DNA genome complexed with cellular histones (41). The capsid is composed of the major capsid protein VP1 and the two minor capsid proteins VP2 and VP3, which are expressed late in the viral replication cycle. VP3 is identical to the C-terminal region of VP2; translation is initiated by an internal initiation codon within the VP2-encoding region. Five molecules of VP1 assemble into a pentameric complex which interacts with one molecule of either VP2 or VP3, thus representing a capsomer of the polyomavirus particle. Infectious viral particles, consisting of 72 capsomers and the viral genome, are assembled within the nucleus of the infected cell. Although the structure of the polyomavirus particle has been well characterized by X-ray crystallography (18, 38), the detailed mechanisms of capsid assembly and the process of DNA packaging into the capsid are still subjects of intensive study (7, 15, 16).

Several polyomaviruses infecting different mammalian species have been described, including the human polyomaviruses JC virus (JCPyV) and BK virus (BKPyV), simian virus 40 (SV40), and the murine polyomavirus (MPyV) (41). Compared to these viruses, avian polyomavirus (APV) exhibits unique biological and structural characteristics: whereas mammalian polyomaviruses usually cause innocuous infections in their natural nonimmunocompromised hosts, APV is the causative agent of a fatal multisystemic disease in several species of birds (11, 14, 29, 34), observed all over the world. Recently, an additional structural protein, VP4, was identified within APV particles, a feature which is unique among the polyomaviruses (12). VP4 is essential for APV replication and interacts with VP1, as well as with double-stranded DNA. A leucine zipper motif that is considered to be responsible for DNA binding activity has been identified in VP4. Another outstanding feature of APV is the induction of apoptosis in tissue culture, conferred by VP4 and an internally truncated variant designated VP4Δ (10). VP4Δ has been observed only in infected cells (10).

The expression of VP1 proteins of a number of mammalian polyomaviruses in insect cells results in the formation of virus-like particles (VLP), similar to virions in size and shape (6, 21, 26, 33). In the case of APV, however, expression of VP1, either alone or after coexpression with VP2 and/or VP3, by recombinant-baculovirus-infected insect cells did not lead to VLP formation (1). Recently, VLP formation has been reported after recombinant expression of VP1 proteins of several polyomaviruses, including APV, in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (35). In this system, VLP formed by APV VP1 were generated; it was observed, however, that the efficacy of VLP formation was ∼10-fold lower than that of the mammalian polyomaviruses.

The results of these experiments indicate a possible significance of the cell type used for APV gene expression. In the present study, the prerequisites for the formation of APV VLP were analyzed in chicken embryo (CE) cells permissive for APV replication. Different combinations of the APV structural proteins, including VP4, were expressed using recombinant influenza viruses. The formation of VLP was observed, which correlated with the nuclear localization of VP1. Coexpression of VP3, but not the coexpression of VP4, proved to be a prerequisite for VLP formation. The results of these investigations give some insight into the mechanisms of APV capsid formation and might allow the development of an efficient and safe VLP-based APV vaccine, which is urgently needed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

The 293T cell line, maintained in Glasgow minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, was used for the generation of recombinant influenza viruses. Primary cultures of CE cells, prepared and maintained as described previously (22), were used for infection with APV strain BFDV-1 (39) or recombinant influenza viruses. Influenza A virus, strain FPV/Bratislava, was used as a helper virus. Infectivity titrations were performed as plaque assays.

Construction of transfer plasmids encoding APV-specific proteins.

Transfer plasmids for vRNA synthesis were generated using the vector pHL2139 (kindly provided by G. Hobom, Giessen, Germany) containing the influenza virus promoter flanked by promoter and terminator sequences for human RNA polymerase I (19). In order to generate negative-sense influenza virus RNA (vRNA) after transfection into CE cells, APV nucleotide sequences (31) were cloned in the antisense orientation with respect to the RNA polymerase I promoter. Briefly, the sequences encoding the APV structural proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3 were amplified by PCR using an APV full-length plasmid (pAPVinf [10]) as a template and the corresponding primers listed in Table 1. For PCR amplification of the sequences encoding VP4 and VP4Δ, the plasmids containing the corresponding cDNAs (p1a-E.coli or p1b-E.coli [12]) were used as templates. The PCR products were digested using combinations of AflIII and BglII in the case of VP1, NcoI and BamHI in the case of VP2 and VP3, or AflIII and BamHI in the case of VP4 and VP4Δ and subsequently ligated to the NcoI/BamHI-restricted vector pHL2139. The sequences of the transfer plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in PCR for construction of plasmids

| Designation | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Introduced restriction site |

|---|---|---|

| VP1-sb | GGCTACATGTCCCAAAAAGGAAAAGGAAGC | AflIII |

| VP1-asc | TGCGTCAGATCTATTTAGCGGGGA | BglII |

| VP1-NLS-s | GGCTCCATGGCACCTACTAAACGCAAAGGAAGCTGC | NcoI |

| VP2-s | CTAAGCCATGGGAGCTATCATTTCGGCTATAGC | NcoI |

| VP3-s | AACACCATGGCCCTACAGGTCTGGAGAGA | NcoI |

| VP2/3-as | GTTGGGATCCTATCTGGACCTGACTTTAC | BamHI |

| VP4/4Δ-s | CAACAACATGTCTACTCCAGCG | AflIII |

| VP4/4Δ-as | CGGGGGATCCTTAGCGAGCC | BamHI |

| VP1-tr-s | GGCTAGATCTATGTCCCAAAAAGGAAAAGG | BglII |

| VP4-tr-s | CCTTTGGATCCCATGTCTACTC | BamHI |

Introduced restriction sites are shown in italics, the respective start or stop codons are underlined, and exchanged or added codons in VP1-NLS-s are shown in boldface.

s, sense primer.

as, antisense primer.

Generation of VP1-NLSSV40.

A DNA fragment encoding VP1-NLSSV40, a mutant APV VP1 with the N-terminal part of the nuclear localization signal (NLS) of SV40 VP1, was generated by PCR essentially as described previously, using the mutagenic primer VP1-NLS-s (Table 1). The resulting PCR product was digested with NcoI and BglII and cloned into the NcoI/BamHI-restricted influenza virus transfer vector pHL2139. By this procedure, the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the expressed protein was changed from MSQKG to MAPTKR (exchanged and added amino acids are underlined).

Generation of recombinant influenza viruses.

Recombinant influenza viruses were generated essentially as described previously (19, 20, 24) and are presented schematically in Fig. 1. For the generation of recombinant influenza viruses, 50% confluent 293T cell cultures were transfected with the appropriate transfer plasmid, along with “booster” plasmids, using the Lipofectamine reagent (Life Technologies). Booster plasmids (kindly provided by G. Hobom) are eukaryotic expression vectors with genes coding for the proteins PA, PB1, PB2, and NP of the influenza virus nucleoprotein complex (25). The cells were incubated for 3 h with the transfection reagents; then, culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum was added. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the supernatants were removed and the cells were infected with influenza A virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 1 h at 37°C. Thereafter, the cells were washed once with culture medium and maintained in culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C until extensive cytopathic changes became visible. The supernatant containing the recombinant influenza viruses was collected and stored at −80°C.

FIG. 1.

Schematic presentation of the method used for the generation of recombinant influenza viruses. The transfer plasmid carrying the gene of interest is cotransfected into 293T cells, together with booster plasmids expressing influenza virus PA, PB1, PB2, and NP genes. After 24 h, during which the recombinant vRNA has been transcribed from the transfer plasmid, cells are infected with influenza helper virus for packaging of the vRNA. At 24 h after infection, the supernatant containing the recombinant influenza viruses is used for the infection of CE cells in which the gene of interest is expressed.

Infection of CE cells with recombinant influenza viruses.

CE cells maintained at 38°C were infected with the recombinant influenza viruses at an MOI of 1. For simultaneous multiple infections, individual recombinant influenza viruses were mixed and diluted to an MOI of 1 for each virus prior to infection of the cells. After infection for 1 h, the supernatant was removed and the cells were incubated in culture medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum at 38°C. For analysis of APV gene expression, cells grown on glass coverslips were investigated by immunofluorescence 8 h after infection. In all other cases, cells and debris were harvested by low-speed centrifugation 24 h after infection.

Transient expression of APV-specific proteins in CE cells.

The region encoding VP1 was amplified by PCR using the plasmid pAPVinf (10) as a template and the primers VP1-tr-s and VP1-as (Table 1), and the PCR product was digested using BglII. The VP4-encoding region was amplified by PCR using the plasmid p1a-E.coli (12) as a template and the primers VP4-tr-s and VP4/4Δ-as (Table 1), and the PCR product was digested using BamHI. The digested PCR products were ligated to the BamHI-restricted vector pSG5 (Stratagene). Plasmids with the correct orientation of the insert were purified using the Qiagen Plasmid Mini Kit. Culture dishes with 80% confluent CE cells were incubated with 1 μg of plasmid DNA using 10 μl of Lipofectamine reagent for 4 h at 38°C. Thereafter, the supernatant was exchanged for fresh medium containing 5% fetal calf serum. After 2 days of incubation at 38°C, protein expression was analyzed by immunofluorescence.

Analysis of proteins.

Expression of the recombinant proteins was analyzed by immunoblotting and immunofluorescence as described previously (12, 39). The polyclonal antibody αAPV, directed against APV structural proteins and raised in rabbits by using purified APV particles (39); the polyclonal antibody α1a, directed against APV VP4 (12); and the monoclonal antibody 3G10G5, directed against APV VP1 (4) were used. For immunoblotting, the antibody αAPV was used at a 1:1,000 dilution. For immunofluorescence, cells grown on glass coverslips were fixed for 30 min using ice-cold acetone-methanol. Thereafter, the antibody α1a, diluted 1:200 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), was added, or the monoclonal antibody 3G10G5 was used at a 1:50 dilution. After 1 h at 37°C, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled secondary antibodies (Sigma) were added at a 1:100 dilution. Tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-labeled secondary antibodies (Sigma) were used in double-labeling experiments. The percentage of stained cells was estimated by counting 200 cells with an IX70 fluorescence microscope (Olympus) with UV light at 470- to 490-nm wavelength for the detection of FITC and at 510- to 550-nm wavelength for TRITC detection.

Density gradient centrifugation.

To analyze VLP formation in infected CE cells by density gradient centrifugation, the cells were sonicated on ice in the presence of 1,1,2-trichlortrifluorethane. Cellular debris was removed by low-speed centrifugation, and the supernatant was applied to preformed density gradients. In two series of experiments, different types of density gradients were used. First, a two-step cesium chloride density gradient (densities, 1.3 and 1.4 g/ml) was used as described previously (22). After centrifugation, the visible protein band was collected and subjected to a second purification in a similar gradient but in a smaller volume. Thereafter, the protein band was collected again and centrifuged for 2 h at 40,000 rpm in an SW41 rotor (Beckman). The pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of PBS and analyzed by electron microscopy.

In the second set of experiments, continuous gradients of Nycodenz (Sigma) were preformed. To this end, 40, 30, 20, and 10% solutions of Nycodenz in PBS (2.5-ml volume each) were carefully overlaid and subsequently frozen at −20°C. The cellular lysate, prepared as described above, was added to the frozen gradient and thawed at 37°C. After centrifugation (25,000 rpm; 4 h; Beckman SW28 rotor [UL-70K]), 10 fractions (1 ml each) were collected from the bottom of the tube, and the refractive indexes were determined at 20°C using a refractometer (32-G110e; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Fractions with refractive indexes between 1.3950 (corresponding to 1.20 g/ml [27]) and 1.4100 (corresponding to 1.25 g/ml) were pooled, as the presence of APV particles in fractions with these densities had been determined in previous experiments. The fractions were diluted in PBS and centrifuged for 2 h at 40,000 rpm in an SW41 rotor. The pellet was subsequently analyzed by immunoblotting and electron microscopy.

Electron microscopy.

Protein preparations collected after cesium chloride density gradient purification were adsorbed to carbon-coated grids for 5 min. After two washings with doubly distilled water, negative staining was performed using a 2% aqueous uranyl acetate solution. Specimens were subsequently examined with a Zeiss EM 900 electron microscope.

Amino acid sequence analysis.

The VP1 sequences of 10 polyomaviruses with the following accession numbers were derived from the GenBank database: M74843 (APV), AF038616 (SV40), Z19536 (BKPyV), AF015537 (JCPyV), K02737 (MPyV), M55904 (mouse pneumotropic polyomavirus [MPtV]), P03092, (hamster polyomavirus [HaPyV]), M74843 (bovine polyomavirus [BPyV]), M14494 (β-lymphotropic polyomavirus [LPyV]), and AY140894 (goose hemorrhagic polyomavirus). Sequence alignment was done with the MegAlign module of the Lasergene system software (DNASTAR) using the Clustal W method and the residue identity weight table.

RESULTS

Expression of APV proteins in CE cells using recombinant influenza viruses.

Influenza virus transfer plasmids were constructed for the generation of recombinant influenza viruses expressing the APV structural proteins VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4, as well as for the nonstructural protein VP4Δ. Cotransfection of 293T cells with the respective transfer plasmid, along with the booster plasmids, was followed by infection with influenza helper viruses, and recombinant influenza viruses were released into the tissue culture supernatants. The supernatants were used for the infection of CE cell cultures, which were analyzed 24 h later by immunoblotting (Fig. 2). Using the antibody αAPV, intensively stained protein bands were observed in the case of cells infected with VP1-, VP3-, and VP4-expressing recombinant influenza viruses at positions corresponding to those of the proteins detected in APV-infected CE cells. (VP3 and VP4 were not distinctly separated under the gel conditions used; some additional minor bands are considered to represent degradation products.) Faint bands at a position corresponding to VP2 were visible in the case of infection with the VP2-expressing influenza virus, as well as in the APV-infected cells. A faint band was also observed in the case of infection with the VP4Δ-expressing influenza virus. At ∼33 kDa, the apparent molecular mass of this protein was slightly higher than that recently determined (29 kDa [19]). As in the cases of VP2 and VP4Δ the expression levels were low and near the detection limit of immunoblotting, both proteins were excluded from further experiments.

FIG. 2.

Demonstration of APV late gene products in CE cells infected with recombinant influenza viruses expressing VP1, VP2, VP3, VP4, or VP4Δ. At 24 h after infection, the cells were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-12.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by immunoblotting using polyclonal antibody directed against APV particles. M, molecular mass markers, indicated on the left; APV, CE cells 4 days after infection with APV. The positions of the APV structural proteins are indicated. As gels with 12.5% acrylamide were used, VP3 and VP4 were not distinctly separated.

Subcellular localization of APV structural proteins.

Immunofluorescence microscopy was used to determine the subcellular localization of the recombinant proteins in CE cells infected with the recombinant influenza viruses (Fig. 3, top row). At 8 h after infection, immunofluorescence was observed in ∼40% of the cells with APV-specific antibodies, indicating the number of cells infected with the recombinant influenza viruses. Using the monoclonal antibody 3G10G5, directed against APV VP1, the protein was shown to be present as compact granular structures within the cytoplasm of cells infected with VP1-expressing influenza viruses. This is in marked contrast to the predominant intranuclear localization of the protein in APV-infected cells (Fig. 3, bottom row). Using the polyclonal antibody α1a, directed against APV VP4, diffuse staining of the cytoplasm was observed in the cells infected with VP4-expressing influenza viruses. Again, this is in contrast to the intranuclear staining of VP4 in APV-infected cells. Due to the intensive background staining in immunofluorescence (data not shown) produced by the polyclonal antibody αAPV, used in immunoblotting, and the lack of specific antibodies, a detailed analysis of the subcellular localization of VP3 was not possible.

FIG. 3.

Subcellular localization of VP1 and VP4 in CE cells, demonstrated by indirect immunofluorescence using a monoclonal antibody directed against VP1 (left) or a polyclonal antibody directed against VP4 (right). Top row, analysis 8 h after infection with VP1 (VP1 influenza)- or VP4 (VP4 influenza)-expressing influenza viruses; middle row, analysis 2 days after transfection with plasmids expressing VP1 (VP1 transfection) or VP4 (VP4 transfection); bottom row, analysis 3 days after infection with APV (APV infection).

To exclude a possible influence of the recombinant influenza viruses on the subcellular localization of the APV proteins, transfection experiments with VP1- and VP4-expressing plasmids were performed. In both cases, the localization of the recombinant proteins in the cytoplasm was confirmed (Fig. 3, middle row).

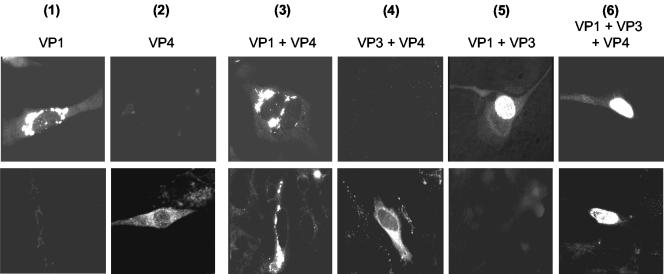

Subcellular localization of coexpressed APV structural proteins.

CE cells were coinfected with recombinant influenza viruses expressing individual APV proteins. At 8 h after infection, the localization of the proteins was determined by indirect immunofluorescence using the monoclonal antibody 3G10G5 in the case of VP1 (Fig. 4, upper row) and the polyclonal antibody α1a in the case of VP4 (Fig. 4, lower row). After coinfection of the cells with VP1- and VP4-expressing influenza viruses, VP1 was again observed as compact granular structures located in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4, lane 3). About 30% of the infected cells showed diffuse staining of the cytoplasm with the antibody directed against VP4. However, in ∼5% of the cells, most likely representing double-infected cells, VP4 formed compact granular structures similar to those observed after VP1 staining (Fig. 4, lane 3). In contrast, coinfection of cells with VP4- and VP3-expressing influenza viruses did not alter the diffuse staining of VP4 in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4, lane 4).

FIG. 4.

Subcellular localization of VP1 and VP4 after expression of VP1 (lane 1) or VP4 (lane 2) or after coexpression of different combinations of VP1, VP3, and VP4 (lanes 3 to 6) in CE cells. The cells were analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence 8 h after (co)infection with VP1-, VP3-, or VP4-expressing influenza virus using a monoclonal antibody directed against VP1 (VP1-specific staining; upper row) or a rabbit serum directed against VP4 (VP4-specific staining; lower row).

About 30% of the cells coinfected with VP1- and VP3-expressing influenza viruses showed compact granular structures in the cytoplasm with the VP1-specific monoclonal antibody. However, ∼7% of the cells showed strong intranuclear fluorescence (Fig. 4, lane 5); they were considered to be double infected. When the cells were simultaneously infected with VP1-, VP3-, and VP4-expressing influenza viruses, again ∼30% showed the intracytoplasmic VP1-specific staining described previously. However, in ∼5% of the cells, VP1-specific fluorescence was also observed in the nucleus (Fig. 4, lane 6). In this case, VP4-specific staining produced diffuse fluorescence of the cytoplasm in ∼30% of the cells (single infected), compact granular structures in the cytoplasm of ∼4% of the cells (double infected; VP4 and VP1 expression), and intranuclear fluorescence in ∼2% of the cells (triple infected [Fig. 4, lane 6]).

To demonstrate colocalization of VP1 and VP4, cells were coinfected with the appropriate influenza viruses and a double-labeling immunofluorescence analysis was performed 8 h after infection (Fig. 5). In these experiments, VP1 was detected with the monoclonal antibody 3G10G5, together with FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies, and VP4 was detected using the polyclonal antibody α1a, together with TRITC-labeled secondary antibodies. As expected, both antibodies demonstrated the presence of compact granular structures located in the cytoplasm of ∼5% of the cells (Fig. 5, upper row). In the merged picture, yellow staining indicated the colocalization of both proteins. In cells coinfected with VP1-, VP3-, and VP4-expressing influenza viruses, however, intensive yellow intranuclear staining of dot-like structures was observed in the merged picture in ∼2% of the cells (Fig. 5, lower row).

FIG. 5.

Demonstration of the colocalization of VP1 and VP4 using double-labeling immunofluorescence of CE cells coinfected with recombinant influenza viruses. Immunofluorescence was performed 8 h after infection using the monoclonal antibody 3G10G5 and anti-mouse-FITC conjugate for VP1-specific staining and the polyclonal antibody α1a directed against VP4 in combination with anti-rabbit-TRITC conjugate (VP4-specific staining). Upper row, coinfection with VP1- and VP4-expressing influenza viruses; lower row, coinfection with VP1-, VP3-, and VP4-expressing influenza viruses.

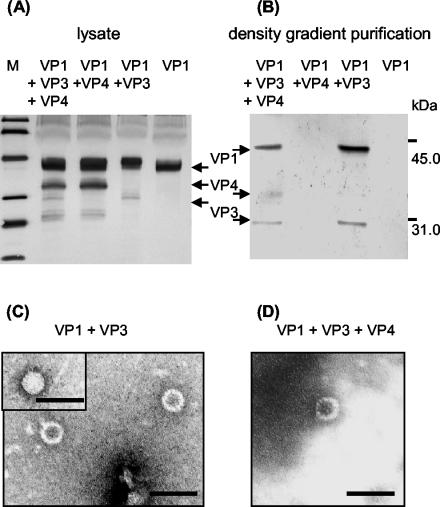

Analysis of VLP formation.

CE cells were infected with VP1-expressing influenza viruses or coinfected with a combination of influenza viruses expressing VP1 and VP3, VP1 and VP4, or VP1, VP3, and VP4. Immunoblotting using the polyclonal antibody αAPV revealed the presence of the expected APV-specific proteins (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Analysis of APV VLP formation by density gradient centrifugation, immunoblotting, and electron microscopy. CE cells were sonicated 24 h after infection with different combinations of VP1-, VP3-, and VP4-expressing influenza viruses. (A) The presence of the proteins in the lysate was demonstrated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by immunoblotting using a polyclonal antibody directed against APV particles. (B) Lysates were subjected to Nycodenz density gradient centrifugation, and fractions with buoyant densities corresponding to that of APV particles were collected, subjected to centrifugation, and subsequently analyzed by immunoblotting as described above. The positions of the APV structural proteins are indicated. M, molecular mass markers (from top to bottom: 97.4, 67.2, 45.0, 31.0, and 21.5 kDa). (C and D) Electron microscopic demonstration (uranyl acetate staining) of VLP purified by Nycodenz density gradient centrifugation from CE cell lysates coinfected with VP1- and VP3-expressing influenza viruses (C) or with VP1-, VP3-, and VP4-expressing influenza viruses (D). The inset in panel C shows a full particle. Bars, 100 nm.

When lysates of five tissue culture dishes (diameter, 135 mm) were pooled, treated with 1,1,2-trichlortrifluorethane, and subjected to cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation, no distinct protein bands were visible at the end of the centrifugation (not shown). Further analysis was performed with the same number of infected tissue culture dishes using continuous Nycodenz density gradients. To increase the concentration of proteins with buoyant densities corresponding to those of APV particles, fractions with refractive indexes of 1.3950 to 1.4100 were combined, subjected to sedimentation, and subsequently analyzed by immunoblotting with the polyclonal antibody αAPV. By this method, APV-specific proteins were observed only when the cells had been coinfected with VP1- and VP3-expressing influenza viruses or in the case of a triple infection with viruses expressing VP1, VP3, and VP4 (Fig. 6B). To demonstrate VLP formation in these cases, a higher number of infected cells (20 tissue culture dishes; diameter, 135 mm) were treated as described above and submitted to centrifugation in Nycodenz or cesium chloride density gradients. Electron microscopy revealed the presence of isolated VLP with diameters of ∼45 nm in each case (the Nycodenz gradients are shown in Fig. 6C and D). Empty and “full” particles (Fig. 6C) were found at the same rates when preparations containing VP1 and VP3 were compared with those containing VP1, VP3, and VP4.

Mutant APV VP1 with the NLS of SV40 migrates to the nucleus and forms VLP.

To investigate the significance of the nuclear localization of VP1 for VLP formation, recombinant influenza viruses expressing a mutant APV VP1 with the N-terminal amino acids of the bipartite SV40 VP1 NLS were generated. The alignment of the N-terminal VP1 sequences of 10 polyomaviruses revealed marked differences in amino acid composition (Fig. 7). The basic KRK motif, previously shown to mediate nuclear transport of SV40 VP1 (8), is missing in the VP1 sequences of five polyomaviruses, including APV. Using site-directed mutagenesis, a mutant APV VP1 with this motif was generated and designated VP1-NLSSV40, and CE cells were infected with recombinant influenza virus expressing this protein. Immunofluorescence with the monoclonal antibody 3G10G5 revealed that VP1-NLSSV40 was localized mainly within the nucleus (Fig. 8A). When 1,1,2-trichlortrifluorethane-treated cells were subjected to cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation, a distinct protein band formed at a buoyant density of 1.31 g/ml. Electron microscopy of negatively stained preparations revealed the presence of VLP with a mean diameter of ∼45 nm (Fig. 8B). The VLP varied in shape and size, and empty as well as “full” particles were observed.

FIG. 7.

Alignment of N-terminal VP1 amino acid sequences of 10 polyomaviruses. The abbreviations of the designations of polyomaviruses are according to van Regenmortel et al. (41). GHPV, goose hemorrhagic polyomavirus according to Johne and Müller (13). Basic amino acids potentially serving as an NLS are in boldface.

FIG. 8.

Analysis of the subcellular localization of VP1-NLSSV40 and VLP formation. (A) Immunofluorescent staining of CE cells 8 h after infection with VP1- or VP1-NLSSV40-expressing influenza viruses using a monoclonal antibody against VP1. The amino acid sequences of the N termini of both proteins are indicated (exchanged residues are italicized). (B) (Left) Electron microscopic demonstration (uranyl acetate staining) of VLP purified from CE cell lysates infected with VP1-NLSSV40-expressing influenza viruses and concentrated by CsCl density gradient centrifugation. (Right) APV particles. Different types of particles, either empty (solid arrows) or full (open arrows), as well as a smaller particle (shaded arrow), are indicated. Bars, 100 nm.

DISCUSSION

The capsid structures and assemblies of several mammalian polyomaviruses have been intensively studied using virion- as well as VLP-based approaches. Compared to mammalian polyomaviruses, however, available data indicate marked differences in the structure and assembly of the APV capsid due to (i) the incorporation of a fourth structural protein, VP4, in addition to VP1, VP2, and VP3 (12) and (ii) the missing or inefficient formation of VLP following VP1 expression in insect cells (1) or yeast (35), respectively. In order to investigate the requirements for APV capsid assembly, the APV structural proteins were expressed in CE cells permissive for APV replication, the proteins were localized within the cell, and the conditions for VLP formation were analyzed.

The RNA polymerase I-based recombinant influenza virus expression system was chosen due to the documented high level of gene expression in a variety of cell types derived from various animal species (24, 40), including avian cells (19, 20). Using this system, we were able to express all of the APV structural proteins in CE cells, as demonstrated by immunoblotting. However, expression rates differed considerably, obviously depending on the natures of the individual proteins. Remarkably, the amount of each protein correlated with the relative abundance of the protein in APV-infected cells, e.g., VP1 showed the largest amount and VP2 the smallest. As transcription and processing of RNA are performed in different ways in APV and influenza viruses, these results suggest that the expression rates of the APV structural proteins are regulated at the level of mRNA translation or after translation.

Coinfection of CE cells with influenza viruses expressing different structural proteins revealed that VP1 was not transported alone to the nucleus but in a complex with VP3. This is in accordance with results obtained after coexpression of these proteins in insect cells using a baculovirus expression system (1) and could be explained by the use of an NLS common to VP2 and VP3 (28). The mechanisms of nuclear transport of structural proteins seem to be remarkably variable among the polyomaviruses. For MPyV, it has been shown that, by separate expression of each protein, VP1 localizes within the nucleus, whereas VP2 is associated with cytoplasmic membrane structures and VP3 localizes within the cytoplasm (3). After coexpression, all of the proteins are detected within the nucleus. All of the structural proteins of SV40, however, show nuclear localization after their individual expression, as well as after coexpression (33). The bipartite NLS of SV40 VP1 has been mapped at the N terminus of the protein (amino acids [aa] 5 to 7 and 16 to 19), and replacement of the amino acid sequence KRK (aa 5 to 7) by KGK abolished nuclear localization (8). VP1 of APV carries a KGK sequence at the corresponding position (Fig. 7); the replacement of the N-terminal amino acids of APV VP1 with the corresponding amino acids of SV40 VP1 proved to be sufficient for nuclear transport.

Nuclear localization of VP1 correlated with the formation of VLP. This is suggestive of an involvement of cellular factors, which are active either within the nucleus or during the transport of VP1 to the nucleus, in APV capsid assembly. It has been shown for MPyV (32), as well as APV (30), that the concentration of calcium ions is crucial for the formation of VLP by VP1 expressed in Escherichia coli. Therefore, a difference between the calcium ion concentrations of the cytoplasm and the nucleus could be one possible factor in capsid formation. Recently, the significance of disulfide bonds between VP1 pentamers for MPyV (36) and SV40 particle assembly (9, 15, 17) has been shown, and they may also play a role in APV. Also, specific interactions of VP1 with chaperones (2) and importins (23) could contribute to capsid assembly. As VLP formation in insect cells could not be demonstrated even after coexpression of VP1, VP2, and VP3 of APV (1), an interaction with such cell-type-specific factors, which might be missing in insect cells, has to be considered.

The distinct function of VP4 within the APV capsid remains unclear. Coexpression of VP4 with VP1 did not induce VLP assembly. Also, a function in nuclear trafficking of other structural proteins can be excluded, as a previously proposed NLS between aa 70 and 77 of VP4 (12) proved not to be functional, since only intracytoplasmic localization of the protein was observed. It is evident from the experiments described here that VP4 colocalizes with VP1 and that its nuclear transport is facilitated by a complex containing VP1, VP3, and VP4. Interactions between VP4 and VP1 have been also demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation assays using proteins expressed in insect cells (12). As VP4 has been shown to have DNA binding activity (12), a possible role in packaging of viral DNA into the capsid should be considered. Taken together, the results support a model of APV capsid assembly in which a complex of the structural proteins VP1, VP3 (or VP2), and VP4 is formed within the cytoplasm and is transported to the nucleus using the NLS of VP3 (or VP2). Thereafter, capsid formation is induced within the nuclear environment and viral DNA is packaged, presumably facilitated by VP4.

VLP are known to be excellent antigens, inducing both a cellular and a humoral immune response without requiring any adjuvant (5, 37, 42). The recombinant influenza viruses expressing VP1-NLSSV40 could be used for the production of VLP in CE cells or, presumably, in embryonated chicken eggs. After removing the influenza viruses by treatment with organic solvents, these VLP should be considered an efficient and safe vaccine against the severe disease caused by APV in many species of birds.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Hobom for providing the influenza virus expression system and R. A. Consigli for providing the monoclonal antibody against APV VP1.

REFERENCES

- 1.An, K., S. A. Smiley, E. T. Gillock, W. M. Reeves, and R. A. Consigli. 1999. Avian polyomavirus major capsid protein VP1 interacts with the minor capsid proteins and is transported into the cell nucleus but does not assemble into capsid-like particles when expressed in the baculovirus system. Virus Res. 64:173-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cripe, T. P., S. E. Delos, P. A. Estes, and R. L. Garcea. 1995. In vivo and in vitro association of hsc70 with polyomavirus capsid proteins. J. Virol. 69:7807-7813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delos, S. E., L. Montross, R. B. Moreland, and R. L. Garcea. 1993. Expression of the polyomavirus VP2 and VP3 proteins in insect cells: coexpression with the major capsid protein VP1 alters VP2/VP3 subcellular localization. Virology 194:393-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fattaey, A., L. Lenz, and R. A. Consigli. 1992. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies to budgerigar fledgling disease virus major capsid protein VP1. Avian Dis. 36:543-553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gedvilaite, A., C. Frommel, K. Sasnauskas, B. Micheel, M. Ozel, O. Behrsing, J. Staniulis, B. Jandrig, S. Scherneck, and R. Ulrich. 2000. Formation of immunogenic virus-like particles by inserting epitopes into surface-exposed regions of hamster polyomavirus major capsid protein. Virology 273:21-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldmann, C., H. Petry, S. Frye, O. Ast, S. Ebitsch, K. D. Jentsch, F. J. Kaup, F. Weber, C. Trebst, T. Nisslein, G. Hunsmann, T. Weber, and W. Luke. 1999. Molecular cloning and expression of major structural protein VP1 of the human polyomavirus JC virus: formation of virus-like particles useful for immunological and therapeutic studies. J. Virol. 73:4465-4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon-Shaag, A., O. Ben-Nun-Shaul, V. Roitman, Y. Yosef, and A. Oppenheim. 2002. Cellular transcription factor Sp1 recruits simian virus 40 capsid proteins to the viral packaging signal, ses. J. Virol. 76:5915-5924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishii, N., N. Minami, E. Y. Chen, A. L. Medina, M. M. Chico, and H. Kasamatsu. 1996. Analysis of a nuclear localization signal of simian virus 40 major capsid protein Vp1. J. Virol. 70:1317-1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jao, C. C., M. K. Weidman, A. R. Perez, and E. Gharakhanian. 1999. Cys9, Cys104 and Cys207 of simian virus 40 Vp1 are essential for inter-pentamer disulfide-linkage and stabilization in cell-free lysates. J. Gen. Virol. 80:2481-2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johne, R., A. Jungmann, and H. Müller. 2000. Agnoprotein 1a and agnoprotein 1b of avian polyomavirus are apoptotic inducers. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1183-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johne, R., and H. Müller. 1998. Avian polymavirus in wild birds: genome analysis of isolates from Falconiformes and Psittaciformes. Arch. Virol. 143:1501-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johne, R., and H. Müller. 2001. Avian polyomavirus agnoprotein 1a is incorporated into the virus particle as a fourth structural protein, VP4. J. Gen. Virol. 82:909-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johne, R., and H. Müller. 2003. The genome of goose hemorrhagic polyomavirus, a new member of the proposed subgenus Avipolyomavirus. Virology 308:291-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krautwald, M. E., H. Müller, and E. F. Kaleta. 1989. Polyomavirus infection in budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus): clinical and aetiological studies. J. Vet. Med. B 36:459-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, P. P., A. Nakanishi, S. W. Clark, and H. Kasamatsu. 2002. Formation of transitory intrachain and interchain disulfide bonds accompanies the folding and oligomerization of simian virus 40 Vp1 in the cytoplasm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1353-1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, P. P., A. Nakanishi, D. Shum, P. C. Sun, A. M. Salazar, C. F. Fernandez, S. W. Chan, and H. Kasamatsu. 2001. Simian virus 40 Vp1 DNA-binding domain is functionally separable from the overlapping nuclear localization signal and is required for effective virion formation and full viability. J. Virol. 75:7321-7329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, P. P., A. Nakanishi, M. A. Tran, A. M. Salazar, R. C. Liddington, and H. Kasamatsu. 2000. Role of simian virus 40 Vp1 cysteines in virion infectivity. J. Virol. 74:11388-11393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liddington, R. C., Y. Yan, J. Moulai, R. Sahli, T. L. Benjamin, and S. C. Harrison. 1991. Structure of simian virus 40 at 3.8-A resolution. Nature 354:278-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, Q., M. Hintz, J. Li, M. Linder, R. Geyer, and G. Hobom. 2000. Recombinant expression and modification analysis of protein agno-1b encoded by avian polyomavirus BFDV. Arch. Virol. 145:1211-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, Q., and G. Hobom. 2000. Agnoprotein-1a of avian polyomavirus budgerigar fledgling disease virus: identification of phosphorylation sites and functional importance in the virus life-cycle. J. Gen. Virol. 81:359-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montross, L., S. Watkins, R. B. Moreland, H. Mamon, D. L. Caspar, and R. L. Garcea. 1991. Nuclear assembly of polyomavirus capsids in insect cells expressing the major capsid protein VP1. J. Virol. 65:4991-4998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller, H., and R. Nitschke. 1986. A polyoma-like virus associated with an acute disease of fledgling budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 175:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakanishi, A., D. Shum, H. Morioka, E. Otsuka, and H. Kasamatsu. 2002. Interaction of the Vp3 nuclear localization signal with the importin alpha 2/beta heterodimer directs nuclear entry of infecting simian virus 40. J. Virol. 76:9368-9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neumann, G., A. Zobel, and G. Hobom. 1994. RNA polymerase I-mediated expression of influenza viral RNA molecules. Virology 202:477-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neumann, G., T. Watanabe, H. Ito, S. Watanabe, H. Goto, P. Gao, M. Hughes, D. R. Perez, R. Donis, E. Hoffmann, G. Hobom, and Y. Kawaoka. 1999. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9345-9350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pawlita, M., M. Müller, M. Oppenländer, H. Zentgraf, and M. Herrmann. 1996. DNA encapsidation by virus-like particles assembled in insect cells from the major capsid protein VP1 of B-lymphotropic papovavirus. J. Virol. 70:7517-7526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rickwood, D., T. Ford, and J. Graham. 1982. Nycodenz: a new nonionic iodinated gradient medium. Anal. Biochem. 123:23-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rihs, H. P., R. Peters, and G. Hobom. 1991. Nuclear localization of budgerigar fledgling disease virus capsid protein VP2 is conferred by residues 308-317. FEBS Lett. 291:6-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritchie, B. W., F. D. Niagro, and K. S. Latimer. 1991. Polyomavirus infections in adult psittacine birds. J. Assoc. Avian Vet. 5:202-206. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodgers, R. E., D. Chang, X. Cai, and R. A. Consigli. 1994. Purification of recombinant budgerigar fledgling disease virus VP1 capsid protein and its ability for in vitro capsid assembly. J. Virol. 68:3386-3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rott, O., M. Kröger, H. Müller, and G. Hobom. 1988. The genome of budgerigar fledgling disease virus, an avian polyomavirus. Virology 165:74-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salunke, D. M., D. L. Caspar, and R. L. Garcea. 1986. Self-assembly of purified polyomavirus capsid protein VP1. Cell 46:895-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandalon, Z., and A. Oppenheim. 1997. Self-assembly and protein-protein interactions between the SV40 capsid proteins produced in insect cells. Virology 237:414-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandmeier, H., H. Gerlach, R. Johne, and H. Müller. 1999. Polyomavirusinfektionen bei exotischen Vögeln in der Schweiz. Schweiz Arch. Tierheilk. 141:223-229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sasnauskas, K., A. Bulavaite, A. Hale, L. Jin, W. A. Knowles, A. Gedvilaite, A. Dargeviciute, D. Bartkeviciute, A. Zvirbliene, J. Staniulis, D. W. Brown, and R. Ulrich. 2002. Generation of recombinant virus-like particles of human and non-human polyomaviruses in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Intervirology 45:308-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt, U., R. Rudolph, and G. Böhm. 2000. Mechanism of assembly of recombinant murine polyomavirus-like particles. J. Virol. 74:1658-1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sedlik, C., G. Dadaglio, M. F. Saron, E. Deriaud, M. Rojas, S. I. Casal, and C. Leclerc. 2000. In vivo induction of a high-avidity, high-frequency cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response is associated with antiviral protective immunity. J. Virol. 74:5769-5775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stehle, T., Y. Yan, T. L. Benjamin, and S. C. Harrison. 1994. Structure of murine polyomavirus complexed with an oligosaccharide receptor fragment. Nature 369:160-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stoll, R., D. Luo, B. Kouwenhoven, G. Hobom, and H. Müller. 1993. Molecular and biological characteristics of avian polyomaviruses: isolates from different species of birds indicate that avian polyomaviruses form a distinct subgenus within the polyomavirus genus. J. Gen. Virol. 74:229-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strobel, I., M. Krumbholz, A. Menke, E. Hoffmann, P. R. Dunbar, A. Bender, G. Hobom, A. Steinkasserer, G. Schuler, and R. Grassmann. 2000. Efficient expression of the tumor-associated antigen MAGE-3 in human dendritic cells, using an avian influenza virus vector. Hum. Gene Ther. 11:2207-2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Regenmortel, M. H. V., C. M. Fauquet, D. H. L. Bishop, E. B. Carstens, M. K. Estes, S. M. Lemon, J. Maniloff, M. A. Mayo, D. J. McGeoch, C. R. Pringle, and R. B. Wickner. 2000. Polyomaviridae, p. 241-246. In Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 42.Zhang, L. F., J. Zhou, S. Chen, L. L. Cai, Q. Y. Bao, F. Y. Zheng, J. Q. Lu, J. Padmanabha, K. Hengst, K. Malcolm, and I. H. Frazer. 2000. HPV6b virus like particles are potent immunogens without adjuvant in man. Vaccine 18:1051-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]