Abstract

Objective

Although the problems associated with insufficient sleep have been thoroughly researched, there has been far less substantiation of problems associated with long sleep. Recent evidence shows that habitual sleep duration greater than 7 hours is associated with increased rates of mortality. This study compared the rates of sleep problems in both long and short sleepers.

Methods

Self-reported sleep complaints (eg, sleep onset latency, awakenings during the night, early morning awakenings, nonrestorative sleep, and daytime sleepiness) of nearly 1000 adults who participated in the National Sleep Foundation’s 2001 Sleep in America Poll, were compared with reported hours of weekday sleep.

Results

There are U-shaped relationships of sleep complaints with reported weekday total sleep time. More specifically, 8-hour sleepers reported less frequent symptoms than long sleepers or 7-hour sleepers.

Conclusions

Thus, long sleepers, as well as short sleepers, report sleep problems, focusing attention to the often-overlooked problems of the long sleeper.

Keywords: sleep, sleep disorders, Long Sleeper Syndrome, Short Sleeper Syndrome, insomnia

INTRODUCTION

The problems associated with insufficient sleep have been well described (1). Lack of sleep has been associated with a wide array of problems in cognitive function (2), affective problems (3), and a host of other functional deficits. Habitual sleep of less than 7 hours was associated with increased mortality in a national sample of over 1 million people (4).

The problems associated with long sleep (over 8 hours) have been addressed to a far lesser extent. Early work showed that this group experienced increased psychopathologic symptoms, including increased propensity for worrying and ruminating (5, 6). Newer findings suggest that additional problems may also be associated with long sleep. For example, people who increased their sleep length reported increased midsleep awakenings and prolonged sleep onset latency (7). Also, more than 7 hours of sleep is associated with significantly increased mortality hazard (4). This finding has been supported and replicated by recent studies (8–10).

Rates of insomnia complaints and BMI (kg/m2) follow a U-shaped distribution across hours of total sleep time (4, 11). Additionally, use of sleep aids, falling asleep during activities, daytime napping, trouble initiating sleep, waking during the night, early awakening, trouble getting back to sleep, snoring, obesity, and depression all followed a U-shaped distribution across hours of sleep in postmenopausal women (11).

Although the risk of mortality increases with sleep length beyond 7 hours, the possible mechanisms of action are still unclear (4, 9). Additionally, the presentation and characterization of health problems associated with long sleep are not yet clearly established. Perhaps a better understanding of problems associated with long sleep will facilitate understanding of the increased mortality risk.

The present study partially characterized problems associated with long sleep. More specifically, it explored the question of whether long sleepers (more than 8 hours) and short sleepers (less than 7 hours) both reported more sleep complaints than midrange sleepers (7 to 8 hours). The present study evaluated these relationships in the national sample from the Sleep in America Poll conducted by the National Sleep Foundation (12).

METHODS

The Sleep in America poll sample was closely matched to the US Census (12). The sample consisted of 1004 adults (500 men and 504 women) above age 18 (M = 44.28, SD = 16.48, range 18–86). Of the poll sample, 56% were married, and 82% were White/Caucasian (compared with US Census values of 55% and 82%, respectively). The only notable incongruence between the poll data and census data were on the percentage of persons that attended some college, which was 59% in the sample and 45% in the population.

All subjects participated in structured phone interviews. To describe total sleep time (TST), subjects were asked, “On a workday, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one day?” Responses were recorded in whole numbers.

Additionally, all subjects were asked about 5 sleep complaints, “You had difficulty falling asleep,” “You were awake a lot during the night,” “You woke up too early and could not get back to sleep,” “You woke up feeling unrefreshed,” and, “Sleepiness interferes with functioning.” These sleep problems were reported on a Likert scale (1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = A few nights a month, 4 = A few nights a week, 5 = Every night or almost every night). For these analyses, those reporting disturbance “a few nights a month” or less (values 1, 2, and 3) were contrasted with those reporting the symptom “a few nights a week” or more (values 4 and 5). The rationale behind this decision was to discretely compare those subjects who reported a significant disturbance to those subjects who did not.

A 2-way χ-square analysis was performed for each reported problem versus hours of sleep. Due to unreported data, analyses of difficulty falling asleep, wakening during the night, wakening too early, wakening unrefreshed, and daytime sleepiness included 961, 960, 962, 959, and 963 adults, respectively. Additional χ-square analyses were performed to determine whether problems reported by those reporting 8 hours of sleep (N = 276 for difficulty falling asleep, wakening during the night, and wakening unrefreshed, 277 for wakening too early and daytime sleepiness) differed from both those reporting sleep greater than 8 hours (N = 95 for all groups) and those reporting 7 hours of sleep (N = 309 for difficulty falling asleep wakening too early, wakening unrefreshed, and daytime sleepiness, 308 for wakening during the night). Additionally, another 2-way χ-square analysis was used to detect gender differences in the short (4–6 hours), medium (7–8 hours), and long (9–10 hours) sleeper groups and a one-way ANOVA was used to detect BMI differences among these 3 groups.

RESULTS

A correlation matrix of the reported sleep problems is presented in Table 1. All complaints were significantly correlated with each other (p < .0005), though not redundant (sharing at most 26% of variance). When short sleepers (4 –6 hours) were compared with medium sleepers (7–8 hours) and long sleepers (9 –10 hours) in relation to gender, a χ-square analysis demonstrated inequality of groups with respect to gender (X2 = 10.636, p < .01), in that the short, medium, and long sleeper groups were 45%, 51%, and 65% female, respectively. A one-way ANOVA comparing BMI in short, medium, and long sleepers was not significant (F (2960)= 1.842).

TABLE 1.

Spearman’s rho correlations among sleep complaints

| Wakening during the night | Wakening too early | Wakening unrefreshed | Daytime sleepiness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty falling asleep | .450* | .442* | .419* | .251* |

| Wakening during the night | .508* | .452* | .311* | |

| Wakening too early | .343* | .240* | ||

| Wakening unrefreshed | .381* |

p < .0005.

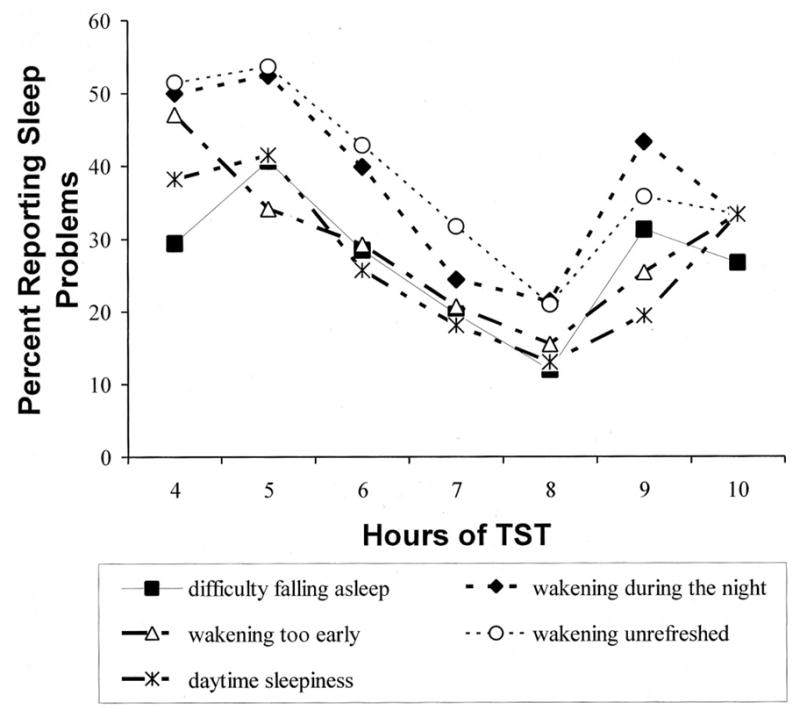

Overall, the respondents reported a mean TST of 6.99 hours (SD = 1.48). TST was significantly related to the frequency of difficulty falling asleep (X2 = 42.562, p < .0005), wakening during the night (X2 = 52.866, p < .0005), wakening too early (X2 = 31.071, p < .0005), wakening unrefreshed (X2 = 46.704, p < .0005), and daytime sleepiness (X2 = 41.330, p < .0005). Sleep complaints were more prevalent for both short and long sleepers than for those who sleep approximately 8 hours. Figure 1 illustrates the U-shaped curve for each of the 5 complaints.

Fig. 1.

From the Sleep in America Poll for 2001, percent of respondents with difficulty falling asleep, wakening during the night, wakening too early, wakening unrefreshed, and daytime sleepiness at least a few nights per week or more, plotted versus reported hours of weekday total sleep time (TST).

Long sleepers reported more problems than 8-hour sleepers with difficulty falling asleep (33.7% vs. 12.0%, X2 = 23.089, p < .0005), wakening during the night (44.2% vs. 21.4%, X2 = 18.598, p < .0005), wakening too early (25.3% vs. 15.5%, X2 = 4.544, p < .05), wakening unrefreshed (35.8% vs. 21.0%, X2 = 8.273, p < .005), and daytime sleepiness (24.2% vs. 13.0%, X2 = 6.666, p < 0.05). Less difference was seen between the 7-hour sleepers and 8-hour sleepers, as the 7-hour sleepers reported significantly more problems only with difficulty falling asleep (64.9% vs. 35.1%, X2 = 6.551, p < .05) and wakening unrefreshed (31.7% vs. 21.0%, X2 = 8.536, p < .005).

DISCUSSION

In a diverse, nationally representative sample, this analysis compared the rates of sleep problems of long and short sleepers to the rates of the same problems among those who sleep approximately 8 hours. Both short and long sleepers reported more sleep problems than midrange sleepers. More specifically, both short and long sleepers reported increased difficulty falling asleep, wakening during the night, wakening too early, wakening unrefreshed, and daytime sleepiness. Weaker differences were found between 7 and 8 hour sleepers. Although it is unclear why long and short sleepers should have similar types of sleep complaints, these data challenge the assumption that more than 7 or 8 hours of sleep is associated with increased health and well-being. The groups were fairly balanced with respect to gender, with the exception that long sleepers consisted of somewhat more females than males. BMI did not differ by group.

A similar U-shaped distribution across hours of TST has been found for mortality (4). Though the mechanism causing this mortality is currently unknown, perhaps the parallel occurrence of sleep problems (as well as other problems) may provide a clue to the pathophysiology. Previous studies (4, 11) have demonstrated the occurrence of a number of problems associated with long sleep, including depression, obesity, and sleep disturbances. The relationship between sleep complaints and depression has been investigated (11), but the degree to which sleep complaints in long sleepers reflect depressive states is not known.

The degree to which problems associated with long sleep are associated with decreased sleep efficiency is not fully understood, nor is the influence of sleep apnea, which may bear its own mortality risk with a possible cardiovascular mode of action (13). Additionally, sleep disturbances (eg, problems falling asleep and early awakenings) have been associated with increased cardiovascular risk of mortality (8). More generally, it is not yet well understood whether people who report long sleep durations have a predominantly subjective abnormality, or whether any physiologic abnormalities are primarily in the quantity or quality of sleep.

There were some important limitations of this study. First, since the data were gathered via phone interviews, their reliability and validity are limited (14). It is also important to remember that the self-report nature of the survey yields a subjective measure of sleep quality and cannot serve as an objective physiological measure. It has not been possible to obtain nationally representative polysomnographic data. Also, due to the data being nonparametric and nonGaussian, it would be difficult statistically to evaluate the relationship between long sleep, sleep problems, and other variables, with multivariate techniques. Another limitation is that there were far more participants who reported sleep of less than 7 or 8 hours than those who reported greater than 8 hours of sleep. Additionally, the sleep problems component of the survey included just 5 questions, which can limit the richness of information collected.

Despite these limitations, this study does contribute to a greater understanding of mortality risk for long sleepers in that it has begun to isolate individual sleep complaints and to suggest that some aspects of sleep must be disturbed. The correlation between long sleeper and more specific sleep complaints should be studied in future research so to elucidate the nature of these sleep problems. These data raise the question whether sleep restriction, a treatment both for insomnia and depression, would have value for problems associated with long sleep (15, 16).

Acknowledgments

The National Sleep Foundation, 1522 K Street, NW, Suite 500, Washington, DC 20005, kindly supplied the raw polling data used for these analyses. This research was supported by NIH AG12364 and AG15763.

Glossary

- TST

total sleep time

References

- 1.Riedel BW, Lichstein KL. Insomnia and daytime functioning. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4:277–98. doi: 10.1053/smrv.1999.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fulda S, Schulz H. Cognitive dysfunction in sleep disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2001;5:423–45. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:131–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartmann E. The Functions of Sleep. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartmann E, Baekeland F, Zwilling GR. Psychological differences between long and short sleepers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972;26:463–68. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750230073014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morin CM, Mimeault V, Gagne A. Nonpharmacological treatment of late-life insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46:103–16. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayas NT, White DP, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE, Malhotra A, Hu FB. A prospective study of sleep duration and coronary heart disease in women. Arch Int Med. 2003;163:205–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojima M, Wakai K, Kawamura T, Tamakoshi A, Aoki R, Lin Y, Nakayama T, Horibe H, Aoki N, Ohno Y. Sleep patterns and total mortality: a 12-year follow-up study in Japan. J Epidemiol. 2000;10:87–93. doi: 10.2188/jea.10.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamakoshi A, Ohno Y, JACC SG. Self-reported sleep duration and depressive symptoms as a predictor of total mortality; Results from the JACC study, Japan. XVIth IEA World Congress of Epidemiology, TP26; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kripke DF, Brunner R, Freeman R, Hendrix SL, Jackson RD, Masaki K, Carter RA. Sleep complaints of postmenaupausal women. Clin J Women’s Health. 2001;5:244–52. doi: 10.1053/cjwh.2001.30491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Sleep Foundation. Make time for sleep: NSF 2001 sleep in America poll. Washington, DC: National Sleep Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mooe T, Franklin KA, Holmstrom K, Rabben T, Wiklund U. Sleep-disordered breathing and coronary artery disease: long-term prognosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1910–13. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2101072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCormick MC, Workman-Daniels K, Brooks-Gunn J, Peckham GJ. When you’re only a phone call away: a comparison of the information in telephone and face-to-face interviews. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1993;14:250–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perlis ML, Youngstedt SD. The diagnosis of primary insomnia and treatment alternatives. Compr Ther. 2000;26:298–306. doi: 10.1007/s12019-000-0033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giedke H, Schwarzler F. Therapeutic use of sleep deprivation in depression. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:361–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]