Abstract

The nucleus accumbens (NAc) receives converging inputs from the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the hippocampus which have competitive interactions in the NAc to influence motivational drive. We have previously shown altered synaptic plasticity in the hippocampal-NAc pathway in the MAM developmental model of schizophrenia in rodents that is dependent on cortical inputs. Thus, because mPFC-hippocampal balance is known to be partially altered in this model, we investigated potential pathological changes in the hippocampal influence over cortex-driven NAc spike activity. Here we show that the reciprocal interaction between the hippocampus and mPFC is absent in MAM animals but is able to be reinstated with the administration of the antipsychotic drug, sulpiride. The lack of interaction between these structures in this model could explain the attentional deficits in schizophrenia patients and shed light onto their inability to focus on a single task.

Keywords: nucleus accumbens, synaptic plasticity, antipsychotic

Introduction

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in primates, which is homologous to the medial PFC (mPFC) in rodents (Ongur and Price, 2000) plays a major role in higher cognitive functions, such as working memory (for review see (Goldman-Rakic, 1990) or set-shifting (Floresco et al., 2006), and deficits in prefrontal cortical activity is believed to be a central component in numerous psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia (Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2001). Moreover, numerous functional studies highlight a major role of the hippocampus (HPC), a region involved in context-dependent processing (Jarrard, 1995), in schizophrenia (Bogerts et al., 1993; Tamminga et al., 1992). Cortical and hippocampal inputs are integrated within the nucleus accumbens (NAc), and disruption of the balance between those two inputs may play a major role in schizophrenia. We have previously shown that the ventral hippocampus and the mPFC exhibit dopamine-dependent reciprocal interactions in the NAc. Thus, high-frequency stimulation (HFS) of the HPC induces a long-lasting depression in the mPFC-evoked activity in the NAc and vice-versa (Goto and Grace, 2005), indicating a competition between the two structures. Moreover, this competition is dopamine-dependent, regulating the balance of information processing within the NAc (Goto and Grace, 2005).

In rodents, prenatal administration of methylazoxymethanol acetate (MAM), an antimitotic agent, leads to anatomic and behavioral disruptions in adults that are comparable to some of the deficits that have been described in schizophrenia patients (Flagstad et al., 2004; Gourevitch et al., 2004; Moore et al., 2006). We have previously shown that hippocampalaccumbens synaptic plasticity is disrupted in the MAM model, and that the deficits observed were dependent on cortical activity (Belujon et al., 2011). Moreover, we demonstrated that those alterations were normalized when the antipsychotic drug sulpiride was administrated systemically (Belujon et al., 2011). In the present study, we used the developmental MAM rodent model of schizophrenia to investigate the influence of the hippocampus on the cortico-accumbens synaptic plasticity and the effect of the antipsychotic drug sulpiride.

Methods

Animals

All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh.

Methylazoxymethanol acetate

MAM- and saline-treated rats were prepared as described previously (Lodge and Grace, 2007; Moore et al., 2006). Briefly, timed pregnant female Sprague-Dawley rats (Hilltop) arrived at gestational day (GD) 15 and were housed individually under a 12 h light/dark cycle. On GD17, dams were injected with the mitotoxin MAM (diluted in saline, 22 mg/kg, i.p.) or with a vehicle, saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.). Male pups were weaned on postnatal day (PD) 21 and housed in groups of 2-3 with littermates.

Extracellular Recordings

In vivo single unit recordings were done in male adult offspring of PD90 or older (MAM: 33 neurons in 33 rats derived from 13 dams; saline: 20 neurons in 20 rats derived from 9 dams). Rats were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg), placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf) and implanted with a catheter in the lateral tail vein to allow for intravenous injections. Extracellular electrodes were pulled from glass micropipettes (WPI) and filled with a 2% Chicago Sky Blue dye solution in 2M NaCl. Microelectrodes were lowered through the NAc (A/P +1.5 mm from bregma; M/L +1.1 mm from midline; D/V -5 to -7.5 mm from the dura). Single-unit signals were amplified and filtered using a Fintronics amplifier (500-5000Hz). Recording were displayed on an oscilloscope (B&K Precision) and transferred via an interface to a computer equipped with LabChart v.7 software. Neuronal activity with a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 or greater was recorded and used for analyses. Only one set of recordings was obtained from each animal.

Stimulation

Single-pulse, low-frequency and high-frequency stimulation were applied via a concentric bipolar stimulating electrode (NEX-100X; Rhodes Medical Instruments) to the fimbria (saline rats: A/P -1.6 mm from bregma; M/L -1.3 mm from the midline; D/V -4.5 mm from the dura; MAM rats: A/P -2 mm from bregma; M/L +1.3 mm from midline; D/V 4.2 mm from dura). A chemotrode (combination of a stimulating electrode and guide cannula, allowing for drug infusion at the stimulation site if necessary) was placed in the mPFC at a 15° angle (saline rats: A/P +2.9 mm from bregma; M/L +1.9 mm from midline; D/V -3 mm from dura (Belujon and Grace, 2008); MAM: A/P +3.2 mm from bregma; M/L +1.3mm from midline; D/V -3.6mm from dura). Coordinates used in MAM-treated rats were adjusted to compensate for the 10 % reduction in brain size (Flagstad et al., 2004).

Only neurons that responded monosynaptically to both mPFC and fimbria stimulations were recorded. The fimbria and the mPFC received alternating single pulse stimuli delivered using a dual output stimulator (S8800; Grass technologies) (frequency 0.5 Hz, intensity 1 mA; pulse-width 0.25 msec). Once a cell was isolated, the current administered to the mPFC was adjusted to evoke an action potential approximately 50% of the time and baseline responses were recorded to have at least 5 min of stable recordings. Spike probabilities were measured by dividing the number of spikes observed by the number of stimuli in 2 min intervals for the baseline period and 5-min intervals after treatment. It should be noted that only a few neurons (5 out of 53) showed more than one spike per mPFC stimulation; the majority responding to the stimulation with a single spike. After recording a stable baseline, high-frequency stimulation (HFS; 20 Hz, 200 pulses, suprathreshold) or low-frequency stimulation (LFS; 5 Hz, 500 pulses, suprathreshold) was administered to the fimbria and mPFC-evoked activity in the NAc was recorded for at least 30 minutes after the stimulation (frequency 0.5 Hz, baseline intensity, 0.25 msec pulse width). For the HFS experiments, 7 saline-treated and 6 MAM-treated dams were used, whereas 6 saline-treated and 5 MAM-treated dams were used for LFS experiments. In experiments in which sulpiride (5mg/kg, i.v.) was injected intravenously, a subsequent evoked activity (10 min) was recorded before tetanization of the fimbria. For those experiments, 8 dams were used for the pre-injection of supiride study and 3 for the pre-injection of saline.

It should be noted that although the majority of the cells were recorded in the shell part of the nucleus accumbens, some were in the core part of the nucleus accumbens. Since no difference was observed between the two parts of the nucleus accumbens, the data have been combined.

Drugs and drug infusions

Following a baseline period, sulpiride (Sigma Aldrich, 5mg/kg) or vehicle (saline, 1ml/kg) were injected intravenously.

Histology

After each experiment, electrode placement was verified by ejection of Chicago Sky Blue dye into the recording site. To verify the stimulation electrode placement, a 10 sec pulse at 200 μA was administered. Rats were euthanized with a lethal dose of chloral hydrate and brains were removed following decapitation. The tissue was fixed in 8% paraformaldehyde for at least 48 h and then transferred to a 25% sucrose solution for cryoprotection. Once saturated, brains were frozen and sliced coronally at 60 μm thick using a cryostat and mounted onto gelatin-chromalum-coated slides. Tissue was stained with combination of neutral red and cresyl violet.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with repeated measures followed by the Holm–Sidak test, with time as the within-subject factor. Multiple comparisons were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA followed by the Holm–Sidak test, with treatment as the between-subject factor and time as the within subject factor.

Results

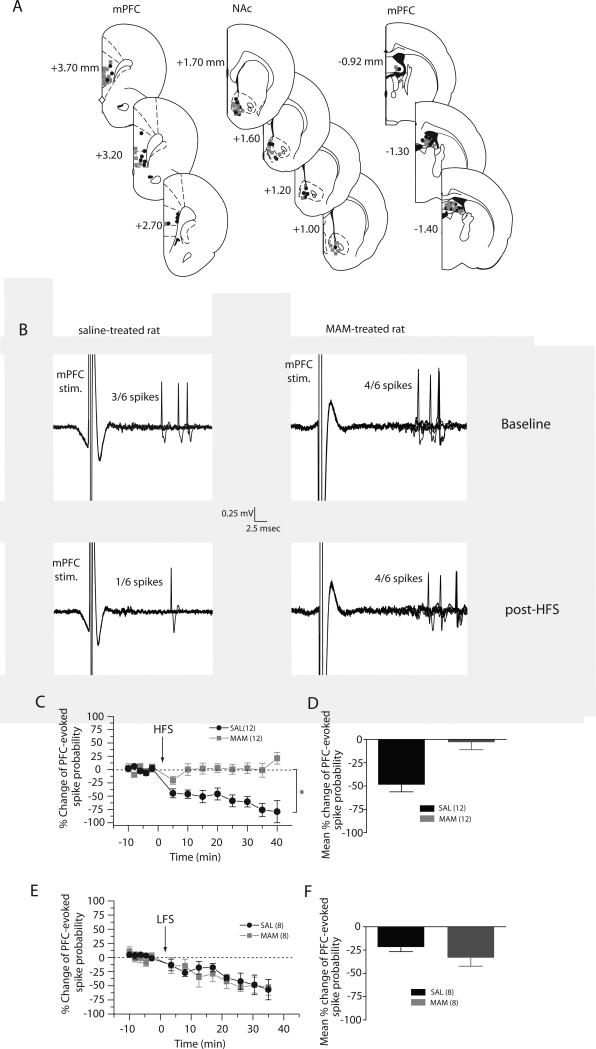

Locations of stimulating and recording electrodes are presented in Figure 1A. The mean baseline spike probability, the latency of fimbria-evoked responses and the current used to obtain 50% spike probability at baseline were not statistically different between MAM- and saline-treated animals (t-test, p=0.1604, p=0.4904 and p=0.0961, respectively; n=20 saline- and n=33 MAM-treated animals).

Figure 1. Disrupted mPFC-evoked hetero-synaptic plasticity induced by fimbria high-frequency stimulation of the fimbria, but not by low-frequency stimulation in MAM-treated rats.

(A) Schematic showing the representative placements of stimulating electrodes in the mPFC (left) and the fimbria (right) and location of recording electrodes in the NAc (middle), shown as coronal sections of the rat brain, taken from Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1996). Numbers to the right indicate millimeters A/P from bregma; approximately 50% of placements are shown. (B) Representative example of extracellular recordings from accumbens neurons evoked by mPFC stimulation before and after tetanization of the fimbria in saline-treated animals (left) and MAM-treated animals (right) (C) Mean percent change (± SEM) in mPFC-evoked spike probability, normalized to the baseline, after HFS to the fimbria in saline-treated (black circles) and MAM-treated (grey squares) animals (*p<0.05; arrow indicates time of stimulation). (D) Mean of the percent change in mPFC-evoked responses (± SEM) following HFS in saline-treated (black bar) and MAM-treated (grey bar) animals. (E) Mean percent change (± SEM) in mPFC-evoked spike probability, normalized to the baseline, after LFS to the fimbria in saline-treated (black circles) and MAM-treated (grey squares) animals (*p<0.05; arrow indicates time of stimulation). (F) Mean of the percent change in mPFC-evoked responses (± SEM) following LFS in saline-treated (black bar) and MAM-treated (grey bar) animals.

Reciprocal interaction between hippocampal and prefrontal cortex are absent in MAM rats

We have previously shown that the hippocampus and the mPFC exert a functionally reciprocal interaction within the NAc (Goto and Grace, 2005). In this study, we confirmed these results in saline animals (Fig 1A). Indeed, tetanization of the fimbria induced a significant and persistent depression (≈ 50 %, > 30 min) of the mPFC-evoked spike probability of accumbens neurons in saline-treated animals (baseline: 0.39 ± 0.08, post-HFS: 0.16 ± 0.09, F=7.989, p<0.05, n=12). However, in MAM animals, tetanization of the fimbria induced an mPFC-evoked spike probability that was highly variable but overall yielded no significant effect. Indeed, the mPFC-evoked spike probability was within a 95% confidence interval (C.I.) of the baseline (baseline: 0.48 ± 0.05; post-tetanus: 0.49 ± 0.08; C.I.: 0.37-0.59; n=12). The difference between the post-HFS mPFC-evoked spike probability was significantly different between MAM- and saline-treated rats (two-way ANOVA, Holm Sidak post-hoc, F=18.841, p<0.05). Therefore, the fimbria tetanization-evoked synaptic plasticity induced in the mPFC-NAc pathway (herein referred to as hetero-synaptic plasticity) is absent in MAM-treated animals.

Low-frequency stimulation-induced synaptic plasticity is not disrupted in MAM-treated rats

While high-frequency stimulation (HFS) usually induces long-lasting enhancement of synaptic efficacy (long-term potentiation, LTP), low-frequency stimulation (LFS) generally mediates long-term depression (LTD). We have previously shown that LFS of the fimbria induced depression in the hippocampus-accumbens pathway, which was not different between MAM-and saline-treated rats (Belujon et al., 2011). Here, we studied the hetero-synaptic plasticity of mPFC afferents to the NAc induced by LFS of the fimbria. As shown in the hippocampus-accumbens pathway (Belujon et al., 2011), LFS to the fimbria induced a long-term depression (≈ 30 %, > 30 min) in the mPFC-NAc pathway in both MAM- and saline-treated rats. Thus, in MAM-treated rats, the spike probability decreased from 0.53 ± 0.10 (baseline) to 0.19 ± 0.04, 30 minutes after LFS (F=3.151, p<0.05, n=8). In saline-treated rats, the spike probability decreased from 0.54 ± 0.03 (baseline) to 0.29 ± 0.10, 30 minutes after LFS to the fimbria (F=5.48, p<0.05, n=8). Moreover, there was no significant difference between the depression of the mPFC-NAc pathway in MAM-treated animals, in comparison with saline-treated animals (two-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak post-hoc, F=0.19, p=0.669).

Therefore, with LFS of the fimbria, mPFC-evoked spiking in the NAc exhibits a similar type of depression in both MAM- and saline-treated rats.

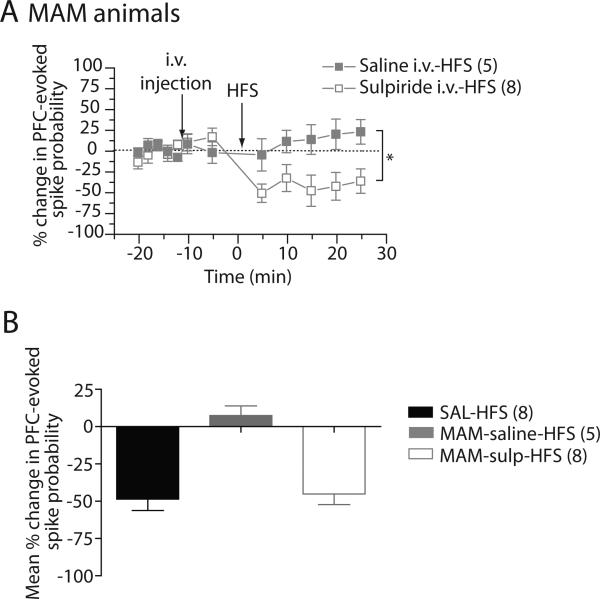

The antipsychotic drug, sulpiride, restores HFS-induced long-term depression in MAM-treated rats

We have previously shown that systemic injection of sulpiride reversed the altered vSub-NAc synaptic plasticity in MAM-treated animals (Belujon et al., 2011). In the present study, we injected sulpiride systemically 10 minutes before HFS of the fimbria and examined whether it affected mPFC driven spiking in the NAc (Fig 2). In MAM-treated rats, blocking D2 receptors with sulpiride did not affect the mPFC-evoked spike probability. The mPFC-evoked spike probability after sulpiride injection was within a 95% confidence interval (C.I.) of the baseline spike probability (baseline: 0.44 ± 0.04; post-sulpiride: 0.41 ± 0.02; C.I.: 0.34-0.54). Injection of saline had no effect on the spike probability as well (baseline: 0.51 ± 0.02; post-saline: 0.53 ± 0.05; C.I.: 0.45-0.57). Tetanization of the fimbria in MAM-treated rats induced a long-lasting depression (≈ 50 %, > 25 min) with a pre-injection of sulpiride. The baseline spike probability was 0.44 ± 0.04 and decreased to 0.25 ± 0.11, 20 minutes after HFS to the fimbria (F=4.951, p<0.05, n=8, Fig 2A). Pre-injection of saline did not induce any change in the mPFC-evoked spiking of the NAc after HFS to the fimbria (baseline: 0.51 ± 0.02, post-saline: 0.53 ± 0.05, post-HFS: 0.55 ± 0.03, F=0.56, p=0.781, n=5, Fig 2A). Moreover, the mPFC-evoked spike probability after sulpiride-HFS was significantly different compared to vehicle injection (two-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak post-hoc, F=6.974, p<0.05). The HFS-induced depression observed after injection of sulpiride in MAM-treated rats is comparable to the HFS-induced long-term depression in saline animals (Fig 2B). Therefore, injection of antipsychotic drug in MAM-treated rats restores the altered mPFC-evoked hetero-synaptic plasticity.

Figure 2. Injection of the D2 antagonist, sulpiride, restores mPFC-NAc LTD in MAM-treated rats.

(A) Mean percent change (±SEM) mPFC-evoked spike probability in NAc neurons, normalized to baseline, following intravenous injection of sulpiride (open squares) or saline (closed squares) and tetanization of the fimbria in MAM-treated animals (*p<0.05; arrows indicate time of injection and stimulation). (B) Mean of the percent change in mPFC-evoked responses (±SEM) after HFS to fimbria in saline animals (black-bars) following an injection of sulpiride (grey bar) or saline (white bar) in MAM-treated animals.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that in the MAM model, the mPFC-evoked hetero-synaptic plasticity induced by tetanus of the fimbria is absent in the NAc and that the long-term depression observed in control rats is restored after injection of the antipsychotic drug sulpiride in the MAM rats.

We found no clear effect of fimbria HFS on the mPFC-NAc pathway of MAM animals. One explanation of this result is that the mPFC of MAM animals is already in a hyper-active state, and thus HFS of the hippocampus cannot induce LTD in the mPFC-NAc pathway. Thus, mPFC neurons were found to fire faster in MAM-treated rats (Lavin et al., 2005) and showed more robust tetanization-induced LTP (Goto and Grace, 2006). Indeed, a loss of parvalbumin-containing interneurons is shown in the PFC (among other structures) in schizophrenia patients (Lewis and Moghaddam, 2006), as well as in the developmental rodent MAM model of schizophrenia (Lodge et al., 2009). This loss could disrupt the effects exerted by multiple inputs to the mPFC, which in the normal rat may in part facilitate the reciprocal interactions between this region and the hippocampus. The site of action of sulpiride in restoring reciprocal interactions between the mPFC and hippocampus is unclear. However, it has been shown that increased dopamine transmission in the NAc tends to shift the mPFC-hippocampal balance in favor of the mPFC (Goto and Grace, 2005). Perhaps in the MAM-treated rat, antipsychotic drug-induced attenuation of the impact of increased NAc DA transmission may serve to restore the balance in the system to allow the interaction to emerge.

Therefore, in the MAM exposed rat, the balance between the mPFC and the hippocampus is disrupted. We have previously postulated that the interaction between the mPFC and the hippocampus is important for gating of attentional states (Grace, 2012; Sesack and Grace, 2010). Thus, the hippocampus subiculum, being a source of context-dependent gating, is proposed to act by keeping an individual focused on a task. Furthermore, the hippocampal input to the NAc is potentiated by D1 stimulation. In contrast, the mPFC is proposed to drive behavioral flexibility, and is down-modulated by D2 stimulation. Therefore, in an individual performing a task resulting in a reward, the increase in dopamine transmission would increase hippocampal inputs to increase attention and performance of a given task, while inhibiting the mPFC from shifting to an alternate task. However, if the action is not rewarded, there is a decrease in the dopamine system (Schultz, 2010), enabling the mPFC to now shift focus. However, if activation of the hippocampus can no longer attenuate the mPFC, a condition could arise in which the subject is caused to increase focused attention on multiple contingencies, due to activation of both the hippocampal-driven task focus and the mPFC-driven flexibility in response. An antipsychotic drug could then serve to normalize this relationship. While admittedly hypothetical, such a relationship could account for disrupted focus and an overwhelming bombardment of stimuli competing for attention (Saks, 2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank Niki MacMurdo and Brandon Bizup for technical assistance.

Statement of interest:

This work was supported by United States Public Health Service Grant MH57440 (A.A.G.).

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Puretech Ventures, Merck, Takeda, Dainippon Sumitomo, Otsuka, Lilly, Roche (A.A.G.)

References

- Belujon P, Grace AA. Critical role of the prefrontal cortex in the regulation of hippocampus-accumbens information flow. J Neurosci. 2008;28(39):9797–9805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2200-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belujon P, Patton MH, Grace AA. Altered hippocampal-accumbens synaptic plasticity in a developmental animal model of schizophrenia. Society for Neuroscience. 2011 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs380. Abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogerts B, Lieberman JA, Ashtari M, Bilder RM, et al. Hippocampus-amygdala volumes and psychopathology in chronic schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;33(4):236–246. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90289-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagstad P, Mork A, Glenthoj BY, van Beek J, et al. Disruption of neurogenesis on gestational day 17 in the rat causes behavioral changes relevant to positive and negative schizophrenia symptoms and alters amphetamine-induced dopamine release in nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(11):2052–2064. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, Magyar O, Ghods-Sharifi S, Vexelman C, et al. Multiple dopamine receptor subtypes in the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat regulate set-shifting. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(2):297–309. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS. Cellular and circuit basis of working memory in prefrontal cortex of nonhuman primates. Prog Brain Res. 1990;85:325–335. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62688-6. discussion 335-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y, Grace AA. Dopaminergic modulation of limbic and cortical drive of nucleus accumbens in goal-directed behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(6):805–812. doi: 10.1038/nn1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourevitch R, Rocher C, Le Pen G, Krebs MO, et al. Working memory deficits in adult rats after prenatal disruption of neurogenesis. Behav Pharmacol. 2004;15(4):287–292. doi: 10.1097/01.fbp.0000135703.48799.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA. Dopamine system dysregulation by the hippocampus: implications for the pathophysiology and treatment of schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(3):1342–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrard LE. What does the hippocampus really do? Behav Brain Res. 1995;71(1-2):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Moghaddam B. Cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia: convergence of gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate alterations. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(10):1372–1376. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.10.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge DJ, Behrens MM, Grace AA. A loss of parvalbumin-containing interneurons is associated with diminished oscillatory activity in an animal model of schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2009;29(8):2344–2354. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5419-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge DJ, Grace AA. Aberrant hippocampal activity underlies the dopamine dysregulation in an animal model of schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2007;27(42):11424–11430. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2847-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Poline JB, Kohn PD, Holt JL, et al. Evidence for abnormal cortical functional connectivity during working memory in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(11):1809–1817. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore H, Jentsch JD, Ghajarnia M, Geyer MA, et al. A neurobehavioral systems analysis of adult rats exposed to methylazoxymethanol acetate on E17: implications for the neuropathology of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(3):253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongur D, Price JL. The organization of networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of rats, monkeys and humans. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10(3):206–219. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saks E. The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness. Hyperion; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Dopamine signals for reward value and risk: basic and recent data. Behav Brain Funct. 2010;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Grace AA. Cortico-Basal Ganglia reward network: microcircuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):27–47. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga CA, Thaker GK, Buchanan R, Kirkpatrick B, et al. Limbic system abnormalities identified in schizophrenia using positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose and neocortical alterations with deficit syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(7):522–530. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820070016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]