Abstract

Propionibacterium acnes is a Gram-positive bacterium that colonizes various niches of the human body, particularly the sebaceous follicles of the skin. Over the last years a role of this common skin bacterium as an opportunistic pathogen has been explored. Persistence of P. acnes in host tissue has been associated with chronic inflammation and disease development, for example, in prostate pathologies. This study investigated the intracellular fate of P. acnes in macrophages after phagocytosis. In a mouse model of P. acnes-induced chronic prostatic inflammation, the bacterium could be detected in prostate-infiltrating macrophages at 2 weeks postinfection. Further studies performed in the human macrophage cell line THP-1 revealed intracellular survival and persistence of P. acnes but no intracellular replication or escape from the host cell. Confocal analyses of phagosome acidification and maturation were performed. Acidification of P. acnes-containing phagosomes was observed at 6 h postinfection but then lost again, indicative of cytosolic escape of P. acnes or intraphagosomal pH neutralization. No colocalization with the lysosomal markers LAMP1 and cathepsin D was observed, implying that the P. acnes-containing phagosome does not fuse with lysosomes. Our findings give first insights into the intracellular fate of P. acnes; its persistency is likely to be important for the development of P. acnes-associated inflammatory diseases.

1. Introduction

The Gram-positive bacterium Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) is ubiquitously present in various niches of the human body, such as the oral cavity, the gastrointestinal tract, and the conjunctiva. It is most prevalent on the human skin, where it colonizes sebaceous follicles of the face and back [1]. Due to its intimate association with sebaceous follicles, it has been studied as the possible etiological agent of the skin disorder acne vulgaris, but clear-cut proof for P. acnes' involvement is still scarce [2–7].

Over the last few years P. acnes' role as an opportunistic pathogen has become more prominent. The bacterium is associated with several inflammatory diseases, such as endophthalmitis, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, sarcoidosis, keratitis, and the SAPHO syndrome and inflammatory conditions linked to surgery or the implantation of foreign devices, such as prosthetic aortic valves, prosthetic hip and shoulder implants [8]. P. acnes is also suspected to cause chronic inflammation in the human prostate that might be associated with the development of prostate cancer. Several studies have reported the detection and isolation of P. acnes from prostate tissue samples of diseased patients [9–13]. In vitro experiments showed that P. acnes can invade the epithelial cell lines A549, HEK293T [14] and the prostate epithelial cell line RWPE1 [9, 15].

Intracellular detection of P. acnes and evidence for inflammation in P. acnes-infected tissues suggest that the intracellular presence of P. acnes supports its long-term persistency in the host, which could result in a chronic inflammatory state. However, persistency is not easily achieved as the host has powerful means to eradicate microbial intruders. An important line of defence is the recruitment of specialized phagocytic cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils. These cells engulf microorganisms into phagosomes, specialized compartments, which undergo concurrent interactions and exchanges with compartments of the endocytic pathway. Thereby the phagosome gradually becomes a highly acidic and oxidizing environment, enriched in hydrolytic enzymes, which finally enables degradation of the microorganism [16–18]. Intracellular pathogens have evolved to subvert or manipulate this mechanism of host defence [19, 20]. Many pathogens master different tricks to either (i) escape the phagosome, such as Listeria and Shigella, (ii) arrest the phagosomal maturation, either at an early state like M. tuberculosis or a late state like Salmonella or (iii) manipulate the host cell to transform the phagosome into a customized pathogen-containing vacuole, such as Legionella, or Chlamydia [19, 20].

For P. acnes not much is known about the fate it undergoes after engulfment by professional phagocytes. In in vivo studies in mice, P. acnes could be detected within phagocytic cells at 6 days after injection [21]. Another study found bacteria in the liver and spleen of mice 15 days after intravenous injection [22]. Webster et al. [23] showed that human polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) and monocytes were unable to degrade P. acnes in vitro. In a sarcoidosis study, P. acnes was identified intracellularly in alveolar macrophages of the lungs and paracortical macrophages of lymph nodes from sarcoidosis patients [24].

Failure of professional phagocytes to eradicate intracellular P. acnes, resulting in bacterial persistence in the host, could lead to chronic tissue inflammation and disease development. In this regard the present study was undertaken to elucidate the intracellular fate of P. acnes after ingestion by macrophages and to investigate the failure of professional phagocytes to degrade the bacteria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Culture

For cell culture infection experiments we used P. acnes strain P6, isolated from a cancerous prostate [9], strain KPA171202 (DSM 16379) [25], strain 266, a pleuropulmonary isolate [26], and P. freudenreichii strain ATCC 6207 (DSM 20271). For mouse prostate inoculations the prostatectomy-derived P. acnes strain PA2 was used [10]. Bacteria were cultured on Brucella agar plates (Sigma Aldrich) for three days at 37°C under anaerobic conditions.

2.2. Animals

All procedures were performed on 8–10-week-old C57BL/6J wildtype mice under the guidelines of the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) and with an approved animal protocol. Mice were housed in a pathogen-free environment, allowed free access to food and water, and were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle. Mice were sacrificed via CO2 asphyxiation 2 weeks after inoculation of P. acnes, and seminal vesicles, urinary bladder, anterior, dorsal/lateral, and ventral prostate lobes were collected along with other reference organs. All tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 48 h before paraffin embedding.

2.3. Transurethral Catheterization and Inoculation of P. acnes

Mice were anaesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and then catheterized via the urethra using lubricated sterile polyethylene catheters (PE-10 tubing, BD Biosciences) 2.5 cm in length. Inoculation of P. acnes strain PA2 into the bladder and prostate was performed with a dose of approximately 107 colony forming units (CFU) in a 20 μL volume.

2.4. Cell Culture

Cells of the human acute monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 (DSMZ, ACC 16) were cultured in RPMI medium with L-glutamine and 25 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (Gibco Invitrogen GmbH) and supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany) and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco Invitrogen GmbH) in 75 cm2 flasks at 37°C and 5% CO2. Phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma Aldrich) was added at a concentration of 1 μM to promote differentiation into macrophages at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 24 h, PMA was removed by one washing step with culture medium. Fresh medium containing interferon-γ (R&B Systems) at a concentration of 150 U/mL was added for another 24 h of incubation to activate macrophages one day before infection. Before P. acnes infection, medium containing penicillin/streptomycin was replaced with one washing step with RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FCS without antibiotics.

2.5. Intracellular Viability Assay

THP-1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 106 cells/well as differentiated and activated cells as described above. Infections were performed at an MOI of 3 at 37°C and 5% CO2. Duplicates were performed for each time point and bacterial strain. Infections were stopped, and extracellular bacteria were killed by 3 h incubation with 300 μg/mL gentamicin (Sigma Aldrich) after 24 h. Cells were lysed by a 10 min treatment with 0.5% saponin (Serva Feinbiochemica GmbH and Co. KG). A dilution series was plated on Brucella agar plates (Sigma Aldrich) to determine viable intracellular bacteria by CFU counting after 5 days of incubation at 37°C under anaerobic conditions. Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA) and GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, USA) were used to analyse and depict results.

2.6. Host Cell Viability

To determine the percentage of dead cells upon P. acnes infection over a time course of 3 days, SYTOX green nucleic acid staining (Invitrogen) was applied. Therefore, THP-1 cells were infected with P. acnes P6 at an MOI of 3 for 24 h, 48 h and 72 h. Noninfected cells were used as a control. Before staining, cells were washed once with PBS to remove extracellular bacteria. SYTOX green nucleic acid staining was added at a concentration of 2 μM, and emission was measured at a range 485–518 nm with a Fluoroskan Ascent reader (Thermo Labsystems). In the next step all cells were killed by addition of 1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) to measure the emission of 100% cell death. Percentage of dead cells was then calculated using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism 5.0.

2.7. Detection of Acidified Cellular Compartments with LysoTracker

The acidotropic dye LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Molecular Probes) was used to detect phagosomal acidification. Prior to infection, LysoTracker was diluted in RPMI 1640 medium at 1 : 10000 and added to THP-1 cells for 2 h. THP-1 cells were infected with P. acnes P6 with an MOI of 5 for 1 h. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and further incubated in the presence of LysoTracker at 1 : 10000. At 2 h, 6 h, and 24 h postinfection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and stained with the anti-P. acnes antibody.

2.8. Immunofluorescence (IF)

THP-1 cells were seeded onto sterilized cover slips (Techno Plastics Products AG) with a diameter of 15 mm in a 12-well plate at 5 × 105 cells/well. Cells were differentiated and activated as described above. Bacteria were grown on Brucella agar plates, and infection was performed at an MOI of 3 or 25 at 37°C and 5% CO2 under aerobic conditions. Infection was stopped by fixation of cells with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Sigma Aldrich) in Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) (Gibco Invitrogen GmbH) for 30 min at room temperature (RT). After fixation, PFA was removed by three washing steps with PBS (5 min each), and cells were blocked with 0.3% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Biomol GmbH) in PBS for 1 h at RT. First, extracellular bacteria were stained for 1 h at RT with a 1 : 1000 dilution of a polyclonal mouse anti-P. acnes antibody [9]. After three washing steps, extracellular bacteria were labelled with a secondary Cy2-conjugated goat-anti-mouse antibody (Dianova) at a dilution of 1 : 300 for 1 h at RT. Following additional three washing steps, cells were permeabilized for 30 min at RT using 0.1% Triton X-100 (Calbiochem) in PBS containing 0.3% BSA. After permeabilization, intracellular bacteria were stained for 1 h at RT with a 1 : 1000 dilution of the anti-P. acnes-antibody followed by three washing steps. Intracellular as well as extracellular bacteria were then labelled by 1 h incubation at RT with a Cy3-conjugated goat-anti-mouse antibody (Dianova). Actin was stained using a 1 : 100 dilution of Alexa Fluor 647 or 568 phalloidin (Invitrogen). Nuclei were stained using a 1 : 1000 dilution of Draq5 (Cell Signaling Technology Inc.) or DAPI. The lysosomal markers LAMP1 and cathepsin D and the early endosomal marker Rab5 were stained with a 1 : 50 dilution of rabbit antibody (Abcam) followed by secondary Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated donkey-anti-rabbit antibody (Invitrogen). After three washing steps, cover slips were mounted in Mowiol and stored at 4°C. Immunofluorescence staining was analyzed by confocal laser scanning microscopy using a Leica TCS SP equipped with an argon-krypton mixed gas laser.

2.9. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Slides containing sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) mouse prostate tissues were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a series of graded ethanol. For F4/80 and P. acnes IHC, slides were steamed for 40 min (anti-F4/80 antibody) or 17 min (anti-P. acnes antibody [9]) in high temperature target retrieval solution for antigen retrieval (Dako Cytomation). Slides were then incubated with primary antibodies against F4/80 (AbD Serotec) at a dilution of 1 : 10,000 for 45 min at room temperature or against P. acnes at a dilution of 1 : 2000 overnight at 4°C. For F4/80 IHC, slides were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal linker antibody to Rat IgG (Abcam) at 1 : 400. Slides were then incubated with secondary antibody (PowerVision, Leica Microsystems) for 45 min at room temperature. Staining was visualized using 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (Sigma FAST 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine tablets), and slides were counterstained with hematoxylin.

3. Results

3.1. Detection of P. acnes in Macrophages In Vivo

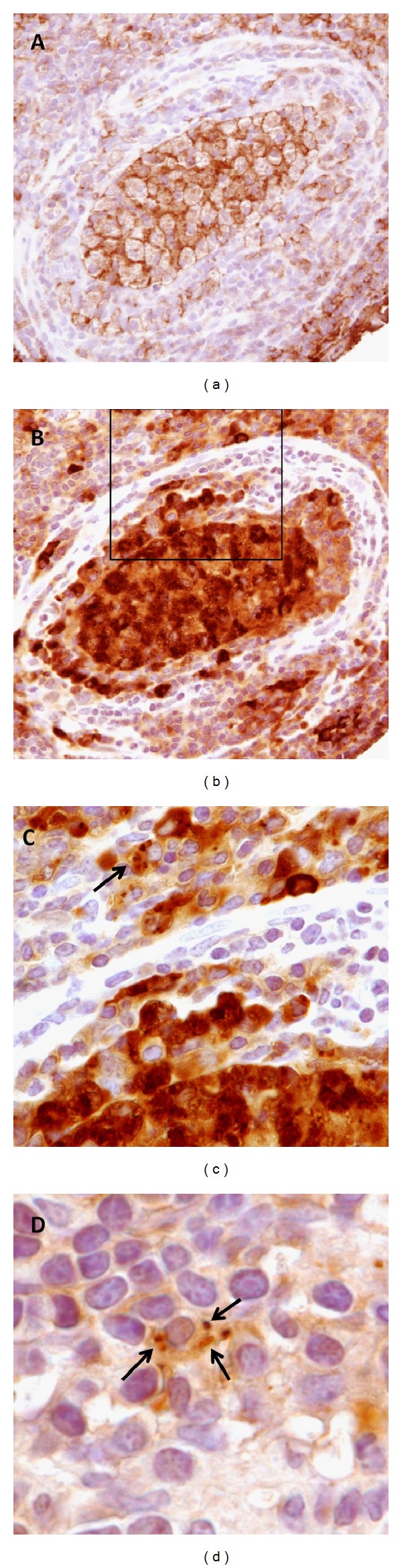

Recently, a mouse model of chronic prostatic inflammation was established [27], using the prostate-derived P. acnes isolate PA2 as infectious agent. At 2 weeks postinfection (p.i.), P. acnes could be detected in prostate-infiltrating macrophages as assessed by IHC with an anti-P. acnes antibody (Figure 1). Infiltrating macrophages in the glandular lumen contained multiple P. acnes cells (Figures 1(c) and 1(d)).

Figure 1.

Presence of P. acnes in mouse prostate-infiltrating macrophages. (a) Inflamed dorsal prostate gland 2 weeks after infection with P. acnes. Glandular lumen contains primarily macrophages as indicated by IHC for F4/80 macrophage marker. (b) Adjacent section stained with an anti-P. acnes antibody. Note dense accumulation of P. acnes cells in macrophages within glandular lumen. (c) Enlarged view of boxed area in (b). Single P. acnes cells can be visualized within prostate-infiltrating macrophages (arrow). (d) Additional image of P. acnes cells (arrows) in prostate-infiltrating macrophage as indicated by IHC with anti-P. acnes antibody.

3.2. A Clinical Prostate Isolate of P. acnes Persists Intracellularly in the Human Macrophage Cell Line THP-1

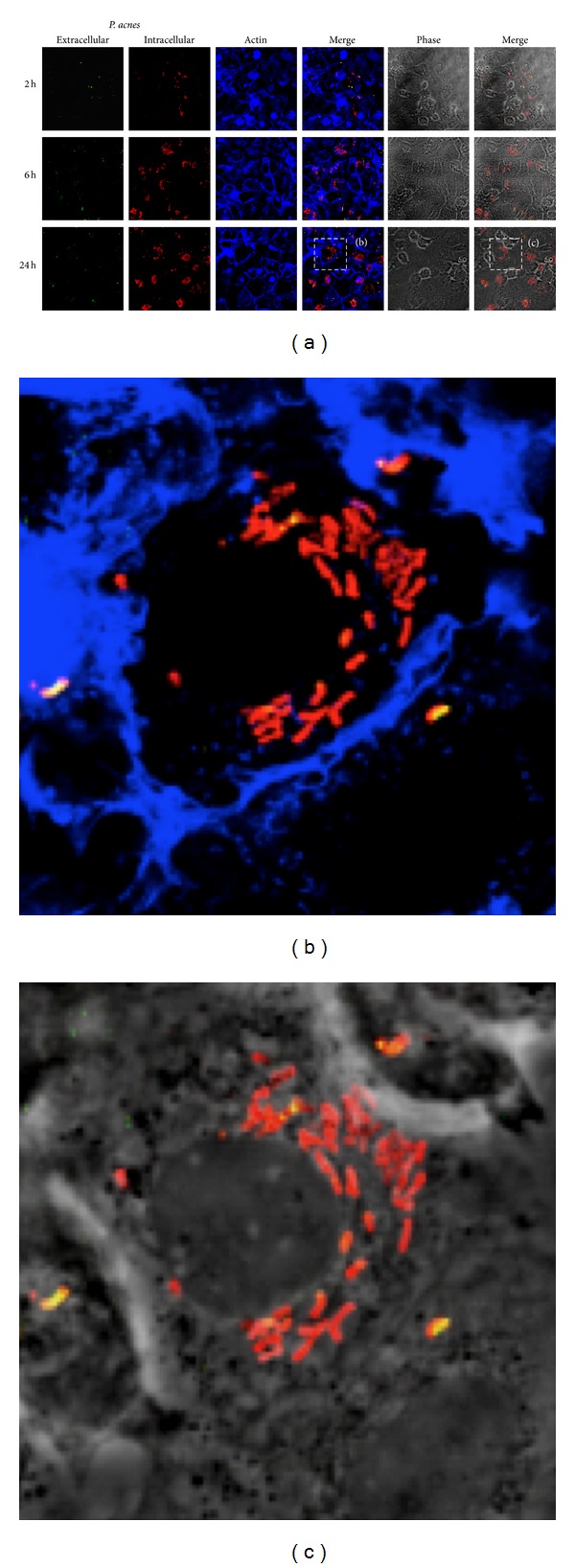

A macrophage cell culture model was established to investigate the intracellular fate of P. acnes. We first wanted to visualize the uptake and persistence of the clinical P. acnes strain P6 in the human macrophage cell line THP-1. The cells were differentiated by PMA treatment and stimulation with interferon gamma for 24 h prior to infection. Intracellular and extracellular bacteria could be detected by immunofluorescence (IF) staining at p.i. time points of 2 h, 6 h, and 24 h (Figure 2). Intracellular numbers of viable P. acnes increased between 2 h and 6 h p.i. as judged from colony forming unit (CFU) counts (data not shown). Massive intracellular clusters were present at 6 h and 24 h p.i. and were located around the nucleus (Figures 2(b) and 2(c)).

Figure 2.

Infection of THP-1 cells with prostate isolate P. acnes P6. (a) THP-1 cells were infected with P. acnes P6 at an MOI of 25. Infection was stopped after 2, 6, and 24 h. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA, and extracellular bacteria were stained with mouse polyclonal anti-P. acnes antibody and Cy-2 labelled goat-anti-mouse antibody (green). After permeabilization, intracellular bacteria were stained with mouse polyclonal anti-P. acnes antibody and Cy-3 labelled goat-anti-mouse antibody (red). Overlay of both stainings indicates extracellular bacteria (appearing yellow). Actin was stained with Alexa Fluor 647 phalloidin (blue). (b) and (c) Zoom-in on intracellular P. acnes (red) at 24 h p.i.

3.3. Absence of Intracellular Replication and Escape from the Host Cell

To investigate the possibility of intracellular replication or bacterial escape from the host cell, THP-1 cells were infected with P. acnes for 1 h, and extracellular bacteria were killed with antibiotic treatment for 2 h. The culture medium was replaced with antibiotic free medium, and the number of intracellular bacteria and escaped bacteria in the medium were determined after 2 h, 6 h, and 24 h of infection by CFU counts. We did not observe intracellular replication of P. acnes nor bacterial escape from the host cell (data not shown).

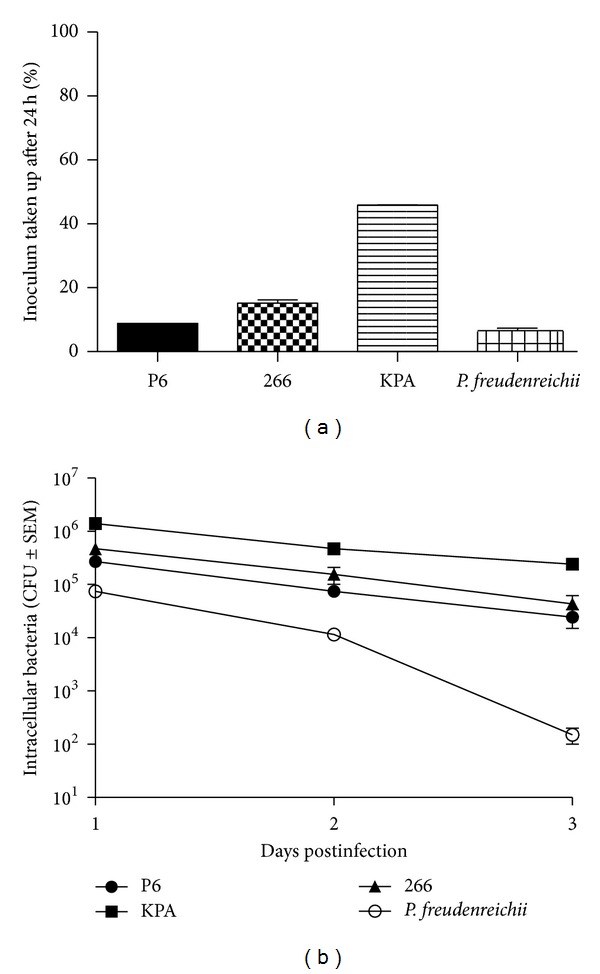

3.4. Comparison of Intracellular Viability of Different P. acnes Wild-Type Strains and P. freudenreichii

To investigate if intracellular persistence in macrophages is a trait common to P. acnes strains, we chose three strains, isolated from distinct body sites and belonging to different multilocus sequence types (MLSTs): the clinical prostate isolate P6 (ST33, type I-2), the skin isolate KPA171202 (ST34, type I-2), and the lung isolate 266 (ST18, type I-1a) [9, 25, 26]. In addition, a comparison was made to the dairy Propionibacterium freudenreichii (P. freudenreichii), which is not associated with humans, in order to assess if persistence is a trait attributed to all Propionibacteria or to P. acnes alone. We also wanted to test if intracellular bacteria are still alive and able to replicate after isolation from macrophages, which could be important for the persistence in host tissue and potentially for invasion of other cell types. After 24 h p.i., extracellular bacteria were killed by antibiotic treatment, and presence of live intracellular bacteria was determined over a time course of 3 days by plating of cell lysates on Brucella agar plates and CFU counts. Propionibacteria of all 4 strains recovered from THP-1 cells were viable and able to replicate on agar plates. The initial inoculum of each strain was calculated and set to 100%. At 24 h p.i. viable bacteria could be found intracellularly: 8.9% (±0.1%) of the initial inoculation of strain P6, 45.9% (±0.1%) of KPA, 15.2% (±1.4%) of 266, and 6.3% (±1.2%) of P. freudenreichii, showing strain-dependent differences in the uptake rate by macrophages (Figure 3(a)). No increase in CFU was observed for any of the used strains over the time course, indicative of the absence of intracellular replication. The CFU of intracellular P. acnes stayed stable over 3-day time course, while the CFU of P. freudenreichii dropped more than 2 logs from day one to day 3 (Figure 3(b)). This experiment showed that intracellular survival and persistence is common to P. acnes strains but not to P. freudenreichii.

Figure 3.

Intracellular viability of propionibacteria in THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were infected with P. acnes strains P6, KPA and 266, and P. freudenreichii at an MOI of 3. Extracellular bacteria were killed after 24 h by 3 h incubation with 300 μg/mL gentamicin. 100 μg/mL gentamicin was kept in the medium at all times to prevent reinfection with extracellular bacteria. Cells were lysed with 0.5% saponin, and remains were scraped off and mixed by vortexing. A dilution series was plated out on Brucella agar plates to determine viable intracellular bacteria by determining CFUs after 5 days of incubation at 37°C under anaerobic conditions. Data were evaluated using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism. Values represent mean of n = 2 ± SEM. (a) Presence of intracellular bacteria at 24 h p.i., compared to original inoculum (100%). (b) CFU counts of intracellular bacteria over a time course of 3 days.

3.5. Persistence of P. acnes in THP-1 Cells Does Not Cause Host Cell Death

In order to observe host cell fitness and survival during long-term P. acnes infection, a SYTOX green nucleic acid staining was performed on P. acnes strain P6-infected THP-1 cells at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h p.i. At 24 h p.i., 6.1% (±0.1%) of dead cells were observed in P6-infected THP-1 cells, compared to 4.7% (±0.2%) in noninfected cells (data not shown). This number increased to 7.0% (±0.9%) in infected and 6.5% (±0.3%) in noninfected cells at 72 h p.i. Thus, P. acnes P6 infection does not damage or kill THP-1 cells.

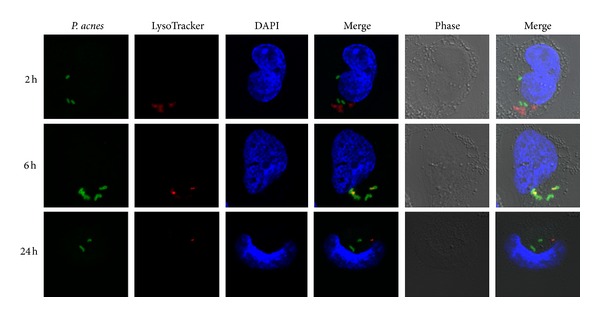

3.6. Transient Acidification of P. acnes-Containing Phagosomes

The observed persistence of P. acnes in activated THP-1 cells indicates that P. acnes is able to prevent or delay intracellular degradation. Upon engulfment by THP-1, bacteria are typically located in phagosomes. Via recurrent fusion and fission events with compartments of the endocytic pathway, the bacteria-containing phagosomes get gradually acidified in order to arrest the growth of entrapped bacteria and activate degrading enzymes for bacterial lysis [16–20]. To assess the process and state of acidification of the P. acnes-containing phagosomes, we performed infections of THP-1 cells in the presence of the acidotropic dye LysoTracker Red DND-99 that stains acidified cellular compartments. At early time points (2 h p.i.) no acidification of P. acnes-containing compartments can be detected, but at 6 h p.i. most bacteria-containing phagosomes are acidified (Figure 4). Interestingly, the acidification is gone at later time points (24 h p.i.), which could indicate the bacterial escape from phagosomes or intraphagosomal pH neutralization.

Figure 4.

Confocal analysis of LysoTracker-treated THP-1 cells infected with P. acnes. To visualize acidified cellular compartments the acidotropic dye LysoTracker Red DND-99 was used (red). Intracellular P. acnes were stained in green. Colocalization of P. acnes and LysoTracker, indicative of an acidified P. acnes-containing phagosome, was apparent at 6 h p.i. (yellow/orange) but not at 2 h and 24 h p.i. Shown are representative images from two independent infection experiments.

3.7. Intracellular P. acnes Do Not Colocalize with the Lysosomal Marker LAMP1 in THP-1 Cells 24 h p.i

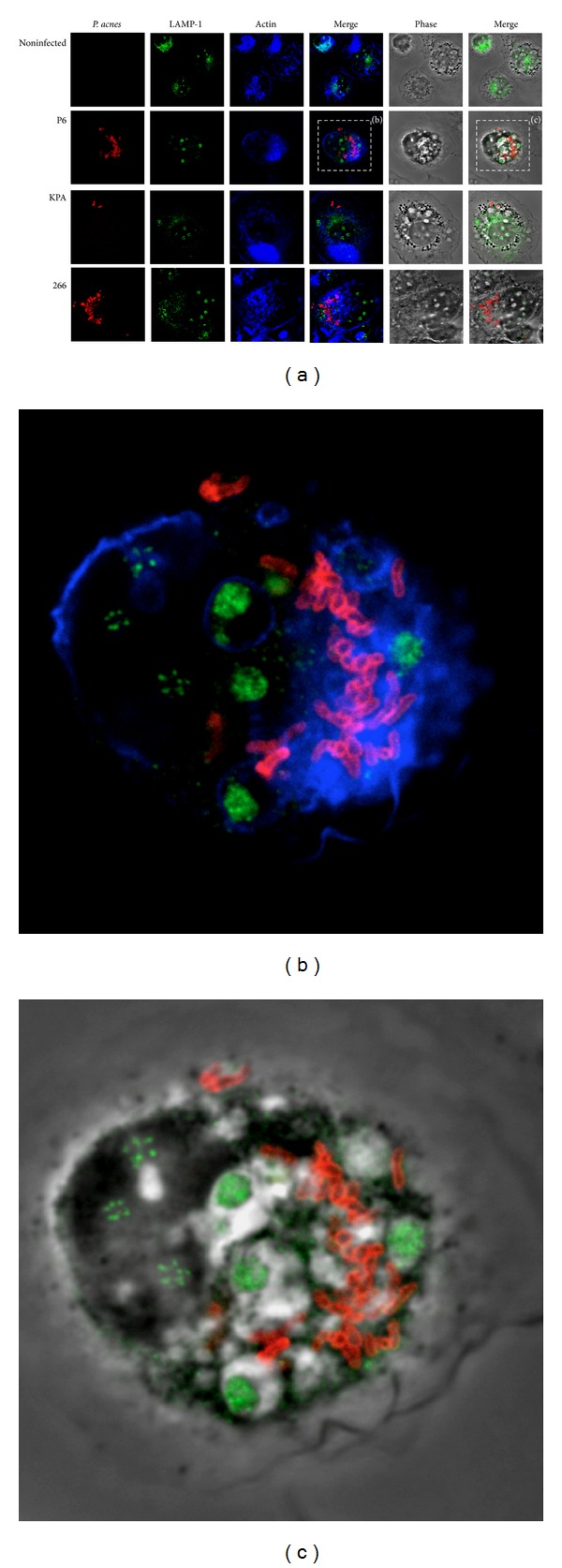

In order to further characterize the state of intracellular P. acnes at the time of 24 h postinfection we investigated the presence of a typical markers of late phagosomes, the lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1). This protein is one of the most abundant integral membrane proteins of phagolysosomes and has been shown to be essential for successful maturation from early to late stages [28]. Immunofluorescence staining of intracellular bacteria and LAMP1 was performed at 24 h p.i. No colocalization with LAMP1 was observed (Figure 5). This result supports the hypothesis that intracellular P. acnes do not reach the state of typical phagolysosomes.

Figure 5.

Confocal analysis of P. acnes and LAMP1 in THP-1 cells at 24 h p.i. (a) THP-1 cells were infected with P. acnes wild-type strains P6, KPA and 266 at an MOI of 3 for 24 h. Extracellular bacteria were killed with 300 μg/mL gentamycin and removed by washing steps. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and intracellular bacteria were stained with mouse polyclonal anti-P. acnes antibody and Cy-3 labelled donkey-anti-mouse antibody (red). The lysosomal marker LAMP1 was stained with rabbit-anti-LAMP1 antibody and Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated donkey-anti-rabbit-antibody (green). Actin was stained with Alexa Fluor 647 phalloidin (blue). (b) and (c) Zoom-in on cells infected with P. acnes P6.

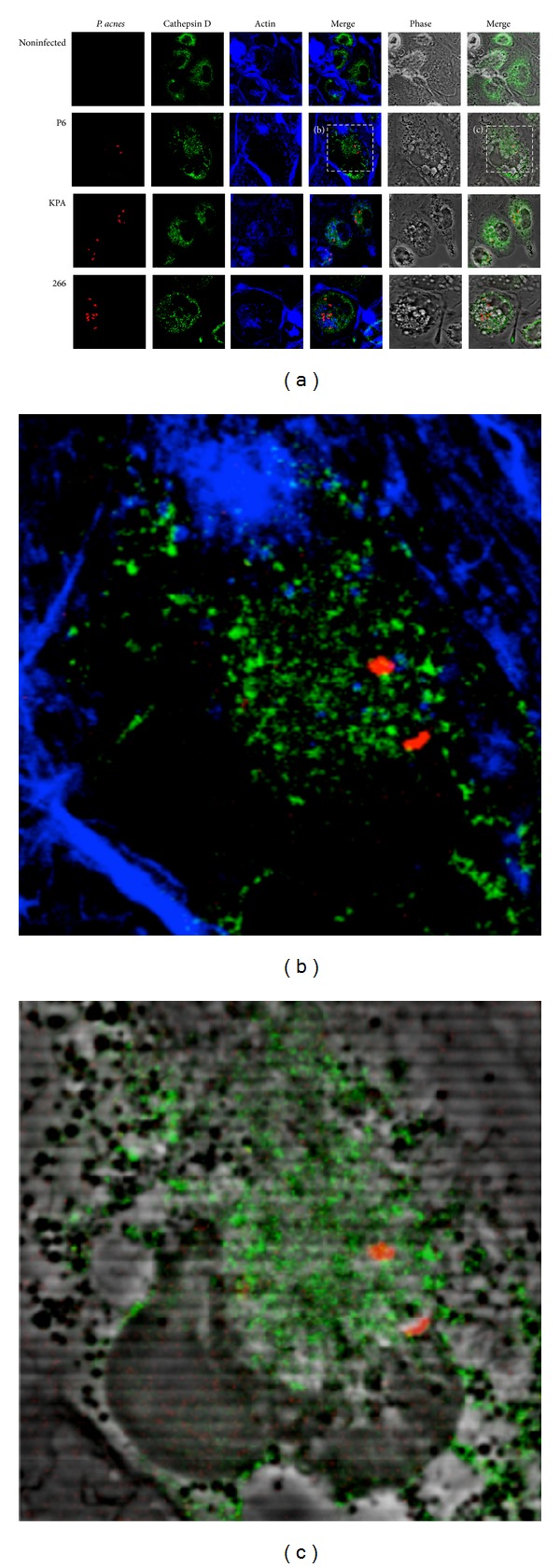

3.8. Intracellular P. acnes in THP-1 Cells Do Not Colocalize with the Lysosomal Marker Cathepsin D at 24 h p.i

To further strengthen the hypothesis that intracellular P. acnes do not end up in functional phagolysosomes we performed IF staining of the aspartic endopeptidase cathepsin D, which is a typical hydrolytic enzyme found in mature phagolysosomes [29]. Again, no colocalization of cathepsin D with intracellular P. acnes was observed (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Confocal analysis of P. acnes and cathepsin D in THP-1 cells at 24 h p.i. (a) Experiments were performed as described in Figure 5 legend. The lysosomal marker cathepsin D was stained with rabbit-anti-cathepsin D antibody and Cy2-conjugated donkey-anti-rabbit antibody (green). Intracellular P. acnes P6 (red), actin (blue). (b) and (c) Zoom-in on cells infected with P. acnes P6.

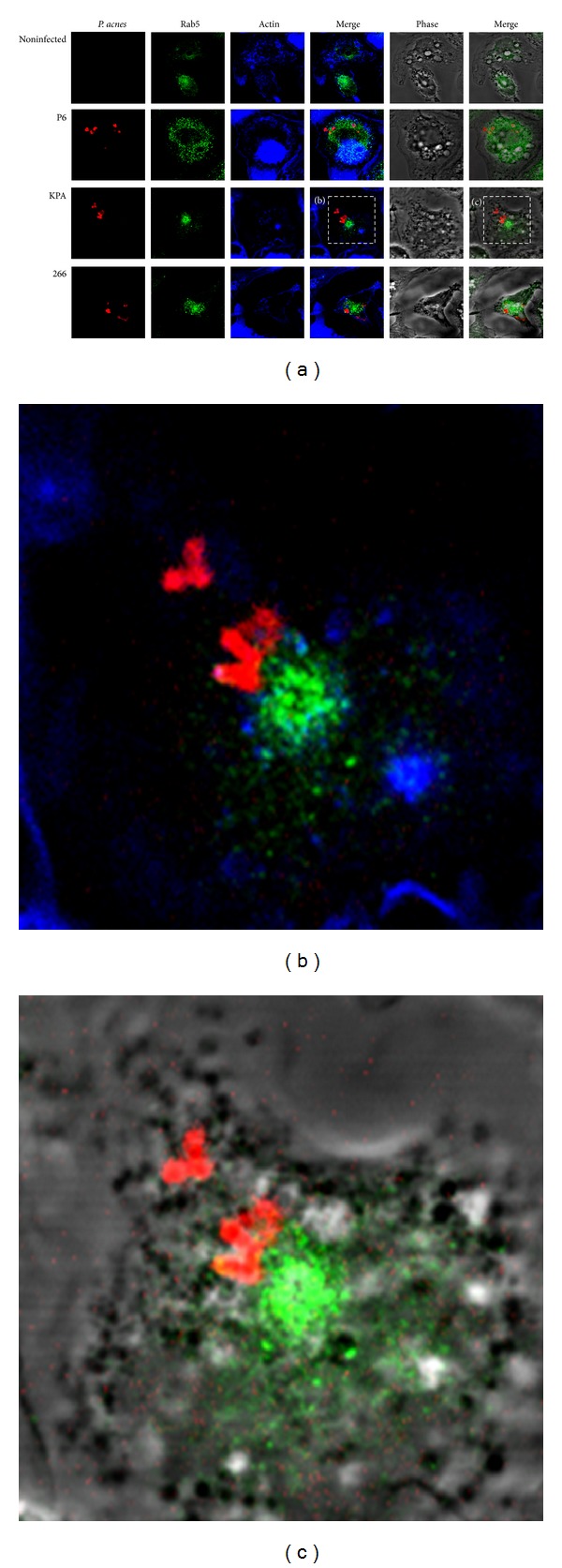

3.9. Intracellular P. acnes in THP-1 Cells Do Not Colocalize with the Early Endosomal Marker Rab5 at 24 h p.i

We did not find any colocalization of P. acnes with prominent lysosomal markers. Thus, we decided to investigate the possibility of a phagosomal maturation arrest in an early stage. This was shown for the persistent intracellular pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis; bacteria-containing vacuoles acquire the early endosome marker Rab5 but no markers of late endosomes or lysosomes [30]. IF staining of Rab5 and intracellular P. acnes in THP-1 cells at 24 h p.i. showed no colocalization (Figure 7). This suggests that P. acnes persistence and survival in macrophages is not due to an arrest at an early phagosomal stage. We also wanted to investigate the possibility of early acquisition and rapid loss of Rab5, as described for some other pathogens including Salmonella species. Synchronized phagocytosis was stopped after 15, 30, and 45 min and 1 and 2 h. The staining pattern of Rab5 did not change over the time course observed (data not shown). However, confocal analysis showed only very few intracellular P. acnes at the respective times; thus we cannot rule out the possibility of early Rab5 acquisition and subsequent rapid loss.

Figure 7.

Confocal analysis of P. acnes and Rab5 in THP-1 cells at 24 h p.i. (a) Experiments were performed as described in Figure 5 legend. The early endosome marker Rab5 was stained with rabbit-anti-Rab5 antibody and Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated donkey-anti-rabbit antibody (green). Intracellular P. acnes P6 (red), Actin (blue). (b) and (c) Zoom-in on cells infected with P. acnes P6.

4. Discussion

The intracellular lifecycle of P. acnes has not been studied in much detail so far. Fassi Fehri et al. [9] performed electron microscopy of the prostate epithelial cell line RWPE1, where P. acnes was located in intracellular vacuoles, either as single bacteria or in small clusters. These findings were similar to results obtained by Tanabe et al. [14], who showed that P. acnes isolates from sarcoidosis patients can invade the epithelial cell lines A549 and HRK293T. Previous research has also shown that professional phagocytes fail to clear P. acnes; not only are PMNs and monocytes unable to degrade P. acnes in vitro [23], but also intact bacteria have been found intracellularly in murine macrophages 6 days after injection [21]. A recent study showed that P. acnes can lead to a chronic inflammation of the mouse prostate; introduction of P. acnes into the mouse prostate via transurethral catheterization and inoculation led to chronic inflammation of the dorsal lobe of the prostate that persisted for at least 8 weeks after inoculation [27]. Similar results have been obtained in a rat model [31]. These observations provide evidence for the existence of P. acnes mechanisms to promote intracellular survival and persistence.

We showed here that P. acnes can be detected in vivo in prostate-infiltrating macrophages of the mouse at 2 weeks after P. acnes inoculation. In the human macrophage cell line THP-1 P. acnes not only survives but also persists. There are no signs of intracellular replication or escape from the host cell, and the presence of intracellular bacteria does not cause host cell death. Regarding the fate of THP-1 engulfed P. acnes, we detected intracellular acidification of P. acnes-containing compartments, which was transient. We could not detect colocalization with the late lysosomal markers LAMP1 and cathepsin D, or with the early endosomal marker Rab5 after 24 h of infection. The nonpathogenic relative P. freudenreichii is slowly degraded by THP-1 cells, which hints at a P. acnes-specific trait that confers protection to phagosomal degradation. Our data suggest a P. acnes-specific diversion or blockage of the phagosome maturation pathway and a possible bacterial escape from the phagosomal compartment. We could not reveal in this study at which step the maturation of P. acnes-containing phagosomes stops or diverges from the typical maturation pathway.

Intracellular bacteria persist but do not multiply within or escape from the host cell or cause host cell death. These findings underline the assumption that P. acnes is not a typical intracellular pathogen but still confers means to avoid the phagolysosomal degradation machinery. Identifying differences in uptake and persistence of different strains/phylotypes of P. acnes could help to elucidate the mechanism of protection from degradation. The comparison of P. acnes strains indicated strain-specific uptake efficiencies. But the mechanism to evade degradation seems to be conserved and present in all three wild-type P. acnes strains. On the other hand, P. freudenreichii does not possess the P. acnes survival trait and was slowly degraded in THP-1 cells. The genome of P. freudenreichii has been sequenced [32]; 60% of P. acnes coding sequences have an ortholog in P. freudenreichii. However, none of the putative virulence factors of P. acnes such as sialidases, dermatan-sulphate adhesins, and Christie-Atkins-Munch-Perterson (CAMP) factors were identified in P. freudenreichii. We hypothesise that the P. acnes-specific survival trait is mediated either by a P. acnes-specific virulence factor or by differences of the cell wall composition. It was proposed in the 1980s that intracellular persistence of P. acnes is a result of the thick and tightly cross-linked cell wall that is resistant to the action of degrading and oxidizing enzymes of the host defence machinery [23, 33].

We observe acidification of the P. acnes-containing compartment at 6 h postinfection; at later time points (24 h p.i.) this was reverted as we detected no signs of acidification surrounding the intracellular location of P. acnes. One explanation of this observation is a P. acnes mechanism to counteract intraphagosomal acidification. Interestingly, a previous study identified a P. acnes system that is highly expressed and that can neutralize acidic conditions: the arginine deiminase (ADI) pathway [26]. This system converts arginine to ornithine, thereby generating NH3 and ATP. The ADI pathway of Listeria monocytogenes has been implicated in the bacterial survival within macrophage phagosomes [34]. Another possibility is a bacterial escape from the phagosome. Interestingly, a recent study by Nakatsuji et al. suggests that CAMP factors of P. acnes could act together with a membrane-associated form of mammalian sphingomyelinases and facilitate phagosomal escape of P. acnes [35]. CAMP factors possess cohemolytic activity and have been reported to be pore-forming toxins [36, 37].

5. Conclusions

The present study allows a first insight into possible check points of interference or blockage of the phagosomal maturation pathway in macrophages by P. acnes and opens up many interesting questions about the P. acnes intracellular lifecycle, including the intriguing possibility that P. acnes uses macrophages as a niche for survival and spread. Further investigations will help us to identify and understand the underlying mechanisms of intracellular survival and persistence and might help to develop strategies of P. acnes eradication in diseased patients. This could bring helpful innovations in the fight against chronic P. acnes infections and the associated pathologies.

Acknowledgments

Debika Biswal Shinohara is funded by a training Grant awarded by the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences (ES07141). This work was funded in part by the Johns Hopkins University Prostate Cancer SPORE Grant (5P50CA058236) Young Investigator Award (to Karen S. Sfanos), the Chris and Felicia Evensen Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF) Young Investigator Award (to Karen S. Sfanos), and the European Skin Research Foundation (ESRF) New Investigator Award (to Holger Brüggemann).

References

- 1.Grice EA, Segre JA. The skin microbiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2011;9(4):244–253. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leeming JP, Holland KT, Cuncliffe WJ. The microbial colonization of inflamed acne vulgaris lesions. British Journal of Dermatology. 1988;118(2):203–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leyden JJ. The evolving role of Propionibacterium acnes in acne. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2001;20(3):139–143. doi: 10.1053/sder.2001.28207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bojar RA, Holland KT. Acne and Propionibacterium acnes . Clinics in Dermatology. 2004;22(5):375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grange PA, Weill B, Dupin N, Batteux F. Does inflammatory acne result from imbalance in the keratinocyte innate immune response? Microbes and Infection. 2010;12(14-15):1085–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dessinioti C, Katsambas AD. The role of Propionibacterium acnes in acne pathogenesis: facts and controversies. Clinics in Dermatology. 2010;28(1):2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. The Lancet. 2012;379(9813):361–372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perry A, Lambert P. Propionibacterium acnes: infection beyond the skin. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 2011;9(12):1149–1156. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fassi Fehri L, Mak TN, Laube B, et al. Prevalence of Propionibacterium acnes in diseased prostates and its inflammatory and transforming activity on prostate epithelial cells. International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2011;301(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mak TN, Yu SH, De Marzo AM, et al. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis of Propionibacterium acnes isolates from radical prostatectomy specimens. Prostate. 2013;73(7):770–777. doi: 10.1002/pros.22621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen RJ, Shannon BA, McNeal JE, Shannon T, Garrett KL. Propionibacterium acnes associated with inflammation in radical prostatectomy specimens: a possible link to cancer evolution? Journal of Urology. 2005;173(6):1969–1974. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158161.15277.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexeyev OA, Marklund I, Shannon B, et al. Direct visualization of Propionibacterium acnes in prostate tissue by multicolor fluorescent in situ hybridization assay. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2007;45(11):3721–3728. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01543-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sfanos KS, Sauvageot J, Fedor HL, Dick JD, De Marzo AM, Isaacs WB. A molecular analysis of prokaryotic and viral DNA sequences in prostate tissue from patients with prostate cancer indicates the presence of multiple and diverse microorganisms. Prostate. 2008;68(3):306–320. doi: 10.1002/pros.20680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanabe T, Ishige I, Suzuki Y, et al. Sarcoidosis and NOD1 variation with impaired recognition of intracellular Propionibacterium acnes . Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2006;1762(9):794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mak TN, Fischer N, Laube B, et al. Propionibacterium acnes host cell tropism contributes to vimentin-mediated invasion and induction of inflammation. Cellular Microbiology. 2012;14(11):1720–1733. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desjardins M. Biogenesis of phagolysosomes: the “kiss and run” hypothesis. Trends in Cell Biology. 1995;5(5):183–186. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88989-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beron W, Alverez-Dominguez C, Mayorga L, Stahl PD. Membrane trafficking along the phagocytic pathway. Trends in Cell Biology. 1995;5(3):100–104. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88958-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aderem A, Underhill DM. Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages. Annual Review of Immunology. 1999;17:593–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amer AO, Swanson MS. A phagosome of one's own: a microbial guide to life in the macrophage. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2002;5(1):56–61. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00286-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott CC, Botelho RJ, Grinstein S. Phagosome maturation: a few bugs in the system. Journal of Membrane Biology. 2003;193(3):137–152. doi: 10.1007/s00232-002-2008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuttle RL, North RJ. Mechanisms of antitumor action of Corynebacterium parvum: nonspecific tumor cell destruction at site of an immunologically mediated sensitivity reaction to C. parvum. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1975;55(6):1403–1411. doi: 10.1093/jnci/55.6.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott MT, Milas L. The distribution and persistence in vivo of Corynebacterium parvum in relation to its antitumor activity. Cancer Research. 1977;37(6):1673–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webster GF, Leyden JJ, Musson RA, Douglas SD. Susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes to killing and degradation by human neutrophils and monocytes in vitro. Infection and Immunity. 1985;49(1):116–121. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.1.116-121.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Negi M, Takemura T, Guzman J, et al. Localization of Propionibacterium acnes in granulomas supports a possible etiologic link between sarcoidosis and the bacterium. Modern Pathology. 2012;25(9):1284–1297. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brüggemann H, Henne A, Hoster F, et al. The complete genome sequence of Propionibacterium acnes, a commensal of human skin. Science. 2004;305(5684):671–673. doi: 10.1126/science.1100330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brzuszkiewicz E, Weiner J, Wollherr A, et al. Comparative genomics and transcriptomics of Propionibacterium acnes . PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021581.e21581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinohara DB, Vaghasia A, Yu SH, et al. A mouse model of chronic prostatic inflammation using a human prostate cancer-derived isolate of Propionibacterium acnes . Prostate. 2013;73(9):1007–1015. doi: 10.1002/pros.22648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huynh KK, Eskelinen E, Scott CC, Malevanets A, Saftig P, Grinstein S. LAMP proteins are required for fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. The EMBO Journal. 2007;26(2):313–324. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benes P, Vetvicka V, Fusek M. Cathepsin D-Many functions of one aspartic protease. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2008;68(1):12–28. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Via LE, Deretic D, Ulmer RJ, Hibler NS, Huber LA, Deretic V. Arrest of mycobacterial phagosome maturation is caused by a block in vesicle fusion between stages controlled by rab5 and rab7. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(20):13326–13331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsson J, Drott JB, Laurantzon L, et al. Chronic prostatic infection and inflammation by Propionibacterium acnes in a rat prostate infection model. PLoS One. 2012;7(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051434.e51434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falentin H, Deutsch S, Jan G, et al. The complete genome of propionibacterium freudenreichii CIRM-BIA1T, a hardy actinobacterium with food and probiotic applications. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011748.e11748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pringle AT, Cummins CS, Bishop BF, Viers VS. Fate of vaccines of Propionibacterium acnes after phagocytosis by murine macrophages. Infection and Immunity. 1982;38(1):371–374. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.1.371-374.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryan S, Begley M, Gahan CGM, Hill C. Molecular characterization of the arginine deiminase system in Listeria monocytogenes: regulation and role in acid tolerance. Environmental Microbiology. 2009;11(2):432–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakatsuji T, Tang DC, Zhang L, Gallo RL, Huang C. Propionibacterium acnes camp factor and host acid sphingomyelinase contribute to bacterial virulence: potential targets for inflammatory acne treatment. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014797.e14797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valanne S, McDowell A, Ramage G, et al. CAMP factor homologues in Propionibacterium acnes: a new protein family differentially expressed by types I and II. Microbiology. 2005;151(5):1369–1379. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27788-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lang S, Palmer M. Characterization of Streptococcus agalactiae CAMP factor as a pore-forming toxin. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(40):38167–38173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]