Abstract

Lentiviral Gag proteins contain a short spacer sequence that separates the capsid (CA) from the downstream nucleocapsid (NC) domain. This short spacer has been shown to play an important role in the assembly of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). We have now extended this finding to the CA-NC spacer motif within the Gag protein of bovine immunodeficiency virus (BIV). Mutation of this latter spacer sequence led to dramatic reductions in virus production, which was mainly attributed to the severely disrupted association of the mutated Gag with the plasma membrane, as shown by the results of membrane flotation assays and confocal microscopy. Detailed mutagenesis analysis of the BIV CA-NC spacer region for virus assembly determinants led to the identification of two key residues, L368 and M372, which are separated by three amino acids, 369-VAA-371. Incidentally, the same two residues are present within the HIV-1 CA-NC spacer region at positions 364 and 368 and have also been shown to be crucial for HIV-1 assembly. Regardless of this conservation between these two viruses, the BIV CA-NC spacer could not be replaced by its HIV-1 counterpart without decreasing virus production, as opposed to its successful replacement by the CA-NC spacer sequences from the nonprimate lentiviruses such as feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), equine infectious anemia virus and visna virus, with the sequence from FIV showing the highest effectiveness in this regard. Taken together, these data suggest a pivotal role for the CA-NC spacer region in the assembly of BIV Gag; however, the mechanism involved therein may differ from that for the HIV-1 CA-NC spacer.

Retroviral Gag proteins drive the formation of immature virus particles in which Gag molecules display a radial arrangement underneath the viral membrane. In order to acquire infectiousness, these immature particles must undergo a maturation process during which the Gag precursor is cleaved by the viral protease into three major structural proteins, including matrix (MA), capsid (CA), and nucleocapsid (NC) proteins. Within the virus particle, these mature proteins form distinct substructures, in which MA is attached to the viral membrane, CA molecules constitute morphologically distinct cores, and NC is associated with viral genomic RNA within the core structure (for a review, see reference 35).

Aside from the MA, CA, and NC domains, retrovirus Gag proteins contain relatively short peptides that are not well conserved between different retroviruses in terms of their positions, lengths, and compositions. Nonetheless, these peptide sequences do play important roles in Gag assembly. A well-characterized example is the late domain function that has been mapped to a PTAP tetrapeptide region within p6 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Gag (12, 16), a PPPY motif within p2b of Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) Gag (41, 43), and a YPDL sequence within p9 of equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) Gag (30, 31). The PPPY late domain motif was also identified within p12 of murine leukemia virus Gag (46, 47) and pp24/16 of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus Gag (44).

A second example concerns the CA-NC spacer region that has been shown to regulate the temporal processing of Gag in RSV and HIV-1 and thus controls the proper maturation of virus particles. In this context, studies have shown that removal of this spacer sequence from RSV Gag led to the generation of noninfectious virus particles exhibiting heterogeneous morphology and containing unstable cores (4). Similarly, blockade of the release of CA from the downstream spacer sequence SP1 in the case of HIV-1 Gag prevented condensation of the capsid structure and thus resulted in the formation of a spherical instead of a conical core (39). Notably, the CA-NC spacer plays a more active role in the assembly of HIV-1 Gag than in the case of RSV, since deletion of the SP1 sequence virtually eliminated HIV-1 production (1, 22, 28) as opposed to the efficient virus assembly seen with RSV Gag that lacked the CA-NC spacer (4).

Not all retrovirus Gag proteins have a CA-NC spacer region, such as those from mouse mammary tumor virus and murine leukemia virus. Interestingly, all of the lentiviral Gag proteins contain a spacer region between the CA and NC domains (5, 14, 15, 23, 37). Moreover, the results of computer modeling on the basis of the PHD program (PHD represents “profile network from Heidelberg”) indicated that an α-helix extends from the C terminus of the lentiviral CA domain into the downstream spacer region (33). This putative helical structure has been proposed to regulate HIV-1 assembly (1). It is thus intriguing to speculate that this active role of SP1 in the assembly of HIV-1 Gag may also be assigned to the equivalent spacer regions within Gag proteins from the other lentiviruses. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the potential involvement of the CA-NC spacer, termed p3, in the assembly of the Gag protein of bovine immunodeficiency virus (BIV), which represents a nonprimate lentivirus (11). The p3 region consists of 25 amino acids and is the longest of its kind among the retroviruses (37). The results of our studies show that mutation of the p3 sequence led to a severely diminished yield of virus particles. Two residues, L368 and M372, were further identified within p3 to be indispensable for virus production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

The HIV-1 and BIV proviral DNA clones, BH10 and BIV127, respectively, were used as starting materials for the following mutagenesis experiments. Domain structures of the BIV/HIV-1 chimeric Gag proteins C2 and C3 are illustrated in Fig. 1A and were generated by PCR. Three different primer pairs were used for PCR: (i) pC1 (5′-GCTTCTTTTCTAACTCCCTTCTCTTCATCTCTCTCCTTCTAGCCTCCG-3′; the first 28 nucleotides [nt] are from BIV [nt 736 to 709]; the following 20 nt are from BH10 [nt 779 to 770]) and pBssH-S (5′-CTGAAGCGCGCACGGCAAGAGG-3′; BH10 [nt 706 to 727]), (ii) pC2 (5′-GTGGGATCTCAGAAATCAAAGATGCAATTTGCTGAAGCAATGAGCCAAG-3′; the first 30 nt are from BIV [nt 1780 to 1809]; the following 19 nt are from BH10 [nt 1879 to 1897]) and pNC-A (5′-TTAGCCTGTCTCTCAGTACAATC-3′; BH10 [nt 2084 to 2062]), and (iii) pC3 (5′-GCAGTCTTGCCTCACACACCAGAAGCATATATGCAGAGAGGCAATTTTAG-3′; the first30 nt are from BIV [nt 1855 to 1884]; the next 21 nt are from BH10 [nt 1921 to 1941]) and pNC-A. The products generated from PCR with the first two primer pairs were used as megaprimers in a second round of PCR, with BIV DNA as a template. This PCR was performed for 15 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 4 min; primers pBssH-S and pNC-A were then added into the reaction mixture, and the PCR was run for 25 more cycles. The final PCR products were digested with restriction enzymes BssHII and ApaI and inserted into BH10 DNA that had been digested with the same two enzymes. The DNA clone thus generated encodes the C2 chimeric Gag protein (Fig. 1A). The C3 DNA was constructed on the basis of the same strategy through use of primers pC1 and pBssH-S and primers pC3 and pNC-A.

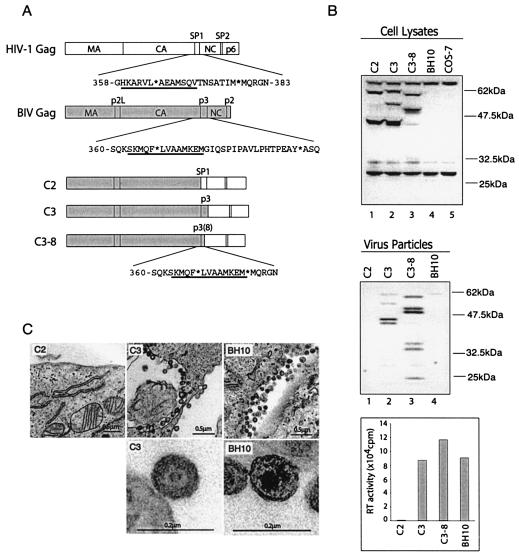

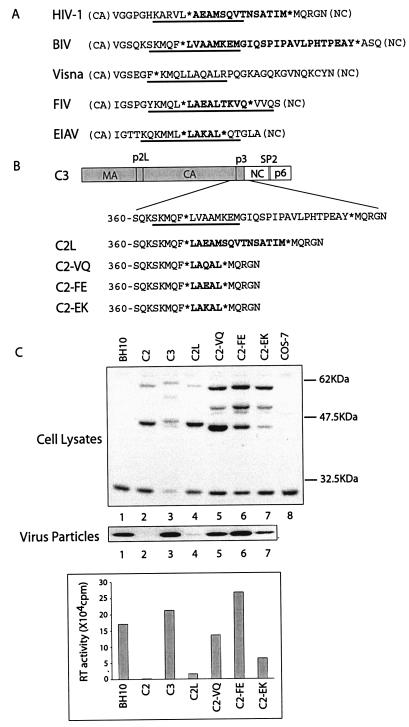

FIG. 1.

Effects of the substituted BIV p3 sequence on virus production. (A) Illustration of the domain structures of Gag and sequences of the CA-NC spacer for both HIV-1 and BIV. Asterisks denote the cleavage sites by the viral protease. The underlined amino acid sequences are predicted to adopt α-helix based on the results of computer modeling (1, 33). The C2, C3, and C3-8 DNA constructs all contain the BIV MA-P2L-CA and HIV-1 NC-p1-p6 sequences; however, they differ in the sequences of the spacer between CA and NC: C2 contains the HIV-1 SP1 spacer, C3 has the BIV p3 spacer, and C3-8 possesses eight residues from the N terminus of the BIV p3 spacer. (B) Protein expression and virus production by the C2, C3, and C3-8 DNA constructs. Expression of viral Gag proteins within COS-7 cells was analyzed by Western blot with rabbit anti-BIV serum. Untransfected COS-7 cells were assayed in the Western blot as a negative control. Accumulation of the full-length chimeric Gag proteins (ca. 60 kDa) and the intermediate products of 44 kDa for C2 and C3, as well as 51 kDa for C3-8, is attributed to the incomplete cleavage of the BIV MA-P2L-CA-p3 domains by HIV-1 protease. Virus particles in the supernatants were collected by ultracentrifugation, and their levels were determined by both Western blot and RT assays. The wild-type HIV-1 BH10 was included as a control to evaluate the levels of virus production from these chimeric DNA constructs. It should be noted that the HIV-1 proteins are not reactive to anti-BIV antibodies in the Western blot. Amounts of BH10 particles were measured on the basis of RT activity levels. Protein markers are shown on the right side of the gels. (C) Virus particles observed by EM. The wild-type HIV-1 BH10 was included as a positive control to evaluate the efficiency of virus production by the C2 and C3 DNA constructs. The immature morphology associated with the C3 viruses is due to the incomplete processing of the chimeric Gag proteins by HIV-1 protease.

The C3-8 DNA construct was generated by PCR with primers pC3-8 (5′-GCAATTTTTGGTAGCAGCTATGAAAGAAATGATGCAGAGAGGCAATTTTAGG-3′; the first 31 nt are from BIV [nt 1410 to 1440], and the last 21 nt are from BH10 [nt 1921 to1941]) and pNC-A, with BH10 as a template. The resultant PCR products were used as a megaprimer, together with primer pBssH-S in a second round of PCR. The final PCR products were digested with restriction enzymes BssHII and ApaI and inserted into BH10 that had been digested with the same two enzymes. On the basis of the same strategy, the C2L, C2-VQ, C2-FE, and C2-EK DNA constructs were generated through the use of primers pC2L (5′-CTCAGAAATCAAAGATGCAATTTTTGGCTGAAGCAATGAGCCAAG-3′), pVQ (5′-CTCAGAAATCAAAGATGCAATTTTTAGCACAAGCTTTGATGCAGAGAGGCAATTTTAGGAAC-3′), pFE (5′-CTCAGAAATCAAAGATGCAATTTTTGGCAGAAGCTCTTATGCAGAGAGGCAATTTTAGGAAC-3′), and pEK (5′-CTCAGAAATCAAAGATGCAATTTTTGGCAAAAGCACTTATGCAGAGAGGCAATTTTAGGAAC-3′), respectively.

Substitution of the BIV Gag sequences across the CA-p3 boundary (spanning amino acids 363 to 375) in the context of the C3 construct was performed by PCR with the primers listed in Table 1, together with the antisense primer pNC-A. The resultant PCR products were used as primers in a second round of PCR, together with the sense primer pBssH-S. The final PCR products were digested with BssHII and ApaI and inserted into C3.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers that were used for mutagenesis

| Mutation | Primer sequencea | Position (nt)b |

|---|---|---|

| S363A | 5′-GTGGGATCTCAGAAAgCAAAGATGCAATTTTTGG-3′ | 1387-1420 |

| K364A | 5′-GGATCTCAGAAATCAgcGATGCAATTTTTGG-3′ | 1390-1420 |

| M365A | 5′-GATCTCAGAAATCAAAGgcGCAATTTTTGGTAG-3′ | 1391-1423 |

| Q366A | 5′-CAGAAATCAAAGATGgcATTTTTGGTAGCAG-3′ | 1396-1426 |

| F367A | 5′-GAAATCAAAGATGCAAgcTTTGGTAGCAGCTATG-3′ | 1398-1431 |

| L368A | 5′-CAAAGATGCAATTTgcGGTAGCAGCTATG-3′ | 1403-1431 |

| V369A | 5′-GATGCAATTTTTGGcAGCAGCTATGAAAG-3′ | 1407-1435 |

| A370V | 5′-GATGCAATTTTTGGTAGtAGCTATGAAAG-3′ | 1407-1435 |

| A371V | 5′-CAATTTTTGGTAGCAGtTATGAAAGAAATG-3′ | 1411-1440 |

| M372A | 5′-CAATTTTTGGTAGCAGCTgcGAAAGAAATGGGG-3′ | 1411-1443 |

| K373A | 5′-GGTAGCAGCTATGgcAGAAATGGGGATC-3′ | 1419-1446 |

| E374A | 5′-GTAGCAGCTATGAAAGcAATGGGGATCCAATC-3′ | 1420-1451 |

| M375A | 5′-GCAGCTATGAAAGAAgcGGGGATCCAATCACC-3′ | 1423-1454 |

| Q366G | 5′-CAGAAATCAAAGATGggcTTTTTGGTAGCAG-3′ | 1396-1426 |

| A370G | 5′-GATGCAATTTTTGGTAGgcGCTATGAAAG-3′ | 1407-1435 |

| K373G | 5′-GGTAGCAGCTATGggcGAAATGGGGATC-3′ | 1419-1446 |

Mutated nucleotides are denoted in lowercase type.

Nucleotide positions refer to the BIV RNA sequence.

The Gag-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein was generated as follows. The BH10-FS DNA contains a frameshift mutation in the gag gene (26) and was used as the starting material. This DNA construct allows the consistent expression of a complete Gag-GFP fusion protein when the GFP gene is attached to the C terminus of p6. The stop codon at the C terminus of p6 was first removed by PCR with the primers pAPA-S (5′-TGCAGGGCCCCTAGGAAAAAGGG-3′) and pNS (5′-ACTGGATATCCGCTGCCTGCAGTTGTGACGAGGGGTCGTTGCC-3′), and a PstI restriction site was inserted for subsequent cloning of the enhanced GFP (EGFP) sequence. The PCR products were digested with restriction enzymes ApaI and EcoR V and inserted into a subcloned fragment (nt 2005 to 5790) of BH10 within construct pSVK-AS. The GFP gene was amplified from the vector pIRES-EGFP (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.) by PCR with the primers 5′-GCACATCTGCAGGGAGCGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGCTGTTCACC-3′ and 5′-GCACATGATATCTCAGCTTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATG-3′ that harbor restriction sites for PstI and EcoRV, followed by digestion with these two enzymes and insertion into pSVK-AS. The HIV-1 DNA fragment (nt 2005 to 5790) was then cloned back into BH10 by using the restriction sites ApaI and SalI.

Cell culture and transfection.

COS-7 and HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Transfection was performed with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Burlington, Calif.) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Analysis of viral proteins.

At 48 h after transfection, the cells were collected and lysed in a buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% sodium azide, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors that block the activity of cellular proteases (Roche, Laval, Quebec, Canada). After clarification by using a GS-6R Beckman centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C, the cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting with either rabbit anti-BIV serum (provided by Denis Archambault, University of Quebec, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) or rabbit ant-HIV-1 NC serum (provided by Tracy L. Vagrin, National Cancer Institute-Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center). Virus particles in the culture fluids were pelleted through a 20% sucrose cushion by ultracentrifugation at 35,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C in a Beckman ultracentrifuge by using an SW41 rotor. Virus quantities were determined on the basis of either the levels of reverse transcriptase (RT) activity or the amounts of Gag proteins.

Membrane flotation assay.

Transfected COS-7 cells were washed three times with cold phosphate-buffered saline and then harvested and suspended in 1 ml of cold TNE buffer containing 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, and protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche). After Dounce homogenization on ice, homogenates were clarified at 3,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C in a Beckman GS-6R centrifuge to remove cell debris and nuclei, followed by ultracentrifugation at 26,500 rpm (100,000 × g) for 1 h at 4°C in an SW55 rotor. The pellets were suspended in 1 ml of TNE buffer (termed P100) and were assessed in membrane flotation assays as previously described (24).

Confocal microscopy and EM.

COS-7 cells that had been transfected with DNA constructs expressing the Gag-GFP fusion protein were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (in phosphate-buffered saline) at room temperature for 20 min. After a wash with phosphate-buffered saline, the cells were directly visualized with a Zeiss LSM410 laser-scanning microscope.

To perform electron microscopy (EM), transfected COS-7 cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, followed by treatment with 4% osmium tetroxide, and then routinely processed and embedded. Thin-sectioned samples were stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate and then visualized by using a JEOL JEM-2000 FX transmission electron microscope equipped with a Gatan 792 Bioscan 1,024- by 1,024-byte wide-angle multiscan charge-coupled device camera.

RESULTS

The p3 spacer sequence is required by BIV CA to generate virus particles.

The CA-NC spacer sequence SP1 regulates HIV-1 Gag assembly in concert with the adjacent CA region through formation of a putative α-helical structure (1). This function of SP1 is independent of the downstream NC sequence, since NC can be replaced by heterogeneous protein sequences without affecting virus production (2, 48, 49). In an effort to test these findings in the cases of other lentiviruses, we sought to determine whether the CA-NC spacer region p3 is needed by BIV Gag for its assembly and whether this potential function of p3 requires the downstream BIV NC sequence.

To address these two issues, we first generated a chimeric Gag protein, namely, C3 which contained the MA-P2L-CA-p3 sequences from BIV Gag and the NC-p1-p6 domains from HIV-1 Gag (Fig. 1A). Upon transfection of COS-7 cells, the C3 construct produced high levels of virus particles, as shown by the results of Western blot analyses and RT assays (Fig. 1B). However, a further replacement of the BIV p3 region by the HIV-1 SP1 sequence in construct C2 resulted in virtually a complete loss of virus production (Fig. 1B). Consistent with these biochemical results, the EM data revealed a large number of virus particles associated with cells that had been transfected with the C3 DNA but not with the C2 construct (Fig. 1C). The BIV127 cDNA clone was poorly expressed in COS-7 cells and thus was not used as a control for virus production. These experiments demonstrate that the BIV p3 sequence is essential for its upstream MA-P2L-CA domains to generate virus particles.

The first eight amino acids at the N terminus of p3 suffice to support virus production.

A putative α-helix has been reported to cross the HIV-1 CA-SP1 boundary region and may play an important role in the production of HIV-1 particles (1). Interestingly, the BIV CA-p3 boundary sequence also exhibits a high propensity to adopt an α-helix that spans amino acids 363 to 375 (Fig. 1A). Were this helical structure the major determinant within p3 for Gag assembly, then removal of amino acids 376 to 392 within p3, which are not involved in construction of this putative α-helix, should not affect virus production (Fig. 1A). To test this hypothesis, we generated a construct C3-8 that lacked the aforementioned amino acids from positions 376 to 392 (Fig. 1A). Indeed, transfection of the C3-8 DNA into COS-7 cells led to the generation of virus particles at levels similar to those produced by the C3 DNA (Fig. 1B). Therefore, the key elements within p3 for virus assembly must be among the first eight N-terminal residues spanning positions 368 to 375.

Amino acids K364, M365, L368, and M372 are essential for Gag assembly.

In an effort to identify the key residues for Gag assembly within the putative CA-p3 helix, each of the 13 amino acids was mutated (Fig. 2A). With the exceptions of A370 and A371 that were changed to valine, the other 11 amino acids were substituted by alanine in the context of the C3 DNA construct (Fig. 2A). After transfection of these mutated DNA constructs into COS-7 cells, virus particles within the culture fluids were pelleted by ultracentrifugation, and their levels were determined either by Western blot or RT assays. The results of Fig. 2B show that mutations K364A and M365A led to a marked decrease in virus production in comparison to C3 and that mutations L368A and M372A virtually eliminated virus generation. Defective virus production was also observed for these four mutations upon transfection of HeLa cells (data not shown).

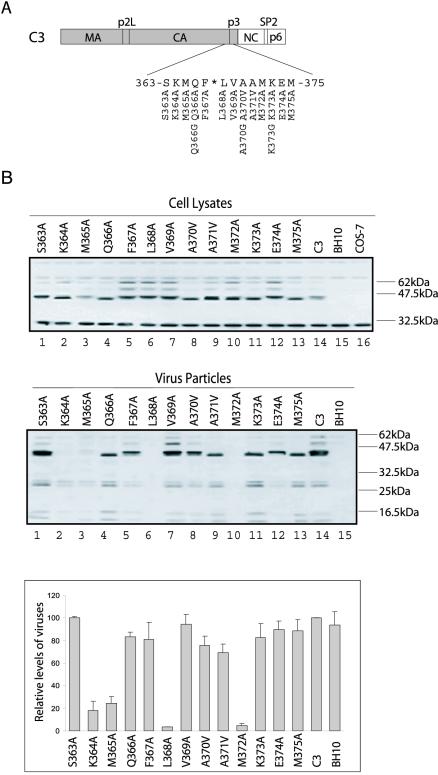

FIG. 2.

Characterization of the CA-p3 boundary region for residues involved in virus production. (A) Substitution of the CA-p3 residues spanning positions 363 to 375. (B) Effects of the various mutations on virus production. Viral protein expression within transfected COS-7 cells was analyzed by Western blot with rabbit anti-BIV serum. Virus particles within the culture fluids were pelleted by ultracentrifugation, and their levels were determined by both Western blot and RT assays. RT levels of the C3 viruses were arbitrarily set at 100, and the results are the average of three independent transfection experiments.

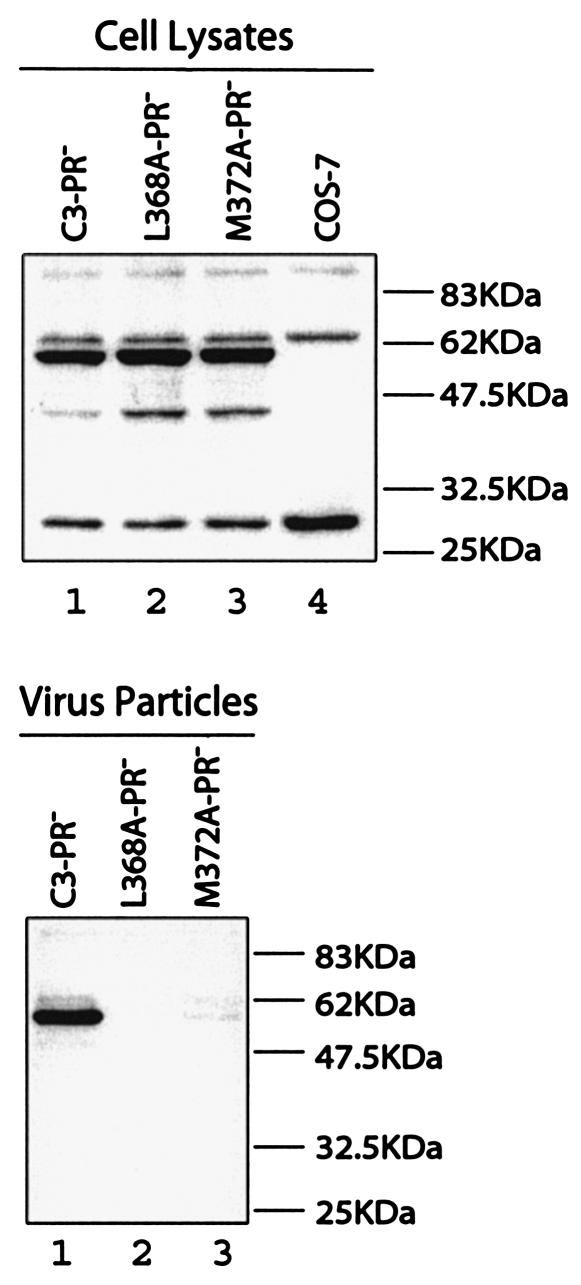

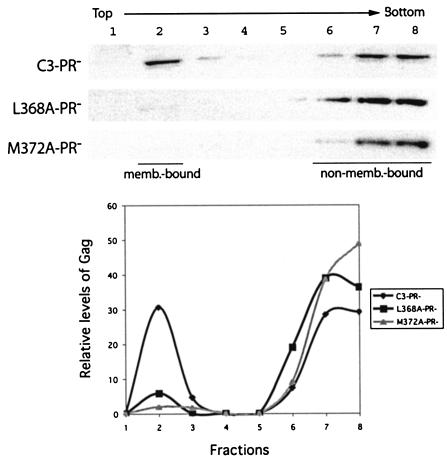

The adverse effects of L368A and M372A on virus production were further evaluated in the context of a protease negative mutation termed D25A that altered the active site of HIV-1 protease (29). Again, drastically low levels of virus particles were made by the L368A-PR− and M372A-PR− DNA constructs in comparison to C3-PR− (Fig. 3). This indicates that incomplete processing of the chimeric Gag proteins by HIV-1 protease (as shown by the results in Fig. 2B) did not cause the defective virus production observed for the L368A and M372A mutations.

FIG. 3.

Effects of the L368A and M372A mutations on virus production in the context of an HIV-1 protease mutation D25A. Viral proteins that were expressed within COS-7 cells or associated with released virus particles were assessed by Western blot with rabbit anti-BIV serum.

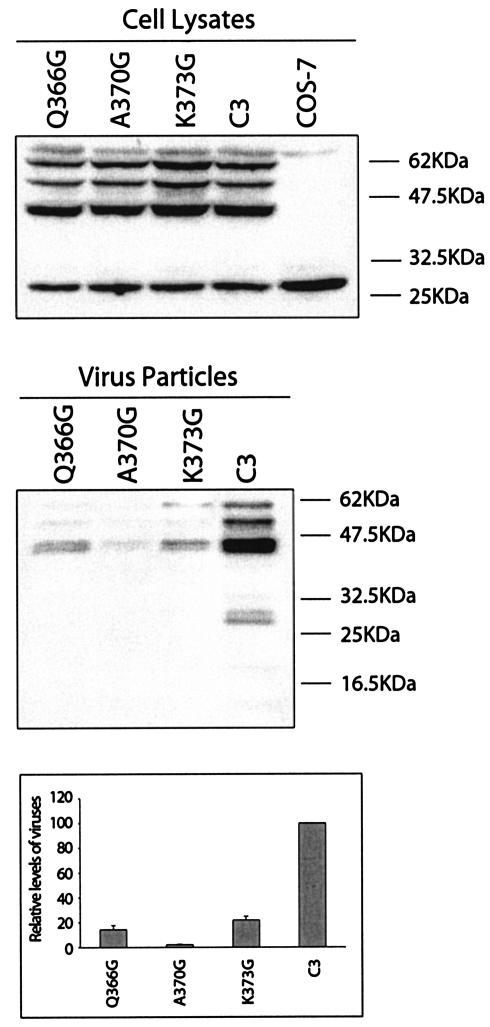

On the basis of these mutagenesis data, we proceeded to test whether the helical nature of this CA-p3 boundary region was required for Gag assembly. Toward this end, each of the amino acids Q366, A370, and K373 was changed to glycine such that the helix can be disrupted (Fig. 2A). The results of transfection experiments showed that all three mutations Q366G, A370G, and K373G led to substantial decreases in virus production (Fig. 4), as opposed to the high yield of virus particles when the relevant amino acids were changed to other types, such as mutations Q366A, A370V, and K373A (as shown by the results in Fig. 2B). Thus, disruption of the putative CA-p3 helical structure by insertion of a glycine residue results in defective Gag assembly.

FIG. 4.

Insertion of glycine into the putative CA-p3 helical region restricts virus production. The Q366G, A370G, and K373G mutations were illustrated in Fig. 2A. Viral protein expression within cells and levels of extracellular particles were examined by Western blot and RT assays as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

A LAEAL motif is able to support efficient virus production in the place of the BIV p3 region.

The two key residues, L368 and M372, identified above are separated by three amino acids 369-VAA-371 (Fig. 1A). Incidentally, the HIV-1 CA-SP1 boundary region also contains the same two residues within a pentapeptide motif LAEAM (Fig. 1A) and, more importantly, they were recently shown to be essential for HIV-1 production (25). However, it was noted that, in contrast to the BIV LVAAM sequence that is entirely located within BIV p3, HIV-1 SP1 itself only contains the AEAM portion of the LAEAM motif (Fig. 5A). As a consequence, a simple replacement of the BIV p3 region with the HIV-1 SP1 sequence in construct C2 failed to recreate the complete LAEAM motif (Fig. 1A), which may explain the inability of C2 to produce virus particles. To test this possibility, we inserted a leucine at the N terminus of SP1 in the C2 construct to restore the LAEAM motif. The DNA clone thus generated was termed C2L (Fig. 5B). Analysis of virus particles by Western blot revealed weak but positive signals for C2L (Fig. 5C, lane 4). This low yield of virus particles was further verified by data from RT assays which indicated that the levels of RT activity associated with the C2L particles were ∼10-fold higher than those for C2, albeit still ∼12-fold lower in comparison to C3 (Fig. 5C). Therefore, restoration of a complete LAEAM motif in C2L did lead to a significant increase in virus production.

FIG. 5.

Efficient virus production after replacement of the BIV p3 sequence by the short motifs LAQAL, LAEAL, and LAKAL. (A) Illustration of the CA-NC boundary region for HIV-1, BIV, visna virus, FIV, and EIAV. The CA-NC spacer sequences are indicated in boldface. The predicted α-helices are underlined. The asterisks indicate the sites cleaved by the viral protease. (B) Replacement of the BIV p3 region by heterogeneous sequences. The CA-NC spacer sequences in the constructs C2L, C2-VQ, C2-FE, and C2-EK are derived from HIV-1, visna virus, FIV, and EIAV, respectively. The inserted sequences are highlighted in boldface. (C) Virus production by the C2L, C2-VQ, C2-FE, and C2-EK DNA constructs after transfection of COS-7 cells. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot with rabbit anti-BIV serum. Virus particles in the culture fluids were assessed either by RT assays or by Western blot with rabbit anti-HIV-1 NC serum.

The CA-NC spacers in the cases of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and EIAV consist of nine and five amino acids, respectively (5, 15). These spacers contain the motifs LAEAL and LAKAL that are analogous to those seen with HIV-1 and BIV (Fig. 5A). Gag processing for visna virus has not been well characterized; nonetheless, a LAQAL motif is also present at the boundary of the CA and NC domains (34) (Fig. 5A). It is also noted that each of these three short motifs resides in a helical structure, based on the results of computer modeling (Fig. 5A) (33). Considering the importance of the CA-NC spacer in the assembly of HIV-1 and BIV, it is likely that these short motifs may also regulate the production of the relevant viruses, an issue that still needs to be validated. Regardless of this uncertainty, conservation of the pentapeptide modules within the CA-NC spacer from different types of lentiviruses prompted us to test whether the LAQAL, LAEAL, and LAKAL motifs could support virus production when they were inserted in the place of the BIV p3 region. Toward this end, three DNA constructs were generated, namely, C2-VQ, C2-FE, and C2-EK which contained the LAQAL, LAEAL, and LAKAL motifs, respectively (Fig. 5B). Upon transfection of COS-7 cells, each of these three constructs was able to generate high levels of virus particles (Fig. 5B), with C2-FE showing the highest efficiency in this regard. Therefore, the BIV p3 region can be functionally replaced by CA-NC spacer sequences derived from nonprimate lentiviruses such as FIV, EIAV, and visna virus.

The L368A and M372A mutations block association of Gag with the plasma membrane.

Gag proteins assemble on the plasma membrane where virus particles are eventually made. In this context, we speculated that the L368A and M372A mutations might have diminished the affinity of Gag for the plasma membrane either in a direct or an indirect manner, and thus inhibited virus production. To test this possibility, we first centrifuged the cell-associated Gag complexes at 100,000 × g for 1 h and then assessed the pelletable materials for membrane-bound Gag by performing the membrane flotation assay. The results showed that >30% of the C3 Gag proteins were associated with the cellular membranes (Fig. 6). In contrast, <5% of the L368A and M372A mutated Gag molecules were membrane bound (Fig. 6). Therefore, the L368A and M372A mutations severely reduced the affinity of Gag for the cellular membranes.

FIG. 6.

The L368A and M372A mutations disrupt the association of Gag with cellular membranes. Cell homogenates were first centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h, and the pelletable (P100) materials were subjected to membrane flotation assays as described previously (24). Eight fractions were collected for each gradient, and the cellular membranes as well as membrane-associated materials were collected within fraction 2. Viral Gag proteins were detected by Western blot with rabbit anti-BIV serum. Relative levels of Gag proteins in each fraction were determined through use of the NIH Image program, and the results are shown in the graph.

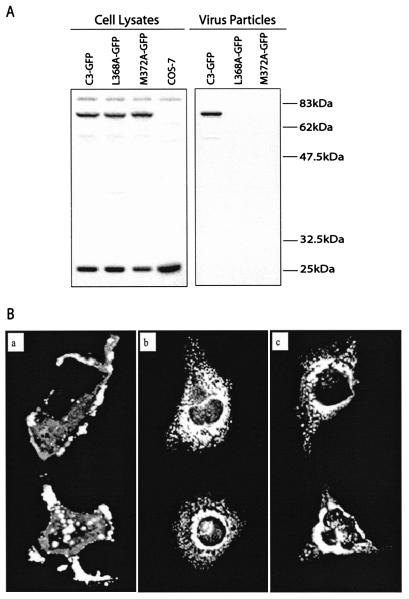

Since the L368A and M372A mutated Gag molecules were for the most part not membrane associated, we expected that they might display aberrant subcellular distribution in comparison to the C3 Gag that was able to efficiently produce virus particles. Toward this end, the EGFP protein was attached to the C terminus of Gag such that the Gag proteins could be visualized within cells by using confocal microscopy. In the first place, the results of Western blot demonstrated that appending EGFP to Gag did not alter the assembly phenotypes of the relevant Gag proteins, i.e., in contrast to the efficient virus production by C3-GFP, the L368A-GFP and M372A-GFP fusion proteins barely generated any virus particle (Fig. 7A). When the Gag proteins were visualized by using confocal microscopy, the C3-GFP fusion proteins were mostly seen at the periphery of the cells in a punctate state (Fig. 7Ba); in contrast, L368A-GFP and M372A-GFP were mainly located within the cytoplasm (Fig. 7Bb and c). These distinct phenotypes were constantly observed under the confocal microscope, and images of two cells are shown as examples for each type of virus (Fig. 7B). Therefore, the L368A and M372A mutations must have restricted the migration of Gag to the plasma membrane, where virus particles should normally assemble. Notably, a large proportion of the L368A-GFP and M372A-GFP molecules were located around the nucleus (Fig. 7Bb and c), this suggests that these mutated Gag proteins may have been retargeted to cellular membranes, such as the endoplasmic reticulum, where virus particles might have been formed. However, electron-dense virus-like particles were not seen under EM in cells that had been transfected by either the L368A or M372A DNA (data not shown). Therefore, the L368A and M372A mutated Gag proteins were retained within the cytoplasm and thus were unable to generate virus particles on the plasma membrane.

FIG. 7.

Subcellular localization of the mutated Gag proteins. (A) Virus production by the C3-GFP, L368A-GFP, and M372A-GFP DNA constructs. Western blot was performed with rabbit anti-BIV serum. (B) Visualization of the Gag-GFP fusion proteins by using confocal microscopy. Subpanels: a, C3-GFP; b, L368A-GFP; c, M372A-GFP.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated here the important role of the CA-NC spacer p3 in the assembly of BIV Gag. This result further supports the hypothesis that proper assembly of lentiviral Gag proteins requires the CA-NC spacer sequence (1). Lentiviruses can be divided into two groups: primate and nonprimate lentiviruses. The first group includes HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIV. The CA-NC spacer SP1 has been shown to be indispensable for HIV-1 assembly (1, 22, 28), and this function of SP1 can also be well performed by an equivalent spacer from the HIV-2 Gag (18). Although the importance of the CA-NC spacer in the assembly of HIV-2 and SIV has not yet been directly addressed, a similar function may exist, since the CA-NC spacer sequences of primate lentiviruses are highly conserved at the N-terminal region (23) and, more importantly, these conserved residues represent the major determinants within SP1 for HIV-1 production (1, 25). In terms of the nonprimate lentiviruses, a potential involvement of the CA-NC spacer sequences in the assembly of EIAV and FIV is implicated by two lines of evidence. First, these two spacers contain pentapeptide motifs that are homologous to those identified in BIV, as well as in HIV-1 (Fig. 5A). Second, they were able to functionally replace the BIV p3 sequence to support virus production (Fig. 5). In addition to their importance in the assembly of the relevant lentiviral Gag proteins, the mechanisms underlying this activity of the CA-NC spacers may differ between the primate and nonprimate lentiviruses, since the assembly function of the p3 region in the context of BIV CA could not be performed by the HIV-1 SP1 sequence (Fig. 1).

The RSV Gag protein also contains a spacer between the CA and NC domains; however, removal of this spacer sequence still allowed efficient virus production, even though the mutated viruses thus made were virtually noninfectious (4). Thus, in contrast to the essential role for the CA-NC spacer in the assembly of HIV-1 and BIV, the equivalent spacer is not needed for assembly or release of RSV. This suggests that different types of retroviral Gag proteins may use distinct mechanisms for their assembly, which is likely reflected by structural differences within the virus particles thus generated. For instance, the core structures within the mature lentivirus particles, such as HIV (38), SIV (6), and EIAV (32), are elongated and conical in shape; in contrast, the mature particles of RSV (21), as well as other mammalian oncogenic viruses, such as murine leukemia virus (45) and mouse mammary tumor virus (36), carry essentially isometric cores.

Principles for the assembly activity of the lentiviral CA-NC spacer are still poorly understood. Conceivably, these spacer sequences may serve as the binding site for a cellular factor(s) or interact with the other portions of Gag. Elucidation of this latter possibility is hampered by the lack of a high-resolution structure for this region. Structures of the CA proteins have been resolved for a few retroviruses, including HIV-1 (3, 8-10, 27, 42), EIAV (17), human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (19), and RSV (20); however, the extreme C-terminal amino acid residues, together with the downstream spacer region, are disordered. Thus, it is fairly difficult to characterize the potential interaction of the CA-NC spacer sequence with the other portions of Gag on the basis of available structural data.

Although the HIV-1 SP1 region has been shown to be disordered within the CA146-231-SP1 molecule (42), this region may assume a rigid structure in the context of the Gag precursor that initiates the assembly of virus particles. Formation of such a putative structure may be facilitated by binding of NC to nucleic acids (such as viral genomic RNA). This event may help to confine the CA-NC boundary region to a restricted space. NC-RNA binding may also exert an effect on the conformation of the upstream Gag sequence, which may then lead to adoption of a regular structure by the SP1 region. In support of these speculations, the results of cryo-EM showed that within the immature HIV-1 particle the CA shell was separated from the inner NC shell by an electron lucent gap of 15Å (7, 13, 40), a distance that is far shorter than if the 11 C-terminal residues of CA and the immediate downstream SP1 region are totally disordered and fully extended, which would account for a space of >95 Å. In light of this information, it is possible that at least a portion of the SP1 sequence assumes an ordered structure in the context of the Gag precursor.

Indeed, the HIV-1 CA-SP1 boundary sequence has been shown to exhibit a high propensity to adopt an α-helix (1). Involvement of this helical structure in HIV-1 assembly has also been indicated by the results of mutagenesis studies (1, 25). Similarly, the BIV CA-p3 boundary region may also assume a helical structure on the basis of the results of computer modeling (Fig. 1A). Potential participation of this latter helix in Gag assembly was indicated by the results of mutagenesis experiments showing that insertion of the glycine residue, instead of alanine or valine, into this CA-p3 helix resulted in severe reductions in virus production (Fig. 4). The helical feature of the HIV-1 CA-SP1 and BIV CA-p3 boundary regions has been further indicated by the results of circular dichroism spectroscopy with synthetic peptides (data not shown); however, the exact folding of these relevant regions in the context of the Gag precursors awaits further structural determination on the basis of experimental data. Resolution of this latter issue will provide a structural basis for better understanding of the CA-NC spacer function in lentiviral Gag assembly.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that, in addition to HIV-1, assembly of BIV Gag also requires the CA-NC spacer sequence. This spacer region may use similar and yet distinct mechanisms to regulate the production of HIV-1 and BIV particles.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark A. Wainberg for valuable discussions. We are grateful to Yunqi Geng and Charles Wood for providing the BIV proviral DNA clone and to Maureen Oliveira for technical assistance.

C.L. is a New Investigator of Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR) and a Research Scholar of the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ). This study was supported by grants from the CIHR, the FRSQ, and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accola, M. A., S. Hoglund, and H. G. Göttlinger. 1998. A putative α-helical structure which overlaps the capsid-p2 boundary in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag precursor is crucial for viral particle assembly. J. Virol. 72:2072-2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accola, M. A., B. Strack, and H. G. Göttlinger. 2000. Efficient particle production by minimal Gag constructs which retain the carboxy-terminal domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid-p2 and a late assembly domain. J. Virol. 74:5395-5402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berthet-Colominas, C., S. Monaco, A. Novelli, G. Sibai, F. Mallet, and S. Cusack. 1999. Head-to-tail dimers and interdomain flexibility revealed by the crystal structure of HIV-1 capsid protein (p24) complexed with a monoclonal antibody Fab. EMBO J. 18:1124-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craven, R. C., A. E. Leure-duPree, C. R. Erdie, C. B. Wilson, and J. W. Wills. 1993. Necessity of the spacer peptide between CA and NC in the Rous sarcoma virus Gag protein. J. Virol. 67:6246-6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elder, J. H., M. Schnölzer, C. S. Hasselkus-Light, M. Henson, D. A. Lerner, T. R. Phillips, P. C. Wagaman, and S. B. H. Kent. 1993. Identification of proteolytic processing sites within the Gag and Pol polyproteins of feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 67:1869-1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukui, T., S. Imura, T. Goto, and M. Nakai. 1993. Inner architecture of human and simian immunodeficiency viruses. Microsc. Res. Tech. 25:335-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuller, S. D., T. Wilk, B. E. Gowen, H. G. Krausslich, and V. M. Vogt. 1997. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals ordered domains in the immature HIV-1 particle. Curr. Biol. 7:729-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamble, T. R., F. F. Vajdos, S. Yoo, D. K. Worthylake, M. Houseweart, W. I. Sundquist, and C. P. Hill. 1996. Crystal structure of human cyclophilin A bound to the amino-terminal domain of HIV-1 capsid. Cell 87:1285-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamble, T. R., S. Yoo, F. F. Vajdos, U. K. von Schwedler, D. K. Worthylake, H. Wang, J. P. McCutcheon, W. I. Sundquist, and C. P. Hill. 1997. Structure of the carboxyl-terminal dimerization domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science 278:849-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gitti, R. K., B. M. Lee, J. Walker, M. F. Summers, S. Yoo, and W. I. Sundquist. 1996. Structure of the amino-terminal core domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science 273:231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonda, M. A., M. J. Braun, S. G. Carter, T. A. Kost, J. W. Bess, L. O. Arthur, Jr., and M. J. Van der Maaten. 1987. Characterization and molecular cloning of a bovine lentivirus related to human immunodeficiency virus. Nature 330:388-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottlinger, H. G., T. Dorfman, J. G. Sodroski, and W. A. Haseltine. 1991. Effect of mutations affecting the p6 gag protein on human immunodeficiency virus particle release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:3195-3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gross, I., H. Hohenberg, T. Wilk, K. Wiegers, M. Grattinger, B. Muller, S. Fuller, and H. G. Krausslich. 2000. A conformational switch controlling HIV-1 morphogenesis. EMBO J. 19:103-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson, L. E., R. E. Benveniste, R. Sowder, T. D. Copeland, A. M. Schultz, and S. Oroszlan. 1988. Molecular characterization of gag proteins from simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVMne). J. Virol. 62:2587-2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henderson, L. E., R. C. Sowder, G. W. Smythers, and S. Oroszlan. 1987. Chemical and immunological characterization of equine infectious anemia virus gag-encoded proteins. J. Virol. 61:1116-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang, M., J. M. Orenstein, M. A. Martin, and E. O. Freed. 1995. p6Gag is required for particle production from full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular clones expressing protease. J. Virol. 69:6810-6818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin, Z., L. Jin, D. L. Peterson, and C. L. Lawson. 1999. Model for lentivirus capsid core assembly based on crystal dimers of EIAV p26. J. Mol. Biol. 286:83-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaye, J. F., and A. M. Lever. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 differ in the predominant mechanism used for selection of genomic RNA for encapsidation. J. Virol. 73:3023-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khorasanizadeh, S., R. Campos-Olivas, and M. F. Summers. 1999. Solution structure of the capsid protein from the human T-cell leukemia virus type-I. J. Mol. Biol. 291:491-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kingston, R. L., T. Fitzon-Ostendorp, E. Z. Eisenmesser, G. W. Schatz, V. M. Vogt, C. B. Post, and M. G. Rossmann. 2000. Structure and self-association of the Rous sarcoma virus capsid protein. Struct. Fold Des. 8:617-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kingston, R. L., N. H. Olson, and V. M. Vogt. 2001. The organization of mature Rous sarcoma virus as studied by cryoelectron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 136:67-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kräusslich, H.-G., M. Facke, A. M. Heuser, J. Konvalinka, and H. Zentgraf. 1995. The spacer peptide between human immunodeficiency virus capsid and nucleocapsid proteins is essential for ordered assembly and viral infectivity. J. Virol. 69:3407-3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuiken, C., B. Foley, et al. 1999. Human retroviruses and AIDS: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N.Mex.

- 24.Liang, C., J. Hu, J. B. Whitney, L. Kleiman, and M. A. Wainberg. 2003. A structurally disordered region at the C terminus of capsid plays essential roles in multimerization and membrane binding of the Gag protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 77:1772-1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang, C., J. Hu, R. S. Russell, A. Roldan, L. Kleiman, and M. A. Wainberg. 2002. Characterization of a putative α-helix across the capsid-SP1 boundary that is critical for the multimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag. J. Virol. 76:11729-11737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang, C., L. Rong, N. Morin, E. Cherry, Y. Huang, L. Kleiman, and M. A. Wainberg. 1997. The roles of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Pol protein and the primer binding site in the placement of primer tRNA(3Lys) onto viral genomic RNA. J. Virol. 71:9075-9086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Momany, C., L. C. Kovari, A. J. Prongay, W. Keller, R. K. Gitti, B. M. Lee, A. E. Gorbalenya, L. Tong, J. McClure, L. S. Ehrlich, M. F. Summers, C. Carter, and M. G. Rossmann. 1996. Crystal structure of dimeric HIV-1 capsid protein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3:763-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morikawa, Y., D. J. Hockley, M. V. Nermut, and I. M. Jones. 2000. Roles of matrix, p2, and N-terminal myristoylation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag assembly. J. Virol. 74:16-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morin, N., E. Cherry, X. Li, and M. A. Wainberg. 1998. Cotransfection of mutated forms of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag-Pol with wild-type constructs can interfere with processing and viral replication. J. Hum. Virol. 1:240-247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parent, L. J., R. P. Bennett, R. C. Craven, T. D. Nelle, N. K. Krishna, J. B. Bowzard, C. B. Wilson, B. A. Puffer, R. C. Montelaro, and J. W. Wills. 1995. Positionally independent and exchangeable late budding functions of the Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus Gag proteins. J. Virol. 69:5455-5460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puffer, B. A., L. J. Parent, J. W. Wills, and R. C. Montelaro. 1997. Equine infectious anemia virus utilizes a YXXL motif within the late assembly domain of the Gag p9 protein. J. Virol. 71:6541-6546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts, M. M., and S. Oroszlan. 1989. The preparation and biochemical characterization of intact capsids of equine infectious anemia virus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 160:486-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rost, B. 1996. PHD: predicting one-dimensional protein structure by profile based neural networks. Methods Enzymol. 266:525-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sonigo, P., M. Alizon, K. Staskus, D. Klatzmann, S. Cole, O. Danos, E. Retzel, P. Tiollais, A. Haase, and S. Wain-Hobson. 1985. Nucleotide sequence of the visna lentivirus: relationship to the AIDS virus. Cell 42:369-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swanstrom, R., and J. W. Wills. 1997. Synthesis, assembly, and processing of viral proteins, p. 263-334. In J. M. Coffin, S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus (ed.), Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 36.Teramoto, Y. A., R. D. Cardiff, and J. K. Lund. 1977. The structure of the mouse mammary tumor virus: isolation and characterization of the core. Virology 77:135-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tobin, G. J., R. C. Sowder II, D. Fabris, M. Y. Hu, J. K. Battles, C. Fenselau, L. E. Henderson, and M. A. Gonda. 1994. Amino acid sequence analysis of the proteolytic cleavage products of the bovine immunodeficiency virus Gag precursor polypeptide. J. Virol. 68:7620-7627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welker, R., H. Hohenberg, U. Tessmer, C. Huckhagel, and H. G. Krausslich. 2000. Biochemical and structural analysis of isolated mature cores of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 74:1168-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiegers, K., G. Rutter, H. Kottler, U. Tessmer, H. Hohenberg, and H.-G. Krausslich. 1998. Sequential steps in human immunodeficiency virus particle maturation revealed by alterations of individual Gag polyprotein cleavage sites. J. Virol. 72:2846-2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilk, T., I. Gross, B. E. Gowen, T. Rutten, F. de Haas, R. Welker, H. G. Krausslich, P. Boulanger, and S. D. Fuller. 2001. Organization of immature human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:759-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wills, J. W., C. E. Cameron, C. B. Wilson, Y. Xiang, R. P. Bennett, and J. Leis. 1994. An assembly domain of the Rous sarcoma virus Gag protein required late in budding. J. Virol. 68:6605-6618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Worthylake, D. K., H. Wang, S. Yoo, W. I. Sundquist, and C. P. Hill. 1999. Structures of the HIV-1 capsid protein dimerization domain at 2.6 Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55:85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiang, Y., C. E. Cameron, J. W. Wills, and J. Leis. 1996. Fine mapping and characterization of the Rous sarcoma virus Pr76Gag late assembly domain. J. Virol. 70:5695-5700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yasuda, J., and E. Hunter. 1998. A proline-rich motif (PPPY) in the Gag polyprotein of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus plays a maturation-independent role in virion release. J. Virol. 72:4095-4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeager, M., E. M. Wilson-Kubalek, S. G. Weiner, P. O. Brown, and A. Rein. 1998. Supramolecular organization of immature and mature murine leukemia virus revealed by electron cryo-microscopy: implications for retroviral assembly mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7299-7304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan, B., S. Campbell, E. Bacharach, A. Rein, and S. P. Goff. 2000. Infectivity of Moloney murine leukemia virus defective in late assembly events is restored by late assembly domains of other retroviruses. J. Virol. 74:7250-7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan, B., X. Li, and S. P. Goff. 1999. Mutations altering the Moloney murine leukemia virus p12 Gag protein affect virion production and early events of the virus life cycle. EMBO J. 18:4700-4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, Y., and E. Barklis. 1997. Effects of nucleocapsid mutations on human immunodeficiency virus assembly and RNA encapsidation. J. Virol. 71:6765-6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, Y., H. Qian, Z. Love, and E. Barklis. 1998. Analysis of the assembly function of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein nucleocapsid domain. J. Virol. 72:1782-1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]