Abstract

Conjoint bicondylar Hoffa fracture is an extremely rare injury. Only one case has been reported previously in the pediatric age group. We describe this injury in a 17-year-old male who presented following a fall with direct impact on his semiflexed right knee. Plain radiographs were inadequate to define the exact pattern of injury. Computed tomographic (CT) scans demonstrated the coronal fracture involving both the femoral condyles which were joined by a bridge of intact bone. The patient was treated with open reduction and internal fixation using swashbuckler (modified anterior) approach. Union occurred within 3 months and at final followup (at 18 months) the patient had a good clinical outcome. The possible mechanism of injury is discussed.

Keywords: Bicondylar Hoffa fracture, classification, conjoint, swashbuckler approach

INTRODUCTION

Coronal shear fracture of the distal femoral condyle is an unusual injury. Albert Hoffa first described this fracture in 1904.1 These fractures usually involve the lateral femoral condyle. Bicondylar Hoffa fracture involving both the femoral condyles is a rare injury and has anecdotally been reported in the literature [Table 1].2,3,4,5,6,7 Most reported cases of bicondylar Hoffa fracture have two separate fracture lines and the two condyles are separated from each other. We describe a rare case of conjoint bicondylar Hoffa fracture where both the femoral condyles were joined by a bridge of intact bone adjacent to the intercondylar notch. To the best of our knowledge, only one case of such an injury has been reported in a child.7

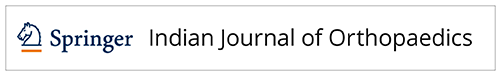

Table 1.

Previously published reports of bicondylar Hoffa fractures

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old male labourer presented to Orthopaedic emergency with the complaint of acute pain and swelling in his right knee following trauma. He had a fall from a 10-m-high ladder with direct impact on his semiflexed right knee. There were no associated injuries and the patient was hemodynamically stable.

Local examination revealed a painful swollen right knee with a 1 cm × 1 cm lacerated wound over the anterior aspect of the knee [Figure 1]. The range of movements were restricted. There was no distal neurovascular deficit or signs of raised compartment pressure. Plain radiographs revealed fracture distal end femur but were inadequate to define the exact fracture pattern [Figure 2]. Noncontrast computed tomographic (CT) scan was performed which established the diagnosis of conjoined bicondylar Hoffa fracture [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Clinical photograph showing a 1cm × 1cm lacerated wound over the anterior aspect of the knee at the point of direct impact

Figure 2.

Plain anteroposterior and lateral radiographs were inadequate to define the exact fracture pattern

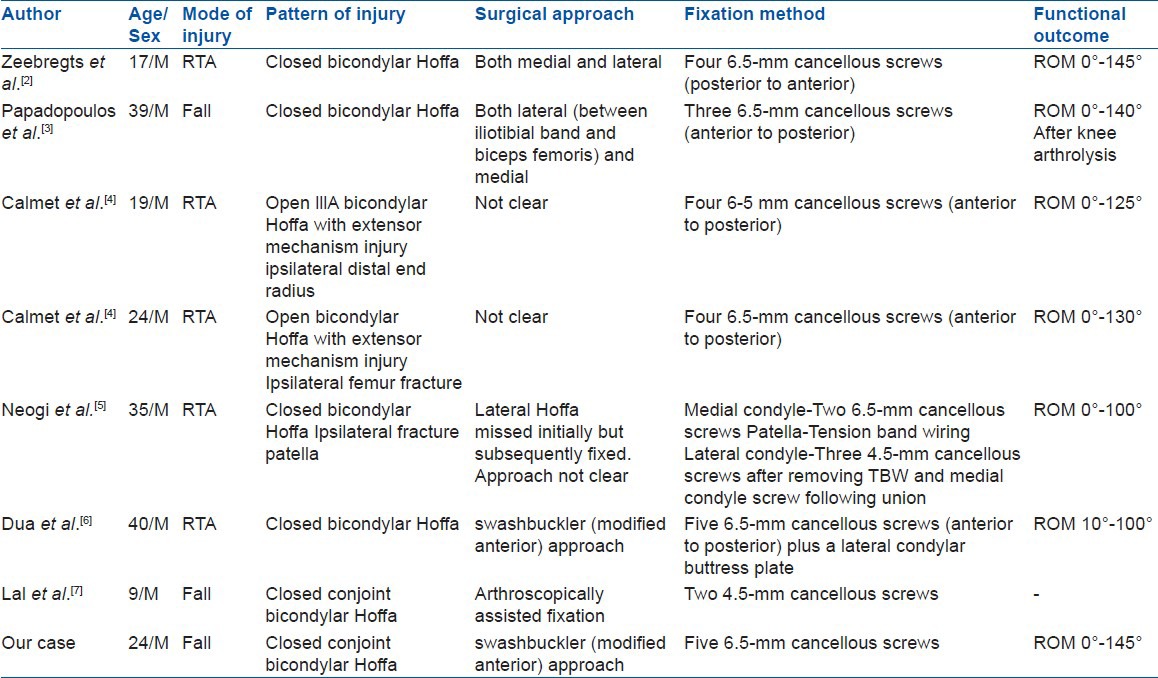

Figure 3.

Axial CT scan cuts showing a bicondylar Hoffa fracture joined by a bridge of intact bone

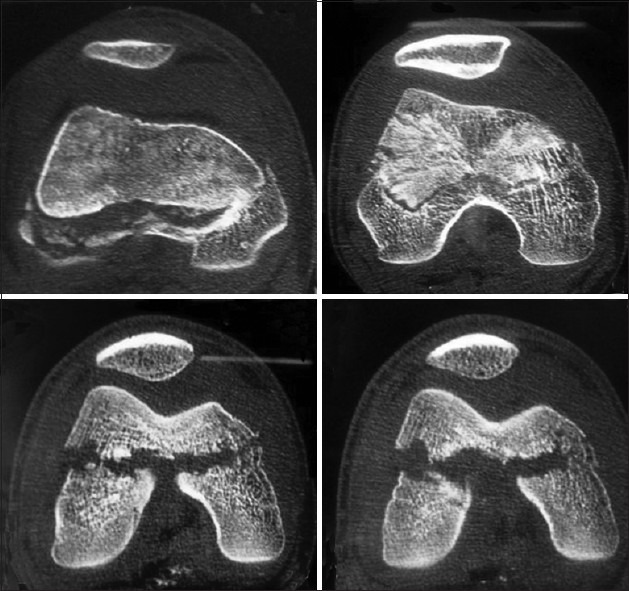

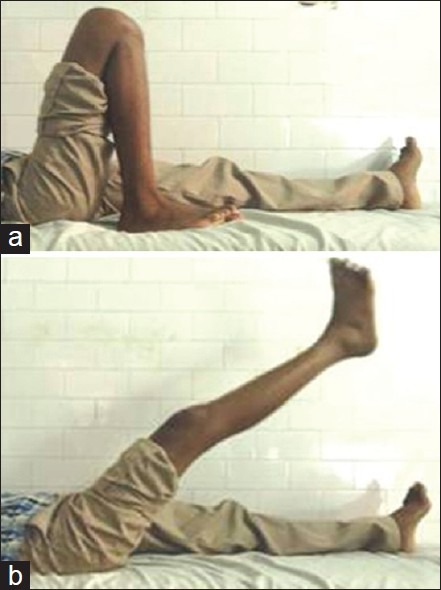

The patient was operated in supine position under tourniquet and regional anesthesia. The lacerated wound was meticulously debrided. The knee joint was then exposed by swashbuckler (modified anterior) approach.8 A lateral parapatellar arthrotomy was done. The vastus lateralis was retracted laterally after lifting it up from the lateral femoral side. The rest of the extensor mechanism along with the patella was retracted medially for unobstructed visualization of both femoral condyles. On exposing the knee, a tangential fracture involving both the femoral condyles was noted [Figure 4]. Both the condyles were joined by a thin bridge of intact bone forming the roof of the intercondylar notch [Figure 4]. Both the cruciate ligaments and menisci were intact. In an attempt to reduce the fracture, the intervening bridge got breached. However, reduction was achieved and five 6.5 mm cannulated cancellous screws were passed from anterior to posterior direction through the nonarticular part under fluoroscopy control. The wound was closed in layers. Post operatively above knee back splint with 30° of knee flexion was applied for 2 weeks. After 2 weeks, intermittent knee mobilization started along with isometric muscle strengthening exercises. Partial weight bearing was started at 6 weeks postoperatively and full weight bearing at 3 months when the fracture had united radiologically. At 18 months, patient had 0°–145° of range of movements without pain and deformity [Figure 5]. He had 10° of extensor lag which was correctable. Radiographs showed no signs of avascular necrosis, osteoarthritis, or implant breakage [Figure 6]. The patient consented for using his data for publication.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative photographs showing the swashbuckler approach (a), pattern of fracture (b), provision reduction (c) and fixation with cannulated cancellous screws (d)

Figure 5.

Clinical photographs at 18 months showing range of motion

Figure 6.

Followup radiographs anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) views at 18 months showing radiological union, without any avascular necrosis, osteoarthritis or implant breakage

DISCUSSION

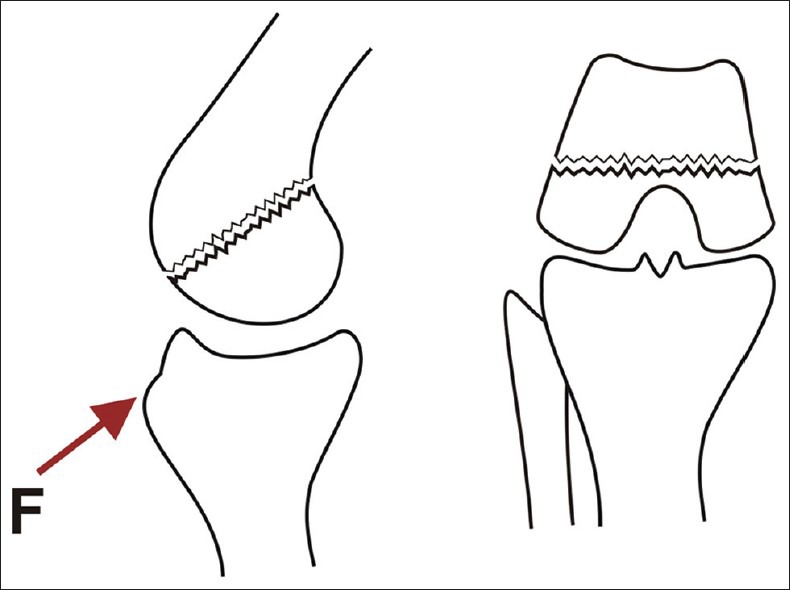

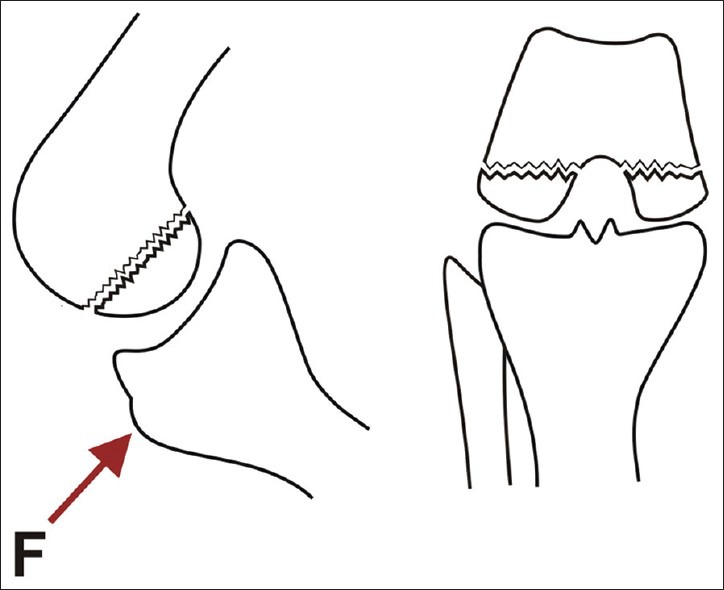

Hoffa fracture usually results from high-velocity trauma following road traffic accidents or fall from height. The specific mechanism of injury that produces Hoffa fracture is not known. Though a shearing force to the posterior femoral condyle has been postulated, both direct impact and vertical shear with twisting mechanisms have also been proposed and a single mechanism is not agreed upon.9 Because of the physiological genu valgum, the lateral femoral condyle is more likely to sustain a direct shearing force, and hence is more likely to get fractured.9 This injury is usually caused when knee is hyperflexed at the time of impact, as during driving motorcycle.9 The exact mechanism of injury of a bicondylar Hoffa fracture has also not been described. We feel that a bicondylar Hoffa fracture occurs when the flexed knee is subjected to a posterior and upward directed force without any varus or valgus component and that the proximity of the fracture line and its obliquity depends upon the degree of knee flexion at the time of impact. The greater the degree of knee flexion, more is the distance of fracture line from the posterior femoral cortex [Figures 7 and 8]. Our patient had sustained an injury following a fall from a 10-m-high ladder with direct impact on his semiflexed right knee, as evident by a small lacerated wound, probably without any varus or valgus component. Therefore, the coronal shear force resulted in a bicondylar Hoffa fracture where both the femoral condyles were joined by a bridge of intact bone adjacent to the intercondylar notch as the fracture line was anterior to the intercondylar notch. Had the knee been flexed more, it would have resulted in a bicondylar Hoffa fracture with two separate fragments with the fracture line being posterior to the intercondylar notch.

Figure 7.

A line diagram showing conjoint bicondylar Hoffa fracture following a posterior and upward directed force (F) in a semiflexed knee

Figure 8.

A line diagram showing nonconjoint bicondylar Hoffa fracture following a posterior and upward directed force (F) in a hyperflexed knee

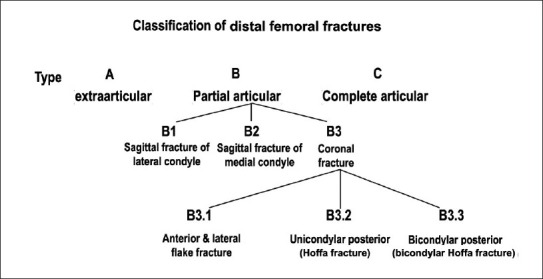

The most widely used classification system developed by Muller, updated by the AO group, and adopted by the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) classifies distal femoral fractures into three groups [Figure 9].10 We feel that B3.3 should be subclassified into two groups: Type B3.3a- Conjoint bicondylar Hoffa fracture where the two condyles are joined by a bride of intact bone and occurs due to a posterior and upward directed force with a semiflexed knee without any varus or valgus [Figure 7]. Type B3.3b- Nonconjoint bicondylar Hoffa fracture where the two condyles are separate from each other and occurs due to posterior and upward directed force with a hyperflexed knee without any varus or valgus [Figure 8]. However, this subclassification needs validation and further evaluation. In view of the rare occurrence of Hoffa, further rarer occurrence of bicondylar Hoffa, and unreported occurrence of conjoint bicondylar Hoffa, validation would be difficult. Similarly, in view of limited information and followup, it is not possible to provide information about the prognosis of this fracture.

Figure 9.

Classification of distal femoral fractures

The diagnosis of Hoffa fracture on plain radiographs can present difficulties because the fracture is obscured in the anteroposterior view by the intact anterior part of the femoral condyle.5 If it is minimally displaced, the fracture may also be difficult to define in the lateral view. If the lateral view is not taken in a standard position, then it is further difficult to interpret whether it is the medial or the lateral condyle that is fractured even if displaced. This may result in the injury being missed on initial imaging.6 Oblique radiographs have an important role both preoperatively and also intraoperatively for evaluation of the reduction, screw length, and condyle identification. However, a CT scan is most helpful not only in defining the fracture pattern but also in deciding the surgical approach. In our case also, the initial radiographs were inadequate to define the exact pattern of the injury. The CT scan demonstrated the bicondylar Hoffa fracture with both fragments joined to each other by a bridge of bone forming the roof of intercondylar notch. It helped us not only in defining the exact nature of the injury but also in the surgical approach. Therefore, like previous authors, we feel a CT scan with 3D reconstruction is the investigation of choice in such patients to define the exact pattern of the fracture and plan the surgical approach.

Treatment of displaced bicondylar Hoffa fracture is essentially surgical. Nonoperative treatment in the form of plaster cast or skeletal traction leads to loss of extension, nonunion, instability, joint contracture, and deformity.2,3,9 Therefore, anatomical reduction of articular surface, stable fixation, and early mobilization should be the aim of treatment.11 For open reduction of bicondylar Hoffa fracture, most authors have used a combined medial and lateral approach. However, we used a swashbuckler (modified anterior) approach as advocated by Dua et al.6 This allowed us to expose the back of femoral condyles on both the sides and facilitated unhindered anatomic reduction of the fracture fragments. The more anterior position of the skin incision as compared to the classical lateral approach allows unobstructed visualization of both the femoral condyles and obviates the need of two incisions. We believe that single incision would result in decreased breach of the quadriceps mechanism, lesser fibrosis, and earlier return of quadriceps strength and range of motion. Lal et al.7 described arthroscopic assisted reduction and fixation for such injuries. However, we believe that it would be technically challenging in a case like ours where the fragment was large and displaced. Although there is no consensus, there is some suggestion that posterior to anterior directed screws may be better.12 However, in our case, the unusual fracture pattern required that we use an approach by which both condyles could be exposed adequately. This we could achieve by swashbuckler (modified anterior) approach. Once the exposure was adequate, the best method was to fix the fractures from anterior to posterior direction under direct vision. Thus, the direction of the screws was determined by the approach required for the fracture exposure.

In conclusion, we described a rare case of a conjoint bicondylar Hoffa fracture managed successfully by open reduction and internal fixation with good clinical outcome at 18 months of followup. We feel that a bicondylar Hoffa fracture occurs when the flexed knee is subjected to a posterior and upward directed force without any varus or valgus component and that the proximity of the fracture line and its obliquity depends upon the degree of knee flexion at the time of impact. CT scan not only helps in defining the exact pattern of injury but also is invaluable in the surgical planning. The Swashbukler (modified anterior) approach allows excellent exposure of both the condyles. Anatomic reduction and rigid internal fixation allows early mobilization and excellent long term outcome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoffa A. Stuttgart: Verlag von Ferdinand Enke; 1904. Lehrbuch der Frakturen und Luxationen; p. 451. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeebregts CJ, Zimmerman KW, Ten Duis HJ. Operative treatment of a unilateral bicondylar fracture of the femur. Acta Chir Belg. 2000;100:1104–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papadopoulos AX, Panagopoulos A, Karageorgos A, Tyllianakis M. Operative treatment of bilateral bicondylar Hoffa fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18:119–22. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200402000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calmet J, Mellado JM, García Forcada IL, Giné J. Open bicondylar Hoffa fracture associated with extensor mechanism injury. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18:323–5. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200405000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neogi DS, Singh S, Yadav CS, Khan SA. Bicondylar Hoffa fracture-a rarely occurring, commonly missed injury. Injury Extra. 2008;39:296–86. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dua A, Shamshery PK. Bicondylar Hoffa Fracture: Open Reduction Internal Fixation Using the swashbuckler approach. J Knee Surg. 2010;23:21–3. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lal H, Bansal P, Khare R, Mittal D. Conjoint bicondylar Hoffa fracture in a child: A rare variant treated by minimally invasive approach. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12:111–4. doi: 10.1007/s10195-011-0133-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Starr AJ, Jones AL, Reinert CM. The “swashbuckler”: A modified anterior approach for fractures of the distal femur. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13:138–40. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199902000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis SL, Pozo JL, Muirhead-Allwood WF. Coronal fractures of the lateral femoral condyle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71:118–20. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B1.2914979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orthopaedic Trauma Association Committee for Coding and Classification. Fractures and dislocations compendium. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10(Suppl 1):41–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer C, Enns P, Alt V, Pavlidis T, Kilian O, Schnettler R. Difficulties involved in the Hoffa fractures. Unfallchirurg. 2004;107:15–21. doi: 10.1007/s00113-003-0697-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarit GJ, Kummer FJ, Gibber MJ, Egol KA. A mechanical evaluation of two fixation methods using cancellous screws for coronal fractures of the lateral condyle of the distal femur (OTA type 33B) J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:273–6. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200604000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]