Abstract

Background

The vagus nerve descends from the brain to the gut during fetal life to reach specific targets in the bowel wall. Vagal sensory axons have been shown to respond to the axon guidance molecule netrin and to its receptor, deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC). As there are regions of the gut wall into which vagal axons do and do not extend, it is likely that a combination of attractive and repellent cues are involved in how vagal axons reach specific targets. We tested the hypothesis that Slit/Robo chemorepulsion can contribute to the restriction of vagal sensory axons to specific targets in the gut wall.

Results

Transcripts encoding Robo1 and Robo2 were expressed in the nodose ganglia throughout development and mRNA encoding the Robo ligands Slit1, Slit2, and Slit3 were all found in the fetal and adult bowel. Slit2 protein was located in the outer gut mesenchyme in regions that partially overlap with the secretion of netrin-1. Neurites extending from explanted nodose ganglia were repelled by Slit2.

Conclusions

These observations suggest that vagal sensory axons are responsive to Slit proteins and are thus repelled by Slits secreted in the gut wall and prevented from reaching inappropriate targets.

Keywords: vagus nerve, nodose ganglion, gastrointestinal tract, axon guidance, enteric nervous system

INTRODUCTION

The vagus nerve descends from the brain to the gut during fetal life to reach specific targets in the bowel wall, including interactions with the enteric nervous system (ENS). A mixed nerve, the vagus nerve contains both sensory and motor fibers; these fibers form the vago-vagal reflexes that coordinate the function of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract (Powley and Phillips, 2002; Browning and Travagli, 2010). The cell bodies of vagal sensory neurons are found primarily in the nodose ganglia, but also in the jugular ganglia (Powley and Phillips, 2002). Once in the bowel wall, vagal sensory axons are found in three different configurations. These configurations have been well-characterized as intramuscular arrays (IMAs) in the external muscle layers, intraganglionic laminar ending (IGLEs) associated with enteric ganglia, and mucosal projections in the lamina propria (Powley and Phillips, 2002; Blackshaw et al., 2007). While the importance of correct pathfinding of vagal fibers within the GI tract is recognized, limited work so far has determined the mechanisms by which vagal endings initially form associations and ultimately interact with the ENS (Ratcliffe et al., 2008, 2011; Murphy and Fox, 2010).

Vagal sensory axons have been shown to respond to axon guidance molecules (Ratcliffe et al., 2006, 2011). Netrin is expressed in the bowel wall and, by acting on its receptor, deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC), mediates the guidance of vagal sensory axons to the developing gut (Ratcliffe et al., 2006). While netrin/DCC may be important in guiding vagal sensory axons to the gut, it remains to be determined how vagal fibers form their well-characterized configurations of IMAs, IGLEs, and mucosal projections in the bowel wall. As there are regions of the gut wall into which vagal axons do and do not extend, it is likely that a combination of attractive and repellent cues are involved in how vagal axons reach specific targets. This concept of attraction/repulsion in the bowel wall is supported by previous work in which netrin-mediated attraction of vagal sensory axons was found to be repelled by the presence of the extracellular matrix molecule, laminin-111 (Ratcliffe et al., 2008). It has been suggested that the formation of IGLEs may occur due to the initial attraction of vagal sensory fibers to netrin-secreting enteric neurons and to the subsequent termination of vagal fibers in the basal lamina that ensheathes enteric ganglia, which is rich in laminin-111 (Ratcliffe et al., 2008, 2011). The netrin/laminin counterpoint, however, is likely to be only one example of the molecular mechanisms by which patterning of the vagal innervation in the bowel wall is formed.

Slit proteins mediate repulsion by acting on roundabout (Robo) receptors. Three Slit glycoproteins (Slit1–3) and four Robo receptors (Robo1–4) have been described in mammals and all appear in alternately spliced isoforms; Slits1–3 have not been shown to have a clear preference for a particular Robo receptor (Ypsilanti et al., 2010). Slit/Robo signaling has been best characterized in the CNS, particularly in the guidance of axons at midline structures (Long et al., 2004). Slit proteins are good candidates to oppose netrin in the gut because they have been shown both to silence netrin in the guidance of CNS axons (Stein and Tessier-Lavigne, 2001) and to be expressed in the fetal bowel (De Bellard et al., 2003).

In the current study, we test the hypothesis that Slit/Robo chemorepulsion can contribute to the restriction of vagal sensory axons to specific targets in the gut wall. We find that transcripts encoding Robo1–2 are present in the nodose ganglia and Slits1–3 are expressed in the bowel. Slit2 protein is secreted in the outer gut mesenchyme and neurites extending from explanted nodose ganglia are repelled by Slit2.

RESULTS

Robo1 and Robo2 Are Expressed in the Fetal and Adult Nodose Ganglion

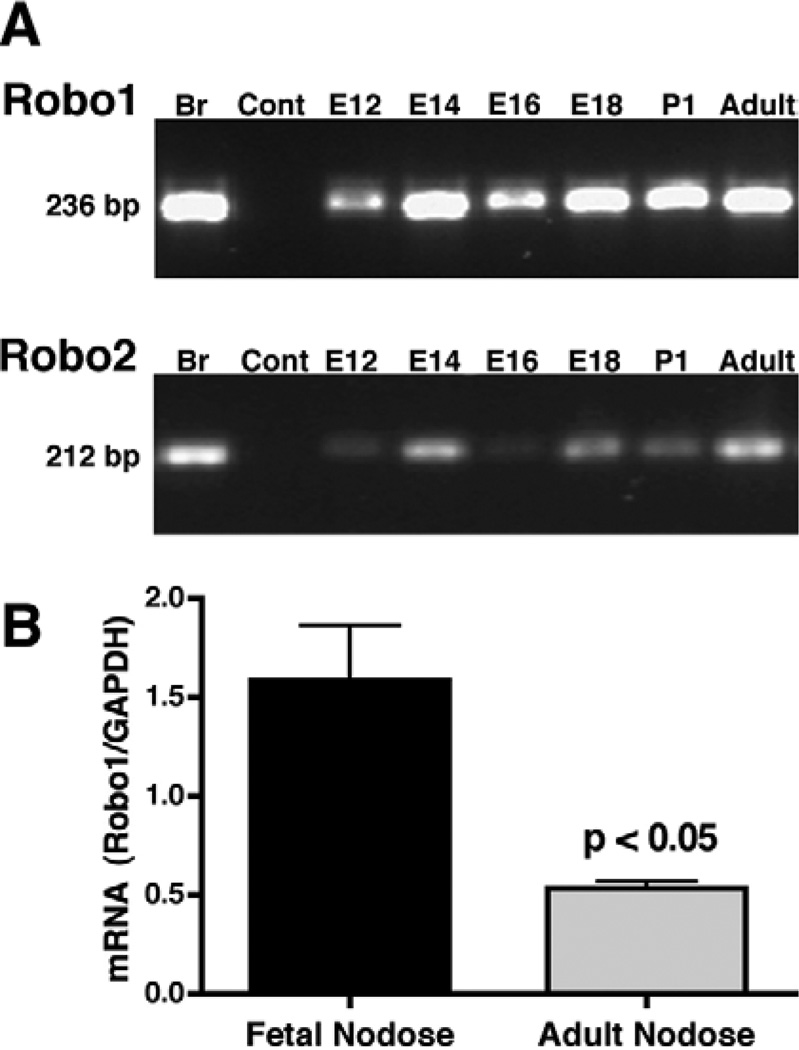

RT-PCR was employed to determine whether transcripts encoding Robo1 and Robo2 could be detected in developing nodose ganglia. E14 brain, which is known to contain Robo1 and Robo2, was used as a positive control (Erskine et al., 2000). Transcripts encoding Robo1 and Robo2 were found in the nodose ganglia at all ages examined (E12 to adult; Fig. 1A). These findings are non-quantitative. No product was detected in controls in which reverse transcriptase was omitted. Transcripts encoding Robo1 were quantified in the nodose ganglia as a function of gestational age using real-time PCR; the expression of Robo1 was greater in fetal (E14 and E18) compared to adult nodose ganglia (P < 0.05; Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

A: Agarose gel. mRNA encoding Robo1 and Robo2 can be found by non-quantitative RT-PCR in the developing (E12–E18), postnatal (P1), and adult nodose ganglia. Brain- (Br) positive control (E14). Water-negative control (Cont). B: Real-time PCR quantitation of transcripts encoding Robo1, normalized to GAPDH. The expression of Robo1 in nodose ganglia is developmentally regulated and is significantly greater during fetal life (E14 and E18) as compared to adulthood (P < 0.05).

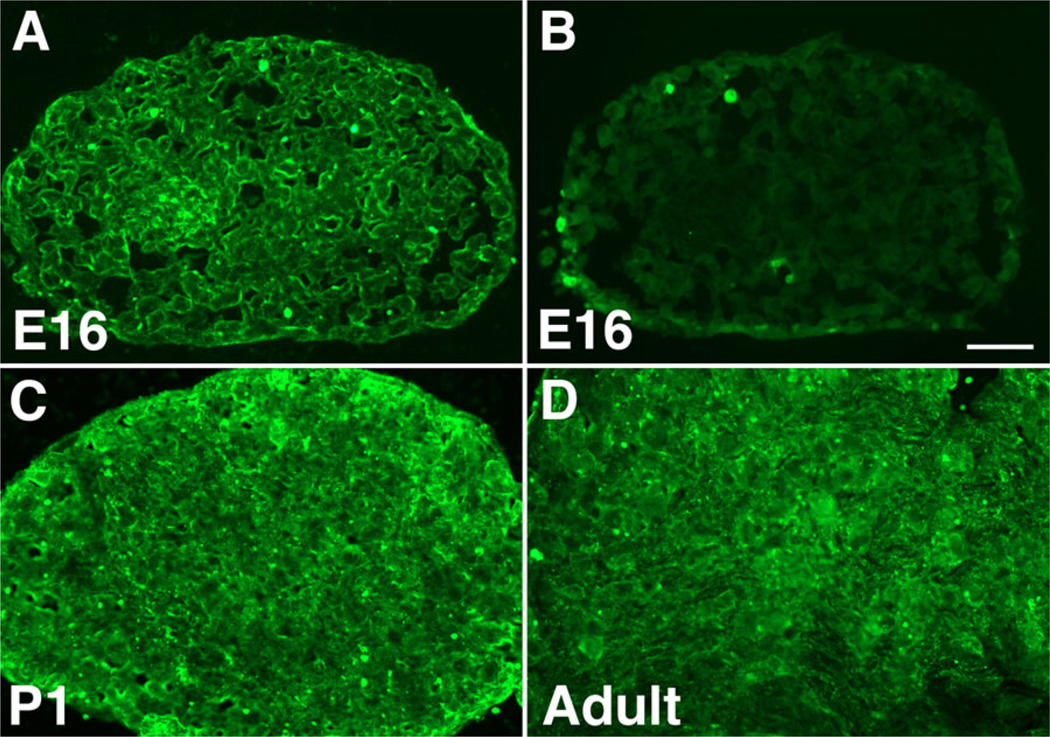

Robo1 immunoreactivity was studied in sections of nodose ganglia in order to verify that Robo1 protein, as well as transcripts, is expressed in nodose neuronal cell bodies. At E16, Robo1 was found in the cytoplasm of a subset of nodose cell bodies (Fig. 2A), with a similar pattern seen at P1 (Fig. 2C) and adult (Fig. 2D) ages. No immunostaining was seen in control preparations in which the primary antibodies were omitted (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Robo1 (green) immunoreactivity is found in fetal and postnatal nodose ganglia. A: E16 nodose. Robo1 immunoreactivity is detected in the cytoplasm of a subset of nodose neuronal cells bodies. B: Negative control. No immunostaining is seen when primary antibodies to Robo1 are omitted. C: P1 nodose. Robo1 immunolabeling appears more diffuse, but remains predominantly cytoplasmic and in a subset of cell bodies. D: A similar pattern is seen in the adult nodose ganglion. Bar = 50 µm.

Slit1, Slit2, and Slit 3 Are Expressed in the Fetal and Adult Gut

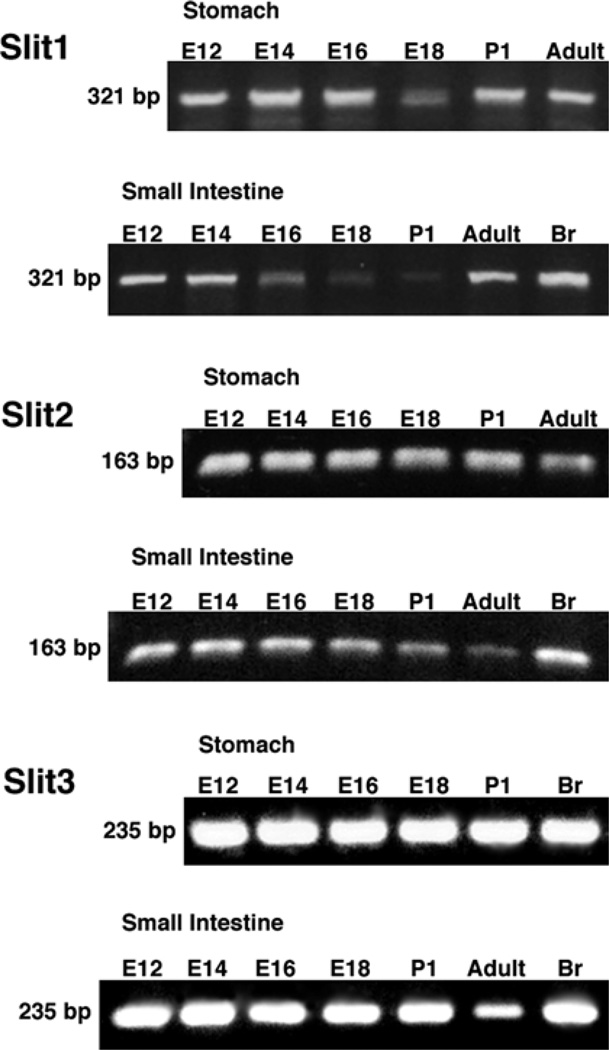

RT-PCR was employed to determine whether transcripts encoding Slit1, Slit2, and Slit3 could be detected in the stomach and small intestine of developing and adult mice. E14 brain, which has been shown to express Slits (Erskine et al., 2000), was investigated as a positive control. Transcripts encoding Slit1, Slit2, and Slit3 were found in the stomach and small bowel at all ages examined (E12 to adult; Fig. 3). These findings are non-quantitative. No product was detected in controls in which reverse transcriptase was omitted.

Fig. 3.

Agarose gel. mRNA encoding Slit1, Slit2, and Slit3 can be found by non-quantitative RT-PCR in the developing (E12–E18), postnatal (P1), and adult nodose ganglia. Brain- (Br) positive control (E14).

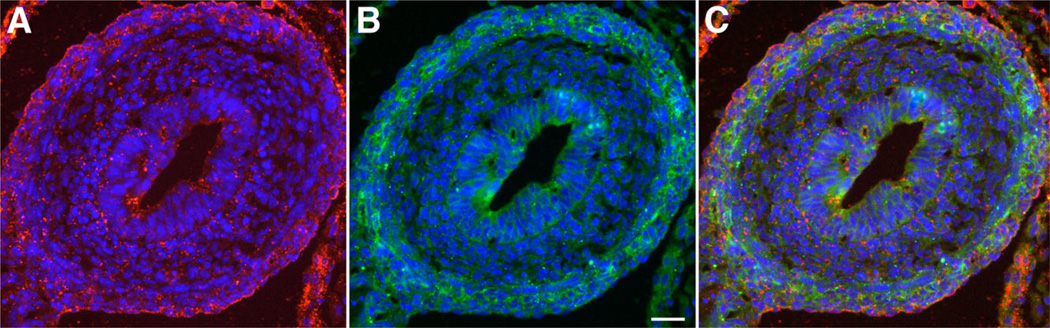

Slit2-immunoreactivity was studied in sections of fetal mice in order to verify that Slit2 protein, as well as transcripts, is expressed in the developing gut wall. At E14, Slit2 was found to be concentrated in the outer gut mesenchyme (Fig. 4A). In order to analyze the pattern of Slit2 secretion in relation to the pattern of netrin-1 distribution, sections of E14 fetal mice were double-labeled with antibodies to Slit2 and netrin-1. The patterns of Slit2 and netrin-1 secretion were found to be similar, but not to completely overlap, with more Slit2 in the outermost mesenchyme and more netrin-1 in the region of the developing myenteric plexus (Fig. 4B and C). No immunostaining was seen in control preparations in which the primary antibodies were omitted (see Supp. Fig. S1, which is available online).

Fig. 4.

Slit2 (red) and netrin-1 (green) immunoreactivities are found in fetal mouse gut at E14. Nuclei are shown with bisbenzimide. A: Slit2 immunoreactivity is concentrated in the outer gut mesenchyme. B: Netrin-1 immunoreactivity is found concentrated in the region of the developing myenteric plexus in the outer gut mesenchyme and in the endoderm of the mucosa. C: Merged image. Slit2 and netrin-1 immunoreactivities are overlapping but not completely coincident in the outer gut mesenchyme. Bar = 25 µm.

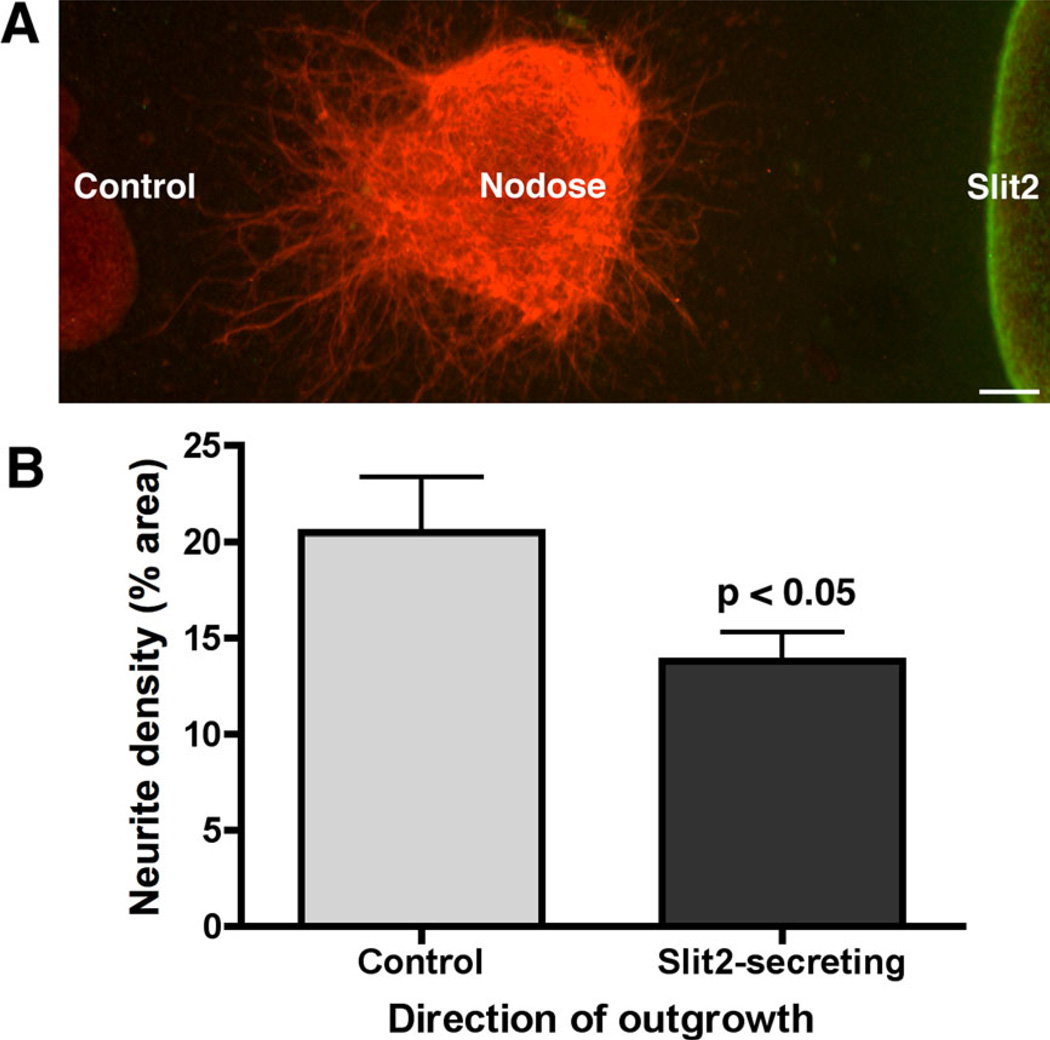

Neurites From Explanted Nodose Ganglia Are Repelled by Co-Cultured Slit2-Secreting Cells

Nodose ganglia were co-cultured with aggregates of stably transfected Slit2-secreting HEK cells and with control non-transfected HEK 293 cells. Aggregates of the two types of cell were arranged on either side of the nodose ganglion in 3-D collagen gels so that the nodose neurites could show preference in growing either to Slit2-secreting or to control cells (n = 19; Fig. 5A). The relative densities of neurites extending toward each were quantified by digitally photographing each immunolabeled culture and then determining the sum of TUJ1-immunoreactive neurites per standardized area with the assistance of Volocity software and customized protocols. The resulting neurite densities, expressed as a percentage per area, were compared using a paired t-test. The density of neurite growth toward the Slit2-secreting cells was less than that toward the control cells (20.5% ± 2.84 SEM vs. 13.8% ± 1.52 SEM; P < 0.05; Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Neurite outgrowth from explants of E14 nodose ganglia are repelled from co-cultured Slit2-secreting cells. A: Aggregates of stably transfected Slit2-secreting (immunolabeled with antibodies to c-Myc; green) and non-transfected control HEK 293 cells were positioned on either side of a co-cultured nodose ganglion (immunolabeled with antibodies to TUJ1; red). Bar = 50 µm. B: The neurite density in a defined region of outgrowth toward Slit2-secreting cells is significantly less than that of an identically defined region of growth toward control cells (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The present study was conducted to test the hypothesis that Slit/Robo chemorepulsion can contribute to the establishment of the vagal sensory innervation of the fetal gut. We find that mRNA encoding Robo1 and Robo2 are expressed in the nodose ganglia throughout development and that Robo1 expression is developmentally regulated. The Robo ligands Slit1, Slit2, and Slit3 are all expressed in the fetal and adult bowel. Slit2 protein is predominantly secreted in the outer gut mesenchyme at E14 in regions that partially overlap with the secretion of netrin-1. Neurites extending from explanted nodose ganglia are repelled by Slit2. These observations suggest that Robo and Slit are expressed by the nodose ganglia and bowel, respectively, during the time period that vagal sensory axons are finding their correct enteric targets and that vagal sensory axons are responsive to secreted Slit proteins.

We have previously demonstrated that DCC is expressed by developing nodose ganglia (Ratcliffe et al., 2006). In the current study, we find that mRNA encoding Robo1 and Robo2 are also expressed by the cell bodies of the nodose ganglia during the same developmental timeline as that described for DCC. The concurrent expression of receptors for classic attractive and repellent guidance molecules is consistent with the idea that both attraction and repulsion are required to steer vagal sensory axons to their correct enteric targets. Axons are known to navigate by changing their responsiveness to alternating attractive and repellent cues. DCC-expressing growth cones of developing spinal axons, for example, are initially attracted to the spinal cord midline; upon reaching midline, Robo is activated in the growth cone and is able to silence attraction to netrin by directly binding to the cytoplasmic domain of DCC (Stein and Tessier-Lavigne, 2001). We propose that a similar “hierarchical silencing” mechanism allows vagal sensory axons to be either attracted by netrins or repelled by Slits, depending on the environment that the axon is crossing.

Robo1 immunoreactivity was found in a subset of neuronal cells bodies in nodose ganglia at fetal and postnatal stages. These observations are not only consistent with our previous work in which DCC-immunoreactive fibers were found to be a subset of the total number of axons in the vagi (Ratcliffe et al., 2006) but is also consistent with the known diversity of vagal projections. Vagal sensory axons not only have extra-intestinal targets, such as in the lung and liver, but form different configurations depending on their location in the gut wall, such as IMAs and IGLEs (Berthoud and Neuhuber, 2000). It is reasonable to expect, therefore, that any individual axon guidance molecule would be expressed by only a subset of nodose neurons at any given time.

We find mRNA encoding Slits1–3 at all ages examined in the fetal and adult gut. Slit2 protein was concentrated in the outer mesenchyme of the fetal bowel at E14. Our observations are consistent with previous work in which transcripts encoding Slit1, Slit2, and Slit3 were found by in situ hybridization to have overlapping expression patterns in the outer wall of the developing chick bowel (De Bellard et al., 2003). Truncal, but not vagal, neural crest–derived cells expressed mRNA encoding Robo1 and Robo2 and were repelled by Slit; the expression of Slits in the outer gut wall thus served to repel Robo-expressing truncal neural crest–derived cells from entering the sub-diaphragmatic bowel (De Bellard et al., 2003). We propose that similar to the repulsion of Robo-expressing truncal neural crest–derived cells, the Slits in the outer gut mesenchyme can also repel Robo-expressing vagal sensory axons.

The hypothesis that Slits can repel vagal sensory axons was supported by the observation that vagal axons do respond to a gradient of Slit secretion. The repellent effect of Slit2 was analyzed in vitro. Nodose ganglia from E14 fetal mice were co-cultured with aggregates of HEK 293 cells transfected to secrete Slit2 and non-transfected control HEK 293 cells. Whereas neurites from nodose ganglia were previously found to be attracted to netrin-1 (Ratcliffe et al., 2008), we found that neurites extending from explanted nodose ganglia were repelled by Slit2.

We compared the patterns of Slit2 and netrin-1 secretion in the fetal bowel and while both were present in the gut wall, Slit2 was more prominent in the outermost mesenchyme and netrin-1 more concentrated in the region of the developing myenteric plexus. The concentration of netrin-1 in the presumptive myenteric plexus is consistent with our previous work, in which we demonstrated that enteric neurons synthesize netrins (Ratcliffe et al., 2011). We hypothesize that the role of Slit2 in the outer gut mesenchyme is to create a zone of repulsion that helps to “herd” vagal fibers toward netrin-1-expressing enteric neurons to form IGLEs, as opposed to being distracted from the remaining netrin in the mesenchyme. This concept of developmentally regulated zones of attraction and repulsion is analogous to that seen in the guidance of retinal ganglion cell axons within the optic tract; expression of Slits in key regions of the diencephalon and telencephalon contribute to confining axonal growth along the correct pathway (Thompson et al., 2006). While we chose to focus our immunolabeling and functional studies on Slit2, we recognize that Slit1, Slit2, and Slit3 may not necessarily be equivalent in their roles (Ypsilanti et al., 2010), thus potentially adding another layer of complexity to how a vagal axon may be directed.

An evolving picture is forming in which the ability of vagal sensory axons to find their correct enteric targets is the end result of a series of attractive and repellent forces. DCC-expressing vagal sensory axons are initially attracted to the netrins secreted in the outer wall of the developing gut (Ratcliffe et al., 2006), then subsequently attracted to the concentration of netrins secreted by enteric ganglia (Ratcliffe et al., 2011). The secretion of Slit2 in a similar region to that of netrin-1 ensures that once vagal sensory axons enter the bowel wall, they are preferentially attracted to the high concentration of netrins synthesized by enteric ganglia rather than by the remaining netrins secreted by the outer gut mesenchyme. Upon reaching the enteric ganglia, vagal sensory axons encounter the laminin sheath that encircles enteric ganglia (Mawe and Gershon, 1989). Laminin converts netrin-mediated attraction to repulsion and the vagal sensory axons stop in the region of laminin and form IGLEs (Ratcliffe et al., 2008). The secretion of Slit2 in the outer gut mesenchyme may also serve to prevent vagal sensory axons from being “stuck” in the outer wall of the gut and encourage vagal sensory axons to grow towards the endoderm. This would be analogous to the ability of Robo to silence the attractive effect of netrin-1, but not its growth-stimulatory effect, in spinal axons once these axons have reached the midline of the spinal cord (Stein and Tessier-Lavigne, 2001). Netrins are not only synthesized by enteric ganglia, but are secreted by mucosal epithelial cells (Jiang et al., 2003; Ratcliffe et al., 2006). As vagal sensory axons penetrate the lamina propria and grow towards the endoderm, they can again become attracted to the netrin gradient secreted by the mucosa. Vagal sensory axons do not penetrate the mucosa, however, because they are stopped by the concentration of laminin found immediately adjacent to the mucosal epithelium and, remaining in the mucosa, form mucosal afferents (Ratcliffe et al., 2008). While the processes above occur in fetal life, we describe continued expression of Slit and Robo into adulthood. It is possible that Slit and Robo contribute to the described postnatal plasticity of vagal axons (Phillips and Powley, 2005), analogous to their role in regeneration after peripheral nerve injury (Yi et al., 2006). Future studies will be required to determine the exact timing and sequence of the above events, as well as to identify additional molecules that may refine the patterning of the vagal sensory innervation of the fetal and postnatal gut.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Timed pregnant mice (CD-1) were obtained from Charles River (Waltham, MA and Saint-Constant, QC). Gestation was dated from the day a vaginal plug was discovered, which was considered E1. When used for experiments, animals were sacrificed by exposure to CO2 gas. The Animal Care and Use Committee of Columbia University and the Animal Research Ethics Board at McMaster University have approved this procedure.

Immunocytochemistry

Nodose ganglia were removed from E16, P1, and adult mice, fixed for 1 hr at 4°C in a solution containing 4% phosphate-buffered formaldehyde (freshly prepared from paraformaldehyde; pH 7.4) and washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4). Whole E14 fetal mice were fixed for 24 hr in 4% formaldehyde and washed in PBS. All tissues were cryoprotected with 30% sucrose, embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT; Tissue-Tek, VWR International, Mississauga, ON), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and cryosectioned at 10 µm. Sections were thaw-mounted onto Colorfrost/Plus microscope slides (VWR).

For immunocytochemisty of both cryosectioned and tissue culture material, tissues were permeabilized and blocked by incubation in PBS containing 0.4% Triton X-100 and 4% normal goat serum or 4% normal horse serum. Primary antibodies were applied overnight in a humidified chamber. These included rabbit antibodies to mouse Robo1 (20 µg/ml; Abcam Inc., Cedarlane, Burlington, ON), goat antibodies to human Slit2 (G-19; 4 µg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), chicken antibodies to mouse/human netrin-1 (1 µg/ml; Aves Labs Inc., Tigard, OR), rabbit antibodies to TUJ1 (0.5 µg/ml; Covance, Montreal, QC), and monoclonal mouse antibodies to c-Myc (9E10; 1 µg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Sites of antibody binding were detected by incubation for 3 hr at room temperature with goat anti-rabbit antibodies labeled with Alexa 488 (1:200; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen Canada Inc., Burlington, ON), donkey anti-goat antibodies labeled with Alexa 488 (1:200; Molecular Probes), and with donkey anti-chicken antibodies labeled with Alexa 594 (1:200; Molecular Probes). For double-labeling of tissue culture material, sites of antibody binding were detected by incubation for 3 hr with goat anti-rabbit antibodies labeled with Alexa 488 (diluted 1:200; Molecular Probes) and goat anti-mouse antibodies labeled with Alexa 594 (diluted 1:200; Molecular Probes). Nuclei were identified by staining DNA with bisbenzimide (1 µg/ml in PBS; Sigma-Aldrich Canada Ltd., Oakville, ON). Labeled tissue sections and cultures were mounted in Vectashield medium (Vector Laboratories Canada Inc., Burlington, ON). Antibodies to Slit2 labeled fixed monolayer preparations of Slit2-secreting HEK 293 cells; no staining was seen when Slit2 antibodies were omitted.

Photomicrographs were obtained with a Retiga Imaging digital camera attached to a Leica DMRXA2 microscope and an Apple computer with Volocity software (Improvision Inc., Montreal, QC). Adobe Photoshop 10.0 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA) was used to merge images and to adjust brightness and contrast.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from mouse nodose ganglia (RNeasy micro kit; QIAGEN Inc., Mississauga, ON) and from gut and brain (homogenization according to manufacturer’s instructions with Trizol; Invitrogen). Brain was investigated as a positive control. Approximately 30–60 nodose ganglia were collected from fetal mice at each age of development (E12 to P1); 20 nodose ganglia were collected from adult mice. Approximately 15 stomachs and small intestines were collected at each age of development (E12–P1); 1 stomach and distal ileum were collected from adult mice. All tissues were combined by developmental age in order to achieve sufficient yield for molecular studies. DNA contamination was removed from gut and brain RNA by incubation with RNase-Free DNase I (Ambion Inc., Applied Biosystems Canada, Streets-ville, ON) for 30 min at 37°C. RNA, from nodose ganglia (1–2 µg), gut (3 µg), or brain (2–3 µg), was then reverse transcribed to cDNA in a 30-µl reaction volume containing random hexamer primers (0.3 µg; Invitrogen), dNTPs (0.5 µM; Promega Corporation, Madison, WI), RNasin (40 U; Promega), and Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV) Reverse Transcriptase (400 U; Invitrogen). Control samples were incubated without M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase.

PCR was used to amplify the resulting cDNA to detect transcripts encoding Robo1, Robo2, Slit1, Slit2, and Slit3. cDNA encoding Robo1 was amplified with primers designed from the GenBank sequence NM_019413 (antisense: 5′-AAGACACTTCCAGTGTTGGA-3′; sense: 5′-AAAACCATCACTCAAGAGGC-3′; amplified product: 236 bp). cDNA encoding Robo2 was amplified with the primers designed to detect the same common region of two known isoforms: GenBank sequences DQ533875.1 (Robo2a) and DQ533876.1 (Robo2b) (antisense: 5′-TTTTACTCCAACCCCTGCAC-3′; sense: 5′-GCATCAGTGTTTCCTGGGAT-3′; amplified product: 212 bp). cDNA encoding Robo1 and Robo2 were amplified for 40 cycles (94°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 45 sec, and 72°C for 45 sec). cDNA encoding Slit1, Slit2, and Slit3 were amplified with the following primers designed from GenBank sequences: Slit1 NM_015748 (antisense: 5′-GCAGTTCCACACCGTTGAGC-3′; sense: 5′-ATGCCATGTAGACAGTAGAG-3′; amplified product: 321 bp), Slit2 NM_178804 (antisense: 5′-TTACGCTGCCTGTCAAAC-3′; sense: 5′-CTTCACCACTTTCTCAACCTC-3′; amplified product: 163 bp) and Slit3 NM_011412 (antisense: 5′-AAGCGAATAGACATCAGCAAG-3′; sense: 5′-CATACAGAGAGAGCAGATTGAG-3′; amplified product: 235 bp). All 3 primers were amplified for 35 cycles. The identities of the Robo1 and Robo2 PCR products were confirmed by sequence analysis (MOBIX Lab, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON). The Slit1, Slit2, and Slit3 PCR products were first subcloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and their identities confirmed by sequencing in an automated capillary electrophoresis system (Applied Biosystems; DNA Analysis and Sequencing Facility, Columbia University, New York, NY).

Real-Time PCR

Real-time PCR was used to quantify transcripts encoding Robo1 in the fetal (E14 and E18) and adult nodose ganglia. cDNA encoding Robo1 was amplified with primers designed from the GenBank sequence NM_019413 (antisense: 5′-GCCAGCAAGGAAGAACAGAC-3′; sense: 5′-GCTTCAATTGGCCTTAGCAG-3′; amplified product: 187 bp) (Huang et al., 2009). The expression of Robo1 was normalized to that of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) using primers designed from the GenBank sequence NM_008084.2 (antisense: 5′-CCATGGAGAAGGCCGGGG-3′; sense: 5′-CAAAGTTGTCATGGATGACC-3′; amplified product: 195 bp). Amplifications were carried out in 20 µl SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Mississauga, ON) and using the CFX96 Thermal Cycler System (Bio-Rad). Conditions were as follows: 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec, 56°C for 5 sec, and 72°C for 10 sec. The threshold cycle was calculated by the software of the instrument (Bio-Rad CFX Manager Software Version 1.6) and relative expression of Robo1 determined using the Pfaffl method (Pfaffl, 2001).

Tissue Culture

Slit2-secreting cells

Control HEK 293 cell (source, ATCC, Manassas, VA) and HEK 293 cells stably transfected with a construct encoding Slit2 protein tagged at the C-terminus with a c-Myc epitope (gift from Dr. Yi Rao, Peking University School of Life Sciences, Beijing, China) (Li et al., 1999) were maintained in a medium consisting of DMEM (GIBCO, Invitrogen Canada Inc., Burlington, ON) supplemented with 0.05% glutamine (GIBCO), 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (GIBCO), 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin (GIBCO), and 200 µg/ml Hygromycin B (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). Transfected, but not control, HEK 293 cells were c-Myc immunoreactive, verifying that the transfected cells expressed the construct. Cell aggregates were prepared as previously described (Ratcliffe et al., 2006).

Co-cultures

Nodose ganglia were dissected from E14 mice and placed into 35-mm Petri dishes in iced Dulbecco’s Minimal Essential Media with F12 (DMEM/F12; GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO), 0.6% D-glucose, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (GIBCO). The ganglia and HEK 293 cell aggregates were then transferred to 4-well chamber slides (Nunc, VWR) for culture in a 3-dimensional collagen gel. Each well contained a small base of collagen (20 µl) pre-polymerized with bicarbonate from a solution of rat tail collagen (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, ON) in 10× Minimal Essential Media (GIBCO). Two layers of collagen, first 2 µl and then 4 µl were sequentially applied over the nodose ganglia and cells. The collagen was allowed to polymerize for 10 min at room temperature after each layer was applied; growth medium was then added and the cultures were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The cultures were maintained for 48 hr and fixed overnight as described above.

Supplementary Material

Key Findings.

Transcripts encoding Robo1 and Robo2 are expressed in developing and adult nodose ganglia.

Transcripts encoding Slit1, Slit2 and Slit3 are expressed in developing and adult gut.

Slit2 protein is located in the outer gut mesenchyme.

Neurites extending from explanted nodose ganglia are repelled by Slit2 in vitro.

Slit/Robo chemorepulsion may contribute to the establishment of the vagal sensory innervation of the fetal gut.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

HEK 293 cells transfected with a construct encoding Slit2 protein were a gift from Dr. Yi Rao (Northwestern University; Peking University School of Life Sciences). We thank Nathan Farrar for his advice. Sources of financial support: J.P. Bickell Foundation and the McMaster Children’s Hospital (E.M.R.).

Grant sponsor: J.P. Bickell Foundation; Grant sponsor: McMaster Children’s Hospital.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- Berthoud HR, Neuhuber WL. Functional and chemical anatomy of the afferent vagal system. Auton Neurosci. 2000;85:1–17. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshaw LA, Brookes SJ, Grundy D, Schemann M. Sensory transmission in the gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning KN, Travagli RA. Plasticity of vagal brainstem circuits in the control of gastric function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:1154–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellard ME, Rao Y, Bronner-Fraser M. Dual function of Slit2 in repulsion and enhanced migration of trunk, but not vagal, neural crest cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:269–279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine L, Williams SE, Brose K, Kidd T, Rachel RA, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M, Mason CA. Retinal ganglion cell axon guidance in the mouse optic chiasm: expression and function of Robos and Slits. J Neurosci. 2000;13:4975–4982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-04975.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Yu W, Li X, Niu L, Li K, Li J. Robo1/robo4: different expression patterns in retinal development. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Liu M, Gershon MD. Netrins and DCC in the guidance of migrating neural crest-derived cells in the developing bowel and pancreas. Dev Biol. 2003;258:364–384. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HS, Chen JH, Wu W, Fagaly T, Zhou L, Yuan W, Dupuis S, Jiang ZH, Nash W, Gick C, Ornitz DM, Wu JY, Rao Y. Vertebrate slit, a secreted ligand for the transmembrane protein round-about, is a repellent for olfactory bulb axons. Cell. 1999;96:807–818. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long H, Sabatier C, Ma L, Plump A, Yuan W, Ornitz DM, Tamada A, Murakami F, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M. Conserved roles for Slit and Robo proteins in midline commissural axon guidance. Neuron. 2004;42:213–223. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawe GM, Gershon MD. Structure, afferent innervation, and transmitter content of ganglia of the guinea pig gallbladder: relationship to the enteric nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1989;283:374–390. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MC, Fox EA. Mice deficient in brain-derived neurotrophic factor have altered development of gastric vagal sensory innervation. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:2934–2951. doi: 10.1002/cne.22372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RJ, Powley TL. Plasticity of vagal afferents at the site of an incision in the wall of the stomach. Auton Neurosci. 2005;123:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powley TL, Phillips RJ. Musings on the wanderer: what’s new in our understanding of vago-vagal reflexes? I. Morphology and topography of vagal afferents innervating the GI tract. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G1217–G1225. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00249.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe EM, Setru SU, Chen JJ, Li ZS, D’Autreaux F, Gershon MD. Netrin/DCC-mediated attraction of vagal sensory axons to the fetal mouse gut. J Comp Neurol. 2006;498:567–580. doi: 10.1002/cne.21027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe EM, D’Autreaux F, Gershon MD. Laminin terminates the Netrin/DCC mediated attraction of vagal sensory axons. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:960–971. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe EM, Fan L, Mohammed TJ, Anderson M, Chalazonitis A, Gershon MD. Enteric neurons synthesize netrins and are essential for the development of the vagal sensory innervation of the fetal gut. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71:362–373. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein E, Tessier-Lavigne M. Hierarchical organization of guidance receptors: silencing of netrin attraction by slit through a Robo/DCC receptor complex. Science. 2001;291:1928–1938. doi: 10.1126/science.1058445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H, Barker D, Camand O, Erskine L. Slits contribute to the guidance of retinal ganglion cell axons in the mammalian optic tract. Dev Biol. 2006;296:476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi XN, Zheng LF, Zhang JW, Zhang LZ, Xu YZ, Luo G, Luo XG. Dynamic changes in Robo2 and Slit1 expression in adult rat dorsal root ganglion and sciatic nerve after peripheral and central axonal injury. Neurosci Res. 2006;56:314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ypsilanti AR, Zagar Y, Chedotal A. Moving away from the midline: new developments for Slit and Robo. Development. 2010;137:1939–1952. doi: 10.1242/dev.044511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.