Summary

Antigen affinity is commonly viewed as the driving force behind the selection for dominant clonotypes that can occur during the T cell-dependent processes of class switch recombination (CSR) and immune maturation. To test this view, we analyzed the variable gene repertoires of natural monoclonal antibodies to the hapten 2-phenyloxazolone (phOx) as well as those generated after phOx protein carrier-induced thymus-dependent or Ficoll-induced thymus independent antigen stimulation. In contrast to expectations, the extent of IgM heterogeneity proved similar and many IgM from these three populations exhibited similar or even greater affinities than the classic Ox1 clonotype that dominates only after CSR among primary and memory IgG. The population of clones that were selected during CSR exhibited a reduced VH/VL repertoire that was enriched for variable domains with shorter and more uniform CDR-H3 lengths and almost completely stripped of variable domains encoded by the large VH1 family. Thus, contrary to the current paradigm, T-cell dependent clonal selection during CSR appeared to select for VH family and CDR-H3 loop content even when the affinity provided by alternative clones exhibited similar to increased affinity for antigen.

Keywords: class switch recombination, clonal selection, repertoire restriction, CDR-H3 lengths, BCR-specific T cells

Introduction

Antibodies, the effector molecules of humoral immunity, are generated as a consequence of B lymphocyte stimulation. The nature of the antigen tends to influence which of the various differentiation pathways is activated.

Natural IgM (but not IgG and IgA) Ab are produced in `antigen-free´ animals [1, 2]. These natural Abs (nAbs) tend to be produced by autonomously `activated´ B1 cells, which predominantly reside in the peritoneal and pleural cavities. These cells produce low affinity Ab for a multitude of autoantigens, including intracellular components (e.g. DNA and nuclear and cytoskeleton proteins) as well as self-antigens found in cell membranes and serum (e.g. Ig and cytokines). Some nAb cross-react with bacterial polysaccharides, proteins and lipids, and thus can be induced by exogenous antigenic stimuli. IgM predominates, but IgA and IgG3 are also produced. NAb often express a restricted V region repertoire and show a high degree of idiotypic connectivity [1, 2].

In contrast to the B1 cell, autonomous activation or self-renewal is not a feature of the conventional B2 cell. Antibody production by B2 cells typically reflects exogenous stimulation by either thymus-independent (TI) or thymus-dependent (TD) Ag. Classic TI Ag can be subdivided into mitogenic TI-1 Ag, with LPS as the prototype, and TI-2 Ag that exhibit repetitive epitopes which allow multimeric binding to and direct activation of the B2 cell. TI-2 Ag include bacterial polysaccharides, synthetic complexes of such carbohydrate carriers or polysucrose (Ficoll) with low molecular weight haptens like 2-phenyloxazolone (phOx) [3] and certain polymerized proteins. Despite the T cell-independence of the direct activation of the B cell, the response to TI-2 Ag is influenced in various ways by T cells. For example, CD4+ TH cells promote the switch from IgM to other isotypes [4] while suppressor/regulatory T cells are able to suppress the overall response and may restrict the response to IgM [5].

Classic TD responses require a series of complex cellular interactions between B cells and T cells and other APC. These interactions are mediated by a multitude of cellular co-stimulatory molecules and secreted cytokines. Shortly after immunization, the TD response starts at the edge of the T cell zone of the white pulp when antigen-binding B cells appear in the outer region of the periarteriolar lymphoid sheath (PALS). The Ag-dependent interaction of T and B cells leads to the development and enlargement of extra-follicular antibody-producing foci at the edge of the PALS and formation of germinal centers in follicles. Both pathways contribute to Ab production during the first 12 days of the primary response [6–10].

A number of B2 responses to exogenous Ag are heavily enriched for use of dominant clonotypes and a selected set of VH/VL genes. These restrictions tend to be genetically based, often strain-specific and include responses to protein-coupled haptens such as azophenylarsonate, phOx, (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl (NP), phosphorylcholine, DNP or phosphatidylcholine; responses to carbohydrates such as dextran and galactan; and responses to some protein Ags [11].

In order to test the extent to which the restricted repertoire generated by TD responses reflects an initial repertoire bias versus affinity-dependent clonal selection, we compared V region sequences of phOx-reactive natural and TI-2- and TD-induced mAb. The primary TD-induced IgM repertoire proved just as heterogeneous as that of natural and TI-2-induced Ab. A genetic restriction of the TD response was not observed until after class switch recombination (CSR) to IgG. The restriction in VH/VL gene use was accompanied by a focusing of the lengths of the 3rd CDR of the heavy chain (CDR-H3). The population of CDR-H3 intervals was of heterogeneous length among the IgM antibodies, but of shorter and more homogeneous in IgG. Moreover, the natural, TI-2- and TD-induced IgM repertoires all contained considerable proportions of Ab with similar or even higher affinity than Ox1 idiotypic (IdOx1) Ab, which among the primary TD IgG response have highest affinity and first dominate that response. Finally, Ab encoded by VH1 family genes were frequently used by IgM, but almost absent among IgG anti-phOx. Collectively, these findings led us to conclude that clonal regulation of T-dependent CSR is heavily influenced by the sequence content of the BCR, including both VH family and CDR-H3.

Results

Heterogeneity of natural anti-2-phenyloxazolone antibodies

Because murine pre-immune sera contain considerable amounts of phOx-reactive Ab [12] and the dominant NPb Id of the TD anti-NP response is also observed among natural Ig [13], we asked how exogenous Ag-induced anti-phOx Ab with the dominant IdOx1 relate to their naturally occurring counterparts by comparing the genetic repertoires of both Ab populations. Although nAb-producing B1 cells mainly reside in the peritoneal cavity, anti-phOx activity could not be detected in five separate fusions of peritoneal cells, each with substantial cell growth. However, in 14 out of 27 successful fusions of spleen cells from non-immunized mice, one to seven exclusively IgM-anti-phOx-secreting hybridomas were obtained from single mice (Table 1). Since nAb predominantly react with a variety of evolutionarily conserved autoantigens [14] and cross-react with exogenous Ag, the anti-phOx nAbs were also tested for reactivity with actin, myosin, dsDNA, tubulin and keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) (Supporting Information Table 1; Table 1). Four nAb appeared to be phOx-`specific´ within the panel of Ag tested, while another (nat11) showed an as strong reaction for both phOx and dsDNA. The remaining nAbs showed unique combinations of multiple reactivities.

Table 1.

VH/VL gene combinations of natural IgM anti-phOx antibodies

| mAb nata |

Fusb | Ag Specc |

rel. Affd |

VH chain genes | VL chain genes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fame | Clf | IGHVg | CDR3-H3h | D | J | Fame | Clf | IGKVg | CDR-L3h | J | ||||

| 01 | 3 | po | n.d. | 1 | 2 | 690 | C_ARSSYYYGSSHADY | FL16.1 | 2 | 4/5 | 1 | 050 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 02 | 7 | po | ~ 1 | 1 | 1 | 668 | C_ASNYFDY | n.f. | 2 | 4/5 | 1 | 143 | C_QQRSSPRTF | 1 |

| 03 | 8 | mo | ~ 0.1 | 1 | 2 | 643j | C_AGYGNYGFFY | SP2.5,7 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 097 | C_WQGTHFPxTF | 2 |

| 04 | 2 | pol | n.d. | 1 | 2 | 627 | C_ARVTTVVARGYAMDY | FL16.1 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 157 | C_QQWSSKPLTF | 5 |

| 05 | 1 | n.d. | ~ 0.1 | 1 | 2 | 627 | C_ARDYGIYYYAMDY | SP2.5,7 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 189 | C_QQSYPWTF | 1 |

| 06 | 9 | n.d. | ~ 0.1 | 1 | 2 | 588 | C_ARWVIWYPFYAMDY | SP2.5,7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 097 | C_WQGTHFPGTF | 1 |

| 07 | 9 | n.d. | ~ 0.1 | 1 | 2 | 510j | C_ARGDYYAMDY | n.f. | 4 | 23 | 1 | 168 | C_QQSNSWPTTF | 5 |

| 08 | 14 | n.d. | ~ 1 | 1 | 3 | 398 | C_ATGYRYDRVWFAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 188 | C_QNDYSYPTWTF | 1 |

| 09 | 4 | n.d. | ~ 0.1 | 1 | 3 | 286 | C_ARRARATGAMDY | ST4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 097 | C_WQGTHFPQTF | 1 |

| 10 | 6 | po | n.d. | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 19/28 | 1 | 175 | C_QQYSSYPLTF | 2 |

| 11 | 10 | bi | ~ 14 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDYYGSRAWFAY | FL16.1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 115 | C_FQGSHVPYTF | 2 |

| 12 | 10 | mo | ~ 1 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 4/5 | 2 | 041 | C_HQRSSYPYTF | 2 |

| 13 | 13 | po | ~ 1 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 082 | C_QQRSSYPPMYTF | 2 |

| 14 | 12 | n.d. | < 0.01 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 12/13 | 1 | 172 | C_QHHYGTPYTF | 2 |

| 15 | 9 | n.d. | ~ 0.1 | 2 | 1 | 159 | C_AIYYYGKDYFDY | FL16.1 | 2 | 23 | 1 | 179 | C_QNGHSFPYTF | 2 |

| 16 | 1 | n.d. | ~ 0.1 | 3 | 1 | 138 | C_ERLRNWYFDV | SP2.3,4,6 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 192 | C_HQYLSSFTF | 4 |

| 17 | 9 | mo | ~ 0.1 | 3 | 1 | 120 | C_ARAGAYYRSWFAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 129 | C_QQGQSYPFTF | 4 |

| 18 | 2 | po | ~ 1 | 5 | 1 | 192 | C_ARHNYGSSYYAMDY | FL16.1 | 4 | 12/13 | 1 | 172 | C_QHHYGTPRTF | 1 |

| 19 | 9 | po | n.d. | 5 | 1 | 176 | C_ASLYDGYY | SP2.9 | 2 | 4/5 | 1 | 154 | C_HQYHRSPPTF | 2 |

| 20 | 6 | po | ~ 0.3 | 5 | 1 | 176 | C_ARGAGGYYAMDY | n.f. | 4 | 12/13 | 1 | 172 | C_QHYGTPWTF | 1 |

| 21 | 12 | po | n.d. | 5 | 1 | 165 | C_ARELFFAY | n.f. | 3 | 1 | 1 | 122 | C_SQSTHVPYTF | 2 |

| 22 | 11 | mo | ~ 1 | 5 | 1 | 160 | C_ARPHEG | n.f. | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 050 | C_QQWSSNPYTF | 2 |

| 23 | 11 | po | ~ 1 | 5 | 1 | 139 | C_ASQTGTLYAMDY | Q52 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 154 | C_HQYHRSPPTF | 1 |

| 24 | 3 | n.d. | n.d | 5 | 1 | 139 | not complete | 1 | 1 | 115 | C_FQGSHVPLTF | 5 | ||

| 25 | 5 | n.d. | n.d. | 5 | 1 | 135 | C_ARHYYGSSWFAY | FL16.1 | 3 | 19/28 | 1 | 201 | C_QQYNSYTF | 4 |

| 26 | 9 | n.d. | ~ 1 | 5 | 1 | 131 | C_ARHRGLRRPFDY | SP2.2 | 2 | 12/13 | 1 | 170 | C_QHFWGTPPTF | 1 |

| 27 | 9 | po | ~ 0.1 | 7 | 1 | 158 | C_ARDKASSYSFRYYAMDY | SP2.6,7 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 192 | C_HQYLSRTF | 1 |

| 28 | 6 | po | ~ 0.1 | 9 | 1 | 156 | C_ARNSVRAMDY | SP2.5,7,8 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 163 | C_QQWSGYPFTF | 4 |

| 29 | 10 | po | ~ 0.07 | 5 | 1 | 160 | C_ARPHVG | Q52 | 3 | n.d. | ||||

| 30 | 13 | po | n.d. | 5 | 1 | 139 | C_AREIYYGSSYHWYFDV | FL16.1 | 1 | n.d. | ||||

| 31 | 2 | po | n.d. | n.d. | 4/5 | 2 | 166 | C_QQFTSSPSTF | 2 | |||||

| 32 | 7 | po | n.d. | n.d. | 19/28 | 1 | 201 | C_QQYNYPYTF | 2 | |||||

Legend

The annotation of antibodies indicates their generation from non-immunized mice and is followed by a sequential number (GenBank accession no. HQ446528-57 and HQ446558-87).

Fusions from which antibodies were obtained are indicated by numbers.

Cross-reactivity of antibodies was tested with varies autologous antigens (see text and Supporting Information Table I) and is indicated: po – poly-, mo – mono-, bi – bispecific.

The relative affinities were measured in a hapten inhibition test in comparison to IdOx1 IgM anti-phOx antibody H11.5 (μ,κ). Equal and enhanced affinities are indicated in bold.

Indicates the VH or VL gene family.

In the integrative database VBASE2, the genes are classified: for class 1 genes there is genomic and rearranged evidence, for class 2 genes only genomic evidence and for class 3 genes only rearranged evidence.

VH and VL genes numbers according to the integrative database VBASE2.

The amino acid sequences of the third hypervariable regions of the heavy and light chains are given in the one-letter code. Amino acids in bold and underlined are derived from D gene-segments while those in italics are generated by N region insertions and P nucleotides.

The VH gene shows several deviations from the indicated VH1 family Class 2 reference gene. Since the entire VH1 locus is not known and the corresponding VL gene is in germline configuration, we assume that this antibody nevertheless has to be regarded as a natural antibody.

n.d. – not determined; n.f. – not found

It is a common view that nAbs bind with low affinity to their respective Ag. Thus we compared the relative affinities of the anti-phOx nAb with that of the primary TD Ag-induced IdOx1 mAb H11.5 (μ,κ) (Table 1). As expected, most natural anti-phOx showed much lower affinities. However, eight nAbs displayed an affinity comparable to mAb H11.5, and nat11 actually exhibited a 14-times higher affinity. The nat11 nAb was encoded by VHOx1 (VH171 in the integrative database VBASE2), but it used Vκ115 and it did not contain the Ox1-typical DRG amino acid sequence in CDR3-H3. Moreover, nat11 did not react with our IdOx1-specific mAb [15]. These results demonstrated that, contrary to the common view, the natural BALB/c anti-phOx repertoire does contain a number of Ab of equal or even higher affinity than the classic clonotype Ox1, which exhibits the highest affinity in the primary TD antigen-induced anti-phOx response [3]. This is reminiscent of the observation that the affinity of human nAbs can be similar to tetanus vaccine-induced immune antibodies [14].

We obtained complete VH/VL sequences from 28 nAbs. We also obtained either a VH or a VL sequence from two additional nAbs (Table 1). Together, these Ab were encoded by 21 VH and 20 VL genes, and every VH/VL combination proved unique (Table 1). Five of the 28 nAb used the VHOx1 gene VH171. None used the VκOx1 gene Vκ072. Hence, since the Ox1 clonotype was not found among anti-phOx nAbs, it would appear that this clone contributes minimally, if at all, to the anti-phOx nAb repertoire. This would support the view that Ox1 Ab VH171-Vκ072 clones are more likely to be drawn from the conventional B2 B cell subset, as previously suggested in the case of influenza virus [16].

Composition of primary anti-phOx antibodies induced by the TI-2 antigen phOx-Ficoll

Immunization with TD and TI Ag typically leads to an early appearance of activated proliferating B cells within the PALS [17], and both responses are presumed to derive from the same shared B2 repertoire [18]. Because of these similarities and the observation that T cells can have a regulatory influence on TI-2 responses [4], we analyzed the clonal repertoire of 19 TI-2-induced mAb to see if the IdOx1 is as dominant as in the TD response, or whether the TI repertoire is similarly heterogeneous as the NP-specific repertoire in C57BL/6 mice [19]. Our TI-2-induced anti-phOx mAb were encoded by 13 VH and 10 VL genes (Table 2). This level of heterogeneity was similar to that observed in the NP-Ficoll response [19]. Compared with IdOx1 Ab, 12 (63%) of the 19 non-IdOx1 mAb exhibited an equal affinity to phOx. Two additional mAb actually exhibited an enhanced affinity for the antigen. In contrast to the anti-phOx nAb, eight (42%) of the 19 TI-induced anti-phOx mAb were encoded by Vκ072. Of these, only two (11%) were of the IdOx1, both with a VH171-encoded heavy chain and a DRG amino acid sequence in CDR-H3. And, a large proportion of these TI-2 anti-phOx IgM exhibited similar or even higher affinities than IdOx1 IgM H11.5. Hence, the TI-2 antigen phOx-Ficoll can activate IdOx1 B cells, but this anti-phOx response is just as heterogeneous as anti-phOx nAb, with IdOx1 Ab representing a minor subset of the TI-2 response (Table 2).

Table 2.

VH/VL gene combinations of primary IgM anti-phOx antibodies induced by immunization with the thymus-independent type 2 antigen phOx-Ficoll

| mAb TI7a |

rel. Aff.b |

VH chain genes | VL chain genes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Famc | Classd | IGHVe | CDR3-H3f | D | J | Famc | Classd | IGKVe | CDR-L3f | J | ||

| 01 | ~ 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 643 | C_ARDYGTY | n.f. | 2 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 02 | ~ 1 | 1 | 1 | 585 | C_ASYYGHY | n.f. | 2 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPPFTF | 5 |

| 03 | ~ 0.1 | 1 | 2 | 547 | C_ASWLLRKGYFDY | SP2.9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 115 | C_FQGSHVPRTF | 1 |

| 04 | ~ 1 | 1 | 1 | 532 | C_AKGVGDY | SP2.6inv | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 050 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 05 | ~ 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 532 | C_ARSRGDY | n.f. | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 06 | ~ 1 | 1 | 3 | 396 | C_ARDYGDY | n.f. | 2 | 2 | 1 | 099 | C_VQGTHFPLTF | 5 |

| 07 | ~ 1 | 2 | 1 | 183 | C_ARNSGDY | ST4 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 08 | ~ 1 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDHGAY | SP2.2,9inv | 3 | 9A | 1 | 108 | C_LQYASYPPTF | 5 |

| 09g | ~ 1 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGLD | ST4 | 2 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 10 | ~ 1 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 11 | ~ 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDGGAY | SP2.9 | 3 | 21 | 1 | 210 | C_QQSKEVPYTF | 2 |

| 12 | ~ 8 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDWADY | Q52 | 3 | 9a | 1 | 112 | C_LQYASSPPTF | 1 |

| 13 | ~ 1 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDYYGSSYETY | FL16.1 | 3 | 9b | 1 | 106 | C_LQHGESPFTF | 4 |

| 14 | ~ 0.5 | 3 | 1 | 120 | C_ARGSHYYGYDY | FL16.2 | 2 | 23 | 1 | 173 | C_QQSNSWPLTF | 5 |

| 15 | ~ 0.5 | 5 | 1 | 181 | C_ARVGRLLRYAMDY | FL16.1,2 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 16 | ~ 0,5 | 5 | 1 | 163 | C_ARYDYYAMDY | SP2.11 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 122 | C_SQSTHVPLTF | 5 |

| 17 | ~ 3 | 5 | 1 | 139 | C_ARDYRYDDPFAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 18 | ~ 0.5 | 7 | 1 | 158 | C_ARGDYYGSWFAY | FL16.2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 115 | C_FQGSHVPYTF | 2 |

| 19 | ~ 1 | 2 | 1 | 137 | C_VRLRGFAY | SP2.11 | 3 | not determined | ||||

Legend

The annotation of antibodies indicates their generation after TI-2 immunization and fusion on day 7 followed by a sequential number (GenBank accession no. HQ446588-606 and HQ446607-624).

The relative affinities were measured in a hapten inhibition test in comparison to IdOx1 IgM anti-phOx antibody H11.5. Equal and enhanced affinities are indicated in bold.

Indicates the VH or VL gene family.

In the integrative database VBASE2, the genes are classified: for class 1 genes there is genomic and rearranged evidence, for class 2 genes only genomic evidence and for class 3 genes only rearranged evidence.

VH and VL genes numbers according to the integrative database VBASE2.

The amino acid sequences of the third hypervariable regions of the heavy and light chains are given in the one-letter code. Amino acids in bold and underlined are derived from D gene-segments while those in italics are generated by N region insertions and P nucleotides.

The IdOx1 gene combination VH171/Vκ072 is on gray background.

Since direct TI-2-mediated activation of B cells with resulting proliferation and Ab secretion critically depends on clustering of membrane-bound BCR by the multivalent ligand [20], the avidity of this interaction is presumably an important factor for clonal selection in this response. Since it has been shown that memory cells, induced with the TD form of the TI-2 antigen dextran, can be activated with plain dextran [18] we induced high-affinity phOx-specific memory cells by tertiary immunization with phOx-coupled chicken serum albumin (CSA) and eight weeks later re-stimulated the mice with phOx-Ficoll. Hybridoma anti-phOx mAb were analyzed to see if they resembled either those from TD-induced memory cells or those from the TI-2 response. In contrast to the primary TI-2 response, no IgM but 16 mAb of the IgG class were obtained. These IgG mAb exhibited a greatly restricted repertoire of VH and VL genes (Table 3). Eight (50%) of the 16 mAb used VH171 and eleven (69%) of the mAb were encoded by Vκ072. However, only five (31%) of the 16 mAb used the canonical IdOx1 VH171/Vκ072 gene combination. The eleven Vκ072-derived VL domains all included either the H33N (2 mAb) or H33Q (9 mAb) classic early affinity-enhancing mutations; and all of them also showed the Y35F mutation (Supporting Information Fig. 1). Among the VH domains, five of the eight VH171-using mAb exhibited the well-known mutations S31T (3 mAb) or S31N (2 mAb) [3]. Hence, all these TI-2 re-stimulated IgG anti-phOx mAb exhibited well-known characteristics of TD memory Ab, as reported earlier [3]. This applied also to the appearance of gene combinations of one highly mutated variable gene with the other in either germline or near germline configuration as previously observed in anti-phOx memory responses [3]. We have argued that such gene combinations might be generated by receptor revision [21]. These results suggest that, in the presence of high affinity TD-induced IgG memory cells, a TI-2 immunization appears to stimulate these cells with seemingly no concomitant activation of naïve TI-2-inducible B cells.

Table 3.

VH/VL gene combinations of IgG-anti-phOx antibodies after tertiary TD and a following primary TI immunization

| mAb 3D1Ia |

Isotype | VH chain genes | VL chain genes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Famb | Classc | IGHVd | CDR-H3e | D | J | Famb | Classc | IGKVd | CDR-L3e | J | ||

| 01 | γ1,κ | 2 | 1 | 183 | C_ARDGGDY | SP2.9 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSDPLTF | 5 |

| 02 | γ1, κ | 2 | 1 | 183 | C_ARDGGDY | SP2.9 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 03 | γ1,κ | 2 | 1 | 175 | C_ARDWGDY | Q52 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNSPLTF | 5 |

| 04 | γ1,κ | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDGGDY | SP2.9 | 2 | 12/13 | 1 | 174 | C_QHFWSPPWTF | 1 |

| 05 | γ2b,κ | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGDY | SP2.11 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 110 | C_LQVTHVPWTF | 1 |

| 06f | γ1,κ | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDGGDY | SP2.9 | 2 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_HQWSGHPPITF | 4 |

| 07 | γ1,κ | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDGGDY | SP2.9 | 2 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSGHPPITF | 4 |

| 08 | γ1,κ | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDGGDY | SP2.9 | 2 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSGSPPITF | 4 |

| 09 | γ2b,κ | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGDY | SP2.11 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWTSNPLTF | 5 |

| 10 | γ1,κ | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDGGDY | SP2.9 | 2 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSGHPPITF | 4 |

| 11 | γ1,κ | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ATYDGFAY | SP2.9 | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 050 | C_QQWISNPPMLTF | 5 |

| 12 | γ1,κ | 5 | 1 | 139 | C_ARDGGDY | FL16.1 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 13 | γ1,κ | 5 | 1 | 139 | C_ARDGGDY | FL16.1 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 14 | γ1,κ | 5 | 1 | 139 | C_ARDGGDY | FL16.1 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 15 | γ1,κ | 6 | 1 | 114 | C_ISVSPWFVY | SP2.11inv | 3 | 9A | 1 | 108 | C_LQYASYPFTF | 4 |

| 16 | γ1,κ | 2 | 1 | 186 | C_ARDWGDY | Q52 | 4 | not determined | ||||

Legend

The annotation of antibodies indicates their generation after 3 TD and a final TI-2 immunization, fusion 3 days later plus a sequential number (GenBank accession no. HQ446694-446709 and HQ446710-446724).

Indicates the VH or VL gene family.

In the integrative database VBASE2, the genes are classified: for class 1 genes there is genomic and rearranged evidence, for class 2 genes only genomic evidence and for class 3 genes only rearranged evidence.

VH and VL genes numbers according to the integrative database VBASE2.

The amino acid sequences of the third hypervariable regions of the heavy and light chains are given in the one-letter code. Amino acids in bold and underlined are derived from D gene-segments while those in italics are generated by N region insertions and P nucleotides.

The IdOx1 gene combination VH171/Vκ072 is on gray background.

Dichotomy of primary TD antigen-induced IgM and IgG anti-phOx antibodies

To compare these results with the primary TD response, in a first fusion we isolated only primary IgM anti-phOx mAb after immunization with phOx-CSA (Table 4). To our surprise, this early primary TD-induced IgM repertoire turned out to be just as heterogeneous as that of the TI-2 response (Table 2). Together with 12 mAb of a second fusion, 17 different VH and 12 different VL genes contributed to this IgM response, a heterogeneity which is comparable to that of the TI-2 response (Table 2). A small percentage of these mAb used the VH171 gene and was of the Ox1 clonotype. Importantly, a quarter of these 32 primary non-IdOx1 IgM exhibited an identical, and two (6%) even higher, affinities for phOx than the IdOx1 mAb H11.5. Conversely, VH171 usage as well as expression of the IdOx1 gene combination increased among IgG mAb which also exhibited a genetic restriction with only 4 VH and 4 VL coding genes (Table 5).

Table 4.

VH/VL gene combinations of early day 7 primary TD-induced IgM anti-phOx antibodies

| mAb TD7a |

Fub | rel. Aff |

VH chain genes | VL chain genes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Famc | Classd | IGHVe | CDR-H3f | D | J | Famc | Classd | IGKVe | CDR-L3f | J | |||

| 01 | 1 | ~ 1 | 1 | 1 | 702 | C_TRLDAFAY | Q52 | 3 | 9A | 1 | 108 | C_LQYASYPPTF | 1 |

| 02 | 1 | ~ 1 | 1 | 1 | 668 | C_ARDGGDY | SP2.9 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 050 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 03 | 2 | ~ 0.2 | 1 | 2 | 627 | C_VRYYFDY | n.f. | 2 | 9B | 2 | 121 | C_LQYDEFPYTF | 2 |

| 04 | 1 | < 0.05 | 1 | 1 | 532 | C_TNLRLQAY | FL16.2 | 3 | 9A | 1 | 108 | C_LQYASYPPTF | 1 |

| 05 | 1 | ~ 1 | 1 | 1 | 532 | C_ANLRLQAY | FL16.2 | 3 | 9A | 1 | 108 | C_LQYASYPPTF | 1 |

| 06 | 1 | ~ 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 532 | C_AKRRGDY | SP2.3,4,6 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 07 | 1 | n.d. | 1 | 3 | 398 | C_AGKYGGAY | SP2.3,4 | 3 | 19/28 | 1 | 203 | C_QQYSSYPYTF | 2 |

| 08 | 1 | ~ 0.05 | 1 | 3 | 398 | C_AGKYGGAY | SP2.2,3 | 3 | 19/28 | 1 | 203 | C_QQYSSYPYTF | 2 |

| 09 | 2 | ~ 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 364 | C_ARSYDGYWRFDY | SP2.9 | 2 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPPTF | 5 |

| 10 | 1 | ~ 0.2 | 1 | 3 | 286 | C_ARWGYGNAY | ST4 | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 078 | C_QQYSGYPLTF | 1 |

| 11 | 2 | ~ 8 | 1 | 2 | 034 | C_ARPDGNYVAWFAY | SP2.8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 115 | C_FQGSHVPYTF | 2 |

| 12 | 1 | ~ 0.05 | 1 | 3 | 023 | C_AYYYGAY | FL16.1 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 129 | C_QQGQSYPLTF | 5 |

| 13 | 2 | ~ 9.0 | 2 | 1 | 190 | C_AGGRSFAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 23 | 1 | 168 | C_QQSNSWPTLTF | 5 |

| 14 | 2 | ~ 0.1 | 2 | 1 | 190 | C_AGGRSFAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 139 | C_QQYSKLPYTF | 2 |

| 15g | 2 | ~ 1 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 16 | 1 | ~ 0.05 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGAYh | ST4 | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 17 | 1 | ~ 1 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 18 | 1 | n.d. | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGAY | ST4inv | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 19 | 2 | ~ 1 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGDY | SP2.11 | 2 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPP | n.d. |

| 20 | 2 | ~ 0.2 | 3 | 1 | 128 | C_ARATARAVAWFAY | ST4 | 3 | 9B | 1 | 121 | C_LQYDEFPYTF | 2 |

| 21 | 2 | ~ 0.3 | 5 | 1 | 181 | C_ARVGGRGHYFDY | SP2.11 | 2 | 23 | 1 | 168 | C_QQSNSWPRTF | 1 |

| 22 | 1 | ~ 0.2 | 5 | 1 | 163 | C_ARNYLYAMDY | SP2.2–2.7 | 4 | 23 | 1 | 173 | C_QQSNSWPYTF | 2 |

| 23 | 1 | ~ 0.3 | 7 | 1 | 158 | C_ARGILGGWFAY | Q52 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 097 | C_WQGTHFYTF | 2 |

| 24 | 1 | ~ 1 | 7 | 1 | 158 | C_ARGYDYGAWFAY | SP2.2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 115 | C_FQGSHVPYTF | 2 |

| 25 | ? | n.d. | 1 | 1 | 532 | C_ARSDYYGYDEGAWFAY | SP2.3,4,6 | 3 | n.d. | ||||

| 26 | 2 | n.d. | 2 | 1 | 137 | C_VRVAYYGSSW | FL16.1 | 1 | n.d. | ||||

| 27 | 2 | ~ 0.2 | 6 | 1 | 114 | C_TRPNWDSPWFAY | Q52 | 3 | n.d. | ||||

| 28 | 1 | n.d. | n.d. | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 | |||||

| 29 | 1 | n.d. | n.d. | 1 | 1 | 115 | C_FQGSHVPRTF | 1 | |||||

| 30 | 1 | ~ 1 | n.d. | 9A | 1 | 108 | C_LQYASYPPTF | 1 | |||||

| 31 | 1 | < 0.05 | n.d. | 9B | 1 | 121 | C_LQYDEFPYTF | 2 | |||||

| 32 | 1 | ~ 0.5 | n.d. | 9A | 1 | 108 | C_LQYASYPPTF | 1 | |||||

Legend

The annotation of antibodies indicates their generation after primary TD immunization and fusion on day 7 followed by a sequential number (GenBank accession no. HQ446625-446651 and HQ446659-446687).

The antibodies are derived from 2 fusions. Since fusion 1 was only screened for IgM-anti-phOx antibodies there are no IgG antibodies.

Indicates the VH or VL gene family.

In the integrative database VBASE2, the genes are classified: for class 1 genes there is genomic and rearranged evidence, for class 2 genes only genomic evidence and for class 3 genes only rearranged evidence.

VH and VL genes numbers according to the integrative database VBASE2.

The amino acid sequences of the third hypervariable regions of the heavy and light chains are given in the one-letter code. Amino acids in bold and underlined are derived from D gene-segments while those in italics are generated by N region insertions and/or P nucleotides.

The IdOx1 gene combination VH171/Vκ072 is on gray background.

This antibody showed mutations in VH: 1 in CDR2 and 1 in FR3.

n.d. not determined

Table 5.

VH/VL gene combinations of primary TD-induced day 7 IgG anti-phOx antibodies

| mAb TD7a |

Fub | VH chain genes | VL chain genes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Famc | Classd | IGHVe | CDR-H3f | D | J | Famc | Classd | IGKVe | CDR-L3f | J | ||

| 33 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 201 | C_AKDSGDY | SP2.2 | 4 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSTPLTF | 5 |

| 34 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDGGAY | SP2.9 | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 157 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 35g | 2 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGAY | SP2.11 | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 36 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGDY | ST4inv | 3 | 4/5 | 1 | 072 | C_QQWSSNPLTF | 5 |

| 37 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 437 | C_ARDYYYGSKLLYYFDV | FL16.1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 137 | C_QQGNTLPPTF | 1 |

| 38 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 114 | C_TRPNWDSPWFAY | Q52 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 115 | C_FQGSHVPRTF | 1 |

| 39 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 171 | C_ARDRGDY | ST4inv | 4 | not determined | ||||

Legend

The annotation of antibodies indicates their generation after TD immunization and fusion on day 7 followed by a sequential number (GenBank accession no. HQ446652-446658 and HQ446688-446693).

The antibodies are derived from the second fusion the IgM antibodies of which are depicted in Table 4.

Indicates the VH or VL gene family or subgroup, respectively.

In the integrative database VBASE2, the genes are classified: for class 1 genes there is genomic and rearranged evidence, for class 2 genes only genomic evidence and for class 3 genes only rearranged evidence.

VH and VL genes numbers according to the integrative database VBASE2.

The amino acid sequences of the third hypervariable regions of the heavy and light chains are given in the one-letter code. Amino acids in bold and underlined are derived from D gene-segments while those in italics are generated by N region insertions and P nucleotides.

The IdOx1 gene combination VH171/Vκ072 is on gray background.

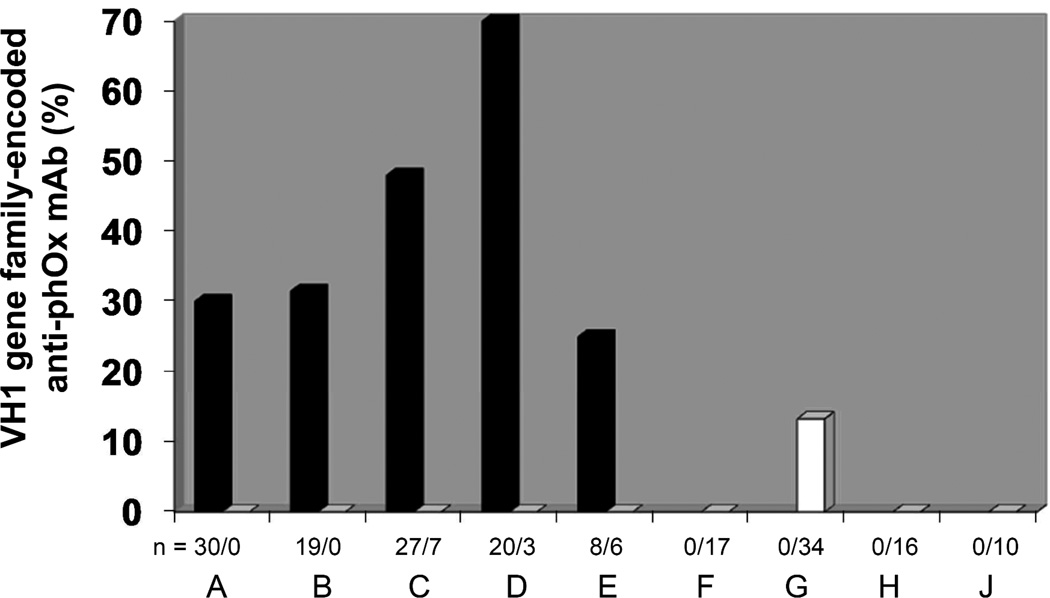

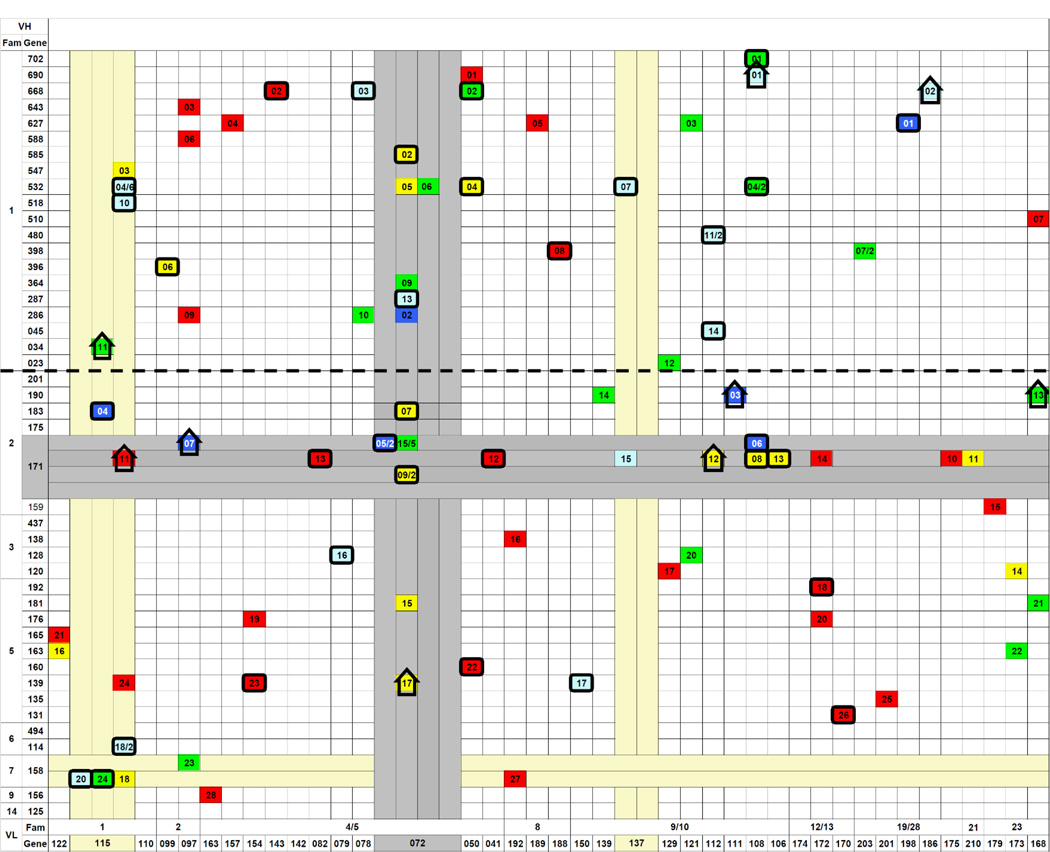

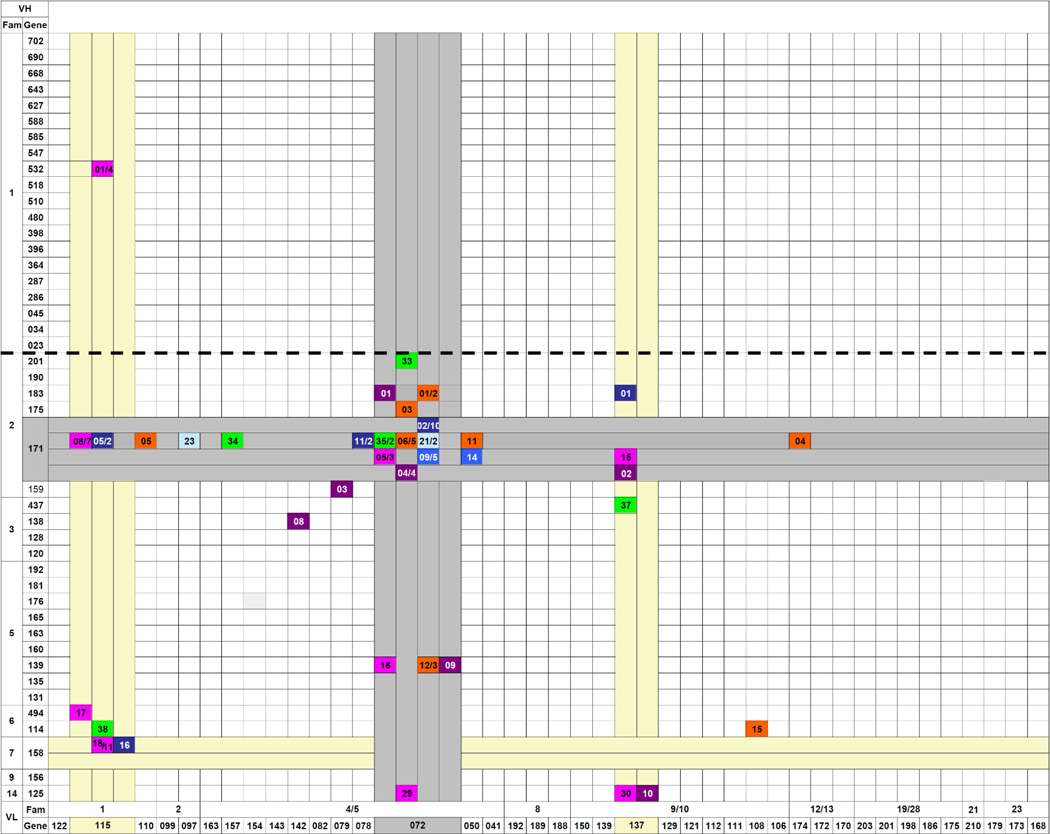

The VH/VL combinations of all these mAb and, for completion of the anti-phOx repertoires of both Ig classes, VH/VL combinations of anti-phOx mAb from a previous investigation [21] are depicted in Tables 6 and 7. The previously reported IgM and IgG mAb include those generated after (a) TI-2 pre-immunization with phOx-Ficoll and TD immunization 1 month later and fusion on day 7 (1°TI>1mo>1°TD day 7), (b) TI-2 pre-immunization and TD immunization 3 months later and fusion day 7 (1°TI>3mo>1°TD day 7), (c) TI-2 pre-immunization, TD immunization 3 months later and fusion on day 14 (1°TI>3mo>1°TD day 14), and (d) TI-2 pre-immunization, TD primary immunization after 3 months followed by a secondary TD immunization 8 weeks later and fusion on day 3 (1°TI>3mo>2°TD). In addition, Table 7 contains VH/VL combinations of TD-induced quaternary IgG anti-phOx mAb (4°TD) the genetic make-up of which is shown in Supporting Information Fig. 2 and Supporting Information Table 2. Importantly and irrespective of the immunization scheme, IgM antibodies of both the natural and the TI-2- and TD-induced repertoires proved to be highly diverse (41 VH; 37 Vκ), including non-IdOx1 with equal or even higher affinities than IdOx1 mAb (Table 6). In contrast, IgG mAb use a restricted repertoire (14 VH; 12 Vκ) encoded largely by either the IdOx1 genes VH171 or Vκ072 or a combination of these genes and a limited number of other gene sets (Table 7). Intriguingly, a large proportion of IgM is encoded by genes of the VH1 family, whereas usage of VH1 gene family members among primary as well as memory IgG was only found in one particular fusion after a 1°TI>3m>2°TD challenge regimen. Thus B cells using VH1 family-encoded IgM appeared to rarely produce class switched anti-phOx IgG (Fig. 1).

Table 6.

Gene usage of IgM antibodies in anti-2-phenyl-oxazolone immune responses of BALB/c mice

|

Legend

Each filled cell symbolizes an IgM anti-phOx Ab with a particular VH/VL combination. The numbers indicate a particular Ab within a group of Ab the generation of which is described below. Numbers after a slash indicate how many Ab of a particular gene combination were found. Cells of non-IdOx1 Ab exhibiting identical or similar affinities as IdOx1 Ab are marked with bold rectangles. Non-IdOx1 exhibiting higher affinities than IdOx1 Ab are marked with a bold upright arrow. The bold dashed line highlights the border between VH1 and VH2 family-encoded genes.

- natural IgM obtained from non-immunized mice.

- natural IgM obtained from non-immunized mice.

- primary IgM day 7 Ab induced with phOx-Ficoll (TI-2 antigen)

- primary IgM day 7 Ab induced with phOx-Ficoll (TI-2 antigen)

- primary day 7 TD-(phOx-CSA)-induced Ab

- primary day 7 TD-(phOx-CSA)-induced Ab

- Ab obtained after initial TI-2 immunization and a primary TD immunization 1 month later and fusion on day 7

- Ab obtained after initial TI-2 immunization and a primary TD immunization 1 month later and fusion on day 7

- Ab were obtained after an initial TI-2 immunization and a primary TD immunization 3 months later and fusion on day 7

- Ab were obtained after an initial TI-2 immunization and a primary TD immunization 3 months later and fusion on day 7

Table 7.

Gene usage of IgG antibodies in anti-2-phenyl-oxazolone immune responses of BALB/c mice

|

Legend

Each cell marked with a colored ellipse symbolizes an IgG anti-phOx Ab with a particular VH/VL combination. The numbers indicate a particular Ab within a group of Ab the generation of which is described below. Numbers after a slash indicate how many Ab of a particular gene combination were found. The bold dashed line highlights the border between VH1 and VH2 family-encoded genes.

- primary day 7 TD-(phOx-CSA)-induced Ab

- primary day 7 TD-(phOx-CSA)-induced Ab

- Ab obtained after initial TI-2 immunization and a primary TD immunization 1 month later and fusion on day 7

- Ab obtained after initial TI-2 immunization and a primary TD immunization 1 month later and fusion on day 7

- Ab were obtained after an initial TI-2 immunization and a primary TD immunization 3 months later and fusion on day 7

- Ab were obtained after an initial TI-2 immunization and a primary TD immunization 3 months later and fusion on day 7

- initial TI-2 immunization, 3 months pause, followed by a primary TD immunization and fusion on day 14

- initial TI-2 immunization, 3 months pause, followed by a primary TD immunization and fusion on day 14

- initial TI-2 immunization, 3 months pause, primary TD followed by a secondary TD immunization 8 weeks later and fusion on day 3

- initial TI-2 immunization, 3 months pause, primary TD followed by a secondary TD immunization 8 weeks later and fusion on day 3

- tertiary TD-immunized mice received a final immunization with TI-2 antigen (phOx-Ficoll) 8 weeks after the last TD immunization, fusion on day 3

- tertiary TD-immunized mice received a final immunization with TI-2 antigen (phOx-Ficoll) 8 weeks after the last TD immunization, fusion on day 3

- mice received a quaternary TD immunization and spleen cells were fused 3 days after the last immunization

- mice received a quaternary TD immunization and spleen cells were fused 3 days after the last immunization

Figure 1. Percentages of VH1 gene family-encoded IgM and IgG anti-phOx antibodies.

The following groups of mAb were analyzed: (A) natural IgM obtained from non-immunized mice; (B) primary IgM (on day 7) after induction with phOx-Ficoll (TI-2 antigen); (C) primary TD-(phOx-CSA)-induced mAb obtained on day 7 after induction; (D) mAb obtained after initial TI-2 immunization, followed by a primary TD immunization 1 month later and fusion thereafter on day 7; (E) mAb were obtained after an initial TI-2 immunization, followed by a primary TD immunization 3 months later and fusion thereafter on day 7; (F) IgG mAb obtained after initial TI-2 immunization, followed by a 3 month pause, followed by a primary TD immunization and fusion thereafter on day 14; (G) IgG mAb obtained after initial TI-2 immunization, followed by a primary TD immunization after a 3 month pause, followed by a further secondary TD immunization 8 weeks later and fusion thereafter on day 3; (H) IgG mAb obtained after tertiary TD-immunized mice received a final immunization with TI-2 antigen (phOx-Ficoll) 8 weeks after the last TD immunization, fusion thereafter on day 3; (J) IgG mAb obtained after mice received a quaternary TD immunization and spleen cells were fused 3 days after the last immunization. Black bars show values for IgM mAbs, white bars show values for IgG. n indicates the numbers of IgM/IgG mAb, respectively. For further information see legend to Fig. 2.

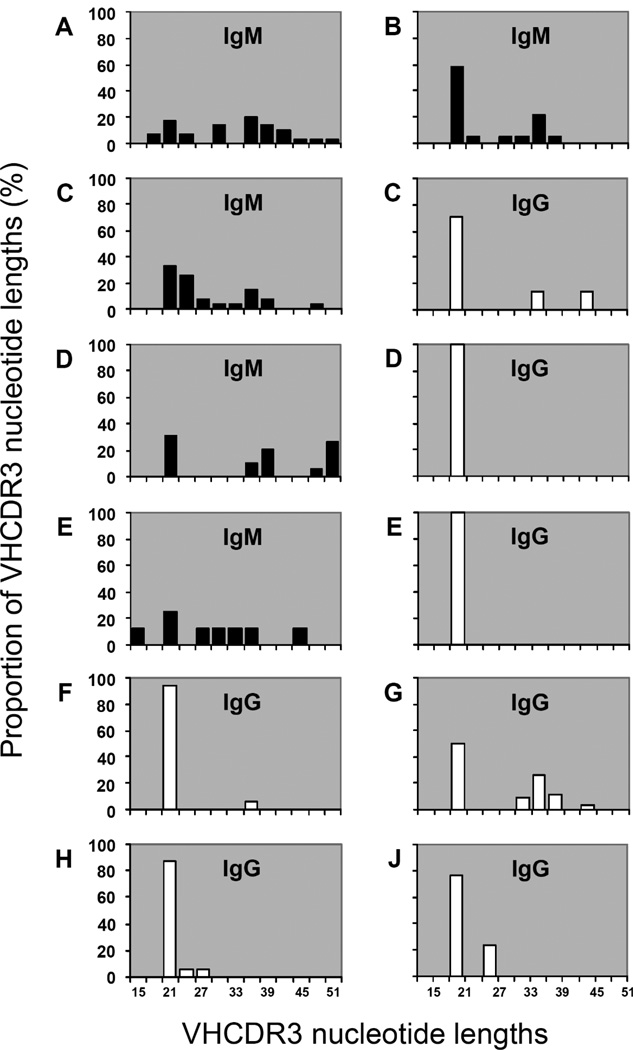

Shortening and unification of CDR3-H3 lengths during class switch recombination

In mice [22] and humans [23, 24] it has been observed that Ab containing somatic mutations in VH and VL or memory Ab exhibit shorter CDR-H3 intervals than Ab in germline configuration. This poses the question as to when these Ab with truncated CDR-H3 are selected during the sequential steps of immune maturation. We compared the CDR-H3 lengths of all anti-phOx mAb (Tables 6 and 7, Fig. 2) and found that the CDR-H3 lengths of natural as well as TI-2- and TD-induced IgM are rather heterogeneous, ranging from 15 to 51 nucleotides. In contrast, the CDR-H3 lengths of all the IgG populations, which ranged from primary to quaternary responses, are much more homogeneous and show a dominant short length of 21 nucleotides throughout. The only exception was seen among secondary Ab, half of which showed CDR-H3 lengths of 33–45 nucleotides. However, this appears to be a transient phenomenon, and these Ab appear to be counter selected since they are not retrieved in tertiary and quaternary responses (Fig. 2H and J). Thus, the composition of the CDR-H3 loop appears to influence the selection, survival or proliferation of the anti-phOx B cells that underwent CSR.

Figure 2. Distribution of CDR-H3 nucleotide lengths among anti-phOx antibodies.

CDR-H3 nucleotide numbers of anti-phOx mAb contained in Tab. 6 were counted and assorted according to their length. IgM and IgG mAb are indicated by black and white bars, respectively. The following groups of mAb were analyzed: (A) natural IgM obtained from non-immunized mice (n = 30, 14 spleens); (B) primary IgM obtained 7 days after induction with the TI-2 antigen phOx-Ficoll (n = 19, 3 spleens); (C) primary IgM (n = 27, left) and IgG (n = 7, right) obtained 7 days after induction with TD antigen phOx-CSA (2 spleens); (D) IgM (n = 20, left) and IgG (n = 3, right) were obtained after initial TI-2 immunization and a primary TD immunization 1 month later and fusion thereafter on day 7 (1 spleen); (E) IgM (n = 8, left) and IgG (n = 6, right) were obtained after an initial TI-2 immunization and a primary TD immunization 3 months later and fusion thereafter on day 7 (1 spleen); (F) IgG (n = 17, 1 spleen) were produced after initial TI-2 immunization, followed by a 3 month pause, followed by a primary TD immunization and fusion thereafter on day 14; (G) IgG (n= 34, 1 spleen) were obtained after initial TI-2 immunization, followed by a primary TD immunization after a 3 month pause, followed by a further secondary TD immunization 8 weeks later and fusion thereafter on day 3; (H) IgG (n = 16, 3 spleens) were obtained after tertiary TD-immunized mice received a final immunization with TI-2 Ag phOx-Ficoll 8 weeks after the last TD immunization, fusion thereafter on day 3; (J) IgG (n = 10, 3 spleens) were obtained after mice received a quaternary TD immunization and spleen cells were fused 3 days after the last immunization.

All VH region amino acid sequences of antibodies depicted in Table 6 and 7 were analyzed with the RANKPEP program [25] (available under http://imed.med.ucm.es/Tools/rankpep.html.) for the prediction of peptides which can be bound by I-Ad and I-Ed MHC-II molecules of the BALB/c strain. Strikingly, a large proportion of these antibodies contained especially CDR-H3-related, MHC-II-presentable peptides (data not shown). However, because of the likely involvement of different idiotypically related T cells, it met our expectation that particular related sequences could not be deduced.

Discussion

These data shed new light on the relationship between activated B cells of the primary and memory responses and the role of VH family and CDR-H3 in influencing CSR. Ab from the early phases of the primary immune response are encoded by germline VH and VL genes and their generally low affinity is improved through somatic hypermutation [26, 27]. In transgenic mouse models, even very low affinity clones can be activated during TI-2 and TD immune responses, but competition for Ag favors high affinity clones during the earliest phases of the response [28, 29]. Since the heterogeneity of the early primary Ab repertoire is reduced in the course of the response, it is the common perception that affinity-driven competition is the mechanism that assures that only B-cell clones expressing high affinity BCR will survive, undergo CSR and enter the memory cell pool [30, 31]. However, our finding that a large fraction of non-IdOx1 IgM Ab exhibiting identical or even higher affinities than IdOx1 Ab (Table 6) are not found in the pool of IgG-secreting hybridomas (Table 7) argues against the view that affinity is the only factor in determining which B cells that respond to initial immunization will successfully transition to long-lived IgG producing memory B cells. If high affinity played the assumed role, then we would have expected that some non-Ox1 clones would have become prevailing contributors to the IgG anti-phOx repertoire, at least in some mice. Since this, however, was not the case, factors other than affinity must be playing a role in determining which B cells preferentially undergo IgM>IgG class switch recombination, or which B cells survive and prosper after CSR.

One possibility might still be that the CSR-related differences of anti-phOx Ab repertoires reflect the activation of different B cell subpopulations, namely nAb-producing B1 cells or B2 cells with the subpopulations of follicular (FO) and marginal zone (MZ) B cells. Thus, are there indications that one of these subpopulations is preferentially involved in the differentiation to Ab-secreting plasma cells, class switching and formation of memory cells? 1.) In one experimental system the primary but not the secondary TD response developed from B cell precursors that expressed high levels of heat-stable antigen (HSAhigh) [32], whereas the majority of HSAlow virgin B cells proved responsible for GC formation and generation of memory cells for the secondary response [33]. Moreover, after in vitro stimulation, only the progeny of HSAlow B cells exhibited somatic mutations [34]. 2.) Blocking with mAb of the interaction of co-stimulatory membrane molecules with their respective ligands at the beginning of GC formation reduced the number of GC B cells and impaired GC maturation and affinity-maturation, while levels of low-affinity antibodies remained unaffected [35]. Since memory B cells were also of low affinity and showed reduced rates of somatic mutations, it was concluded that memory B cells are not only generated in the course of the GC route, but also in a GC-independent manner [35]. 3.) While blood-derived antigens quickly activate innate-like splenic MZ B cells to secretion of weakly self-reactive IgM Ab [36] which are responsible for the transport of the antigen in the form of immune-complexes to the follicles, isotype-switched antibodies are supposed to be mainly derived from FO B cells [9]. Hence, it seems possible that early MZ B cell-derived IgM anti-phOx Ab are eliminated before CSR because of a weak auto-reactivity. A somewhat contradictory finding to this view is the observation that MZ B cell-derived antibodies exhibit shorter CDR-H3 [37–39]. However, while the largest difference of CDR-H3 lengths with 8 bp was observed in MZ B cell-derived Ab that lack N region nucleotides [39], the average difference of 1–2 bp seems to be hardly comparable with the CSR-related reduction of CDR-H3 lengths in the present investigation. Moreover, since all of our 29 nAbs contained N nucleotides and only 1 N nucleotide negative mAb was found in each case among 19 phOx-Ficoll-induced primary IgM (TI7-16) and 27 IgM from the primary TD response (TD7-01), it seems rather unlikely that innate-like MZ B cells contributed to an important extent to our IgM anti-phOx repertoire. 4.) In addition, MZ B cells comprise heterogeneous populations which not only participate in the early but also in late antibody formation and generation of memory cells, and MZ and FO B cells exhibited similar VH gene repertoires and somatic mutations [40]. Analogous results were obtained in the murine Ab response of MZ and FO B cells to virus-like particles, except that somatic mutations were reduced in MZ as compared to FO B cells [41]. Nevertheless, a functional physiological difference between MZ and FO B cell repertoires is indicated by the finding that both populations differed in the expression of 181 genes [42]. Hence, a consistent view that could attribute the CSR-related change of the anti-phOx repertoire to a particular B cell subpopulation seems not to be available.

In contrast, the difference in CDR-H3 lengths between mutated and non-mutated Ab found in overall repertoire analyses could be as high as 10 nucleotides [22–24]. This value is better comparable to the respective range of CDR-H3 lengths in the anti-phOx response. However, it still might be possible that the CSR-association of this effect is unique for the anti-phOx response. We therefore re-examined, as another example, the CDR-H3 lengths of hapten NP-reactive IgM and IgG mAb. These mAb have been described in previous publications by Bothwell and co-workers. The IgM mAb (Supporting Information Table 3) are representative of a TI-2 response induced with NP-Ficoll [19]. They use a diverse repertoire of VH genes and D segments and their CDR-H3 amino acid sequences are encoded by 18–42 nucleotides. A comparable set of IgM mAb induced with the TD Ag NP-coupled chicken gamma globulin (NP-CGG) could not be found in the literature. Primary TD-induced IgG [43], however, are encoded by very few VH genes and use the DFL16.1 segment almost exclusively (Supporting Information Table 4). In CDR-H3, a coding length of 33 nucleotides dominated. Shorter sequences could not be found, but longer ones were still observed. However, in immune-maturated secondary TD-induced anti-NP IgG [44] a further restriction of VH gene and D segment usage as well as CDR-H3 lengths was noticed (Supporting Information Table 5). Strikingly, all IgG anti-NP show a common mostly DFL16.1-derived stretch of tyrosine-tyrosine-glycine (YYG) in the middle of CDR-H3. We regard this as an indication that it is the CDR-H3 sequence that is important for the observed clonal restrictions and not the CDR-H3 length as such. These results from the anti-NP response would suggest that the CSR-associated focusing of CDR-H3 lengths is not restricted to the anti-phOx response, and could be a more general phenomenon.

It has been proposed that a T-independent phase generally precedes the cognate MHC-mediated T-B collaboration during TD responses [7]. According to this `two-phase model of B cell activation´, B cells presumably of the extrafollicular foci are initially expanded and activated to early IgM secretion which, after complexation with antigen, assists strong primary and secondary Ab responses via binding to complement receptors CR2/CR1 on B cells. However, neither the two pathways of extrafollicular and GC-mediated generation of Ab-forming plasma cells and memory cells nor the proposal of a T cell-independent step of induction of TD Ag-induced IgM offer an explanation for the difference of IgM and IgG repertoires. Since an affinity-based selection is also not fully consistent with the data, we presume that another mechanism is likely responsible for the restricted IgG repertoire.

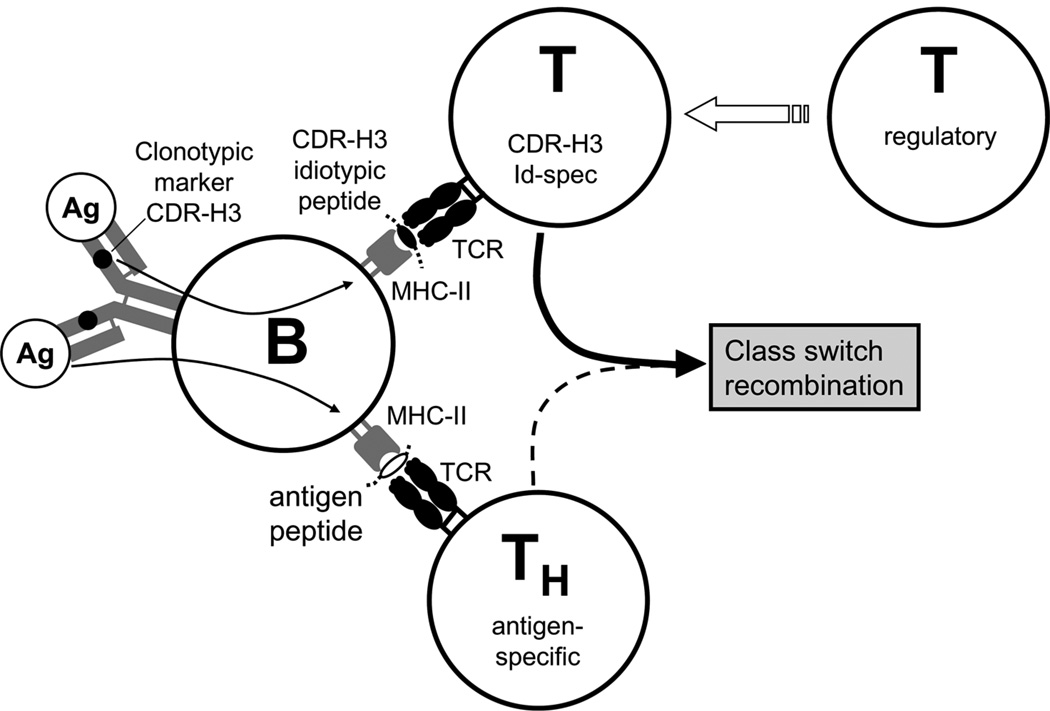

CSR induces a replacement of the constant domains while the variable domains of the initial IgM and the resulting IgG are retained. Therefore, a BCR-related positive clonal selection driven through improved affinity or negative selection as the consequence of new auto-reactive specificities induced by somatic hypermutation [45] would seem to be unlikely explanations for the massive restriction in the repertoire that we have observed in the initial CSR event. However, other experimental findings suggest that T-B cell collaboration during TD responses is not solely mediated by interaction of the TH cell receptor with MHC-II-presented antigenic peptides on B cells. After endocytosis, B cells not only process the bound protein Ag but, at the same time, their intrinsic BCR is also degraded and BCR-derived peptides are presented in a MHC-II bound form on the cell membrane and these peptides can also be recognized by T cells (reviewed in [46]). Processing and presentation of peptides of the intrinsic BCR is strongly enhanced by B cell activation [47]. While presentation of prevalent BCR peptides derived from constant and germline-encoded variable regions induces T cell tolerance [48, 49], T cells specific for rare non-germline peptides remain fully reactive. Such peptides are clonotypic/idiotypic markers (idiotopes) which are somatically generated either during V(D)J recombination, especially in CDR-H3, or by somatic hypermutation in the course of TD immune responses.

It has been argued that idiotope-mediated T-B cell interactions can take place without antigenic stimulation and participate in induction of B cell lymphomas and certain autoimmune diseases [50]. In a transgenic experimental system, idiotypic T-B collaboration provoked a switch to IgG autoantibodies of various specificities [51]. Moreover, application of soluble Id to anti-Id expressing B lymphoma cells directly induced signal transduction as revealed by tyrosine phosphorylation of a variety of intracellular proteins. In vitro experiments demonstrated that idiotope-presentation of this exogenous Id to CD4 T cells is very efficient and that the Id-specifically activated T cells in turn regulate the B lymphoma cells [52]. Hence, we are inclined to assume that endocytosis of the antigen-BCR complex during normal TD immune responses leads to presentation of an array of both antigenic as well as idiotypic BCR peptides, some derived from the sequence of the VH gene segment itself and others from CDR-H3. Through such a double- or multi-specificity, antigen-specific and idiotope-specific T cells could both be involved in CSR. Depending on the T cell repertoire, particular B cell clones could receive mono-, bi- or even multi-specific T cell help or else this help could be suppressed by the action of regulatory T cells (Fig. 3). Support for this latter possibility in particular comes from studies of the TI-2 response to α (1–3) dextran of BALB/c mice (reviewed in [9, 46]). In this response, class switching of the dominating J558 IgM Id is inhibited by the prototypic suppressive regulatory T cell clone 178–4 which has an exquisite specificity for the CDR-H3 peptide of J558 [5, 53].

Figure 3. Possible involvement of CDR-H3 specific T cells in thymus-dependent antigen-induced class switch recombination.

After endocytosis of the BCR-bound Ag, enzymatic degradation not only leads to fragmentation of the Ag but also of the BCR itself. This leads to MHC class II-mediated presentation of antigenic as well as various BCR peptides of constant and variable regions. Peptides of CDR-H3 are clonotypic / idiotypic markers which can be perceived by functionally active anti-idiotypic T cells. Conceivably, such T cells can either promote or impede class switch recombination. Both types of CDR-H3-specific T cells are probably subjected to the influence of regulatory T cells.

If MHC-II-mediated recognition of BCR-derived Id is decisive or even just involved in clone-specific and thus Ag affinity-independent switching to IgG, then this offers one possible simplifying and unifying explanation for the observed repertoire restriction, for the almost complete absence of VH1 family genes among IgG anti-phOx mAb (Table 7), and for the dramatic shortening and concomitant approximation of CDR-H3 during CSR (Fig. 2). In addition, even if it remains possible that the shortening of CDR-H3 in particular responses conveys a unique and preferential binding benefit to the antigen over and above affinity, only the excellent T cell-specificity for particular CDR-H3 peptides could explain the frequently demonstrated recognition and induction of T cell responses to viral peptides artificially grafted into CDR-H3 of autologous Ig [54].

In conclusion, the data presented show that, in a normal and non-transgenic system, the restrictions in the repertoire observed after CSR do not depend solely or even primarily on either an initial repertoire bias or on the affinity of activated early primary IgM. The data strongly support a T cell-dependent clonotypic regulation of immune maturation, apparently reflecting T cell-specificity for BCR-derived peptides, including those of CDR-H3. A test of this hypothesis through examination of mice that differ only in their representation of the CDR-H3 repertoire is now possible [55–57].

Materials and methods

Animals

Female BALB/c (H-2d) mice (Harlan-Winkelmann; Borchen, Germany) were reared under clean conventional conditions in the animal house of the University. Mice were maintained in a 12-h light-dark cycle under standard conditions and were provided with food and water ad libitum. Experimental handling of mice and their care were performed in accordance with relevant institutional and national guidelines and regulations. They were approved by the `Ministry of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Areas´ of the local government of Schleswig-Holstein, permission no. V 312-72241.121-3 (35-3/06).

Antigens

BALB/c mice were immunized either with the type 2 thymus-independent (TI-2) Ag phOx-Ficoll (molar ratio ~ 60) or with the TD Ag phOx-CSA (molar ratio ~ 11) [21]. Natural anti-phOx mAb were tested for reactivity with evolutionary-conserved molecules (all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen; Germany): actin from bovine muscle (no. A3653), myosin from rabbit muscle (no. 70045), dsDNA from calf thymus (no. D1501), tubulin from bovine brain (no. D4925) and keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) from Megathura crenulata (no. H8283).

Immunizations and production of monoclonal antibodies

BALB/c mice (3–4 months old) received primary i.p. immunizations with 25 µg of phOx-Ficoll or 80 µg of phOx-CSA adsorbed to Al(OH)3 and the spleen cells were fused with the non-secretor Ag8.653 myeloma cells by the conventional PEG-mediated hybridization technique after 4 and 7 days, respectively. The natural anti-phOx repertoire of BALB/c mice was analyzed from mAb which were produced from non-immunized animals. These mAb were selected for reactivity with phOx-BSA, but negativity or a much weaker reaction (100-times lower titers) with BSA alone.

Determination of relative affinities of anti-phOx antibodies

As previously described [21], the relative affinities of our antibodies were determined with a hapten-inhibition test in comparison to two prototypic Ox1-idiotypic mAb, namely H11.5 (μ,κ) [58] for IgM and NQ2/16.2 (γ, κ) [59] for IgG antibodies. Briefly, the binding of comparable amounts of anti-phOx Ab to surface-bound phOx-BSA was inhibited with graded concentrations of soluble phOx-caproic acid and those values giving 50% inhibition were taken as relative affinity measures. An affinity factor was generated as the quotient of the relative affinity of H11.5 (μ,κ) for IgM and NQ2/16.2 (γ, κ) for IgG mAb divided by that of a particular Ab. Hence, Ab with an affinity factor of >l exhibited a higher while those with an affinity factor of <l were of lower affinity than NQ2/16.2. The validity of our measurements is indicated by several findings. (i) The present and previous measurements of relative affinities of early and late primary [15, 21] as well as of secondary anti-phOx antibodies (unpublished data) correspond to other published anti-phOx mAb [3]. (ii) Although IdOx1 mAb H11.5 [15] does not perfectly match the VH/VL sequences of Ox1-idiotypic mAb (JH4 instead of JH3 and aspartic acid instead of alanine in position 98 of the heavy chain), all perfectly matching IdOx1 IgM of the present investigation gave identical relative affinities as H11.5. (iii) The affinity of NQ2/16.2 was also checked with fluorescence quenching and gave an almost identical value as obtained by Foote and Milstein [60]. Hence, our determinations of relative affinities are comparable to relevant published data.

Sequencing of antibody V region genes

Sequence analysis of mAb V regions was performed as described [61] with some modifications. Briefly, total RNA of anti-phOx Ab secreting hybrid cell lines was isolated with TRIZOL® (GIBCO-BRL, Eggenstein, Germany) and transcribed into cDNA with SuperScript™ II RNAse H reverse transcriptase (GIBCO-BRL, Eggenstein, Germany) using pd(N)6 random and pd(T)12–18 primers. The VH and VL mRNA sequences were first amplified by PCR using 10 primer sets for each of the VH-regions and 7 primer sets for each of the VL-regions and two forward primers specific for the 3´-end for the first domain of the VH and VL constant regions, respectively. Then, a second semi-nested amplification at 3’-end was performed with the relevant primers coupled with M13 oligonucleotides which were afterwards used for the sequencing reaction (MWG Biotech; Ebersberg, Germany). V region sequences were analyzed with the integrative database VBASE2 (http://www.vbase2.org/) [62].

Accession numbers

GenBank accession numbers for all Ab are indicated in the table legends of each group of antibodies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Hybridoma lines H11.5 and NQ2/16.2 were kindly supplied by C. Berek, Deutsches Rheuma-Forschungszentrum Berlin. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Le328-7/2 to H.Le. and SFBTR22 TPA17 to M.Z.), the Rhön-Klinikum AG (M.Z.) and by the US National Institutes of Health (R01 AI090742, R21 AI088498 and R01 AI48115 to H.W.S).

Abbreviations

- phOx

2-phenyl-oxazolone

- CSR

class switch recombination

- nAb

natural antibody

- CSA

chicken serum albumin

- TD

thymus-dependent

- TI

thymus-independent

- NP

(4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial and commercial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Coutinho A, Kazatchkine MD, Avrameas S. Natural autoantibodies. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:812–818. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgarth N, Tung JW, Herzenberg LA. Inherent specificities in natural antibodies: a key to immune defense against pathogen invasion. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;26:347–362. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berek C, Milstein C. Mutation drift and repertoire shift in the maturation of the immune response. Immunol Rev. 1987;96:23–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mongini PK, Paul WE, Metcalf ES. T cell regulation of immunoglobulin class expression in the antibody response to trinitrophenyl-ficoll. Evidence for T cell enhancement of the immunoglobulin class switch. J Exp Med. 1982;155:884–902. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.3.884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rademaekers A, Specht C, Kölsch E. T-cell enforced invariance of the antibody repertoire in the immune response against a bacterial carbohydrate antigen. Scand J Immunol. 2001;53:240–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelsoe G. In situ studies of the germinal center reaction. Adv Immunol. 1995;60:267–288. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60587-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumgarth N. A two-phase model of B-cell activation. Immunol Rev. 2000;176:171–180. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Antigen-specific memory B cell development. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:487–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes-Carvalho T, Foote J, Kearney JF. Marginal zone B cells in lymphocyte activation and regulation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fairfax KA, Kallies A, Nutt SL, Tarlinton DM. Plasma cell development: from B-cell subsets to long-term survival niches. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu JL, Davis MM. Diversity in the CDR3 region of V(H) is sufficient for most antibody specificities. Immunity. 2000;13:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemke H, Lange H, Berek C. Maternal immunization modulates the primary immune response to 2-phenyl-oxazolone in BALB/c mice. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:3025–3030. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Julin M, Karjalainen K, Makela O. Expression of a mouse immunoglobulin V gene in homozygote and heterozygotes. Ann Immunol (Paris) 1976;127:409–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quan CP, Berneman A, Pires R, Avrameas S, Bouvet JP. Natural polyreactive secretory immunoglobulin A autoantibodies as a possible barrier to infection in humans. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3997–4004. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.3997-4004.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lange H, Solterbeck M, Berek C, Lemke H. Correlation between immune maturation and idiotypic network recognition. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2234–2242. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baumgarth N, Herman OC, Jager GC, Brown L, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA. Innate and acquired humoral immunities to influenza virus are mediated by distinct arms of the immune system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2250–2255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu YJ, Zhang J, Lane PJ, Chan EY, MacLennan IC. Sites of specific B cell activation in primary and secondary responses to T cell-dependent and T cell-independent antigens. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2951–2962. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sverremark E, Fernandez C. Unresponsiveness following immunization with the T-cell-independent antigen dextran B512. Can it be abrogated? Immunology. 1998;95:402–408. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maizels N, Bothwell A. The T-cell-independent immune response to the hapten NP uses a large repertoire of heavy chain genes. Cell. 1985;43:715–720. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vos Q, Lees A, Wu ZQ, Snapper CM, Mond JJ. B-cell activation by T-cell-independent type 2 antigens as an integral part of the humoral immune response to pathogenic microorganisms. Immunol Rev. 2000;176:154–170. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lange H, Zemlin M, Tanasa RI, Trad A, Weiss T, Menning H, Lemke H. Thymus-independent type 2 antigen induces a long-term IgG-related network memory. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:2847–2860. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McHeyzer-Williams MG, McLean MJ, Lalor PA, Nossal GJ. Antigen-driven B cell differentiation in vivo. J Exp Med. 1993;178:295–307. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brezinschek HP, Foster SJ, Dorner T, Brezinschek RI, Lipsky PE. Pairing of variable heavy and variable kappa chains in individual naive and memory B cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:4762–4767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosner K, Winter DB, Tarone RE, Skovgaard GL, Bohr VA, Gearhart PJ. Third complementarity-determining region of mutated VH immunoglobulin genes contains shorter V, D, J, P, and N components than non-mutated genes. Immunology. 2001;103:179–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reche PA, Reinherz EL. Prediction of peptide-MHC binding using profiles. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;409:185–200. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-118-9_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clarke SH, Staudt LM, Kavaler J, Schwartz D, Gerhard WU, Weigert MG. V region gene usage and somatic mutation in the primary and secondary responses to influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Immunol. 1990;144:2795–2801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacob J, Przylepa J, Miller C, Kelsoe G. In situ studies of the primary immune response to (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl. III. The kinetics of V region mutation and selection in germinal center B cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1293–1307. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shih TA, Roederer M, Nussenzweig MC. Role of antigen receptor affinity in T cell-independent antibody responses in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:399–406. doi: 10.1038/ni776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shih TA, Meffre E, Roederer M, Nussenzweig MC. Role of BCR affinity in T cell dependent antibody responses in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:570–575. doi: 10.1038/ni803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berek C, Ziegner M. The maturation of the immune response. Immunol Today. 1993;14:400–404. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dal Porto JM, Haberman AM, Kelsoe G, Shlomchik MJ. Very low affinity B cells form germinal centers, become memory B cells, and participate in secondary immune responses when higher affinity competition is reduced. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1215–1221. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linton PL, Decker DJ, Klinman NR. Primary antibody-forming cells and secondary B cells are generated from separate precursor cell subpopulations. Cell. 1989;59:1049–1059. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90761-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linton PJ, Lo D, Lai L, Thorbecke GJ, Klinman NR. Among naive precursor cell subpopulations only progenitors of memory B cells originate germinal centers. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1293–1297. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Decker DJ, Linton PJ, Zaharevitz S, Biery M, Gingeras TR, Klinman NR. Defining subsets of naive and memory B cells based on the ability of their progeny to somatically mutate in vitro. Immunity. 1995;2:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(95)80092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inamine A, Takahashi Y, Baba N, Miyake K, Tokuhisa T, Takemori T, Abe R. Two waves of memory B-cell generation in the primary immune response. Int Immunol. 2005;17:581–589. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bendelac A, Bonneville M, Kearney JF. Autoreactivity by design: innate B and T lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:177–186. doi: 10.1038/35105052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dammers PM, Visser A, Popa ER, Nieuwenhuis P, Kroese FG. Most marginal zone B cells in rat express germline encoded Ig VH genes and are ligand selected. J Immunol. 2000;165:6156–6169. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schelonka RL, Tanner J, Zhuang Y, Gartland GL, Zemlin M, Schroeder HW., Jr Categorical selection of the antibody repertoire in splenic B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1010–1021. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carey JB, Moffatt-Blue CS, Watson LC, Gavin AL, Feeney AJ. Repertoire-based selection into the marginal zone compartment during B cell development. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2043–2052. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song H, Cerny J. Functional heterogeneity of marginal zone B cells revealed by their ability to generate both early antibody-forming cells and germinal centers with hypermutation and memory in response to a T-dependent antigen. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1923–1935. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gatto D, Bauer M, Martin SW, Bachmann MF. Heterogeneous antibody repertoire of marginal zone B cells specific for virus-like particles. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kin NW, Crawford DM, Liu J, Behrens TW, Kearney JF. DNA microarray gene expression profile of marginal zone versus follicular B cells and idiotype positive marginal zone B cells before and after immunization with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Immunol. 2008;180:6663–6674. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tao W, Bothwell AL. Development of B cell lineages during a primary anti-hapten immune response. J Immunol. 1990;145:3216–3222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blier PR, Bothwell A. A limited number of B cell lineages generates the heterogeneity of a secondary immune response. J Immunol. 1987;139:3996–4006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo W, Smith D, Aviszus K, Detanico T, Heiser RA, Wysocki LJ. Somatic hypermutation as a generator of antinuclear antibodies in a murine model of systemic autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2225–2237. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lemke H, Lange H. Generalization of single immunological experiences by idiotypically mediated clonal connections. Adv Immunol. 2002;80:203–241. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(02)80016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Snyder CM, Zhang X, Wysocki LJ. Negligible class II MHC presentation of B cell receptor-derived peptides by high density resting B cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:3865–3873. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eyerman MC, Zhang X, Wysocki LJ. T cell recognition and tolerance of antibody diversity. J Immunol. 1996;157:1037–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bogen B, Ruffini P. Review: to what extent are T cells tolerant to immunoglobulin variable regions? Scand J Immunol. 2009;70:526–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2009.02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holmoy T, Vartdal F, Hestvik AL, Munthe L, Bogen B. The idiotype connection: linking infection and multiple sclerosis. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Munthe LA, Os A, Zangani M, Bogen B. MHC-restricted Ig V region-driven T-B lymphocyte collaboration: B cell receptor ligation facilitates switch to IgG production. J Immunol. 2004;172:7476–7484. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobsen JT, Lunde E, Sundvold-Gjerstad V, Munthe LA, Bogen B. The cellular mechanism by which complementary Id+ and anti-Id antibodies communicate: T cells integrated into idiotypic regulation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:515–522. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Austrup F, Kodelja V, Kucharzik T, Kölsch E. Characterization of idiotype-specific I-Ed-restricted T suppressor lymphocytes which confine immunoglobulin class expression to IgM in the anti-alpha (1- > 3) Dextran B 1355 S response of BALB/c mice. Immunobiology. 1993;187:36–50. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(11)80244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaghouani H, Steinman R, Nonacs R, Shah H, Gerhard W, Bona C. Presentation of a viral T cell epitope expressed in the CDR3 region of a self immunoglobulin molecule. Science. 1993;259:224–227. doi: 10.1126/science.7678469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ippolito GC, Pelkonen J, Nitschke L, Rajewsky K, Schroeder HW., Jr Antibody repertoire in a mouse with a simplified D(H) locus: the D-limited mouse. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;987:262–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb06058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schelonka RL, Ivanov II, Jung DH, Ippolito GC, Nitschke L, Zhuang Y, Gartland GL, et al. A single DH gene segment creates its own unique CDR-H3 repertoire and is sufficient for B cell development and immune function. J Immunol. 2005;175:6624–6632. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ippolito GC, Schelonka RL, Zemlin M, Ivanov II, Kobayashi R, Zemlin C, Gartland, et al. Forced usage of positively charged amino acids in immunoglobulin CDR-H3 impairs B cell development and antibody production. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1567–1578. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Apel M, Berek C. Somatic mutations in antibodies expressed by germinal centre B cells early after primary immunization. Int Immunol. 1990;2:813–819. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.9.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Griffiths GM, Berek C, Kaartinen M, Milstein C. Somatic mutation and the maturation of immune response to 2-phenyl oxazolone. Nature. 1984;312:271–275. doi: 10.1038/312271a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Foote J, Milstein C. Kinetic maturation of an immune response [see comments] Nature. 1991;352:530–532. doi: 10.1038/352530a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lange H, Kobarg J, Yazynin S, Solterbeck M, Henningsen M, Hansen H, Lemke H. Genetic analysis of the maternally induced affinity enhancement in the non-Ox1 idiotypic antibody repertoire of the primary immune response to 2-phenyloxazolone. Scand J Immunol. 1999;49:55–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Retter I, Althaus HH, Munch R, Müller W. VBASE2, an integrative V gene database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D671–D674. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.