Abstract

Nonsegmented negative-sense RNA viruses (mononegaviruses) control viral gene expression largely through a transcription gradient such that promoter-proximal genes are transcribed more abundantly than downstream genes. For some paramyxoviruses, naturally occurring differences in the levels of efficiency of transcription termination by various gene end (GE) signals provide an additional level of regulation of gene expression. The first two genes (NS1 and NS2) of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are particularly inefficient in termination. We investigated whether altering the termination efficiency (TE) of these two genes in infectious recombinant virus would affect transcription of promoter-proximal and promoter-distal genes, production of viral proteins, and viral replication in cell culture and in the respiratory tract of mice. Recombinant RSVs were constructed with mutations that increased or decreased the TE of the NS1 GE signal, increased that of the NS2 GE signal, or increased that of both signals. Increasing the TE of either or both GE signals resulted in decreased production of the related polycistronic readthrough mRNAs, which normally arise due to the failure of the viral polymerase to recognize the GE signal. This was accompanied by a small increase in the levels of monocistronic NS1 and NS2 mRNAs. Conversely, decreasing the TE of the NS1 GE increased the production of readthrough mRNAs concomitant with a decrease of monocistronic NS1 and NS2 mRNA levels. These changes were reflected in the levels of NS1 and NS2 protein. All of the mutant viruses displayed growth kinetics and virus yields similar to wild-type recombinant RSV (rA2) in both HEp-2 and Vero cells. In addition, all mutants grew similarly to rA2 in the upper- and lower-respiratory tract of BALB/c mice, though some of the mutants displayed slightly decreased replication. These data suggest that the natural inefficiencies of transcription termination by the NS1 and NS2 GE signals do not play important roles in controlling the magnitude of RSV gene expression or the efficiency of virus replication. Furthermore, while changes in the TE of a GE signal clearly can affect the transcription of its gene as well as that of the one immediately downstream, these changes did not have a significant effect on the overall transcriptional gradient.

Human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most important viral etiologic agent of pediatric respiratory disease worldwide (6). RSV is the prototype member of the genus Pneumovirus of the family Paramyxoviridae. Its genome consists of a single, negative-sense RNA of 15,222 nucleotides (nt) (for strain A2) encoding 10 major subgenomic mRNAs and 11 viral proteins (6). The viral gene order is 3′-NS1-NS2-N-P-M-SH-G-F-M2-L-5′.

Synthesis of mRNA by RSV follows the stop-start model of transcription characteristic of Mononegavirales (10). By this model, the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase enters the genome at the single promoter located at the 3′ leader region and transcribes the linear array of genes by a sequential termination-reinitiation mechanism during which the polymerase remains template bound. Transcription yields a series of subgenomic mRNAs. The polymerase sometimes dissociates irreversibly from the template, primarily at the gene junctions (15), resulting in a polar gradient such that promoter-proximal genes are transcribed more abundantly than promoter-distal genes (9).

Termination and reinitiation during sequential transcription by mononegaviruses are directed by short consensus gene start (GS) and gene end (GE) signals that flank each gene. The RSV GS signal, 3′-CCCCGUUUA(U/C), is highly conserved among RSV genes except for L, which has the somewhat divergent signal 3′-CCCUGUUUUA (differences shown in underlined letters) (6). The RSV GE signal is a semiconserved sequence 12 or 13 nt in length (7). Inefficient termination by the polymerase at the various GE signals leads to the production of readthrough mRNAs that are characteristic of RSV and of mononegaviruses in general. These readthrough mRNAs are exact copies of two or more adjacent genes and their intervening intergenic regions and account for approximately 10% of total mRNA in RSV-infected cells. Only the first open reading frame (ORF) of a readthrough mRNA would be expected to be translated efficiently, given the general inefficiency of eukaryotic ribosomes for initiation at internal ORFs. Therefore, production of polycistronic mRNAs would have the effect of reducing the amount of translatable mRNA of each downstream gene represented in the particular readthrough mRNA (6). On the other hand, readthrough of a gene junction spares the polymerase from template dissociation; thus, inefficient transcription termination of upstream genes may play an important role in gene regulation by providing more polymerase to downstream genes, resulting in increased levels of expression.

Minigenome systems have been used to study the differences in transcription termination among the RSV gene junctions. Entire gene junction sequences (GE-intergenic-GS) from RSV were inserted in a dicistronic minigenome, with the results confirming that termination is most efficient at the gene junction of SH-G, moderately efficient at the gene junctions of N-P, P-M, M-SH, and G-F, and least efficient at NS1-NS2, NS2-N, F-M2, and M2-L (11). To isolate the effects on transcription termination due to the GE sequences, the various GE signals were placed in the context of the same gene junction (N-P). These studies showed that the NS1 and NS2 GEs were approximately 60% as efficient as the other GE signals and that the M and N GE signals were most efficient at directing termination (18). These observations concerning the relative efficiencies of the various RSV GE signals are generally consistent with what would be predicted on the basis of the pattern of monocistronic and readthrough mRNAs in RSV-infected cells (9). However, for reasons that are unknown, the level of readthrough mRNA observed with the minigenome systems is higher, and in some cases much higher, than that observed in authentic infection (11, 13), indicating that the minigenome results do not precisely reflect the regulation of RSV transcription.

The 12- or 13-nt sequence of the GE signal of all RSV genes can be divided into three regions: (i) the first 5 nt, 3′-UCAAU-5′, which are conserved exactly among all of the genes, with the exception of the NS2 GE, which is 3′-UCAUU-5′ (difference shown as an underlined letter), followed by (ii) a poorly conserved A/U-rich region of 3 or 4 nt and by (iii) a highly conserved tract of four to five uridylate residues (7). Polyadenylation is thought to occur by reiterative copying of this short tract of U residues (7, 18, 19). Previous studies using dicistronic minigenomes have shown that mutations in any of these three regions can significantly affect the efficiency of transcription termination, though the central region appeared to be the least sensitive (13, 22). More recently, it has been suggested that the single nucleotides preceding and following the 12- to 13-nt GE signal also affect the efficiency of termination (12).

Since all previous studies of RSV GE signals have been performed using synthetic minigenome systems, which can give artifactually high levels of readthrough as noted above, it was important to investigate the importance of transcription termination in regulating RSV viral gene expression in the context of an authentic viral infection. In the present study, we created six recombinant viruses that have altered NS1 and/or NS2 GE signals and studied the effects on transcription of NS1 and NS2, transcription of downstream genes, RNA replication, protein expression, plaque morphology, and virus replication in vitro and in the respiratory tract of mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction and virus recovery.

Construction of a cDNA copy of the RSV antigenome under the control of a T7 promoter has been described previously (8). Site-directed mutagenesis of the NS1 and/or NS2 GE signals was performed according to the method of Kunkel et al. (17). Briefly, single-stranded DNA was prepared from a pGEM 7Z(-) plasmid containing an AatII-HindIII fragment of the antigenome (23) that included the 3′ end of the antigenome through nt 1491 (pGEM-NS). Five mutants were generated using the following 5′-phosphorylated oligonucleotides for the mutagenesis reaction: for 1-SH, 5′-TCTGTTAAGTTTTtaATTAACTAATGGTG-3′ (nt 585 to 557); for 1-UAU, 5′-TCTGTTAAGTTTTtatTTAACTAATGGTG-3′ (585 to 557); for 1-GGU, 5′-TCTGTTAAGTTTTtggTTAACTAATGGTG-3′ (585 to 557); for 1-N/M, 5′-TCTGTTAAGTTTTtTATTAACTAATGG-3′ (585 to 559); and for 2-N/M, 5′-CCTTAAGTTTTttAtTaACTATAAT-3′ (1105 to 1082). The numbers in parentheses indicate the nucleotide positions in the antigenome cDNA, lowercase letters indicate mutated nucleotides, underlining indicates the nucleotides in the virus nomenclature, and the italic letter for 2-N/M indicates an inserted thymidine. A sixth mutant, designated 12-N/M, was generated by using the 1-N/M and 2-N/M primers together in the same mutagenesis reaction. The resulting AatII-HindIII fragment for each mutant was introduced back into the antigenome cDNA, and the nucleotide sequence of the fragment was confirmed.

The recovery of recombinant RSV (rRSV) was performed as described previously (8) with HEp-2 cells that were simultaneously infected with three focus-forming units per cell of a recombinant vaccinia virus (MVA strain) expressing T7 RNA polymerase (MVA-T7) and transfected with a mixture of plasmids encoding the RSV N, P, L, and M2-1 proteins and either wild-type or mutant antigenome cDNA plasmids. The presence of the expected mutations was confirmed in recombinant virus by reverse transcription-PCR of viral genomic RNA and nucleotide sequencing.

Northern blot and Western blot analysis.

HEp-2 cells were infected in three independent experiments with wild-type or GE mutant viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3 PFU per cell. In each experiment, an aliquot of each inoculum was analyzed by plaque assay to confirm the titer. Cells were collected at 16 h postinfection and divided into two aliquots: one was harvested using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) to isolate total intracellular RNA, and the other was processed for protein analysis by the addition of 2× gel sample buffer (100 mM Tris-Cl [pH 6.8], 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20% glycerol, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 200 mM dithiothreitol) and centrifugation through QIAshredders (Qiagen). RNA samples were subjected to electrophoresis in 1.5% (for NS1 and NS2 probes) and 1.0% (for N and F probes) agarose gels containing formaldehyde, transferred to nitrocellulose, and hybridized with 32P-labeled double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) probes prepared by random hexamer labeling (using Megaprime DNA labeling systems) (Amersham Life Science) of NS1, NS2, N, and F RSV ORFs.

For Western blot analysis, cell extracts were electrophoresed through 4 to 20% (for RSV structural proteins) or 16% (for NS1 and NS2) polyacrylamide Tris-glycine gels. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Optitran; Schleicher & Schuell) (0.2 μm) which were incubated with rabbit antibodies raised against purified RSV virions (5) or with rabbit anti-peptide antibodies specific to NS1 and NS2 (1). Bound antibodies were visualized by secondary incubation with horseradish peroxidase-coupled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibodies (Kirkegaard & Perry) followed by chemiluminescence (New England Nuclear).

Growth of rRSV in vivo.

BALB/c mice(6 to 8 weeks old) in groups of five (or of four in the case of rA2) were infected with 106 PFU of a given GE mutant virus or wild-type rA2 in a volume of 0.1 ml administered intranasally under light anesthesia. An aliquot of each inoculum was analyzed by plaque assay to confirm the titer. Mice were sacrificed 3, 4, and 5 days postinfection, and their nasal turbinates and lungs were harvested for virus titration as described previously (28). Mean titers were calculated for each virus and site of infection, and the peak titers were compared irrespective of day postinfection; thus, each value was derived on the basis of results for 12 (in the case of rA2) or 15 (in the case of the GE mutant viruses) animals. The statistical significance of differences in the mean viral titer for each group of mice was analyzed using the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test.

RESULTS

Recovery of rRSV containing mutations in the NS1 and/or NS2 GE signals.

To examine how RSV gene expression and replication might be affected by changes in the efficiency of transcription termination of one or two individual genes, we engineered six rRSVs containing mutations introduced into the NS1 and/or NS2 GE signals (Fig. 1). The NS1 and NS2 genes were chosen for several reasons: (i) their signals have been found to be the least efficient in termination, providing the opportunity to examine the effect of increasing as well as decreasing the efficiency of termination; (ii) neither the NS1 gene nor the NS2 gene, singly or in combination, is essential for RSV replication in vitro, and hence, reductions in their level of expression might affect growth but should not be lethal (16, 23, 24); and (iii) they are the first two genes in the RSV genome and therefore provide the best possible test of the idea that alterations in termination efficiency (TE) of an upstream gene might alter the efficiency of expression of all genes farther downstream.

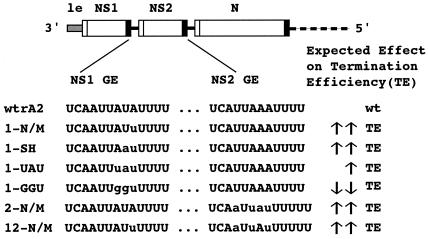

FIG. 1.

Mutations in the NS1 and/or NS2 GE signals designed to alter TE. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to introduce alterations in the NS1 GE (nt 557 to 585) and the NS2 GE (nt 1082 to 1105). Mutated bases are shown in lowercase letters. The recombinant virus designation is written on the left: 1, mutations engineered in the NS1 GE; 2, mutations engineered in the NS2 GE; 12, mutations engineered in both the NS1 and NS2 GEs; N/M, the GE signal found naturally in the N and M genes; SH, the GE signal found naturally in the SH gene. The expected effects on TE efficiency indicated to the right (up arrow, increased TE; down arrow, decreased TE; single arrow, small effect; double arrows, large effect) were determined on the basis of previous studies with minigenomes (see the text). wt, wild type.

The six mutants were designed as follows (Fig. 1): the GE signal of the NS1 gene was replaced with the naturally occurring GE signal of the N and M genes (which is identical for those two genes), yielding the virus designated 1-N/M, or with the naturally occurring GE signal of the SH gene, yielding the 1-SH virus (Fig. 1). These two versions of the GE signal have been shown previously in minigenome systems to be the most efficient at terminating transcription (11, 18). Two other mutants were designed on the basis of other previous observations made with minigenomes (13): nt 7 to 9 of the NS1 GE signal (AUA in negative sense) were replaced with either UAU, yielding the 1-UAU virus, or with GGU, yielding the 1-GGU virus. The 1-UAU virus would be expected to terminate NS1 transcription with an efficiency intermediate between those of the wild-type NS1 GE and the N/M or SH GE, and the 1-GGU virus would be expected to terminate NS1 transcription very poorly (at a level far below that observed for any naturally occurring GE signal) (13). In addition, we replaced the GE signal of the NS2 gene with the N/M GE signal, yielding the 2-N/M virus, and replaced the GE signals of both the NS1 and NS2 genes with the N/M GE signal, yielding the 12-N/M virus. The swaps involving the NS2 GE resulted in the addition of an extra nucleotide to the GE of the NS2 gene, altering its length from 12 to 13 nt. Each of the mutant viruses was readily recovered, and the mutations were found to be stable after several passages, as determined by sequencing reverse transcription-PCR products prepared from viral genomic RNA (data not shown).

Northern blot analysis of viral RNA expression.

We investigated whether the alterations of the NS1 and/or NS2 GE signals had an effect on the steady-state levels of viral RNAs. HEp-2 cells were infected individually with each of the mutant rRSVs in three independent experiments. Total cellular RNA was isolated 16 h postinfection and subjected to Northern blot analysis using dsDNA probes representing the NS1, NS2, N, or F genes (representative data for NS1, NS2, and N are shown in Fig. 2). The time of 16 h postinfection was chosen on the basis of the results of a preliminary experiment that compared the various viruses at different times postinfection and showed that their kinetics of RNA accumulation were very similar and that 16 h was an appropriate time point (data not shown). The signals for each species of mRNA were quantified by phosphorimagery. To determine the TE at the NS1 GE or NS2 GE, the phosphorimager intensity (in arbitrary units) for each monocistronic mRNA was divided by those for all subgenomic mRNAs containing the gene of interest as the first gene and the quotient was multiplied by 100 [e.g., NS1 GE TE = NS1/(NS1 + NS1-NS2 + NS1-NS2-N) × 100]. Thus, a TE of 100% indicates that termination was 100% efficient and that all of the product was monocistronic mRNA. In the present study, the TEs observed for the wild-type NS1 and NS2 GE signals in the context of an authentic RSV infection were 85 and 89%, respectively, and thus were substantially higher than those observed with the various minigenome systems, for which the values of TE ranged from 60% (18) to 15 to 40% (11). In a separate calculation, the phosphorimager intensities for the monocistronic NS1, NS2, N, and F mRNAs were normalized to that of the genome-size band in the same gel lane for each virus-probe combination. This determined the molar amount of each mRNA relative to the genome-size band, which consists of genome and the much less abundant antigenome.

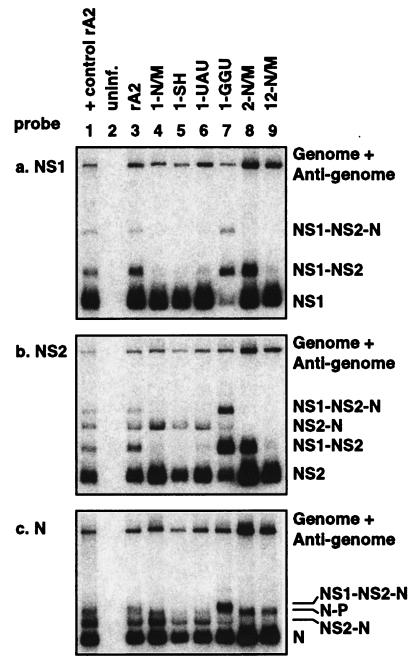

FIG. 2.

RSV RNA expression by the GE mutant viruses. Total intracellular RNA was isolated from HEp-2 cells 16 h postinfection and subjected to Northern blot analysis with 32P-labeled dsDNA probes directed against NS1 (a), NS2 (b), or N (c). Monocistronic and readthrough mRNA species are indicated on the right. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments. uninf., uninfected.

Figure 2a shows representative results with the NS1 probe. Mutation of the NS1 GE signal to make it match the more efficient N/M or SH GE signal, as seen with the 1-N/M, 1-SH, and 12-N/M mutants, resulted in a nearly complete absence of NS1-containing readthrough mRNA (Fig. 2a, lanes 4, 5, and 9) and a very high TE compared to that of wild-type rA2 (96 to 97% for the mutant viruses versus 85% for the wild type). The 1-UAU virus also exhibited an increased TE (95%). However, as expected, it was not as efficient as the 1-N/M and 1-SH viruses, as evidenced by the faint NS1-NS2 readthrough band (Fig. 2a, lane 6). With these mutants, there was a trend toward higher molar ratios of monocistronic NS1 compared to those for wild-type rA2, consistent with the idea that increasing the TE of the NS1 GE signal would result in a higher yield of monocistronic mRNA at the expense of readthrough mRNA.

Conversely, the 1-GGU virus, in which the NS1 GE signal was mutated to be less efficient, displayed a striking decrease in TE at the NS1 GE (41% compared to 85% for wild-type rA2). This resulted in a substantial reduction in the accumulation of monocistronic NS1 mRNA (the relative molar amount was 37% of that of wild-type rA2) and relatively more readthrough mRNAs (Fig. 2a, lane 7). However, the increase in NS1-containing readthrough mRNAs appeared to be insufficient to account for the decrease in monocistronic NS1 mRNA, which might mean that the readthrough mRNAs are less stable than monocistronic NS1 mRNA.

Analysis with the NS2 probe confirmed that increasing the TE of the NS1 GE, as seen with the 1-N/M, 1-SH, 1-UAU, and 12-N/M viruses, sharply reduced the accumulation of NS1-NS2 readthrough mRNA (Fig. 2b, lanes 4, 5, 6, and 9). This was associated with a marginal increase in the accumulation of monocistronic NS2 mRNA, consistent with the idea of a shift from the synthesis of NS1-NS2 readthrough mRNA into monocistronic NS1 and NS2 mRNAs. Conversely, decreasing the TE of the NS1 GE signal, as seen with the 1-GGU mutant, resulted in a shift from monocistronic NS1 and NS2 mRNAs into readthrough mRNAs (Fig. 2b, lane 7; the NS1 and NS2 monocistronic mRNAs were reduced to a TE of 37 and 53%, respectively, of that of wild-type rA2).

Mutation of the NS2 GE signal to make it match the more efficient N/M GE signal, as seen with the 2-N/M and 12-N/M mutants, increased the TE of the NS2 GE (99% compared to 89% for wild-type rA2), resulting in essentially a complete loss of NS2-N readthrough mRNA (Fig. 2b, lanes 8 and 9; also, Fig. 2c, lanes 8 and 9).

Analysis with the N probe (Fig. 2c) showed that the faint NS1-NS2-N readthrough mRNA that is characteristic of wild-type rA2 was absent in the 1-N/M, 1-SH, and 1-UAU viruses (lanes 4, 5, and 6), which is an expected consequence of increasing the TE of the NS1 GE signal. In contrast, the 1-GGU virus produced a large amount of NS1-NS2-N mRNA but very little NS2-N mRNA (Fig. 2c, lane 7), which would be consistent with decreased initiation at the NS2 gene due to increased readthrough of the NS1-NS2 gene junction. The 2-N/M and 12-N/M viruses produced little NS1-NS2-N or NS2-N mRNA (Fig. 2c, lanes 8 and 9), effects that are consistent with an increased TE for the NS2 GE signal. We were unable to detect a consistent increase in the expression of N mRNA, which might have been an expected consequence of increased TE at the GE immediately upstream. This might represent a technical limitation in detecting small increases in an abundant mRNA. Both viruses did express an increased level of N-P mRNA (Fig. 2c, lanes 8 and 9), suggesting that there was indeed an increase in transcription initiation at the N gene due to increased TE at the adjoining NS2 GE signal.

Analysis with the F probe (data not shown) was performed to determine whether altering the TE of promoter-proximal genes would affect the efficiency of transcription of promoter-distal genes. As noted above, it is difficult to reliably monitor small changes in the accumulation of an abundant mRNA. Given this caveat, we were unable to detect any consistent change in the accumulation of F mRNA in response to changes in the TE of the GE signals of NS1 and/or NS2.

Quantitation of the Northern blots such as that shown in Fig. 2 also showed that the overall level of both genome-size RNA and mRNA was consistently higher for the 2-N/M and 12-N/M mutants than that seen with wild-type rA2 and the other mutants (data not shown). The amount of genome-size RNA was increased four- to fivefold compared to that seen with wild-type rA2 and the other mutants, and the amount of mRNA was increased two- to threefold. This suggests that both RNA replication and transcription were increased for the 2-N/M and 12-N/M viruses. The lesser magnitude of the increase for mRNA compared to that of genome-size RNA is not surprising, since an increase in transcription might lag behind an increase in the level of the template.

Western blot analysis of viral protein expression.

We next investigated whether the alterations in viral RNA expression caused by the GE mutations affected viral protein expression. Whole-cell extracts from the samples used as described above for RNA isolation were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis using either a rabbit polyclonal antiserum directed against gradient-purified RSV that detects the RSV structural proteins N, P, M, and G (Fig. 3a) or a rabbit antiserum raised against a peptide consisting of the 12 C-terminal amino acids of NS2 that cross-reacts with NS1 (Fig. 3b). The overall accumulation of viral protein in the particular experiment shown in Fig. 3 was somewhat higher for the 1-N/M and 1-UAU viruses than that seen with wild-type rA2, while that of 1-SH was somewhat lower; these differences were not consistent and reflected experimental variability. The overall level of viral protein accumulation was modestly but consistently elevated for the 2-N/M and 12-N/M viruses, which is consistent with the elevated accumulation of RNA for these two viruses. For each mutant virus, the levels of N, P, M, and G relative to each other were similar to that seen with wild-type rA2 (Fig. 3a).

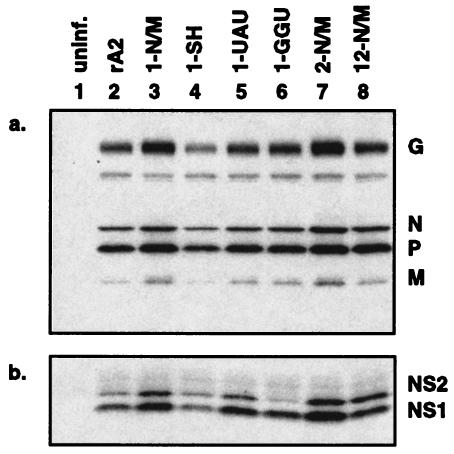

FIG. 3.

Expression of RSV proteins by the GE mutant viruses. Total cell extracts of HEp-2 cells were harvested 16 h postinfection and analyzed by Western blot analysis with antiserum directed against purified virions (a) or antiserum specific to the NS1 and NS2 proteins (b). Major viral proteins are indicated on the right. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments. uninf., uninfected.

In contrast, there were noticeable differences in NS1 and NS2 expression between the mutant rRSVs and rA2 (Fig. 3b). To minimize the effects of experimental variability, we compared the relative expression levels of NS1 and NS2 within each gel lane. This was expressed as a ratio (NS1/NS2), recognizing that this value does not reflect relative molar amounts because the relative efficiency of reactivity of the polyclonal serum with NS1 versus NS2 is unknown. Increasing the TE of the NS1 or NS2 GE appeared to slightly increase the expression of NS2 relative to that of NS1: specifically, mutants 1-N/M, 1-SH, 1-UAU, and 2-N/M had NS1/NS2 ratios of 1.76, 1.65, 2.12, and 1.82, respectively, compared to 2.41 for rA2. These results were consistent with a reduction in the NS1-NS2 readthrough mRNA in favor of monocistronic NS1 and NS2 mRNAs: such a shift probably would not change the expression of NS1, since that ORF is 5′ proximal in both the NS1-NS2 and NS1 mRNAs, but it should increase the expression of NS2, which otherwise would not be efficiently expressed in the NS1-NS2 mRNA. Conversely, the 1-GGU mutant, in which the TE of the NS1 GE was decreased approximately 50% compared to that of wild-type rA2, expressed very little NS2 protein and exhibited a NS1/NS2 ratio of 6.22 (Fig. 3b, lane 6). The 2-N/M virus had an NS1/NS2 ratio of 1.82, suggesting that increasing the TE of the NS2 gene increased its expression. The 12-N/M virus, in which the TE efficiency was increased for both GE signals, had the highest relative level of expression of NS2 (with a ratio of 1.09) and thus appeared to exhibit additive effects of the 1-N/M and 2-N/M viruses, as might be expected. Thus, the mutant viruses differed considerably in the relative expression of the NS1 and, in particular, the NS2 protein.

Growth of GE mutant viruses in vitro.

Teng and Collins have previously shown that abolition of NS1 or NS2 expression in rRSV results in pinpoint plaque morphology and decreased growth kinetics in HEp-2 cells (reference 23 and results not shown). However, the various GE mutant viruses did not appear to exhibit any consistent difference in plaque size or morphology compared to that of wild-type rA2 in HEp-2 or Vero cells (not shown).

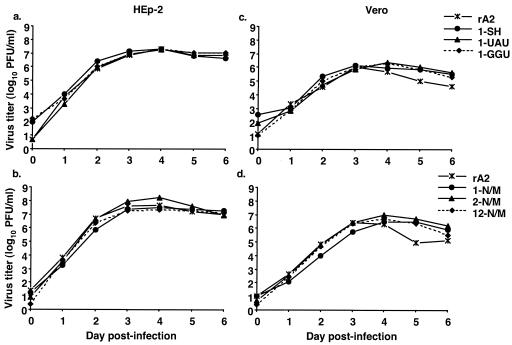

We next examined whether the different GE mutant viruses differed with regard to the kinetics and magnitude of replication in HEp-2 cells, which are capable of producing interferon, or in Vero cells, which lack the structural genes for interferons α and β (Fig. 4). Monolayer cultures were infected with rA2 or individual GE mutant viruses at a MOI of 0.01. Supernatants were harvested daily for 6 days postinfection, and virus titers were determined on the corresponding cell line. All the mutant viruses grew with essentially the same kinetics and to final viral titers similar to those of rA2 in both HEp-2 (Fig. 4a and b) and Vero cells (c and d). Thus, the differences seen in RNA and protein expression by the GE mutant viruses involving the NS1, NS2, and N genes were not reflected in growth of the viruses in vitro.

FIG. 4.

Growth of GE mutant viruses in HEp-2 and Vero cells. Duplicate cultures of HEp-2 (a and b) or Vero (c and d) cells were infected with mutant or wild-type rRSVs at an MOI of 0.01 PFU/cell. Supernatants were harvested daily, and viral titers were determined by plaque assay using the cell line from which the supernatants were derived. Plaques were visualized by immunostaining with anti-F monoclonal antibodies (21), and the mean titers (log10 PFU/ml) are shown.

Replication of GE mutant viruses in the respiratory tracts of BALB/c mice.

To compare the abilities of the various GE mutant viruses to infect and replicate in the respiratory tract of mice, we infected groups of BALB/c mice intranasally with 106 PFU of each virus. The mice were sacrificed 3, 4, and 5 days postinfection, nasal turbinates and lungs were harvested, and virus replication in these tissues was analyzed by plaque titration. The mean titer was calculated for each group for each day, and the peak titer (irrespective of day postinfection) is shown in Table 1. The 1-N/M virus was modestly, but significantly, attenuated in both the upper and lower respiratory tracts compared with rA2 (Table 1). The 1-SH, 1-UAU, and 1-GGU viruses replicated somewhat less efficiently than the wild type in both anatomical locations (except for the 1-SH virus in the lungs), although the reduced replication was statistically significant only in the case of the 1-UAU virus in the lungs. The 2-N/M virus appeared to replicate slightly better than rA2 in both the nasal turbinates and lungs, though the differences were not statistically significant. The 12-N/M mutant appeared to have a phenotype intermediate between the 1-N/M and 2-N/M viruses: it was attenuated in the upper respiratory tract, a difference that was statistically significant, but replicated similarly to rA2 in the lower respiratory tract. Taken together, replication of the GE mutant rRSV in the respiratory tracts was very similar to that of the wild type and was not greatly affected by changes in the efficiency of TE of the NS1 and/or NS2 GE signals.

TABLE 1.

Replication of GE mutant rRSVs in the upper and lower respiratory tracts of BALB/c micea

| Virus | Nasal turbinates

|

Lungs

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean peak virus titer ± SEM (log10 PFU/g of tissue)b | Statistical groupingc | Mean peak virus titer ± SEM (log10 PFU/g of tissue)b | Statistical groupingc | |

| rA2 | 4.0 ± 0.23 | AB | 4.5 ± 0.10 | ABC |

| 1-N/M | 3.3 ± 0.13 | C | 3.9 ± 0.07 | D |

| 1-SH | 3.8 ± 0.04 | BC | 4.6 ± 0.03 | AB |

| 1-UAU | 3.6 ± 0.11 | BC | 4.1 ± 0.10 | CD |

| 1-GGU | 3.7 ± 0.11 | BC | 4.5 ± 0.07 | ABC |

| 2-N/M | 4.5 ± 0.06 | A | 4.8 ± 0.12 | A |

| 12-N/M | 3.3 ± 0.09 | C | 4.3 ± 0.08 | BC |

BALB/c mice in groups of 15 were administered 106 PFU of the indicated virus intranasally under light anesthesia on day 0, and 5 mice from each group were sacrificed on days 3, 4, and 5 postinfection. Nasal turbinates and lungs were harvested, and virus titers were determined by plaque assay. The lower limits of detection in the upper and lower respiratory tracts were 2.0 and 1.7 log10 PFU/g, respectively.

Mean peak titer for each virus irrespective of day.

Mean peak virus titer was assigned to statistically similar groups (groups A to D for nasal turbinate and lung vitus titers) by the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test (P < 0.05). Values within a column that share a common letter are not significantly different, whereas those that do not are significantly different.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the effect of changes in the TE of the NS1 and/or NS2 GE signals in rRSV in the context of an authentic RSV infection. The panel of mutants included three in which the TE of the NS1 GE signal was increased (1-N/M, 1-SH, and 1-UAU viruses), one in which the TE of the NS1 signal was decreased (1-GGU virus), one in which the TE of the NS2 signal was increased (2-N/M virus), and one in which the TE was increased for both the NS1 and NS2 genes (2-N/M virus). The panel of mutants exhibited a range of TE in the respective mutant GE signal(s) from 41 to 99%, which considerably exceeded that found naturally for wild-type rA2 and thus provided a good opportunity to detect possible effects.

Increasing the TE of either NS1 (1-N/M, 1-SH, 1-UAU, and 12-N/M viruses) or NS2 (2-N/M and 12-N/M viruses) greatly reduced the amount of readthrough across the corresponding gene junction and usually resulted in a very modest increase in the accumulation of the monocistronic mRNA for the gene in question as well as for its immediate downstream neighbor. The one exception was that we were unable to consistently detect an increase in the accumulation of N mRNA in response to increasing the TE of the NS2 gene (2-N/M and 12-N/M viruses). This likely reflects a technical limitation in detecting a small increase in the accumulation of an abundant mRNA. However, an increase in the more easily monitored N-P readthrough mRNA was apparent for both viruses (Fig. 2c, lanes 8 and 9), suggesting that increased initiation at the N gene did occur despite our inability to detect it convincingly at the level of monocistronic N mRNA. Conversely, decreasing the TE of the NS1 GE signal (1-GGU virus) resulted in a dramatic increase in readthrough mRNA and a clear decrease in the accumulation of NS1 and NS2 monocistronic mRNAs. Thus, increasing or decreasing the TE of a GE signal resulted in an interconversion between monocistronic and readthrough mRNAs.

The two viruses in which the TE of the NS2 gene was increased (2-N/M and 12-N/M viruses) exhibited a consistent, substantial increase in the level of accumulation of mRNA and genome-size RNA. The basis for this effect remains to be established, although we hypothesize that the increased TE of NS2 resulted in a small increase in transcriptional initiation at the next downstream gene, namely, N. As noted above, we were unable to consistently demonstrate an increase in the relative molar amount of monocistronic N mRNA for these two viruses (N mRNA was increased in absolute terms, reflecting the overall increase in RNA synthesis, but the values normalized to genome-size RNA were not increased). However, we did observe a clear increase in the N-P readthrough mRNA that would be consistent with increased N gene transcription. It is widely thought that the expression of N protein is strongly rate limiting for mononegavirus RNA replication (20). Thus, even a small increase in the expression of N might initiate a cycle in which RNA replication is incrementally increased, which in turn would cause a further small increase in the transcription of all genes, including N, which in turn would cause a further small increase in RNA replication. The effect on transcription was somewhat less than that of RNA replication, which might be expected since transcription would lag behind amplification of the template.

The TEs of upstream genes also have the potential to affect the transcriptional gradient and hence the amount of polymerase moving down the genome, with the possibility of global effects on downstream gene transcription. The transcriptional gradient results from irreversible polymerase falloff occurring primarily at the gene junctions. Falloff at a given gene junction presumably would be avoided if the polymerase transcribed through to produce a readthrough mRNA. Thus, a high TE would reduce readthrough at that junction, expose a larger fraction of polymerase complexes to the possibility of falloff, and thus have the potential to reduce transcription of downstream genes (except for the immediate downstream neighbor, for which transcriptional initiation would be increased due to the shift from readthrough to termination-reinitiation at the adjacent GE signal). Conversely, a lower TE results in increased readthrough across the junction, sparing the polymerase from falloff at that particular junction and potentially increasing the amount of polymerase available for downstream genes. Two of the GE mutants should have been particularly appropriate for observing such changes, namely, the 12-N/M mutant, with increased TE for both the NS1 and NS2 GE signals, and the 1-GGU mutant, which had a drastically reduced TE for the NS1 GE signal. However, we were unable to detect a reproducible increase or decrease in the expression of the downstream F gene. It is not possible to conclude that such changes did not occur, but apparently any such changes were below the level of detection given the already high levels of monocistronic mRNA. However, if such changes were significant biologically, they should be reflected in changes in virus replication in vitro and in vivo, as discussed below.

The most important aspect of the present study was the opportunity to examine the effects of the various GE mutations on the growth of complete infectious virus in vitro and in vivo, providing a more authentic test of biological significance than is possible with minigenomes. In vitro, the GE mutant viruses were essentially indistinguishable from wild-type RSV with regard to growth kinetics, virus yield, and plaque size both in interferon-α/β-competent (HEp-2) and interferon-deficient (Vero) cells. In vivo, the GE mutant viruses replicated in the respiratory tract of mice with efficiencies similar to that of wild-type RSV. The maximum observed difference in mean peak titer between any GE mutant virus and wild-type rA2 was 0.7 log10 (1-N/M mutant, upper respiratory tract), and in most cases the modest differences that were observed were not statistically significant.

Teng and others have shown that completely abolishing expression of the NS1 and/or NS2 genes in rRSV resulted in virus with substantially delayed growth kinetics and lower final viral titers and which display pinpoint plaque morphology in HEp-2 cells (4, 23). In addition, rRSV with deletions in the NS1 and/or NS2 genes grow poorly in the respiratory tracts of mice, cotton rats, and chimpanzees (27) (M. N. Teng and P. L. Collins, unpublished data). Surprisingly, in the present study, changes in the level of expression of NS1 or NS2 had little or no effect on replication in vitro or in vivo. This was true, for example, even in the case of the strongly reduced expression of NS2 protein by the 1-GGU mutant (Fig. 3, lane 6). These observations imply that while expression of the NS1 and NS2 proteins is essential for efficient replication, the level of expression of NS1 and NS2 by wild-type RSV apparently is in excess and is not rate limiting. This was somewhat unexpected, since NS1 and NS2 are the first and second genes in the gene order, positions that have been assumed to reflect a requirement for high expression. This apparently is not the case for the NS1 and NS2 genes of RSV.

Close inspection of the in vivo replication data suggests that some subtle trends might exist. For example, the three viruses in which the TE of the NS1 GE signal was increased as the sole mutation (1-N/M, 1-SH, and 1-UAU viruses) each appeared to exhibit slightly reduced replication in vivo (with the exception of the 1-UAU virus in the lungs), although this was significant statistically only in the case of the 1-N/M virus. Decreased growth would be consistent with reduced polymerase flow due to increased TE. However, one would then have expected to observe the converse effect, that of increased growth, for the 1-GGU virus, since this would be consistent with increased polymerase flow due to reduced TE, but this was not observed. Interpretation of the in vivo growth patterns of the 2-N/M and 12-N/M viruses was complicated, because the increased TE of the NS2 GE signal appeared to have the unanticipated effect of increased transcriptional initiation of the N gene, as discussed above. Thus, while the 12-N/M virus had increased TE at two GE signals, providing the best case for evaluating possible effects, this expected negative effect on growth might be offset by the possible improved growth due to an increase in N gene transcription.

These observations provide some direction for further experiments to investigate the effects of GE signals on polymerase flow down the RSV genome. For example, it is clear that altering the TE of a GE signal can affect both the gene in question and the one immediately downstream. It also is clear that one must distinguish between rate-limiting genes, as N is thought to be, and those that are not rate limiting, as NS1 and NS2 appear to be. In particular, if one wishes to observe effects on polymerase flow on the expression of genes that are further downstream than the next neighbor, it is essential to have the changes in TE involve genes that are not rate limiting, such as the NS1 and NS2 genes of the present study, or perhaps to use nonessential inserted supernumerary gene cassettes and to avoid adjacency to rate-limiting genes such as N. Finally, the present study suggests that RSV replication in vitro is insensitive to small changes in viral gene expression and that replication in the respiratory tract of mice might be more sensitive.

In conclusion, it has been shown for a number of mononegaviruses that transcriptional attenuation occurs at the gene junctions (2, 3, 11, 14, 18, 25, 26). The present study shows that the efficiency of TE can directly affect the efficiency of expression of the gene in question and its immediate downstream neighbor. The biological significance of the effects depends on whether expression of one or both of the genes in question is rate limiting for RSV RNA replication or growth. It also has been suggested that differences in TE for upstream genes might affect the polarity of the transcriptional gradient and hence the efficiency of expression of genes that are further downstream. However, the results of the present study indicate that if such effects occurred, they generally were of insufficient magnitude to have consistent significant global effects on macromolecular synthesis or virus growth. This study also indicated that the natural inefficiencies of the NS1 and NS2 GE signals do not contribute significantly to controlling the magnitude of RSV replication in vitro or in vivo. Thus, the suboptimal nature of these GE signals likely does not represent a subtle control mechanism; rather, it might be that these GE signals are suboptimal because the efficiency of their functioning is not critical to RSV replication and hence the acquisition of mutations that modestly decrease their efficiency is tolerated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Whitehead for assistance with the animal studies, statistical analysis, and critical reading of the manuscript, Kathy Hanley for statistical analysis, Chris Hanson for help with sequencing, and Brian Murphy and Kirsten Spann for reviewing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atreya, P. L., M. E. Peeples, and P. L. Collins. 1998. The NS1 protein of human respiratory syncytial virus is a potent inhibitor of minigenome transcription and RNA replication. J. Virol. 72:1452-1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr, J. N., S. P. Whelan, and G. W. Wertz. 1997. Role of the intergenic dinucleotide in vesicular stomatitis virus RNA transcription. J. Virol. 71:1794-1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bousse, T., T. Matrosovich, A. Portner, A. Kato, Y. Nagai, and T. Takimoto. 2002. The long noncoding region of the human parainfluenza virus type 1 F gene contributes to the read-through transcription at the M-F gene junction. J. Virol. 76:8244-8251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchholz, U. J., S. Finke, and K. K. Conzelmann. 1999. Generation of bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) from cDNA: BRSV NS2 is not essential for virus replication in tissue culture, and the human RSV leader region acts as a functional BRSV genome promoter. J. Virol. 73:251-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukreyev, A., S. S. Whitehead, B. R. Murphy, and P. L. Collins. 1997. Recombinant respiratory syncytial virus from which the entire SH gene has been deleted grows efficiently in cell culture and exhibits site-specific attenuation in the respiratory tract of the mouse. J. Virol. 71:8973-8982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins, P. L., R. M. Chanock, and B. R. Murphy. 2001. Respiratory syncytial virus, p. 1443-1485. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 7.Collins, P. L., L. E. Dickens, A. Buckler-White, R. A. Olmsted, M. K. Spriggs, E. Camargo, and K. V. Coelingh. 1986. Nucleotide sequences for the gene junctions of human respiratory syncytial virus reveal distinctive features of intergenic structure and gene order. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:4594-4598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins, P. L., M. G. Hill, E. Camargo, H. Grosfeld, R. M. Chanock, and B. R. Murphy. 1995. Production of infectious human respiratory syncytial virus from cloned cDNA confirms an essential role for the transcription elongation factor from the 5′ proximal open reading frame of the M2 mRNA in gene expression and provides a capability for vaccine development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11563-11567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins, P. L., and G. W. Wertz. 1983. cDNA cloning and transcriptional mapping of nine polyadenylylated RNAs encoded by the genome of human respiratory syncytial virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:3208-3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emerson, S. U. 1987. Transcription of vesicular stomatitis virus. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 11.Hardy, R. W., S. B. Harmon, and G. W. Wertz. 1999. Diverse gene junctions of respiratory syncytial virus modulate the efficiency of transcription termination and respond differently to M2-mediated antitermination. J. Virol. 73:170-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harmon, S., and G. Wertz. 2002. Transcriptional termination modulated by nucleotides outside the characterized gene end sequence of respiratory syncytial virus. Virology 300:304-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harmon, S. B., A. G. Megaw, and G. W. Wertz. 2001. RNA sequences involved in transcriptional termination of respiratory syncytial virus. J. Virol. 75:36-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He, B., and R. A. Lamb. 1999. Effect of inserting paramyxovirus simian virus 5 gene junctions at the HN/L gene junction: analysis of accumulation of mRNAs transcribed from rescued viable viruses. J. Virol. 73:6228-6234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iverson, L. E., and J. K. Rose. 1981. Localized attenuation and discontinuous synthesis during vesicular stomatitis virus transcription. Cell 23:477-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin, H., X. Cheng, H. Z. Zhou, S. Li, and A. Seddiqui. 2000. Respiratory syncytial virus that lacks open reading frame 2 of the M2 gene (M2-2) has altered growth characteristics and is attenuated in rodents. J. Virol. 74:74-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunkel, T. A., J. D. Roberts, and R. A. Zakour. 1987. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 154:367-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo, L., R. Fearns, and P. L. Collins. 1997. Analysis of the gene start and gene end signals of human respiratory syncytial virus: quasi-templated initiation at position 1 of the encoded mRNA. J. Virol. 71:4944-4953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuo, L., R. Fearns, and P. L. Collins. 1996. The structurally diverse intergenic regions of respiratory syncytial virus do not modulate sequential transcription by a dicistronic minigenome. J. Virol. 70:6143-6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamb, R. A., and D. Kolakofsky. 2001. Paramyxoviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 1305-1340. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Strauss (ed.), Fields virology, vol. 1. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 21.Murphy, B. R., A. V. Sotnikov, L. A. Lawrence, S. M. Banks, and G. A. Prince. 1990. Enhanced pulmonary histopathology is observed in cotton rats immunized with formalin-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or purified F glycoprotein and challenged with RSV 3-6 months after immunization. Vaccine 8:497-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutherland, K. A., P. L. Collins, and M. E. Peeples. 2001. Synergistic effects of gene-end signal mutations and the m2-1 protein on transcription termination by respiratory syncytial virus. Virology 288:295-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teng, M. N., and P. L. Collins. 1999. Altered growth characteristics of recombinant respiratory syncytial viruses which do not produce NS2 protein. J. Virol. 73:466-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teng, M. N., S. S. Whitehead, A. Bermingham, M. St. Claire, W. R. Elkins, B. R. Murphy, and P. L. Collins. 2000. Recombinant respiratory syncytial virus that does not express the NS1 or M2-2 protein is highly attenuated and immunogenic in chimpanzees. J. Virol. 74:9317-9321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tokusumi, T., A. Iida, T. Hirata, A. Kato, Y. Nagai, and M. Hasegawa. 2002. Recombinant Sendai viruses expressing different levels of a foreign reporter gene. Virus Res. 86:33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wertz, G. W., R. Moudy, and L. A. Ball. 2002. Adding genes to the RNA genome of vesicular stomatitis virus: positional effects on stability of expression. J. Virol. 76:7642-7650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitehead, S. S., A. Bukreyev, M. N. Teng, C. Y. Firestone, M. St Claire, W. R. Elkins, P. L. Collins, and B. R. Murphy. 1999. Recombinant respiratory syncytial virus bearing a deletion of either the NS2 or SH gene is attenuated in chimpanzees. J. Virol. 73:3438-3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitehead, S. S., C. Y. Firestone, P. L. Collins, and B. R. Murphy. 1998. A single nucleotide substitution in the transcription start signal of the M2 gene of respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate cpts248/404 is the major determinant of the temperature-sensitive and attenuation phenotypes. Virology 247:232-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]