Abstract

Objective

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α1 (nAChRα1) was recently identified as a functional cell receptor for urokinase, a potent atherogenic molecule. Here, we test the hypothesis that nAChRα1 plays a role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.

Methods

Apolipoprotein E-deficient mice were initially fed a Western diet for 8 wks. Plasmid DNA encoding scramble RNA (pscr) or siRNA (psir2) for nAChRα1 was injected into the mice (n = 16) using an aortic hvdrodvnamic gene transfer protocol. Four mice from each group were sacrificed 7 days after the DNA injection to confirm the nAChRα1 gene silencing. The remaining mice continued on a Western diet for an additional 16 wks.

Results

The nAChRα1 was up-regulated in aortic atherosclerotic lesions. A 78% knockdown of the nAChRα1 gene resulted in remarkably less severe aortic plaque growth and neovascularization at 16 wks (both P< 0.05). In addition, significantly fewer macrophages (60% less) and myofibroblasts (80% less) presented in the atherosclerotic lesion of the psir2-treated mice. The protective mechanisms of the nAChRα1 knockdown may involve up-regulating interferon-γ/Y box protein-1 activity and down-regulating transforming growth factor-β expression.

Conclusions

The nAChRα1 gene plays a significant role at the artery wall, and reducing its expression decreases aortic plaque development.

1. Introduction

Atherosclerotic vascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Western countries, accounting for more than one-third of all deaths each year [1]. Known atherosclerotic risk factors include dyslipidemia, hypertension, cigarette smoking, diabetes, infection, systemic inflammation, homocysteine, and chronic kidney disease [1,2]. Atherosclerosis is initiated by endothelial cell injury and accompanied by an accumulation of lipoproteins in the vessel wall. This leads to the development of a chronic inflammatoryfibrotic process involving: macrophages, T cells, and smooth muscle ceels/myofibroblasts. A key event in the development of atherosclerotic plaque is the focal intimal migration of circulating blood monocytes to the vessel wall, and their subsequent activation [3]. Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) are two pivotal regulators of the atherosclerotic process, both with pro-and anti-atherogenic actions [4].

Recent literature has found that nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR)-mediated pathological angiogenesis plays an important role in the growth of atherosclerotic plaque [5]. The nAChR mediates pro-atherosclerotic effects of two classical ligands: nicotine and acetylcholine [6,7]. Urokinase, an important angiogenic and atherogenic molecule, has been newly identified as an alternative ligand for the muscle-type nAChR [8]. The muscle-type nAChR consists of the specific assembly of five polypeptide subunits (α1, β1, γ, δ, or ε). The binding domain of the receptor involves the interaction between the α1 subunits (nAChRα1) and the remaining subunits (β1, γ, δ, or ε). Upon ligation, the muscle-type nAChR is activated and serves as a ligand-gated calcium/sodium ion channel, known to mediate signal transduction at the neuromuscular junction. Silencing the nAChRα1 subunit can fully abrogate the function of the entire muscle type nAChR [8]. Although the nAChRα1 was originally discovered in the neuromuscular junction, it has since been identified in a variety of non-neuromuscular cell types including: immune cells, renal interstitial fibroblasts, glomerular cells, tubular epithelial cells, respiratory epithelial cells, non-small lung cancer cells, vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and smooth muscle specific α actin-positive myofibroblasts [8–10]. However, the expression and function of the nAChRα1 in the development of atherosclerotic plaque formation has yet to be investigated.

This study was designed to test the hypothesis that nAChRα1 plays a role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. The level of nAChRα1 expression was manipulated using an aorta hydrodynamic gene-silencing approach in an Apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mouse model of atherosclerosis. We found that nAChRα1 was up-regulated by myofibroblasts/smooth muscle cells and macrophages in aortic atherosclerotic lesions. By reducing nAChRα1 expression with RNA interference (RNAi), we observed diminished angiogenesis and aortic plaque development. This suggests that the nAChRα1 gene silencing offers a protective mechanism against atherosclerosis by up-regulating IFN-γ/Y box protein-1 (YB-1) and down-regulating TGF-β activity.

2. Methods

2.1. Antibodies and cDNA reagents

Antibodies used in this study and their sources are: rat monoclonal antibody to nAChRα1 subunit, Covance Co., Berkeley, CA; goat polyclonal antibody to nAChRα1, antibody to OPN (osteopontin), Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA; rat monoclonal antibodies to F4/80, CD11b, Serotec Ltd., Oxford, UK; rabbit anti-human Von Willebrand Factor (vWF), EPO™ horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated monoclonal antibody to αSMA (α-smooth muscle actin), Dako Corp., Carpinteria, CA; fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated monoclonal antibody to β-actin, Sigma-Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO; pan-specific transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) antibody, R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN; rat monoclonal antibody to interferon gamma (IFN-γ), rabbit monoclonal antibody to YB-1 (Y Box Protein-1), Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA. The cDNA reagents used in the in vitro and in vivo RNAi studies are: nAChRα1 siRNA-expressing construct psir2 and matched scramble RNA-expressing construct pscr that were previously described [8].

2.2. Animal studies

Female ApoE−/− mice on a C57BL/6J background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) and fed an atherogenic Western-type diet containing 21% fat and 0.15% cholesterol (TD88137; Harlan-Teklad Laboratories, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) beginning at 8 wks of age [7]. To functionally knockdown aortic nAChRα1 expression, RNAi intervention began at 8 wks following the Western diet. Naked plasmid DNA expressing either hairpin nAChRα1 -siRNA (psir2) or scramble RNA (pscr) was administered (n = 16 per group) via the left renal artery using an aortic hydrodynamic gene transfer protocol modified from a previous publication [11]. Briefly, a midline incision abdominal surgery was performed microscopically under general anesthesia with isoflurane to fully expose the abdominal aorta and left renal artery. The distal end of the left renal artery was ligated and a loose thread loop was placed at the proximal end. Aortic blood flow was temporarily blocked at points above and below the two renal arteries. The right renal artery was transiently clamped during perfusion. Following an instant injection of 200 μg DNA (psir2 or pscr) in 300 μl normal saline, the preset left renal artery loop was immediately tied, and the upper aortic blocking point was first released. After a 5–10 s delay, the lower aortic and the right renal artery blocking points were subsequently released. The left kidney was then removed. After surgery, the mice were maintained on the Western diet. Four mice from each group were sacrificed 7 days after DNA injection to confirm nAChRα1 gene silencing. The remaining mice (n = 12 per group) continued on the Western diet for an additional 16 wks before being sacrificed by exsanguination under general anesthesia. The aorta and serum samples were collected and stored for further analyses. The procedure affected renal function equally in both experimental groups, as indicated by the blood urea nitrogen levels (30.4 ± 6 versus 26.3 ±4, pscr versus psir2, P>0.05, n = 8). Additional aortas from three age-matched female ApoE−/− mice that were fed normal chow served as “normal” controls. All animal studies were approved by the IACUC of Seattle Children’s Research Institute.

2.3. Aorta tissue preparation and serum cholesterol measurement

Following exsanguination, aortas were harvested for formalin Zn2+-fixed paraffin-embedding or Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound-embedding (aorta root), protein (ascending aorta and aortic arch) and RNA (descending aorta) isolation (n=8). Four whole aorta trees from each group were isolated, opened, and pinned for Oil Red O staining. Plasma cholesterol levels were evaluated by a colorimetric assay (Cholesterol/Cholesteroyl Ester Quantitation Kit; BioVision Laboratories, Mountain View, CA).

2.4. Evaluation of aortic atherosclerotic plaque growth

The pinned aortas of four mice from each group were stained with Oil Red O to assess overall severity of the atherosclerotic plaques. Paraffin-embedded aortic root sections (5 μm) were stained with Masson trichrome (Sigma-Aldrich Inc.) to view the general morphological changes and matrix expansion in the atherosclerotic lesions.

2.5. Immunohistology

Paraffin-embedded aortic root sections were stained with primary antibodies to nAChRα1, αSMA, OPN, and YB-1, and were then labeled using a standard ABC kit protocol (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) [12,13]. Immunofluorescent (IF) staining for either F4/80 or vWF was performed on aortic root frozen sections, and identified with AlexaFlour680-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon). Sections lacking primary antibodies were run in parallel as negative controls. In IF double staining, the nAChRα1 was labeled with AlexaFlour680 (red); and the F4/80 or YB-1 identified with FITC (green) fluorescence.

2.6. Morphometric analyses

Histological images were captured using a digital camera linked with the SPOT program, and analyzed using the Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) [8]. For Oil Red O stained aortas, the plaque-occupied area was quantified and the result expressed as a positive percentage of the total area of each aorta tree open surface. Aortic root plaque size was assessed by measuring the plaque areas in 10 sections per mouse. The collagen matrix content of the plaque was evaluated using Masson trichrome-stained aortic root sections, with the results expressed as the percent collagen-occupied area of the plaque. Calcification levels of the aortic wall lesions and aortic valves were evaluated separately on Von Kosa stained sections. For immunolabeling of cells or molecules, results were expressed as a positive percentage of the area of interest (aortic root lesion).

2.7. Western blot analyses

Western blotting (WB) experiments were performed by following standard protocols [14]. Specifically, 80 μg aorta protein samples were separated by a 10–12% SDS-PAGE in non-reducing conditions. Blots were probed with the primary antibodies for nAChRα1, vWF, pan-TGF-β, and IFN-γ, and labeled with the AlexaFluor680-conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Inc.). For protein loading controls, blots were probed with the FITC-conjugated anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody. The stained fluorescent intensities were scanned and analyzed with a Typhoon TRIO Variable Mode Imager (Amersham Bio-sciences).

2.8. Northern blot analyses and real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the aortas using Trizol™ reagent (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Northern blot analyses for αSMA, TGF-β1, OPN, and GAPDH were performed as previously described [13,14]. Real-time PCR was performed for IFN-γ mRNA assessment using a previously published protocol [15]. Real-time surveillance of fluorescence intensity emitted from the amplified product was performed with an iCycler PCR machine (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The amplification efficiency was 101%, and the expected single peak was confirmed in the melting curve. No amplification was found in negative controls. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene for RNA loading correction.

2.9. Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using the Student’s t-test (parametric data of serum cholesterol levels, real-time PCR, Northern and Western blot analyses) or Mann-Whitney U-test (histological data), and the null hypothesis rejected at a P value less than 0.05 (unless specified elsewhere). Results are presented as mean ± 1 S.D. unless stated otherwise.

3. Results

3.1. The nAChRα1 expression in normal and atherosclerotic aortas of ApoE−/− mice

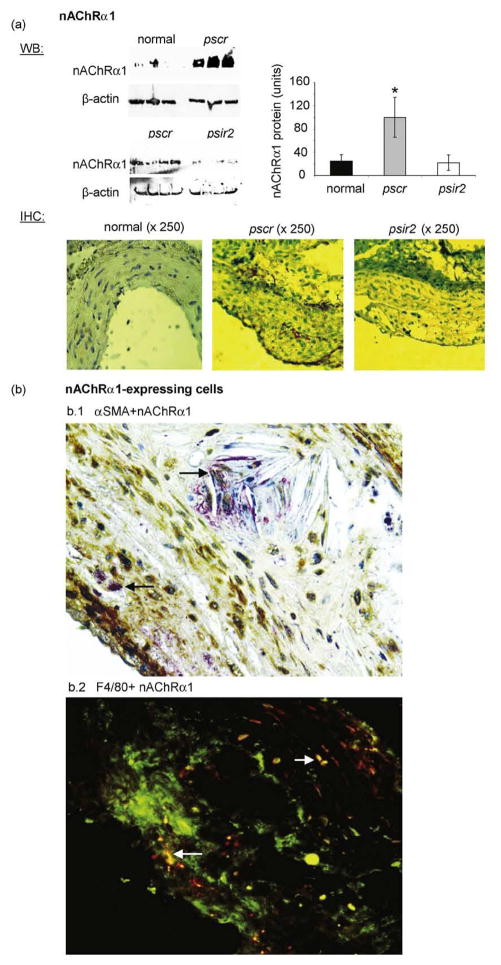

By Western blot analyses, the level of aortic nAChRα1 expression was significantly up-regulated by nearly 4-fold in the pscr-treated mice (24 wks Western diet versus normal diet, n = 3). Knockdown of the nAChRα1 gene was achieved as early as 7 days (76%↓) following DNA injection (Supplementary Fig. 1-online), and aortic nAChRα1 expression in psir2-treated mice remained lower (78%↓) at 16 wks compared to the pscr (n=8, P<0.05) (Fig. 1a). By IHC, nAChRα1 was non-detectable at the normal aorta wall. The nAChRα1 was expressed by some medial smooth muscle cells in the aortic atherosclerotic lesions of the pscr-treated mice fed an atherogenic diet for 24 wks; additional nAChRα1 expression was seen on the cells inside the atherosclerotic plaque (Fig. 1a). No immunodetectable nAChRα1 was present in the aortic plaque in the psir2-treated mice. Inside the atherosclerotic plaque, approximately half of the nAChRα1 expression was co-localized with αSMA+ myofibroblasts (Figure 1b). As identified by double IF staining, nAChRα1-expressing cells included some F4/80+ macrophages, in addition to myofibroblasts.

Fig. 1.

Aortic nAChRα1 expression and silencing in the ApoE−/− mouse model of atherosclerosis. (a) Western blot (WB) analysis for nAChRα1 shows a significant up-regulation after six months on an atherogenic diet and an 80% gene knockdown by the nAChRα1-siRNA expressing vector psir2. The β-actin bands were used to correct for protein loading. The histogram represents the relative band densities analyzed with the NIH image program. *P< 0.05, pscr versus normal (n=3) or psir2 (n = 8). No nAChRα1 expression was detected by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining on a normal aorta wall section. The atherosclerotic aortic lesions (pscr) have de novo nAChRα1 expression. The IHC staining confirms the nAChRα1 silencing effect on the intimal and medial layers of the aortic lesions (psir2). Slides were counter-stained with hemotoxylin. Double IHC (bl) on an aortic root section illustrates co-localized expression of nAChRα1 (red) and αSMA (brown) in an ApoE−/− mouse 6 months post-Western diet. Black arrows point to a couple of the nAChRα1 + myofibroblasts. Double immunofluorescent (IF) staining (b2) illustrates cells that co-express (yellow) nAChRα1 (red) and F4/80 (green) in the aortic root lesions of the pscr-treated mouse. White arrows point to a few nAChRα1+ macrophages. Original magnification: ×400.

3.2. The nAChRα1-silencing reduces aortic plaque growth and neovascularization

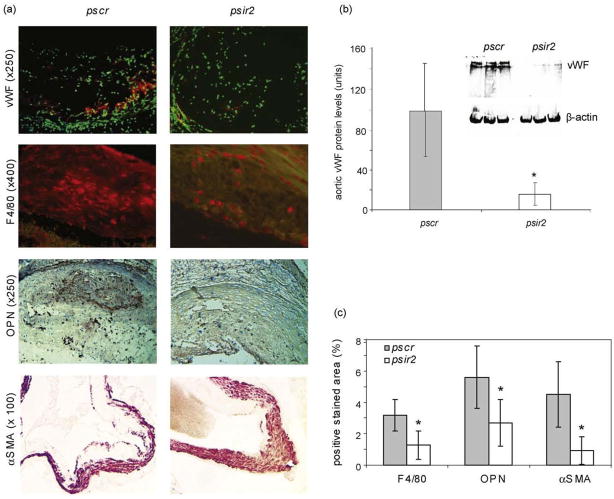

Long-term nAChRα1 gene knockdown after 16 wks dramatically reduced the severity of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mouse aortas (Fig. 2a), despite similar (mean = 559 mg/dl) serum cholesterol levels in the psir2- and pscr-treated mice (P>0.05, n=6). The atherosclerotic lesions of aorta trees stained red-yellow in Oil Red O, were 80% less in the nAChRα1-silenced mice compared to the non-silenced mice (P< 0.05, psir2 versus pscr, n=4). Plaques in aortic roots – where more advanced lesions are known to develop [16] – were examined morphometrically to determine the effect of nAChRα1-silencing on plaque formation in the mice. In the pscr-treated mice, large plaques were visible when the aortic root cross-section was stained with Masson trichrome (Fig. 2b). The plaque size was 43% smaller in the psir2-treated mice (psir2 versus pscr, P< 0.05, n = 6). The collagen matrix content of the plaques, seen in green/blue color on the Masson trichrome stained sections, was 47% less in the nAChRα1-silenced group (29 ±9% versus 54±9%, psir2 versus pscr, P<0.05, n = 6). The neovascularization of aortic plaques, as indicated by vWF IF staining and Western blot analysis (Fig. 3a and b), was 80% less in the nAChRα1 -silenced group (psir2 versus pscr, P<0.05, n = 6). Calcification of aortic root lesions and valves, as measured by Von Kosa staining, was significantly lower in the nAChRα1-silenced mice when compared to the pscr-treated mice (70%↓ in aortic wall and 40%↓ in aortic valves, both P<0.05, n = 6) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Our findings show that the nAChRα1 knockdown greatly diminishes the severity of aortic atherosclerotic lesions.

Fig. 2.

The nAChRα1 silencing inhibits aortic plaque growth, (a) Oil Red O staining in aorta trees of ApoE−/− mice 16 wks after the vector DNA injection. The nAChRα1 silencing (psir2) resulted in a 4-fold reduction in plaque-occupied (yellow-red) percent area of the aorta trees (n = 4). (b) Representative Masson trichrome (M.T.) stained sections of aortic roots 16 wks after the pscr or psir2 DNA injection. In M.T. stain, the green/blue represents collagen matrix, and the red is cytoplasm. Aortic root plaque size was assessed by measuring the plaque areas in 10 sections of each aortic root. *P< 0.05, psir2 versus pscr, n = 6. Mean ± 1 S.D. Note: the cellular-fibrotic cap of the plaque appears similarly intact in both groups on the M.T.-stained sections. The micro-ruler shows a 200 μm bar.

Fig. 3.

Neovascularization and recruitments of macrophages and myofibroblasts are suppressed by nAChRα1 silencing. (a) IF and IHC photomicrographs illustrate plaque vascularity (red fluorescence with nuclear counter-stain in green) and the intimal recruitment of F4/80+ macrophages (red fluorescence) and αSMA+ myofibroblasts (red) 16 wks post-pscr or -psir2 DNA injection. OPN IHC shows a strong expression (red) in both the medial and intimal layers of the diseased aortic wall in the pscr-treated mice. (b) Western blot analysis for vascular endothelial vWF shows an 80% reduction in aorta plaque vascularity 16 wks post-psir2 DNA injection. The vWF Western blot shows two specificbands (lower band = 260 kDa monomer; upper band=vWF polymers). (c) The histogram represents the quantitative data for F4/80, OPN and αSMA staining shown in (a). nAChRα1 silencing (psir2) resulted in a significant reduction in F4/80- (50%↓), αSMA- (80%↓), and OPN-occupied (50%↓) percent area of the aorta root sections. *P< 0.05, psir2 versus pscr, n=6.

3.3. Plaque macrophages and myofibroblasts are reduced in nAChRα1-silenced mice

We next investigated whether cellular components of aortic plaques were affected by the nAChRα1 gene knockdown. F4/80 IF staining revealed a 50% reduction in macrophage content in the aortic root lesions in the psir2-treated mice 16 wks post-nAChRα1 gene silencing (P< 0.05, psir2 versus pscr, n = 6) (Fig. 3a and c). The inhibition of aortic macrophage infiltration was further confirmed by the leukocyte/macrophage marker CD11 b in Western blot analyses, showing a 90% reduction in the aortas of the nAChRα1-silenced mice (100 ±73 versus 6.9 ±7.2 units, pscr versus psir2, P<0.05, n = 4). In addition, osteopontin (OPN), a chemokine that plays an important role in regulating vascular inflammation and calcification [17], was strongly expressed in the aortic lesions (Fig. 3a and c); with the OPN expression level being significantly lower in the nAChRα1-silenced mice (50% reduction, psir2 versus pscr, n=6). The reduced aortic macrophage inflammation in the nAChRα1 -silenced mice was associated with a significant decrease in the presence of plaque αSMA+ myofibroblasts (80% inhibition, psir2 versus pscr, n = 6), as measured by IHC (Figure 3a and c). These data show that nAChRα1 gene knockdown exerts its anti-atherosclerotic effect in the aortic wall by inhibiting OPN expression and macrophage infiltration, and reducing lesion myofibroblast accumulation. In vitro data using a gene silencing strategy to knockdown the nAChRα1 gene in aorta smooth muscle cells (Supplementary Fig. 3) further suggests that the muscle-type nAChR plays a direct role in regulating vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, an important process thought to contribute to the recruitment of atherosclerotic plaque myofibroblasts.

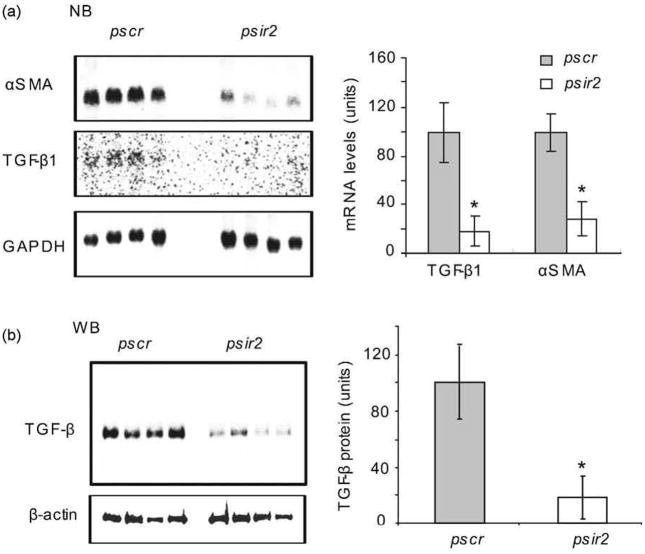

3.4. TGF-β1 and αSMA gene expression is down-regulated by nAChRα1 -silencing

TGF-β is a well-known transcriptional activator of the αSMA gene in myofibroblasts [18]. We sought to determine whether TGF-β is implicated in the nAChRα1-regulated recruitment of αSMA+ myofibroblasts to aortic lesions. Northern blot analyses were performed, comparing aortic TGF-β1 and αSMA mRNA levels of nAChRα1-silenced mice to that of non-silenced mice, 16 wks after DNA delivery. Aortic αSMA mRNA levels were 70% lower in the psir2-treated mice (P<0.05, psir2 versus pscr, n=4) (Fig. 4). This was associated with an 85% reduction of TGF-β1 mRNA in the psir2-treated mice (P< 0.05, psir2 versus pscr, n=4). By Western blot analyses, using a pan-specific TGF-β antibody, aortic TGF-β protein level was 80% lower in the psir2-treated mice compared to the pscr-treated mice (P<0.05, n=4). This data suggests that TGF-β participates in the anti-atherosclerotic actions of the aortic nAChRα1 gene knockdown by regulating αSMA gene transcription.

Fig. 4.

Aortic TGF-β1 and αSMA gene expressions are down-regulated by nAChRα1 silencing. (a) Aorta Northern blot analysis illustrates a significant 3- and 5-fold reduction in αSMA and TGF-β1 mRNA, respectively; this is due to the nAChRα1 silencing seen in the psir2-treated atherosclerotic mice compared to the pscr-treated mice. The histogram represents semi-quantitative results (mean± SD) of Northern blot analysis. The GAPDH mRNA bands were used to correct for RNA loading. *P< 0.05, psir2 versus pscr, n = 4. (b) Aortic pan-TGF-β Western blot analysis illustrates a significant (80%) reduction in total TGF-β protein in the psir2-treated mice compared to the pscr-treated mice. The β-actin bands were used to correct for protein loading. The histogram represents mean band densities.

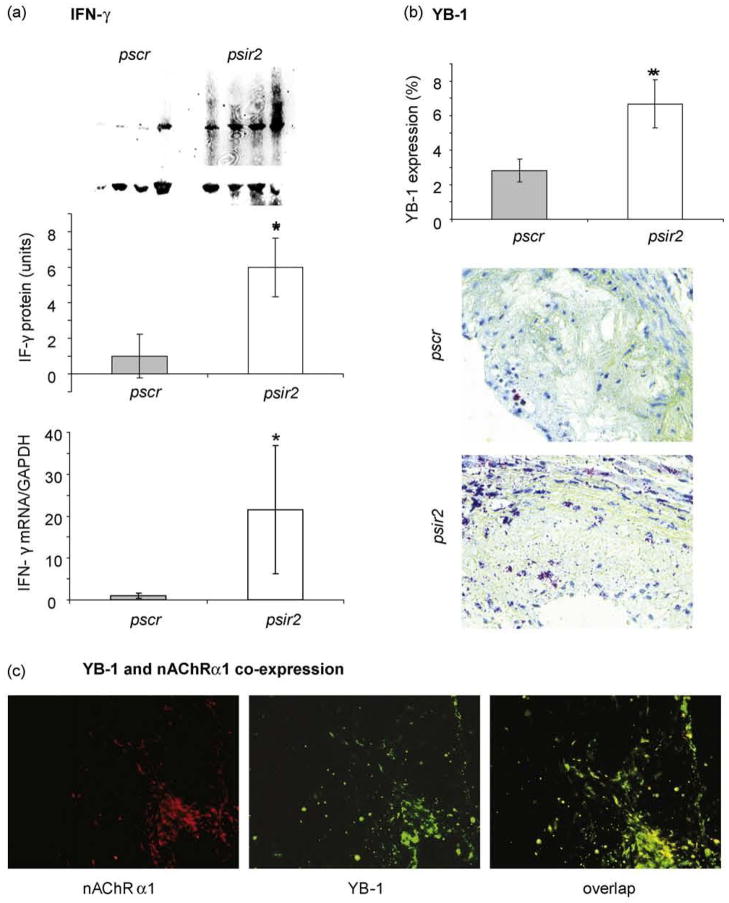

3.5. IFN-γ and YB-1 levels are up-regulated by nAChRα1-silencing

We previously reported that nAChRα1 activation regulates fibroblastic YB-1 gene expression in vitro [8]. Given that YB-1 is involved as a critical mediator of the anti-fibrotic effects of IFN-γ [19], we further investigated whether aortic expression of IFN-γ and YB-1 was affected by nAChRα1 gene knockdown. By Western blot analyses (Fig. 5a), aortic IFN-γ protein (19 kDa) was 6-fold higher in the psir2-treated mice compared to the pscr-treated mice 16 wks post DNA delivery (P<0.05, n = 4). Real-time PCR studies confirmed 20-fold higher IFN-γ mRNA in the psir2-treated mice (P<0.05, psir2 versus pscr, n=5) (Fig. 5a). YB-1 expression of the aortic lesions, as evaluated by IHC, was more than 2-fold higher in the psir2-treated mice (P<0.05, psir2 versus pscr, n=6) (Fig. 5b). In addition, a vast majority of YB-1 protein in the atherosclerotic lesions was nuclear-located, implying YB-1 activation and nuclear translocation. As illustrated by double IF in Fig. 5c, YB-1 was strongly co-expressed with nAChRα1 in an aortic atherosclerotic lesion, suggesting a functional relationship between nAChRα1 and YB-1.

Fig. 5.

Aortic IFN-γ and YB-1 are up-regulated by nAChRα1 silencing. (a) Western blot analysis shows significantly higher levels of IFN-γ in the psir2-treated mice compared to the pscr-treated mice 16 wks post-vector DNA injection. The β-actin bands were used to correct for protein loading. The histogram represents the relative band densities (mean± SD, n = 4). *P< 0.05, psir2 versus pscr. Real-time PCR results confirm significantly higher IFN-γ mRNA in the aortas of the nAChRα1 -silenced mice compared to the pscr group (n = 5). (b) By IHC stain, aorta lesion YB-1 expression (red) was significantly elevated by nAChRα1 silencing (n = 6). Using the Image-Pro Plus program, YB-1 protein was quantified and results expressed as a positive percent area of interest Original magnification: ×400. Counter-stain with hemotoxyline. (c) Double IF staining illustrates nAChRα1 -bearing cells that co-express (yellow overlap image) nAChRα1 (red) and YB-1 (green) in an atherosclerotic aortic lesion of the pscr-treated ApoE−/− mouse fed with a high-fat diet for 6 months. Original magnification: ×250.

4. Discussion

Hyperlipidemia and vascular lipoprotein deposition are thought to instigate the expression of chemokines and inflammatory cytokines on various cell types that co-stimulate chronic macrophage inflammation. This eventually results in the atherogenic effects observed in the ApoE−/− mouse model of atherosclerosis [20]. In the present study, for the first time, we report that nAChRα1 expression is increased in the macrophages and myofibroblasts of the atherosclerotic lesions. The de novo nAChRα1 expression promotes macrophage inflammation, neovascularization, and atherosclerotic lesion formation. The anti-inflammatory action of the nAChRα1 gene knockdown is likely, in part, due to the suppression of OPN expression. The silencing of the nAChRα1 gene was associated with a considerable reduction in the OPN gene and protein expression (seen as early as day 7 and remaining low at 16 wks post-gene silencing). This is in agreement with previous reports that vascular expression and deposition of OPN is an important force that drives atherosclerotic lesion formation, neovascularization, and calcification [17,21]. In addition, nAChRα1 may promote plaque angiogenesis and lesion formation via regulating the activities of a variety of other cytokines/growth factors: IFN-γ, TGF-β, basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) [8], and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [7].

Most cells present in the arterial wall, as a result of vascular damage and subsequent repair, are capable of producing TGF-β and expressing the corresponding TGF-β ligands and receptors [22]. TGF-β is bi-functional, in that it is capable of inducing actions that can be considered both pro- and anti-atherogenic. The effect TGF-β exerts is largely dependent upon whether TGF-β is acting locally at the artery wall (as a pro-fibrotic growth factor) or systemically (as an immunosuppressant) [23]. Systemic inhibition of TGF-β using neutralizing antibodies or gene-modified mice was found to increase atherosclerotic lesion development. In addition, the resulting lesion composition favored inflammatory components rather than collagen content [24]. Conversely, TGF-β has also been shown to contribute to atherosclerosis by acting locally on the artery wall and inducing plaque growth. It is thought that TGF-β contributes to plaque growth by up-regulating the expression of αSMA and collagen genes (directly or indirectly), via plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and other growth factors [25]. In the present study, nAChRα1 gene silencing significantly down-regulated aorta wall TGF-β and αSMA gene and protein expression, resulting in a net protective effect. This suggests that the nAChRα1 gene knockdown approach offsets TGF-β atherogenic action locally at the artery wall.

The inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ is able to elicit both pro-and anti-atherogenic effects [26]. The atherogenic action of IFN-γ is not yet clearly understood; however, it is thought to potentiate macrophage inflammation in atherosclerotic lesions. Despite this, LDLR−/− mice transplanted with bone marrow from IFN-γ-deficient mice exhibited larger atherosclerotic lesions than mice that received bone marrow from IFN-γ-sufficient mice, thereby suggesting a protective role for IFN-γ [27]. IFN-γ can exert its anti-atherogenic effects by inhibiting collagen synthesis in smooth muscle cells/myofibroblasts [19], blocking their proliferation [28], and reducing plaque angiogenesis [29]. The transcription factor YB-1 protein has been shown to be a critical mediator of the anti-fibrotic effects of IFN-γ. YB-1 suppresses αSMA and collagen gene transcription in fibroblasts/vascular smooth muscle cells by occupying the promoters and blocking TGF-β SMAD 2,3 and 4 binding [19]. The knockdown of nAChRα1 resulted in an increased expression of both IFN-γ and YB-1, and was associated with smaller atherosclerotic plaques containing less collagen content. This suggests that up-regulation of YB-1, as a result of nAChRα1-silencing, may have led to mediation of strictly the anti-atherogenic properties of IFN-γ. On the other hand, IFN-γ may exert its anti-angiogenic effect by inducing splice variants of human tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (TrpRS) via an IFN-γ-inducible promoter [29]. Mini TrpRS is known for its potent anti-angiogenic activity, which is accomplished by blocking VEGF-induced endothelial cell proliferation and migration [30].

This study specifically addresses the role of the muscle-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, nAChRα1, on the progression of atherosclerotic plaque growth. The silencing of the nAchRα1 gene hindered the development of aortic atherosclerotic lesions, and was associated with reductions in the density of macrophages, myofibroblasts and plaque vascularity. The present study suggests that the nAChRα1 gene plays a significant role at the artery wall and that reducing its expression offers a potential therapeutic strategy for atherosclerosis, valve calcification, restenosis and vascular remodeling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Scientist Development grant from the American Heart Association National Center (GZ) and the Young Investigator Award from Seattle Children’s Hospital (GZ). We thank the National Institute of Health (NIH)-funded Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center at the University of Washington for its participation in the aorta tree Oil Red O staining. We thank Dr. Allison Eddy (Seattle Children’s Hospital) for her insightful comment and support.

References

- 1.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. New Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss. Circulation. 2006;113:898–918. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assmann A, Mohlig M, Osterhoff M, Pfeiffer AFH, Spranger J. Fatty acids differentially modify the expression of urokinase type plasminogen activator receptor in monocytes. Biochem Bioph Res Commun. 2008;376:196–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson J, Libby P, Hannson GK. Adaptive immunity and atherosclerosis. Clin Immunol. 2010;134:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooke JP. Angiogenesis and the role of the endothelial nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Life Sci. 2007;80:2347–51. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heeschen C, Jang JJ, Weis M, et al. Nicotine stimulates angiogenesis and promotes tumor growth and atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2001;7:833–9. doi: 10.1038/89961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanda Y, Watanabe Y. Nicotine-induced vascular endothelial growth factor release via the EGFR-ERK pathway in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Life Sci. 2007;80:1409–14. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang G, Kernan KA, Thomas A, et al. A novel signaling pathway: fibroblast nicotinic receptor α1 binds urokinase and promotes renal fibrosis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29050–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlisle DL, Liu X, Hopkins TM, et al. Nicotine activates cell-signaling pathways through muscle-type and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20:629–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooke JP, Ghebremariam YT. Endothelial nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and angiogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18:247–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rychahou PG, Evers BM. Hydrodynamic delivery protocols. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;623:189–95. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-588-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang G, Kim H, Xiaohe C, et al. Urokinase receptor modulates cellular and angiogenic responses in obstructive nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1234–53. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000064701.70231.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang G, Kim H, Xiaohe C, et al. Urokinase receptor deficiency accelerates renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1254–71. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000064292.37793.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang G, Kernan KA, Collins SJ, et al. Plasmin(ogen) promotes renal interstitial fibrosis by promoting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: role of plasmin-activated signals. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:846–59. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vetrone SA, Montecino-Rodriguez E, Kudryashova E, et al. Osteopontin promotes fibrosis in dystrophic mouse muscle by modulating immune cell subsets and intramuscular TGF-β. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1583–94. doi: 10.1172/JCI37662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakashima Y, Plump AS, Raines EW, Breslow JL, Ross R. ApoE-deficient mice develop lesions of all phases of atherosclerosis throughout the arterial tree. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:133–40. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiba S, Pkamoto H, Kon S, et al. Development of atherosclerosis in osteopontin transgenic mice. Heart Vessels. 2002;16:111–7. doi: 10.1007/s003800200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desmouliere A, Geinoz A, Gabbiani F, Gabbiani G. Transforming growth factor-β1 induces α-smooth muscle actin expression in granulation tissue myofibroblasts and in quiescent and growing cultures fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:103–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dooley S, Said HM, Gressner AM, et al. Y-box protein-1 is the crucial mediator of antifibrotic interferon-γ effects. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1784–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linton MF, Atkinson JB, Fazio S. Prevention of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice by bone marrow transplantation. Science. 1995;267:1034–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7863332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi F, Akutagawa S, Fukumoto H, et al. Osteopontin induces angiogenesis of murine neuroblastoma cells in mice. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:707–12. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bobik A, Agrotic A, Kanellakis P, et al. Distinct patterns of transforming growth factor-beta isoform and receptor expression in human atherosclerotic lesions. Colocalization implicates TGF-beta in fibrofatty lesion development. Circulation. 1999;99:2883–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.22.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lutgens E, Daemen MJ. Transforming growth factor-beta: a local or systemic mediator of plaque stability. Circ Res. 2001;89:853–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mallet Z, Gojova A, Marchiol-Fournigault C, et al. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta signaling accelerates atherosclerosis and induced an unstable plaque phenotype in mice. Circ Res. 2001;89:930–4. doi: 10.1161/hh2201.099415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otsuka G, Agah R, Frutkin AD, Wight TN, Dichek DA. Transforming growth factor beta-1 induced neointima formation through plasminogen activator inhibitor-1-dependent pathways. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:737–43. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000201087.23877.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLaren JE, Ramji DP. Interferon gamma: a master regulator of atherosclerosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:125–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niwa T, Wada H, Ohashi H, et al. Interferon-gamma produced by bone marrow-derived cells attenuates atherosclerotic lesion formation in LDLR-deficient mice. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2004;11:79–87. doi: 10.5551/jat.11.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansson GK, Hellstraand M, Rymo L, Rubbia L, Gabbiani G. Interferon-γ inhibits smooth muscle cell proliferation and expression of differentiation-specific α-smooth muscle actin in arterial smooth muscle cells. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1595–608. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.5.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J, Shue E, Ewalt KL, Schimmel P. A new gamma-interferon-inducible promoter and splice variants of an anti-angiogenic human tRNA synthetase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:719–27. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wakasugi K, Slike BM, Hood J, et al. A human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase as a regulator of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:173–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012602099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.