Abstract

The quality of care provided by primary care physicians for patients with dementia remains poor, in part because physicians do not provide counseling and education. Local Alzheimer’s Association chapters have the potential to improve the quality of care provided for dementia but are hampered by the lack of referrals by primary care physicians. Many physicians remain unaware of the services available through Alzheimer’s Association chapters but recognize the need to provide support to families, ensure patient safety, and manage behavioral problems. At present, systems to promote referral and communication with local chapters are lacking. Practice redesign may facilitate linkages between practices and Alzheimer’s Association chapters. However, if they are to be adopted and sustained, these linkages must demonstrate a relative advantage to the physicians beyond current care they provide and must be compatible with how care is currently delivered in their practices.

Keywords: Dementia, Alzheimer’s Association, health care delivery, community-based organizations, coordination of care

Introduction

Despite substantial evidence about the appropriate management of Alzheimer’s disease, evaluations of care provided for persons with cognitive impairment and dementia suggest that it is poor. For example, in a recent study of two managed care plans, only 35% of recommended care processes (quality indicators) for dementia were performed.1 When examining the deficiencies, physicians appear to be more comfortable managing the medical components (e.g., ordering tests, discussing and prescribing medications) compared to the counseling and educational aspects of dementia care.2 Many physicians do not have adequate knowledge about community resources and behavioral management to optimally care for patients with dementia. Nor do they have time to provide counseling and support for caregivers.

Alzheimer’s Association chapters can provide services that strengthen patient and family education and facilitate the provision of needed community services. To date, however, the medical community and the local Alzheimer’s Associations chapters have operated independently in parallel systems with little communication or collaboration. Previous studies have identified physicians’ lack of knowledge about, and referral to, community-based services.3, 4 These studies showed that physicians were more likely to refer to medically oriented services (e.g., durable medical equipment) and much less likely to refer to social-model community programs. Yet geriatrics, in general, and dementia care, specifically, rely on developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community.5

Leaders in health care delivery have recognized the importance of linking medical and community-based services through the Chronic Care Model.6 If this model is followed, patients (and their families) become more informed and activated and practice teams are more prepared to be proactive, which should result in improved clinical and functional outcomes. In fact, a number of AA chapters have participated in demonstration projects to strengthen linkages with primary care practitioners who care for patients with dementia. These projects have shown significant positive outcomes, including reported improvements in physician knowledge, practices, and attitudes and improved patient and family caregiver satisfaction and other psychosocial outcomes.7, 8,9, 10 Results are pending for other research and demonstration projects that are testing interventions involving AA chapters.11, 12

The ACOVE-2 intervention is one way of implementing aspects of the Chronic Care Model that has achieved success in improving the quality of care provided for falls and urinary incontinence.2, 13 The ACOVE-2 intervention included:

Efficient collection of condition-specific clinical data, including information collected by non-physicians and automatic orders for simple procedures

Medical record prompts to encourage performance of essential care processes

Patient education materials and activation of the patient’s role in follow-up

Physician decision support and physician education

However, this intervention did not improve the quality of care for dementia, in part because quality indicators related to counseling and care management were not met. Moreover, the penetration of the Chronic Care Model into physicians’ practices has been modest, particularly in small group practices, where the majority of care is provided in the United States.14

Implementing changes to improve the care of older persons in clinical settings has been remarkably difficult. Traditional continuing education programs have been largely ineffective in changing physician behavior.15 Physician barriers have included lack of awareness about appropriate care, disbelief that following guidelines will result in improved patient outcomes, and inability to overcome existing practice habits.16 Additional obstacles include patient factors and environmental factors, such as lack of resources or reimbursement. Perhaps most important, clinicians commonly believe that evidence-based care takes more time and adding time to each encounter is not a viable option. As a result, researchers are developing approaches to improve physician performance by modifying the basic structure of care, often referred to as practice redesign.

Practice redesign can be effective only if embraced by physicians. A commonly used conceptual model to assess uptake of new approaches is derived from Rogers’ work on the diffusion of innovations.17 According to this model, successful innovations must meet the criteria that drive the decision to adopt (relative advantage, complexity, compatibility, trialability, and observability). In other words, if practices are going to adopt new approaches to care, these have to be better than the current approach, they cannot be too complicated for physicians and staff to implement, they must fit in with the way the practice functions, they must be able to be tried on a limited basis before full-scale adoption, and the results of the change must be apparent. To date, little is known about how Alzheimer’s Association services provide relative advantage, can be offered without adding complexity, and are compatible with how care is currently delivered.

To determine whether physicians’ practices can be redesigned to improve the care of persons with dementia by creating linkages with local Alzheimer’s Association chapters, we need a better understanding of what busy primary care physicians perceive as unmet needs in managing patients with dementia and how they would like to communicate with community based organizations. Meeting these needs would improve their practices (i.e., provide a relative advantage) and learning about the optimal communications methods would address the issues of complexity and compatibility.

A logical first step would be to directly ask primary care physicians about these issues. As part of a practice redesign study aimed at improving the quality of dementia care by primary care physicians, we conducted 4 focus groups with a total of 22 physicians from the two participating practices (in Seattle, Washington and San Jose, California) prior to implementation of redesign. The first part of each focus group was used to gather physician input regarding unmet management needs facing patients with cognitive impairment or dementia and their families. Second, the focus groups discussed how the physicians preferred to communicate with the Alzheimer’s Association chapters and receive responses from them. Groups ranged in size from 4 to 7 physicians and lasted approximately 60 – 75 minutes. Sessions were audio taped and later transcribed for analysis. Content analysis techniques were used to identify major themes from each group.

These physicians estimated that about 40% of their patients were over the age of 65 and about 10% of their patients had a cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, or another form of dementia. Only 3 of the 22 physicians reported making five or more referrals to the Alzheimer’s Association in the six months prior to the focus groups, with over half making no referrals. About half of the participants rated such referrals as potentially beneficial to the patient and the physician.

Participants in all groups acknowledged a lack of understanding about the services available. One physician stated, “we have not referred any patients; it’s usually family members who find these resources. We do not know of much.” Focus group participants assumed that the Alzheimer’s Association provided caregiver support, help with home health care, and educational materials. In describing those resources, one physician stated, “I think what they do is give families some information and resources for daycare and nursing homes that have Alzheimer’s settings. I don’t know if there is an actual office to go in and get help.” Physicians also noted that it would be helpful to know about specific services that Alzheimer’s Association chapters are unable to provide.

Unmet needs in caring for dementia patients

The comments of these physicians provided insights about how linkages with the Alzheimer’s Association could improve the care of dementia patients. They described a variety of management needs for patients with cognitive impairment or dementia that were unavailable through traditional medical practices. All groups identified the need for more support for families of patients. Some emphasized the need for support groups while others mentioned case management both for referral services and for comprehensive coordination of health care. Assistance with financial management was noted as a need, particularly if the patient has primary responsibility for such activities in the family. Instrumental support of patients, such as home care services (transportation and shopping), as well as help identifying appropriate living situations were also noted as needs by several participants. Other issues discussed were mental stimulation for patients and physician training about the community resources available for patients at different stages of impairment.

Physicians were queried concerning specific types of unmet needs that previously had been identified in their practices. In response to probes, most of the physicians stated that they were not very knowledgeable about the availability of specific community-based resources that could assist their patients. According to one physician, “We usually contact the pharmaceutical people who refer us to what we need.”

Several specific needs regarding patient safety were also mentioned. First, safety of the living situation was mentioned and home assessments were judged to be critical. As a corollary, physicians noted the need for respite and backup care when the primary caregiver is out of town or at work. Transportation, including unsafe driving, was another safety theme mentioned in all groups. Some physicians said that a better understanding of when to get the DMV involved would enable them to work more effectively with their patients to address such concerns. Management of behavior problems, particularly programs for violent or physically combative patients, was a third theme related to safety. Physicians mentioned that family members often requested help in managing patient wandering and abusive behavior. They were also frustrated in their attempts to get psychiatric help for their patients and some voiced the perception that psychiatrists are not interested in this population, that some are not trained to handle dementia, or that psychiatric help is not available as rapidly as needed. Some expressed concerns about the helpfulness of Adult Protective Services. Finally, medication adherence was discussed, with an acknowledgement of the importance of the caregiver in dispensing medications.

Participants in several groups noted that helping patients and families identify sources for help is complicated by the stigma attached to Alzheimer’s disease. Many noted that patients and their families were reluctant to seek such help, particularly in the early stages of impairment, because of the labeling associated with this condition. Physicians also noted that they occasionally are placed in the position of helping mediate family disagreements about care and felt that such issues are better handled by case managers and those providing legal services.

Finally, the groups discussed unmet needs surrounding decisions regarding nursing home placement and end-of-life issues. Many physicians were pleased with the nursing home alternatives and hospice services available but needed help engaging the patient and family in discussions that would lead to utilizing these services. Physicians described needing assistance to help families make decisions at the end-of-life (e.g., when to initiate a conversation about future planning, how to enlist the support of a social worker who is more sensitive to end-of-life issues, and decision-making with family members who do or do not have power of attorney). Some said that a list of local social workers could help them help their patients.

Partnership and communication with Alzheimer’s Association Chapters

Participants were asked to consider what would constitute the ideal partnership between physician groups and Alzheimer’s Association chapters. All groups mentioned Alzheimer’s Association case management of practice patients with feedback to the referring physician. In particular, multidisciplinary care management meetings were suggested. One physician said, “We would evaluate the patient, then neurology, and then the Alzheimer’s Association can provide us with the kind of help that they can provide. So if we can have the physician, the Alzheimer’s Association and the family sitting together in one room it makes things better.” Another physician described the ideal Alzheimer’s Association partnership as “a multidisciplinary network that you can call on to go to the patient’s house, make an assessment, give us some feedback, and maybe provide a therapist to help the family adjust and help with medications. [The goal would be] to have a team that we can rely on and still be able to be in charge of the medical issues.” A third physician suggested that a mission statement describing the partnership, including specifications of what can and cannot be done within the partnership, would be valuable for both groups.

Most physicians expressed a preference for communication with the Alzheimer’s Association via mail or fax. All groups agreed that a standardized referral form with check boxes would be the best approach. Forms that could be faxed to the Alzheimer’s Association with information about age, insurance coverage, and a checklist of requested services were perceived to be the most effective method for communicating. Physicians thought that referral telephone calls would be inefficient and should be used only in urgent cases.

The majority of physicians desired follow-up communication by fax or e-mail from the Alzheimer’s Association after referrals are made. These reports would be most helpful if they included assessments conducted by the Alzheimer’s Association staff, actions taken, and what services the Alzheimer’s Association chapter can provide. Some of this could be in the form of general pamphlets, but participants also mentioned the value of targeted services for specific patient needs. Some physicians noted that it would be helpful if Alzheimer’s Association reports provided suggestions for what physicians can do to help their dementia patients. In addition, many physicians expressed the desire to be included in the process of Alzheimer’s Association -generated referrals and evaluations. They also mentioned that seminars that offer continuing medical education credits would be a great way to educate physicians about Alzheimer’s Association services.

Building on this knowledge

These comments from primary care physicians indicate that although dementia is uncommon in their practices, they have substantial unmet needs in caring for this disorder. Although local Alzheimer’s Association chapters can meet many of these needs, physicians are often unaware of the services that the chapters can provide. Thus, a major step that the Alzheimer’s Association could undertake would be to launch an awareness campaign targeting primary care physicians and their staffs about which patients should be referred and when. The services that can be provided by the Alzheimer’s Association chapters should be communicated clearly and promoted as being beneficial to patients while making it easier for physicians to provide high quality care.

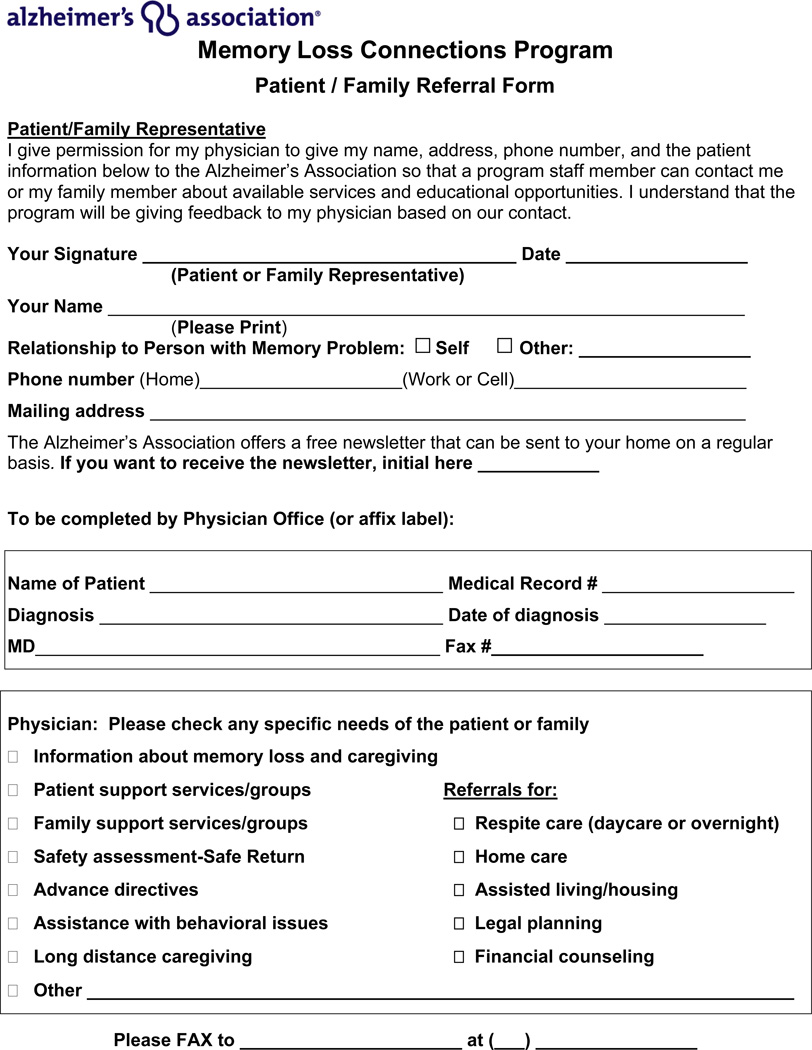

Second, primary care physicians need to be proactive in making referrals to Alzheimer’s Association chapters. Some patients feel stigmatized by a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease or other dementia and may be reluctant to receive services that may be helpful, even in early stages of the disorder. However, it is unlikely that the types of services provided by the Alzheimer’s Association will be integrated within medical practices and linkages to community-based services are essential. Currently, physician referral of patients is haphazard and uncommon. In response, for the intervention study, we created a physician fax referral form (Figure 1). This form can be customized to suit individual practices and local Alzheimer’s Association chapters. For example, it could be integrated into electronic health records and e-faxed automatically at the conclusion of the visit.

Figure 1.

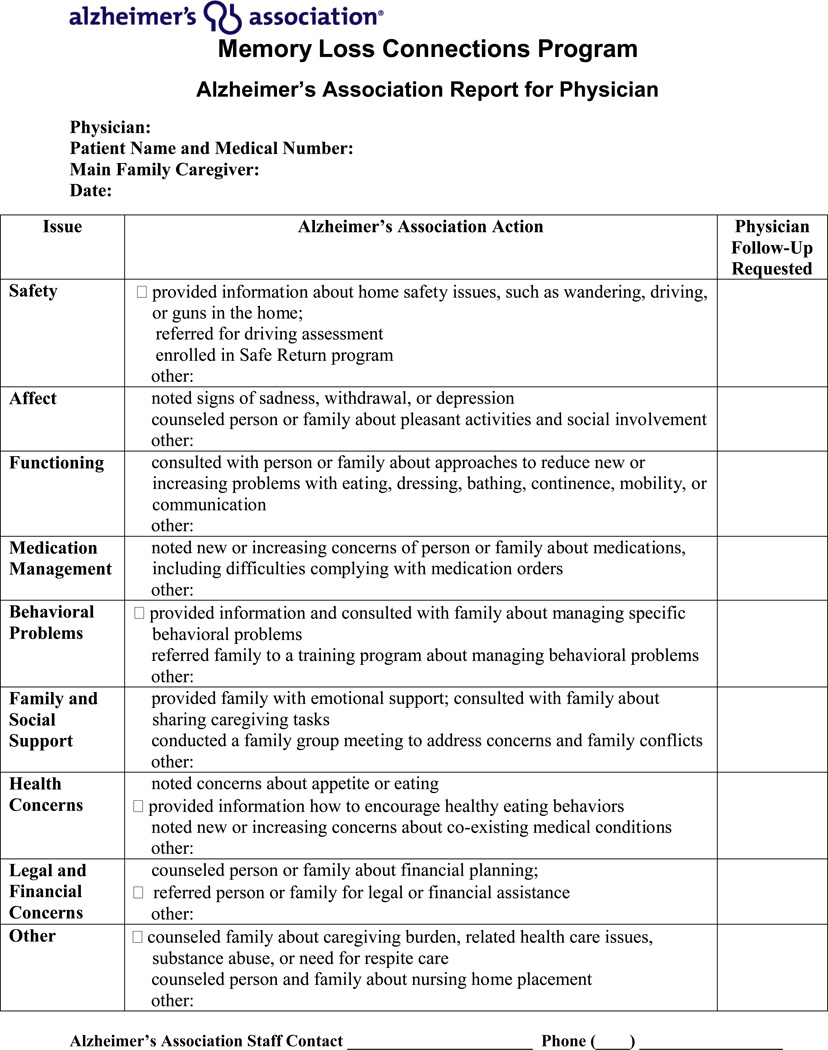

Third, primary care physicians are receptive to receiving information about their patients from Alzheimer’s Association chapters but want this delivered concisely and in written form, either by fax or e-mail. We created an Alzheimer’s Association fax response form (Figure 2) to standardize communication in a manner that physicians prefer.

Figure 2.

Fourth, Medicare and other insurers need to provide coverage for beneficial services provided by the Alzheimer's Association, including counseling. A parallel example is the widespread use of diabetes educators, whose services are covered as a means of preventing downstream costs of complications of diabetes. However, the cost savings of early intervention for Alzheimer's Disease are less clear and further research is needed to build the case. In turn, the Alzheimer’s Associations will need to build the capacity to meet the demand of increased referral. At present, some states have only 1 or 2 chapter offices with limited staff.

In summary, practice redesign coupled with payment reform and increased workforce will be needed to improve dementia care. Programs like the ACOVE-2 intervention, when coupled with strong linkages to community-based services such as local Alzheimer’s chapters, hold substantial promise. Such partnerships capitalize on the strength of the physician to evaluate and treat the medical issues and the Alzheimer’s Association to facilitate management of the social, emotional, and behavioral aspects of dementia.

References

- 1.Wenger NS, Solomon DH, Roth CP, MacLean CH, Saliba D, Kamberg CJ, et al. The quality of medical care provided to vulnerable community-dwelling older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Nov 4;139(9):740–747. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenger NS, Roth CP, Shekelle PG, Young RT, Solomon DH, Kamberg C, et al. A controlled trial of a practice-based intervention to improve primary care for falls, incontinence and dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02128.x. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damron-Rodriguez J, Frank J, Heck E, Lie D, Sragow S, Cruise P, Osterweil D. Physician Knowledge of Community-Based Care: What’s the Score? Annals of Long-Term Care. 1998 Apr;6([4]):112. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pew Health Professions Commission. Health Profession Education for the Future: Schools in Service to the Nation. San Francisco, CA: Pew Charitable Trusts; 1993–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine, Division of Health Services. Defining Primary Care: An Interim Report on the Future of Primary Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner EH. Chronic Disease Management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice. 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherry DL, Vickrey BG, Schwankovsky L, et al. Interventions To Improve Quality of Care: The Kaiser Permanente-Alzheimer’s Association Dementia Care Project. Amer J Managed Care. 2004;10(8):553–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bass DM, Clark PA, Looman WJ, et al. The Cleveland Alzheimer’s Managed Care Demonstration: Outcomes After 12 Months of Implementation. Gerontologist. 2003;43(1):73–85. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark P, Bass DM, Looman WJ, et al. Outcomes for Patients With Dementia From the Cleveland Alzheimer’s Managed Care Demonstration. Aging and Mental Health. 2004;8(1):40–51. doi: 10.1080/13607860310001613329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vickrey BJ, Mittman BS, Connor KI, et al. The Effect of a Disease Management Intervention on Quality and Outcomes of Dementia Care. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145:713–726. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maslow K, Selstad J. Chronic Care Networks for Alzheimer’s Disease: Approaches for Involving and Supporting Family Caregivers in an Innovative Model of Dementia Care. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly. 2001;2(1):33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Veterans Affairs and Benjamin Rose Institute, Partners in Dementia Care, Mark Kunik, Principal Investigator. http://www.clinicaltrial.gov/ct2/show/NCT00291161?term=NCT00291161&rank=

- 13.Reuben DB, Roth C, Kamberg C, Wenger N. Restructuring Primary Care Practices to Manage Geriatric Syndromes: the ACOVE-2 Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;Vol 51:1787–1793. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casalino LP, Devers KJ, Lake TK, Reed M, Stoddard JJ. Benefits of and barriers to large medical group practice in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163((16)):1958–1964. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.16.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, et al. Changing provider behavior: An overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Medical Care. 2001;39:2–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines?: A framework for improvement. J Amer Med Assoc. 1999;282:1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 4th. New York: The Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]