Abstract

Purpose

Angiogenesis has generated interest in oncology due to its important role in cancer growth/progression, particularly when combined with cytotoxic therapies, such as radiotherapy. Among the numerous pathways influencing vascular growth and stability, inhibition of protein kinase B(Akt) or protein kinase C(PKC) can influence tumor blood vessels within tumor microvasculature. Therefore, we wanted to determine whether PKC inhibition could sensitize lung tumors to radiation.

Methods and Materials

The combination of the selective PKCβ inhibitor Enzastaurin(ENZ, LY317615) and ionizing radiation were used in cell culture and a mouse model of lung cancer. Lung cancer cell lines and human umbilical vascular endothelial cells(HUVEC) were examined using immunoblotting, cytotoxic assays including cell proliferation and clonogenic assays as well as Matrigel endothelial tubule formation. In vivo, H460 lung cancer xenografts were examined for tumor vasculature and proliferation using immunohistochemistry(IHC).

Results

ENZ effectively radiosensitizes HUVEC within in vitro models. Furthermore, concurrent ENZ treatment of lung cancer xenografts enhanced radiation-induced destruction of tumor vasculature and proliferation by IHC. However, tumor growth delay was not enhanced with combination treatment compared to either treatment alone. Analysis of downstream effectors revealed that HUVEC and the lung cancer cell lines differed in their response to ENZ and radiation such that only HUVEC demonstrate phosphorylated S6 suppression, which is downstream of mTOR. When ENZ was combined with the mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, in H460 lung cancer cells, radiosensitization was observed.

Conclusion

PKC appears to be crucial for angiogenesis and its inhibition by ENZ has potential to enhance radiotherapy in vivo.

Keywords: Enzastaurin, PKC, radiation, lung cancer, angiogenesis

INTRODUCTION

Tumor vasculature is an attractive target for cancer treatment that has developed tremendously in recent years. Anti-angiogenic and anti-vascular therapy has generated interest in oncology due to the improvement in efficacy afforded to combination treatment with other systemic agents as well as ionizing radiation. Numerous pathways have been examined that influence vascular growth and stability. For instance, it has been shown that inhibition of receptor tyrosine kinases(RTKs) can sensitize the tumor blood vessels to radiation resulting in greater tumor growth delay and more damage to tumor microvasculature (1). Studies have also shown that a critical player in the RTK-induced radiosensitization is phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase(PI3K). PI3K is required for several growth factor mediated survival pathways in many cell types (2, 3) and exerts its effect by one of its products, phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-triphosphate(PIP3) which, in turn, activates phosphatidylinositol dependent kinases(PDKs). PDKs trigger downstream targets, most notably protein kinase B(PKB or Akt) (4). Akt, a serine/threonine protein kinase, phosphorylates GSK3β (5) which inhibits its action. Indeed, it has been shown that GSK3β activity promotes vascular endothelium survival and function following irradiation (5).

The protein kinase C (PKC) family is another potential regulator for GSK3β (6). PKC is a family of Ser/Thr kinases that are represented in all eukaryotes (7) and are classified into classical, novel, and atypical isoforms. Classical isoforms include α, β, and γ which are Ca++ dependent and DAG sensitive. Novel isoforms include δ, ε, η, θ which are DAG sensitive but Ca++ independent because their C2-related domain does not have the Ca++ regulatable residues. Atypical isoforms include ζ, ι/λ are both Ca++ and DAG insensitive. There is tissue specificity for the PKC isoforms and genetic studies show some functional redundancies.

Interest in PKC as a clinical therapeutic target has occurred in many diseases including cardiac, diabetes, and cancer. A number of pharmaceutical companies have been developing PKC targeted agents for cancer use (8). These drugs clearly effect traditional PKC substrates, but also seem to affect the PI3K/Akt pathway (9). Enzastaurin(LY317615) referred to as ENZ in this study, is a selective inhibitor of PKCβ. It blocks the ATP transfer activity of PKCβ, though at higher concentrations, particularly at doses achievable in human plasma(1-4μM in clinical trials), it blocks other PKC family members. ENZ has been investigated in a number of tumor models including multiple myeloma (10), thyroid cancer (11), colon cancer (12), non hodgkins lymphoma (13), gastric cancer (14), pancreas cancer (15), breast (16) and glioblastoma (17). However, ENZ was originally developed as an anti-angiogenic agent (18). Since tumor vasculature is relatively radiation resistant, we sought to determine whether ENZ could sensitize tumor vasculature to radiation and how that would impact lung cancer treatment.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Cell Culture and Drug Treatment

H460, A549, H661, and H157 lung carcinoma cells(American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) and maintained in RPMI medium 1640 with 10%Fetal Bovine Serum. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells(HUVEC) were purchased from Clonetics (San Diego, CA) and maintained in EBM-2 medium supplemented with single aliquot EGM-2 MV (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD). Rapamycin was purchased from Sigma and LY317615, also called Enzastaurin(ENZ) was provided by Eli Lilly, Inc.(Indianapolis, IN) and was dissolved in DMSO as a 10mmol/L stock solution at -20°C. A Mark-1137Cs irradiator(J.L. Shepherd and Associates, Glendale, CA) at a dose rate of 1.897Gy/min was used for cells.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were incubated with ENZ(2μM) for 6h followed by 0 or 3Gy. 30 minutes later, treated cells were washed with ice-cold PBS twice before harvesting with M-Per lysis buffer(Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails(Sigma, Inc. St. Louis, MO). Protein concentration was quantified using BioRad assay kit(Hercules, CA). 25μg of total protein/well was loaded onto 8%SDS-PAGE gel and separated. Protein was transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane(Millipore, Billerica, MA) and blocked for 1h using 5%milk/1%BSA/1xTBST. Blots were incubated with anti-phosphorylated and total GSK3β, anti-phosphorylated and total S6 protein, and anti-phosphorylated-pan-PKC(Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), or anti-Actin(Sigma, Inc. St. Louis, MO) antibodies overnight at 4°C. Goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies(Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were incubated for 1h at room temperature followed by 1xTBST washes thrice. Immunoblots were developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system(PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer's protocol and autoradiography.

Cell proliferation assay

H460, H661, H157, and A549 lung cancer cells and passage 3-5 HUVEC were grown to ~70% confluency, suspended and subcultured at 5000cells/well of a 96-well plate. The following day, cells were treated with ENZ at various concentrations. Three days later, 10μl of WST-1 reagent(Rapid Cell Proliferation Kit, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was added to each well and plates were incubated for 1h. Following incubation, absorbance at 460nm was analyzed with a microplate reader. The mean and standard error were calculated for each treatment condition.

In vitro clonogenic assay

H460, H661, H157, and A549 human lung carcinoma cells and HUVEC were trypsinized and serially diluted to defined concentrations and plated in triplicate. The following day, cells were treated with DMSO control, 2μM ENZ, 25 nM rapamycin, or both, 6h prior to receiving 0-6Gy. Cells were incubated for 2h and then medium was changed. One week later, cells were fixed with 70% ethanol and stained with 1% methylene blue. Colonies were counted and surviving fraction(S.F.) was calculated by the equation(number of colonies formed/number of cells plated)/(number of colonies for sham irradiated group/number of cells plated). Dose enhancement ratios were calculated by dividing the dose(Gy) for radiation alone by the dose for radiation plus treatment(normalized for plating efficiency of treatment) for which a SF=0.2 is achieved. These results were then plotted in a semi-logarithmic format using Microsoft Excel software.

Matrigel Tubule Formation Assay

300μl Matrigel(BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was placed in each well of a 24-well tissue culture dish and allowed to polymerize at 37°C. Passage 3-6 HUVECs were treated with 1-5μM ENZ or DMSO for 6h followed by radiation at 0 or 6Gy. Thirty minutes later, HUVECs were washed with PBS, suspended with trypsin and adjusted to a density of 4.8×104cells/ml. 1ml of HUVEC cell suspension was added to each Matrigel-coated well. Once tubules were formed in control plates(~6h), the media were gently aspirated and cells were fixed and stained. Digital photographs were taken of each well. The tubules were outlined by an observer unaware of the treatment conditions, the total number of tubules for each treatment condition was determined, and the mean and standard error were calculated.

Tumor volume assessment

H460 cells were implanted as xenografts in athymic nude mice(nu/nu, 5-6 weeks old[Harlan Sprague Dawley Inc., Indianapolis, IN]). A suspension of ~2×106 cells in 50μL volume was injected subcutaneously into the left hind-limb of mice using a 1-cc syringe with 27½-gauge needle. Tumors were grown for ~1 week until average tumor volume reached 0.28cm3. Treatment groups consisted of vehicle control(5%DMSO), ENZ alone(80mg/kg), vehicle plus radiation, and ENZ plus radiation. Each treatment group contained 5 mice. Vehicle control and ENZ at doses of 80mg/kg were administered by oral gavage twice daily for 2 consecutive days followed by 5 consecutive days in which drug was given twice a day prior to either sham or 2Gy. Tumors on the hind-limbs of the mice were irradiated using a superficial X-ray irradiator(Therapax, Agfa NDT, Inc., Lewis Town, PA). The non-tumor parts of the mice were shielded by lead blocks. Tumors were measured 3 times weekly in 3 perpendicular dimensions using a Vernier caliper with tumor volume calculated using the modified ellipsoid formula (lengthX widthXheight)/2. Growth delay was determined for treatment groups relative to control tumors. All animal studies were performed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees guidelines.

Histological sections, vWF and Ki67 staining

Mice were implanted with H460 and treated as described above in the tumor volume studies. After the 7 days of treatment, mice were euthanized and tumors were paraffin fixed and then processed for immunohistochemistry through the Vanderbilt University immunohistochemistry core facility. Slides from each treatment group were stained for phospho-PKC (Novus Biologics), von Willebrand Factor using anti-vWF polyclonal antibody or Ki67 staining by the core facility. Blood vessels were quantified using anti-vWF staining by randomly selecting 5 separate 400X fields and counting the number of blood vessels per field. The number of Ki67 positive cells were scored and plotted as mean and standard error in a similar fashion to blood vessel quantification. For phospho-PKC, percent staining was calculated and plotted as mean and standard error.

Statistical analysis

For statistical testing, two-sided unpaired Student's t tests were done using Statistical Analysis System version 8.2(SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for all analyses. Differences were considered statistically significant when p<0.05. For calculation of synergy, Calcusyn version 2.1 (Biosoft, Ferguson, MO) was used. This program utilizes the Chou-Talalay method for dose-effect analysis. Combination indexes (CI) were calculated using non-constant ratios of drug vs. radiation. A CI< 1.0 was considered a synergistic interaction (19).

RESULTS

Enzastaurin sensitizes HUVEC to radiation effect

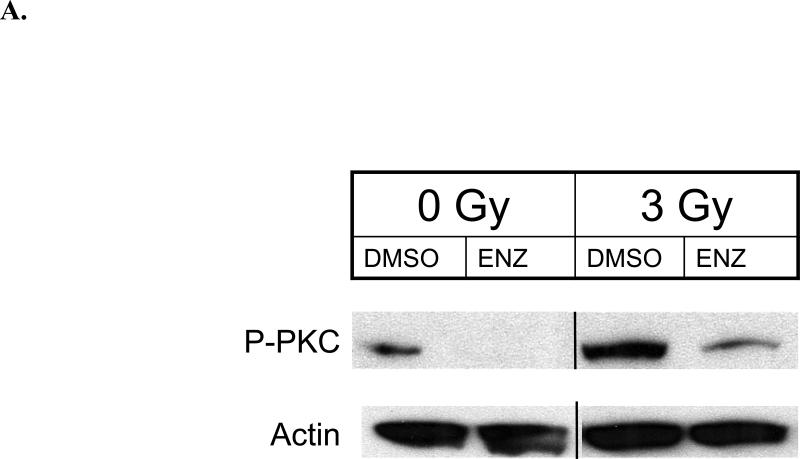

Since vascular endothelium is rather resistant to clinical doses of ionizing radiation, we studied HUVEC in terms of response to ENZ and radiation. Our initial study was to determine the effect of ENZ +/-3Gy on phosphorylation of the PKC family of proteins. As shown in Figure 1A, PKC phosphorylation, indicating activation, is induced immediately following 3Gy(0min). ENZ pretreatment effectively blocks radiation-induced PKC phosphorylation. We next examined the effect of ENZ alone on HUVEC growth by performing WST-1 cell proliferation assay as described in Methods and Materials. As shown in Figure 1B, ENZ demonstrates a clear dose response effect on endothelial cell proliferation.

Figure 1. Enzastaurin effect on HUVEC. A) PKC phosphorylation.

HUVEC were treated with 2μM ENZ for 6h followed by 0 or 3Gy with immediate harvesting followed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphorylated pan-PKC(P-PKC) and actin. B) WST-1 proliferation assay: HUVEC were subcultured and treated with indicated concentration of ENZ and incubated for 72h prior to 10μl WST-1 treatment. Mean absorbance normalized to background is displayed as % of DMSO control with standard error. C) Clonogenic survival: Passage 3-5 HUVEC were treated with 2μM ENZ for 6h followed by irradiation with 0-6Gy. Media was changed following irradiation to remove ENZ. Shown are the mean surviving fractions(S.F.) at each dose of radiation(2, 4, and 6Gy) with standard error. D) Tubule formation: Passage 3-5 HUVECs were treated with 2μM ENZ followed by 3Gy and then plated onto Matrigel-lined wells. After 6-8h, photographs were taken and tubules were quantified. Shown are representative photographs for each treatment condition and the mean and standard error.(*, p<0.001)

To determine whether ENZ can sensitize HUVEC to the cytotoxic effects of radiation, we performed clonogenic assays(Figure 1C). HUVEC were plated onto tissue culture dishes at specific densities followed by clonogenic survival assays using 2μM ENZ(6h pre-incubation). ENZ produces enhanced cytotoxic effect in HUVEC with a DER of 1.30(p <0.05).

To determine the effects of ENZ on physiological function of endothelial cells, tubule formation in Matrigel was studied with or without 2μM ENZ for 6h, followed by sham irradiation or 3 Gy and then monitored for tubule formation(Figure 1D). The use of radiation or ENZ alone had a modest effect on tubule formation. However, combined treatment reduced the number of tubules formed by over 80%(*, p<0.001).

To demonstrate synergistic interaction, the tubule formation assays were repeated using a variable dose of ENZ (0, 1, 2, and 5 μM) and a variable dose of radiation (0, 2,4, or 6 Gy). Combination indexes (CI) were then calculated for each combination using Calcusyn software based on the Chou-Talalay Method (19). CI < 1.0 is considered a synergistic interaction (highlighted in bold italics). As shown in Table 1, ENZ and radiation show synergistic interaction for tubule formation.

Table 1.

Combination index calculation for tubule formation

| Enzastaurin (μM) | Radiation (Gy) | Combination Index (CI) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0.812 |

| 1 | 4 | 0.826 |

| 1 | 6 | 0.469 |

| 2 | 2 | 0.676 |

| 2 | 4 | 0.887 |

| 2 | 6 | 0.650 |

| 5 | 2 | 0.497 |

| 5 | 4 | 1.118 |

| 5 | 6 | 0.356 |

Enzastaurin effect on lung tumor hind-limb xenografts

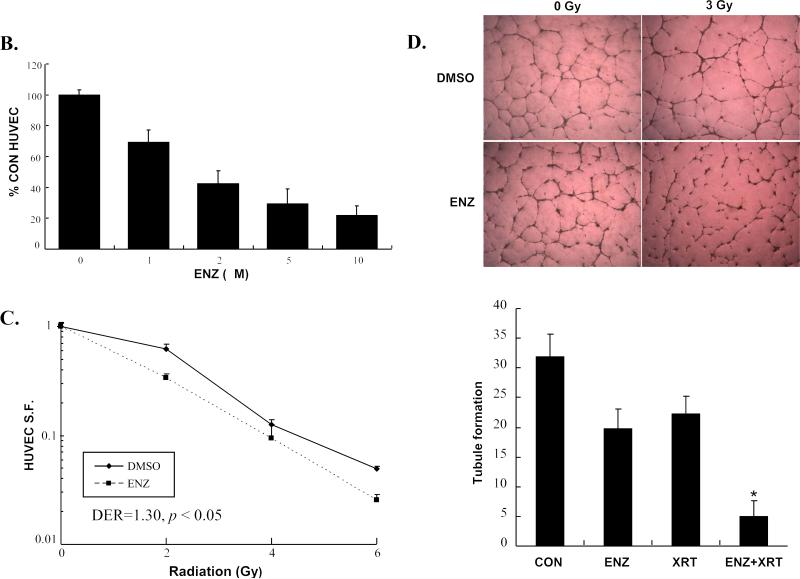

Having demonstrated that ENZ could enhance radiation in vitro based on both cytotoxic and functional assays, we wanted to determine whether ENZ enhances radiation-induced destruction of tumor vasculature in vivo. To do this, we utilized a hind-limb xenograft tumor model using H460 lung cancer cells for quantifying tumor blood vessels and proliferation within tumor sections. Animals were subjected to two consecutive days of either ENZ(80mg/kg twice daily by oral gavage) or DMSO(as vehicle control) followed by 5 consecutive days of twice daily ENZ or DMSO pretreatment prior to 2Gy or sham irradiation for a total of seven days. The tumors were then harvested and prepared for immunohistochemistry. Sections were stained for vessels(Figure 2A) and proliferation(Figure 2B) using anti-von Willebrand Factor(vWF) and anti-Ki-67, respectively. As can be seen, combination treatment was most effective at attenuating blood vessel formation(*, p<0.003 compared to Control) and proliferation(*, p<0.001 compared to either treatment alone). To confirm that ENZ was effectively blocking PKC activity, we also performed immunohistochemical analysis of phospho-PKC (Figure 2C). As can be seen, PKC phosphorylation was significantly inhibited by ENZ(*, p=0.0019 compared to control or XRT alone).

Figure 2. Enzastaurin effect on lung tumor hind-limb xenografts.

H460 hind-limb tumors were formed on athymic nude mice and treated with two consecutive twice daily treatments by oral gavage of DMSO control or 80mg/kg Enzastaurin(ENZ) followed by five consecutive daily treatments of 80mg/kg Enzastaurin(given twice daily) followed by 0 or 2Gy fractions. Tumors were harvested and stained for A) anti-vWF, B) anti-Ki-67 C) anti-phospho-PKC. Shown are microscopic photos of representative immunohistochemistry and mean level of staining with standard error.(*, p<0.003 vs. control)

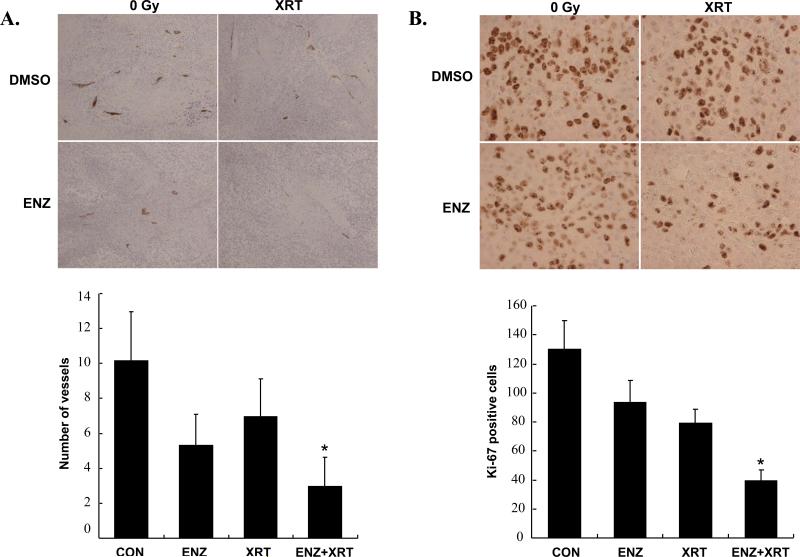

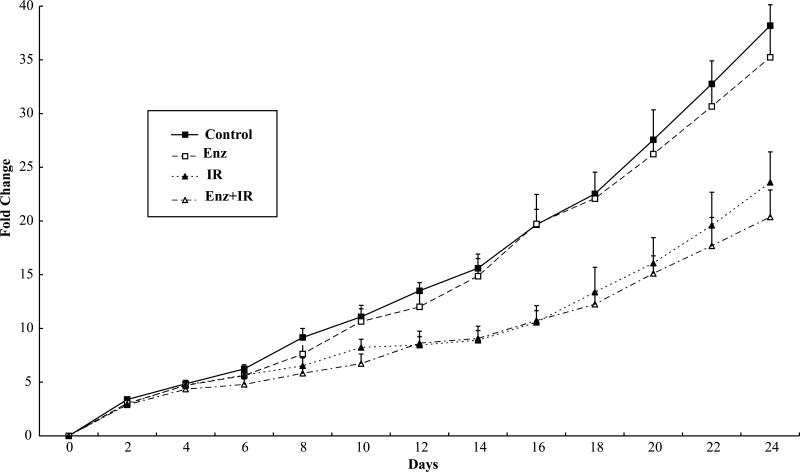

Enzastaurin does not enhance radiation tumor growth delay

To determine whether treatment with ENZ could enhance tumor growth delay in irradiated lung tumors, mice bearing H460 hind-limb tumors were treated as in Figure 2C, with oral gavage 80mg/kg ENZ or DMSO for two consecutive days followed by the same drug treatment 6h prior to 2Gy or sham irradiation for 5 consecutive days. The mean tumor volume and standard error are plotted for each treatment group in Figure 3. Whereas radiation treatment alone resulted in a tumor growth delay (p=0.0009), combination treatment demonstrated no advantage over radiation treatment alone (p=0.93).

Figure 3. Enzastaurin effect on tumor growth delay of lung cancer hind-limb xenografts.

Athymic nude mice harboring hind-limb H460 tumors were separated into 4 treatment groups: DMSO vehicle control with sham irradiation (Control), Enzastaurin with sham irradiation (Enz), radiation alone (IR), or combined Enzastaurin with radiation (Enz+IR). Treatments were given as twice daily oral gavage of 80mg/kg Enzastaurin for two consecutive days followed by the same dose of Enzastaurin given twice daily followed by sham or 2Gy which was given daily for 5 consecutive days. Tumor size was measured and volume was calculated as well as mean fold change in tumor volume and standard error for each group was plotted.

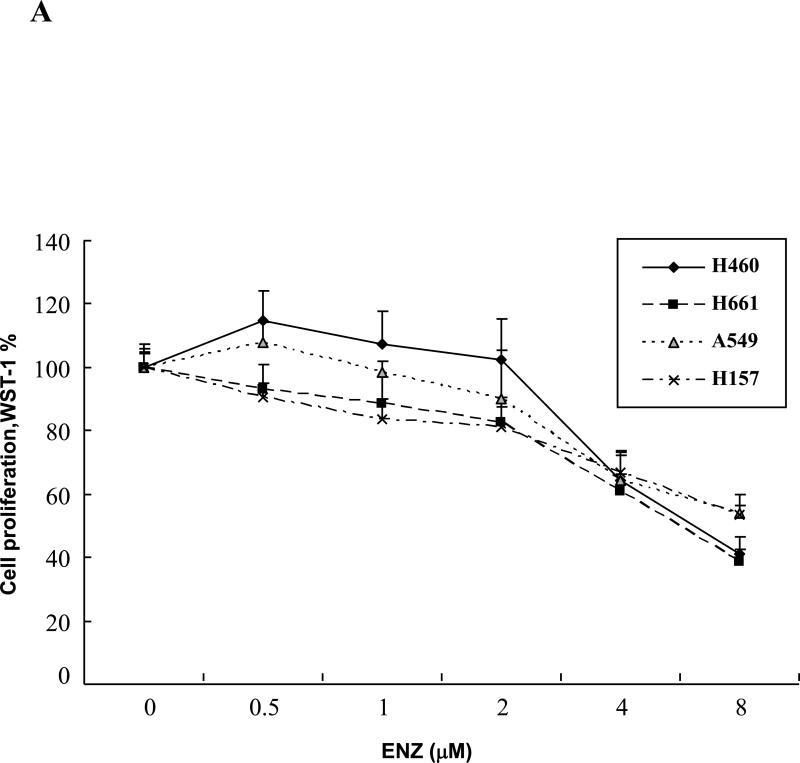

Enzastaurin inhibits cell proliferation of lung cancer cell lines

Because we could not detect any added benefit in the tumor growth delay studies by adding ENZ despite the clear anti-vascular effects in vitro and in tumor sections, we wanted to examine lung tumor cell lines directly. To do this, we first examined three human lung cancer cell lines, H460, H661, H157, and A549, for cell proliferation in vitro in response to ENZ. These lung cancer cell lines were subcultured in 96-well tissue culture plates at specific cell numbers and were then treated with 0-8μM of ENZ. 72h later, cells were stained with WST-1 reagent and absorbance was analyzed by a fluorescent microplate reader. Figure 4A shows the effect of various concentrations of ENZ on tumor cell proliferation. Compared to the results in HUVEC(Figure 1B), all of these cell lines showed significantly more resistance to ENZ such that a 50% reduction required a dose of 8μM ENZ.

Figure 4. Enzastaurin effect on lung cancer cell lines.

A) H460, H661, H157, and A549 lung cancer cell lines were cultured in 96-well plates and were treated with DMSO control or Enzastaurin(ENZ) at the specified concentrations and incubated for 72h. Following incubation, cells were treated with 10μl WST-1 reagent for cell proliferation assay. Absorbance(450nm) was measured and normalized for background and displayed as % of DMSO control with standard error. B) H460, H661, and A549 lung cancer cell lines were plated onto tissue culture dishes. After attachment, cells were treated with 2μM ENZ for 6h followed by irradiation with 0-6Gy. Media was changed following irradiation to remove ENZ. Shown are the mean surviving fractions(S.F.) at each dose of radiation(2, 4, and 6Gy) with standard error.

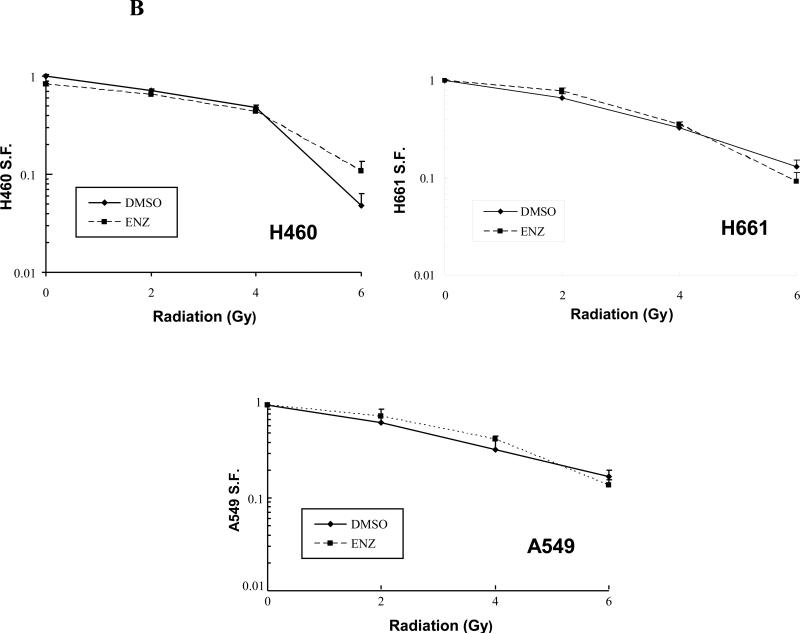

Enzastaurin does not radiosensitize lung cancer cell lines

Despite the lack of anti-proliferative effect by ENZ alone, we wanted to determine whether ENZ could provide any sensitization to the cytotoxic effects of ionizing radiation in the lung cancer cell lines. Therefore, H460, H661, and A549 cells were plated onto tissue culture dishes at specific densities followed by clonogenic survival assays as in Figure 1C and as described in Materials and Methods. Figure 4B shows the mean SF and standard error(n=3) for each treatment condition. As seen with the WST-1 assay, use of ENZ for 6h prior to irradiation did not produce a significant shift (p>0.5, non-significant, NS) in the survival curves indicating that, at least in the cell lines examined, ENZ did not show a radiosensitizing effect, unlike what was seen in HUVEC(Figure 1C).

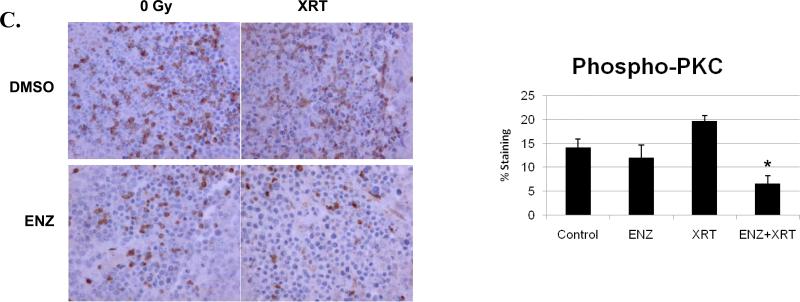

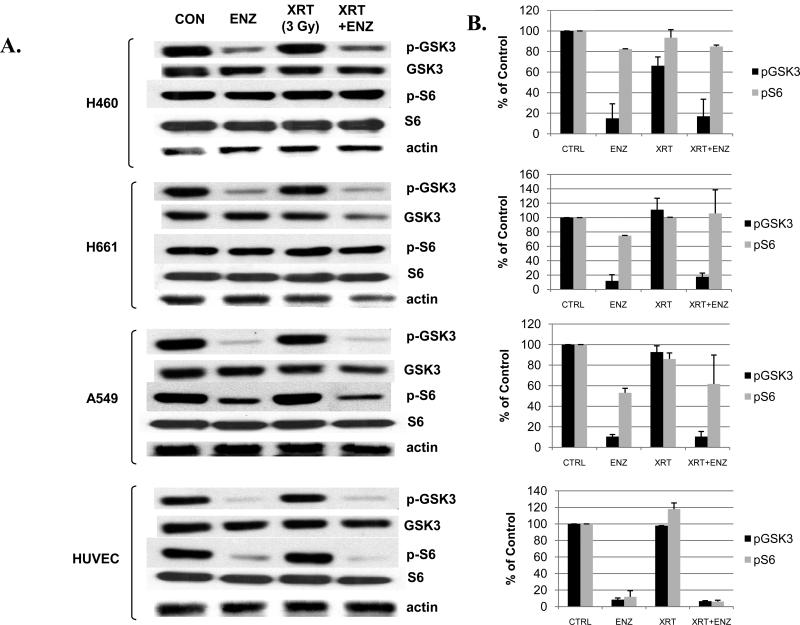

Enzastaurin has differential effect on signaling proteins in cell lines

To explore potential reasons why ENZ was ineffective in tumor growth delay model of lung cancer, we studied the lung cancer cell lines, H460, H661, and A549 as well as HUVEC to determine if a differential effect could be observed in signal transduction pathways. Previous studies in other cell types using ENZ demonstrate that attenuation of certain downstream signaling proteins correlates with response, particularly the Akt pathway. Therefore, Figure 5 illustrates two potential downstream effectors that could possibly influence drug and/or radiation response. These cell lines were treated with DMSO control(Con) or 2μM ENZ for 6h prior to sham or 3Gy and then harvested 30min later for Western blot analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Phosphorylated GSK3β(p-GSK3) is a downstream target of Akt that correlates with growth and phosphorylated S6(p-S6) protein is a ribosomal protein important for protein synthesis and cell growth. In all cell lines tested, p-GSK3 was effectively attenuated by ENZ. However, p-S6 was significantly blocked by ENZ only in HUVEC suggesting that an S6-dependent mechanism influences response to ENZ treatment. ENZ treatment had no effect on levels of any of these proteins.

Figure 5. Western blot analysis of Enzastaurin effect on cell lines.

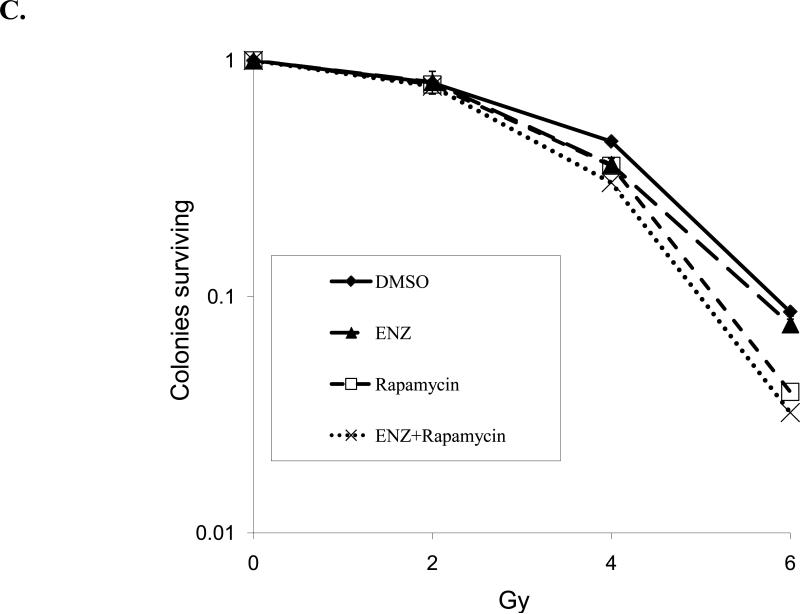

H460, H661, and A549 lung cancer cell lines and HUVECs were serum starved and treated for 6h with 2μM Enzastaurin(ENZ) or DMSO vehicle control(Con) prior to irradiation with 3Gy. Protein was extracted 30min after irradiation. A) Immunoblot analysis is shown using antibodies to phosphorylated GSK3β(p-GSK3), total GSK3β(GSK3), phosphorylated S6(p-S6), total S6(S6) and actin. B) Densitometry was performed for p-GSK3 and p-S6 normalized to actin and displayed as mean % of control with standard error (SEM). C) Clonogenic survival assay was performed on H460 cells with 2μM ENZ +/- rapamycin (25 nM).

Since the S6 protein is downstream of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), we sought to evaluate the effect of mTOR inhibition in combination with ENZ in terms of radiosensitivity. Therefore, we repeated clonogenic assays for H460 lung cancer cells as in Figure 4B with the addition of 25 nM rapamycin. As shown in Figure 5C, rapamycin treatment yielded enhanced radiation cytotoxicity (p=0.0042, control v. rapamycin), which was maintained when combined with ENZ though rapamycin effect predominated (p=NS, rapamycin v. ENZ + rapamycin).

DISCUSSION

The PKC family of serine/threonine kinases has been actively targeted for drug development in recent years. Unfortunately, clinical data has been rather disappointing with several lead compounds discarded due to lack of efficacy. Nevertheless, interest in PKC modulators remains based on a multitude of preclinical evidence implicating PKC in tumorigenesis and response to therapy. The main issue that seems to be complicating this field is that PKC isozymes and isoforms can have antagonistic effects, even within the same subfamily. For instance, PKCβ has two splice variants, PKCβI and PKCβII. Interestingly, these two proteins appear to have opposing effects on tumor growth. PKCβI is found to be downregulated in colon cancer and when expressed tends to predict for a less aggressive tumor (20). However, PKCβII expression enhances carcinogenesis and occurs rather early in the process (21).

ENZ has been tested in phase I studies and has been demonstrated to be a safe, orally bio-available drug (22). The most promising published trials to date have been in refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma patients which has shown improved failure free survival and some complete responses (13). However, a cooperative group Phase II study in advanced lung cancer patients showed only 13% of patients treated with ENZ had progression free survival≥6 months (23). Our study indicates that ENZ, at least at 2μM, did not affect proliferation(Figure 4) and did not enhance tumor control(Figure 3) in human lung cancer cell lines. Furthermore, Hanauske et al. showed limited growth inhibition at 1.4μM in both lung cancer cell lines and freshly explanted tumor cells, even with prolonged incubation(21 days) (24). Since ENZ has failed to show clear objective response in most solid tumors as a single agent (22), investigations using combinations of ENZ with other cytotoxic agents(including ionizing radiation) have shown more promise (11, 17). However, in some cases, very large doses of ENZ(up to 15μM) and/or large radiation doses(15-25Gy) are required to see benefit (16, 25). Interestingly, sequencing of ENZ with those agents may be critical, particularly in lung cancer models, as antagonistic effects can occur (26). The fact that we saw no tumor growth delay(Figure 3) despite seeing changes in vascular response(Figures 1 and 2) suggests a possible differentiation between in vitro and in vivo studies. Therefore, additional pre-clinical studies may help determine better ways of utilizing ENZ.

Interestingly, ENZ has been studied in several cancer cell models and appears to be most effective when the PI3K-Akt-GSK3β pathway is also blocked by the drug. This GSK3β pathway disruption has been demonstrated in cell lines as diverse as colon carcinoma and glioblastoma (12). As such, groups have tried to identify potential biomarkers for ENZ response. Some have advocated the examination of peripheral blood mononuclear cells for attenuation of phosphorylated PKC (27) while others have examined inhibition of more downstream effectors such as GSK3β phosphorylation (12). However, our studies presented here suggest that simply determining the effect of ENZ on GSK3β phosphorylation would be insufficient to predict for radiosensitization since all of the lung cancer cell lines and HUVEC showed inhibition of GSK3β phosphorylation, yet only HUVEC were radiosensitized. Interestingly, a recent study using multiple myeloma models have suggested that cell survival may be independent of GSK3β (10). It should be noted, however, that other groups have utilized both GSK3β phosphorylation and S6 protein phosphorylation as surrogates for ENZ activity (11). Indeed, the fact that only HUVEC showed attenuation of both GSK3β and S6 phosphorylation as well as radiosensitization suggests that perhaps S6 is a better surrogate, at least when it comes to radiation sensitivity.

It is important to note that ENZ was originally developed as an anti-angiogenic agent. However, it is unclear whether ENZ exerts this effect based on PKCβ inhibition or other PKC isoform inhibition. Since ENZ shows its selectivity in vitro at low nanomolar concentrations, the micromolar doses achieved clinically and used for virtually all of the published studies on ENZ do not rule out the possibility that ENZ is attenuating other PKC family members to exert its effect. Indeed, our Western blot data showed pan-PKC inhibition(Figure 1A) and a recent study examining radiation with ENZ in MCF-7 breast cancers showed effective inhibition of PKCα and ε (16). In summary, we show in the present study that ENZ sensitizes vascular endothelium to radiation both in vitro and in vivo. Combination treatment with ENZ and radiation inhibited tumor proliferation and angiogenesis but failed to enhance tumor growth delay in an H460 xenograft model. Observed differences in sensitivity appear to be related to S6 phosphorylation status.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported in part by NCRR instrument grant 1S10 RR17858 and Lilly Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No conflicts of interest to report

REFERENCES

- 1.Geng L, Donnelly E, McMahon G, et al. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor signaling leads to reversal of tumor resistance to radiotherapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2413–2419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fantl WJ, Johnson DE, Williams LT. Signalling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:453–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2905–2927. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholson KM, Anderson NG. The protein kinase B/Akt signalling pathway in human malignancy. Cell Signal. 2002;14:381–395. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan J, Geng L, Yazlovitskaya EM, et al. Protein kinase B/Akt-dependent phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in irradiated vascular endothelium. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2320–2327. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meijer L, Flajolet M, Greengard P. Pharmacological inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase 3. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2004;25:471–480. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker PJ, Murray-Rust J. PKC at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:131–132. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackay HJ, Twelves CJ. Targeting the protein kinase C family: are we there yet? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:554–562. doi: 10.1038/nrc2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riesterer O, Tenzer A, Zingg D, et al. Novel radiosensitizers for locally advanced epithelial tumors: inhibition of the PI3K/Akt survival pathway in tumor cells and in tumor-associated endothelial cells as a novel treatment strategy? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Podar K, Raab MS, Zhang J, et al. Targeting PKC in multiple myeloma: in vitro and in vivo effects of the novel, orally available small-molecule inhibitor enzastaurin (LY317615.HCl). Blood. 2007;109:1669–1677. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-042747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oberschmidt O, Eismann U, Schulz L, et al. Enzastaurin and pemetrexed exert synergistic antitumor activity in thyroid cancer cell lines in vitro. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;43:603–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graff JR, McNulty AM, Hanna KR, et al. The protein kinase Cbeta-selective inhibitor, Enzastaurin (LY317615.HCl), suppresses signaling through the AKT pathway, induces apoptosis, and suppresses growth of human colon cancer and glioblastoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7462–7469. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson MJ, Kahl BS, Vose JM, et al. Phase II study of enzastaurin, a protein kinase C beta inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1741–1746. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KW, Kim SG, Kim HP, et al. Enzastaurin, a protein kinase C beta inhibitor, suppresses signaling through the ribosomal S6 kinase and bad pathways and induces apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1916–1926. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spalding AC, Watson R, Davis ME, et al. Inhibition of protein kinase Cbeta by enzastaurin enhances radiation cytotoxicity in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6827–6833. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jasinski P, Terai K, Zwolak P, et al. Enzastaurin renders MCF-7 breast cancer cells sensitive to radiation through reversal of radiation-induced activation of protein kinase C. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1315–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabatabai G, Frank B, Wick A, et al. Synergistic antiglioma activity of radiotherapy and enzastaurin. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:153–161. doi: 10.1002/ana.21057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keyes K, Cox K, Treadway P, et al. An in vitro tumor model: analysis of angiogenic factor expression after chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5597–5602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:621–681. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein DR, Cacace AM, Weinstein IB. Overexpression of protein kinase C beta 1 in the SW480 colon cancer cell line causes growth suppression. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:1121–1126. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.5.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gokmen-Polar Y, Murray NR, Velasco MA, et al. Elevated protein kinase C betaII is an early promotive event in colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1375–1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carducci MA, Musib L, Kies MS, et al. Phase I dose escalation and pharmacokinetic study of enzastaurin, an oral protein kinase C beta inhibitor, in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4092–4099. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh Y, Herbst RS, Burris H, et al. Enzastaurin, an oral serine/threonine kinase inhibitor, as second- or third-line therapy of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1135–1141. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanauske AR, Oberschmidt O, Hanauske-Abel H, et al. Antitumor activity of enzastaurin (LY317615.HCl) against human cancer cell lines and freshly explanted tumors investigated in in-vitro [corrected] soft-agar cloning experiments. Invest New Drugs. 2007;25:205–210. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dudek AZ, Zwolak P, Jasinski P, et al. Protein kinase C-beta inhibitor enzastaurin (LY317615.HCI) enhances radiation control of murine breast cancer in an orthotopic model of bone metastasis. Invest New Drugs. 2008;26:13–24. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9079-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgillo F, Martinelli E, Troiani T, et al. Sequence-dependent, synergistic antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects of the combination of cytotoxic drugs and enzastaurin, a protein kinase Cbeta inhibitor, in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1698–1707. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green LJ, Marder P, Ray C, et al. Development and validation of a drug activity biomarker that shows target inhibition in cancer patients receiving enzastaurin, a novel protein kinase C-beta inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3408–3415. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]