Abstract

Molecular intervention using noninvasive myocardial gene transfer holds great promise for treating heart diseases. Robust cardiac transduction from peripheral vein injection has been achieved in rodents using adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype-9 (AAV-9). However, a similar approach has failed to transduce the heart in dogs, a commonly used large animal model for heart diseases. To develop an effective noninvasive method to deliver exogenous genes to the dog heart, we employed an AAV-8 vector that expresses human placental alkaline phosphatase reporter gene under the transcriptional regulation of the Rous sarcoma virus promoter. Vectors were delivered to three neonatal dogs at the doses of 1.35×1014, 7.14×1014, and 9.06×1014 viral genome particles/kg body weight via the jugular vein. Transduction efficiency and overall safety were evaluated at 1.5, 2.5, and 12 months postinjection. AAV delivery was well tolerated and dog growth was normal. Blood chemistry and internal organ histology were unremarkable. Widespread skeletal muscle transduction was observed in all dogs without T-cell infiltration. Encouragingly, whole heart myocardial transduction was achieved in two dogs that received higher doses and cardiac expression lasted for at least 1 year. In summary, peripheral vein AAV-8 injection may represent a simple heart gene transfer method in large mammals. Further optimization of this gene delivery strategy may open the door for a readily applicable gene therapy method to treat many heart diseases.

Pan and colleagues administer, via the jugular vein, adeno-associated virus serotype 8 (AAV8) vector expressing a human placental alkaline phosphatase reporter gene under the control of the Rous sarcoma virus promoter to three neonatal dogs at doses of 1.35 × 1014, 7.14 × 1014, and 9.06 × 1014 viral genome particles/kg body weight. Using this approach, they observe widespread skeletal muscle transduction in all dogs without T cell infiltration. Interestingly, whole heart myocardial transduction was achieved in the two dogs that received the highest doses, and this expression lasted for at least 1 year.

Introduction

Heart diseases are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, 17.3 million people died from cardiovascular disease in 2008, and this number will go up to ∼23.3 million by 2030 (www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/en/). In light of this global trend, there is an increased demand for novel therapeutic modalities to treat heart diseases. Since genetic factors play essential roles in the health and disease of the heart, there is a huge potential to intervene heart disease using therapeutic gene transfer (Duan, 2011b; Wasala et al., 2011).

Over the last several decades, tremendous progress has been made in delivering therapeutic genes to the heart (Kratlian and Hajjar, 2012; Wasala et al., 2011). A number of complicated techniques have been developed to transduce the myocardium by direct injection (to the myocardium or ventricular cavity), pericardial injection, coronary perfusion, and aorta injection using a variety of viral and nonviral vectors (Ishikawa et al., 2011; Katz et al., 2011; Wasala et al., 2011). Some of these invasive cardiac gene delivery methods, such as percutaneous intracoronorary delivery, have begun to show promise in treating heart failure in human patients (Jaski et al., 2009; Jessup et al., 2011). While these achievements are encouraging, sophisticated procedures and risks associated with heart surgery remain important limitations for wide application of these novel therapeutic interventions in general practice. Methods that allow effective cardiac transduction from a peripheral vein will greatly minimize potential complications associated with invasive heart gene delivery.

Systemic gene transfer was first reported by Chamberlain and colleagues using adeno-associated virus serotype-6 (AAV-6; Gregorevic et al., 2004). The authors observed widespread myocardial transduction following a single tail vein injection in mice (Gregorevic et al., 2004). Subsequent studies from several other groups suggest that robust whole heart transduction can also be achieved with AAV-8 and AAV-9 via intra-arterial or intravenous injection in rodents (Bostick et al., 2007; Pacak et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2005). Of three reported AAV serotypes, AAV-9 is especially recommended for heart gene transfer because it is much more potent and selective to the heart than AAV-6 and AAV-8 (reviewed in Wasala et al., 2011). Surprisingly, when we tested the so claimed “cardiotropic” AAV-9 in newborn dogs, barely any cardiomyocytes were transduced despite robust bodywide skeletal muscle transduction (Yue et al., 2008). This unexpected finding casts doubts on the future application of AAV-9 in large mammals.

To overcome this hurdle, here we explored systemic AAV-8 gene delivery in neonatal puppies. Three different vector doses were tested. Low dose injection (1.35×1014 viral genome [vg] particles/kg body weight) resulted in sporadic myocardial transduction. However, a 5-fold increase in the dosage dramatically changed the outcome. Striking transduction was obtained in the atria, ventricles, septa, and papillary muscles for at least 12 months in two dogs that received either 7.14×1014 or 9.06×1014 vg particles/kg body weight of AAV-8. Our results suggest that AAV-8–based peripheral vein injection may represent a promising way to transduce the heart in large mammals.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri and were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guideline. Three dogs were used in the study including two normal males (Zeus and Charmander) and one female carrier dog (Artemis) that had a mutated dystrophin gene in one of its X chromosomes (Table 1). All experimental dogs were generated by artificial insemination at the University of Missouri, and they were on a mixed genetic background of golden retriever, Labrador retriever, beagle, and Welsh corgi. The genotyping was determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as we described before (Fine et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2011).

Table 1.

Injection Summary

| |

Dog name |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeus | Artemis | Charmander | |

| Sex | Male | Female | Male |

| Age at the time of injection (day) | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| BW at the time of injection (g) | 540 | 412 | 420 |

| Injection volume (mL/kg BW) | 7.29 | 14.56 | 14.29 |

| AAV dosage (vg particle/kg BW) | 1.35×1014 | 9.06×1014 | 7.14×1014 |

| Age at necropsy (month) | 1.5 | 2.5 | 12 |

BW, body weight; vg, viral genome; AAV, adeno-associated virus.

Recombinant AAV-8 vector

The proviral cis plasmid has been published before (Yue et al., 2008). In this vector, the heat-resistant human placental alkaline phosphatase (AP) reporter gene was expressed under the transcriptional control of the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) promoter and the simian virus 40 (SV40) polyadenylation signal. Recombinant AAV-8 stock was generated using a triple plasmid transfection method as we described before (Shin et al., 2012a). The AAV-8 Rep-Cap helper plasmid was a generous gift of Dr. James Wilson (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). The adenoviral helper plasmid pHelper was obtained from Agilent Technologies (Clara, CA). Recombinant viral stocks were purified through three rounds of isopycnic CsCl ultracentrifugation followed by three changes of HEPES buffer at 4°C for 48 hr. Endotoxin contamination was examined using the limulus amebocyte lysate assay using the Endosafe limulus amebocyte lysate gel clot test kit (Charles Rivers Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). The endotoxin levels in our viral stocks were within the acceptable level recommended by the Food and Drug Administration. Viral titer was determined by quantitative PCR using a forward primer (5′-GGTTGTACGCGGTTAGGAGT-3′) and a reverse primer (5′-GGCATGTTGCTAACTCATCG-3′) that amplified a fragment in the RSV promoter.

Gene delivery and dog necropsy

Systemic AAV-8 delivery was performed in conscious newborn puppies by a single bolus injection through the jugular vein (Table 1). At 1.5, 2.5, and 12 months postinjection, the dogs were euthanized and necropsies were performed. Major muscles from the head (temporalis, tongue), neck (sternocephalicus), shoulder (deltoid), thorax (superficial pectoralis), abdomen (abdominal rectus), forelimb (extensor carpi ulnaris, extensor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor carpi radialis, biceps brachii, triceps brachii lateral head and long head), and hind limb (cranial tibialis, extensor digitorum longus, gastrocnemius, cranial sartorius, rectus femoris, and biceps femoris) as well as the diaphragm (sternal, costal, and lumbar part), heart (right and left atria, right and left ventricles, papillary muscles, and interventricular septum), and other internal organs (liver, pancreas, spleen, lung, and kidney) were harvested. Two pieces of samples were collected from each tissue. One piece was frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) media for cryosection and histological examinations. The other piece was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for genomic DNA and protein extraction.

Blood chemistry

Blood was drawn from two of the experimental subjects (Artemis and Charmander) before euthanasia. For Zeus, the blood was collected after the dog was euthanized. Laboratory biochemical tests were performed at the UMC Vet Med Diagnostic Lab (Columbia, MO).

Histological examination of AP reporter gene expression

AP histochemical staining was carried out on 8-μm-thick cryosections as we described before (Shin et al., 2012c; Yue et al., 2008, 2011). Briefly, tissue sections were fixed in 0.5% glutaraldehyde for 10 min. After washing with 1 mM MgCl2, slides were incubated at 65°C for 45 min to inactivate endogenous AP activity. Slides were subsequently washed in a prestaining buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.5, 50 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl. Finally slides were stained in the freshly prepared AP staining solution (165 mg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate-p-toluidine, 330 mg/mL nitroblue tetrazolium chloride, 50 mM levamisole) for 5 to 20 min. Cryosections from an uninfected dog (Frank) were used as negative controls for AP staining (Yue et al., 2008).

Examination of AP activity assay in tissue lysate

Total protein lysate was extracted as we described before (Yue et al., 2011). Protein concentration was determined using the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). AP activity was measured by a colorimetric method using the Stem TAGTM alkaline phosphatase activity assay kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA). Prior to the assay, endogenous AP activity was inactivated by incubating the lysate at 65°C for 1 hr.

Vector genome copy number determination

Genomic DNA was extracted from freshly frozen tissue samples. The AAV genome copy was determined using the Fast SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) by quantitative PCR (qPCR) in an ABI 7900 HT qPCR machine. The same set of the primers that were used for AAV titer determination was used for quantifying AAV genome copy in tissues.

Results

A single intravenous injection of AAV-8 efficiently transduces whole-body skeletal muscle in neonatal dogs

We have previously demonstrated bodywide skeletal muscle gene transfer in neonatal puppies using AAV-9 (Yue et al., 2008, 2011). Since AAV tissue tropism is partially determined by the viral capsid, we decided to test AAV-8, another AAV serotype that has been used for systemic gene transfer in rodents (Wang et al., 2005). AAV-8 was injected as a single bolus through the jugular vein to three newborn puppies and AAV transduction efficiency was examined at different time points after injection (Table 1). Specifically, a male puppy Zeus received 1.35×1014 vg particles/kg body weight at age day 2 and was harvested at 1.5 months after injection. A female puppy Artemis was injected with 9.06×1014 vg particles/kg body weight at age day 2 and was harvested at the age of 2.5 months. Another male puppy Charmander was administered with 7.14×1014 vg particles/kg body weight at age day 5 and transduction efficiency was evaluated when the dog was 1-year-old.

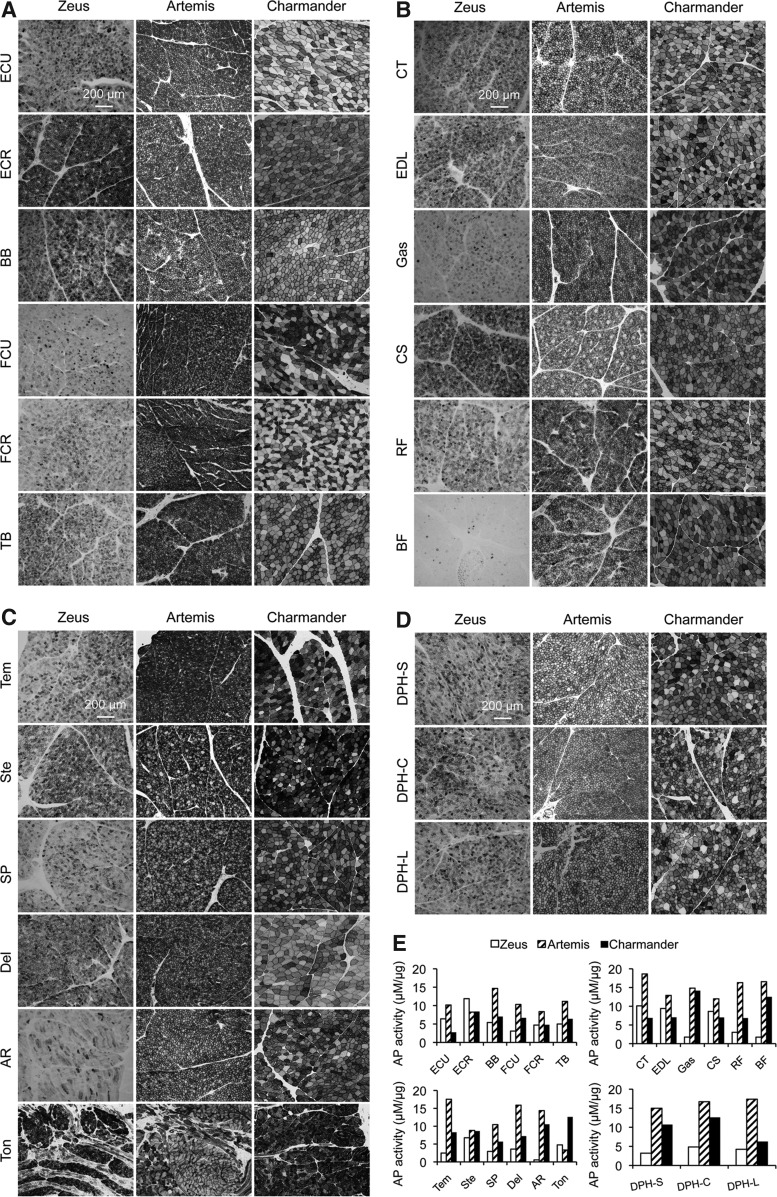

Skeletal muscles from major body areas (including the head, shoulder, chest, abdomen, forelimb, hind limb, and the diaphragm and tongue) were examined for AP expression by histochemical staining and enzymatic activity assay in lysate (Fig. 1). Widespread AP expression was detected in all muscles examined. As expected, a higher dose yielded stronger transduction. In Artemis, the dog that received the highest dose, homogenous expression was seen in essentially every myofiber in every muscle (Fig. 1). A slight reduction in dose (Charmander) still yielded nearly saturated expression in every muscle (Fig. 1). However, a more heterogeneous expression pattern was observed in Zeus, the dog that received the lowest dose. While some of Zeus's muscles showed transduction efficiency comparable to that of the corresponding muscles in Artemis and Charmander (such as the extensor carpi radialis, biceps brachii, cranial sartorius, and tongue), other muscles (such as the gastrocnemius and biceps femoris) showed a clear trend of reduced transduction in Zeus (Figs. 1B and 1E).

FIG. 1.

Robust body-wide skeletal muscle transduction following systemic AAV-8 injection in neonatal dogs. (A) Representative photomicrographs of alkaline phosphatase (AP) histochemical staining from forelimb muscles. ECU, extensor carpi ulnaris; ECR, extensor carpi radialis; BB, biceps brachii; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; FCR, flexor carpi radialis; TB, triceps brachii. (B) Representative photomicrographs of AP histochemical staining from hind limb muscles. CT, cranial tibialis; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; Gas, gastrocnemius; CS, cranial sartorius; RF, rectus femoris; BF, biceps femoris. (C) Representative photomicrographs of AP histochemical staining from muscles in the head, neck, shoulder, chest and abdomen. Tem, temporalis; Ste, sternocephalicus; SP, superficial pectoralis; Del, deltoid; AR, abdominal rectus; Ton, tongue. (D) Representative photomicrographs of AP histochemical staining from the sternal (DPH-S), costal (DPH-C), and lumbar (DPH-L) side of the diaphragm. (E) Quantitative examination of AP activity in muscle lysate. Top left panel, forelimb muscles: ECU, extensor carpi ulnaris; ECR, extensor carpi radialis; BB, biceps brachii; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; FCR, flexor carpi radialis; TB, triceps brachii. Top right panel, hind limb muscles: CT, cranial tibialis; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; Gas, gastrocnemius; CS, cranial sartorius; RF, rectus femoris; BF, biceps femoris. Bottom left panel, head, neck, shoulder, chest and abdominal muscles: Tem, temporalis; Ste, sternocephalicus; SP, superficial pectoralis; Del, deltoid; AR, abdominal rectus; Ton, tongue. Bottom right panel, sternal (DPH-S), costal (DPH-C) and lumbar (DPH-L) side of the diaphragm.

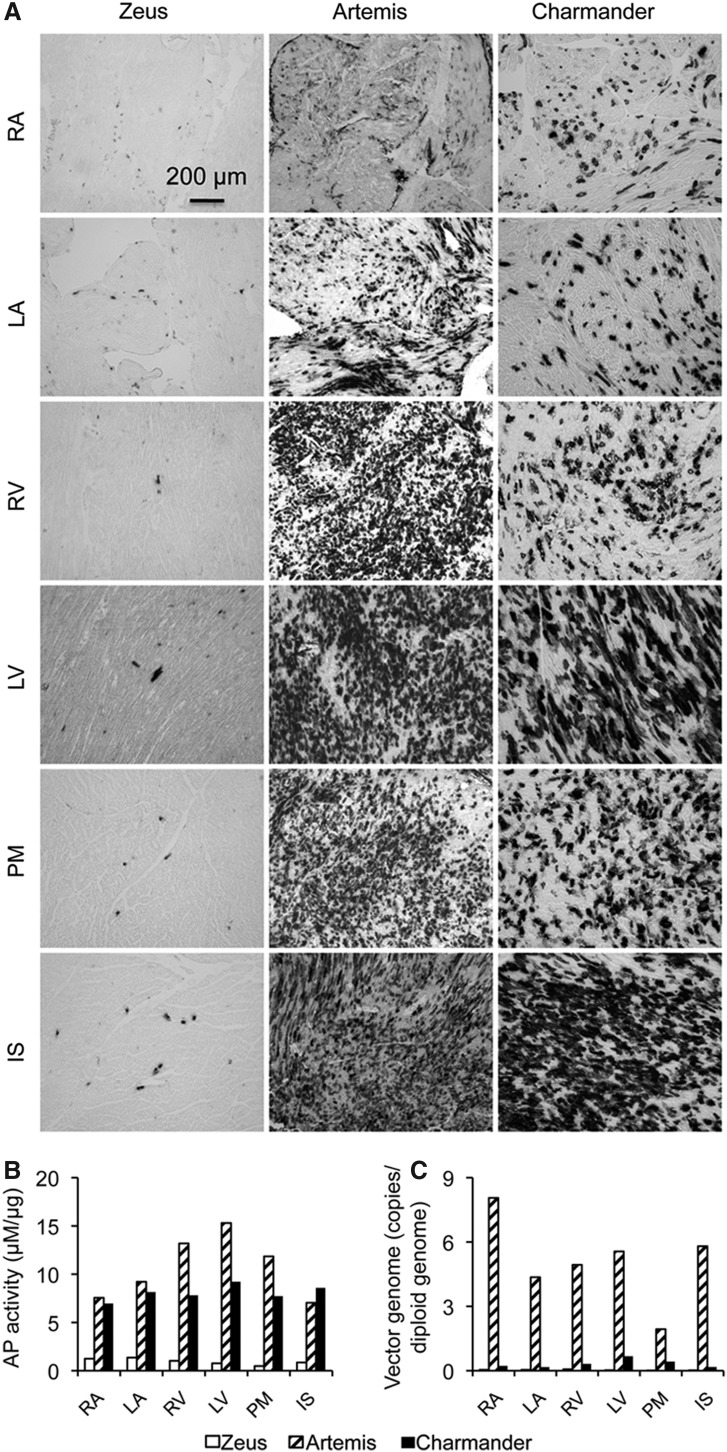

Intravascular AAV-8 injection results in a dose-dependent transduction of the dog heart

Poor myocardial transduction is a major deficiency of systemic AAV-9 gene transfer in dogs (Yue et al., 2008). To determine whether switching to AAV-8 improved cardiac transduction, we sampled every part of the heart including both atria, both ventricles, the septum, and papillary muscles (Fig. 2). There was minimal AP expression in the heart of Zeus, the dog that received lowest amount of AAV-8 (1.35×1014 vg particles/kg body weight). In Artemis (9.06×1014 vg particles/kg body weight) and Charmander (7.14×1014 vg particles/kg body weight), we detected robust gene transfer in the entire hearts (Fig. 2). Essentially, near-saturated AP expression (60% to 80%) was observed in both ventricles, the septum, and papillary muscles in the heart of Artemis (Fig. 2). The left ventricle and septum of the heart of Charmander also showed 50% to 80% transduction. The transduction efficiency appeared lower in the atria. However, it still reached approximately 10% to 40% in Artemis and Charmander (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Dose-dependent myocardial transduction following systemic AAV-8 injection in neonatal dogs. (A) Representative photomicrographs of AP histochemical staining from different parts of the heart. (B) Quantitative examination of AP activity in muscle lysate from different parts of the heart. (C) AAV genome copy quantification in different parts of the heart. RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; PM, papillary muscle; IS, interventricular septum.

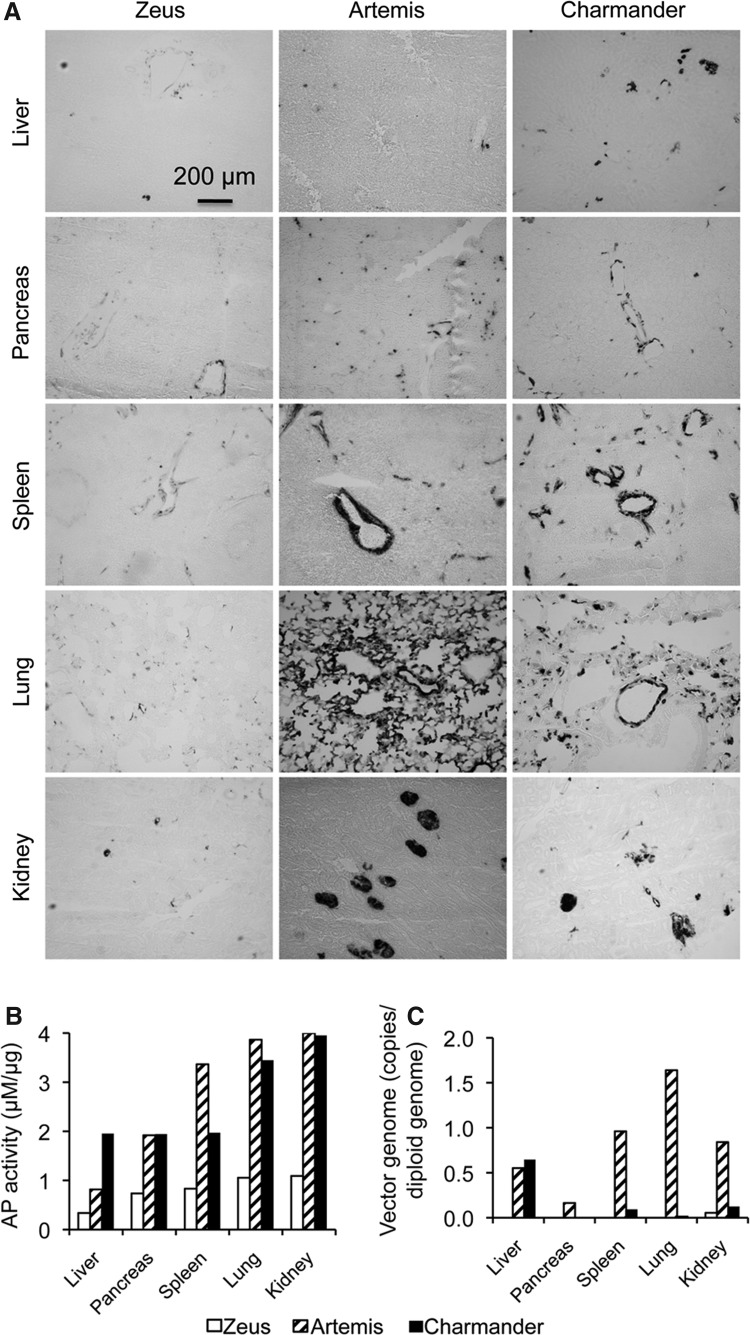

Transduction of internal organs by systemic AAV-8 injection in dogs

Next, we examined AP expression in several internal organs including the liver, pancreas, spleen, lung, and kidney (Fig. 3). We have previously shown that systemic AAV-9 injection in newborn puppies results in minimal transduction of internal organs (Yue et al., 2008). Consistently, we also observed nominal internal organ transduction with AAV-8 in Zeus (Fig. 3). However, in two dogs that received higher doses (Artemis and Charmander), we found substantial AP expression in the spleen, lung, and kidney, although AP expression in the liver and pancreas remained low (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Internal organ transduction following systemic AAV-8 injection in neonatal dogs. (A) Representative photomicrographs of AP histochemical staining from the liver, pancreas, spleen, lung and kidney. (B) Quantitative examination of AP activity in muscle lysate from the liver, pancreas, spleen, lung and kidney. (C) AAV genome copy quantification in the liver, pancreas, spleen, lung, and kidney.

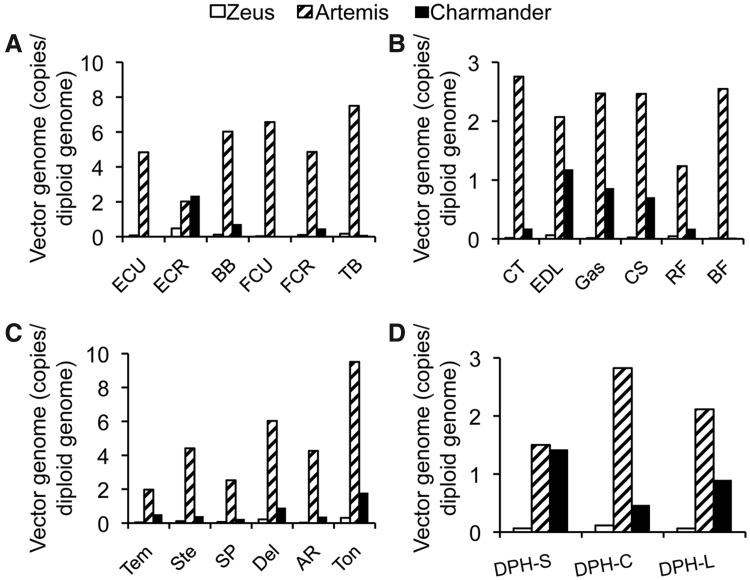

Examination of AAV genome copy in skeletal muscle and the heart

In general, the AAV genome copy number was very low for Zeus and very high for Artemis consistent with Zeus and Artemis having received the lowest and highest amount of virus, respectively (Figs. 2C and 4, Table 1). Interestingly, compared with that of Artemis, the AAV genome copy number was much reduced in Charmander, another dog that received high dose AAV-8 injection (Figs. 2C and 4, Table 1). Since the amount of virus Charmander received was only slightly lower (7.14×1014 vg/kg body weight) than what Artemis received (9.06×1014 vg particles/kg body weight), it is unlikely that the differences we saw in the AAV genome copy number was due to the difference of the inoculating dose. Considering the fact that Charmander was examined at 12 months after injection while Artemis was examined at 2.5 months after injection, it appeared that the harvesting time point might have contributed to the observed difference in the vector genome copy number.

FIG. 4.

Quantitative examination of the AAV genome copy number in skeletal muscles. (A) Results of vector genome quantification from forelimb muscles. ECU, extensor carpi ulnaris; ECR, extensor carpi radialis; BB, biceps brachii; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; FCR, flexor carpi radialis; TB, triceps brachii. (B) Results of vector genome quantification from hind limb muscles. CT, cranial tibialis; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; Gas, gastrocnemius; CS, cranial sartorius; RF, rectus femoris; BF, biceps femoris. (C) Results of vector genome quantification from head, neck, shoulder, chest and abdominal muscles. Tem, temporalis; Ste, sternocephalicus; SP, superficial pectoralis; Del, deltoid; AR, abdominal rectus; Ton, tongue. (D) Results of vector genome quantification from different parts of the diaphragm. DPH-S, sternal side diaphragm, DPH-C, costal side diaphragm, DPH-L, lumbar side diaphragm.

For Artemis, vector genome distribution also showed another peculiar pattern (Figs. 2C and 4). In the front limb and the heart, most muscle samples (except for the extensor carpi radialis and papillary muscle) showed a higher number of viral genome copy (more than four copies per diploid genome). However, viral genome copy number was less than three copies per cell for the diaphragm and hind limb muscles (Fig. 4). Nevertheless, the moderate difference in the AAV genome copy number seemed to have minimal impact on AP expression (Figs. 1 and 4).

Systemic AAV-8 injection in newborn dogs does not cause T-cell infiltration

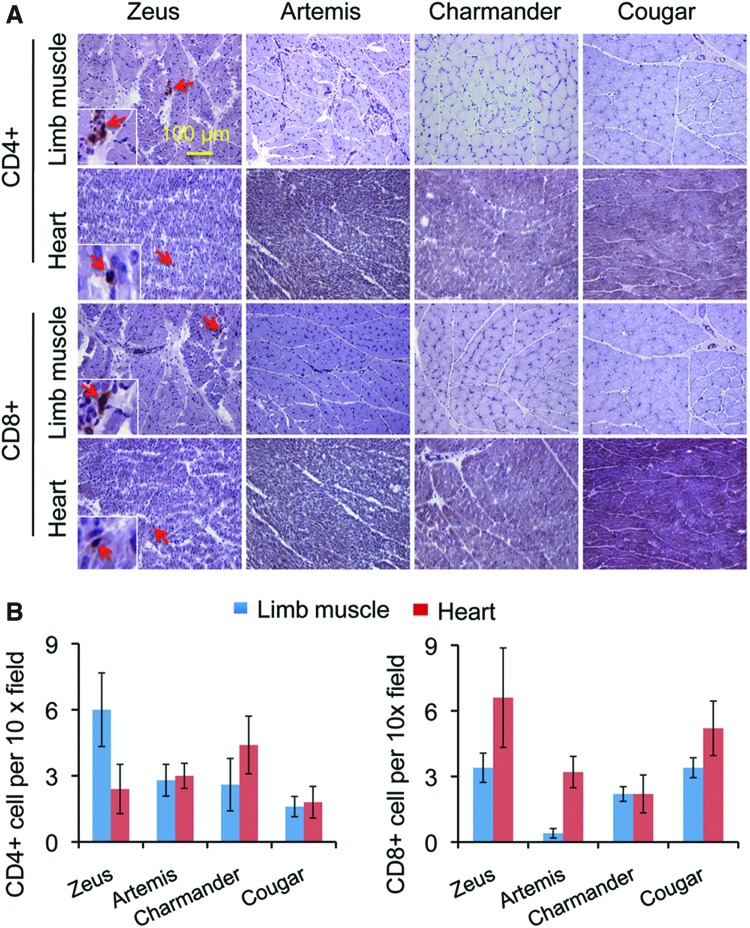

To determine whether bodywide AAV-8 transduction induces the T-cell response, we performed immunohistochemical staining for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the limb muscle and heart (Fig. 5). Muscles of an uninjected normal dog (Cougar) were used as controls. Rare occurring residential CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were detected in skeletal muscle and the heart irrespective of AAV injection (Fig. 5A). Quantification confirmed that systemic AAV-8 delivery did not induce T-cell infiltration (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Systemic AAV-8 injection in neonatal dogs dose not induce T cell infiltration in striated muscles. (A) Representative photomicrographs of immunohistostaining for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the limb muscle and the heart. Arrow, rare occurring residential T cells. Box insert, high power magnification of positively stained T cells in the respective image. (B) Quantitative examination of T cell number in the limb muscle and the heart. Cougar, a 2-year-old uninfected normal dog. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/hum

Neonatal systemic AAV-8 injection is safe in dogs

To determine whether systemic delivery of AAV-8 to newborn puppies causes untoward toxicity, we monitored growth curve and examined blood chemistry (Supplementary Fig. S1, Supplementary Data are available on line at www.liebertpub.com/hum; Table 2). Puppies that received AAV-8 injection showed a similar growth curve as that of uninjected siblings (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Table 2.

Blood Examination Resultsa

| |

Age (1.5 to 2 months) |

Age (12 months) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeus (1.5 months) | Artemis (2 months) | Uninfected control mean±SEM (range), n=11) | Charmander (12 months) | Uninfected control mean±SEM (range), n=4 | |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 11.3 | 10.8 | 11.4±0.1 (10.5–11.9) | 10.5 | 10.2±0.1 (10–10.4) |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 112 | 109 | 105.7±1.0 (99–110) | 111 | 112.8±0.9 (111–115) |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 13.2 | 9.2 | 8.4±0.3 (7.1–10.1) | 6.6 | 4.8±0.4 (4.2–5.8) |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 11.7 | 5 | 6.0±0.2 (5.2–7.1) | 4.2 | 4.4±0.1 (4.1–4.7) |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 149 | 148 | 140.1±1.2 (133–147) | 149 | 148.3±1.7 (146–152) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.6±0.1 (2.1–3.6) | 3.3 | 3.2±0.1 (3.1–3.4) |

| ALP (U/L) | 217 | 239 | 143.6±6.9 (111–198) | 267 | 60.0±24.9 (26–134) |

| ALT (U/L) | 45 | 42 | 18±2.8 (9–37) | 51 | 30.3±2.3 (25–36) |

| ALP/ALT ratio | 4.8 | 5.7 | 10±1.6 (3.8–22) | 5.2 | 2.2±1.1 (0.9–5.4) |

| Anion gap (mEq/L) | 34.7 | 25 | 23±0.7 (21–28) | 27 | 21.5±1.5 (18–24) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 179 | 186 | 277.5±22.4 (184–427) | 299 | 166.3±15.5 (135–187) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3±0.0 (0.2–0.7) | 1 | 0.9±0.0 (0.8–1.0) |

| GGT (U/L) | <3 | <3 | 1.3±0.7 (0–6) | 3 | 7.7±3.6 (0–16) |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.2±0.1 (1.7–2.7) | 2.8 | 2.5±0.2 (2.0–3.1) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 396 | 88 | 108.8±3.6 (89–126) | 94 | 91.0±3.7 (85–101) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1±0.0 (0.1–0.3) | 0 | 0.2±0.0 (0.2–0.3) |

| Total CO2 (mEq/L) | 14 | 19 | 17.4±1.4 (7–23) | 14 | 18.5±1.6 (14–21) |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4.8±0.2 (4.1–6.3) | 6.1 | 5.9±0.4 (5.2–6.9) |

| Urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 11 | 19 | 11.1±2.1 (4–22) | 23 | 14.8±2.7 (7–19) |

Abnormal value is marked in bold font. For Artemis and Charmander, blood was drawn while dogs were alive. In the case of Zeus, blood was drawn after the dog was euthanized.

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase.

In the blood chemistry study, we used the results from age-matched uninjected dogs as the normal controls (Table 2). The most remarkable change was the elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP). The ALP level was increased by approximately 1.5-, 1.7-, and 4.5-fold for Zeus, Artemis, and Charmander, respectively. Since our reporter gene is the human placental ALP gene, we suspect that ALP level elevation was due to AAV transduction rather than liver injury. To further investigate potential liver toxicity, we examined the alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level and ALP/ALT ratio. While the ALT level was increased in injected dogs, the ALP/ALT ratio was within the normal range in all three treated dogs (Table 2). Since the increase of the ALT level was proportional to the increase of the ALP level and also since the gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) level was within the normal range, we suspect that the observed change in the ALT level may likely reflect a nonspecific reaction rather than an indication of liver damage. In support of this, we did not see any histological lesions in the liver in all three AAV-injected dogs (Supplementary Fig. S2). As a matter of fact, microscopic examination of multiple internal organs (such as the spleen, pancreas, and kidney) did not show obvious tissue damage either (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Zeus showed abnormal values in several blood parameters including phosphorus, potassium, anion gap, and glucose (Table 2). Since blood was collected after euthanization in Zeus, we believe the observed differences may likely reflect postmortem changes rather than toxicity of AAV-8 injection.

Discussion

A breakthrough in heart gene therapy in recent years is the demonstration of robust myocardial transduction via tail vein injection in rodents using certain AAV serotypes (Lai and Duan, 2012). The ability to transduce the heart from a peripheral vein has tremendous advantages for cardiac gene therapy. It not only significantly reduces surgery risks associated with invasive heart gene delivery procedures but also raises the possibility of using gene therapy to treat heart diseases in remote/small clinics that do not have the facilities and/or support of a large medical center (Nashef et al., 2012). AAV-6, -8, and -9 are the serotypes most commonly used for systemic gene transfer (Bostick et al., 2007; Gregorevic et al., 2004; Inagaki et al., 2006; Pacak et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2005). Although all three serotypes have been shown to transduce rodent hearts, AAV-9 is especially advocated as a cardiotropic vector because of its extremely high potency in transducing the rodent heart (Inagaki et al., 2006; Lai and Duan, 2012; Wasala et al., 2011; Zincarelli et al., 2008).

To translate rodent study results to large mammals, we initially investigated systemic AAV-9 delivery in neonatal dogs (Yue et al., 2008, 2011). Much to everyone's surprise, AAV-9 failed to transduce the dog heart. In contrast to widespread gene transfer seen in the rodent heart (Bostick et al., 2007), we only found a few positive cells in the dog heart after jugular vein AAV-9 injection (Yue et al., 2008). Of the remaining two serotypes (AAV-6 and AAV-8), AAV-6 has been shown to transduce canine heart following local delivery (Bish et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2012). However, several recent findings suggest that AAV-6 is not ideal for systemic gene delivery in dogs. First, investigators including us have shown that there exists a strikingly high prevalence of AAV-6 neutralization antibody in dog blood (Rapti et al., 2012; Shin et al., 2012b). As a matter of fact, we have detected AAV-6 neutralization antibody (≥1:40) in the serum sample of every newborn puppy we examined (a total of 30 puppies; Shin et al., 2012b). Second, AAV-6 has been shown to form aggregates with galectin 3 binding protein, a highly glycosylated glycoprotein in dog sera (Denard et al., 2012). Importantly, this interaction hampers AAV transduction (Denard et al., 2012). Third, while efficient whole body transduction can be achieved with systemic AAV-8 or AAV-9 in the absence of additional drug treatment, systemic AAV-6 transduction may require co-administration of vascular endothelial growth factor and heparin (Bostick et al., 2007; Gregorevic et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2005). In summary, AAV-8 appeared to be the most logical next candidate to test in dogs.

Two groups have administered AAV-8 to newborn dogs (Koeberl et al., 2008; Sarkar et al., 2006). Sarkar et al. (2006) injected 6×1012 vg/kg of an AAV-8 factor VIII vector to two neonatal hemophilia dogs via the superficial temporal vein. Puppies were euthanized at 12 and 24 hr after vector administration. The authors only examined the liver, and they found vector-derived factor VIII transcripts at both time points but no measurable factor VIII activity in the plasma. Koeberl et al. (2008) used jugular vein injection. Three puppies with glycogen storage disease received 1×1013 vg/kg of an AAV-8 vector that expressed a therapeutic human glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) gene under transcriptional regulation of the human G6Pase minimal promoter. Treatment significantly prolonged survival in all three treated dogs. Liver biopsy also showed histological correction (Koeberl et al., 2008). Since treated dogs remained alive at the end of study, it was not clear whether heart and bodywide skeletal muscle transduction was achieved. Taken together, none of the published studies have explicitly examined bodywide gene transfer after systemic AAV-8 administration in newborn dogs.

To fill the gap, we delivered AAV-8 to three newborn puppies. In our previous AAV-9 study, we used vector doses between 1×1014 vg/kg and 2.5×1014 vg/kg (Yue et al., 2008, 2011). This dose range was well tolerated by neonatal puppies. For the AAV-8 study, we started with a dose of 1.35×1014 vg/kg (Zeus; Table 1). Necropsy was performed at the age of 1.5 months. Despite low transduction in a few selected muscles (such as the gastrocnemius and biceps femoris), most skeletal muscles were highly transduced throughout the body (Figs. 1 and 4). AAV-transduced cardiomyocytes were readily spotted in every part of the heart but in general, heart transduction was substantially lower than that of skeletal muscle (Fig. 2). Since the dose of 1.35×1014 vg/kg (AAV-8 for Zeus) was comparable to those used in our AAV-9 study (between 1×1014 vg/kg and 2.5×1014 vg/kg; Yue et al., 2008, 2011), we conclude that AAV-8 may be as efficient as (if not more efficient than) AAV-9 in neonatal dogs. This is exactly opposite to what has been reported in mice in which AAV-9 was found to be much more efficient than AAV-8 (Inagaki et al., 2006; Zincarelli et al., 2008).

Since our goal was to achieve robust heart transduction from a peripheral vein, we raised the dose to 9.06×1014 vg/kg (a 6.7-fold increase) and also extended the study duration to 2.5 months (Artemis; Table 1). To our knowledge, this dose was the highest ever administered in an animal. Despite infusion of huge amount of viral particles, we did not see any untoward reaction in the dog (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2, Table 2). As expected, higher AAV dose was accompanied by higher overall transduction (Figs. 1–4). Saturated expression was observed in every skeletal muscle we examined (Fig. 1). Muscle lysate AP activity assay also confirmed enhanced expression in almost every muscle. The only exception is the tongue, but the reason for this is not clear (Fig. 1E). Even muscles that were poorly transduced at the dose of 1.35×1014 vg/kg (such as the gastrocnemius and biceps femoris) now showed strong AP expression (Fig. 1). The most noteworthy change was in the heart (Fig. 2). Widespread transduction was seen throughout the entire heart (Fig. 2). AP expression was especially high in the ventricular myocardium (the free wall, septum, and papillary muscles; Fig. 2). We estimated that ≥50% cardiomyocytes expressed the AP gene in the ventricle (Fig. 2A). Besides striated muscles, increased AP expression was also found in the pancreas, spleen, lung, and kidney (Fig. 3). Interestingly, liver transduction appeared unaffected by vector dose and it remained low in Artemis (Fig. 3).

Having accomplished the goal of myocardial gene transfer using AAV-8, we next asked whether we could achieve persistent heart transduction with a lower vector dose. We reduced the AAV-8 dose by 20% to 7.14×1014 vg particles/kg body weight and administered it to the third dog (Charmander). A necropsy was performed 1 year later. Despite a one-fifth reduction of the viral dose and a much longer observation period, we still detected vigorous transduction in skeletal muscle and the heart (Figs. 1 and 2). On histochemical staining, skeletal muscle expression was essentially indistinguishable from that of Artemis, the dog that received the highest dose (Fig. 1). Muscle lysate assay also showed decent AP activity in all skeletal muscles studied (Fig. 1). Importantly, heart transduction remained sturdy in Charmander for at least 1 year (the end of experiment) without significant T-cell infiltration (Figs. 2 and 5). Taken together, our results suggest that peripheral vein AAV-8 injection is a safe approach to achieve strong and enduring transduction of all striated (skeletal and cardiac) muscles in the body of a large mammal. Our results also show that a higher viral dosage is needed in order to transduce the dog heart; for example, 1.35×1014 vg particles/kg body weight of AAV-8 only resulted in bodywide skeletal muscle transduction. A five-fold higher dose (7.14×1014 vg particles/kg body weight) of AAV-8 resulted in strong heart transduction. This finding reveals another difference between rodents and dogs. In mice, systemic injection of low-dose AAV-8 preferentially transduced the heart. Skeletal muscle transduction became apparent only at higher vector dose in mice (Inagaki et al., 2006). It is currently not clear why dogs respond differently from rodents. It is plausible that in addition to the potential differences in AAV receptor/coreceptor distribution in dog and rodent tissues, other anatomic/structural and physiological differences in the circulatory system (especially microcirculation) and/or muscle per se may have played a role. Future studies are needed to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

A frequent safety concern in systemic gene delivery is concomitant transduction of nontarget tissues. In our study, we detected only minimal liver transduction even at the highest vector dose (Fig. 4). However, transgene expression was observed in several internal organs especially the lung and kidney in two dogs that received higher doses (Fig. 4). Although beyond the scope of the current manuscript, several promising strategies have been proposed to increase the specificity of tissue targeting. These include the use of a tissue-specific promoter, vector genome engineering to include micro-RNA target sequence and molecular manipulation of viral capsid by direct evolution (Bartel et al., 2012; Brown and Naldini, 2009; Kelly and Russell, 2009; Li et al., 1999). Incorporation of these strategies may likely improve the safety profile for treating heart disease from peripheral vein using AAV-8 gene delivery in the future.

In summary, we have demonstrated for the first time the feasibility of whole-body striated muscle transduction in a large mammal. Robust and persistent cardiac gene transfer as demonstrated here may likely meet the therapeutic needs for treating many heart diseases. Future test of this technique in canine models of heart diseases (such as Duchenne cardiomyopathy) may pave the way of applying this technology to treat human heart diseases (Duan, 2011a; Fine et al., 2011; Lai and Duan, 2012).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) HL-91883 (DD), AR-49419 (DD), the Muscular Dystrophy Association (DD), and the Parent Project for Muscular Dystrophy (DD). We would like to thank Drs. Bruce Smith, Dawna Voelkl, Scott Korte, and Lonny Dixon for dog breeding and care. We thank Dr. James Wilson for providing AAV-8 Cap/Rep help plasmid, and we also thank Drs. Kevin Dellsperger, Michael Wang, and Ulus Atasoy for their help on interpretation of blood chemistry data. We thank Dr. Chady Hakim, Ms. Lauren Vince, Mr. Kasun Kodippili, and Mr. John Hu for technical assistance. We thank Mr. Sean X. Duan for help with English editing.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Bartel M.A. Weinstein J.R. Schaffer D.V. Directed evolution of novel adeno-associated viruses for therapeutic gene delivery. Gene Ther. 2012;19:694–700. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bish L.T. Sleeper M.M. Brainard B., et al. Percutaneous transendocardial delivery of self-complementary adeno-associated virus 6 achieves global cardiac gene transfer in canines. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1953–1959. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostick B. Ghosh A. Yue Y., et al. Systemic AAV-9 transduction in mice is influenced by animal age but not by the route of administration. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1605–1609. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B.D. Naldini L. Exploiting and antagonizing microrna regulation for therapeutic and experimental applications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:578–585. doi: 10.1038/nrg2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denard J. Beley C. Kotin R., et al. Human galectin 3 binding protein interacts with recombinant adeno-associated virus type 6. J. Virol. 2012;86:6620–6631. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00297-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D. Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene therapy: lost in translation? Res. Rep. Biol. 2011a;2:31–42. doi: 10.2147/RRB.S13463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D. Gene delivery to the heart: an updated review on vectors and methods. J. Gene Med. 2011b;13:556. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine D.M. Shin J.H. Yue Y., et al. Age-matched comparison reveals early electrocardiography and echocardiography changes in dystrophin-deficient dogs. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2011;21:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorevic P. Blankinship M.J. Allen J.M., et al. Systemic delivery of genes to striated muscles using adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat. Med. 2004;10:828–834. doi: 10.1038/nm1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki K. Fuess S. Storm T.A., et al. Robust systemic transduction with AAV9 vectors in mice: efficient global cardiac gene transfer superior to that of AAV8. Mol. Ther. 2006;14:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa K. Tilemann L. Fish K. Hajjar R.J. Gene delivery methods in cardiac gene therapy. J. Gene Med. 2011;13:566–572. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaski B.E. Jessup M.L. Mancini D.M., et al. Calcium upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in cardiac disease (Cupid Trial), a first-in-human phase 1/2 clinical trial. J. Card. Fail. 2009;15:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessup M. Greenberg B. Mancini D., et al. Calcium Upregulation by Percutaneous Administration of Gene Therapy in Cardiac Disease (CUPID): a phase 2 trial of intracoronary gene therapy of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2011;124:304–313. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.022889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz M.G. Fargnoli A.S. Tomasulo C.E., et al. Model-specific selection of molecular targets for heart failure gene therapy. J. Gene Med. 2011;13:573–586. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly E.J. Russell S.J. MicroRNAs and the regulation of vector tropism. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:409–416. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeberl D.D. Pinto C. Sun B., et al. Aav vector-mediated reversal of hypoglycemia in canine and murine glycogen storage disease type Ia. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:665–672. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratlian R.G. Hajjar R.J. Cardiac gene therapy: from concept to reality. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2012;9:33–39. doi: 10.1007/s11897-011-0077-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y. Duan D. Progress in gene therapy of dystrophic heart disease. Gene Ther. 2012;19:678–685. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Eastman E.M. Schwartz R.J. Draghia-Akli R. Synthetic muscle promoters: activities exceeding naturally occurring regulatory sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999;17:241–245. doi: 10.1038/6981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashef S.A. Roques F. Sharples L.D., et al. Euroscore II. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012;41:734–744. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs043. discussion 744–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacak C.A. Mah C.S. Thattaliyath B.D., et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 leads to preferential cardiac transduction in vivo. Circ. Res. 2006;99:e3–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237661.18885.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapti K. Louis-Jeune V. Kohlbrenner E., et al. Neutralizing antibodies against AAV serotypes 1, 2, 6, and 9 in sera of commonly used animal models. Mol. Ther. 2012;20:73–83. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar R. Mucci M. Addya S., et al. Long-term efficacy of adeno-associated virus serotypes 8 and 9 in hemophilia a dogs and mice. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006;17:427–439. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J.H. Yue Y. Duan D. Recombinant adeno-associated viral vector production and purification. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012a;798:267–284. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-343-1_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J.H. Yue Y. Smith B. Duan D. Humoral immunity to AAV-6, 8, and 9 in normal and dystrophic dogs. Hum. Gene Ther. 2012b;23:287–294. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J.H. Yue Y. Srivastava A., et al. A simplified immune suppression scheme leads to persistent micro-dystrophin expression in Duchenne muscular dystrophy dogs. Hum. Gene Ther. 2012c;23:202–209. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B.F. Yue Y. Woods P.R., et al. An intronic LINE-1 element insertion in the dystrophin gene aborts dystrophin expression and results in Duchenne-like muscular dystrophy in the corgi breed. Lab. Invest. 2011;91:216–231. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. Zhu T. Qiao C., et al. Adeno-associated virus serotype 8 efficiently delivers genes to muscle and heart. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:321–328. doi: 10.1038/nbt1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasala N.B. Shin J.H. Duan D. The evolution of heart gene delivery vectors. J. Gene Med. 2011;13:557–565. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y. Ghosh A. Long C., et al. A single intravenous injection of adeno-associated virus serotype-9 leads to whole body skeletal muscle transduction in dogs. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1944–1952. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y. Shin J.-H. Duan D. Whole body skeletal muscle transduction in neonatal dogs with AAV-9. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;709:313–329. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-982-6_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X. McTiernan C.F. Rajagopalan N., et al. Immunosuppression decreases inflammation and increases AAV6-hSERCA2a-mediated SERCA2a expression. Hum. Gene Ther. 2012;23:722–732. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zincarelli C. Soltys S. Rengo G. Rabinowitz J.E. Analysis of AAV serotypes 1-9 mediated gene expression and tropism in mice after systemic injection. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1073–1080. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.