Abstract

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric illnesses and are associated with heightened stress responsiveness. The neuropeptide oxytocin (OT) has garnered significant attention for its potential as a treatment for anxiety disorders; however, the mechanism mediating its effects on stress responses and anxiety is not well understood. Here we used acute hypernatremia, a stimulus that elevates brain levels of OT, to discern the central oxytocinergic pathways mediating stress responsiveness and anxiety-like behavior. Rats were rendered hypernatremic by acute administration of 2.0 M NaCl and had increased plasma sodium concentration, plasma osmolality, and Fos induction in OT-containing neurons relative to 0.15 M NaCl-treated controls. Acute hypernatremia decreased restraint-induced elevations in corticosterone and created an inhibitory oxytocinergic tone on parvocellular neurosecretory neurons within the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. In contrast, evaluation of Fos immunohistochemistry determined that acute hypernatremia followed by restraint increased neuronal activation in brain regions receiving OT afferents that are also implicated in the expression of anxiety-like behavior. To determine whether these effects were predictive of altered anxiety-like behavior, rats were subjected to acute hypernatremia and then tested in the elevated plus maze. Relative to controls given 0.15 M NaCl, rats given 2.0 M NaCl spent more time in the open arms of the elevated plus maze, suggesting that acute hypernatremia is anxiolytic. Collectively the results suggest that acute elevations in plasma sodium concentration increase central levels of OT, which decreases anxiety by altering neuronal activity in hypothalamic and limbic nuclei.

Stressful life events are risk factors for anxiety disorders, which are among the most prevalent psychopathologies in the United States (1, 2). Oxytocin (OT) is a highly conserved neuropeptide expressed within a subset of hypothalamic neurons, and studies conducted in humans and animals have found that within the brain, OT is anxiolytic and promotes resiliency to stress (3–5). Consequently, OT is currently being tested as a potential therapeutic for anxiety disorders; however, the central pathways mediating the influence of endogenously generated OT on stress responsiveness and mood remain to be discerned.

In the rat, OT is primarily produced by magnocellular neurons in the supraoptic (SON) and paraventricular (PVN) nuclei of the hypothalamus, and the activation of these neurons is strongly influenced by the plasma sodium concentration (pNa+). During hypernatremia the increased pNa+ drives the activation of the SON and PVN neurons to promote renal water reabsorption and sodium excretion by elevating systemic levels of arginine vasopressin (AVP) and augmenting sympathetic nervous system activity, respectively (6, 7). Less well known is that elevations in the pNa+ activate magnocellular neurons in the SON and PVN to cause the release of OT into the systemic circulation (8, 9). Subsequent to its systemic release, central levels of OT become greatly elevated, and this effect is sustained (10–12). In other words, acute hypernatremia produces robust and long-lasting elevations in brain levels of OT, which may impact responsiveness to temporally contiguous stressors.

Here we use acute elevations in the pNa+ to increase the central concentration of OT in male rats and subsequently examine stress responsiveness and anxiety-like behavior. As expected, administration of hypertonic saline elevated pNa+ and activated OT-containing neurons in the SON and PVN. Consistent with previous studies (9), acute hypernatremia decreased restraint-induced elevations in corticosterone (CORT). We performed whole-cell patch clamp recordings to test the hypothesis that acute hypernatremia blunts activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis by exerting an inhibitory oxytocinergic tone on parvocellular neurons in the PVN that have intrinsic properties consistent with previously described type II/neurosecretory neurons (see Materials and Methods). Neuroanatomical studies used Fos immunohistochemistry to evaluate the pattern of neuronal activation after acute hypernatremia and restraint. Interestingly, acute hypernatremia followed by restraint elicited differential patterns of activation in brain regions receiving OT afferents that are also implicated in the expression of anxiety-like behavior. To determine whether these effects were predictive of altered anxiety-like behavior, rats were subjected to acute hypernatremia and then tested in the elevated plus maze (EPM). The results suggest that acute elevations in the pNa+ increase central levels of OT, which alters neuronal activity in brain nuclei mediating stress responsiveness and mood.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult (6–8 weeks, 250–300 g) and juvenile [postnatal day (P) 18–25, 30–35 g)] male Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, Indiana) were individually housed on a 12-hour light, 12-hour dark schedule with ad libitum access to pelleted rat chow (Harlan Teklad, Madison, Wisconsin) and water, except where otherwise noted. Adult rats were used for all aspects of the study with the exception of experiments using in vitro electrophysiology. All animal procedures were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to the animal welfare guidelines issued by the National Institutes of Health.

Restraint stress

Rats were administered 1 mL of 0.15 M NaCl (n = 21) or 2.0 M NaCl (n = 20) sc and returned to their home cages in which water was made unavailable. Injections of 0.15 M NaCl and 2.0 M NaCl were preceded by the administration of 2% lidocaine (0.05 mL) to minimize pain and irritation. Sixty minutes after the injections, rats were subdivided into 4 groups: 1) 0.15 M NaCl/nonrestraint, 2) 2.0 M NaCl/nonrestraint, 3) 0.15 M NaCl/restraint, and 4) 2.0 M NaCl/restraint. After 60 minutes, rats were either placed into clear plastic restrainers or remained in their home cages and tail blood samples (250–300 μL) were quickly taken. After 60 minutes of restraint, tail blood samples were taken, and subsequently rats were released from the plastic restrainers and recovered in their home cages until a final tail blood sample was taken 120 minutes after the onset of restraint (or 180 minutes after the injections of 0.15 M NaCl or 2.0 M NaCl). Blood samples were collected into microcapillary tubes or chilled tubes containing EDTA and centrifuged at 3500 rpm. Microcapillary samples were measured for hematocrit, and plasma was extracted from chilled tubes and stored at −80°C until analyzed for plasma proteins, pNa+, plasma osmolality (pOsm), and CORT. After the collection of blood samples at 120 minutes after the onset of restraint (or 180 minutes after the injections of 0.15 M NaCl or 2.0 M NaCl), rats were overanesthetized with pentobarbital and perfused with 0.15 M NaCl followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were collected, postfixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, and then submerged in 30% sucrose and stored at 4°C prior to processing for immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

Four series of 30-μm coronal brain sections were taken on a Leica CM3050 S cryostat (Leica, Buffalo Grove, Illinois) and placed in cryoprotective solution for storage at −20°C. A series of free-floating sections were used to visualize Fos protein immunoreactivity. Sections were washed in 50 mM potassium PBS (KPBS) to remove cryoprotectant and then incubated in 0.3% H2O2 for 15 minutes followed by a rinse in 50 mM KPBS. Sections were then placed in a blocking solution (50 mM KPBS with 2% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% Triton X-100) at room temperature and then incubated in anti-Fos (1:2500; sc-52 rabbit anti-Fos; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California) at 4°C in the blocking solution overnight. The following day, sections were brought to room temperature, rinsed, and incubated for 45 minutes in biotinylated goat antirabbit (1:500; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California) made in a blocking solution. Subsequently, sections were rinsed and then incubated for 60 minutes in avidin-biotin complex (Vectastain ABC Elite, 1:500; Vector Laboratories). After rinsing, sections were developed in a 3,3 diaminobenzidine solution containing H2O2 and nickel (Vector SK-4100; Vector Laboratories), mounted onto microscope slides, placed in graded ethanol and xylene solutions, and coverslipped.

Sections through the PVN and SON were isolated from another series of brain sections and were processed for qualitative immunofluorescent labeling of Fos and OT. Initial rinses in 50 mM KPBS were performed to remove cryoprotectant followed by 15 minutes incubation in 2% H2O2 and 0.3% glycine. Sections were then rinsed and blocked for 1 hour in a solution of 50 mM KPBS with 2% normal goat serum and 0.2% Triton X-100 at room temperature. Subsequently, sections were incubated in anti-Fos (1:1000) overnight at 4°C in the blocking solution. The following day, rinsed sections were incubated in secondary antibody for 2 h (Cy3 antirabbit 1:500; Jackson ImmnoResearch, West Grove, Pennsylvania). Subsequently, sections were rinsed and then placed in a blocking solution containing mouse anti-OT neurophysin 1:300 (a gift from Dr Harold Gainer, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland) overnight at 4°C (13). The next day, rinsed sections were incubated in secondary antibody (Alexa-488 donkey-antimouse, 1:500; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) in blocking solution for 1 hour. Sections were then rinsed and sequentially mounted onto microscope slides and coverslipped with polyvinyl alcohol.

Imaging and analysis

Brain regions of interest (ROIs) were identified using anatomical landmarks and coordinates described by Paxinos and Watson [(14); see Table 1)]. Bright-field and fluorescence images were captured using a Zeiss AxioImager M2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, New York). Image capture and analysis were performed using the highest magnification that allowed for an ROI to fit within the focal field. Images of brain sections were analyzed for number of Fos-positive nuclei using Image J (National Institutes of Health). Captured images were converted into gray-scale and binary formats, and thresholds for black and white balance were adjusted to the same level for each ROI. Counts were taken from matched sections representing the ROI, and in the case of bilateral nuclei, counts were taken from 1 side. The number of Fos-positive nuclei for each brain region was averaged, and the group means for each area were calculated for the following groups: 1) 0.15 M NaCl/nonrestraint, 2) 2.0 M NaCl/nonrestraint, 3) 0.15 M NaCl/restraint, and 4) 2.0 M NaCl/restraint.

Table 1.

Abbreviations and Coordinates Used for Brain Regions of Interest

| Region of Interest | Abbreviation | Rostral-Caudal Coordinates From Bregma, mm |

|---|---|---|

| Oval capsule of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis | BNSToc | 0.24 to − 0.24 |

| Ventral-lateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis | BNSTvl | 0.36 to − 0.24 |

| Lateral division of the central nucleus of the amygdala | CeL | − 2.04 to − 2.92 |

| Medial division of the central nucleus of the amygdala | CeM | − 2.04 to − 2.92 |

| Dorsal medial hypothalamus | DMH | − 2.52 to − 3.12 |

| Infralimbic cortex | IL | 3.00 to 2.52 |

| Prelimbic cortex | PrL | 3.00 to 2.52 |

| Ventral portion of the lateral septal nucleus | LVS | 1.2 to 0.48; −0.24 |

| Organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis | OVLT | 0.60–0.36 |

Testing anxiety-like behavior

To determine the effect of acute hypernatremia on mood, another group of adult rats was injected with 0.15 M NaCl (n = 16) or 2 M NaCl (n = 15) and water deprived as described. One hour later, rats were tested in a 44- × 44-inch EPM as done previously (9). Rats were placed in the center square of the EPM facing an open arm and permitted to explore the maze for 5 minutes. The EPM testing was conducted during the light phase. During testing each rat was videotaped from overhead, and a computerized tracking system (TopScan; CleverSys, Reston, Virginia) was used to measure the time spent in each arm of the EPM and the total distance traveled.

In vitro whole-cell recording and identification of parvocellular neurosecretory neurons in the acute slice preparation

Male Sprague Dawley rats between the ages of P18 and P25 received injections of 0.2 mL of 0.15 M NaCl or 2.0 M NaCl sc, and subsequently, water was made unavailable. Each injection was preceded by administration of lidocaine to minimize pain and irritation. Sixty minutes later, rats were administered ketamine (80–100 mg/kg, ip) and were rapidly decapitated using a small animal guillotine. The brain was quickly removed, and coronal sections (300 μm thick) through the PVN were made using a vibratome (Pelco, Redding, California). Slices were incubated for 30 minutes at 30–35°C and then allowed to reach room temperature (for a minimum of 30 minutes). During cutting and incubation, slices were kept in a dissecting solution that was saturated with 95% O2-5% CO2 and contained (in millimoles): 124 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.23 NaH2PO4, 2.5 MgSO4, 10 D-glucose, 1 CaCl2, and 25.9 NaHCO3. For whole-cell recording, slices were transferred to a slice chamber in which they were continuously perfused at a rate of 2 mL/min with artificial cerebrospinal fluid that contained (in millimoles): 126 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 1.5 MgSO4, 11 D-glucose, 2.4 CaCl2, and 25.9 NaHCO3. This solution was saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, and bath temperature was maintained at 30°C. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were performed using micropipettes pulled from a borosilicate glass using a Flaming/Brown electrode puller (Sutter P-97; Sutter Instruments, Novato, California). Electrode tip resistance was between 4 and 6 MΩ when filled with an internal solution that contained (in millimoles): 130 K-gluconate, 10 KCl, 10 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 2 Na2ATP, 0.3 NaGTP, and 10 HEPES. This solution was pH adjusted to 7.3 using KOH and volume adjusted to 285–300 mOsm. To isolate parvocellular neurosecretory neurons, we recorded from neurons located in rostral and medial areas of the PVN that had a specific membrane resistance of 50 MΩ/pF or greater, that did not express a transient outwardly rectifying potassium conductance, and that also did not demonstrate a robust low threshold spike during a standard current voltage experiment or after a hyperpolarizing conditioning pulse of 300-600 milliseconds to approximately −100 mV (15–19). Among these neurons, mean input resistance was 880 ± 113 MΩ, and mean whole-cell capacitance was 10.8 ± 0.90 pF. Bath application of [d(CH2)51,Tyr(Me)2,Orn8]-oxytocin (OTR-A, 1 μM), an oxytocin receptor antagonist, was used to test for the presence of an oxytocinergic tone in parvocellular neurons in slices extracted from control and hypernatremic animals.

Plasma analyses

Plasma proteins and hematocrit were determined using a refractometer and microcapillary reader, respectively. Plasma sodium was determined using an autoflame photometer (Instrumentation Laboratory, Lexington, Massachusetts). Plasma osmolality was determined using a VAPRO vapor pressure osmometer (Wescor, Logan, Utah). The plasma CORT concentration was determined using an 125I kit from MP Biomedicals (Santa Ana, California) as done previously (9, 20, 21).

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The plasma CORT concentration and Fos-positive nuclei were analyzed with a 2-factor ANOVA. The hematocrit, plasma protein, pOsm, pNa+, time spent in the open arms of the EPM, and the distance traveled in the EPM were assessed with a 2-tailed t test. The main effects or interactions (P < .05) were assessed with a Fisher least significant differences test. For the electrophysiological studies, a 2-tailed, 1-sample t test was used to determine whether the antagonism of oxytocin receptors had a significant effect on current density [null hypothesis, Δ(pa/pF) = 0], whereas an unpaired, 2-tailed, 2-sample t test was used to compare the effects of 0.15 M NaCl or 2 M NaCl on oxytocin receptor blockade.

Results

Administration of hypertonic NaCl elevates pNa+ and pOsm but attenuates the CORT response to restraint

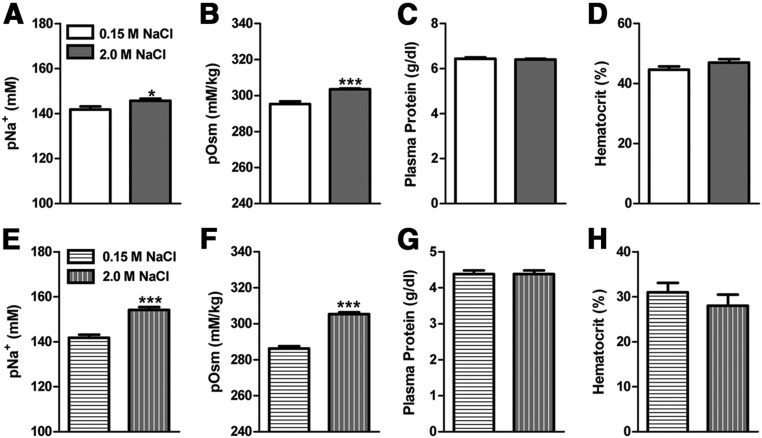

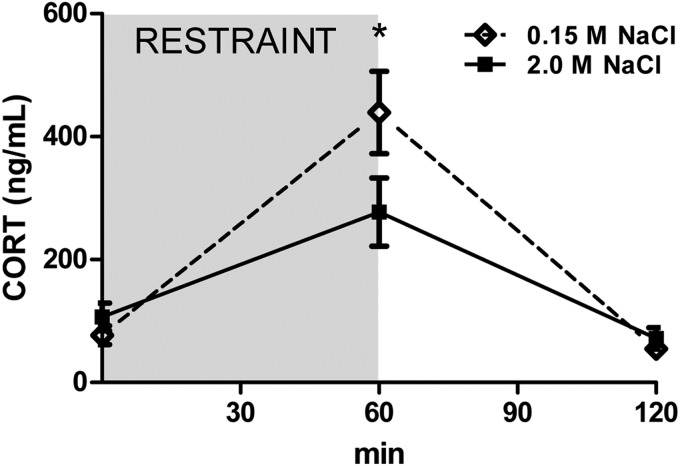

Figure 1 presents the pNa+, pOsm, plasma protein, and hematocrit levels of adult (Figure 1, A–D) and P18-25 (Figure 1, E–H) rats 60 minutes after receiving injections of 0.15 M NaCl or 2.0 M NaCl. The administration of 2.0 M NaCl significantly increased pOsm and pNa+ relative to controls, but plasma protein and hematocrit levels were similar between hypernatremic and control rats. In regard to the plasma CORT concentration, there was a significant time × condition interaction [F(2, 65) = 3.78, (P < .05)]. As can be seen in Figure 2, restraint significantly increased plasma CORT at 60 minutes (P < .05) relative to the other time points. Interestingly, the restraint-induced elevation of plasma CORT was suppressed in rats given 2.0 M NaCl relative to controls. Specifically, rats administered 2.0 M NaCl had significantly lower CORT at 60 minutes relative to rats given control injection of 0.15 M NaCl.

Figure 1.

Plasma measurements taken from adult (top panels) and P18–25 (bottom panels) rats 60 minutes after injection of 0.15 M or 2.0 M NaCl. Injection of 2.0 M NaCl significantly increased plasma osmolality and pNa+ relative to control injection of 0.15 M NaCl. *, P < .05; ***, P < .001.

Figure 2.

Acute hypernatremia attenuates the HPA response to restraint stress. Restraint elevated plasma CORT levels; however, 2.0 M NaCl administration blunted this response relative to 0.15 M NaCl. *, P < .05.

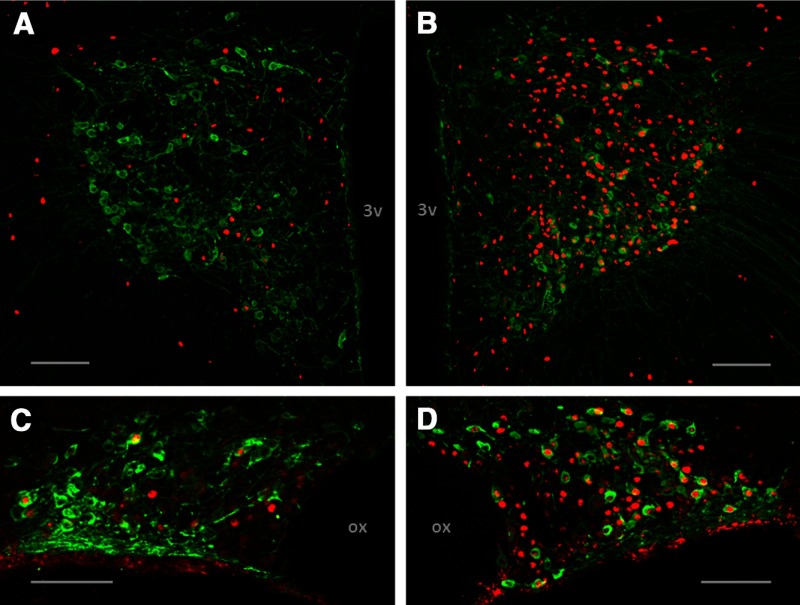

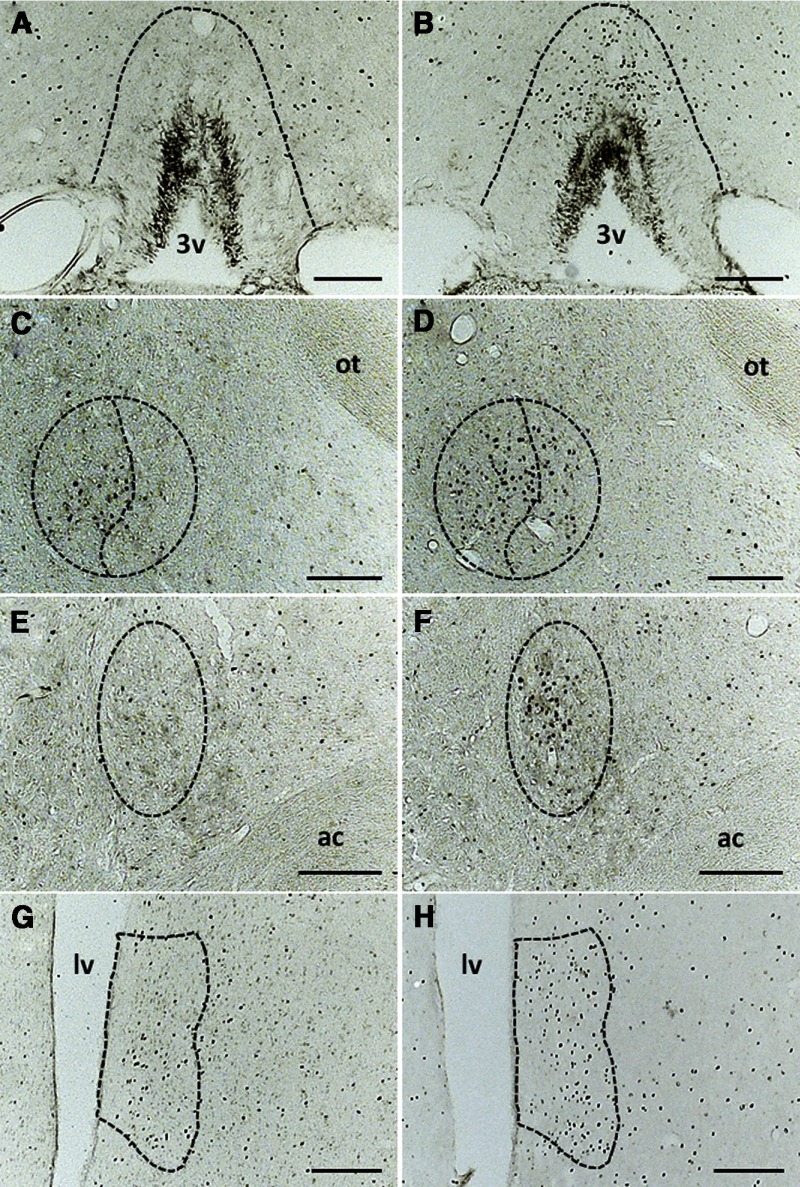

Immunohistochemical qualification of OT and Fos within the SON and PVN

Figure 3 displays the relative increase in Fos immunoreactivity in OT-labeled neurons within the SON and PVN. Rats treated with 0.15 M NaCl and restraint exhibited scant colocalization of OT and Fos in the PVN and SON (Figure 3, A and C). The administration of 2.0 M NaCl and restraint robustly elicited Fos induction in OT-containing neurons in these nuclei (Figure 3, and D).

Figure 3.

Acute hypernatremia followed by restraint activates OT-containing neurons. A, Representative photomicrograph of a coronal section through the PVN depicting Fos induction (red nuclei) in OT (green cell bodies) containing neurons after the administration of 0.15 M NaCl and restraint. B, Representative photomicrograph of a coronal section through the PVN depicting Fos induction in OT-containing neurons after 2 M NaCl and restraint. C, Representative photomicrograph of a coronal section through the SON depicting Fos induction in OT containing neurons after 0.15 M NaCl and restraint. D, Representative photomicrograph of a coronal section through the SON depicting Fos induction in OT-containing neurons after 2 M NaCl and restraint. 3v, third ventricle, ox; optic chiasm. Scale bars, 100 μm.

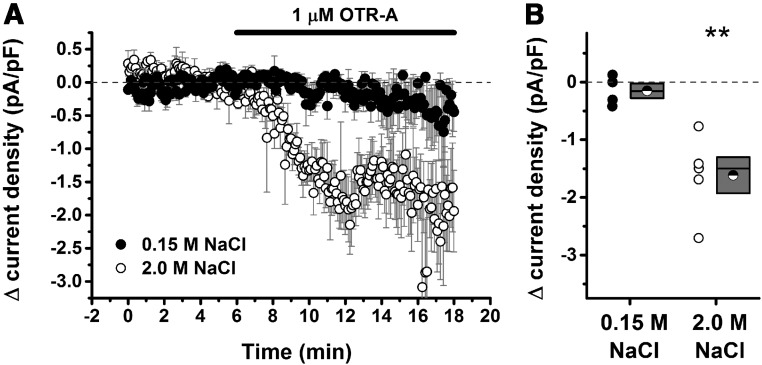

Acute hypernatremia creates an inhibitory oxytocinergic tone

Previous studies have indicated that hypernatremia-induced activation of magnocellular neurons leads to dendritic release of OT (10–12). This raises the possibility that hypernatremia may initiate OT-mediated paracrine signaling within the PVN that influences the excitation of parvocellular neurosecretory neurons controlling the HPA axis. To test this hypothesis, we used single-cell recording techniques in an acute PVN slice preparation to quantify the extent to which parvocellular neurosecretory neurons were under tonic OT receptor-mediated inhibition in rats that had previously been injected with 0.15 M NaCl or 2.0 M NaCl. Our results indicate that injection of 2.0 M NaCl 1 hour prior to euthanasia created a clear OT receptor-mediated inhibitory tone on parvocellular neurosecretory neurons that was not apparent in rats that received injection of 0.15 M NaCl (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Acute hypernatremia creates an inhibitory oxytocinergic tone. Parvocellular neurosecretory neurons in the PVN (see Materials and Methods) were voltage clamped at −70 mV, and current density (picoamp per picofarad [pA/pF]) required to hold the cell at −70 mV was monitored over time. A, Illustration of the change in current density as observed during bath application of 1 μM OTR-A, an oxytocin receptor antagonist. Filled circles illustrate the result of this experiment in slices taken from rats that received 0.15 M NaCl 1 hour prior to euthanasia. Open circles illustrate the result of an identical experiment conducted with slices taken from rats that received 2.0 M NaCl. A decrease in current density is indicative of removal of an inhibitory oxytocinergic tone but was observed only in slices taken from hypernatremic rats. B, Summary data for all cells that met criteria for this experiment. For each group, a scatter plot showing change in current density for every cell tested is presented to the left of a box plot. For this analysis and for data presented in panel A, the change in current density was calculated by subtracting the current density measured during the baseline period (from 3 to 6 minutes relative to the X-axis in panel A) from the current density observed during a 3-minute period immediately after a 5-minute wash-in of the antagonist (eg, from 11 to 14 minutes relative to the X-axis in panel A). Box plots for each group illustrate the mean (half-filled circle), the median (horizontal line with in the box), and the SEM (top and bottom edges of the box) are shown. The double asterisks over the 2.0 M NaCl group indicate that the mean change in current density observed in this group is significantly greater than 0 (P = .007) and also significantly greater than the change observed in the 0.15 M NaCl group (P = .006). By contrast, the mean change observed in the 0.15 M NaCl group was not significantly different from 0 (P = .32). **, P < .01.

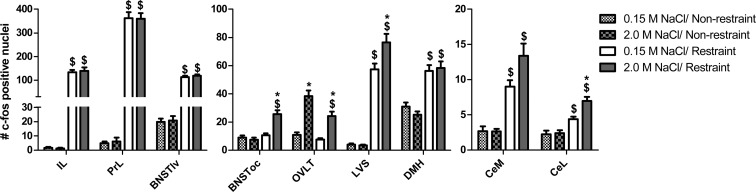

Acute hypernatremia combined with restraint increases neuronal activation within discrete brain regions

Figure 5 displays the average number of Fos-positive nuclei observed in the following 4 groups: 1) 0.15 M NaCl/nonrestraint, 2) 2.0 M NaCl/nonrestraint, 3) 0.15 M NaCl/restraint, and 4) 2.0 M NaCl/restraint. Relative to 0.15 M-treated controls, the dorsal cap of the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (OVLT) was robustly activated by hypernatremia, independent of restraint challenge [interaction: F(1, 37) = 4.23, P < .05; Figures 5 and 6, A and B]. There was an interaction between the administration of 2.0 M NaCl and restraint, such that rats subjected to both exhibited increased Fos immunoreactivity within the lateral subdivision of the central nucleus of the amygdala [CeL; F(1, 37) = 6.05; P < .05] compared with controls (Figures 5, 6C, and 6D). Likewise, 2.0 M NaCl combined with restraint elicited significantly more Fos within the oval capsule of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis [BNSToc; F(1, 35) = 16.46; P < .0001; Figures 5, 6E, and 6F] and the ventral part of the lateral septal nucleus [LVS; F(1, 35) = 4.85; P < .05; Figures 5, 6G, and 6H] relative to controls. In contrast, although there was a main effect of restraint on Fos immunoreactivity within the medial subdivision of the central nucleus of the amygdala [CeM; F(1, 37) = 47.17; P < .0001], dorsal-medial hypothalamus [DMH; F(1, 37) = 48.96; P < .0001], infralimbic cortex [IL; F(1, 30) = 209.86; P < .0001], prelimbic cortex [PrL; F(1, 30) = 334.9; P < .0001], and ventral-lateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis [BNSTvl; F(1, 35) = 345.52; P < .0001], hypernatremia did not alter the number of Fos-positive nuclei within these regions (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Acute hypernatremia increases restraint-induced neuronal activation in specific forebrain nuclei. Administration of 2.0 M NaCl prior to restraint significantly increased Fos expression in CeL, LVS, OVLT, and BNSToc but had no effect in the CeM, DMH, IL, PrL, and BNSTvl relative to controls given 0.15 M NaCl with restraint. *, Significant effect of 2.0 M NaCl, relative to the respective (nonrestraint or restraint) 0.15 M NaCl-treated group (P < .05); $, significantly different from the respective (0.15 M NaCl or 2.0 M NaCl treated) nonrestraint group (P < .05). Error bars indicate SEM.

Figure 6.

Representative photomicrographs of the coronal sections of the forebrain nuclei impacted by acute hypernatremia and restraint. Coronal sections through the OVLT (A and B), CeM and CeL (C and D), BNSToc (E and F), and LVS (G and H). A, Coronal section through the OVLT showing that Fos immunoreactivity is scant after 0.15 M NaCl and restraint. B, Administration of 2.0 M NaCl followed by restraint produces strong Fos immunoreactivity that is localized to the dorsal cap of the OVLT. C, Fos induction in the CeM and CeL is modest and diffuse after the administration of 0.15 M NaCl and restraint. D, Delivery of 2.0 M NaCl significantly increases Fos induction in the CeL with a nonsignificant trend for increased Fos in the CeM. E, The oval capsule of the BNST has modest Fos expression after 0.15 M NaCl and restraint. F, In contrast, treatment with 2.0 M NaCl and restraint produces strong Fos expression within a compact group of neurons in the oval capsule of the BNST. Although 0.15 M NaCl and restraint elicit Fos induction in the LVS (G), this occurs to a greater extent subsequent to the treatment with 2.0 M NaCl and restraint (H). ac, anterior commissure; lv, lateral ventricle; ot, optic tract; 3v, third ventricle. Scale bars, 200 μm.

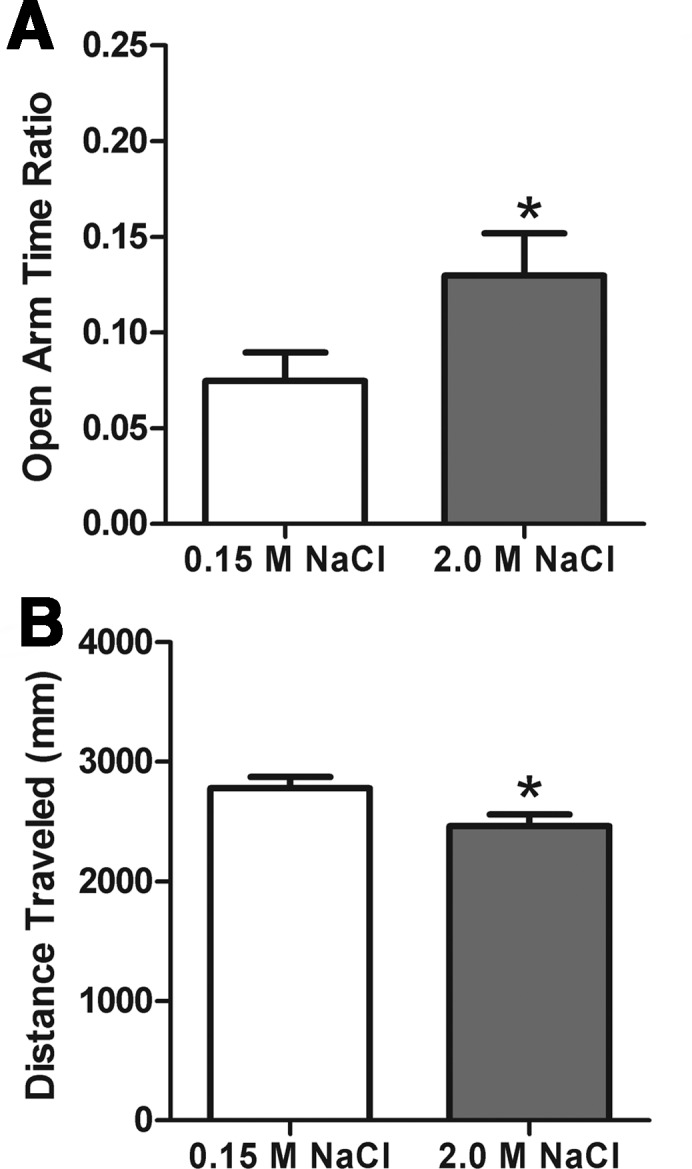

Acute hypernatremia reduces anxiety-like behavior assessed in the EPM

Rats administered 2.0 M NaCl spent significantly more time (P < .05) in the open arms of the EPM than rats given control injections of 0.15 M NaCl (Figure 7A). Despite this decreased anxiety-like behavior, rats given 2.0 M NaCl had reduced locomotor activity (less distance traveled in the EPM) relative to controls (P < .05; Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Acute hypernatremia attenuates anxiety-like behavior. Rats treated with 2.0 M NaCl (A) spent more time in the open arms of the EPM, and they had reduced locomotor activity (B) relative to the controls administered 0.15 M NaCl. *, P < .05.

Discussion

The present study used acute hypernatremia to investigate central oxytocinergic circuits mediating stress responsiveness and anxiety-like behavior. Acute hypernatremia activated oxytocinergic neurons as demonstrated by colocalization of OT and Fos in the PVN and SON of rats treated with 2.0 M NaCl. Hypernatremic rats were exposed to stress when central levels of OT are known to be elevated and were resilient to stressors when compared with normonatremic controls. Specifically, administration of 2.0 M NaCl attenuated the CORT response to restraint and created an inhibitory oxytocinergic tone on parvocellular neurosecretory neurons within the PVN. Acute hypernatremia combined with restraint also elicited greater Fos induction in the CeL, LVS, and BNSToc, brain regions known to receive OT afferents. Rats were tested in the EPM to determine whether the increased Fos that was observed in hypernatremic rats was predictive of altered anxiety-like behavior. Indeed, rats given 2.0 M NaCl spent more time in the open arms of the EPM relative to controls, indicating that acute hypernatremia is anxiolytic. Taken together, the results suggest that acute hypernatremia promotes resiliency to psychogenic stressors, in part, by altering neuronal activation within hypothalamic and limbic nuclei, an effect that may be mediated by the central release of OT.

Administration of 2.0 M NaCl increased pNa+ and pOsm of adult rats by 2.5% and 2.7%, respectively, and comparison with other models of hypernatremia provides insight toward the magnitude of these changes. For example, rat models that increase pNa+ levels greater than 165 mM or those that elevate pOsm greater than 10% are associated with robust fluid intake (>60 mL/d) augmented the systemic AVP and accumulation of brain osmolytes (22–24). The increases in pNa+ and pOsm observed in our study are known to increase water intake and the release of AVP (8, 21), but the magnitude of these responses are modest and the degree of hypernatremia is mild when compared with these other models. Moreover, the level of pNa+ measured after the acute administration of 2.0 M NaCl is well below the range (>165 meq/L) that is found to increase concentrations of brain osmolytes, which is an adaptive response that buffers the central nervous system (CNS) against critical deviations in osmolality that occur with severe hypernatremia (23). Taken together, the results suggest that the paradigm used in our studies produces a relatively mild hypernatremia that elicits commensurate water intake and systemic AVP release.

During hypernatremia, augmented sympathetic nervous system activity (6), elevated systemic AVP (8), and suppressed synthesis of angiotensin-II (9) promote renal water reabsorption and sodium excretion, thereby buffering against the increased pNa+. These compensatory responses prevent inordinate deviations in the pNa+; however, hydromineral balance can be restored only by osmotic thirst and consequent increased water consumption. Given that thirst alleviates hypernatremia, it is possible that this mildly aversive stimulus alters the perception of restraint stress or anxiety testing. Considering the impact of another dipsogenic stimulus on stress responsiveness and mood provides insight on the specificity of the observed effects.

Blood loss or decreased blood pressure elicits volemic thirst by increasing circulating levels of angiotensin-II, which activates angiotensin type-1 receptors in the subfornical organ to promote water intake (21, 25, 26). When matched for dipsogenic potency, volemic and osmotic thirst activates the HPA axis with different efficacies (21). Relative to the robust HPA activation that follows hypotension-evoked thirst, the increases in ACTH and CORT subsequent to acute hypernatremia are modest (21). Moreover, stimuli that increase circulating angiotensin-II are known to be anxiogenic (20, 27), but the present results, in conjunction with our previous studies, suggest that mild increases in the pNa+ have the opposite effect (9). Although it is possible that the thirst that arises from acute mild hypernatremia may alter the perception of temporally contiguous stressors, this effect does not generalize to angiotensin-II, another potently acting stimulus for water intake. An alternative interpretation is that the anxiolytic effects of acute mild hypernatremia may facilitate the restoration of hydromineral balance by buffering the impact of stressors that may be encountered during water-seeking and -drinking behavior.

As mentioned, increased pOsm is sensed by the brain, which promotes water intake and AVP secretion to alleviate elevated plasma tonicity. Although these compensatory responses to osmotic dehydration are well characterized, the molecular identity of the central osmosensor is an active area of research. For the most part, the CNS is buffered from changes in plasma tonicity, but the exceptions are the circumventricular organs and vascularized brain nuclei with an incomplete blood-brain barrier. In particular, the OVLT is a circumventricular organ that is thought to be the seat of osmosensing because a lesion of this nucleus decreases the water intake and AVP release that follows hypernatremia (28, 29). Investigation of the mechanism underlying osmosensing has focused on ion channels that are gated by changes in osmolality. Specifically, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 receptors (TRPV1) are cation channels that have been implicated in osmosensing because mice lacking TRPV1 have attenuated thirst and AVP release after hyperosmolality (30, 31). Additionally, the increased action potential discharge of OVLT neurons that occurs in wild-type mice was absent in TRPV1 knockout mice (30). However, others have found that TRPV1 knockouts exhibit normal water intake induced by hypernatremia (32), and modification of the TRPV1 genetic locus to generate mice that accurately report the TRPV1 expression fail to demonstrate the presence of these channels in brain nuclei implicated in osmosensing (33). Regardless of the molecular identity of the osmosensor, it is clear that hypernatremia activates neurons in the dorsal cap of the OVLT (34), and this is consistent with the increased Fos induction that we observed in this nucleus subsequent to 2.0 M NaCl administration.

Although it is established that increased plasma osmolality triggers renal water reabsorption by causing the activation of AVP-containing neurons in the SON and PVN, less well known is the excitatory influence that hypernatremia has on OT neurons within these nuclei. That is, increased plasma osmolality also stimulates osmosensing neurons in the OVLT that activate OT-containing neurons in the SON and PVN, and this is consistent with the strong Fos induction that is found within OT neurons after the administration of 2.0 M NaCl (9, 35, 36). The firing of OT neurons increases the circulating levels of OT, which alleviates hypernatremia by causing natriuresis (7, 35). Systemic levels of OT increase minutes after the onset of hypernatremia (8); however, subsequent to systemic release, central OT increases approximately 300% above baseline levels and reaches concentrations 10-fold higher than those in plasma (10–12). Moreover, the increased brain OT that follows hypernatremia is maintained for more than 2.5 hours, and it is during this time that animals were exposed to psychogenic stressors in the present study (10–12).

Recently the actions of OT within the CNS have been investigated as a potential therapeutic treatment for affective disorders (3–5). Several affective disorders are associated with impaired stress responsiveness that is assessed, in part, by the activity of the HPA axis. The activation of the HPA axis is initiated by the firing of CRH expressing neurons in the PVN and is finalized by the secretion of CORT from the adrenal gland, and both are known to be dysregulated with psychopathology (37). As mentioned earlier, the rats rendered mildly hypernatremic had CORT responses that were attenuated relative to normonatremic controls, and this replicates the results from our prior study (9). Hypernatremia greatly elevates the central levels of OT (10–12), and OT is known to influence activity of the HPA axis. In this regard, central administration of OT attenuates stress-induced elevations in CORT (38), and the genetic deletion of OT has the opposite effect (39). Collectively, these results suggest that the acute elevations in pNa+ stimulate central OT release, which inhibits the activation of the HPA axis that follows stress exposure.

Our study did not directly test whether the blunted HPA response and attenuated anxiety-like behavior that follow the administration of 2.0 M NaCl is mediated by increased central OT, and additional experiments are required to establish causality. However, the results from our electrophysiological experiments revealed that acute hypernatremia promotes an inhibitory oxytocinergic tone on parvocellular neurosecretory neurons within the PVN. Specifically, electrophysiological recordings obtained from brain slices taken from rats previously administered 2.0 M NaCl found that significantly more current was required to hold the cell at −70 mV subsequent to application of the OT receptor antagonist, an effect that was largely absent in the 0.15 M NaCl-treated controls. Although additional experiments are required to determine the cellular and synaptic mechanisms through which OT exerts this inhibitory tone on parvocellular neurosecretory neurons, speculation about the location of OT receptors mediating this effect may provide insight. Firing of parvocellular neurosecretory neurons leads to the release of CRH and other neuropeptides into the median eminence to activate the HPA axis. Oxytocin receptors are expressed on CRH neurons (40), and hypernatremia may trigger the dendritic release of OT, which, through a paracrine mechanism, activates these OT receptors to elicit hyperpolarization of parvocellular neurosecretory neurons, thereby suppressing HPA activity. Alternatively, the activation of OT receptors depolarizes γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurons (41, 42), and the elevated central OT that follows acute hypernatremia may inhibit parvocellular neurosecretory neurons by acting on OT receptors located on γ-aminobutyric acid expressing (GABAergic) neurons.

In addition to its effects on the HPA axis, acute hypernatremia increased restraint-induced Fos induction within discrete regions of the lateral septum (LS), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), and amygdala (AMYG) relative to normonatremic controls. The LS, BNST, and AMYG are densely interconnected and comprise a neuronal network that is heavily implicated in the control of stress-responsiveness and anxiety-like behavior (43–46). Behavioral models of anxiety elicit Fos expression in the LS, BNST, and AMYG (47, 48), and we used the EPM to determine whether the increased Fos that was observed in hypernatremic rats was predictive of altered anxiety-like behavior. Rats delivered 2.0 M NaCl spent more time in the open arms of the EPM but traveled less distance relative to controls, suggesting that acute hypernatremia is anxiolytic. The increased open arm time and decreased locomotor activity that followed acute hypernatremia is reminiscent of the anxiolytic and slight sedative effects of benzodiazepines, which activate GABA-A receptors (49). GABA-A receptors are expressed in the LS, BNST, and AMYG, and the selective deletion of these receptors from CRH neurons increases anxiety-like behavior (50, 51). Interestingly, the LS, BNST, and AMYG receive OT afferents, and the axonal release of OT is found to decrease conditioned fear by activating the GABAergic neurons in the AMYG (41). Because hypernatremia elevates the central levels of OT, it is possible that the increased Fos in the LVS, BNSToc, and CeL is the result of OT-induced activation of the GABAergic neurons in these nuclei. Thus, the elevated pNa+ may trigger the release of oxytocin from the axons terminating in the LVS, BNSToc, and CeL, which activates the GABAergic neurons, which, in turn, promote an anxiolytic mood by inhibiting the CRH neurons.

Although anxiety disorders are more prevalent in females (52), we chose to conduct our studies using male subjects. Ovarian hormones mediate central OT receptor signaling to influence a variety of behavioral and physiological processes including reproduction (53), maternal care (54), and lactation (55). In contrast, relatively few stimuli consistently increase endogenous OT levels in males, and consequently, the present research was conducted to evaluate the utility of acute hypernatremia as such a stimulus. Ovarian hormones are also known to influence body fluid homeostasis (56), and acute hypernatremia may affect females differently from males. Subsequent studies using female subjects are required to determine whether the stress-attenuating effects of acute hypernatremia occur in both sexes.

In summary, mild elevations in pNa+ were found to produce an inhibitory oxytocinergic tone on neurosecretory neurons in the PVN, which may contribute to the decreased CORT that is observed when hypernatremic rats undergo restraint. Moreover, the inhibitory tone and decreased CORT that accompanied acute hypernatremia was associated with increased activation in the subregions of the LS, BNST, and AMYG, and this was predictive of decreased anxiety-like behavior in the EPM. We propose that mild hypernatremia promotes anxiolytic mood by elevating central OT levels, which activates GABA neurons but inhibits CRH neurons in brain nuclei controlling stress responsiveness and anxiety-like behavior.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL096830 (to E.G.K.) and HL083810 (to A.D.d.K.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AMYG

- amygdala

- AVP

- arginine vasopressin

- BNST

- bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

- BNSToc

- oval capsule of the BNST

- BNSTvl

- ventral-lateral BNST

- CeL

- central nucleus of the amygdala

- CeM

- central nucleus of the amygdala

- CNS

- central nervous system

- CORT

- corticosterone

- DMH

- dorsal-medial hypothalamus

- EPM

- elevated plus maze

- GABA

- γ-aminobutyric acid

- GABAergic

- GABA expressing

- HPA

- hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- IL

- infralimbic cortex

- KPBS

- potassium PBS

- LS

- lateral septum

- LVS

- lateral septal nucleus

- OT

- oxytocin

- OVLT

- organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis

- P

- postnatal day

- pNa+

- plasma sodium concentration

- pOsm

- plasma osmolality

- PrL

- prelimbic cortex

- PVN

- paraventricular nucleus

- ROI

- region of interest

- SON

- supraoptic nucleus

- TRPV1

- transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 receptor.

References

- 1. Kessler R, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Walters E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang P, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus H, Wells K, Kessler R. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States—results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neumann ID, Landgraf R. Balance of brain oxytocin and vasopressin: implications for anxiety, depression, and social behaviors. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:649–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lin EJ. Neuropeptides as therapeutic targets in anxiety disorders. Curr Pharmaceut Des. 2012;18(35):5709–5727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Modi ME, Young LJ. The oxytocin system in drug discovery for autism: animal models and novel therapeutic strategies. Horm Behav. 2012;61:340–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stocker SD, Osborn JL, Carmichael SP. Forebrain osmotic regulation of the sympathetic nervous system. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Verbalis JG, Mangione MP, Stricker EM. Oxytocin produces natriuresis in rats at physiological plasma concentrations. Endocrinology. 1991;128:1317–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Interaction of osmotic and volume stimuli in regulation of neurohypophyseal secretion in rats. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:R267–R275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krause EG, de Kloet AD, Flak JN, et al. Hydration state controls stress responsiveness and social behavior. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5470–5476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ludwig M, Horn T, Callahan MF, Grosche A, Morris M, Landgraf R. Osmotic stimulation of the supraoptic nucleus: central and peripheral vasopressin release and blood pressure. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:E351–E356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ludwig M, Sabatier N, Dayanithi G, Russell JA, Leng G. The active role of dendrites in the regulation of magnocellular neurosecretory cell behavior. Progr Brain Res. 2002;139:247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ludwig M, Leng G. Dendritic peptide release and peptide-dependent behaviours. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:126–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ben-Barak Y, Russell JT, Whitnall MH, Ozato K, Gainer H. Neurophysin in the hypothalamo-neurohypophysial system. I. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies. J Neurosci. 1985;5:81–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 6th ed London: Academic Press, Elsevier; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tasker JG, Dudek F. Electrophysiological properties of neurones in the region of the paraventricular nucleus in slices of rat hypothalamus. J Physiol. 1991;434:271–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Luther J, Tasker JG. Voltage-gated currents distinguish parvocellular from magnocellular neurones in the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Physiol. 2000;523(Pt 1):193–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Luther J, Daftary S, Boudaba C, Gould G, Halmos K, Tasker JG. Neurosecretory and non-neurosecretory parvocellular neurones of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus express distinct electrophysiological properties. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14:929–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stern J. Electrophysiological and morphological properties of pre-autonomic neurones in the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Physiol. 2001;537:161–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee S, Han T, Sonner P, Stern J, Ryu P, Lee S. Molecular characterization of T-type Ca(2+) channels responsible for low threshold spikes in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus neurons. Neuroscience. 2008;155:1195–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krause EG, de Kloet AD, Scott KA, et al. Blood-borne angiotensin II acts in the brain to influence behavioral and endocrine responses to psychogenic stress. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15009–15015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krause EG, Melhorn SJ, Davis JF, et al. Angiotensin type 1 receptors in the subfornical organ mediate the drinking and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to systemic isoproterenol. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6416–6424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dunn FL, Brennan TJ, Nelson AE, Robertson GL. The role of blood osmolality and volume in regulating vasopressin secretion in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:3212–3219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heilig CW, Stromski ME, Blumenfeld JD, Lee JP, Gullans SR. Characterization of the major brain osmolytes that accumulate in salt-loaded rats. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:F1108–F1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Imaki T, Vale W, Sawchenko PE. Regulation of corticotropin-releasing factor mRNA in neuroendocrine and autonomic neurons by osmotic stimulation and volume loading. Neuroendocrinology. 1992;56:633–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fitts DA. Angiotensin II receptors in SFO but not in OVLT mediate isoproterenol-induced thirst. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:R7–R15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Simpson JB, Epstein AN, Camardo JS., Jr Localization of receptors for the dipsogenic action of angiotensin II in the subfornical organ of rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1978;92:581–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leshem M. Low dietary sodium is anxiogenic in rats. Physiol Behav. 2011;103:453–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thrasher TN, Keil LC. Regulation of drinking and vasopressin secretion: role of organum vasculosum laminae terminalis. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:R108–R120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McKinley MJ, McAllen RM, Davern P, et al. The sensory circumventricular organs of the mammalian brain. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2003;172:III–XII, 1–122, back cover [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ciura S, Bourque CW. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 is required for intrinsic osmoreception in organum vasculosum lamina terminalis neurons and for normal thirst responses to systemic hyperosmolality. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9069–9075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sharif Naeini R, Witty MF, Séguéla P, Bourque CW. An N-terminal variant of Trpv1 channel is required for osmosensory transduction. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taylor AC, McCarthy JJ, Stocker SD. Mice lacking the transient receptor vanilloid potential 1 channel display normal thirst responses and central Fos activation to hypernatremia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1285–R1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cavanaugh DJ, Chesler AT, Jackson AC, et al. Trpv1 reporter mice reveal highly restricted brain distribution and functional expression in arteriolar smooth muscle cells. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5067–5077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bisley JW, Rees SM, McKinley MJ, Hards DK, Oldfield BJ. Identification of osmoresponsive neurons in the forebrain of the rat: a Fos study at the ultrastructural level. Brain Res. 1996;720:25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Negoro H, Higuchi T, Tadokoro Y, Honda K. Osmoreceptor mechanism for oxytocin release in the rat. Jpn J Physiol. 1988;38:19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rinaman L, Stricker EM, Hoffman GE, Verbalis JG. Central c-Fos expression in neonatal and adult rats after subcutaneous injection of hypertonic saline. Neuroscience. 1997;79:1165–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Holsboer F, Barden N. Antidepressants and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical regulation. Endocr Rev. 1996;17:187–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Windle RJ, Kershaw YM, Shanks N, Wood SA, Lightman SL, Ingram CD. Oxytocin attenuates stress-induced c-fos mRNA expression in specific forebrain regions associated with modulation of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal activity. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2974–2982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mantella RC, Vollmer RR, Amico JA. Corticosterone release is heightened in food or water deprived oxytocin deficient male mice. Brain Res. 2005;1058:56–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dabrowska J, Hazra R, Ahern TH, et al. Neuroanatomical evidence for reciprocal regulation of the corticotrophin-releasing factor and oxytocin systems in the hypothalamus and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of the rat: implications for balancing stress and affect. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:1312–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Knobloch HS, Charlet A, Hoffmann LC, et al. Evoked axonal oxytocin release in the central amygdala attenuates fear response. Neuron. 2012;73:553–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huber D, Veinante P, Stoop R. Vasopressin and oxytocin excite distinct neuronal populations in the central amygdala. Science. 2005;308:245–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sheehan TP, Chambers RA, Russell DS. Regulation of affect by the lateral septum: implications for neuropsychiatry. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;46:71–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Volz HP, Rehbein G, Triepel J, Knuepfer MM, Stumpf H, Stock G. Afferent connections of the nucleus centralis amygdalae. A horseradish peroxidase study and literature survey. Anat Embryol. 1990;181:177–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Risold PY, Swanson LW. Chemoarchitecture of the rat lateral septal nucleus. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;24:91–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Risold PY, Swanson LW. Connections of the rat lateral septal complex. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;24:115–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Duncan GE, Knapp DJ, Breese GR. Neuroanatomical characterization of Fos induction in rat behavioral models of anxiety. Brain Res. 1996;713:79–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nguyen NK, Keck ME, Hetzenauer A, et al. Conditional CRF receptor 1 knockout mice show altered neuronal activation pattern to mild anxiogenic challenge. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188:374–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Belzung C, Misslin R, Vogel E. Behavioural effects of the benzodiazepine receptor partial agonist RO 16-6028 in mice. Psychopharmacology. 1989;97:388–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hechler V, Gobaille S, Maitre M. Selective distribution pattern of γ-hydroxybutyrate receptors in the rat forebrain and midbrain as revealed by quantitative autoradiography. Brain Res. 1992;572:345–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gafford GM, Guo JD, Flandreau EI, Hazra R, Rainnie DG, Ressler KJ. Cell-type specific deletion of GABA(A)α1 in corticotropin-releasing factor-containing neurons enhances anxiety and disrupts fear extinction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:16330–16335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pigott TA. Anxiety disorders in women. Psychiatric Clin North Am. 2003;26:621–672, vi–vii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Arletti R, Bertolini A. Oxytocin stimulates lordosis behavior in female rats. Neuropeptides. 1985;6:247–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bosch OJ, Neumann ID. Both oxytocin and vasopressin are mediators of maternal care and aggression in rodents: from central release to sites of action. Horm Behav. 2012;61:293–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Neumann ID. Stimuli and consequences of dendritic release of oxytocin within the brain. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1252–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Curtis KS. Estrogen and the central control of body fluid balance. Physiol Behav. 2009;97:180–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]