Abstract

Neuronal plasticity is regulated by the ovarian steroids estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4) in many normal brain functions, as well as in acute response to injury and chronic neurodegenerative disease. In a female rat model of axotomy, the E2-dependent compensatory neuronal sprouting is antagonized by P4. To resolve complex glial-neuronal cell interactions, we used the “wounding-in-a-dish” model of neurons cocultured with astrocytes or mixed glia (microglia to astrocytes, 1:3). Although both astrocytes and mixed glia supported E2-enhanced neurite outgrowth, P4 antagonized E2-induced neurite outgrowth only with mixed glia, but not astrocytes alone. We now show that P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth is mediated by microglial expression of progesterone receptor (Pgr) membrane component 1 (Pgrmc1)/S2R, a putative nonclassical Pgr mediator with multiple functions. The P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth was restored by add-back of microglia to astrocyte-neuron cocultures. Because microglia do not express the classical Pgr, we examined the role of Pgrmc1, which is expressed in microglia in vitro and in vivo. Knockdown by siRNA-Pgrmc1 in microglia before add-back to astrocyte-neuron cocultures suppressed the P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth. Conditioned media from microglia restored the P4-E2 activity, but only if microglia were activated by lipopolysaccharide or by wounding. Moreover, the microglial activation was blocked by Pgmrc1-siRNA knockdown. These findings explain why nonwounded cultures without microglial activation lack P4 antagonism of E2-induced neurite outgrowth. We suggest that microglial activation may influence brain responses to exogenous P4, which is a prospective therapy in traumatic brain injury.

Cross talk between estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4) operates throughout the female reproductive system in cycles of E2-dependent cell growth and P4-dependent cell regression. However, little is known of the brain cell interactions that enable “P4-E2 antagonism” in synaptic plasticity. In neuronal responses to injury that involve P4-E2 antagonism, we describe a novel role of microglial activation that is mediated by progesterone receptor (Pgr) membrane component 1 (Pgrmc1)/S2R, a nonclassical Pgr of emerging significance to brain neuronal functions and innate immunity.

In the hippocampus, synaptic remodeling during the rat estrous cycle is driven by serial elevations of E2 and P4 (1). Neuronal sprouting in response to axotomy is also modulated by P4-E2 antagonism. In an adult rat model of entorhinal cortex lesions that axotomize the perforant pathway to the hippocampus, the ensuing compensatory neurite outgrowth into the dentate gyrus molecular layer was stimulated by E2 and blocked by concurrent administration of E2+P4 (2). Astrocyte and microglial activation in the deafferented zone was correspondingly modulated by E2 and P4. An unexpected role of microglia in P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth was identified with the “wounding-in-a-dish” model of axotomy, in which cocultures of cerebral cortex neurons and glia from the neonatal rat are given scratch wounds, with ensuing E2-dependent neurite outgrowth (3). The P4 antagonism of E2-dependent neurite outgrowth was blocked by the drugs ORG-31710 and RU-486, which have specificity for Pgr, the classical DNA-binding Pgr. However, the P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth was observed only in coculture with mixed glia (1:3 microglia to astrocytes), but not in enriched astrocytes from which microglia were removed (2). This result was puzzling because Pgr was not detected in microglia (4). We were also concerned about possible artifacts induced by the removal of microglia from mixed glia by a standard protocol of mechanical shaking for 4 hours (5), because hydrodynamic forces can alter gene expression in astrocytes (6) and endothelial cells (7).

To further evaluate the role of microglia and to define the Pgrs involved, we developed a protocol to reconstitute mixed glia by “microglial add-back” to enriched astrocyte cultures. We investigated the role of a putative nonclassical Pgr, known as Pgrmc1/S2R among other names, which has diverse activities in many cell types (8–11). Pgrmc1, a 22-25 kDa protein initially described in liver (9, 12), with a sequence unrelated to Pgr or to the large family of progestin/adipoQ membrane receptors. The activities of Pgrmc1 in brain cells include mediation of the P4-dependent proliferation of rat neural stem cells (13), the rapid P4 inhibition of calcium oscillations in hypothalamic GnRH neurons (14), and the P4 antagonism of epithelial cell ion channels (15). In hippocampal neurons, Pgrmc1 is induced by both E2 and P4 (16, 17). During development of nematode and mouse, it regulates neurite outgrowth, under the names VEM-1 and vema, respectively (18, 19). Named also as 25-Dx, it is induced by brain injury in neurons and astrocytes (20). Lastly, under the name σ-2 receptor (alternatively Pgrmc1/S2R), it influences the motility of microglia (21) and cancer invasiveness without exogenous P4 (11). For simplicity, this text refers to Pgrmc1. Despite an initial designation as a “progesterone receptor membrane component” and its role in neuron membrane calcium flux (15), Pgrmc1 also occurs in the nucleus of several cell types (9, 22). The following in vitro experiments show that Pgrmc1 in activated microglia mediates the P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth in the wounding-in-a-dish model and that the activation of microglia also depends on Pgrmc1.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and wounding-in-a-dish coculture

All experiments conformed to standards of humane animal care in the National Institutes of Health Ethical Guidelines and were approved by University of Southern California's Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee. Primary mixed glia cultures from cerebral cortices of 3- to 4-day-old rat pups (Sprague Dawley) were maintained in DMEM/F12 media (Cellgro, Manassas, Virginia), supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (P4 < 0.10 ng/mL; E2 < 0.10 pg/mL; HyClone Laboratories, Logan, Utah), 100 U/mL penicillin, 50 U/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine at 37°C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity. Primary neurons from embryonic day 18 (E18) rat cortices were maintained in high-glucose DMEM (Cellgro), supplemented with B27 supplement without antioxidants and P4, 2.4 mg/mL BSA, 0.1 mM sodium pyruvate, 15 mM HEPES, 200 U/ml penicillin, and 100 U/ml streptomycin. Microglia were separated from astrocytes in 2-week-old confluent mixed glia cultures by shaking 4 hours (5). Cell cultures were characterized by immunocytochemistry (ICC) using cell-specific markers for astrocytes glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and microglia (IBA1 and CD11b). Primary cultures of mixed glia contain microglia and astrocytes (dilution 1:3), whereas enriched astrocyte and microglia cultures are 95% monotypic (2). Enriched astrocyte, enriched microglia, or mixed glia cultures were plated in poly-d-lysine-coated 4-chamber glass slides (Nunc Lab-Tek II Chamber Slide System; Thermo Scientific, Rochester, New York) at 2 × 105 cells per well for mixed glia. Microglia and astrocytes were plated at 1:3 (microglia, 0.6 × 105 cells per well; astrocytes, 1.4 × 105 cells per well). For microglia and astrocyte add-back, pilot experiments optimized cell settling and adherence time at 6 hours, when more than 85% cells have attached to the culture slides. For Pgrmc1 small interfering (siRNA) experiments, mixed glia, enriched astrocytes, or enriched microglia were treated with either scrambled siRNA (Silencer Negative Control No. 1 siRNA, AM4611; Ambion, Austin, Texas) or Pgrmc1 siRNA (siRNA ID 253163, nucleotides 977-994). Scrambled and Pgrmc1 siRNAs were mixed with siPORT NeoFX transfection agent (Ambion) to a final concentration of 50 nM, with siRNA transfection according to manufacturer's protocol. Glia were cultured 2 days, followed by plating E18 neurons (7 × 104 cells per well). Glial media with siRNA were removed and cells rinsed with HBSS before plating neurons. For add-back experiments, E18 neurons were plated 6 hours after the add-back of either microglia or astrocytes. The cocultures were grown for 3 days before scratch wounding (2). Scratch wounding employed a grid-template with intersecting lines of 1 cm each that were inscribed with a plastic pipette tip (1 mm diameter), yielding 2 traces per well, which induced consistent cell responses across experiments (2). Immediately after scratch wounding, steroids were added: E2 (0.1 nM, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri) +/− P4 (100 nM, Steraloids, Newport, Rhode Island) in neuronal media, supplemented with B27 supplement without antioxidants or P4. Vehicle control was 0.08% ethanol. For the nonwounding study (see Figure 7), mixed glia-neuron cocultures were treated with steroids in fresh neuronal media supplemented with B27 supplement without antioxidants and P4. Because our focus was on the P4 antagonism of E2 effects, we did not include P4 alone, which was evaluated in prior studies (2). Slides were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde after 2 days for ICC.

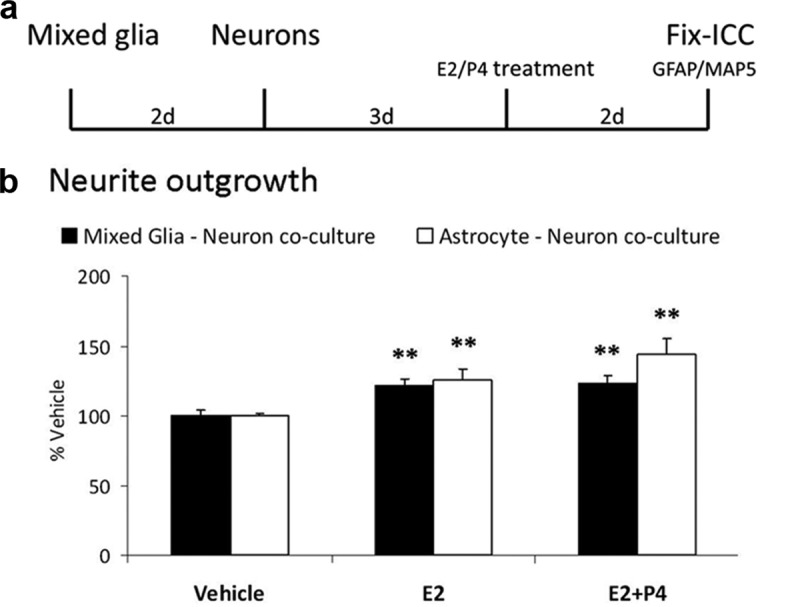

Figure 7.

Nonwounded Mixed Glia-Neuron Cocultures: Absence of P4–E2 Antagonism of Neurite Outgrowth. a, Experimental design: Mixed glia or astrocytes alone were plated in 4-chamber slides, followed by neurons 2 days later. After 3 days, cocultures were treated with either Veh, E2 (0.1 nM), or E2+P4 (E2 0.1 nM; P4 100 nM) for 2 days. Slides were immunostained for microtubule-associated protein (MAP)5 and GFAP. b, E2 increased neurite outgrowth in coculture with astrocytes and mixed glia by 20% (total neurite length; P < .01). P4 did not antagonize E2-induced neurite outgrowth in mixed glia, in contrast to Figure 1. **, P < .01.

Immunocytochemistry and data analysis

After fixing, slides were permeabilized in 1% Noniodet P-40, followed by blocking in 5% normal serum. Slides were incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: mouse monoclonal anti-GFAP (1:400, G3893, Sigma-Aldrich); rabbit polyclonal anti-βIII tubulin (1:1000, T8578, Sigma-Aldrich); mouse monoclonal anti-CD11b (1:200, MCA275G, AbDSerotec, Raleigh, North Carolina); and rabbit polyclonal anti-Pgrmc1 (1:300, HPA002877, Sigma-Aldrich). Secondary antibody incubation was 1 hour at 22°C: goat antimouse Alexa Fluor 488 and goat antirabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (1:500, Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California). CD11b and Pgrmc1 protein were quantified from fluorescent images using ImageJ (NIH software). Data represent average integrated density per cell; 20-30 images per treatment were analyzed; total integrated density per image was normalized to the number of cells per image.

Neurite outgrowth analysis

Images of fluorescence from GFAP and βIII-tubulin-stained slides were captured using a Nikon Eclipse EC300 microscope (Nikon, Melville, New York) in a 1 mm2 area adjacent to the wound tract, 8 random images per wound, 2 wounds per well, total 16 images per well (n = 4 wells per treatment). Neurite outgrowth was quantified by manually counting the number of βIII-tubulin-stained neurites extending into the wound zone, calculated as average neurites/mm2, and expressed as percent (%) vehicle. Our prior studies showed similar E2-P4 effects on both neurite number and neurite length after wounding (2). Lengths of individual neurites extending into the wound zone were calculated from manual tracings by NeuronJ (Image J, NIH software). Total neurite outgrowth in nonwounding experiments was quantified using skeletonized images in NeuronJ (Image J, NIH software). Data represent the sum of all neurites per image (20 images per well; 4 wells per treatment).

Western blotting

Protein lysates from mixed glia, enriched astrocytes, and enriched microglia were homogenized in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 1 mM Na2EDTA; 1 mM EGTA; 1% Nonidet P-40; 1% sodium deoxycholate; 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate; 1 mM β-glycerophosphate; 1 mM Na3VO4; 1 μg/mL leupeptin), containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor. Protein lysates were stored at −80°C until use. Total protein (Pgrmc1, 10 μg) and 25 μg total protein (Pgr) were electrophoresed on 4%-12% Novex NuPage Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen), followed by transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California) for 1 hour at 22°C, followed by incubation in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: rabbit polyclonal anti-Pgrmc1 (1:1000, HPA002877, Sigma-Aldrich) and rabbit polyclonal anti-Pgr (1:500, sc-538; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California). Secondary antibody incubation was 1 hour at 22°C with goat antirabbit-horseradish peroxidase (1:4000, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pennsylvania). Signal was developed using SuperSignal West Pico ECL Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Pgr antibody specificity was validated by preabsorption with 10-fold excess of Pgr blocking peptide (sc-538P, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), which eliminated the 2 bands for the 2 isoforms (∼95 kDa, PgrA; ∼110 kDa, Pgr B) and their immunocytochemical signal (16). The specificity of the Pgrmc1 antibody was verified by Western blots (16).

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was isolated from mixed glia, enriched astrocyte, or enriched microglia from 4 culture preparations. cDNA was prepared from total cellular RNA (Super Script III; Invitrogen) and RT-PCR was performed on an Opticon 2 (Bio-Rad) with primers below.

Pgr-forward (F), GTCAGTGGACAGATGCTA, Pgr-reverse (R), AGCTGTTTCACAAGATCA

Pgrmc1-F, CTGCCGAACTAAGGCGATAC, Pgrmc1-R, TCCCAGTCATTCAGGGTCTC

Actin-F, CTGGCACCACACCTTCTACAATG; Actin-R, GAAATCGTGCGTGACATCAAAGAG

Statistical analysis

Data are ± SEM, average of 3 experiments. Neurite outgrowth data is % vehicle, except for neurite length data in Figure 2. Statistical comparisons used raw data, based on ANOVA followed by Fisher post hoc analysis, significance at P < .05. The un-normalized data on neurite numbers and outgrowth with full statistics are in Supplemental Table 1 published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org.

Figure 2.

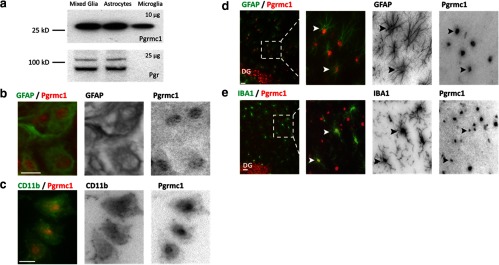

Glial Expression of Pgrmc1 and Pgr. a, Western blots with 10 μg total protein from mixed glia, astrocytes, or microglia alone showed Pgrmc1 in both astrocytes and in microglia. No Pgr was detected in microglia with 25 μg total protein. b and c, Pgrmc1 protein in cultured primary astrocytes and microglia by ICC. Double ICC for GFAP and Pgrmc1 detected Pgrmc1 in astrocytes (b). Double ICC using CD11b and Pgrmc1 detected Pgrmc1 in microglia (c). Scale bars, 20 μm. d and e, Pgrmc1 protein in the rat hippocampus dentate gyrus (DG) molecular layer. Double IHC using GFAP and Pgrmc1 detected Pgrmc1 in astrocytes (d). Double IHC using IBA1 and Pgrmc1 detected Pgrmc1 in microglia in vivo (e). Scale bars, 20 μm.

Results

Microglial requirement for P4 antagonism of neurite outgrowth

Prior studies with the wounding-in-a-dish model developed the hypothesis that microglia were critical mediators of P4-E2 antagonism of postaxotomy neurite outgrowth observed in mixed glia-neuron cocultures: the antagonism was absent from enriched astrocytes from which microglia had been removed by shaking (2). To evaluate the requirement of microglia in P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth, microglia were added back to plated astrocytes according to a protocol that optimized settling and adherence, followed by neuronal overlay and wounding of the reconstituted mixed glial cocultures (Figure 1a).

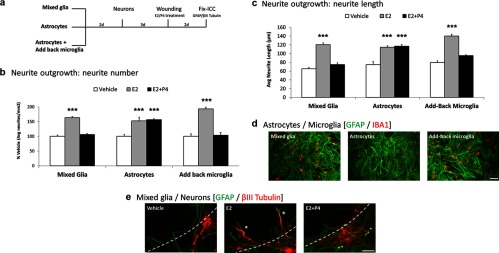

Figure 1.

Microglial Requirement for P4 Antagonism of Neurite Outgrowth. a, Mixed glia or astrocytes alone, or astrocytes with microglia added-back (reconstituted mixed glia) were plated in 4-chamber slides, followed by neurons 2 days later. After 3 days, cocultures were scratch wounded on a defined grid (Materials and Methods). Immediately after wounding, cocultures were treated with either vehicle (Veh), E2 (0.1 nM), or E2+P4 (E2 0.1 nM; P4 100 nM) for 2 days. Slides were immunostained for βIII-tubulin (neuron) and GFAP (astrocyte). Neurite outgrowth was quantified by the number and length of βIII-tubulin immunostained neurites extending into the wound zone. b, In mixed glia-neuron cocultures, E2 increased neurite outgrowth (average neurite number) 63% (P < .0001) and P4 antagonized the E2-induced neurite outgrowth (average neurite number: Veh, 5.2 ± 0.5; E2 9.5 ± 0.8; E2+P4 5.0 ± 0.6; P < .001). In astrocyte-neuron cocultures, E2 increased neurite outgrowth (P < .001), but absent microglia, P4 did not antagonize E2-induced neurite outgrowth (P < .001) (neurite number: Veh, 6.4 ± 0.4; E2 9.8 ± 0.8; E2+P4 10.1 ± 0.2; P < .001). In reconstituted mixed glia (astrocytes with add-back microglia) P4 antagonized E2-induced neurite outgrowth (neurite number: Veh, < 4.3 ± 0.4; E2, 8.3 ± 0.2; E2+P4, 4.5 ± 0.4; P < .0001). c, Neurite length analyses showed similar P4–E2 effects as on neurite numbers (b). In mixed glia, E2 increased the average length of neurites extending into the wound zone 83% (P < .0001) whereas P4 antagonized the E2-induced neurite outgrowth (average neurite length in microns: Veh, 131 ± 5.3; E2, 241 ± 8.2; E2+P4, 150 ± 7.5; P < .0001). P4 did not antagonize neurite length in enriched astrocyte cultures without microglia. E2 induction of average neurite length was similar to neurite number (P < .0001) neurite length in microns: Veh, 149 ± 14.2; E2, 229 ± 6.3; E2+P4, 234 ± 6.3; P < .0001). In add-back microglia cultures, E2 increased neurite length 75% (P < .0001) and P4 antagonized the E2-induced neurite outgrowth (neurite length in microns: Veh, 159 ± 7.4; E2, 280 ± 8.7; E2+P4, 191 ± 3.5; P < .0001). d, Cell composition in cultured mixed glia, enriched astrocytes, and reconstituted mixed glia after add-back microglial add-back; immunostaining of astrocytes for GFAP (green), microglia for IBA1 (red). Microglia-astrocyte: ratios were similar in mixed glia and add-back microglia cultures (1:3); enriched astrocyte cultures had <5% microglia. Scale bars, 50 μm. e, Representative images of wounded mixed glia-neuron cocultures (GFAP green, astrocytes; βIII-tubulin red, neurons) treated with vehicle, E2, or E2+P4. The dotted line shows the wound zone. The E2-induced neurite outgrowth into the wound zone (asterisks) was antagonized by P4. Scale bars, 50 μm. ***, P < .001.

Microglial add-back restored the P4 antagonism of E2-induced neurite outgrowth to astrocyte-neuron cocultures (Figure 1b), consistent with the hypothesis (2) that microglia contribute directly to P4 antagonism of E2-dependent neurite outgrowth. This result also indicates that the shaking procedure to remove microglia did not impair the P4 antagonism of E2-induced neurite outgrowth, which was a possible confound because hydrodynamic forces can alter astrocyte gene expression (6). In the reconstituted mixed glia-neuron cocultures, E2 increased both neurite numbers (Figure 1b) and average neurite length (Figure 1c); again, both showed P4 antagonism (Figure 1, b and c). In both the initial and the reconstituted mixed glia, the total length of neurites extending into the wound zone showed similar increases in response to E2 and similar inhibition by P4 + E2. These findings with microglial add-back extend findings of Wong et al. (2) that mixed glia-neuron and astrocyte-neuron cocultures show similar effects of E2-P4 on neurite numbers and neurite length. The survival of neurons after wounding was not altered by steroid treatments or glial cell composition (Supplemental Table 2).

Pgr expression in astrocytes and microglia

The requirement for microglia in the P4 antagonism of E2-dependent neurite outgrowth was puzzling because of a report that microglia lack the expression of the classical receptor Pgr (4) and because we had shown that 2 Pgr antagonists blocked the P4 antagonism (2). To identify the receptors that may mediate the microglia-mediated P4-E2 antagonism, we characterized the glial expression of Pgr. We also considered Pgrmc1 because of its role in neurite guidance during development (17, 18). Consistent with the report on fluorescence-activated cell sorting-sorted microglia from adult mouse (4), we did not detect Pgr in neonatal rat microglia. Western blots detected Pgr isoforms of the expected size (∼95 kDa, Pgr A; 110 kDa, Pgr B) (23) in extracts of mixed glial and enriched astrocytes, whereas no Pgr signal was detected from microglia (Figure 2a). These findings were confirmed by RT-PCR (Supplemental Table 3). For Pgr, both mixed glia and astrocytes had identical threshold cycle values (∼33), whereas that for microglia was unreliably low (>37). Pgrmc1 was detected in mixed glia, enriched astrocytes, and enriched microglia by Western blots (Figure 2a) and RT-PCR (Supplemental Table 3). The RT-PCR threshold cycle for Pgrmc1 was nearly identical for mixed glia, astrocytes, and microglia (∼23). The expression of Pgrmc1 in both astrocytes and microglia was confirmed by double ICC in vitro (Figure 2, b and c) and in vivo, in the dentate gyrus molecular layer (Figure 2, d and e). The Westerns and ICC suggest microglia have lower prevalence of Pgrmc1. The subcellular localization showed dense immunostaining in cell nuclei of astrocytes and microglia (Figure 2, b–e). Based on these results, we evaluated the glial role of Pgrmc1 in our model.

Microglial Pgrmc1 is required for P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth

Pgrmc1 levels were decreased by siRNA knockdown in mixed glia (1:3, microglia to astrocytes), or in enriched astrocytes and enriched microglia alone before plating of neurons. In mixed glia-neuron cocultures, Pgrmc1 knockdown eliminated the P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth (Figure 3a). The specificity of this effect is shown by the retention of normal E2-induced neurite outgrowth (P < .0001); the scrambled siRNA control for Pgrmc1 knockdown did not alter P4-E2 antagonism.

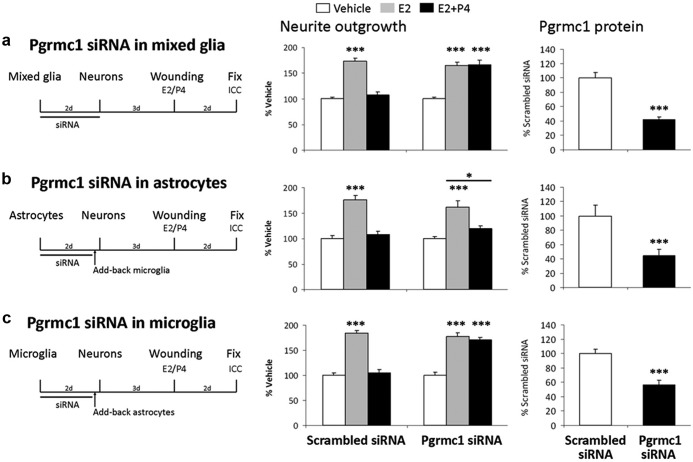

Figure 3.

Requirement of Pgrmc1 in P4 Antagonism of Neurite Outgrowth. a, Pgrmc1 siRNA in mixed glia. Left panel, experimental design: Mixed glia were treated with scrambled siRNA (control) or Pgrmc1 siRNA. Center panel, neurite outgrowth: in scrambled siRNA controls, E2 increased neurite outgrowth 73% (P < .0001) and P4 antagonized E2-induced neurite outgrowth (average neurite number: Veh, 2.2 ± 0.3; E2, 3.7 ± 0.4; E2+P4, 2.4 ± 0.3; P < .01). After Pgrmc1 knockdown, E2 still induced neurite outgrowth 65% (P < .0001), but P4 did not antagonize E2-induced neurite outgrowth (P < .0001) (neurite number: Veh, 2.2 ± 0.2; E2, 3.3 ± 0.3; E2+P4, 3.3 ± 0.3; P < .03). Right panel, Pgrmc1 knockdown analyzed by Western blot showed 58% reduction in Pgrmc1 protein after 48 hours (day 3) (P < .0001). b, Pgrmc1 siRNA in astrocytes only. Astrocytes were treated with siRNA, and untreated microglia were added back. E2 increased neurite outgrowth 75% in scrambled siRNA-treated cocultures (P < .0001). P4 antagonized E2-induced neurite outgrowth (neurite number: Veh, 4.8 ± 0.3; E2, 8.3 ± 0.2; E2+P4, 5.3 ± 0.4; P < .0001). E2 increased neurite outgrowth 61% even with Pgrmc1 knocked down in astrocytes (P < .0001). However, P4 antagonized E2-induced neurite outgrowth (neurite number: Veh, 4.3 ± 0.5; E2, 6.8 ± 0.6; E2+P4, 4.8 ± 0.5; P < .02). Pgrmc1 knockdown in enriched astrocytes caused 55% reduction in Pgrmc1 protein by ICC on day 6 (P < .0001). c, Pgrmc1 knockdown in microglia only with add-back astrocytes. Microglia were treated with siRNA to which untreated astrocytes were added back. In scrambled siRNA controls, E2 increased neurite outgrowth 84% (P < .0001) and P4 antagonized E2-induced neurite outgrowth (neurite number: Veh, 4.1 ± 0.3; E2, 7.6 ± 0.3; E2+P4, 4.4 ± 0.3; P < .0001). Pgrmc1 knockdown in microglia increased E2-dependent neurite outgrowth by 78% (P < .0001) and abolished P4 antagonism of E2-induced neurite (P < .0001) (neurite number: Veh, 3.9 ± 0.3; E2, 7.1 ± 0.4; E2+P4, 6.8 ± 0.3; P < .0001). Pgrmc1 knockdown caused 43% reduction in Pgrmc1 protein at day 6 (P < .0001). ***, P < .001.

Because Pgrmc1 is expressed in both astrocytes and microglia, we evaluated possible independent contributions of astrocytic and microglial Pgrmc1 to P4-E2 antagonism. The Pgrmc1 protein knockdown in astrocytes or microglia persisted at 45% below controls for 5 days (right panel, Figure 3, b and c). After Pgrmc1 knockdown in astrocytes only followed by introduction of untreated microglia, P4 still antagonized E2-induced neurite outgrowth (Figure 3b). Again, E2-induced neurite outgrowth was unimpaired. Thus, astrocytic Pgrmc1 is not required for P4 antagonism of E2-induced neurite outgrowth. In contrast, the add-back of microglia after knockdown of Pgrmc1 to untreated astrocytes abolished the P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth (Figure 3c).

Microglial soluble factors mediate P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth

Microglia could mediate the P4-E2 antagonism directly by cell-to-cell contact, or indirectly through the release of soluble factors in microglial conditioned medium. This question was addressed with conditioned media from enriched microglia, which was added back to astrocyte-neuron cocultures (experimental design, Figure 4a). To identify the simplest experimental conditions for observing microglial activities that enabled P4-E2 antagonism in astrocyte-neuron cocultures, the enriched microglia were plated in glial media with charcoal-stripped FBS that contained minimal steroids at a subconfluent density approximating that of mixed glia.

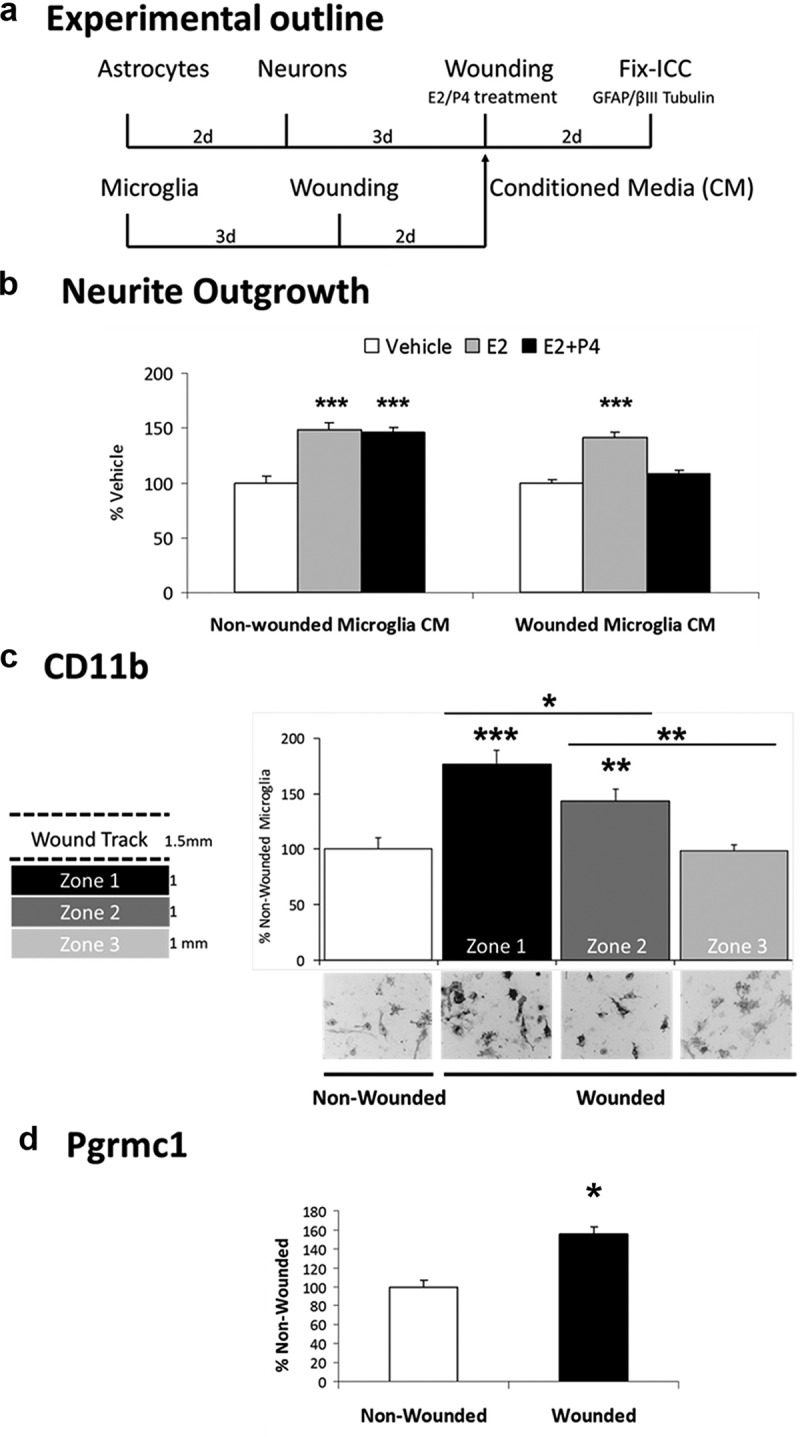

Figure 4.

Requirement of Microglial Wounding for P4 Antagonism of Neurite Outgrowth. a, Experimental design: microglia were grown in 4-chamber slides, followed by scratch wounding. Cell-free conditioned media (CM) from nonwounded or wounded microglia were added to wounded astrocyte-neuron cocultures with vehicle, E2 (0.1 nM), or E2+P4 (E2, 0.1 nM; P4,100 nM). b, With CM from nonwounded microglia, E2 increased neurite outgrowth by 48% (panel b, left) (P < .0001). P4 did not antagonize E2-induced neurite outgrowth measured by length, or by neurite number: Veh, 7.1 ± 0.4; E2, 10.3 ± 0.5; E2+P4, 10.2 ± 0.4; P < .0001). With wounded CM, E2 increased neurite outgrowth by 42% (P < .0001), which was antagonized by P4 measured by length (panel b, right), or by neurite number: Veh, 8.7 ± 0.5; E2, 12.3 ± 0.7; E2+P4, 9.8 ± 0.6; P < .001). c, Microglial CD11b protein levels by ICC in 3 zones of 1 mm width distal to the wound scratch showed progressively decreasing induction: zone 1, 77% increase relative to nonwounded culture (P < .0001); zone 2, 44% increase (P < .03); zone 3, no increase. Micrographs represent cell fields in each zone (scale bar, 50 μm). d, Pgrmc1 induction by scratch wounding, average of zones 1-3, 55% increase vs nonwounded microglia (P < .0001). *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001.

First, we found that add-back of conditioned media from isolated nonwounded microglia did not restore P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth in astrocyte-neuron cocultures (Figure 4b, left). We therefore hypothesized that the E2-P4 antagonism required microglial activation, which we tested by scratch wounding of microglia alone. Conditioned media from scratch-wounded microglia, when added to astrocyte-neuron cocultures, did not alter E2-induced neurite outgrowth but did restore the P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth (Figure 4b, right). The activation of microglia by scratch wounding was evaluated by induction of CD11b, a general marker of microglial activation (24). Scratch wounding induced CD11b with a decreasing gradient extending at least twice the width of the scratch boundary (Figure 4c). Pgrmc1 was also induced in scratch-wounded microglia (Figure 4d).

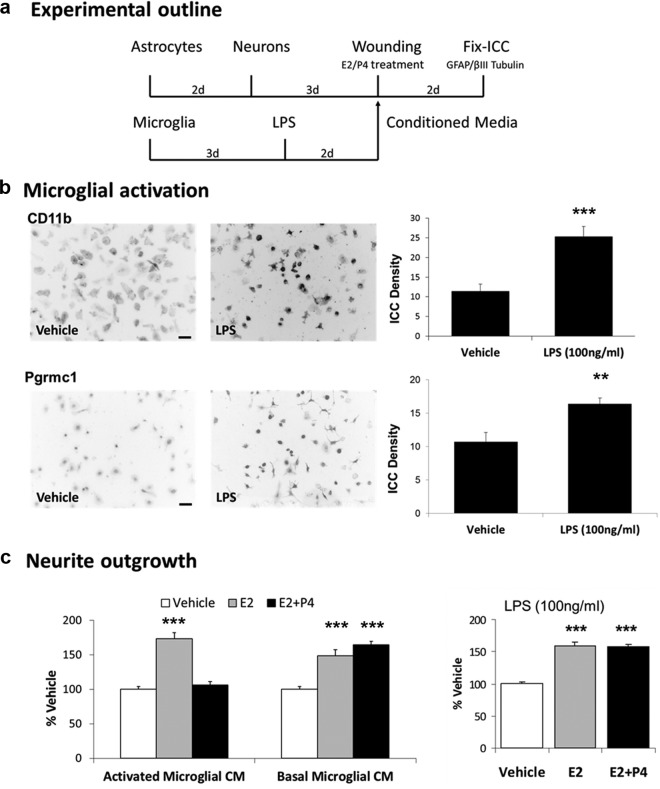

Because scratch wounding is an unconventional model for microglial activation (we have not found a prior report), we also examined conditioned media from microglia activated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) a classic monocyte activator (25) (Figure 5a). Activation by LPS (100 ng/mL) induced microglial CD11b expression 2-fold and also induced Pgrmc1 (Figure 5b). The addition of conditioned media from LPS-activated microglia restored the P4-E2 antagonism to astrocyte-neuron cocultures (Figure 5c, left panel). Controls included conditioned media from microglia without LPS treatment (Figure 5c, middle panel) and addition of LPS to astrocyte-neuron cocultures without microglial conditioned media (Figure 5c, right graph). Thus, microglial activation by 2 distinct modes induces soluble activity (SA) that mediates P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth in the astrocyte-neuron coculture model. Next, we investigated the role of Pgrmc1 in regulating P4-E2 antagonism.

Figure 5.

Requirement of Activated Microglial Secreted Factors for P4 Antagonism of Neurite Outgrowth. a, Microglia were plated in 4-chamber slides and grown for 3 days, followed by treatment with either vehicle or LPS (100 ng/ml) for 2 days. Conditioned media (CM) from unactivated and activated microglia was introduced to wounded astrocyte-neuron cocultures with vehicle, E2 (0.1 nM), or E2+P4 (E2, 0.1 nM; P4, 100 nM). b, CD11b protein in vehicle and LPS-treated microglia by ICC was induced by 122% by LPS (P < .0001). Pgrmc1 protein was also increased by LPS (P < .0001). Mean of 3 individual experiments ± SEM. c (left), In the presence of activated microglial CM, P4 antagonized E2-induced neurite outgrowth (neurite number: Veh, 4.9 ± 0.2; E2, 8.5 ± 0.4; E2+P4, 5.2 ± 0.3; P < .0001). Controls included basal microglial CM that did not support P4 antagonism of E2-induced neurite outgrowth (P < .03) (neurite number: Veh, 5.7 ± 0.5; E2, 8.3 ± 0.3; E2+P4, 9.3 ± 0.6; P < .0001). With LPS-activated microglial CM, E2 increased neurite outgrowth 79% (P < .001). c (right), After treatment of astrocyte-neuron cocultures with LPS alone, E2 increased neurite outgrowth 53% (P < .001). LPS alone had no effect on P4 antagonism: P4 did not antagonize E2-induced neurite outgrowth (P < .001) (neurite number: Veh, 6.1 ± 0.2; E2, 9.9 ± 0.2; E2+P4, 9.6 ± 0.2; P < .0001). **, P < .01; ***, P < .001.

Pgrmc1 mediates P4-E2 antagonism via SA in conditioned media and mediates microglial activation

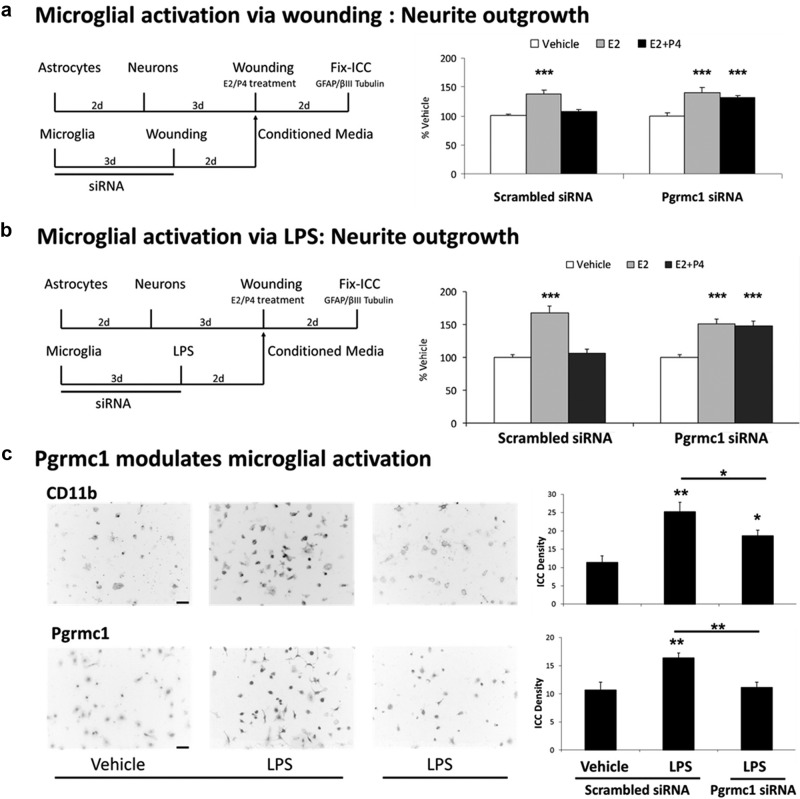

Because Pgrmc1 was induced in LPS-activated microglia, we investigated its role in the conditioned medium SA on neurite outgrowth. Pgrmc1 siRNA knockdown in enriched microglia was followed by microglial activation by scratch wounding in the absence of P4 (Figure 6a). Addition of these conditioned media to astrocyte-neuron cocultures blocked P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth (Figure 6a), whereas conditioned media from the scrambled siRNA control allowed P4-E2 antagonism. LPS-activation showed similar responses to Pgrmc1 siRNA knockdown in blocking P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth (Figure 6b). Thus, in both modes of microglial activation, sufficient microglial Pgrmc1 expression is necessary for the generation of the SA required for P4 antagonism of neurite outgrowth.

Figure 6.

Requirement of Pgrmc1 in Activated Microglial conditioned media (CM)-Mediated P4 Antagonism. a, Microglia were plated and treated with siRNA followed by scratch wounding. CM were collected from scrambled siRNA and Pgrmc1 siRNA-treated wounded microglia and used for steroid treatment of wounded astrocyte-neuron cocultures. Add-back of CM from wounded/scrambled siRNA-treated microglia to astrocyte-neuron cocultures resulted in P4–E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth (neurite number: Veh, 11.2 ± 0.4; E2, 15.4 ± 0.9; E2+P4, 12.0 ± 0.4; P < .0001). P4 did not antagonize E2-induced neurite outgrowth (P < .001), whereas E2 still increased neurite outgrowth 40% (P < .0001) in CM from wounded/Pgrmc1 siRNA-treated microglia (neurite number: Veh, 10.3 ± 0.5; E2, 14.4 ± 0.9; E2+P4, 13.5 ± 0.5; P < .001). b, Microglia were treated with Pgrmc1 siRNA followed by LPS (100 ng/mL) to induce microglial activation. CM from activated microglia was introduced before steroid treatment of wounded astrocyte-neuron cocultures. When CM from scrambled siRNA/LPS-treated microglia were added to astrocyte-neuron cocultures, E2 increased neurite outgrowth 69% (P < .0001). P4 antagonized E2-induced neurite outgrowth in this CM (neurite number: Veh, 5.1 ± 0.2; E2, 8.6 ± 0.5; E2+P4, 5.4 ± 0.4; P < .0001). When CM from Pgrmc1 siRNA/LPS-treated microglia were added to astrocyte-neuron cocultures, E2 increased neurite outgrowth 52% (P < .0001). However, P4 did not antagonize E2-induced neurite outgrowth (P < .0001) (neurite number: Veh, 6.6 ± 0.3; E2, 10.0 ± 0.5; E2+P4, 9.8 ± 0.5; P < .0001). c, CD11b protein was induced 120% by LPS treatment (P < .0001). Treatment of microglia with Pgrmc1 siRNA before LPS treatment decreased CD11b protein 56% vs scrambled siRNA/LPS-treated microglia (<0.04). Pgrmc1 protein in vehicle, LPS, and LPS and Pgrmc1 siRNA-treated microglia showed 53% induction after LPS treatment (P < .01). Treatment of LPS-treated microglia with Pgrmc1 siRNA caused 50% decrease in Pgrmc1 protein vs LPS/scrambled siRNA-treated microglia (P < .01). *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001.

Furthermore, microglial activation by LPS is also attenuated by prior Pgrmc1 knockdown, assayed by the induction of CD11b and of Pgrmc1 (Figure 6c).

Nonwounded cocultures do not show P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth

The requirement for microglial activation suggests that unwounded glia-neuron cocultures without glial activation would not show P4 antagonism of the E2-induced neurite outgrowth. As shown in Figure 7, E2 induced neurite outgrowth in nonwounded glia-neuron cocultures. However, there was no P4-E2 antagonism.

Discussion

We report a new role of microglia in the steroidal regulation of neurite outgrowth in response to axonal injury and a new role of Pgrmc1, a nonclassical Pgr with multiple functions. These experiments extend our observations on the wounding-in-a-dish model of E18 neurons in coculture with astrocytes or mixed glia (1:3, microglia-astrocytes), in which P4 antagonized E2-dependent neurite outgrowth with mixed glia, but not with astrocytes alone (2). First, we confirmed the hypothesized requirement of microglia for the P4 antagonism of E2-induced neurite outgrowth, by microglial add-back to reconstitute mixed glia. Second, conditioned media from isolated microglia restored the P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth, but only if microglia were activated. Third, the SA in conditioned media from activated microglia required for P4-E2 antagonism depends on Pgrmc1 expression in microglia, as shown by siRNA knockdown. E2-dependent neurite outgrowth, however, was not altered by Pgrmc1 knockdown. Fourth, Pgrmc1 was induced during activation of microglia by LPS or scratch wounding. Fifth, microglial activation by LPS was blocked by Pgrmc1-siRNA knockdown.

The role of Pgrmc1 in neuritic responses to P4 is the first evidence for a role of any Pgr or mediator in microglia, which do not express the classical Pgr (4) as confirmed here. These studies extend the known functions of microglia beyond their established functions in phagocytosis of cell debris after injury (26) and in synaptic pruning during development (27). The microglial role in P4-E2 antagonism may be relevant to the use of progestins as a therapy for ischemic damage and traumatic brain injury, and in the postmenopausal hormone therapy (HT) for Alzheimer's disease.

Microglial activation by either scratch wounding (Figure 4) or LPS (Figure 5) induced the SA in conditioned media that mediates P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth in astrocyte-neuron cocultures. The requirement for microglial activation to produce the activity in conditioned media may explain the absence of P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth in unwounded cultures of mixed glia or of astrocytes (Figure 7). These findings suggest that in vivo P4-E2 interactions could be altered by microglial activation in response to acute injury and chronic neurodegenerative conditions, or even by the mild normative microglial activation of middle age (28). For example, would the absence of P4-E2 antagonism in Pgrmc1 induction in hippocampal neurons (16) be altered by brain inflammatory conditions? This question may be relevant to the outcomes of HT with combined estrogens and progestagens, discussed below.

We note several caveats. The neonatal glial responses might differ from glia of young adults or older ages. Nonetheless, the P4-E2 antagonism of neurite sprouting observed with neonatal glia in vitro also showed the P4-E2 antagonism of sprouting in vivo after perforant path lesions in young adult rats (1, 2). P4-E2 antagonism of sprouting in aging rats is difficult to study because aging impairs E2-dependent neurite outgrowth (29). Another concern is possible regional differences in glia between hippocampus studied in vivo (2) and cerebral cortex glia used for in vitro studies (present study and Ref. 2). Nonetheless, the P4-E2 antagonism was observed in both models. Although the isolated microglial studies used charcoal-stripped serum and no exogenous P4 was added, there could be a role of endogenously produced progestins. Lastly, we note that the measurements of neurite number and length cannot resolve if P4 caused neurite retraction, which would require time-lapse cinematography.

The role of P4 in this microglial activity was puzzling because microglia lack detectable expression of Pgr, the classical Pgr, first reported for ex vivo fluorescence-activated cell sorted microglia from adult mouse brain (4). We further verified the absence of Pgr expression in primary microglial cultures from neonatal rat by protein and RNA. Nonetheless, the classical Pgr that we found expressed in astrocytes (Figure 2a) has a role in the P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth, because in mixed glia-neuron cocultures, P4-E2 antagonism was blocked by 2 Pgr antagonists, RU486 and ORG-31710 (2).

Pgrmc1 was considered as a candidate for the microglial activity that mediates P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth because of its roles in axonal outgrowth during development (17, 18), and in microglial motility (20), which is relevant to microglial-neurite interactions. In vivo and in vitro, microglia definitively express Pgrmc1, assayed by mRNA and protein (Figure 2). The subcellular location of Pgrmc1 in astrocytes and microglia was prominent in the cell nucleus, as observed in hippocampal neurons (16) and ovarian granulosa cells (30, 31). Although Pgrmc1 lacks a nuclear localization signal (preliminary analysis; data not shown), its higher molecular weight forms in the nucleus are candidates for transcriptional regulation (31). Pgrmc1 was also associated with the cell surface membranes of epithelial and cancer cells (32) and cultured astrocytes (33), and with Ca2+channel activity in hypothalamic GnRH neurons (13).

The independence of exogenous P4 in generating the conditioned media activity from activated microglia is consistent with other Pgrmc1 functions that do not depend on exogenous P4: the microglial mobility dependent on Pgrmc1 that does not require exogenous P4 (20); Pgrmc1 orthologues that are transiently expressed in neurons also have roles in axonal guidance of nematodes (17) and mice (18) during developmental stages when systemic P4 does not have a defined role. Nonetheless, there may still be a role of microglial Pgrmc1 for direct P4 effects on neurite outgrowth, by its binding of P4 (9–13), as well as by indirect effects via enzymatic binding partners, eg, cytochrome P450 enzymes and P450 reductase (34–36).

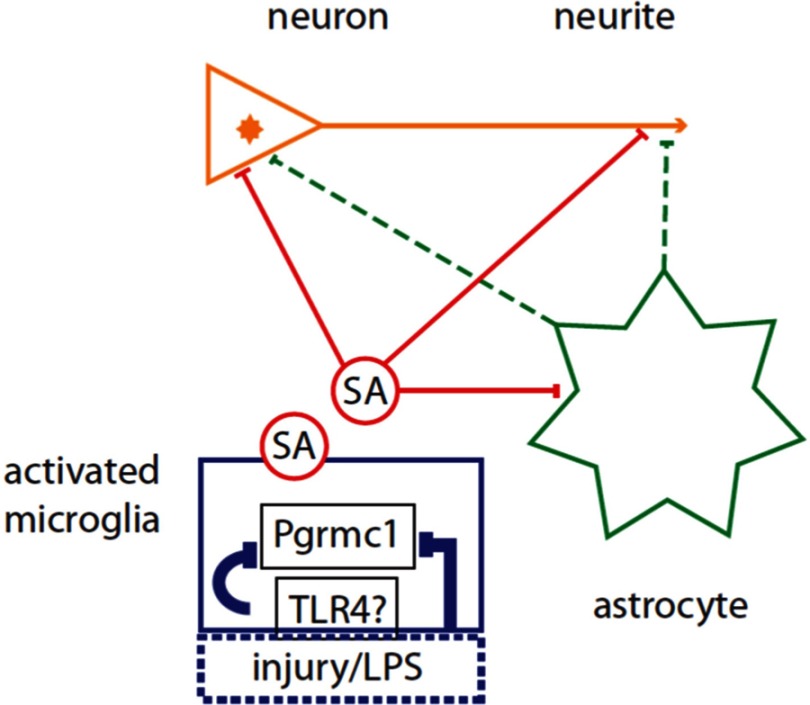

The mechanisms of Pgrmc1 in P4-E2 antagonism on neurite outgrowth involve many unknowns: the molecular nature of the Pgrmc1-dependent SA in conditioned media and the sites of its interactions, which may be multiple (Figure 8). Because E2-dependent neurite outgrowth is supported to the same extent by enriched astrocytes and microglia in present and prior studies (2), the Pgrmc1-dependent SA from activated microglia that mediates the P4-E2 antagonism of neurite outgrowth could interact with receptors on astrocytes as well as on neurons. Pgr is implicated because the P4 antagonism of E2-dependent neurite outgrowth was blocked by the drugs ORG-31710 and RU-486 (2). Thus, these mechanisms could include direct effects of the SA on neurons and indirect effects via astrocytes. A next obvious step is a proteomic analysis of conditioned media from activated vs resting microglia to identify prospective proteins that are shared in conditioned media from microglia activated by wounding and by LPS. Because LPS activates microglia through toll-like receptor-4 (37–39) and because microglial activation require Pgrmc1 (shown here), there may be links of Pgrmc1 to toll-like receptor-4 signaling pathways. Pgrmc1 could also interact with other proteins intracellularly. In addition to its binding of P450 components noted above, another partner is plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI1) RNA binding protein (PAIRBP1), also called SERPINE1 mRNA-binding protein (SERBP1) (40), which can influence microglial motility via levels of PAI1 (41).

Figure 8.

Targets of soluble activity (SA) from Activated Microglia and Microglial Pgrmc1 That Mediate the Antagonism of P4 on E2-Dependent Neurite Outgrowth. The schema shows 2 possibilities for SA action on neurites: direct effects (solid red lines) of the microglial SA on neurite outgrowth at the neurite growth cone (arrowhead) and/or involving the neuronal nucleus; indirect effects (dashed green lines) via astrocyte secretions on neurite or neuronal nucleus. Microglial activation by LPS is assumed to be mediated by toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) receptors (36, 37); activation by scratch wounding has unknown pathways. Glial activation by injury or LPS and the SA was blocked by Pgrmc1 knockdown.

The involvement of Pgrmc1 in microglial activation by LPS or scratch wounding suggests broader roles in immunity. Among recent findings, T cells, like microglia, express Pgrmc1, but not Pgr (42). In neutrophils, Pgrmc1 expression is associated with motility and is a transcriptional regulator of matrix metalloproteinase 9 activity (43). We do not know whether the activation of other monocytic lineage cells also induces Pgrmc1 expression and/or is blocked by Pgrmc1 knockdown, as observed for microglia.

P4 has both beneficial and detrimental effects on neuronal outcomes in injury and disease (44–49) that could involve Pgrmc1. In rodent models P4 can be neuroprotective for ischemia (50), traumatic brain injury (49), and spinal cord injury (51). The induction of Pgrmc1 by P4 in astrocytes after brain injury (20) could contribute to neuroprotection, by P4-dependent release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (33). The increased survival of CA1 neurons after ischemia could involve antiapoptotic actions of P4, such as mediated by Pgrmc1 in ovarian granulosa cells (52). In traumatic brain and spinal cord injury, P4 reduces edema (49), decreases glial activation (53), and reduces membrane lipid oxidation (54). P4 also antagonized E2-mediated protection from N-methyl-d-aspartate toxicity via brain-derived neurotrophic factor (55). These opposing effects of P4 (neuroprotection vs inhibition of neurite sprouting) could involve different mechanisms and receptors. Although Pgr-knockout mice have reduced benefit by P4 to ischemia (56), Pgrmc1 and the membrane Pgrs (progestin/adipoQ receptor gene family) merit study in ischemia.

The P4-E2 antagonism of neurite sprouting and synaptic plasticity are relevant to HT for menopause, in which progestins may be given in combination with estrogens. In the Women's Health Initiative trial, combined estrogen and progestins appeared to worsen cognitive decline during a 5-year follow-up (57). The negative effects of progestins on cognition may be consistent with P4-dependent regression of dendritic spines during normal estrous cycles in adult rats (58) and the P4 antagonism of E2-dependent neurite outgrowth after lesions (2).

In conclusion, we show a new role for Pgrmc1 in the microglial regulation of neurite outgrowth by P4 through a SA. Other P4-independent roles of Pgrmc1 include motility of microglia (21) and neutrophils (43), and cancer invasiveness (32). Thus, Pgrmc1/S2R may have broad roles in cell process regulation independent of P4 that are relevant to brain development as well as to neurodegenerative conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nahoko Iwata (Davis School of Gerontology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California) for conducting the PCRs.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 2P01 AG026572-06 (to R.D.B.); Project 2 (to C.E.F and T.E.M); and Animal Core (to T.E.M.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

- E2

- estradiol

- GFAP

- glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HT

- hormone therapy

- ICC

- immunocytochemistry

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- PAI

- plasminogen activator inhibitor

- Pgr

- progesterone receptor

- Pgrmc1

- Pgr membrane component 1

- P4

- progesterone

- SA

- soluble activity

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

References

- 1. Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Roles of estradiol and progesterone in regulation of hippocampal dendritic spine density during the estrous cycle in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336:293–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wong AM, Rozovsky I, Arimoto JM, et al. Progesterone influence on neurite outgrowth involves microglia. Endocrinology. 2009;150:324–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lefrançois T, Fages C, Peschanski M, Tardy M. Neuritic outgrowth associated with astroglial phenotypic changes induced by antisense glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) mRNA in injured neuron-astrocyte cocultures. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4121–4128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sierra A, Gottfried-Blackmore A, Milner TA, McEwen BS, Bulloch K. Steroid hormone receptor expression and function in microglia. Glia. 2008;56:659–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giulian D, Baker TJ. Characterization of ameboid microglia isolated from developing mammalian brain. J Neurosci. 1986;6:2163–2178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gatson JW, Simpkins JW, Yi KD, Idris AH, Minei JP, Wigginton JG. Aromatase is increased in astrocytes in the presence of elevated pressure. Endocrinology. 2011;152:207–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chiu JJ, Chien S. Effects of disturbed flow on vascular endothelium: pathophysiological basis and clinical perspectives. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:327–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brinton RD, Thompson RF, Foy MR, et al. Progesterone receptors: form and function in brain. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:313–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cahill MA. Progesterone receptor membrane component 1: an integrative review. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;105:16–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wendler A, Albrecht C, Wehling M. Nongenomic actions of aldosterone and progesterone revisited. Steroids. 2012;77:1002–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xu J, Zeng C, Chu W, et al. Identification of the PGRMC1 protein complex as the putative σ-2 receptor binding site. Nat Commun. 2011;2:380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gerdes D, Wehling M, Leube B, Falkenstein E. Cloning and tissue expression of two putative steroid membrane receptors. J Biol Chem. 1998;379:907–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu L, Wang J, Zhao L, Nilsen J, et al. Progesterone increases rat neural progenitor cell cycle gene expression and proliferation via extracellularly regulated kinase and progesterone receptor membrane components 1 and 2. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3186–3196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bashour NM, Wray S. Progesterone directly and rapidly inhibits GnRH neuronal activity via progesterone receptor membrane component 1. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4457–4469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johannessen M, Fontanilla D, Mavlyutov T, Ruoho AE, Jackson MB. Antagonist action of progesterone at σ-receptors in the modulation of voltage-gated sodium channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C328–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bali N, Arimoto JM, Iwata N, et al. Differential responses of progesterone receptor membrane component-1 (Pgrmc1) and the classical progesterone receptor (Pgr) to 17β-estradiol and progesterone in hippocampal subregions that support synaptic remodeling and neurogenesis. Endocrinology. 2012;153:759–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Intlekofer KA, Petersen SL. 17β-Estradiol and progesterone regulate multiple progestin signaling molecules in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus, ventromedial nucleus and sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area in female rats. Neuroscience. 2011;176:86–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Runko E, Kaprielian Z. Caenorhabditis elegans VEM-1, a novel membrane protein, regulates the guidance of ventral nerve cord-associated axons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9015–9026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Runko E, Wideman C, Kaprielian Z. Cloning and expression of VEMA: a novel ventral midline antigen in the rat CNS. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;14:428–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guennoun R, Meffre D, Labombarda F, et al. The membrane-associated progesterone-binding protein 25-Dx: expression, cellular localization and up-regulation after brain and spinal cord injuries. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57:493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cuevas J, Rodriguez A, Behensky A, Katnik C. Afobazole modulates microglial function via activation of both σ-1 and σ-2 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:161–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peluso JJ, DeCerbo J, Lodde V. Evidence for a genomic mechanism of action for progesterone receptor membrane component-1. Steroids. 2012;77:1007–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shao R, Markström E, Friberg PA, Johansson M, Billig H. Expression of progesterone receptor (PR) A and B isoforms in mouse granulosa cells: stage-dependent PR-mediated regulation of apoptosis and cell proliferation. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:914–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roy A, Fung YK, Liu X, Pahan K. Up-regulation of microglial CD11b expression by nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14971–14980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Qin L, Li G, Qian X, et al. Interactive role of the toll-like receptor 4 and reactive oxygen species in LPS-induced microglia activation. Glia. 2005;52:78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Neumann H, Kotter MR, Franklin RJ. Debris clearance by microglia: an essential link between degeneration and regeneration. Brain. 2009;132:288–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Kautzman AG, et al. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron. 2012;74:691–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morgan TE, Xie Z, Goldsmith S, et al. The mosaic of brain glial hyperactivity during normal ageing and its attenuation by food restriction. Neuroscience. 1999;89:687–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stone DJ, Rozovsky I, Morgan TE, et al. Effects of age on gene expression during estrogen-induced synaptic sprouting in the female rat. Exp Neurol. 2000;165:46–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peluso JJ, Liu X, Gawkowska A, Lodde V, Wu CA. Progesterone inhibits apoptosis in part by PGRMC1-regulated gene expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;320:153–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peluso JJ, Lodde V, Liu X. Progesterone regulation of progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (PGRMC1) sumoylation and transcriptional activity in spontaneously immortalized granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3929–3939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mir SU, Ahmed IS, Arnold S, Craven RJ. Elevated progesterone receptor membrane component 1/σ-2 receptor levels in lung tumors and plasma from lung cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:E1–E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Su C, Cunningham RL, Rybalchenko N, Singh M. Progesterone increases the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor from glia via progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (Pgrmc1)-dependent ERK5 signaling. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4389–4400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Oda S, Nakajima M, Toyoda Y, Fukami T, Yokoi T. Progesterone receptor membrane component 1 modulates human cytochrome p450 activities in an isoform-dependent manner. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39:2057–2065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rohe HJ, Ahmed IS, Twist KE, Craven RJ. PGRMC1 (progesterone receptor membrane component 1): a targetable protein with multiple functions in steroid signaling, P450 activation and drug binding. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121:14–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Szczesna-Skorupa E, Kemper B. Progesterone receptor membrane component 1 inhibits the activity of drug-metabolizing cytochromes P450 and binds to cytochrome P450 reductase. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:340–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lehnardt S, Massillon L, Follett P, et al. Activation of innate immunity in the CNS triggers neurodegeneration through a Toll-like receptor 4-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8514–8519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen Z, Jalabi W, Shpargel KB, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation and neuroprotection against experimental brain injury is independent of hematogenous TLR4. J Neurosci. 2012;32:11706–11715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Noreen M, Shah MA, Mall SM, et al. TLR4 polymorphisms and disease susceptibility. Inflamm Res. 2012;61:177–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peluso JJ, Yuan A, Liu X, Lodde V. Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 RNA-binding protein interacts with progesterone receptor membrane component 1 to regulate progesterone's ability to maintain the viability of spontaneously immortalized granulosa cells and rat granulosa cells. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jeon H, Kim JH, Kim JH, Lee WH, Lee MS, Suk K. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 regulates microglial motility and phagocytic activity. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ndiaye K, Poole DH, Walusimbi S, et al. Progesterone effects on lymphocytes may be mediated by membrane progesterone receptors. J Reprod Immunol. 2012;95:15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mir SU, Jin L, Craven RJ. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) expression is dependent on the tumor-associated σ-2 receptor S2RPgrmc1. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:14494–14501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Behl C, Skutella T, Lezoualc'h F, et al. Neuroprotection against oxidative stress by estrogens: structure-activity relationship. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:535–541 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Carroll JC, Rosario ER, Chang L, et al. Progesterone and estrogen regulate Alzheimer-like neuropathology in female 3xTg-AD mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13357–13365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Singer CA, Figueroa-Masot XA, Batchelor RH, Dorsa DM. The mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway mediates estrogen neuroprotection after glutamate toxicity in primary cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2455–2463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wise PM, Dubal DB. Estradiol protects against ischemic brain injury in middle-aged rats. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:982–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hua F, Wang J, Ishrat T, et al. Genomic profile of Toll-like receptor pathways in traumatically brain-injured mice: effect of exogenous progesterone. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shear DA, Galani R, Hoffman SW, Stein DG. Progesterone protects against necrotic damage and behavioral abnormalities caused by traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2002;178:59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Morali G, Letechipía-Vallejo G, López-Loeza E, Montes P, Hernández-Morales L, Cervantes M. Post-ischemic administration of progesterone in rats exerts neuroprotective effects on the hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 2005;382:286–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Labombarda F, González Deniselle MC, De Nicola AF, González SL. Progesterone and the spinal cord: good friends in bad times. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2010;17:146–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Peluso JJ, Liu X, Gawkowska A, Johnston-MacAnanny E. Progesterone activates a progesterone receptor membrane component 1-dependent mechanism that promotes human granulosa/luteal cell survival but not progesterone secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2644–2649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pettus EH, Wright DW, Stein DG, Hoffman SW. Progesterone treatment inhibits the inflammatory agents that accompany traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2005;1049:112–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Roof RL, Hoffman SW, Stein DG. Progesterone protects against lipid peroxidation following traumatic brain injury in rats. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1997;31:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Aguirre CC, Baudry M. Progesterone reverses 17β-estradiol-mediated neuroprotection and BDNF induction in cultured hippocampal slices. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:447–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Liu A, Margaill I, Zhang S, Labombarda F, et al. Progesterone receptors: a key for neuroprotection in experimental stroke. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3747–3757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, et al. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2663–2672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Estradiol mediates fluctuation in hippocampal synapse density during the estrous cycle in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2549–2554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]