Abstract

As laparoscopic hernia repair is slowly becoming the norm in the management of inguinal hernia, its remotely possible long-term complications have started becoming evident. We report an asymptomatic hanging anterior bladder wall calculus, formed over a migrated hernia mesh into the bladder 16 years after laparoscopic hernia repair and managed using holmium laser while performing transurethral resection of the prostate. There are only a few case reports in the literature regarding this issue, and the management suggested has been either periurethral cystoscopic pulling for extraction of the mesh or resection of mesh along with the bladder wall and cystorrhaphy. This is the first report of holmium laser being used for complete successful endourological management with a 2-year follow-up of protruded mesh in the bladder.

Keywords: Hernia mesh, Bladder stone, Holmium laser, Bladder erosion

Introduction

As laparoscopic hernia repair is slowly becoming the norm in the management of inguinal hernia, its remotely possible long-term complications have started becoming evident. We report an asymptomatic hanging anterior bladder wall calculus 16 years after laparoscopic hernia repair, diagnosed during workup for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and managed using holmium laser while performing transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).

Case Report

A man aged 67 years with a history of undergoing right-sided laparoscopic mesh hernia repair 16 years back presented with new-onset lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) due to BPH, and during workup, he was found to have a bladder calculus that was curiously not in a dependent position. A computed tomography (CT) scan and a skiagram of the pelvis were obtained, and those confirmed an anterior bladder wall vesical calculus (Fig. 1a, b). The patient was posted for a cystolithotripsy and TURP. The calculus was adherent on the right anterolateral wall; as it was broken with pneumatic lithotrite, hernia mesh was revealed which had eroded into the bladder (Fig. 2a). We used 30-W holmium laser to cut the eroded portion of the hernia mesh and the calculus embedded within the pores and underneath it. The TURP was completed in a standard manner after the mesh had been dealt with. The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged 2 days after the surgery. A follow-up cystoscopy at 4 months and 1 year revealed a non-epithelialized bladder mucosa and a tiny speck of calcification (Fig. 2b). The patient continues to remain asymptomatic after 2 years of follow-up, and recent X-ray of the pelvis did not show any stone recurrence (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

a CT scan picture of anterior wall bladder calculus; b X-ray of the pelvis showing the calculus; c X-ray of the pelvis at 2 years of follow-up

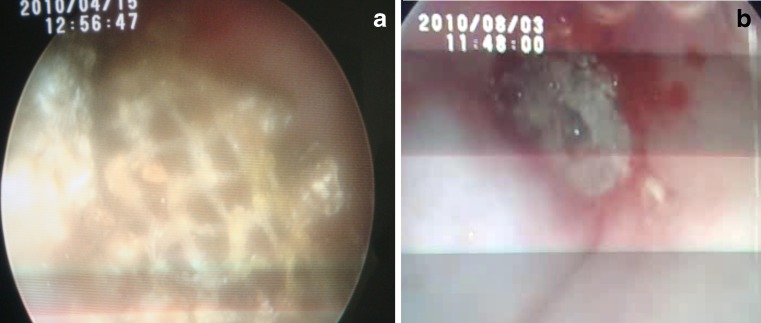

Fig. 2.

a Cystoscopic view of eroded hernia mesh after cystolithotripsy; b follow-up cystoscopy at 4 months

Discussion

Very few such cases of bladder complications due to mesh migration after laparoscopic repair have been reported with various presentations [1–4]. Three patients have presented with hematuria; two, with colovesical fistula; two, with recurrent urinary tract infection; and one patient each, with dysuria, a sinus, and a bladder stone. This is the first report of presentation as an asymptomatic hanging calculus. Such migrations have been more common after transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) repair than after total extraperitoneal repairs. It occurs more frequently after non-fixation of the mesh [1]. Our case was a follow-up of TAPP, but details regarding mesh fixation were not available.

Agarwal and Avill [5] have discussed mesh migration following inguinal hernia repair and concluded such migration to be either primary mechanical migration occurring in adjoining tissue spaces along paths of least resistance or secondary migration through trans-anatomical planes due to foreign body-induced reactions.

Laparoscopic repair of hernia is still a new operation, and such long-term complications were not known till recently. Whether it is an advantage over open mesh repair in unilateral hernias is still a controversy. There are no clear guidelines for the management due to rarity of presentations or under reporting. Simple cystoscopic pull out of the mesh was reported by Agarwal and Avill [5], but most patients will have a dense fibrous tissue around the mesh preventing such removal. Moreover, as the presence of mesh invokes severe inflammatory response in both genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts, what is stuck around the mesh outside the bladder will never be known and can lead to iatrogenic bowel or ureteric complications. Thus, pulling at the mesh to extract it can lead to complications and should not be attempted. Hume and Bour [6] and Kocot et al. [2] had to resort to partial cystectomy with resection of mesh-containing wall, which seems to be a more logical and safer option.

Our patient was completely asymptomatic after the hernia surgery for 16 years and had presented to us with BPH; hanging calculus was an incidental finding. Thus, although only the migrated portion of the mesh could be removed endoscopically during TURP, we believed it to be good enough for an asymptomatic presentation. In spite of an incomplete removal, the need for an open or laparoscopic exploration, removal and repair of bladder should not be considered until the patient again develops symptoms or presents with a local sepsis. The speck of calcification seen at cystoscopy does raise a concern for stone recurrence, and thus, the patient has been advised a yearly follow-up with an X-ray of the pelvis along with assessment of LUTS. This is the first report of use of Ho:YAG laser for cutting the migrated portion of hernia mesh. In the absence of any guidelines, such cases will continue to be managed on individual expertise and preference, and a clear view can only emerge with time when more of such cases are reported.

References

- 1.Hamouda A, Kennedy J, Grant N, Nigam A, Karanjia N. Mesh erosion into the urinary bladder following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair; is this the tip of the iceberg? Hernia. 2010;14:317–319. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kocot A, Gerharz EW, Riedmiller H. Urological complications of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: a case series. Hernia. 2011;15(5):583–586. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0696-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ngo T. Surgical mesh used for an inguinal herniorrhaphy acting as a nidus for a bladder calculus. Int J Urol. 2006;13(9):1249–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen JB, Jønler M, Lund L. Recurrent urinary tract infection due to hernia mesh erosion into the bladder. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2004;38(5):438–439. doi: 10.1080/00365590410031689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agrawal A, Avill R. Mesh migration following repair of inguinal hernia: a case report and review of literature. Hernia. 2006;10:79–82. doi: 10.1007/s10029-005-0024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hume RH, Bour J. Mesh migration following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1996;6(5):333–335. doi: 10.1089/lps.1996.6.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]