Abstract

The present work was aimed to investigate the impact of the solid substrates mixture on Fructosyltransferases (FTase) and Fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) production. An augmented simplex lattice design was used to optimize a three component mixture for FTase production. Among selected substrates corn cobs has highest impact on FTase production followed by wheat bran and rice bran. All two substrates and three substrate combinations showed the highest enzyme production than their individual levels. Among the tested various models quadratic model was found to be the best suitable model to explain mixture design. Corncobs, wheat bran and rice bran in a ratio of approximately 45:29:26 is best suitable for the FTase production by isolated Aspergillusawamori GHRTS. This study signifies mixture design could be effective utilize for selection of best combination of multi substrate for improved production of high value products under solid state fermentation.

Keywords: Mixture design, Fructosyltransferases, Fructooligosaccharides, FTase production, Mixed substrate, Solid state fermentation

Introduction

It is well known that there is a strong relationship between the food and health, which is a propellant force for the functional food market. Fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) produced from sucrose by several fungal fructosyltransferases (FTase, EC 2.4.1.9) have received attention as calorie-free and noncariogenic sweeteners. FOS also uses as a prebiotic compound, they stimulate the growth of bifidobacteria and have also been used in the prevention of colon cancer [1–3]. Therapeutically FOS also uses to reduce cholesterol, phospholipid and triglyceride levels in serum [4, 5]. These are also used as a protecting agents in swine from Escherichia coli infections and controlling swine odor. FOS has received GRAS status (generally recognized as safe) from the FDA (Food and Drug Administration U.S). Due to potential application in food and pharmaceutical industry FOS are one of the highest consuming functional food product in the world. It was estimated that in Japan alone these sugar has US$800 million turnover per annum [6].

FOS consists of a mixture of fructoseoligomers with two or three fructose units bound to the β-2,1 position of sucrose and they are mainly composed of 1-kestose, 1-nystose and 1-fructofuranosyl-nystose. FOS are found in small amounts in vegetables such as onion, garlic, Jerusalem artichokes, asparagus, bananas, rye, wheat and tomatoes. However, they are produced commercially through the enzymatic synthesis from sucrose by using microbial enzymes having FTase activity [1, 2, 4, 5, 7].

Mixture designs are one of the emerging techniques for the optimization of the media components [8, 9]. The key to mixture experiments is that the mixture components are subject to a constraint that the proportions sum must be one. This is the case when attempting to optimize the mixture of several substrates in the media, as the sum of the proportions of all substrate in each mixture must be 100 %. Mixture experiment design has been used as an alternative to factorial experiments in elucidating the effects of nutrient proportions in plant–herbivore relationships [10]. Mixture experiments have become a subject of many studies and have also been extensively applied in biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, geology, petroleum, food, and tobacco industries [8, 11]. In the present study, mixture design was employed to evaluate the influence of mixed solid substrates on the FTase production by isolated Aspergillusawamori GHRTS.

Materials and Methods

Microorganism and Inoculum Preparation

An isolated A. awamori GHRTS (MTCC 9625) was used in this study. The culture was maintained on potato dextrose agar slants at 4 °C after growth. The microorganism were grown regularly in a medium (pH 5.5) consisting of sucrose-10 g/L, yeast extract-2 g/L, KH2PO4-0.5 g/L, K2HPO4-0.5 g/L and MgSO4-0.5 g/L and incubated at 28 °C. Spore suspension of 108 spores/mL was prepared under sterile conditions and used as inoculums for further experiments.

Preparation of Solid Substrates

Various agro-industrial waste materials were evaluated as a support as well as substrate for the FTase production. 10 g of each substrate was taken separately in 250 mL conical flask, moisturized with 10 mL of distilled water and sterilized. These substrates were inoculated with 2 mL of spore suspension. The content of the flasks were mixed thoroughly and incubated at 30 °C in the incubator in a slanting position to get maximum surface area. Fermentation was carried up to 96 h.

Enzyme Extraction and Assay

The crude enzyme was extracted by simple contact method [12] using 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 5.5). After fermentation the substrate was thoroughly mixed with 50 mL of buffer, the solution was filtered through the muscular cloth and the extraction process was repeated twice. All extracts were pooled and centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 15 min. Supernatant was collected and used as enzyme source. FTase assay was carried out according to Sangeetha et al. [7] 0.5 mL of supernatant was incubated with 1.5 mL of the substrate (50 % sucrose prepared in 0.1 M citrate buffer, pH 5.5) at 55 °C for 1 h. Enzyme activity was determined based on the glucose release after the reaction. The glucose released was measured using a glucose kit (GLUC, GOD-POD method; Bayer diagnostics India ltd, Baroda, India). One unit of FTase was defined as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 μmol of glucose in 1 min. Enzyme yield was expressed as units per gram dry substrate (U/gds).

Estimation of FOS

The FOS produced during the fermentation were analyzed by HPLC (LC-10A VP; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with a refractive index detector, using a polar-bonded phase column (SSExsil-NH2, 5 μm i.d., 250 × 4.6 mm) at room temperature with acetonitrile:water (75:25) as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The retention times of the individual FOS were compared with those of standards for identification. The final FOS was expressed as a percentage yield, based on the initial sucrose concentration.

Chemical Composition Analysis

All selected materials chemical composition was analyzed for its carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and sulfur composition using Elemental Analyzer (Model Vario EL, Elementar Germany).

Mixture Designs for Substrate Optimization

In order to observe the mixed substrate effect on FTase production 3 solid substrates were taken and their combinations and concentrations were optimized by employing the mixture design. In these designs the total proportions of the different factors must be 100 % that is 10 g using 3 solid substrates. An augmented simplex lattice design was employed for the present study. The design consists a total of 10 runs where three experiments consist of pure mixtures (one for each component), three binary blends for each possible two-component blend, 3 three complete blends (all three components are included but not in equal proportions) and one centroid where equal proportions of all three components are included in this blend. Table 1 depicts the all 10 runs, the measured response of FTase production was assumed to be dependent on the relative proportions of the components in the mixture.

Table 1.

Mixture design used in this study, experimental results obtained for the dependent variables and predicted values by quadratic model

| S. no. | Corncobs (g) (X1) | Wheat bran (g) (X2) | Rice bran (g) (X3) | FTase activity (U/gds) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coded | Real | Coded | Real | Coded | Real | Observed | Predicted | Error | |

| 1 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6,210.000 | 6,150.408 | 59.592 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 5,568.000 | 5,498.499 | 69.501 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 3,212.000 | 3,346.954 | −134.954 |

| 4 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 6,638.000 | 6,643.426 | −5.426 |

| 5 | 0.5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 5 | 6,424.000 | 6,633.880 | −209.880 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.5 | 5 | 6,212.000 | 6,411.971 | −199.971 |

| 7 | 0.666667 | 6.7 | 0.166667 | 1.65 | 0.166667 | 1.65 | 6,959.000 | 6,997.396 | −38.396 |

| 8 | 0.166667 | 1.65 | 0.666667 | 6.7 | 0.166667 | 1.65 | 6,638.000 | 6,706.123 | −68.123 |

| 9 | 0.166667 | 1.65 | 0.166667 | 1.65 | 0.666667 | 6.7 | 6,531.000 | 5,985.759 | 545.241 |

| 10 | 0.333333 | 3.35 | 0.333333 | 3.35 | 0.333333 | 3.3 | 7,067.000 | 7,084.583 | −17.583 |

Analysis of the mixture models differs from the response surfaces models because of the constraint Σxi = 1. Linear to cubic models were used to simulate the best blend of components for optimal medium.

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

where Y is a response, βi is a linear, βij is a quadratic and βijk cubic coefficients, δij is a parameter of the model. The βixi represents linear blending portion and the parameters βij represents either synergic or antagonistic blending.

Results and discussion

The solid substrate availability and cost of the materials are the major limiting factors in the SSF along with other process parameters [12]. Keeping this is in view several agro-industrial waste materials were screened for the FTase production. The data indicated that FTase production pattern varied with the type of agro-industrial waste materials used. Maximum enzyme production (6,120 U/gds) was observed with corn cobs (Fig. 1) followed by wheat bran (5,537 U/gds) and rice bran (3,168 U/gds). Minimum FTase production was noticed with husks of green gram (251 U/gds) and bengal gram (500 U/gds). The production of FOS is also follows the similar pattern. The variation of the production is attributed due to variation in the composition of the solid material. Table 2 presents the carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen percentage present in the substrates. Sathish et al., [8] reported that the solid substrate composition plays a vital role in the production of the enzymes. In the present study the FTase produced by the A. awamori GHRTS shows the much higher than the literature reports. Whereas Sangeetha et al. [7] reported that 22 U/mL/min of FTase was produced by the Aspergillus oryzae CFR 202 using rice bran as solid substrate and they reported that wheat bran & corn germ are the best sources for the enzyme production next to the rice bran. The FTase produced from the corncobs, wheat bran and rice bran were tested for the FOS production. The enzyme produced from the 3 materials have the capability to produce the trisaccharide (GF2), tetrasaccharide (GF3) and pentasaccharide (GF4). The amount of FOS release is in accordance to their enzyme activity. In order to improve the enzyme production mixed substrates experiments were carried out with corn cobs, wheat bran and rice bran.

Fig. 1.

Effect of different substrates on FTase production. WB wheat bran, RB rice bran, OB oat bran, CC corncobs, SCB sugar cane bagasse, RgH redgram husk, GGH green gram husk, BeH bengal gram husk, BlH black gram husk, GC ground nut oil cake, SC spent coffee, ST spent tea, PW pineapple waste, PF palm seed fiber, CoC coconut oil cake

Table 2.

Chemical composition of different agro-industrial waste materials

| Name | Carbon (%) | Nitrogen (%) | Hydrogen (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat bran | 49.81 | 0.7 | 6.11 |

| Rice bran | 48.39 | 0.89 | 5.43 |

| Oat bran | 40.62 | 0.31 | 4.31 |

| Corn cob | 53.61 | 1.91 | 8.97 |

| Sugar cane bagasse | 48.32 | 0.2 | 7.84 |

| Redgram husk | 42.23 | ND | 5.52 |

| Green gram husk | 43.17 | 1.86 | ND |

| Bengal gram husk | 42.45 | 0.75 | 5.82 |

| Black gram husk | 39.61 | 2.34 | 5.87 |

| Ground nut oil cake | 40.34 | 2.31 | 4.21 |

| Spent coffee | 34.51 | 0.36 | 3.95 |

| Spent tea | 32.61 | 0.31 | ND |

| Pineapple waste | 45.68 | 0.61 | 3.97 |

| Palmoil fiber | 41.4 | 1.67 | 5.44 |

| Coconut oil cake | 48.16 | 1.69 | 5.15 |

ND not detectable

Mixture Design

The solid substrate composition was optimized with the help of mixture design. This design consists of 10 experiments with various combinations of corn cobs, wheat bran, and rice bran. In all experiments FTase and FOS production followed the similar pattern and also given the similar statistical results, to reduce the complexity in the design explanation, this part is limiting to FTase only. It was noticed that FTase production was varied within the range of 3,212–7,026 U/gds (Table 1). All 2 & 3 combinations of selected solid materials showed the higher enzyme production than their individual levels, this is attributed due to change in the overall composition of the substrates with respect to sugars and nitrogenous compounds. Sangeetha et al. [7] observed that addition of rice bran to bagasse and tippi in the 7:3 ratio enhanced FTase production in 20 and 35 % respectively. It is higher than the addition of ammonium sulphate and urea.

Sarria-Alfonso et al. [13] reported that mixture of rice husk and glucose in the ration of 1:2.5 respectively, increased the laccase production and biomass of Pleurotus spp. Indicating that mixing of the two solid substrates has the great impact on the enzyme production. In the Table 1 experimental runs from 7–10 indicates the various combinations of 3 selected solid materials. In these combinations 10th run where all 3 components are blended in equal proportions showed the highest enzyme (7,026 U/gds) production.

Further the design was analyzed by employing a multiple linear regression analysis by taking the FTase production as a response. To select an appropriate type of model sequential F tests were performed, starting with a linear to full cubic model. The ANOVA results of all four models are depicted in the Table 3. From the Table 3 it is observed that only quadratic model is significant and remaining all other models (linear, special cubic and cubic) are insignificant. The quadratic model has high F value (21.01) and low P value (0.0064). Sathish et al. [8] and Yan et al. [14] also noticed that quadratic model is best suitable model for analysis of the mixture design. The special cubic and cubic models have the higher R2 value (R2specialcubic = 0.968 & R2cubic = 0.9942) than the quadratic model (R2quadratic = 0.9629). Even though cubic & special cubic models have the grater R2 values than the quadratic model, which have smaller F value (Fspecial cubic = 0.4831 & Fcubic = 2.267) and higher P values (Pspecial cubic = 0.5369 & Pcubic = 0.4250). According to Rispoli and Shah [11] the model which have the higher R value and lower P value are significant based on this the cubic and special cubic models were rejected and further analysis was carried out with the quadratic model only.

Table 3.

Different models ANOVA and quadratic model regression coefficients

| Model | SS | MS | F value | P value | R2 | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | 4,197,504 | 2,098,752 | 2.10711 | 0.192155 | 0.375793 | 0.197448 |

| Quadratic | 6,557,861 | 2,185,954 | 21.10129 | 0.006490 | 0.962902 | 0.916530 |

| Special cubic | 57,479 | 57,479 | 0.48316 | 0.536996 | 0.968048 | 0.904144 |

| Cubic | 292,409 | 146,204 | 2.26723 | 0.425072 | 0.994227 | 0.948041 |

| Quadratic model terms | ||||||

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X1*X2 | X1*X3 | X2*X3 | |

| Coefficients | 6,150.408 | 5,498.499 | 3,346.954 | 3,275.889 | 7,540.798 | 7,956.980 |

| t value | 19.81368 | 17.71354 | 10.78229 | 2.28979 | 5.27090 | 5.56180 |

| P value | 0.000038 | 0.000060 | 0.000420 | 0.083876 | 0.006208 | 0.005117 |

SS sum of squares, MS mean square

The empirical relationship between FTase production (Y) and the 3 test variables in coded units obtained by the application of second order model is given by Eq. 5.

|

5 |

where Y is response FTase production in U/gds and X1–X3 are the coded values of the test variables as per the Table 1. The significance of each coefficient was determined by Student’s t test and P values, which were listed in Table 3. Among the linear terms corn cob has the highest magnitude (6,150.40) and lowest P value (0.00003) followed by the wheat bran and rice bran indicating that corn cob has the highest influence on the FTase production this is also evident from the Table 1. Where as the interaction of corn cobs with wheat bran has no significance. The interaction of the wheat bran with rice bran showed the highest magnitude (7,956.98) and lowest P value (0.005117) than the interaction between the corn cobs and wheat bran.

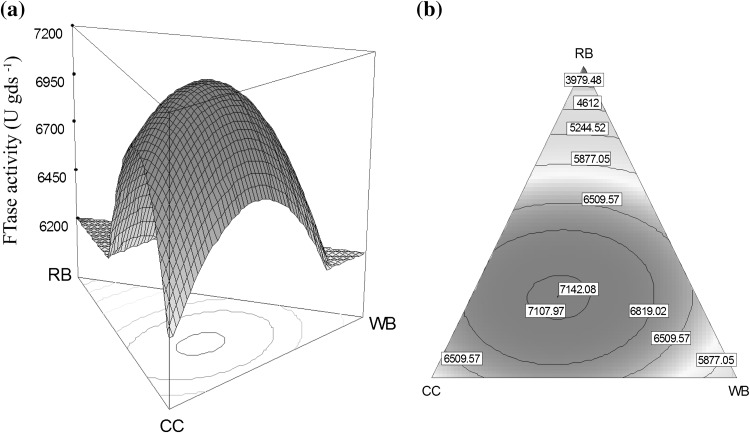

Triaxial diagrams are graphical representation of combinations of raw materials, rather than predictive illustration of product. The task of optimizing mixtures of different substrates could be carried out using a triangular surface response. Figure 2 represents the triangular graphs, which shows the level curves of FTase yield as a function of compositions obtained from Eq. 5. From the graph it was observed that the highest yield was observed near to the corn cob and wheat bran axial line.

Fig. 2.

Combination effect of 3 agricultural materials on FTase production. a Triaxial surface plot. b Triaxial contour plot

A numerical method given by Murugappan et al. [15] was used to solve the regression Eq. 5. The results indicated that 45.31 % corn cobs, 28.71 % wheat bran and 25.96 % rice bran combination is the best solid substrate/support for the enzyme production. At this combination the predicted FTase & FOS yield was 7,142 U/gds & 21.85 % respectively by conducting the validation experiments it was observed that 7,131 U/gds enzyme and 21.9 % FOS was produced by A. awamori GHRTS. Figure 3 depicts the growth of the fungal mycelia on the surface of the solid substrate mixture indicates, it is a best support for the growth of organism and promotes the production of extra cellular FTase. More than 15 % enzyme yield improvement was achieved by optimizing the composition of substrate mixture with the help of mixture designs.

Fig. 3.

SEM micrographs of Aspergillus awamori GHRTS growing on the surface of solid substrate

Conclusion

It is concluded that, the results presented in this paper showed that it was possible to obtain large amounts of FTase enzyme and FOS using very low cost substrates. Mixture design could be an effective method for selection of best combination of multi substrate for improved production of microbial enzymes under SSF. Due to low cost, worldwide abundance and high levels of FTase production in SSF using corn cobs, wheat and rice brans as substrates, and this method could be scale up to industrial level.

References

- 1.Chen H-Q, Chen X-M, Chen T-X, Xu X-M, Jin Z-Y. Extraction optimization of inulinase obtained by solid state fermentation of Aspergillus ficuum JNSP5-06. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;85:446–651. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ning Y, Wang J, Chen J, Yang N, Jin Z, Xu X. Production of neo-fructooligosaccharides using free-whole-cell biotransformation by Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Bioresource Technol. 2010;101:7472–7478. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nemukula A, Mutanda T, Wilhelmi BS, Whiteley CG. Response surface methodology: synthesis of short chain fructooligosaccharides with a fructosyltransferase from Aspergillus aculeatus. Bioresource Technol. 2009;100:2040–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maiorano AE, Piccoli RM, da Silva ES, de Andrade Rodrigues MF. Microbial production of fructosyltransferases for synthesis of pre-biotics. Biotechnol Lett. 2008;30:1867–1877. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9793-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar H, Pandey PK, Doiphode VV, Vir S, Bhutani KK, Patole, Shouche YS. Microbial community structure at different fermentation stages of Kutajarista, a herbal formulation. Indian J Microbiol. 2012;52(4):660–665. doi: 10.1007/s12088-012-0299-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jun H, Jiayi C. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for increased bioconversion of lignocellulose to ethanol. Indian J Microbiol. 2012;52:442–448. doi: 10.1007/s12088-012-0259-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sangeetha PT, Ramesh MN, Prapulla SG. Production of fructosyl transferase by Aspergillus oryzae CFR 202 in solid-state fermentation using agricultural by-products. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;65:530–537. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1618-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sathish T, Lakshmi GS, Rao ChS, Brahmaiah P, Prakasham RS. Mixture design as first step for improved glutaminase production in solid-state fermentation by isolated Bacillus. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2008;47:256–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prakasham RS, Sathish T, Brahmaiah P, Rao CS, Rao RS, Hobbs PJ. Biohydrogen production from renewable agri-waste blend: optimization using mixer design. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2009;34:6143–6148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sateesh L, Rodhe AV, Naseeruddin S, Yadav KS, Prasad Y, Rao LV. Simultaneous cellulase production, saccharification and detoxification using dilute acid hydrolysate of S. spontaneum with Trichoderma reesei NCIM 992 and Aspergillus niger. Indian J Microbiol. 2012;52:258–262. doi: 10.1007/s12088-011-0184-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rispoli FJ, Shah V. Mixture design as a first step for optimization of fermentation medium for cutinase production from Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;34:349–355. doi: 10.1007/s10295-007-0203-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.da Silva LCA, Honorato TL, Cavalcante RS, Franco TT, Rodrigues S. Effect of pH and temperature on enzyme activity of chitosanase produced under solid stated fermentation by Trichoderma spp. Indian J Microbiol. 2012;52:60–65. doi: 10.1007/s12088-011-0196-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarria-Alfonso V, Sánchez-Sierra J, Aguirre-Morales M, Gutiérrez-Rojas I, Moreno-Sarmiento N, Poutou-Piñales R. Culture media statistical optimization for biomass production of a ligninolytic fungus for future rice straw degradation. Indian J Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s12088-013-0358-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan Z-L, Cao X-H, Liu Q-D, Yang Z-Y, Teng Y-O, Zhao J. A shortcut to the optimization of cellulase production using the mutant Trichoderma reesei YC-108. Indian J Microbiol. 2012;52:670–675. doi: 10.1007/s12088-012-0311-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murugappan RM, Aravinth A, Rajaroobia R, Karthikeyan M, Alamelu MR. Optimization of MM9 medium constituents for enhancement of siderophoregenesis in marine Pseudomonas putida using response surface methodology. Indian J Microbiol. 2012;52:433–441. doi: 10.1007/s12088-012-0258-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]