Abstract

Various aspects of the genetics of the rat lungworm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, are reviewed. This nematode has an XX/XO sex-determination mechanism, with the female having a 2n = 12 (XX) and the male 2n = 11 (XO) chromosome constitution. Allozymes (12 loci) exhibit a low proportion of polymorphic loci (P = .08) and low mean heterozygosity (H = 0.43) in specimens from Hawai‘i, and no polymorphism or heterozygosity in specimens from Thailand. The phosphoglucomutase-2 (PGM-2) locus exhibits sex-limited expression, with no detectable enzyme activity in the male worms from either location. Based on the 12 allozyme loci, Nei's genetic distance between the Hawai‘i and Thailand isolates is D = 0.03. The p-distance (proportion of nucleotide sites) based on cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) is 3.61% between the Thailand and China isolates as well as between Thailand and Hawai‘i isolates, and 0.83% between China and Hawai‘i isolates. The partial DNA sequences of the 66 kDa protein gene show a great diversity of haplotypes, indicating both inter- and intra-population variation. Intra-specifc sequence variation is also found in the internal transcribed spacer regions. For the small-subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene, two distinct genotypes have been recorded.

Keywords: Allozymes, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Chromosome number, Emerging infectious disease, Eosinophilic meningitis, Genetics, Parasitology, Rat lungworm disease

Introduction

Angiostrongylus cantonensis, a metastrongyloid nematode, is a primary cause of human eosinophilic meningitis or meningoencephalitis in many parts of the world.1,2 Its life cycle involves a definitive rodent host and an intermediate molluscan host. The adult worms live in the pulmonary arteries of rats. Humans become infected by ingestion of the third stage larvae in molluscan intermediate hosts or paratenic hosts such as frogs, freshwater shrimp, crabs, and monitor lizards.1–3

Genetic diversity refers to both the vast numbers of different species as well as the diversity within a species, and any variation in the nucleotides, genes, chromosomes, or whole genomes of organisms. This short review summarizes what is known about genetic variation in A. cantonensis.

Chromosome Constitution

The two sexes of Angiostrongylus cantonensis differ in their diploid number because of an XX/XO sex-determination mechanism.4 The male has 2n = 11 with an XO sex-chromosome constitution, while the female has 2n = 12 with an XX sex-chromosome constitution. To date the karyotype of A. cantonensis has only been reported for individuals from Japan,5 Egypt,6 mainland China,7 Thailand,4 and Hawai‘i.4 There appear to be no similar studies of the other Angiostrongylus species.

Allozymes

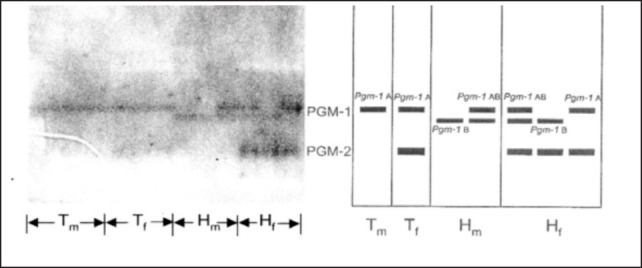

In the six allozyme systems studied in A. cantonensis from Hawai‘i and Thailand (glucose phosphate isomerase, hexokinase, lactate dehydrogenase, malate dehydrogenase, malic enzyme, and phosphoglucomutase), each represented by two presumptive loci and hence comprising 12 loci, there was only one polymorphic locus, PGM-1 (phosphoglucomutase-1), which was present only in Hawai‘i (Figure 1). Thus the proportion of polymorphic loci (P) was 0.08; mean heterozygosity (H) was 0.43.8 It was represented by two alleles in the following proportions: PGM-1A, 0.36 ± 0.03; PGM-1B, 0.64 ± 0.03. Nei's genetic distance (D) between specimens from Hawai‘i and Thailand is 0.03, indicating that they are genetically very similar. In contrast, the genetic distance between A. cantonensis and a congeneric species, A. malaysiensis, is 0.27.8 The very low proportion of polymorphic loci in specimens from Hawai‘i and the lack of polymorphism in those from Thailand may be attributed to the founder effect. The proportion of polymorphic loci in A. cantonensis in Japan has been reported to be 0.6.9

Figure 1.

Phosphoglucomutase allozyme system of Angiostrongylus cantonensis from Hawai‘i (H) and Thailand (T).

The PGM-2 locus is invariant, with a single band of enzyme activity in the female worms from both Thailand and Hawai‘i. However, there is no detectable enzyme activity at this locus in male worms from either location (Figure 1). This non expression or ‘null’ PGM-2 phenotype in the male worms is presumed to be an example of sex-limited gene expression.10

Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I (COI)

Angiostrongylus cantonensis samples from Thailand, Hawai‘i, and China form distinct clusters in maximum likelihood (ML), maximum parsimony (MP), neighbor-joining (NJ), and Bayesian inference (BI) trees.11 The p-distance (proportion of nucleotide sites) between the Thailand and China samples is 3.61%, between Thailand and Hawai‘i 3.61%, and between China and Hawai‘i 0.83%.

Phylogenetic analysis of 18 geographical isolates of A. cantonensis from Japan, mainland China, Taiwan, and Thailand showed eight distinct COI haplotypes.12 A single haplotype only was found in 16 of the 18 localities. However, two haplotypes coexisted in two localities. The low genetic variation of A. cantonensis in each location is attributed to founder effects.

The COI marker has proven useful for differentiating closely related species (eg, A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis), differentiating geographical isolates of A. cantonensis, and determining the phylogenetic relationships of A. cantonensis, A. costaricensis, A. malaysiensis, and A. vasorum.11 Based on COI sequences, A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis cluster to form a clade, while A. costaricensis and A. vasorum cluster to form another clade. The p-distance between A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis is 11.1–11.7%.11

Partial 66 kDa Protein Gene

The partial DNA sequences of the 66 kDa protein gene do not clearly distinguish A. cantonensis from Thailand, China, Japan, and Hawai‘i.13 They are represented by a great diversity of haplotypes, indicating both inter- and intra-population variation. The AC primers13 successfully amplified genomic DNA of A. cantonensis, A. costaricensis, and A. malaysiensis. They did not amplify DNA of Ascaris suum, Ascaris lumbricoides, Toxocara canis, Anisakis simplex, Trichinella spiralis, Ancylostoma caninum, and Strongyloides ratti. Based on the 66 kDa gene, the genetic distance between A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis is P = 1.70%–4.08%, between A. cantonensis and A. costaricensis P = 3.77%–5.77%, and between A. malaysiensis and A. costaricensis P = 5.10%.13 Partial DNA sequences indicate that A. cantonensis is sister to A. malaysiensis. The two species are clearly distinct but are more closely related to each other than to A. costaricensis.

Internal Transcribed Spacer Regions of Nuclear Ribosomal DNA

The DNA sequences of the internal transcribed spacer region-1 (ITS-1) in A. cantonensis from China, USA, and Brazil indicate intra-specifc sequence variation of 0.1–1.0%, and the sequence variation for ITS-2 is 0.0–1.3% in the China and Philippine isolates.14 ITS-2 sequences yield poorly resolved phylogenetic relationships among A. cantonensis, A. costaricensis (from Brazil and Costa Rica), and A. vasorum (from Brazil and Europe) as well as A. dujardini (from Europe) (PR, PEL, HSY unpublished).

Small-subunit Ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) Gene

Two distinct SSU genotypes (G1 and G2) were identified among 17 A. cantonensis, one from each of 17 localities in Japan, mainland China, Taiwan, and Thailand.12 Analysis of all available SSU rRNA sequences of Angiostrongylus species from GenBank indicates that A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis form a cluster (clade) distinct from A. costaricensis, A. dujardini, and A. vasorum (PR, PEL, HSY unpublished).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, the Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, and the University of Malaya (YHS: grants H-5620009 and H-50001-00-A000025) for financial support and facilities. We also thank the Editor of Tropical Biomedicine for permission to reproduce Figure 1. This paper represents a contribution to the Rat Lungworm Disease Scientific Workshop held at the Ala Moana Hotel, Honolulu, Hawai‘i in August 2011. Funding for the workshop and for this publication was provided by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture, through Award No. 2011-65213-29954.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identifies any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Eamsobhana P. The Rat Lungworm Parastrongylus (= Angiostrongylus) cantonensis: Parasitology, Immunology, Eosinophilic meningitis, Epidemiology and Laboratory Diagnosis. Bangkok: Wankaew (IQ) Book Center; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eamsobhana P, Tungtrongchitr A. Angiostrongyliasis in Thailand. In: Arizono N, Chai JY, Nawa Y, Takahashi T, editors. Food-borne Helminthiasis in Asia. Chiba, Japan: The Federation of Asian Parasitologists; 2005. pp. 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cross JH, Chen ER. Angiostrongyliasis. In: Murrel KD, Fried B, editors. Food Borne Parasitic Zoonoses. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 263–290. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eamsobhana P, Yoolek A, Yong HS. Meiotic chromosomes and sex determination mechanism in Thailand and Hawaii isolates of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) Trop Biomed. 2009;26:346–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakaguchi Y, Nojima H. Chromosomes of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda, Metastrongylidae) Chromosome Information Service. 1980;28:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashour AA, Hassan NHA, Ibrahim AM, Soliman MI. Chromosomes and gametogenesis in the nematode Angiostrongylus cantonensis from Egypt. Egypt J Histol. 1993;16:497–503. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheng HX, Ding BL. Chromosome analyses of Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Chinese J Zoonoses. 1996;1:58. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eamsobhana P, Dechkum N, Yong HS. Biochemical genetic relationship of Thailand and Hawaii isolates of Parastrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) Biochem Syst Ecol. 2008;36:51–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawabe K, Makiya K. Genetic variability in isozymes of Angiostrongylus malaysiensis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1994;25:728–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eamsobhana P, Dechkum N, Yong HS. Polymorphic and sex-limited phosphoglucomutase in Parastrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) Trop Biomed. 2005;22:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eamsobhana P, Lim PE, Solano G, Zhang H, Gan X, Yong HS. Molecular differentiation of Angiostrongylus taxa (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) by cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene sequences. Acta Trop. 2010;116:152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tokiwa T, Harunari T, Tanikawa T, et al. Phylogenetic relationships of rat lungworm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, isolated from different geographical regions revealed widespread multiple lineages. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eamsobhana P, Lim PE, Zhang H, Gan X, Yong HS. Molecular differentiation and phylogenetic relationships of three Angiostrongylus species and A. cantonensis geographical isolates based on a 66-kDa protein gene of A. cantonensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) Exp Parasitol. 2010;126:564–569. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu CY, Zhang RL, Chen MX, et al. Characterisation of Angiostrongylus cantonensis isolates from China by sequences of internal transcribed spacers of nuclear ribosomal DNA. J Anim Vet Adv. 2011;10(5):593–596. [Google Scholar]