Abstract

The metastrongyloid nematode genus Angiostrongylus includes 18 species, two of which are relevant from a medical standpoint, Angiostrongylus costaricensis and Angiostrongylus cantonensis. The first was described from Costa Rica in 1971 and causes abdominal angiostrongyliasis in the Americas, including in Brazil. Angiostrongylus cantonensis, first described in 1935 from Canton, China, is the causative agent of eosinophilic meningitis. The natural definitive hosts are rodents, and molluscs are the intermediate hosts. Paratenic or carrier hosts include crabs, freshwater shrimp, amphibians, flatworms, and fish. Humans become infected accidentally by ingestion of intermediate or paratenic hosts and the parasite does not complete the life cycle as it does in rats. Worms in the brain cause eosinophilic meningitis. This zoonosis, widespread in Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands, has now been reported from other regions. In the Americas there are records from the United States, Cuba, Jamaica, Brazil, Ecuador, and Haiti. In Brazil seven human cases have been reported since 2007 from the southeastern and northeastern regions. Epidemiological studies found infected specimens of Rattus norvegicus and Rattus rattus as well as many species of molluscs, including the giant African land snail, Achatina fulica, from various regions of Brazil. The spread of angiostrongyliasis is currently a matter of concern in Brazil.

Keywords: Achatina fulica, Angiostrongyliasis, Brazil, Eosinophilic meningitis, Rattus norvegicus, Rattus rattus, Snails

Introduction

The metastrongyloid nematode Angiostrongylus cantonensis causes eosinophilic meningitis (and meningoencephalitis) in humans. This parasite, widespread in Southeast Asia and some Pacific islands, has now dispersed to other regions, including Latin America.1 The spread of this emerging zoonosis is correlated with increased tourism, commerce, and the diversification of habits and customs in certain countries, factors that have facilitated the dispersal of the definitive and intermediate hosts of A. cantonensis.2 In addition, the introduction of non-native molluscs plays an important role, as has been observed with the giant African snail, Achatina fulica, in Brazil3–5 and the South American freshwater snail Pomacea canaliculata in China.6 Species of Angiostrongylus can infect domestic dogs and wild mammals,7 as well as humans, as accidental hosts, causing parasitic diseases.8 Besides A. cantonensis, another congeneric species, A. costaricensis, described from Costa Rica in 1971,9 is important from a public health standpoint as the causative agent of abdominal angiostrongyliasis, a zoonosis recorded from the south of the United States to northern Argentina. In Costa Rica up to 500 human cases are reported annually.10 In Brazil cases have been reported mainly in the southern States.11 This paper focuses on A. cantonensis in Brazil.

Taxonomy

Attempts to organize the family Angiostrongylidae into genera and subgenera, based on the morphology of the rays of the caudal bursa and on the host species, have divided the scientific community, particularly in relation to the important human parasites, ie, A. cantonensis and A. costaricensis.

Dougherty12 synonymized the following genera with Angiostrongylus: Haemostrongylus, Parastrongylus, Pulmonema, Cardionema, and Rodentocaulus. Subsequently, Skrjabin et al.13 recognized four genera, accepting Dougherty's synonyms, with the exception of Rodentocaulus, which was retained as a valid genus along with two additional more recently described genera that were also considered valid, Rattostrongylus and Angiocaulus. Yamaguti14 accepted the systematic arrangement proposed by Skrjabin et al.13

In 1970 Drozdz5 proposed dividing the genus Angiostrongylus into two subgenera: Angiostrongylus (Angiostrongylus) with Haemostrongylus, Cardionema, and Angiocaulus as synonyms; and Angiostrongylus (Parastrongylus) with Rodentocaulus, Pulmonema, and Rattostrongylus as synonyms. Chabaud15 abolished the subgenera, and recognized four genera: Angiostrongylus (with synonyms Haemostrongylus, Cardionema, and Angiocaulus), Parastrongylus, Rodentocaulus, and his newly created genus Morerostrongylus. However, Anderson7 adopted the subgeneric classification of Drozdz, with Morerostrongylus as a synonym of Parastrongylus, which was treated as a subgenus of Angiostrongylus, but with the exception of recognizing Rodentocaulus as a distinct valid genus.

In 1986, Ubelaker16 reorganized the family Angiostrongylidae, recognizing the genera Angiostrongylus (synonym Haemostrongylus), Parastrongylus (synonyms Pulmonema, Rattostrongylus, Morerostrongylus, Chabaudistrongylus), Angiocaulus (synonym Cardionema), Rodentocaulus, Galegostrongylus (synonym Thaistrongylus), and Stefanskostrongylus. Although this is the most recent taxonomic revision of the Angiostrongylidae, based on morphological similarity of the bursal rays and host animals, it has not been widely accepted, since, for instance, few people use Parastrongylus for A. cantonensis. Too few molecular data are available to help resolve the systematics of the family.

Based on the classification of Dougherty,12 we recognize 18 species of Angiostrongylus from around the world (excluding those albeit nomenclaturally valid species that have been described on the basis only of female morphology). Angiostrongylus vasorum, A. raillieti, A. gubernaculatus, and A. chabaudi have carnivores as their definitive hosts. The remaining 14 species have rodents as definitive hosts: A. taterone, A. cantonensis, A. sciuri, A. mackerrasae, A. sandarsae, A. petrowi, A. dujardini, A. schmidti, A. costaricensis, A. malaysiensis, A. ryjikovi, A. siamensis, A. morerai, and A. lenzii.

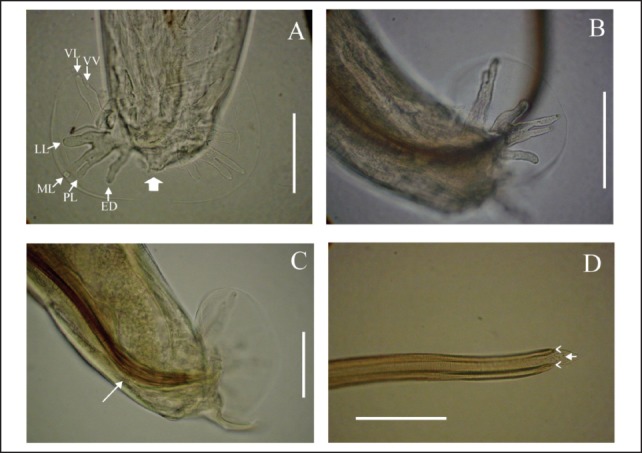

Angiostrongylus cantonensis was originally described in the genus Pulmonema from specimens recovered from the lungs of naturally infected rats (Rattus norvegicus and Rattus rattus) from Canton, China.17 The adult worms (Figure 1) are characterized by a filiform body in both sexes, tapering at the anterior end. Females are larger and more robust than males. Detailed morphological descriptions have been published elsewhere.18,19

Figure 1.

Angiostrongylus cantonensis; A. Male, dorsal view of caudal bursa, detail ventroventral (VV), ventrolateral (VL), laterolateral (LL), meiolateral (ML), posterolateral (PL), externodorsal (ED) and dorsal rays (large arrow); scale bar: 50 µm. B. Male, caudal bursa, lateral view; scale bar: 50 µm. C. Male, caudal bursa showing gubernaculum (white arrow), lateral view; scale bar: 50 µm. D. Male, detail of two spicules (arrowheads) joined by a sheath (arrow); scale bar: 100 µm.

Life Cycle and Hosts

The life cycle of A. cantonensis involves various species of terrestrial and freshwater gastropods as intermediate hosts and rats as definitive hosts.20–23 As A. cantonensis occurs in the adult stage in the pulmonary arteries of the definitive hosts, commonly Rattus rattus and R. norvegicus, it is known as the rat lungworm. In experimental infection of R. norvegicus, the female worm lays eggs inside the pulmonary arteries, where they develop into the first-stage larvae (L1), which then move to the interior of the alveoli. The larvae then migrate to the pharynx and are swallowed, pass through the gastrointestinal tract, and are eliminated in the feces.21,24 Land or freshwater snails are the principal intermediate hosts, and become infected either by ingestion of L1 in the rat feces or by penetration of these larvae through the body wall or respiratory pore.25 In the mollusc tissue the L1 molts twice (L2 and L3) and the period necessary for the development is around 20 days. Rats become infected mainly by the ingestion of intermediate hosts infected by L3 larvae. These larvae then penetrate the intestinal wall and enter the bloodstream a few hours after being ingested. They reach the pulmonary circulation from the heart and are dispersed to various other organs by the arterial circulation. Many reach the brain and molt again, becoming L4 larvae. The fifth molt into the subadult stage (L5) occurs in the subarachnoid space, from where, after developing further, they migrate to the pulmonary arteries where they are found 25 days after infection. The worms then reach sexual maturity at around 35 days and the L1 larvae can be found in the rodent's feces about 42 days after the exposure to the previous generation of L1 larvae.

Infection in humans occurs when they eat raw or undercooked snails and slugs, or paratenic hosts, including land crabs, freshwater shrimp, fish, frogs, and planarians.26 In humans, the young larvae reach the brain, where they die rather than migrating further and completing their development. This causes eosinophilic meningitis (or meningoencephalitis), which has neurological symptoms. Usually the infection does not kill the victim, except when there is massive exposure to infective L3 larvae.27

The parasite displays broad specificity for intermediate hosts; many species of terrestrial and freshwater molluscs have been found naturally infected, including Achatina fulica, Bradybaena similaris, Subulina octona, Pomacea canaliculata, Pomacea lineata, other Pomacea species, Deroceras laeve, and species of Pila.3,18,23,28 It has been found in various paratenic hosts, and although these are passive hosts in which the parasite does not undergo any development, they play an important role as they increase the opportunities for the parasite to infect definitive hosts.

In southern China, an apple snail species, Pomacea canaliculata, and the giant African snail, Achatina fulica, both non-native, are widespread and the number of cases of eosinophilic meningitis has been increasing, the transmission being linked to both species. Most recently, serious outbreaks have been reported, in most cases directly related to consumption of P. canaliculata.6,29

Angiostrongylus cantonensis and Angiostrongyliasis in Brazil

Sporadic outbreaks of eosinophilic meningitis caused by A. cantonensis were first reported in the Americas in the latter part of the twentieth century.30 The zoonosis, or at least infected rodents, have now been reported in the Americas and islands of the Caribbean from the United States,31 Cuba,32,33 Jamaica,34 Brazil,3,4,26 Ecuador,35 and Haiti.36

The first report of this zoonosis in Brazil was in the municipality of Cariacica, Espírito Santo State,3 with subsequent reports from two municipalities (Olinda and Escada) in Pernambuco State,18,26 and in the city of São Paulo, São Paulo State.37 In the first two states naturally infected definitive and/or intermediate hosts had been discovered during the epidemiological investigation of the human cases. Achatina fulica was considered the vector in three of the four reported cases.3,18,26 One of the cases in Pernambuco State was attributed to ingestion of undercooked apple snails (Pomacea lineata).18 Specimens of A. fulica have been found infected with A. cantonensis larvae in south and southeastern Brazil since 2007 and more recently from Pará State in the Amazon region, northern Brazil.38 A species of Pomacea was also associated with an outbreak of eosinophilic meningitis in Ecuador.35

Natural infection of definitive vertebrate hosts with A. cantonensis has also been reported in Brazil. Infected Rattus rattus and R. norvegicus have both been found in Pará State38 and infected R. norvegicus have also been reported in the States of Rio de Janeiro (southeastern Brazil)39 and Rio Grande do Sul (southern Brazil), according to Carlos Graeff-Teixeira (oral communication, June 2012 ). Some reports of infected rodents in urban areas were associated with epidemiological investigations following the occurrence of cases of eosinophilic meningitis.39 The prevalence of A. cantonensis in rodents is highly variable8 and does not suggest specificity among species in the genus Rattus.

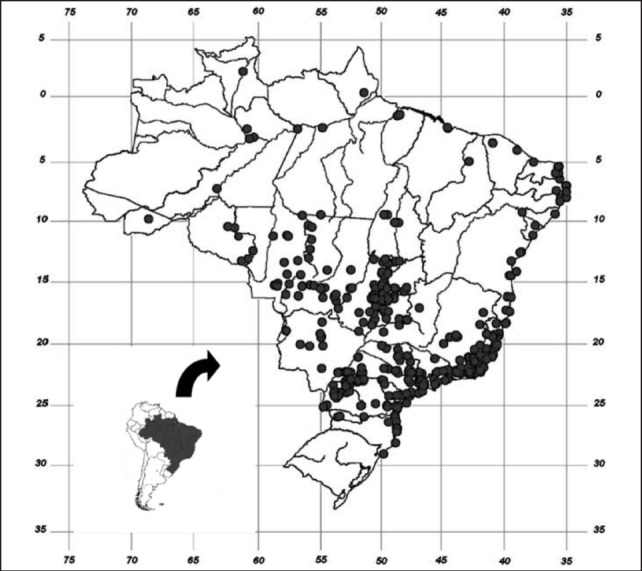

How A. cantonensis arrived and became established in the Americas is not well understood, although Diaz40 attributed its introduction to introduction of Rattus norvegicus in shipping containers. Its introduction to Brazil has been postulated as either with parasitized rats during the country's colonial period (1500–1822), when there was frequent contact with Africa and Asia4 and/or by recent invasion of the giant African snail, A. fulica, which began in the 1980s.41,42 As Brazil is currently experiencing the explosive phase of the invasion of A. fulica, which has now been recorded in 25 of the 26 states and in the Federal District (Figure 2), the emergence of eosinophilic meningitis is a matter of concern,41,42 although many species of molluscs may act as intermediate hosts in Brazil.43

Figure 2.

Current distribution of the giant African snail, Achatina fulica, in Brazil, updated from Thiengo, et al.41

Conclusion

The spread of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Brazil is a matter of public health concern because of the widespread occurrence of infected rats and snails in peridomestic areas. There is a need for education of the population regarding disease transmission and prevention. Physicians should be made more aware of the possibility of A. cantonensis infection. And serological diagnosis of angiostrongyliasis should be available to facilitate appropriate medical treatment. Control and monitoring of intermediate and definitive hosts in areas of epidemiological relevance should be undertaken to limit the occurrence of new transmission foci.

Acknowledgements

This paper represents a contribution to the Rat Lungworm Disease Scientific Workshop held at the Ala Moana Hotel, Honolulu, Hawai‘i in August 2011. Funding for the workshop and for this publication was provided by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture, through Award No. 2011-65213-29954.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identifies any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Foronda P, López-González M, Miquel J, et al. Finding of Parastrongylus cantonensis (Chen, 1935) in Rattus rattus in the Canary Islands (Spain) Acta Trop. 2010;114:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross J. Public health importance of Angiostrongylus cantonensis and its relatives. Parasitol Today. 1987;3(12):367–369. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(87)90242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caldeira R, Mendonça C, Gouveia C, et al. First record of molluscs naturally infected with Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Chen, 1935) (Nematoda: Mestastrongylidae) in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102(7):887–889. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007000700018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maldonado A, Jr, Simões R, Oliveira A, et al. First report of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae) in Achatina fulica (Mollusca: Gastropoda) from southeast and south regions of Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2010;105(7):938–941. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762010000700019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drozdz J. Révision de le systématique du genre Angiostrongylus Kamensky, 1905 (Nematoda: Metastrongyloidea) Ann Parasit Hum Comp. 1970;45(5):597–603. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1970455597. (Fre). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lv S, Zang Y, Liu H, et al. Invasive snails and an emerging infectious disease: results from the first national survey on Angiostrongylus cantonensis in China. PLoS Neglect Trop Dis. 2009;3(2):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000368. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson RC. CIH Keys to the Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates. No. 5. Keys to Genera of the Superfamily Metastrongyloidea. Farnham Royal, UK: Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Q-P, Lai D-H, Zhu X-Q, Chen X-G, et al. Human angiostrongyliasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:621–630. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morera P, Céspedes R. Angiostrongylus costaricensis n. sp. (Nematoda: Metastrongylylidae) a new lungworm occurring in Man in Costa Rica. Rev Biol Trop. 1971;18:173–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morera P, Amador J. Prevalencia de la angiostrongiliosis abdominal y la distribución estacional en la precipitación. Rev Costarric Salud Publica. 1998;7:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quirós JL, Jiménez E, Bonilla R, et al. Abdominal angiostrongyliasis with involvement of liver histopathologically confirmed: a case report. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 2011;53(4):219–222. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652011000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dougherty EC. The genus Aelurostrongylus Cameron, 1927 (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae), and its relatives; with descriptions of Parafilaroides gen. nov., and Angiostrongylus gubernaculatus sp. nov. Proc Helm Soc Wash. 1946;13(1):16–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skrjabin KI, Shikhobalova NP, Schulz RS, Popova TI, Boev SN, Delyamure SL. Keys to Parasitic Nematodes, Vol. 3 Strongylata. Leiden: Brill; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamaguti S. Studies on the helminth fauna of Japan. Part 35. Mammalian nematodes II. Japan J Zool. 1941;9(3):409–439. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chabaud AG. Description of Stefankostrongylus dubosti n. sp. parasite of Patomagale and attempt at classification of Angiostrongylinae nematodes. Ann Parasit Hum Comp. 1972;47(5):735–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ubelaker JE. Systematics of species referred to the genus Angiostrongylus. J Parasitol. 1986;72:237–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen HT. Un nouveau nématode pulmonaire, Pulmonema cantonensis n. g., n. sp., des rats de Canton. Ann Parasit Hum Comp. 1935;13:312–370. (Fre). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thiengo SC, Maldonado A, Mota EM, et al. The giant African snail Achatina fulica as natural intermediate host of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Pernambuco, northeast Brazil. Acta Trop. 2010;115:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maldonado A, Simões R, Thiengo SC. Angiostrongyliasis in the Americas. In: Lorenzo-Morales J, editor. Zoonosis. Rijeka: InTech; 2012. pp. 303–320. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng T, Alicata J. On the mode of infection of Achatina fulica by the larvae of Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Malacologia. 1965;2:267–274. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhaibulaya M. Comparative studies on the life history of Angiostrongylus mackerrasae Bhaibulaya, 1968 and Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Chen, 1935) Int J Parasitol. 1975;5:7–20. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(75)90091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graeff-Teixeira C, da Silva ACA, Yoshimura K. Update on eosinophilic meningoencephalitis and its clinical relevance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(2):322–348. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00044-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallace G, Rosen L. Studies on eosinophilic meningitis V. Molluscan hosts of Angiostrongylus cantonensis on Pacific Islands. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;18(2):206–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yousif F, Ibrahim A. The first record of Angiostrongylus cantonensis from Egypt. Z Parasitenkd. 1978;56:73–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00925940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thiengo SC. Mode of infection of Sarasinula marginata (Mollusca) with Angiostrongylus costaricensis larvae (Nematoda) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1996;91(3):277–288. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acha PN, Szyfres B. Zoonosis y Enfermedades Transmisibles Comunes al Hombre y a los Animales. Washington, DC: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lima A, Mesquita S, Santos S, et al. Alicata disease: neuroinfestation by Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil. Arq Neuro-psiquiat. 2009;67(4):1093–1096. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2009000600025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malek E, Cheng T. Medical and Economic Malacology. New York: Academic Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lv S, Zhang Y, Steinmann P, et al. The emergence of angiostrongyliasis in the People's Republic of China: the interplay between invasive snails, climate change and transmission dynamics. Freshw Biol. 2011;56(4):717–734. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pascual JE, Bouli RP, Aguiar H. Eosinophilic meningitis in Cuba, caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30:960–962. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.New D, Little M, Cross J. Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection from eating raw snails. New Engl J Med. 1995;332(16):1105–1106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504203321619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aguiar PH, Morera P, Pascual J. First record of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Cuba. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30(5):963–965. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dorta-Contreras A, Padilla-Docal B, Moreira J, et al. Neuroimmunological findings of Angiostrongylus cantonensis meningitis in Ecuadorian patients. Arq Neuro-psiquiat. 2011;69(3):466–469. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2011000400011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slom T, Johnson S. Eosinophilic meningitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2003;5(4):322–328. doi: 10.1007/s11908-003-0010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pincay T, García L, Narváez E, Decker O, Martini L, Moreira JM. Angiostrongyliasis due to Parastrongylus (Angiostrongylus) cantonensis in Ecuador. First report in South America. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14(suppl 2):37. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raccurt CP, Blaise J, Durette-Desset MC. Présence d'Angiostrongylus cantonensis en Haïti. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8(5):423–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01035.x. (Fre). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ciaravolo RMC, Pinto PLS, Mota DJG. Meningite eosinofílica e a infecção por Angiostrongylus cantonensis: um agravo emergente no Brasil. Vector, Inf Téc Cient, SUCEN-SES-SP. 2010;8:7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreira V, Giese E, Nascimento L, et al. Endemic angiostrongiliase in Brazilian Amazon: a natural parasitism by Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae) in Rattus rattus and R. norvegicus (Rodentia: Muridae) and Achatina fulica (Mollusca: Gastropoda) Acta Trop. 2013;125(1):90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simões R, Monteiro F, Sánchez E, et al. Endemic angiostrongyliasis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(7):1331–1333. doi: 10.3201/eid1707.101822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diaz J. Helminth eosinophilic meningitis: emerging zoonotic diseases in the South. J Louisiana State Med Soc. 2008;160(6):333–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thiengo SC, Faraco FA, Salgado NC, et al. Rapid spread of an invasive snail in South America: the giant African snail, Achatina fulica, in Brasil. Biol Invasions. 2007;9:693–702. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zanol J, Fernandez M, Oliveira A, Russo C, Thiengo S. The exotic invasive snail Achatina fulica (Stylommatophora, Mollusca) in the State of Rio de Janeiro (Brazil): current status. Biota Neotrop. 2010;10(3):447–451. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carvalho OS, Scholte RGC, Mendonça CLF, Passos LKJ, Caldeira RL. Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematode: Metastrongyloidea) in molluscs from harbour areas in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107(6):740–746. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762012000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]