Abstract

Although alpha activity (10 Hz) is by far the strongest signal produced by the human brain, it has for decades been considered to reflect rest or idling. However, recent studies have clearly demonstrated that alpha activity plays a pivotal role for cognitive processing. Gamma oscillations (> 30 Hz) and their role for cognition have also been the subject of intensive research. While gamma activity is thought to reflect functional processing, alpha oscillations are now thought to reflect functional inhibition in order to suppress the processing of distracting information. In our recent magnetoencephalography study we found that both power and phase of posterior alpha oscillations are top-down modulated in order to prevent the incorporation of predictable distracters in working memory. We further discuss these results here. We additionally show that the processing of the distracters is clearly distinguishable from the processing of the items to be remembered. The former induced a weaker gamma power and evoked a higher alpha activity. The higher the evoked alpha activity, the better the efficiency of distracter suppression which also depends on the pre-distracter alpha power and phase adjustment. Altogether, these results emphasize the protecting role of alpha activity and its remarkable flexibility. This ability to inhibit distracter information is crucial in our complex environment, as illustrated by the difficulties encountered by patients suffering from attentional disorders.

Keywords: alpha, attention, distracter, electroencephalography (EEG), executive control, gamma, magnetoencephalography (MEG), oscillations, synchronization, working memory

Alpha activity has for decades been considered as a global signal reflecting cortical idling. This view has been challenged in recent years and has been supplanted by the idea that alpha activity plays a role in filtering incoming information. Covert attention tasks have provided the first evidence for this hypothesis. For instance, when participants covertly attend to the right hemifield, the left visual system is engaged and exhibits a relative decrease of alpha activity while an increase of alpha power is observed in the unengaged right hemisphere.1-4 Furthermore, several experiment have shown that high alpha power over task-irrelevant regions is important for the participants to perform optimally.5,6 Combined EEG and fMRI recordings have further showed that the Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) signal is negatively correlated with alpha activity.7,8 Even more direct evidence arises from monkey recordings in the somatosensory system, showing a negative relation between alpha power and spiking rate.9 Finally, in line with its rhythmical nature, the level of excitability differs in the different phases of the alpha cycle. More specifically, the spiking and gamma (> 30 Hz) activities, as well as the visual perception and the probability of seeing a phosphene following a TMS stimulation over the posterior cortex, have been shown to be modulated by the phase of the alpha cycle.9-15 This phasic modulation, taken together with the inhibitory role of alpha activity, suggests a mechanism of ‘pulsed inhibition’ in which the transmission of sensory input would be suppressed during parts of the alpha cycle.16-18

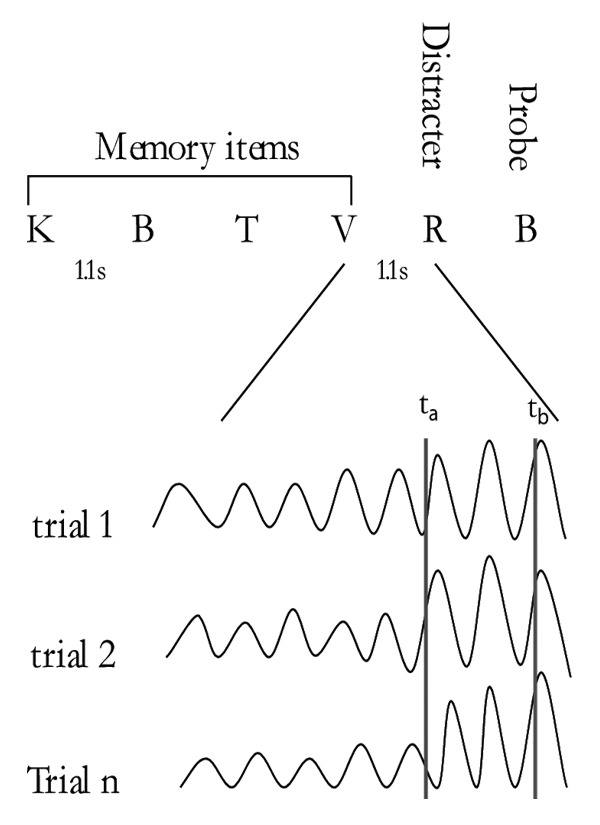

In our recent magnetoencephalography (MEG) experiment, we further investigated the protective properties of alpha activity. We more specifically aimed at determining whether both alpha power and phase can adjust to suppress predictable (in time) distracting information in a modified Sternberg working memory task. In each trial, participants had to encode four letters and then determine whether the probe was similar to one of these letters. A distracter was presented during the retention interval, always at 1.1s after the last memory item. We found that posterior alpha power increases in anticipation of incoming distracters. Furthermore, the higher the alpha power before the distracter, the better the working memory performance. Strikingly, the alpha phase also adjusted prior to the distracter - and a failure to adjust impaired performance19 (see Fig. 1 for a summary of these results).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the key findings. A set of 4 memory items were presented sequentially. Subjects had to indicate if the probe was on the list (yes/no). In the retention interval an intruding distracter was presented always at the same time. We investigated the oscillatory activity in anticipation of the distracter. Finding 1: The alpha activity adjusted in phase just prior to the onset of the distracter (compare the phases ta and tb). In trials where the alpha phase did not adjust, the response times to the probes were longer. Finding 2: The alpha activity increased in anticipation of the distracter. In trials where the alpha activity increased less, the response times to the probes were longer. Conclusion: Both power and phase of the ongoing alpha oscillations adjust in anticipation of distracters. A failure to adjust the alpha activity, results in an incorporation of distracters in working memory and thus reduced memory performance. This adjustment must be a consequence of a temporally specific top-down drive to posterior perceptual regions.

These results strongly emphasized the functional importance of alpha activity. In situations where distracting information can be anticipated, alpha power and phase are adjusted in order to ‘close the door’ of the visual systems just on time. In a previous study, the opposite mechanism has been found for posterior alpha power, i.e., a decrease, in anticipation of a relevant stimulus.20 We further found that alpha activity over the prefrontal cortex, more specifically the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, was coherent with the alpha activity over the posterior cortex. The implication is that the prefrontal cortex exerts top-down control of sensory regions by means of long-distance synchronization in the alpha band. Such mechanism has been identified in a recent monkey study. In an attention task it was demonstrated that two visual areas became phase-synchronized in the alpha band. Further, this synchronization was orchestrated by the pulvinar.21 Possibly, the anticipatory phase-adjustment we observe is controlled by similar top-down mechanisms.

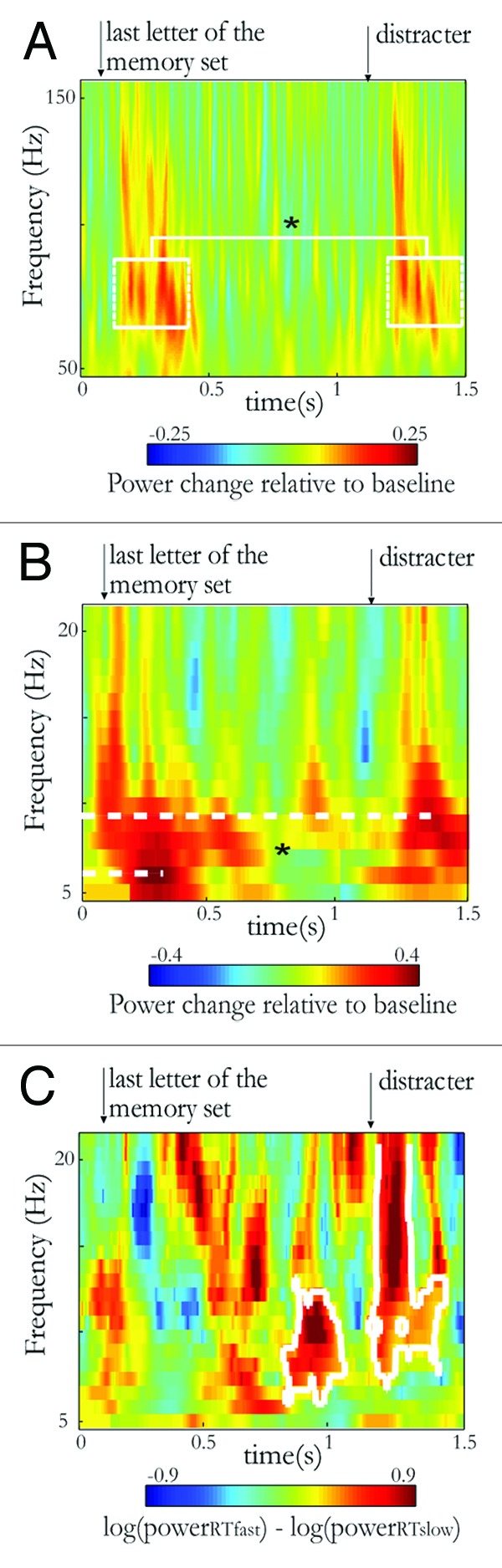

How the suppression of the processing of the distracter is then expressed? We further investigated the activity induced and evoked by the distracter in the occipito-temporal cortex (data not shown in Bonnefond and Jensen19). We found that the gamma activity (60–90 Hz) induced by the distracter presentation was weaker than the gamma activity induced by the last memory item (see Fig. 2A). This is in line with the studies showing that gamma activity (> 30 Hz) reflects active processing of a stimulus and is modulated by attention.22,23 However, although we previously showed that fast reaction times trials exhibit a stronger alpha power and phase adjustment prior to the distracter,19 the difference in the distracter-induced gamma power between these two types of trials did not reach significance level (p = 0.2) probably due to a weak signal to noise ratio (only 30 trials in each condition).

Figure 2. Functional signature of the distracter processing in the left occipitotemporal region of interest (see ref. 19). (A) Time-frequency representation of the gamma activity induced by the last memory item and the strong distracter. The gamma induced (60–90 Hz; 0.1–0.4 sec post-stimulus) by the distracter was weaker than the gamma induced by the last memory item (p < 0.05 as indicated by the *). For the purpose of visualization, the gamma observed here is baseline corrected (100 ms interval before the last memory item). The statistics have however been conducted on induced gamma activity not using a baseline. The arrows indicate the onset of the last memory item and of the distracter. (B) Time-frequency representation of the activity evoked by the last memory item and the strong distracter (baseline: 100 ms interval before the last memory item). The frequency peak of the evoked activity is significantly higher (9Hz vs. 5Hz) for the distracter than for the last memory item (p < 0.05 as indicated by the *). (C) Time-frequency representation of the evoked activity when comparing fast and slow reaction times trials in the strong distracter condition. The white contour indicates the significant clusters obtained using a cluster-based non-parametric randomization.25 Two clusters were found, the first one illustrates the higher adjusted alpha activity found for fast reaction times trials in Bonnefond and Jensen’s paper19 (see also B showing pre-distracter alpha activity). The second one further reflects a higher evoked alpha activity (including a very short burst of higher frequency activity).

The difference in alpha power induced by the distracter and the memory item was not significant. However, we observed a clear difference in the activity evoked by the memory item and the distracter. The frequency peak was in the theta band around 5 Hz for the memory item while the peak was around 9 Hz, i.e., in the alpha band, for the distracter (see Fig. 2B). Moreover, alpha activity evoked by the distracter was stronger for trials with good performance (i.e., with fast reaction times to the probe; see Figs. 2C and 4B of Bonnefond and Jensen19). In future experiments, one could compare processing of predictable vs. non predictable distracters to determine whether the distracter-evoked activity observed here is generalizable to non-predictable distracters.

To conclude, we emphasized the functional inhibition role of alpha activity during anticipation and processing of a distracter. Without such a mechanism we would not be able to operate in a natural environment where distracting information needs to be ignored. Such difficulties are found in patients suffering from attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Investigating the dynamics of alpha activity in the kind of tasks we used in such patients might provide insight into the neuronal substrate of attentional disorders.

In addition, gamma activity seems to reflect the level of processing of the stimulus, being lower when the participant ignores the stimulus presented. We suggest that alpha activity reflects anticipative top-down modulation of excitability in posterior areas while gamma power reflects the interaction between this top-down modulation and the stimulus-driven activity. This interaction could be revealed by a cross-frequency coupling between the alpha phase and the gamma power. This question will be addressed in future experiments. The other burning question that needs to be addressed regards to what extent the mechanism of phase adjustment is general, i.e., whether it is expressed in other areas than visual areas and by other oscillation frequencies.24 Finally, it is essential to further investigate the mechanism behind the top-down control of (posterior) alpha activity in order to understand (1) its role in the routing of information by shutting down irrelevant areas16 and (2) how it operates (e.g., involvement of the thalamus21).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cib/article/22702

References

- 1.Rihs TA, Michel CM, Thut G. Mechanisms of selective inhibition in visual spatial attention are indexed by alpha-band EEG synchronization. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:603–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rihs TA, Michel CM, Thut G. A bias for posterior alpha-band power suppression versus enhancement during shifting versus maintenance of spatial attention. Neuroimage. 2009;44:190–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Worden MS, Foxe JJ, Wang N, Simpson GV. Anticipatory biasing of visuospatial attention indexed by retinotopically specific alpha-band electroencephalography increases over occipital cortex. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-j0002.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foxe JJ, Simpson GV, Ahlfors SP. Parieto-occipital approximately 10 Hz activity reflects anticipatory state of visual attention mechanisms. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3929–33. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199812010-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haegens S, Luther L, Jensen O. Somatosensory anticipatory alpha activity increases to suppress distracting input. J Cogn Neurosci. 2012;24:677–85. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Händel BF, Haarmeier T, Jensen O. Alpha oscillations correlate with the successful inhibition of unattended stimuli. J Cogn Neurosci. 2011;23:2494–502. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheeringa R, Petersson KM, Oostenveld R, Norris DG, Hagoort P, Bastiaansen MC. Trial-by-trial coupling between EEG and BOLD identifies networks related to alpha and theta EEG power increases during working memory maintenance. Neuroimage. 2009;44:1224–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laufs H, Holt JL, Elfont R, Krams M, Paul JS, Krakow K, et al. Where the BOLD signal goes when alpha EEG leaves. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1408–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haegens S, Nácher V, Luna R, Romo R, Jensen O. alpha-Oscillations in the monkey sensorimotor network influence discrimination performance by rhythmical inhibition of neuronal spiking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19377–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117190108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osipova D, Hermes D, Jensen O. Gamma power is phase-locked to posterior alpha activity. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spaak E, Bonnefond M, Maier A, Leopold D, Jensen O. Layer-specific entrainment of gamma-band neural activity by the alpha rhythm in monkey visual cortex. Curr Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.020. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dugué L, Marque P, VanRullen R. The phase of ongoing oscillations mediates the causal relation between brain excitation and visual perception. J Neurosci. 2011;31:11889–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1161-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathewson KE, Gratton G, Fabiani M, Beck DM, Ro T. To see or not to see: prestimulus alpha phase predicts visual awareness. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2725–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3963-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Busch NA, VanRullen R. Spontaneous EEG oscillations reveal periodic sampling of visual attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16048–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004801107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romei V, Gross J, Thut G. Sounds reset rhythms of visual cortex and corresponding human visual perception. Curr Biol. 2012;22:807–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen O, Mazaheri A. Shaping functional architecture by oscillatory alpha activity: gating by inhibition. Front Hum Neurosci. 2010;4:186. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klimesch W, Sauseng P, Hanslmayr S. EEG alpha oscillations: the inhibition-timing hypothesis. Brain Res Rev. 2007;53:63–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen O, Bonnefond M, VanRullen R. An oscillatory mechanism for prioritizing salient unattended stimuli. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16:200–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonnefond M, Jensen O. Alpha Oscillations Serve to Protect Working Memory Maintenance against Anticipated Distracters. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1969–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rohenkohl G, Nobre AC. alpha oscillations related to anticipatory attention follow temporal expectations. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14076–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3387-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saalmann YB, Pinsk MA, Wang L, Li X, Kastner S. The pulvinar regulates information transmission between cortical areas based on attention demands. Science. 2012;337:753–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1223082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fries P, Reynolds JH, Rorie AE, Desimone R. Modulation of oscillatory neuronal synchronization by selective visual attention. Science. 2001;291:1560–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1055465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen O, Kaiser J, Lachaux JP. Human gamma-frequency oscillations associated with attention and memory. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:317–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lakatos P, Karmos G, Mehta AD, Ulbert I, Schroeder CE. Entrainment of neuronal oscillations as a mechanism of attentional selection. Science. 2008;320:110–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1154735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maris E, Oostenveld R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;164:177–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]