Abstract

We assessed the pharmacokinetics (PK), tolerability and safety of tariquidar (TQD), a P-glycoprotein (Pgp) inhibitor, after i.v. administration of single ascending doses. Employed doses were up to 4-fold higher than in previous clinical trials in cancer patients and are capable to inhibit Pgp at the blood-brain barrier (BBB). 15 male healthy volunteers were randomised to receive single i.v. doses of TQD at 4, 6 or 8 mg/kg body weight and underwent blood sampling over 24 h. TQD concentrations were determined in plasma samples with high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. No dose limiting toxicities of TQD were observed. Area under the plasma concentration-time curve from start until 24 h after end of infusion (AUC0-n) was positively correlated with administered TQD dose (r=0.8981, p<0.0001). Moreover, we found a positive correlation for volume of distribution at steady state Vss (r=0.7129, p=0.0004) with TQD dose. Dose dependency of Vss points to non-linear PK of TQD, which was in all likelihood caused by transporter saturation at high TQD doses. Acceptable safety and tolerability and dose-linear increases in plasma exposure support future use of TQD at doses up to 8 mg/kg to inhibit Pgp at the human BBB.

Keywords: tariquidar, XR9576, non-linear pharmacokinetics, P-glycoprotein, stability, blood-brain barrier

Introduction

The adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding cassette (ABC) transporter P-glycoprotein (Pgp, ABCB1) is expressed in the luminal membranes of the small intestine and blood-brain barrier (BBB) or the apical membranes of excretory cells such as hepatocytes and kidney proximal tubule epithelia [1]. Pgp actively transports a wide range of structurally diverse, mostly lipophilic compounds against concentration gradients and thereby exerts a considerable impact on drug absorption, distribution and excretion. A multitude of studies have linked increased expression of Pgp in tumours to impaired chemotherapy response and lower patient survival [2]. In addition, disease-related increases in activity of Pgp at the BBB probably contribute to therapy refractoriness in neurological diseases like epilepsy and depression by impeding the accumulation of therapeutically effective drug concentrations in tissue targeted for treatment [3].

For over two decades, efforts to inhibit Pgp to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer have been made [4-6]. In early clinical trials first-generation Pgp inhibitors, such as verapamil and cyclosporine A were used, which were toxic at concentrations needed to inhibit Pgp. Second-generation Pgp inhibitors such as valspodar (PSC 833) and biricodar (VX-710) were more potent and less toxic than first-generation Pgp inhibitors. Unfortunately, drug-drug interactions, involving cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) inhibition, were leading to increased systemic exposure and hence elevated toxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs [6]. These limitations led to the development of more potent and specific third-generation Pgp inhibitors including tariquidar (XR9576, TQD), elacridar (GF120918), zosuquidar (LY335979), laniquidar (R101933), and ONT-093 [7-11].

Until now clinical pharmacokinetic (PK) data of TQD are available for doses administered intravenously (i.v.) up to 2 mg/kg body weight (BW). Linear dose dependent increases of the area under the curve (AUC) and the peak serum TQD concentration (Cmax) between 0.1 to 2 mg/kg were reported [4, 7]. The 2 mg/kg dose has been chosen for clinical trials with TQD in cancer patients as this dose was shown to fully inhibit Pgp-mediated rhodamine 123 efflux from CD56-positive lymphocytes, which was used as a surrogate marker of Pgp inhibition occurring in vivo [4, 7]. However, in contrast to the inhibition of Pgp-mediated rhodamine 123 efflux from CD56-positive lymphocytes, the half-maximum effect concentration (EC50) for functional inhibition of Pgp at the human BBB was found to be several times higher (669 nM vs. 33 nM) suggesting that Pgp at the BBB is more resistant to inhibition than Pgp in peripheral organs [7, 12]. Consequently, higher TQD doses than 2 mg/kg will be needed to effectively block Pgp at the human BBB.

Higher doses of TQD (up to 8 mg/kg) were recently investigated in vivo in clinical positron emission tomography (PET) imaging studies with Pgp substrate radiotracers [12, 13]. Pgp substrate penetration into the brain, as a measure of pharmacodynamic response, was found to increase as a function of administered TQD dose.[12, 13] The present study describes concomitant PK of TQD administered at doses between 4 and 8 mg/kg, which is considered being mandatory for further pharmacodynamic studies with high doses of this compound. Since the stability of TQD in human plasma is unknown, a separate in vitro experiment was performed to investigate stability over time at different storage conditions.

Methods

Study population

The present study was conducted at the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna. The study was approved by the local Independent Ethics Committee and the National Competent Authority (BASG/AGES), and performed in accordance with guidelines established by the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. All subjects were given a detailed verbal and written description of the study and their written consent was obtained prior to the enrolment into the study.

Healthy volunteers underwent a normal physical examination with no clinical significant findings in vital signs, laboratory values and electrocardiogram results as considered by the investigator. Subjects were not enrolled in the study if they had participated in a clinical study with an investigational drug one month or had taken any medication within two weeks prior to the study day. Subjects, who had donated blood or plasma within 3 months prior to the first visit, as well as those with a significant medical history and history of drug or alcohol abuse, were also excluded.

15 young male subjects were randomised into the three dose groups. Data were acquired align with a previously published PET study [12]. Furthermore data from a pilot study in which subjects had received 2 mg/kg BW TQD are shown for comparison [14].

Study design and treatment

The study was designed as a single dose escalation study with administration of TQD at 4, 6, and 8 mg/kg BW. 10-ml vials of TQD for i.v. infusion containing 7.5 mg/ml of TQD free base in 20% ethanol/80% propylene glycol were provided by AzaTrius Pharmaceuticals Pvt. Ltd. (London, UK). Following a recently described procedure, [12] TQD was freshly diluted in 5% (w/v) aqueous dextrose solution to a fixed concentration of 0.6 mg/ml and infused i.v. at a rate of 375 ml/h until achieving the target dose. This procedure differs from the 2 mg/kg dose group in which fixed infusion duration of 0.5 h was applied [14]. Blood samples were collected in tubes containing sodium heparin as an anticoagulant at pre-dose, at time points of 25%, 50% and 75% of the infusion duration, at the end of the infusion, and at 5, 10, 20, 30, 60, 120, and 1440 min after the end of the infusion. Immediately after blood drawing, samples were stored on crashed ice until centrifugation, after which plasma was frozen at −20°C within 30 min. At the end of each study day the samples were transferred to a −80°C freezer.

Safety and tolerability

All subjects were confined to the clinical ward under continuous medical observation until 24 h after the end of the TQD infusion. Clinical safety monitoring included repeated recording of blood pressure, heart rate and ECG data for the first 24 h post-dosing, clinical chemistry, coagulation and haematology, assessments of adverse events (AE) and their follow up completion. Final visits for physical examination, vital sign and AE check as well as blood and urine analysis were scheduled within one week after the study day.

Plasma pharmacokinetic analysis

The concentrations of TQD in plasma were measured with high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) using a Dionex UltiMate 3000 system (Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) connected with an API 4000 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Concord, Ontario, Canada). After addition of 200 μl of methanol to 100 μl of plasma, the samples were centrifuged (5,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C) and 80 μl of the clear supernatant was injected onto the HPLC column. Separation of TQD was carried out at 35°C using a Hypersil BDS-C18 column (5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm I.D., Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc, Waltham, MA, USA) preceded by a Hypersil BDS-C18 pre-column (5 μm, 10 × 4.6 mm I.D.). The mobile phase consisted of a continuous linear gradient, mixed from 10 mM aqueous ammonium acetate/acetic acid buffer, pH 5.0 and methanol. Linear calibration curves were generated by spiking drug-free plasma with standard solutions of TQD (final concentrations ranging from 0.005 to 5 μg/ml). The lower limit of detection of TQD was 3 ng/ml and the lower limit of quantification 5 ng/ml.

Pharmacokinetic calculations and statistical analysis

Maximal TQD concentration in plasma (Cmax) and time at maximal concentration (tmax) were recorded directly from experimental observations. PK parameters area under the curve from start until 24 h after the end of the infusion (AUC0-n), volume of distribution at steady state (VSS), clearance (CL), and terminal elimination half-life time (t½) were calculated by using the Kinetica 2000 software package, version 3.0 (InnaPhase, PA, USA). The relationship between the PK variables AUC0-n and VSS and the administered dose was determined using linear regression. We included the data from our pilot study [14] for linear fitting to consistently connect our new high dose PK data with those from the literature. Origin, version 7 (OriginLab Corporation, MA, USA), was used for linear regression and statistical computations. The level of significance was set to p<0.05.

Stability study

The stability of TQD in plasma was examined at three different concentrations (0.1, 0.5 and 2.0 μg/ml TQD). Each stock solution was subdivided into 16 separate aliquots. The first 4 aliquots were immediately analysed by HPLC. The TQD concentrations obtained from this quantification were considered as baseline concentrations for subsequent long-term quantifications. The 12 remaining aliquots were stored for 24 h, 1 month and for 3 months, respectively, at 4 different temperature levels, i.e. room temperature (RT), 4°C, −20°C, and −80°C. Subsequently, these aliquots were used for measuring TQD concentrations after the specified time intervals. The default criterion for TQD stability was set to 95%.

Results

Demografics

In the present study all participants were male, 14 Caucasians and one Hispanic. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) of age and weight for the 4, 6 and 8 mg/kg dose groups were 36.3±11.2, 29.9±8.3 and 31.4±6.0 years and 84.6±7.8, 88.4±13.2 and 74.4±8.4 kg, respectively.

Safety and tolerability

The study medication was generally well tolerated and no serious or severe AEs were observed. Overall four cases of hematoma and one case of phlebitis due to cannulation as well as five cases of metallic taste in the mouth occurred. Other adverse drug effects to TQD were vertigo (two), bradycardia (one) and headache (one). Heart rate, blood pressure as well as ECG did not significantly change during and after TQD administration. No subject had any significant change in blood chemistries (including electrolytes, liver and renal function tests), complete blood count and coagulation over the whole study period. No volunteer discontinued prematurely the study. In the case of the last subject, for safety reasons the infusion was stopped 20 min before the scheduled end due to moderate orthostatic hypotension and vertigo. This AE did not influence any other study related procedures.

Pharmacokinetics

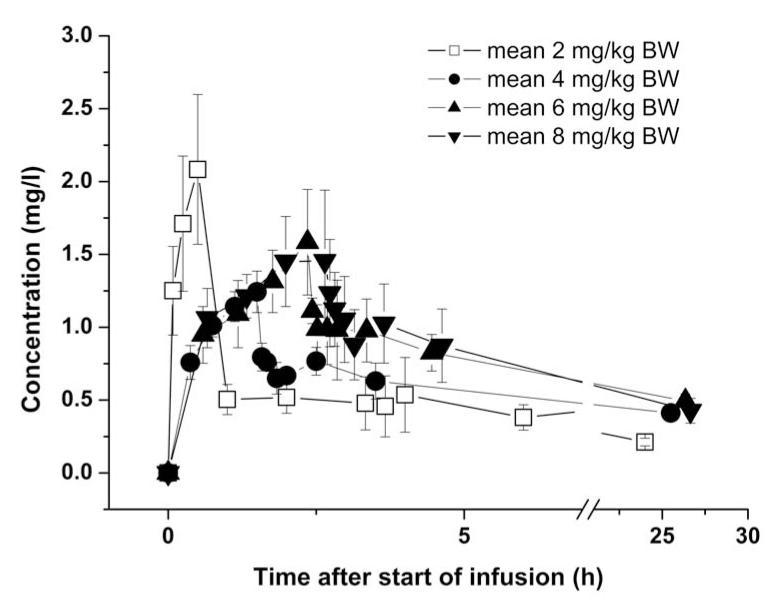

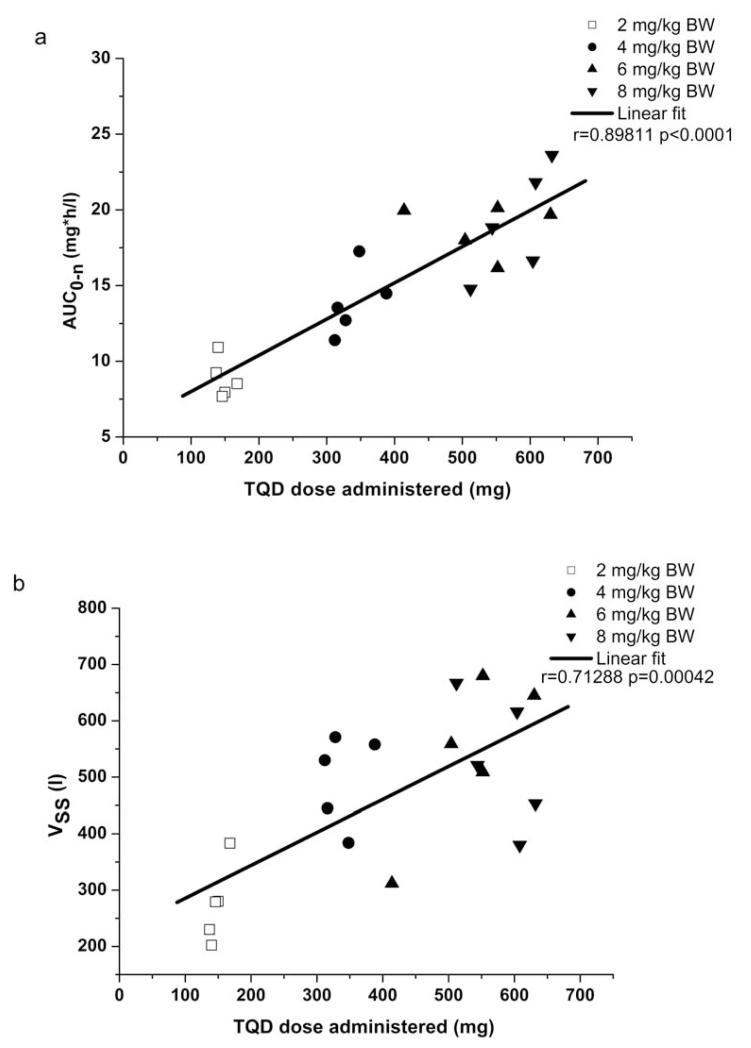

The clinical part of the study was completed within one month. Plasma samples were stored at −80°C for 4 to 5 months until analysis. Mean plasma concentration-time curves of TQD are depicted in fig. 1. In all plasma samples the concentration of possible metabolites was below the detection limit. Mean infusion duration was 1.50±0.14 h for the 4 mg/kg, 2.35±0.35 h for the 6 mg/kg and 2.58±0.22 h for the 8 mg/kg dose group. For the respective dose groups, the mean administered TQD dose was 338±31 mg, 530±79 mg and 580±50 mg. Individual PK parameters are presented in table 1. There was a statistically significant positive correlation between injected dose and the PK parameters AUC0-n (coefficient of correlation r=0.8981, p<0.0001) and VSS (r=0.7129, p=0.0004) (fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Mean (±SD) concentration-time curves of TQD in plasma for the 4, 6 and 8 mg/kg dose groups (n=5 per dose group). For comparison, previously published data from a 2 mg/kg dose group (n=5) is also shown [14].

Table 1. Individual pharmacokinetic parameters of TQD after single dose administration at doses of 4, 6 and 8 mg/kg BW (n=5 per dose group).

| Dose group (mg/kg BW) |

Subject number |

Infusion duration (h) |

Dose (mg) |

Cmax (mg/l) |

tmax(h) | AUC0-n (mg*h/l) |

CL (l/h) | t½(h) | Vss (l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 1 | 1.72 | 388 | 1.31 | 1.29 | 14.48 | 9.27 | 43 | 558 |

| 4 | 2 | 1.38 | 312 | 1.21 | 1.38 | 11.39 | 11.29 | 33 | 530 |

| 4 | 3 | 1.45 | 328 | 1.12 | 1.45 | 12.71 | 7.39 | 55 | 571 |

| 4 | 4 | 1.55 | 348 | 1.47 | 1.55 | 17.26 | 9.22 | 30 | 384 |

| 4 | 5 | 1.40 | 316 | 1.13 | 1.40 | 13.54 | 10.11 | 31 | 445 |

| 6 | 6 | 1.83 | 414 | 2.03 | 1.83 | 19.96 | 13.53 | 16 | 312 |

| 6 | 7 | 2.23 | 504 | 1.81 | 2.23 | 18.00 | 11.35 | 35 | 559 |

| 6 | 8 | 2.80 | 630 | 1.13 | 2.80 | 19.68 | 13.56 | 34 | 645 |

| 6 | 9 | 2.45 | 552 | 1.64 | 2.45 | 20.12 | 13.99 | 26 | 509 |

| 6 | 10 | 2.45 | 552 | 1.31 | 2.45 | 16.16 | 15.15 | 33 | 680 |

| 8 | 11 | 2.82 | 632 | 1.59 | 2.82 | 23.61 | 15.71 | 21 | 453 |

| 8 | 12 | 2.42 | 544 | 1.92 | 2.42 | 18.83 | 15.41 | 25 | 521 |

| 8 | 13 | 2.28 | 512 | 1.05 | 2.28 | 14.77 | 16.21 | 30 | 667 |

| 8 | 14 | 2.70 | 608 | 1.87 | 2.70 | 21.81 | 20.85 | 14 | 380 |

| 8 | 15 | 2.67 | 604 | 1.66 | 2.26 | 16.64 | 22.15 | 21 | 616 |

Fig. 2.

Scatter plots and linear regression of the pharmacokinetic parameters AUC0-n (a) and VSS (b) versus the administered dose. For comparison, the 2 mg/kg dose group data, depicted as open squares, is also shown [14].

Stability

In table 2 the results of the stability study are shown with TQD concentration values displayed as absolute and percent values relative to baseline concentrations. Applying the pre-specified default criterion for TQD stability (i.e., 95%), TQD was stable for 24 h at RT, 4°C, −20°C, and −80°C, respectively. Any longer storage resulted in pronounced degradation, even at −80°C.

Table 2. Stability of TQD in plasma over time at different concentrations and different storage temperatures.

| Concentration | Storage | 24 h | 1 month | 3 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 μg/ml | RT | 0.10±0.004 (100) |

0.008±0.000 (8.6) |

0.003±0.000 (3.0) |

| 4°C | 0.099±0.003 (99) |

0.007±0.001 (7.2) |

0.003±0.000 (3.1) |

|

| −20°C | 0.10±0.002 (100) |

0.073±0.005 (73.9) |

0.041±0.004 (40.8) |

|

| −80°C | 0.098±0.003 (98) |

0.078±0.006 (78.1) |

0.069±0.005 (69.1) |

|

| 0.5 μg/ml | RT | 0.49±0.033 (98) |

0.037±0.002 (9.8) |

0.008±0.001 (1.7) |

| 4°C | 0.51±0.023 (102) |

0.056±0.003 (11.2) |

0.017±0.001 (3.4) |

|

| −20°C | 0.49±0.014 (99) |

0.38±0.021 (77.6) |

0.18±0.014 (36.4) |

|

| −80°C | 0.50±0.025 (100) |

0.41±0.030 (82.3) |

0.27±0.023 (53.9) |

|

| 2.0 μg/ml | RT | 2.02±0.081 (101) |

0.18±0.003 (9.1) |

0.054±0.004 (2.8) |

| 4°C | 1.97±0.050 (98.5) |

0.19±0.004 (9.5) |

0.11±0.006 (5.6) |

|

| −20°C | 1.98±0.075 (99) |

1.51±0.065 (75.8) |

0.97±0.084 (48.3) |

|

| −80°C | 2.01 ±0.064 (100.5) |

1.62±0.068 (80.6) |

1.23±0.056 (61.5) |

Data are expressed as mean (±SD) concentration (μg/ml) of four separate determinations. Values in parentheses represent percent of baseline values. RT: room temperature.

Discussion

In the present study, we describe for the first time the PK of the potent and selective third-generation Pgp inhibitor TQD in healthy volunteers after i.v. administration of doses which were up to 4 times higher than those previously used in clinical trials with this drug in cancer patients (2 mg/kg) [4]. Higher TQD doses than 2 mg/kg are required to achieve effective inhibition of Pgp at the human BBB, [12, 13] which could find future therapeutic application to enhance brain penetration of anticancer or antiepileptic drugs [15, 16]. It has been for instance shown that brain distribution of several tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g. gefitinib, sorafenib, dasatinib, sunitinib, lapatinib) is restricted by transporter-mediated efflux transport at the BBB, [15] suggesting that their efficacy might be improved when co-administered with a Pgp modulator. A previously conducted clinical PET study, in which brain penetration of the radiolabelled model Pgp substrate (R)-[11C]verapamil was assessed in healthy subjects as a surrogate marker of cerebral Pgp activity, had shown that at a TQD dose of 8 mg/kg complete inhibition of Pgp at the human BBB was achieved as reflected by a plateau in the concentration-response curve of TQD [12]. For the 2 mg/kg TQD dose, (R)-[11C]verapamil brain distribution was only 1.25-fold enhanced as compared with baseline scans without TQD administration whereas for the 8 mg/kg TQD dose a 3-fold increase in (R)-[11C]verapamil brain distribution was observed [12]. Choo and colleagues reported that the half-maximum effect dose (ED50) of TQD to enhance the brain-to-plasma ratio of the Pgp substrate loperamide in mice was approximately 4 times higher than the ED50 for increasing the testis-to-plasma ratio suggesting that cerebral Pgp is less amenable to inhibition as compared with Pgp in peripheral organs [17]. Based on these data it can be assumed that in our study Pgp was fully inhibited at the highest employed TQD dose (8 mg/kg), not only at the BBB but also in peripheral organs (e.g. liver, kidneys). There is evidence from previous studies that apart from being a potent inhibitor of Pgp, TQD is also transported at low concentrations by Pgp and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) [18-20]. Thus this study provided us with the unique opportunity to assess the PK of a Pgp/BCRP substrate drug after i.v. administration over a dose range which most likely induced full inhibition of Pgp in all organs. As expected, this clearly resulted in non-linearity of TQD PK, i.e. Vss increased as a function of administered dose (fig. 2b). Vss was up to 3 times higher for the 8 mg/kg TQD dose as compared with the 2 mg/kg dose. This could be due to increasing inhibition of Pgp in different tissues protected by Pgp with increasing TQD doses leading to enhanced distribution of the Pgp substrate TQD from plasma into these tissues. This assumption is supported by findings from a previous preclinical study, in which it was shown that the brain-to-plasma concentration ratio of TQD in rats (a measure of drug distribution to brain) was approximately three times higher after administration of a high dose of TQD (15 mg/kg) as compared with a microdose (0.002 mg/kg) [18]. Similar results were recently reported for the Pgp modulator elacridar, for which brain distribution in rats or mice was found to be dependent of elacridar plasma concentration levels, [21-23] suggesting that at high plasma concentrations Pgp at the BBB was inhibited leading to increased brain exposure to elacridar. The dose dependency of Vss of TQD has not been reported in a previous dose escalation study up to a maximum dose of 2 mg/kg [7].

In our study, TQD plasma concentration-time profiles were characterised by a fast initial and subsequent flattened increase until the end of the infusion (fig. 1). This observation might also be related to the ability of TQD to distribute extensively from the vascular system into tissues, possibly by inhibition of transporter-mediated efflux processes at higher concentrations. After the end of the infusion a rapid decrease in plasma TQD concentrations was followed by a secondary peaking within the first few hours (fig. 1), which might be a consequence of enterohepatic circulation of TQD. Concentrations of TQD in plasma within individual dose groups were found to be quite variable despite traditional dose calculation based on mg/kg BW and parenteral administration (table 1). This has also been observed in previous studies [12, 14]. Such a high variability in plasma concentration has also been described for other Pgp inhibitors, such as elacridar, [10, 24] valspodar [25] and zosuquidar [26], and might be caused by distribution into deep compartments such as muscle, kidney, liver and pancreas and/or variability in oral absorption rate due to the high lipophilicity of these compounds. Interestingly, we could not detect any metabolites in plasma samples indicating that TQD biotransformation in humans is negligible.

Despite the pronounced dose dependency of Vss (fig. 2b), plasma exposure to TQD, i.e. AUC0-n, was found to largely increase linearly with increasing doses over the dose range from 2 to 8 mg/kg (fig. 2a). This stands in contrast with the Pgp inhibitors zosuquidar and laniquidar, for which greater than proportional increases in AUC had been found with increasing dose [8, 9].

Importantly TQD at doses up to 8 mg/kg BW was generally well tolerated with no particular safety concerns occurring in our study. Although the majority of subjects reported at least one AE, no serious or severe AEs were reported. It cannot be excluded that the most common AE, metallic taste in the mouth, was related to propylene glycol used as co-solvent for the TQD injection solution [13]. In one case, shortly before the scheduled end of the TQD infusion, the administration was prematurely stopped as the subject reported orthostatic hypotension and vertigo. Both symptoms receded rapidly after de-challenging the infusion. Taken together no dose limiting toxicities at Cmax values ranging from 1.05 to 2.03 mg/l were seen. The good tolerability of TQD at doses up to 8 mg/kg is important as it supports the future clinical use of TQD at doses >2 mg/kg for inhibition of Pgp at the BBB. However, clearly for such a future application an oral administration mode would be preferred over the currently employed i.v. route. A particular disadvantage of i.v. dosing is the long infusion duration (up to 3 h for the 8 mg/kg dose), which was necessary to keep, for safety reasons, the percentage of co-solvent in the infusion solution <14% to avoid haemolysis as side effect. We describe for the first time stability of TQD in plasma under different controlled storage conditions (table 2). TQD was found to be stable for 24 h at RT, 4°C, −20°C, and −80°C, respectively. However, after one month of storage at RT or at 4°C the concentrations had degraded to only approximately 10% of the original concentration. More important, even when stored at −20°C TQD concentration after one month decreased to 74-78% and at −80°C to 78-82% of the original values. No concentration dependency was seen for the degradation rate of TQD. It is noteworthy that the instability of TQD in plasma was not mentioned in a previously published report which examined the PK of TQD in human subjects [7].

The pronounced degradation of TQD in plasma over time resulting in lower concentrations than actually present at time of sampling might be considered as most important limitation of the present study. However, as both sample collection and analysis of plasma samples were performed within relatively short time frames, total storage times of individual samples until analysis were overall similar justifying a relative comparison of PK parameters between different dose groups. This is further supported by our observation that degradation of TQD in plasma appeared to be independent of concentration (table 2). As second limitation, the data of the 4, 6 and 8 mg/kg dose groups can only partially be compared with the previously described 2 mg/kg dose group [14] due to modification in the administration scheme. The approach of using a fixed stock solution for TQD dose escalation was used to avoid excess in propylene glycol concentrations of the infusion solution for high TQD dose groups [13]. This change in administration scheme leads to different infusion durations and may therefore hamper the comparability of Cmax values among dose groups.

In conclusion, our results extend previous findings by showing linear plasma exposure to TQD administered i.v. at doses up to 8 mg/kg BW [4]. High dose administration of TQD seems acceptable from the safety point of view which is a prerequisite for future use of this drug to enhance brain penetration of Pgp substrate drugs. Due to instability of TQD in plasma, analytics should be performed as fast as possible. Storage times of plasma samples containing TQD should be accurately recorded and published.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure Statement

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement number 201380 (“Euripides”) and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) project “Transmembrane Transporters in Health and Disease” (SFB F35).

References

- 1.Giacomini KM, Huang SM, Tweedie DJ, Benet LZ, Brouwer KL, Chu X, Dahlin A, Evers R, Fischer V, Hillgren KM, Hoffmaster KA, Ishikawa T, Keppler D, Kim RB, Lee CA, Niemi M, Polli JW, Sugiyama Y, Swaan PW, Ware JA, Wright SH, Yee SW, Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Zhang L. Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:215–236. doi: 10.1038/nrd3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tiwari AK, Sodani K, Dai CL, Ashby CR, Jr., Chen ZS. Revisiting the ABCs of multidrug resistance in cancer chemotherapy. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12:570–594. doi: 10.2174/138920111795164048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Löscher W, Potschka H. Drug resistance in brain diseases and the role of drug efflux transporters. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:591–602. doi: 10.1038/nrn1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox E, Bates SE. Tariquidar (XR9576): a P-glycoprotein drug efflux pump inhibitor. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:447–459. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottesman MM, Fojo T, Bates SE. Multidrug resistance in cancer: Role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:48–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szakacs G, Paterson JK, Ludwig JA, Booth-Genthe C, Gottesman MM. Targeting multidrug resistance in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:219–234. doi: 10.1038/nrd1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart A, Steiner J, Mellows G, Laguda B, Norris D, Bevan P. Phase I trial of XR9576 in healthy volunteers demonstrates modulation of P-glycoprotein in CD56+ lymphocytes after oral and intravenous administration. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4186–4191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Zuylen L, Sparreboom A, van der Gaast A, van der Burg ME, van Beurden V, Bol CJ, Woestenborghs R, Palmer PA, Verweij J. The orally administered P-glycoprotein inhibitor R101933 does not alter the plasma pharmacokinetics of docetaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1365–1371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandler A, Gordon M, De Alwis DP, Pouliquen I, Green L, Marder P, Chaudhary A, Fife K, Battiato L, Sweeney C, Jordan C, Burgess M, Slapak CA. A phase I trial of a potent P-glycoprotein inhibitor, zosuquidar trihydrochloride (LY335979), administered intravenously in combination with doxorubicin in patients with advanced malignancy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3265–3272. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuppens IE, Witteveen EO, Jewell RC, Radema SA, Paul EM, Mangum SG, Beijnen JH, Voest EE, Schellens JH. A phase I, randomized, open-label, parallel-cohort, dose-finding study of elacridar (GF120918) and oral topotecan in cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3276–3285. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chi KN, Chia SK, Dixon R, Newman MJ, Wacher VJ, Sikic B, Gelmon KA. A phase i pharmacokinetic study of the P-glycoprotein inhibitor, ONT-093, in combination with paclitaxel in patients with advanced cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:311–315. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-1439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer M, Zeitlinger M, Karch R, Matzneller P, Stanek J, Jager W, Bohmdorfer M, Wadsak W, Mitterhauser M, Bankstahl JP, Löscher W, Koepp M, Kuntner C, Müller M, Langer O. Pgp-mediated interaction between (R)-[11C]verapamil and tariquidar at the human blood-brain barrier: A comparison with rat data. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:227–233. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreisl WC, Liow JS, Kimura N, Seneca N, Zoghbi SS, Morse CL, Herscovitch P, Pike VW, Innis RB. P-glycoprotein function at the blood-brain barrier in humans can be quantified with the substrate radiotracer 11C-N-desmethyl-loperamide. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:559–566. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.070151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner CC, Bauer M, Karch R, Feurstein T, Kopp S, Chiba P, Kletter K, Löscher W, Müller M, Zeitlinger M, Langer O. A pilot study to assess the efficacy of tariquidar to inhibit P-glycoprotein at the human blood-brain barrier with (R)–11C-verapamil and PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1954, 1961. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.063289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwal S, Hartz AM, Elmquist WF, Bauer B. Breast cancer resistance protein and P-glycoprotein in brain cancer: two gatekeepers team up. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:2793–2802. doi: 10.2174/138161211797440186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potschka H. Role of CNS efflux drug transporters in antiepileptic drug delivery: overcoming CNS efflux drug transport. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:943–952. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choo EF, Kurnik D, Muszkat M, Ohkubo T, Shay SD, Higginbotham JN, Glaeser H, Kim RB, Wood AJ, Wilkinson GR. Differential in vivo sensitivity to inhibition of P-glycoprotein located in lymphocytes, testes, and the blood-brain barrier. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1012–1018. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.099648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauer F, Kuntner C, Bankstahl JP, Wanek T, Bankstahl M, Stanek J, Mairinger S, Dörner B, Löscher W, Müller M, Erker T, Langer O. Synthesis and in vivo evaluation of [11C]tariquidar, a positron emission tomography radiotracer based on a third-generation P-glycoprotein inhibitor. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:5489–5497. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawamura K, Konno F, Yui J, Yamasaki T, Hatori A, Yanamoto K, Wakizaka H, Takei M, Nengaki N, Fukumura T, Zhang MR. Synthesis and evaluation of [(11)C]XR9576 to assess the function of drug efflux transporters using PET. Ann Nucl Med. 2010;24:403–412. doi: 10.1007/s12149-010-0373-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kannan P, Telu S, Shukla S, Ambudkar SV, Pike VW, Halldin C, Gottesman MM, Innis RB, Hall MD. The “specific” P-glycoprotein inhibitor tariquidar is also a substrate and an inhibitor for breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) ACS Chem Neurosci. 2011;2:82–89. doi: 10.1021/cn100078a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sane R, Agarwal S, Elmquist WF. Brain distribution and bioavailability of elacridar after different routes of administration in the mouse. Drug Metabol Dispos. 2012;40:1612–1619. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.045930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawamura K, Yamasaki T, Konno F, Yui J, Hatori A, Yanamoto K, Wakizaka H, Takei M, Kimura Y, Fukumura T, Zhang MR. Evaluation of limiting brain penetration related to P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein using [(11)C]GF120918 by PET in mice. Mol Imaging Biol. 2011;13:152–160. doi: 10.1007/s11307-010-0313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dörner B, Kuntner C, Bankstahl JP, Bankstahl M, Stanek J, Wanek T, Stundner G, Mairinger S, Löscher W, Müller M, Langer O, Erker T. Synthesis and small-animal positron emission tomography evaluation of [11C]-elacridar as a radiotracer to assess the distribution of P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier. J Med Chem. 2009;52:6073, 6082. doi: 10.1021/jm900940f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stokvis E, Rosing H, Causon RC, Schellens JH, Beijnen JH. Quantitative analysis of the P-glycoprotein inhibitor elacridar (GF120918) in human and dog plasma using liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometric detection. J Mass Spectrom. 2004;39:1122–1130. doi: 10.1002/jms.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bates SE, Bakke S, Kang M, Robey RW, Zhai S, Thambi P, Chen CC, Patil S, Smith T, Steinberg SM, Merino M, Goldspiel B, Meadows B, Stein WD, Choyke P, Balis F, Figg WD, Fojo T. A phase I/II study of infusional vinblastine with the P-glycoprotein antagonist valspodar (PSC 833) in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4724–4733. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0829-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fracasso PM, Goldstein LJ, de Alwis DP, Rader JS, Arquette MA, Goodner SA, Wright LP, Fears CL, Gazak RJ, Andre VA, Burgess MF, Slapak CA, Schellens JH. Phase I study of docetaxel in combination with the P-glycoprotein inhibitor, zosuquidar, in resistant malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7220–7228. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]