Abstract

The benefits associated with polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) in tissue engineering include high immunotolerance, low toxicity, and biodegradability. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBHHx), a molecule from the PHA family of biopolymers, shares these features. In this study, the applicability of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), spontaneously differentiated hESCs (SDhESCs), and mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) in conjunction with PHBHHx and collagen as a biocompatible replacement strategy for damaged tissues was exploited. Collagen gel contraction was monitored by seeding cells at controlled densities (0, 103, 104, and 105 cells/mL) and measuring length and diameter at regular time intervals thereafter when cultured in a complete medium. Cell viability was measured by trypan blue exclusion assay. Porous PHBHHx tube scaffolds were prepared using a dipping method followed by salt leaching. PHBHHx/collagen composites were generated via syringe injection of collagen/cell mixtures into sterile PHBHHx porous tubes. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction was used to determine the fate of cells within PHBHHx/collagen scaffolds with tendon, bone, cartilage, and fat-linked transcript expression being explored at days 0, 5 10, and 20. The capacity of PHBHHx/collagen scaffolds to support differentiation was explored using a medium specific for osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineage generation. Collagen gel tube contraction required initial seeding densities of ≥105 hMSCs or SDhESCs in 1.5 mg/mL collagen gel tubes. Gels with a collagen concentration of 3 mg/mL did not display contraction across the examined cell seeding densities. Cell viability was ∼50% for SDhESC and 90% for hMSCs at all cell densities tested in porous PHBHHx tube/3 mg/mL collagen hybrid scaffolds after 20 days in vitro culture. Undifferentiated hESCs did not contract collagen gel tubes and were unviable after 20 days culture. In the absence of additional stimuli, SOX9 was sporadically found, while RUNX2 was not present in both hMSC and SDhESC. Hybrid scaffolds were shown to promote retention of osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic differentiation by expression of RUNX2, SOX9, and PPARγ genes, respectively, following exposure to the appropriate induction medium. PHBHHx/collagen scaffolds have been successfully used to culture hMSC and SDhESC over an extended period supporting the potential of this scaffold combination in future tissue engineering applications.

Introduction

Tissue-engineered scaffolds should mimic the structure and mechanical properties of the tissue they are intended to replace. Many different materials have been investigated as possible tissue engineering scaffolds. These include natural materials, such as collagen1 and silks,2,3 or manufactured materials, such as polymers.4 A current focus for clinical application is on blending these materials to form a hybrid design to both encourage cellular in-growth and provide mechanical support during the remodelling stage of tissue recovery.5,6

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) are a family of biopolymers consisting of polyesters of many different hydroxycarboxylic acid molecules produced by microorganisms as energy and carbon storages in response to unbalanced culture conditions.7 Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBHHx) is the designation of molecules consisting of random copolymers of 3-hydroxybutyrate and 3-hydroxyhexanoate and is one of the few PHA molecules that can currently be produced on a sufficient scale for use in both scientific research and medical device construction.8,9 PHBHHx has great potential as a material for tissue engineering owing to its adaptable mechanical properties, biodegradability, and apparent compatibility with many different mesenchymal cell types, including rabbit mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived bone,10 human adipose-derived stem cells, human keratinocytes,11 mouse fibroblasts,12 and rat peripheral nerve,13 rat tenocytes, and human MSCs (hMSCs).14

Collagen, a major structural molecule, represents a major component of many different extracellular matrices (ECMs). Tissue collagen composition varies according to function. Articular cartilage matrix can contain 75% and 80% type II collagen depending on its position in the joint, allowing it to resist the high compression forces found in areas such as joints and intervertebral disks.15 Tendon and ligament matrices can contain ∼90% type I collagen arranged in hierarchical fibrils to accommodate high tensional forces.16 Several collagen types (I, III, IV) fluctuate with increased skeletal muscle activity, where prolonged intense exercise can increase the abundance of type IV collagen,17 whereas bone contains high amounts of collagens I and III allowing flexibility during movement.18 Due to its abundance and prevalence, collagen is viewed as an appropriate scaffold material, especially in orthopedic tissue engineering due to the wide-scope of potential applications and complementary clinical trial data.19

Adult tissues are comprised of multiple cell types; however, dominant cell types are found within individual tissues. Tenocytes account for over 90% of the cellular mass of a tendon and are responsible for maintaining the collagen-based ECM that forms the tendon structure.20 Cartilage has a similar percentage of chondrocytes that are again responsible for ECM maintenance.21 Bone has two main cell types responsible for maintaining ECM: osteoclasts, which secrete molecules to break down calcified tissue, and osteoblasts, which are responsible for rebuilding it.22 Skeletal muscle cells differ from previous examples in that they play a larger role in tissue contractile function rather than ECM production.23 However, fully differentiated cells can be unsuitable for tissue engineering applications due to their limited proliferation capacity when cultured in vitro, so exploration of other less differentiated cells has become widespread.24–26

MSCs are a useful cell source for tissue engineering as they can be easily sourced, isolated, and cultured in vitro.27 Exposure of MSCs to tensile forces and/or growth factor supplementation is described as producing cells that resemble connective tissue cells in expression marker profile and physiological activity.23,28–30 Pluripotent human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), derived from the inner cell mass of preimplantation blastocysts, are also strong candidates for tissue engineering application.31 They are the precursor to almost all adult tissues in the body, including the mesenchyme layer of cells, and thus tendon-,32 cartilage,-33,34 and bone-like cells26 have all been derived during in vitro and in vivo differentiation. hESCs are relatively readily available and could potentially be used to produce an allogeneic off-the-shelf cellular product following on from current safety trials underway in the UK and the USA.

Here we sought to determine the suitability of PHBHHx and collagen hybrid constructs for use with hESC, spontaneously differentiated hESC (SDhESC), and hMSC with a view to creating a tissue-engineered product. We determined that PHBHHx/collagen hybrid scaffolds are appropriate for tissue engineering applications, demonstrating that both adult hMSC and SDhESC viability remained high after prolonged in vitro culture, with an overall lack of stimulus-independent differentiation.

Materials and Methods

PHBHHx scaffold preparation and characterization

2 g PHBHHx powder (87.9% HB, 12.1% HHx) (Lukang Group) was dissolved in 20 mL chloroform (Beijing Chemical Works, 20100303) in a 50 mL conical flask. Once dissolved, 0.04 g (<100 μm diameter) NaCl crystals (Sigma Aldrich) were suspended in the solution and homogenized by shaking/stirring. Tube construction was performed using a 2.5-mm-diameter stainless steel mandrill that was dipped into the homogenized PHBHHx/NaCl solution for 1 s, removed, and solvent-evaporated in a flow hood for 2 min. This process was repeated five times, after which the mandrill was fixed vertically for 60 min to allow the solvent to fully evaporate and the polymer to become rigid. The polymer tube was carefully removed by hand and immersed in deionized H2O overnight to introduce porosity through NaCl crystal dissolution. Before experimental use scaffolds were cleaned with immersion in 70% industrial methylated spirits followed by UV light exposure for 24 h. Immediately before use, scaffolds were immersed in a cell-specific medium for 1 h. Scanning electron microscopy (FEI Quanta 200, Tsinghua Medical School, Beijing) was performed to explore topographical structures. ImageJ software (NIH) analysis was used to quantify both size and density of pores. Random 1-mm2 regions were taken and a grid overlaid to allow for easier counting. The line draw tool was utilized to measure pore diameter, with the appropriate scaling factor applied. All pores in 1-mm2 regions were counted and measured.

Collagen scaffolds

Collagen gels were formed by first neutralizing type I rat tail collagen (Sigma Aldrich, C3867-1VL) with 1 M NaOH, and combining with 10×Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) at a ratio of nine parts collagen solution to one part 10×DMEM, while maintaining a low temperature throughout by placing samples in an ice bath. Cells were added via their prior suspension in the one part 10×DMEM. Gels were injected into the casting apparatus and were then cross-linked via temperature elevation to 37°C for 2 h (Fig. 1). Gels were formulated to either 1.5 mg/mL or 3 mg/mL final collagen concentrations.

FIG. 1.

Collagen gel molding procedure. Collagen gel was injected into the modified end of a 1 mL plastic sterile syringe, and then the plunger from a second syringe inserted to close the open end. After 2 h of incubation, one plunger was removed and the other plunger depressed to eject the collagen tube. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

PHBHHx/collagen hybrid scaffolds

PHBHHx/collagen scaffolds were created by injecting 1.5 mg/mL or 3 mg/mL collagen gel (as described previously) seeded with hESC, SDhESC, or hMSC at a 1×104 cells/mL concentration into the lumen of the PHBHHx tube before incubation at 37°C for 2 h. After incubation, constructs were transferred to six-well plates and immersed in a 3-mL cell-specific complete medium (as described below). Measurements of tube length and diameter were taken at days 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20.

Cell culture

Human mesenchymal stem cell

Cells were isolated from human bone marrow using adherence culture as described previously.35 Once isolated, cells were cultured on 10 ng/mL fibronectin (Sigma Aldrich)-coated flasks in the hMSC medium (DMEM, 5% fetal bovine serum [FBS], non-essential amino acids [NEAA], and l-glutamine [l-glut]) in a 2% O2 incubator, with the medium changed twice weekly. Cells were split at 90% confluency during expansion via trypsin/EDTA dissociation before centrifugation at 1200 rpm for 3 min. Cell pellets were then re-suspended in 1 mL complete medium, and passaged according to 1:2 split ratios.

Human embryonic stem cell

SHEF1 were cultured in feeder free conditions according to previously published methodology.36 Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) were first cultured to 50% confluency in a standard medium (DMEM, 10% FBS, 1% NEAA, and 1% l-glut) after which the medium was changed to the hESC medium (KO DMEM [Invitrogen], 20% serum replacement [Invitrogen], 1% l-glut, 1% NEAA, 10 mM β-mecaptoethanol [Invitrogen], and 4 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor [bFGF; Lonza]). After 24 h, the conditioned medium was collected, filtered, and further supplemented with an additional 4 ng/mL bFGF. The conditioned hESC medium was used to culture hESCs on Matrigel (BD Biosciences)-coated flasks. During expansion, the hESC medium was changed daily and cells were split 1:2 at 90% confluency with fresh trypsin/EDTA dissociation for <1 min. Centrifugation and passage regimes are as described for hMSC.

Spontaneous differentiation of hESC

hESC (SHEF1) were seeded into Matrigel-coated T-75 flasks at fixed densities (1×106 per flask) in the conditioned hESC medium. Spontaneous differentiation was induced by changing the base medium to a standard MEF medium for 5 days, changing the medium after 3 days.

Cell viability

Cell viability was determined with the Trypan Blue dye exclusion assay (Sigma Aldrich) according to manufacturer's instructions. To isolate collagen-embedded cells, gels were first immersed in 1 mL 0.4% Collagenase Type IV (Sigma Aldrich)/DMEM solution for 2 h at 37°C followed by centrifugation at 1200 rpm for 3 min. Cell counting was performed using a hemocytometer.

Molecular characterization

RNA lysates were obtained by first suspending gel-isolated cells in lysis buffer (RNeasy; Qiagen) followed by QIAshredder spin column (Qiagen)-based homogenization. Samples were stored at −80°C before final extraction. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer's protocols. The amount of RNA present in the final sample solution was quantified using a Thermo Scientific Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer. Samples were stored at −80°C until analysis could be undertaken. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed using the Invitrogen Superscript kit following the manufacturer's protocol, with an RNA input of 1 μL of a 5 ng/μL stock solution, with forward and reverse primers for SOX9 (cartilage), RUNX2 (bone), PPARγ (fat), and B-Actin (housekeeping gene) for 40 cycles on a SansoQuest labcycler (Geneflow) (see Table 1 for further details). PCR products were detected via electrophoresis on 2% agarose/1×tris base acetic acid/EDTA (TAE) (Sigma Aldrich) with 10 mg/mL ethidium bromide (Sigma Aldrich) for subsequent UV-based detection, with gels immersed in 1×TAE buffer. Electrophoresis was performed for 60 min at 100 V using a BioRad Power PAC 3000 and imaged using a Syngene Gel UV illuminator and GeneSnap imaging software.

Table 1.

RT-PCR Primer Sequence, Annealing Temperatures, and Product Size

| Name | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) | Sequence length (bp) | Temperature (°C) | Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOX-9 | TCATGAAGATGACCGACG | CTGGTACTTGTAATCCGG | 506 | 54 | 40 |

| RUNX2 | CCCCACGACAACCGCACCAT | CACTCCGGCCCACAAATCTC | 289 | 48 | 40 |

| PPARγ | CTTTTGCTGAGCTTCTTTCA | TGAAAGAAGCTCAGAAAGC | 203 | 55 | 40 |

| B-Actin | GCCACGGCTGCTTCCAGC | AGGGTGTAACGCAACTAAGTC | 504 | 55 | 40 |

Genes examined were SOX-9 (cartilage), RUNX2 (bone), PPARγ (adipose), and B-Actin (housekeeping gene).

RT-PCR, reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction.

Induced differentiation

Cells were suspended in constructs and cultured in static culture for a maximum of 20 days, with sampling at days 0, 5, 10, and 20. A control of the standard MSC medium was run concurrently. At each time point, gels were removed from tubes, immersed in 0.4% type IV collagenase for 1 h at 37°C, pelleted, and resuspended in lysis buffer, and RNA was extracted and molecular characterization was performed. Osteogenic differentiation was induced by culturing in the osteogenic differentiation medium (DMEM, 10% FBS, l-glut, NEAA, 0.1 μM dexamethasone, and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate; Sigma Aldrich). Chondrogenesis was induced by culturing in the chondrogenic medium (DMEM, 10% FBS, l-glut, NEAA, 0.1 μM dexamethasone, and 50 μM ascorbic acid; Sigma Aldrich), 40 μg/mL l-Proline (Sigma Aldrich), and 10 ng/mL transforming growth factor (TGF)-β3 (Peprotech). Adipogenesis was induced by culturing in the adipogenic medium (DMEM, 10% FBS, l-glut, NEAA, 0.5 μM dexamethasone, and 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine; Sigma Aldrich), 10 μg/mL insulin (Sigma Aldrich), and 100 μM indomethacin (Sigma Aldrich).

Results

Collagen gel contraction

We first sought to determine the maximal cell seeding density of hESC, hMSC, and SDhESC into collagen gel tubes at which contraction would not occur and cell viability was maintained. hESCs did not contract collagen gels at any collagen concentration or cell density combination explored over 20 days (Fig. 2 A, D, G, J).

FIG. 2.

Collagen gel contraction is dependent on both collagen concentration and cell concentration. (A, D) 1.5-mg/mL gels do not contract when seeded with human embryonic stem cells (hESCs). (B, E) Significant contraction in both length and diameter seen after 10 days of culture in 1.5-mg/mL gels seed with 1×105 spontaneously differentiated hESCs (SDhESCs)/mL. (C, F) Significant contraction in both length and diameter seen after 10 days of culture in 1.5-mg/mL gels seeded with 1×105 human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs)/mL. (G, J) 3-mg/mL gels do not contract when seeded with hESCs. (H, K) 3-mg/mL gels do not contract when seeded with SDhESCs. (I, L) 3-mg/mL gels do not contract when seeded with hMSCs. Graphs show mean±1SD, n=3. *indicates p≤0.05 vs. acellular controls.

Unlike the parental hESC, SDhESCs with an initial cell seeding density of 1×105 cells/mL contracted 1.5 mg/mL collagen gel length and diameter after 10 days (1.63±0.15 cm vs. 2.43±0.06 cm, p=0.02) (Fig. 2 B). Contraction continued progressively at days 15 (1.46±0.25 cm vs. 2.24±0.06 cm, p=0.04) and 20 (0.87±0.31 cm vs. 2.37±0.15 cm, p=0.02). The gel diameter contracted across these time points (p≤0.03) (Fig. 2 E). SDhESC did not contract the 3-mg/mL gel length or diameter irrespective of the initial cell seeding density (Fig. 2 H, K).

hMSCs contracted both the length (1.26±0.07 cm vs. 2.93±0.05 cm, p=0.002) and diameters (0.23±0.03 cm vs. 0.46±0.06 cm, p=0.035) of 1.5 mg/mL collagen gels after 10 days with an initial seeding density of 1×105 cells/mL (Fig. 2C, F). Continued contraction was also apparent for both gel length and diameter at days 15 (p=0.02) and 20 (p=0.002). The gel diameter also significantly reduced at these time points (p≤0.02). Where initial cell seeding densities of ≤1×104 cells/mL were used, no significant collagen gel contraction was observed (Fig. 2C, F). hMSCs did not contract 3 mg/mL collagen gels (Fig. 2 I, L).

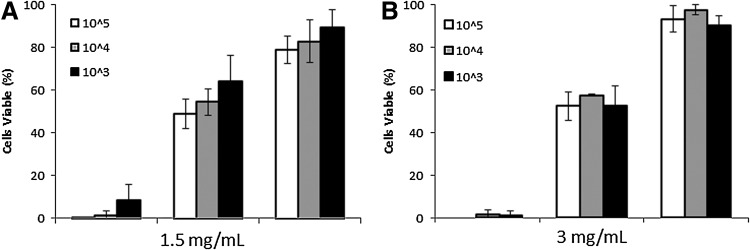

Cell viability in collagen gels

Subsequent analysis of hESC cell viability at day 20 demonstrated that with 1.5 mg/mL gels ≤8.4%±7.5% of cells remained viable (Fig. 3A) and in 3 mg/mL gels ≤1.4%±2.4% viable (Fig. 3B). SDhESC viability after 20 days was determined as ≥48.6%±6.8% in 1.5 mg/mL gels (Fig. 4 A) and ≥52.3%±6.6% in 3 mg/mL gels (Fig. 5 B) for all cell densities. hMSC viability after a 20-day incubation period within collagen gels was ≥78%±6.3% in 1.5 mg/mL (Fig. 5 A) and ≥89%±8.5% in 3 mg/mL (Fig. 4 B) gels at all cell densities tested.

FIG. 3.

hMSC and SDhESC retain high viability levels after 20 days collagen gel suspension. Percentage of trypan blue-negative cells found as a total of all cells. (A) Cells seeded in 1.5 mg/mL collagen gels. (B) Cells seeded in 3 mg/mL collagen gels. Graph shows mean±1 standard deviation, n=3.

FIG. 4.

Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBHHx) tube pore size determination. (A) PHBHHx tube structure at 50×magnification. (B) Representative tube section at 200×with line measurement indicators showing pore diameter. (C) Pore diameter histogram. Measurements were taken from random 1-mm2 regions of polymer tube (n=5). Error bars indicate one standard deviation.

FIG. 5.

hMSC and SDhESC retain viability after 20 days in a PHBHHx/collagen gel hybrid scaffold. An initial seeding density of 1×104 cells/mL was evaluated for viability with Trypan Blue staining after 20 days. Percentage of viable (trypan blue negative) cells shown (n=5). Error bars indicate one standard deviation.

PHBHHx tube pore characterization

PHBHHx tubes were manufactured to contain salt crystals that could be leached out to generate pores distributed across the tube structure. Analysis determined that pores had an average diameter of 0.025±0.019 mm (n=330) at a density of 68.6±10.55 pores/mm2 (n=5) (Fig. 4). The majority of pores had a diameter of ≤0.04 mm [89.1% (294/330)], while 33.0% had diameters in the range of 0.02–0.03 mm, and. 1.5% (5/330) of pores had diameters ≥0.1 mm.

Viability in PHBHHx/collagen hybrid scaffolds

PHBHHx/collagen/cell scaffolds were immersed in a culture medium and maintained over a 20-day period before cell removal by enzymatic digestion. hMSCs retained high viability, 87.7%±4.6% after 20 days of culture (Fig. 5). SDhESCs displayed lower viability, 46.2%±16.1% viable after 20 days of culture when compared to hMSC. These values are broadly similar to those obtained following on from incubation in collagen gels alone, indicating that the PHBHHx scaffold had little impact on cell viability.

Molecular characterization

We finally sought to determine if the PHBHHx/collagen hybrid scaffold played a role in directing spontaneous differentiation of hMSC or SDhESC into select musculoskeletal lineages. Induced differentiation was achieved by culturing cells/constructs in an adipogenic, chondrogenic, or osteogenic medium. SOX-9 expression was maintained until day 10 but lost thereafter in hMSCs, whereas chondrogenic medium culture resulted in positive expression at day 20. RUNX2 expression was rapidly lost in hMSC in standard conditions. Osteogenic medium culture resulted in RUNX2 expression after 10 days, whereas PPARγ expression was not evident in hMSCs unless cultured in adipogenic medium (Fig. 6A). SDhESC SOX-9 expression was again maintained until day 10 but lost thereafter, while RUNX2 expression was not detected at any time point (Fig. 6B). β-Actin was included as a loading control. We were unable to detect expression of tenomodulin in experimental samples, indicating the absence of differentiation into the tendon lineage (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

hMSC and SDhESC did not undergo spontaneous differentiation after 20 days of PHBHHx/collagen gel scaffold encapsulation (A). Induced differentiation of hMSCs led to restoration of chondrogenic expression, adoption of osteogenic expression, and maintained adipogenic expression. Differentiation medium hMSC β-actin (BACT) representative of all three medium conditions (B). Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction-based evaluation of BACT, SOX9, PPARγ and RUNX2 expression levels after 0, 5, 10, or 20 days in construct. Undifferentiated hESC are included as control for SDhESC.

Discussion

Tissue engineering or regenerative medicine aims to use scaffolds and cells to regenerate and restore function of tissue lost through damage, disease, and disorder. The use of PHBHHx has been explored by many labs investigating multiple potential applications, including cellular interactions and its use as a scaffold in tissue engineering.4,10–14 Here we demonstrated the interaction of human embryonic and MSCs with collagen gels and PHBHHx/collagen hybrid scaffolds using a range of static in vitro experimentation to assess suitability for further tissue engineering applications. We show that hMSCs and SDhESCs can be cultured for extended periods on PHBHHx/collagen hybrid scaffolds and thereby confirm its suitability as a model system.

The application and suitability of PHBHHx as a scaffold material in orthopedic models and for human and animal stem cell biocompatibility has been described elsewhere.14,36,38 For instance, rat MSCs adhered to and elongated along the length of electrospun PHBHHx scaffolds where fiber orientation played a strong role in promotion of differentiation: aligned promoted osteogenesis, whereas random promoted adipogenesis.37 Cartilage-like structures have also been formed by human adipose-derived stem cells pre-seeded onto salt leached, porous 3D PHBHHx foams, then successfully implanted subcutaneously into a nude mouse model.38 These and our studies demonstrate that PHBHHx is a suitable material for stem cell-based tissue engineering, with the capacity to support MSC differentiation into multiple musculoskeletal lineages.

Type I collagen gels supported the differentiation of murine ESCs into either osteogenic or chondrogenic lineages when seeded into 2D and 3D 1.2 mg/mL scaffolds. The additional presence of linage-specific supplements (beta-glycerol phosphate—bone, chondroitin sulphate—cartilage) was found to further increase differentiation above that found in control collagen gels, with greater expression of SOX-9 (55-fold vs. 7.5-fold increase) and osteocalcin (30-fold vs. 15-fold increase) measured using qRT-PCR after 15 days of culture. Viability within the collagen gels was unclear, but surface viability was approximately 60% after 15 days of culture.39 Human and murine ESC culture in 0.75 mg/mL type I collagen gels has also been achieved by pre-differentiating cells into embryoid bodies before suspension. After 21 days of collagen gel suspension, cells exhibited a spindle-like morphology and demonstrated contractile behavior in the presence of TGF-β.40 Undifferentiated ESCs were not compatible with our PHBHHx/collagen gel hybrid scaffold system. Our study has demonstrated that hESCs required a prior spontaneous differentiation step induced by exposure to fetal bovine serum before collagen gel suspension to shift cell phenotype away from that of a self-renewing ESC into a partially differentiated heterogeneous population. Here we report viability and contractile behavior of hESC and predifferentiated hESC in PHBHHx/collagen gel hybrid scaffolds after a predifferentiation stage, and demonstrate a 40%–60% cell viability of SDhESC after 20 days of continuous static culture.

Differentiation of MSCs in hydrogel-based scaffolds has been well researched. Bone marrow-derived MSCs and umbilical cord-derived MSCs were compared in a study investigating differentiation in collagen I/III gels, finding that in the absence of a lineage-specific medium neither osteogenesis or adipogenesis was stimulated; however, osteogenesis was induced in both cell types after 21 days.41 Mechanostimulation has been suggested as an alternative to chemostimuli when inducing MSC differentiation on collagen scaffolds. A cyclic compressive strain study on hMSC-seeded collagen-alginate gels demonstrated upregulation of RUNX2 after 7 days when compared to static unloaded controls.42 This suggests that cells were becoming more osteoblastic, as the RUNX2 transcription factor has been shown to be critical for the promotion of osteogenic differentiation.43 By inducing chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs in collagen I gels, it was found that increased chondrogenesis could be achieved by increasing both collagen concentration in the gel and the initial cell seeding density. However, similar to our study, they found that chondrogenesis was induced in 3 mg/mL collagen gels seeded with 1×105 MSCs after 21 days of static culture.44 β Actin is frequently used as a housekeeping gene due to its consistent presence as a cytoskeletal component of mammalian cells, and is commonly used as a marker of cellular viability.45 We noted expression of β Actin at all-time points, which when coupled to the high cell viability provides an additional demonstration of viable cell transcriptional activity. Expression of lineage-specific molecular markers for multiple tissue lineages suggested that cells were maintaining a stem cell-like phenotype over 20 days of static culture in PHBHHx/collagen hybrid scaffolds.

Collagen gel contraction by fibroblastic cells is well established.46 Cells interact with the surrounding ECM via strong inward tractions located at the tips of long slender extensions, similar to those used for surface migration.47 Platelet-derived growth factor, a molecule released by cells in damaged tissue,48 is one of the many stimuli considered to be responsible for causing the extensions to contract.49 Investigations into the effects of matrix composition and cell density found that by decreasing collagen gel concentrations from 2.6 to 1.3 mg/mL, a greater impact on gel contraction kinetics was achieved when compared to the effects of increasing the rabbit MSC density by the same fold increase (500 K to 1 M cells/mL).50 This suggests that the availability of fibril binding sites in the collagen is the rate-limiting factor in contraction rather than seeding density per se. Similarly, human corneal fibroblasts can contract a 4.5 mg/mL collagen gel over a 25-day static culture period when seeded at a cell concentration of 5×105 cells/mL, but not 1×105 cells/mL.51 These reports correlate with our observations where little contraction was observed in the 3 mg/mL groups, and the rate of contraction slowed with 1.5 mg/mL gels seeded with lower cell densities. We have successfully identified a cell:collagen ratio with negligible collagen contraction and high cell viability in the absence of additional stimuli for application in studies utilizing either hMSC or SDhESC. Minimal collagen contraction is an essential feature of this tissue-engineered product, promoting further integration into host tissue when placed in vivo, increasing the likeliness of cellular infiltration and overall rate of recovery.52

Herein we have demonstrated that undifferentiated hESCs are not viable after 20 days of culture within a PHBHHx/collagen gel hybrid scaffold, whereas hMSCs and SDhESCs demonstrated good viability over the long-term. Gel contraction was negligible with collagen concentrations of 3 mg/mL with all cell types at all investigated seeding densities. We were unable to detect any evidence of spontaneous differentiation into fat, bone, cartilage, or tendon lineages in static culture but describe a scaffold capable of supporting differentiation when provided with the correct medium supplementation. In summary, we have developed a porous PHBHHx/collagen gel hybrid scaffold that features good cell compatibility and an absence of spontaneous lineage-forming differentiation cues. This scaffold system is readily translatable into dynamic systems and differentiation models across multiple lineages.

Acknowledgments

We thank the DTC Regenerative Medicine EP/F/500491/1, Keele University Acorn Funding, MRC Doctoral Training Fund G0800103, and EU Seventh Framework PIRSES-GA-2008-230791 for funding this research.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Chen X. Qi Y. Wang L.L. Yin Z. Yin G.L. Zou X.H. Ouyang H.W. Mechanoactive tenogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells ligament regeneration using a knitted silk scaffold combined with collagen matrix. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3683. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan H. Liu H. Toh S.L. Goh J.C. Anterior cruciate ligament regeneration using mesenchymal stem cells and silk scaffold in large animal model. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4967. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang Q. Chen D. Yang Z. Li M. In vitro and in vivo research on using Antheraea pernyi silk fibroin as tissue engineering tendon scaffolds. Mat Sci Eng C. 2009;29:1527. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen G.Q. The application of polyhydroxyalkanoates as tissue engineering materials. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6565. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longo U.G. Lamberti A. Maffulli N. Denaro V. Tendon augmentation grafts: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2010;94:165. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldp051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoeferlin A. Hoehel K.D. Estimation of the inflammatory reaction by CRP-levels following prosthetic hernia repair. Hernia. 2000;4:248. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiu Y.Z. Han J.J. Chen G.Q. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from gluconate and glucose by recombinant Aeromonas hydrophila and Pseudomonas putida. Biotechnol Lett. 2005;27:1381. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-3685-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen G.Q. Zhang G. Park S.J. Lee S.Y. Industrial scale production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;2001:50. doi: 10.1007/s002530100755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen G.Q. A microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) based bio- and materials industry. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:2434. doi: 10.1039/b812677c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y.W. Wu Q. Chen G.Q. Attachment, proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts on random biopolyester poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3- hydroxyhexanoate) scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2004;25:669. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00561-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji Y. Li X.T. Chen G.Q. Interactions between a poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) terpolyester and human keratinocytes. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3807. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y.W. Wu Q. Chen G.Q. Reduced mouse fibroblast cell growth by increased hydrophilicity of microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates via hyaluronan coating. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4621. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bian Y.Z. Wang Y. Aibaidoula G. Chen G.Q. Wu Q. Evaluation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. Biomaterials. 2009;30:217. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lomas A.J. Chen G.Q. El Haj A.J. Forsyth N.R. Poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) supports adhesion and migration of mesenchymal stem cells and tenocytes. World J Stem Cells. 2012;4:94. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v4.i9.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung C. Burdick J.A. Engineering cartilage tissue. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:243. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doral M.N. Alam M. Bozkurt M. Turhan E. Atay O.A. Dönmez G. Maffulli N. Functional anatomy of the Achilles tendon. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:638. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackey A.L. Donnelly A.E. Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T. Roper H.P. Skeletal muscle collagen content in humans after high-force eccentric contractions. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:197. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01174.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider R.K. Puellen A. Kramann R. Raupach K. Bornemann J. Knuechel R. Pérez-Bouza A. Neuss S. The osteogenic differentiation of adult bone marrow and perinatal umbilicalmesenchymal stem cells and matrix remodelling in three-dimensionalcollagen scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2010;31:467. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunniffe G.M. O'Brien F.J. Collagen scaffolds for orthopedic regenerative medicine. J Miner Met Mat. 2011;63:4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulze-Tanzil G. Mobasheri A. Clegg P.D. Sendzik J. John T. Shakibaei M. Cultivation of human tenocytes in high-density culture. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122:219. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0694-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwasa J. Ochi M. Uchio Y. Katsube K. Adachi N. Kawasaki K. Effects of cell density on proliferation and matrix synthesis of chondrocytes embedded in atelocollagen gel. Artif Organs. 2003;27:249. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2003.07073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clover J. Dodds R.A. Gowen M. Integrin subunit expression by human osteoblasts and osteoclasts in situand in culture. J Cell Sci. 1992;103:267. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.1.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krampera M. Pizzolo G. Aprili G. Franchini M. Mesenchymal stem cells for bone, cartilage, tendon and skeletal muscle repair. Bone. 2006;39:678. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seong J.M. Kim B.C. Park J.H. Kwon I.L. Mantalaris A. Hwang Y.S. Stem cells in bone tissue engineering. Biomed Mater. 2010;5 doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/5/6/062001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jukes J.M. Moroni L. Van Blitterswijk C.A. De Boer J. Critical steps toward a tissue-engineered cartilage implant using embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng A. 2008;14:135. doi: 10.1089/ten.a.2006.0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jukes J.M. Both S.K. Leusink A. Sterk L.M. van Blitterswijk C.A. de Boer J. Endochondral bone tissue engineering using embryonic stem cells. PNAS. 2008;105:6840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711662105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuan R.S. Boland G. Tuli R. Adult mesenchymal stem cells and cell-based tissue engineering. Arthritis Res Ther. 2002;5:32. doi: 10.1186/ar614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Violini S. Ramelli P. Pisani L.F. Gorni C. Mariani P. Horse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells express embryo stem cell markers and show the ability for tenogenic differentiation by in vitro exposure to BMP-12. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q.W. Chen J.L. Piao J.Y. Mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into tenocytes by Bone Morphogenic Protien (BMP) 12 gene transfer. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005;100:418. doi: 10.1263/jbb.100.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bullough R. Finnigan T. Kay A. Maffulli N. Forsyth N.R. Tendon repair through stem cell intervention: cellular and molecular approaches. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:1746. doi: 10.1080/09638280701788258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomson J.A. Itskovitz-Eldor J. Shapiro S.S. Waknitz M.A. Swiergiel J.J. Marshall V.S. Jones J.M. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vallier L. Touboul T. Chung Z. Brimpari M. Hannan N. Millan E. Smithers L.E. Trotter M. Rugg-Gunn P. Weber A. Roger A. Pedersen R.A. Early cell fate decisions of human embryonic stem cells and mouse epiblast stem cells are controlled by the same signalling pathways. PLoS One. 2009;4:1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vats A. Bielby R.C. Tolley N. Dickinson S.C. Boccaccini A.R. Hollander A.P. Bishop A.E. Polak J.M. Chondrogenic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells: the effect of the micro-environment. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1687. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forsyth N.R. McWhir J. Human embryonic stem cell telomere length impacts directly on clonal progenitor isolation frequency. Rejuv Res. 2008;11:5. doi: 10.1089/rej.2007.0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wimpenny I. Hampson K. Yang Y. Ashammakhi N. Forsyth N.R. One-step recovery of marrow stromal cells on nanofibers. Tissue Eng C. 2010;16:503. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu C. Inokuma M.S. Denham J. Golds K. Kundu P. Gold J.D. Carpenter M.K. Feeder-free growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotech. 2001;19:971. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y. Gao R. Wang P.P. Jian J. Jiang X.L. Yan C. Lin X. Wu L. Chen G.Q. Wu Q. The differential effects of aligned electrospun PHBHHx fibers on adipogenic and osteogenic potential of MSCs through the regulation of PPAR gamma signaling. Biomaterials. 2012;33:485. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ye C. Hu P. Ma M.X. Xiang Y. Liu R.G. Shang X.W. PHB/PHBHHx scaffolds and human adipose-derived stem cells for cartilage tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4401. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krawetz R.J. Taiani J.T. Wu Y.E. Liu S. Meng G. Matyas J.R. Rancourt D.E. Collagen I scaffolds cross-linked with beta-glycerol phosphate induce osteogenic differentiation of embryonic stem cells in vitro and regulate their tumorigenic potential in vivo. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:1014. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Togo S. Sato T. Sugiura H. Wang X. Basma H. Nelson A. Liu X. Bargar T.W. Sharp J.G. Rennard S.I. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells into fibroblast-like cells in three-dimensional type I collagen gel cultures. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 2011;47:114. doi: 10.1007/s11626-010-9367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schneider P.R. Buhrmann C. Mobasheri A. Matis U. Shakibaei M. Three-dimensional high-density co-culture with primary tenocytes induces tenogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1351. doi: 10.1002/jor.21400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spencer V.A. Costes S. Inman J.L. Xu R. Chen J. Hendzel M.J. Bissell M.J. Depletion of nuclear actin is a key mediator of quiescence in epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:123. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang C.Y. Reuben P.M. Cheung H.S. Temporal expression patterns and corresponding protein inductions of early responsive genes in rabbit bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells under cyclic compressive loading. Stem cells. 2005;23:1113. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hui T.Y. Cheung K.M.C. Cheung W.L. Chan D. Chan B.P. In vitro chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in collagen microspheres: influence of cell seeding density and collagen concentration. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3201. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lefebvre V. de Crombrugghe B. Toward understanding SOX9 function in chondrocyte differentiation. Matrix Biol. 1998;16:529. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dallon J.E. Ehrlich H.P. A review of fibroblast-populated collagen lattices. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:474. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Legant W.R. Miller J.S. Blakely B.L. Cohen D.M. Genin G.M. Chen C.S. Measurement of mechanical tractions exerted by cells within three-dimensional matrices. Nat Methods. 2010;7:969. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grinnell F. Fibroblast–collagen matrix contraction: growth-factor signalling and mechanical loading. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;10:362. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01802-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knapp D.M. Tower T.T. Tranquillo R.T. Barocas V.H. Estimation of cell traction and migration in an isometric cell traction assay. AICHE J. 1999;45:2628. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nirmalanandhan V.S. Levy M.S. Huth A.J. Butler D.L. Effects of cell seeding density and collagen concentration on contraction kinetics of mesenchymal stem cell–seeded collagen constructs. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1865. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahearne M. Wilson S.L. Liu K.K. Rauz S. El Haj A.J. Yang Y. Influence of cell and collagen concentration on the cell matrix mechanical relationship in a corneal stroma wound healing model. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:584. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beason D.P. Connizzo B.K. Dourte L.M. Mauck R.L. Soslowsky L.J. Steinberg D.R. Bernstein J. Fiber-aligned polymer scaffolds for rotator cuff repair in a rat model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:245. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]